Abstract

We report a misleading outcome of colonic transit time (CTT) assessment in an adolescent girl with functional constipation. We found prolonged total and right segmental CTT despite high doses of oral polyethylene glycol 4000 and repeated treatment with polyethylene glycol–electrolyte solution (Klean-Prep®) by nasogastric tube. A colonoscopy aiming at disimpaction of a possible faecal mass revealed an empty colon with dozens of radio-opaque markers adhered to the colonic wall. This report shows that the result of a CTT cannot be accepted blindly. Especially the clustering of many markers within narrow margins might point at entrapment of markers in mucus against the colonic wall.

Keywords: Constipation, Colonic transit time, Radio-opaque markers

Introduction

Total and segmental colonic transit time (CTT) can be assessed noninvasively using radio-opaque markers. This technique, first described in 1969 by Hinton et al. [6], can also be used to differentiate between patterns of delayed colonic transit and to evaluate the response to treatment [2]. Several methods have been published, differing in the number of markers ingested, in the number of days markers are ingested and in the number and intervals of abdominal X-rays [4, 7].

Methods

CTT was assessed using the method described by Bouchoucha et al. [4]. In this method, the patient swallows one capsule containing 10 radio-opaque markers at the same hour for six consecutive days. On the seventh day, a plain abdominal X-ray is obtained at the same hour as the capsules were swallowed [4]. Interpretation is based on the identification of markers in three regions as defined by bony landmarks and gaseous outlines [1, 4]. By counting the markers in the right, left and rectosigmoid regions, total and segmental CTTs can be calculated according to the formula: CTT (in hours) = sum of markers × 2.4. The upper limits of normal of the total CTT is 62 h [1].

Case history

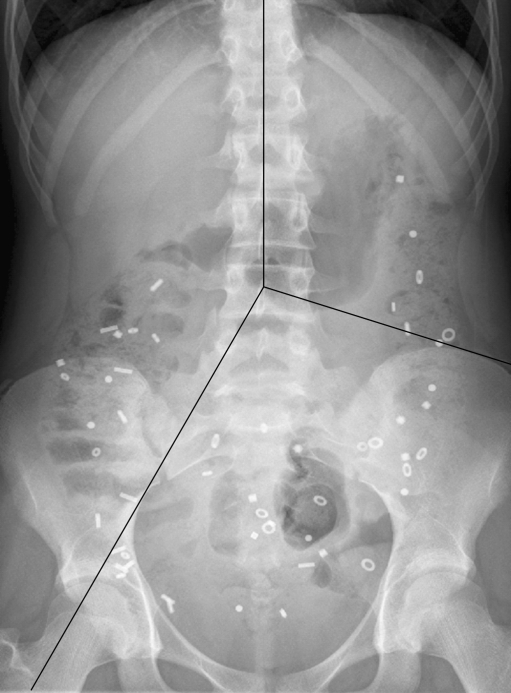

A 16-year-old girl with a long history of urinary tract infections and functional constipation presented with deterioration of her defecation problems following influenza H1N1. Abdominal pain and painful defecation intensified, and the frequency of bowel movements decreased from once every day to twice a week, despite up to 80 g per day of polyethylene glycol 4000. On physical examination multiple masses could be palpated bilaterally in the abdomen which is consistent with faecal retention. Because of the refractory nature of her constipation, a CTT was performed as described above. Total CTT was 124.8 h (52 markers; upper limit of normal 62 h [1]), segmental transit times being 33.6, 16.8 and 74.4 h, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Plain abdominal X-ray during CTT study before bowel cleansing with Klean-Prep®

