Abstract

Background

We recently reported that exposure of human cells in vitro to acetaldehyde resulted in activation of the Fanconi anemia-breast cancer associated (FA-BRCA) DNA damage response network.

Methods

To determine whether intracellular generation of acetaldehyde from ethanol metabolism can cause DNA damage and activate the FA-BRCA network, we engineered HeLa cells to metabolize alcohol by expression of human alcohol dehydrogenase 1B.

Results

Incubation of HeLa-ADH1B cells with ethanol (20 mM) resulted in acetaldehyde accumulation in the media which was prevented by co-incubation with 4-methyl pyrazole (4-MP), a specific inhibitor of ADH. Ethanol treatment of HeLa-ADH1B cells produced a 4-fold increase in the acetaldehyde-DNA adduct, N2-ethylidene-dGuo, and also resulted in activation of the Fanconi anemia -breast cancer susceptibility (FA-BRCA) DNA damage response network, as indicated by a monoubiquitination of FANCD2, and phosphorylation of BRCA1. Ser 1524 was identified as one site of BRCA1 phosphorylation. The increased levels of DNA adducts, FANCD2 monoubiquitination, and BRCA1 phosphorylation were all blocked by 4-MP, indicating that acetaldehyde, rather than ethanol itself, was responsible for all three responses. Importantly, the ethanol concentration we used is within the range that can be attained in the human body during social drinking.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that intracellular metabolism of ethanol to acetaldehyde results in DNA damage which activates the FA-BRCA DNA damage response network.

Introduction

Alcohol (ethanol) is carcinogenic to humans in the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT), liver, colorectum, and the female breast (Baan et al., 2007). There is convincing evidence that acetaldehyde, the primary metabolite of ethanol, plays a major role in alcohol-related esophageal cancer (Secretan et al., 2009). With regard to other targets for alcohol - related cancer, several possible mechanisms have been proposed, including changes in ovarian hormone levels, alterations in DNA methylation, and acetaldehyde formation (Dumitrescu and Shields, 2005, Seitz and Stickel, 2007).

The Fanconi anemia-breast cancer susceptibility (FA-BRCA) DNA damage response network (Wang, 2007, Moldovan and D’Andrea, 2009). comprises two interacting components. The Fanconi component appears to be particularly important for the repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks, whereas the BRCA component responds to stalled replication forks, and is important for homologous recombination (Shen et al., 2009). We recently showed that exposure of human cells to acetaldehyde resulted in activation of the FA-BRCA network as indicated by increased FANCD2 monoubiquitination and phosphorylation of BRCA1 (Marietta et al., 2009). Consistent with a DNA damage response, acetaldehyde generates several different types of DNA adducts that can block DNA replication (Brooks and Theruvathu, 2005). Elevated levels of acetaldehyde-DNA adducts have been observed in human alcoholics with ALDH2 (aldehyde dehydrogenase 2)-deficiency (Matsuda et al., 2006), and in the liver (Matsuda et al., 2007) and stomach (Nagayoshi et al., 2009) of Aldh2−/− mice exposed to 20% ethanol in drinking water for 5 weeks.

Exposure of cells to exogenous acetaldehyde is a reasonable in vitro model system for studying alcohol-related UADT and colon cancer, since high levels of extracellular acetaldehyde can be generated in the saliva and colon from alcohol metabolism by microorganisms (bacteria and yeast) (Salaspuro, 2009). However, for breast or liver cancer, the relevant issue is whether chronic low level elevation of acetaldehyde resulting from intracellular ethanol metabolism by alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH) can cause DNA damage. Recombinant human cell lines expressing alcohol metabolizing enzymes have proven useful for many experimental questions (Donohue et al., 2001). Therefore in the present work we engineered HeLa cells, which are particularly useful for monitoring FA-BRCA network activation (e.g., Jacquemont and Taniguchi, 2007), to express βADH by transduction with an ADH1B cDNA. We refer to these cells as HeLa-ADH1B cells. The ADH1B gene is expressed at high levels in the liver, and is also the most highly expressed Class I ADH in human mammary tissue (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/ESTProfileViewer.cgi?uglist=Hs.4 see also (Triano et al., 2003)). The ADH1B cDNA we used is derived from the ADH1B*2 allele, which is most common in Asian populations, but also found in the Ashkenazi Jewish population as well. The ADH1B*2 allele encodes β2 ADH protein, which has a higher specific activity for ethanol oxidation than β1ADH or β3ADH, with an intermediate Km for ethanol (Crabb et al., 2004).

Here we show that exposure of HeLa-ADH1B cells to ethanol, at concentrations within the range produced in the human body during social drinking (Zakhari, 2006), results in a significant increase in acetaldehyde-DNA adducts, and activation of the FA-BRCA DNA damage response network. Both effects were blocked by a chemical inhibitor of ADH, demonstrating that ethanol metabolism to acetaldehyde was required. In addition, we found that in cells expressing both ADH and ALDH2, exposure to 20 mM EtOH for 24 hours resulted in increased FANCD2 monoubiquitantion. The implications of these results for alcohol-related breast and liver cancer are discussed.

Results

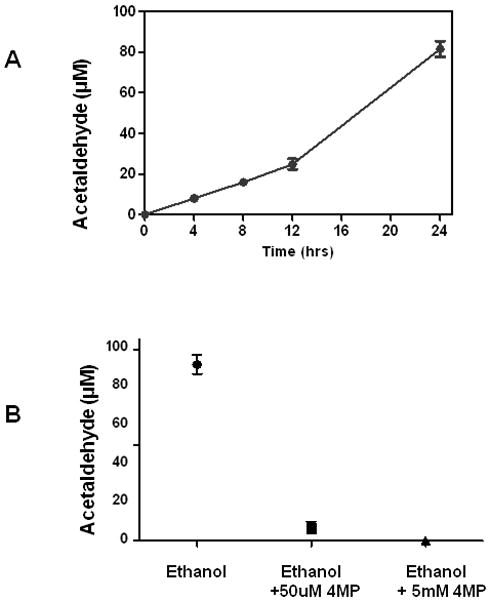

Ethanol is metabolized to acetaldehyde in HeLa-ADH1B cells

Recombinant HeLa-ADH1B cells were produced by retroviral transduction as described previously (Galli et al., 1999). These cells express ADH by Western blotting and enzymatic assay, and generate acetaldehyde from ethanol in culture (Matsumoto et al., 2011). To assess ADH function in vivo, HeLa-ADH1B cells were incubated in 20 mM ethanol in a gas-tight flask, and media collected at various times and assayed for acetaldehyde. As shown in Fig. 1A, in the presence of ethanol, acetaldehyde accumulated in the media over time, verifying that expressed ADH1B was active in the cells under these conditions. The ADH inhibitor 4-methyl pyrazole (4-MP) prevented the accumulation of acetaldehyde in the media, indicating that the acetaldehyde results from ethanol metabolism by ADH (Fig. 1B). These acetaldehyde levels are lower than those reported by Matsumoto et al., but in that study, the cultures contained about 10-fold higher cell densities in order to detect changes in medium ethanol concentration.

Fig. 1.

(A) Acetaldehyde concentration in the media of HeLa-ADH1B cells after exposure to 20 mM ethanol. No acetaldehyde was detectable in cells incubated without ethanol. (B) Effect of differing concentrations of 4-MP on the accumulation of acetaldehyde. Values are means± S.E.M from three cultures.

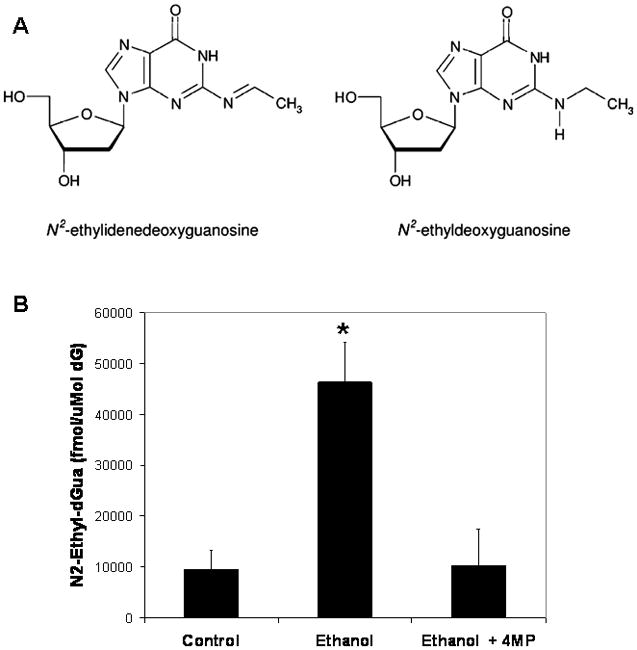

Ethanol metabolism to acetaldehyde generates acetaldehyde-DNA adducts

We next exposed HeLa-ADH1B cells to ethanol with and without 4-MP, and assayed the levels of N2-ethylidene-dGuo, the primary acetaldehyde-DNA adduct in genomic DNA. N2-ethylidene-dGuo was measured as the stable NaBH3CN reduction product N2-ethyl-dGuo (Fig. 2A) using our established liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry-selected reaction monitoring (LC-ESI-MS/MS-SRM) method (Balbo et al., 2008). As shown in Fig. 2B, exposure of HeLa-ADH1B cells to 20 mM ethanol produced an approximately 4-fold increase in the level of N2-ethylidene-dGuo. The increased adduct level was blocked by 4-MP, indicating that the intracellular metabolism of ethanol into acetaldehyde results in the formation of acetaldehyde–DNA adducts.