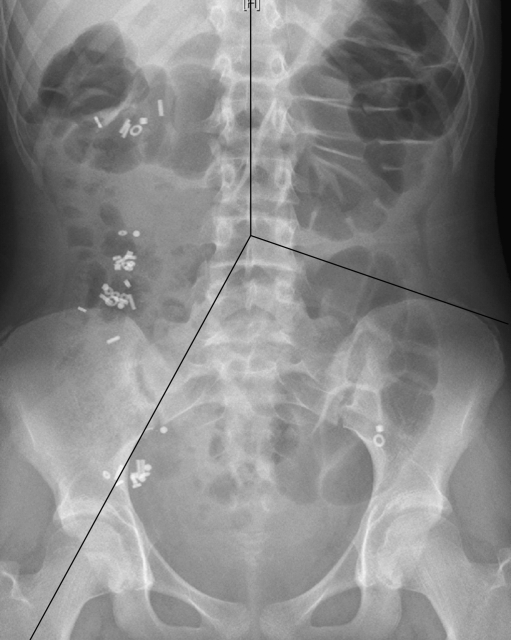

The girl was admitted for bowel cleansing with 4 L of polyethylene glycol–electrolyte solution (Klean-Prep®) by nasogastric tube. Because her symptoms persisted while only clear liquids were seen passing, this treatment was repeated twice in the next week. Back on high doses of oral polyethylene glycol (80 g per day), the girl continued to complain of abdominal pain combined with a low frequency of bowel movements. Although on physical examination the bilateral masses could not be felt anymore, palpation of the abdomen was repeatedly extremely painful. Two months after the first study, therefore, the marker study was repeated. Now 42 markers were found retained, most of them in the right hemicolon, translating into a CTT of 110.8 h, segmental transit times being 72 (right), 0 (left) and 28.8 (rectosigmoid) h (Fig. 2). Because this suggested the presence of a caecal fecaloma, we decided to perform colonoscopy, aiming at disimpaction of the faecal mass, preceded by standard bowel preparation with 4 L of Klean-Prep®. To our surprise the entire colon was empty, while dozens of radio-opaque markers were found clustered in small groups into sticky mucus to all quadrants of the right hemicolon wall (Fig. 3). With some effort they could be flushed from the colonic wall. No further endoscopic abnormalities were encountered, in particular no signs of mucosal disease at the site the markers were found. Therefore, no biopsies were taken during the endoscopy. The abdominal pain subsided over the next few days, and oral laxative medication could eventually be lowered to 10 g of polyethylene glycol per day. Frequency of bowel movements has improved to at least once every other day.

Fig. 2.

Plain abdominal X-ray during CTT study 2 months after bowel cleansing

Fig. 3.

Radio-opaque markers sticking together to the caecum wall as seen during colonoscopy

Discussion

CTT is a useful method to evaluate colonic function both in adults and children. It can aid in the differentiation of defecation disorders such as functional constipation and functional non-retentive faecal soiling. It can also be used when history seems to be unreliable, for example in patients with eating disorders. Studies in adults and children show a strong positive correlation between the severity of symptoms of constipation and CTT, a transit time of over 100 h in children being associated with a poorer outcome of chronic constipation after 1 year [5]. Study results on the effect of bowel cleansing on CTT are contradictory. A study in 25 constipated adults reported unchanged CTT with marker accumulation shifted to the distal colon [3], while in another study in 10 adults, bowel cleansing resulted in significant shortening of CTT, but with unchanged distribution of radio-opaque markers [8]. Clustering of markers, however, has not been described before. This case report shows that markers do not always mix appropriately with faeces and therefore sometimes may not adequately reflect CTT. Apparently, in an empty colon, the markers can be caught in mucus and stick to the colonic wall for a longer period, even when it is followed by the normal passage of faeces. Looking back to the X-rays, the typical pattern of clustering of the markers should probably have been interpretated as a sign of entrapment.

In conclusion, while CTT assessment using radio-opaque markers can be applied successfully in the investigation of defecation disorders, the results cannot be accepted blindly. Especially the clustering of many markers within narrow margins might point at entrapment of markers against the colonic wall.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest or financial interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Arhan P, Devroede G, Jehannin B, Lanza M, Faverdin C, Dornic C, Persoz B, Tétreault L, Perey B, Pellerin D. Segmental colonic transit time. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:625–629. doi: 10.1007/BF02605761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benninga MA, Büller HA, Tytgat GN, Akkermans LM, Bossuyt PM, Taminiau JA. Colonic transit time in constipated children: does pediatric slow-transit constipation exist? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23:241–251. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergin AJ, Read NW. The effect of preliminary bowel preparation on a simple test of colonic transit in constipated subjects. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993;8(2):75–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00299331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchoucha M, Devroede G, Arhan P, Strom B, Weber J, Cugnenc PH, Denis P, Barbier JP. What is the meaning of colorectal transit time measurement? Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:773–782. doi: 10.1007/BF02050328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Lorijn F, Van Wijk MP, Reitsma JB, Van Ginkel R, Taminiau JA, Benninga MA. Prognosis of constipation: clinical factors and colonic transit time. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:723–727. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.040220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinton JM, Lennard-Jones JE, Young AC. A new method for studying gut transit times using radioopaque markers. Gut. 1969;10:842–847. doi: 10.1136/gut.10.10.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metcalf AM, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR, MacCarty RL, Beart RW, Wolff BG. Simplified assessment of segmental colonic transit. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:40–47. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sloots CE, Felt-Bersma RJ. Effect of bowel cleansing on colonic transit in constipation due to slow transit or evacuation disorder. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:55–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]