Fig. 2.

(A) Chemical structures of N2-ethylidene-dGuo and the stable NaBH3CN reduction product N2-ethyl-dGuo. (B) Levels of N2-ethyl-dGuo (fmol/μmol dGuo) in DNA extracted from HeLa-ADH1B cells that were either not exposed to ethanol, exposed to 20 mM ethanol, or exposed to 20 mM ethanol in the presence of 4-MP. Values are means ± S.D., N=3–4 per group. * p<0.01, t-test.

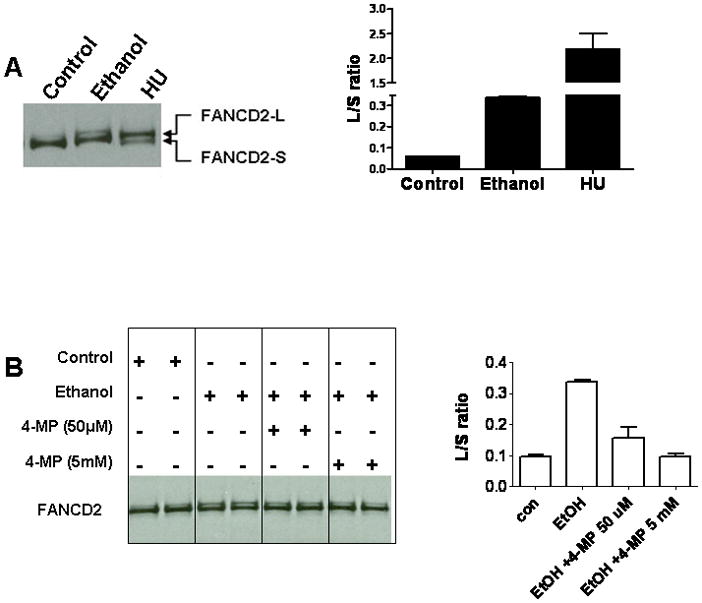

Ethanol metabolism stimulates FANCD2 monoubiquitination and phosphorylation of BRCA1

To test whether ethanol activates the FA-BRCA network in HeLa-ADH1B cells, cells were exposed to ethanol for 24 hours, followed by Western blotting to monitor FANCD2 monoubiquitination (Garcia-Higuera et al., 2001). As shown in Fig. 3A, exposure of cells to 20 mM ethanol resulted in increased FANCD2 monoubiquitination. This increase could be blocked by 4-MP (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Ethanol exposure of HeLa-ADH1B cells stimulates FANCD2 monoubiquitination. (A) Cells were exposed to 20 mM ethanol or 2 mM hydroxyurea (HU) and whole cell extracts probed with anti-FANCD2. The positions of the long (L) and short (S) forms of FANCD2 are indicated. The ratio of the L and S forms of FANCD2 was determined using the NIH ImageJ program and results shown at the right. (B) Cells were exposed to media alone, 20 mM ethanol or 20 mM ethanol in the presence of different concentrations of 4-MP, and extracts analyzed for FANCD2 monoubiquitination. Quantification is shown at the right.

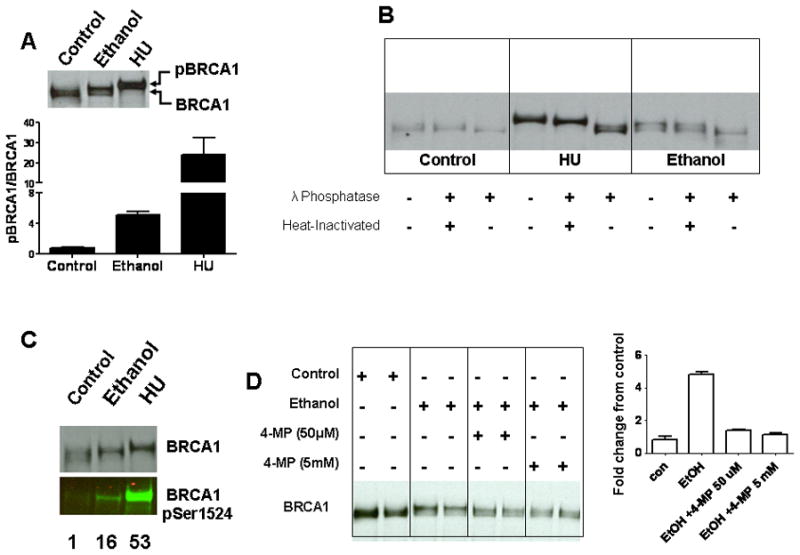

We also examined the effect of ethanol on BRCA1 phosphorylation in HeLa-ADH1B cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, exposure to ethanol resulted in a retardation of BRCA1 gel mobility, indicative of phosphorylation. The change in BRCA1 mobility was reversed by lambda phosphatase, verifying that it was due to phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). Consistent with this result, and our previous findings (Marietta et al., 2009), BRCA1 was found to be phosphorylated on Ser1524 after ethanol exposure using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies (Fig. 4C). Like FANCD2 monoubiquitination, BRCA1 phosphorylation in response to ethanol was blocked by 4-MP (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Ethanol exposure of HeLa-ADH1B cells stimulated BRCA1 phosphorylation. (A) Cells were exposed to 20 mM ethanol or 2 mM HU for 24 hrs, and extracts were probed with anti-BRCA1. An upward shift in the mobility was seen after ethanol and HU treatment. The positions of the phosphorylated BRCA1 (pBRCA1) and non phosphorylated BRCA1 (BRCA1) are indicated. (B) Treatment with λ-Phosphatase reversed the observed shift in mobility of BRCA1. (C) Blots were probed with BRCA1 and BRCA1 pSer1524. Numbers below each lane show the BRCA1 Ser 1524 normalized to total BRCA1, expressed as fold increase relative to the control condition. (D) Cells were exposed to medium alone, 20 mM ethanol, or 20 mM ethanol in the presence of different concentrations of 4-MP, and extracts analyzed for BRCA1 phosphorylation by mobility shift. Quantification is shown at the right. The pBRCA1/BRCA1 ratio (see panel A) in the control samples was assigned a value of 1, and the data for the other conditions was normalized to the control value.

Ethanol increases FANCD2 monoubiquitnation in HeLa cells expressing both ADH and ALDH2

In addition to Class I ADH, cells in the liver express high levels of ALDH2, which maintains lower steady state acetaldehyde concentrations during alcohol consumption. Expression array studies indicate that the ALDH2 gene is also expressed in mammary tissue (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/ESTProfileViewer.cgi?uglist=Hs.632733). Therefore, we tested the ability of ethanol to activate the FA-BRCA network in HeLa cells expressing both enzymes (Matsumoto et al., 2011). Incubation of HeLa-ADH1B-ALDH2 with ethanol resulted in an acetaldehyde concentration of ≈12 uM in the media at 24 hours. Matsumoto et al. observed a higher value (30 uM) in the same cells after 24 hours of ethanol exposure, but again using higher cell densities.

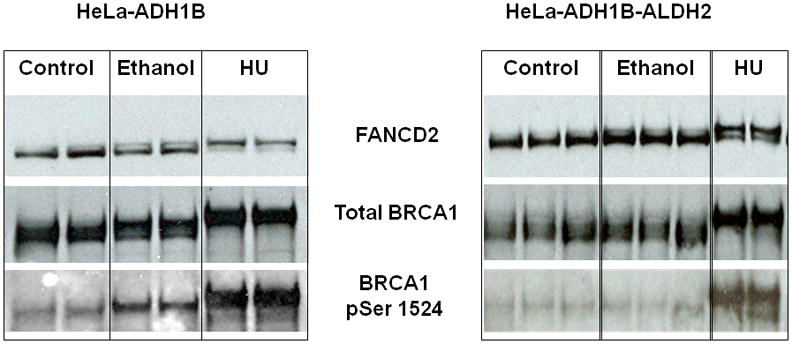

As shown in Figure 5, ethanol increased FANCD2 monoubiquitination in both HeLa-ADH1B and HeLa-ADH1B-ALDH2 cells. In contrast, increased BRCA1 phosphorylation at Ser 1524 was only detectable in HeLa-ADH1B cells but not in HeLa-ADH1B-ALDH2 cells exposed to ethanol. These results indicate that even in cells with active ALDH2, sufficient acetaldehyde can reach the cell nucleus to activate a DNA damage response, as indicated by FANCD2 monoubiquitination.

Fig. 5.

FANCD2 monoubiquitination and BRCA1 phosphorylation following ethanol exposure in HeLa-ADH1B and HeLa- ADH1B-ALDH2 cells. Increased FANCD2 monoubiquitination is seen in both HeLa-ADH1B cells and HeLa-ADH1B-ALDH2 cells after ethanol exposure, whereas ethanol increased BRCA1 phosphorylation at Ser 1524 only in HeLa-ADH1B cells.

Discussion

We previously reported that exposure of human cells to acetaldehyde increased FANCD2 monoubiquitination and BRCA1 phosphorylation. The present results confirm and extend these finding to acetaldehyde generated by ethanol metabolism in situ. Both the increase in DNA adducts and FA-BRCA network activation seen in HeLa-ADH1B cells following ethanol exposure were blocked by the ADH inhibitor 4-MP, indicating that intracellular metabolism of ethanol to acetaldehyde was required. While metabolism of ethanol to acetaldehyde also raises the NADH/NAD+ ratio, and this would also be blocked by 4-MP, it is not clear how this could lead to activation of a DNA damage response. In contrast, as we have previously shown that acetaldehyde activates the FA-BRCA network in human cells under condition where metabolism does not occur, the most parsimonious explanation for the data is that activation of the FA-BRCA network is the result of acetaldehyde-DNA damage. However, the possibility that redox alterations or other effects of ethanol metabolism could modify the DNA damage response cannot be excluded.

In HeLa-ADH1B-ALDH2 cells, ethanol treatment resulted in FANCD2 monoubiquitinaton, indicating that even the low concentration of acetaldehyde generated in these cells is sufficient to generate a DNA damage response. NADH generation would be expected to be even higher in the HeLa-ADH1B-ALDH2 cells than HeLa-ADH1B cells, since there is NADH generated at each step in metabolism. The lack of BRCA1 phosphorylation can be rationalized in view of data showing that recruitment of the FA proteins to a single DNA crosslink can occur in the absence of replication, whereas recruitment of the BRCA proteins requires stalled replication forks (Shen et al., 2009). Acetaldehyde can produce DNA cross-links via the formation of CrPdG adducts in certain sequence contexts (Brooks and Theruvathu, 2005). Therefore, a plausible explanation for our results in the FANCD2 monoubiquitination was the result of formation of a small number of DNA interstrand cross-links in both replicating and non-S phase cells, whereas the total number of stalled replication forks produced under these conditions was insufficient to cause detectable BRCA1 phosphorylation.

In these studies, we used 20 mM ethanol, a concentration that is within the range that can be attained in the human body after social drinking (Zakhari, 2006). The steady-state levels of acetaldehyde generated by HeLa-ADH1B cells after 24 hours of ethanol incubation are quite high compared to the levels produced in the human body during alcohol drinking. On the other hand, in Hela-ADH1B cells, we only observed a 4-fold increase in N2-ethylidene-dGuo levels after ethanol. In contrast, chronic exposure to ethanol in the drinking water led to a ≈40-fold increase in the levels of the same adduct in the liver of Aldh2−/− mice (Matsuda et al., 2007). Furthermore, EtOH increased FANCD2 monoubiquitination in cells expressing both ADH1B and ALDH2, where acetaldehyde levels in the media were roughly 12 uM. Such concentrations have been measured in hepatic tissue and venous blood in animal models (Eriksson and Sippel, 1977, Yao et al., 2010). It should be noted here that acetaldehyde levels measured in the blood in vivo, and in the tissue culture media in vitro, are dilutions of the intracellular levels. As such, it is possible that these levels would be achieved within individual cells expressing more ADH than ALDH2. These observations suggest that activation of the FA-BRCA network is quite sensitive to DNA damage resulting from acetaldehyde. Therefore, DNA damage subsequent to ethanol metabolism as demonstrated here may be relevant to the genotoxic effects of alcohol consumption in vivo, at least under some conditions. More work in animal models, and ultimately with human samples will be necessary to fully understand the quantitative and temporal relationship between ethanol consumption, DNA damage, and FA-BRCA network activation and alcohol-related carcinogenesis.

The FA-BRCA network is activated in response to replication-blocking DNA damage. Our observation of increased levels of the acetaldehyde-DNA adduct N2-ethylidene-dGuo demonstrates that acetaldehyde formed intracellularly was able to gain access to the cell nucleus, and it is therefore likely that in addition to N2-ethylidene-dGuo, the levels of other acetaldehyde-derived adducts (Brooks and Theruvathu, 2005) were increased as well. The relative contribution of the different acetaldehyde-derived DNA modifications to activation of the FA-BRCA network remains to be determined. We also note that in response to DNA damage, the FA-BRCA network facilitates both homologous recombination, an “error-free” process, as well as an error-prone translesion synthesis mechanism (Moldovan and D’Andrea, 2009). Therefore, activation of the FA-BRCA network is not only an indication of genotoxic damage, but also an indicator of a cellular response that may itself be pro-mutagenic.

Rulten et al. (2008) found that ethanol and acetaldehyde increased the overall level of FANCD2 protein in mouse brain and human neuronal cells, without increasing FANCD2 monoubiquitination. However, it is difficult to directly compare the two data sets in view of the different cell types used. Notably, we found that the effect of ethanol on FANCD2 monoubiquitination depends on its metabolism to acetaldehyde, and therefore our results are in agreement with Rulten et al. that ethanol itself does not increase FANCD2 monoubiquitination.

Implications for alcohol-related cancers

Alcohol drinking increases the risk of cancers of the esophagus, colorectum, liver, and female breast (Baan et al., 2007). Cells in the esophagus and colon can be exposed to high levels of exogenous acetaldehyde from ethanol consumption due to microbial alcohol oxidation (Salaspuro, 2009). In contrast, since blood acetaldehyde levels are very low or undetectable following ethanol drinking (Eriksson, 2007), intracellular metabolism of ethanol is the more physiologically relevant source of acetaldehyde for the female breast and liver during ethanol drinking. Therefore our results showing elevated levels of acetaldehyde-DNA adducts and activation of the FA-BRCA network in HeLa-ADH1B cells are consistent with the hypothesis that DNA adducts resulting from the intracellular metabolism of ethanol to acetaldehyde in the human breast could play a role in alcohol-related breast cancer risk. It is important to emphasize however that this mechanism is not mutually exclusive with other proposed mechanisms of alcohol-related breast cancer (Seitz and Stickel, 2007). Indeed, replication blocking and mutagenic DNA damage would be most dangerous in cells undergoing DNA replication, and so if ethanol metabolism to acetaldehyde increases DNA damage, as shown here, and ethanol increases cell proliferation via estrogen signaling (Etique et al., 2004), the two mechanisms would be multiplicative.

We chose the ADH1B*2 allele for these studies since it is the most active Class 1 ADH at the usual blood ethanol concentrations observed during social drinking. Directly relating this allele to alcohol-related breast cancer is complicated by the fact that carriage of this allele reduces alcohol drinking and alcoholism (Thomasson et al., 1991, Crabb et al., 2004), most likely due to its effect on systemic ethanol metabolism. While Kawase et al. (Kawase et al., 2009) failed to detect a relationship between alcohol drinking, the ADH1B*2 allele, and breast cancer, in that study heavy drinking was defined as >15 g of ethanol/day (Kawase et al., 2009). This level of consumption would be classified as low in studies relating the ALDH2*2 allele to esophageal cancer risk (Brooks et al., 2009). This comparison is relevant because like ADH1B*2, carriage of the ALDH2*2 allele reduces alcohol consumption due to the flushing response, but dramatically elevated cancer risks are observed in those ALDH2-deficient individuals who overcome the aversive effect and become heavy drinkers (Yokoyama et al., 1996, Brooks et al., 2009). Therefore, the significance of acetaldehyde for breast cancer in heavy drinking women with the ADH1B*2 allele remains to be assessed. The effect of the ADH1C polymorphism on alcohol-related breast cancer risk is only observed in individuals with ethanol consumption above a threshold level (Seitz and Becker, 2007), and this may be the case with ADH1B*2 as well.

The other tissue where acetaldehyde derived from intracellular ethanol metabolism could affect cancer risk is the liver, which is the major site of ethanol metabolism in the body. However, while ethanol drinking clearly increases the risk of HCC, other factors such as cirrhosis or hepatitis infection are also involved (Poschl and Seitz, 2004). Mutagenic DNA damage from acetaldehyde (as well as other adducts (Frank et al., 2004)) in quiescent hepatocytes could be of limited significance in the absence of DNA replication, but may become significant when cells are stimulated to divide as a result of liver injury due to cirrhosis or hepatitis.

Finally, our results have implications for identifying individuals who are at differential risk for alcohol-related cancers. Specifically our observations provide a framework for molecular genetic epidemiology studies to test the hypothesis that individuals carrying functional SNPs in the genes controlling alcohol metabolism and encoding FA-BRCA network proteins (Barroso et al., 2009) may be at elevated risk of breast and liver cancer from ethanol consumption. Such information could have important consequences for cancer prevention.

Materials and Methods

Cells and media

The construction and characterization of HeLa-ADH1B and Hela-ADH1B-ALDH2 cells have been described elsewhere (Matsumoto et al., 2011). Tissue culture reagents and G418 were purchased from Invitrogen. HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in minimum essential medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 63 ug/ml penicillin, and 100 ug/ml streptomycin.

Ethanol exposure

One day before ethanol exposures, ≈1.2×106 cells were seeded into T-25 flasks. On the day of the experiment, media was removed and the cells washed twice, then 10 ml of experimental media was added to the flasks, caps were tightly closed, sealed with Parafilm™ and incubated at 37 °C.

For treatment of cells, MEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM glutamine was used, with the addition of 20 mM ethanol or 2 mM hydroxyurea (HU) as a positive control. Following incubation, an aliquot of the media was collected into pre-chilled microfuge tubes, frozen immediately in dry ice, and stored at −80°C for determination of acetaldehyde. Cells were collected and frozen at −80°C.

Acetaldehyde Assay

Acetaldehyde production was measured using the Acetaldehyde Assay Kit (Megazyme, Bray, Ireland) in 96-well plates. Acetaldehyde ammonia trimer was used as the standard according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Extract Preparation and Western Blotting

Extract preparation, lambda phosphatase treatment, and Western blotting were carried out as described previously (Marietta et al., 2009). Blots were probed with antibodies against FANCD2 (Novus), BRCA1 (Ab-1, Calbiochem), or BRCA1 pSer 1524 (Bethyl Laboratories). For quantification, X-ray films were scanned and analyzed using the NIH ImageJ program. Unless otherwise stated, values shown are means ± S.E.M. from three replicate cultures. The color image of the pSer1524 signal in Fig. 3D was obtained using an AlphaImager (Alpha-Innotech, now Cell Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA).

N2-Ethyl-dGuo quantitation

DNA extraction, DNA enzymatic hydrolysis and sample enrichment and analysis by LC-ESI-MS/MS-SRM were carried out as previously described (Balbo et al., 2008). Buffer blanks containing 15N labeled internal standard were analyzed to check instrument base line and rule out possible contamination. Calf thymus DNA (50 μg) with internal standard added was used as a positive control to determine inter-day precision and accuracy. Samples were run together with one buffer blank and 3 positive controls.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cheryl Marietta for technical advice and comments, and Dr. Steven Hecht for his support. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism through the Intramural Research Program (PJB) and grants R01 AA15070 and P60 AA07611 (to DWC).

References

- Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Altieri A, Cogliano V. Carcinogenicity of alcoholic beverages. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:292–3. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(07)70099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbo S, Hashibe M, Gundy S, Brennan P, Canova C, Simonato L, Merletti F, Richiardi L, Agudo A, Castellsague X, Znaor A, Talamini R, Bencko V, Holcatova I, Wang M, Hecht SS, Boffetta P. N2-ethyldeoxyguanosine as a potential biomarker for assessing effects of alcohol consumption on DNA. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3026–32. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso E, Pita G, Arias JI, Menendez P, Zamora P, Blanco M, Benitez J, Ribas G. The Fanconi anemia family of genes and its correlation with breast cancer susceptibility and breast cancer features. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:655–60. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PJ, Theruvathu JA. DNA adducts from acetaldehyde: implications for alcohol-related carcinogenesis. Alcohol. 2005;35:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb DW, Matsumoto M, Chang D, You M. Overview of the role of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase and their variants in the genesis of alcohol-related pathology. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:49–63. doi: 10.1079/pns2003327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue TM, Jr, Clemens DL, Galli A, Crabb D, Nieto N, Kato J, Barve SS. Use of cultured cells in assessing ethanol toxicity and ethanol-related metabolism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:87S–93S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu RG, Shields PG. The etiology of alcohol-induced breast cancer. Alcohol. 2005;35:213–25. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson CJ. Measurement of acetaldehyde: what levels occur naturally and in response to alcohol? Novartis Found Symp. 2007;285:247–55. doi: 10.1002/9780470511848.ch18. discussion 256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson CJ, Sippel HW. The distribution and metabolism of acetaldehyde in rats during ethanol oxidation-I. The distribution of acetaldehyde in liver, brain, blood and breath. Biochem Pharmacol. 1977;26:241–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(77)90310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etique N, Chardard D, Chesnel A, Merlin JL, Flament S, Grillier-Vuissoz I. Ethanol stimulates proliferation, ERalpha and aromatase expression in MCF–7 human breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2004;13:149–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A, Seitz HK, Bartsch H, Frank N, Nair J. Immunohistochemical detection of 1, N6-ethenodeoxyadenosine in nuclei of human liver affected by diseases predisposing to hepato-carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1027–31. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli A, Price D, Crabb D. High-level expression of rat class I alcohol dehydrogenase is sufficient for ethanol-induced fat accumulation in transduced HeLa cells. Hepatology. 1999;29:1164–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, Meyn MS, Timmers C, Hejna J, Grompe M, D’andrea AD. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:249–62. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemont C, Taniguchi T. Proteasome function is required for DNA damage response and fanconi anemia pathway activation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7395–405. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase T, Matsuo K, Hiraki A, Suzuki T, Watanabe M, Iwata H, Tanaka H, Tajima K. Interaction of the effects of alcohol drinking and polymorphisms in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes on the risk of female breast cancer in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2009;19:244–50. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20081035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marietta C, Thompson LH, Lamerdin JE, Brooks PJ. Acetaldehyde stimulates FANCD2 monoubiquitination, H2AX phosphorylation, and BRCA1 phosphorylation in human cells in vitro: implications for alcohol-related carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2009;664:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Matsumoto A, Uchida M, Kanaly RA, Misaki K, Shibutani S, Kawamoto T, Kitagawa K, Nakayama KI, Tomokuni K, Ichiba M. Increased formation of hepatic N2-ethylidene-2′-deoxyguanosine DNA adducts in aldehyde dehydrogenase 2-knockout mice treated with ethanol. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2363–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Yabushita H, Kanaly RA, Shibutani S, Yokoyama A. Increased DNA damage in ALDH2-deficient alcoholics. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:1374–8. doi: 10.1021/tx060113h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Cyganek I, Sanghani PC, Cho WK, Liangpunsakul S, Crabb DW. Ethanol metabolism by HeLa cells transduced with human alcohol dehydrogenase isoenzymes: control of the pathway by acetaldehyde concentration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:28–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan GL, D’andrea AD. How the fanconi anemia pathway guards the genome. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:223–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayoshi H, Matsumoto A, Nishi R, Kawamoto T, Ichiba M, Matsuda T. Increased formation of gastric N(2)-ethylidene-2′-deoxyguanosine DNA adducts in aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 knockout mice treated with ethanol. Mutat Res. 2009;673:74–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poschl G, Seitz HK. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:155–65. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulten SL, Hodder E, Ripley TL, Stephens DN, Mayne LV. Alcohol induces DNA damage and the Fanconi anemia D2 protein implicating FANCD2 in the DNA damage response pathways in brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1186–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salaspuro M. Acetaldehyde as a common denominator and cumulative carcinogen in digestive tract cancers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:912–25. doi: 10.1080/00365520902912563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard Y, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. A review of human carcinogens—Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncology. 2009;10:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz HK, Becker P. Alcohol metabolism and cancer risk. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30:38–41. 44–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz HK, Stickel F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrc2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Do H, Li Y, Chung WH, Tomasz M, De Winter JP, Xia B, Elledge SJ, Wang W, Li L. Recruitment of fanconi anemia and breast cancer proteins to DNA damage sites is differentially governed by replication. Mol Cell. 2009;35:716–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson HR, Edenberg HJ, Crabb DW, Mai XL, Jerome RE, Li TK, Wang SP, Lin YT, Lu RB, Yin SJ. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes and alcoholism in Chinese men. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:677–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triano EA, Slusher LB, Atkins TA, Beneski JT, Gestl SA, Zolfaghari R, Polavarapu R, Frauenhoffer E, Weisz J. Class I alcohol dehydrogenase is highly expressed in normal human mammary epithelium but not in invasive breast cancer: implications for breast carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3092–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Emergence of a DNA-damage response network consisting of Fanconi anaemia and BRCA proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:735–48. doi: 10.1038/nrg2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao CT, Lai CL, Hsieh HS, Chi CW, Yin SJ. Establishment of steady-state metabolism of ethanol in perfused rat liver: the quantitative analysis using kinetic mechanism-based rate equations of alcohol dehydrogenase. Alcohol. 2010;44:541–51. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A, Muramatsu T, Ohmori T, Higuchi S, Hayashida M, Ishii H. Esophageal cancer and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotypes in Japanese males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakhari S. Overview: How Is Alcohol Metabolized by the Body? Alcohol Research and Health. 2006;29:245–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]