Abstract

O6-POB-dG (O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]deoxyguanosine) are promutagenic nucleobase adducts that arise from DNA alkylation by metabolically activated tobacco-specific nitrosamines such as 4-(methylnitrosamino)- 1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N-nitrosonicotine (NNN). If not repaired, O6-POB-dG adducts cause mispairing during DNA replication, leading to G → A and G → T mutations. A specialized DNA repair protein, O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase (AGT), transfers the POB group from O6-POB-dG in DNA to a cysteine residue within the protein (Cys145), thus restoring normal guanine and preventing mutagenesis. The rates of AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG may be affected by local DNA sequence context, potentially leading to adduct accumulation and increased mutagenesis at specific sites within the genome. In the present work, isotope dilution high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS)-based methodology was developed to investigate the influence of DNA sequence on the kinetics of AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG adducts. In our approach, synthetic DNA duplexes containing O6-POB-dG at a specified site are incubated with recombinant human AGT protein for defined periods of time. Following spiking with D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard and mild acid hydrolysis to release O6-POB-guanine (O6-POB-G) and D4-O6-POB-guanine (D4-O6-POB-G), samples are purified by solid phase extraction (SPE), and O6-POB-G adducts remaining in DNA are quantified by capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS. The new method was validated by analyzing mixtures containing known amounts of O6-POB-dG-containig DNA and the corresponding unmodified DNA duplexes and by examining the kinetics of alkyl transfer in the presence of increasing amounts of AGT protein. The disappearance of O6-POB-dG from DNA was accompanied by pyridyloxobutylation of AGT Cys-145 as determined by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS of tryptic peptides. The applicability of the new approach was shown by determining the second order kinetics of AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG adducts placed within a DNA duplex representing modified rat H-ras sequence (5′-AATAGTATCT[O6-POB-G]GAGCC-3′) opposite either C or T. Faster rates of alkyl transfer were observed when O6-POB-dG was paired with T rather than C (k = 1.74 × 106 M−1s−1 vs 1.17 × 106 M−1s−1).

Introduction

4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK)* and N-nitrosonicotine (NNN) are carcinogenic nitrosamines found only in tobacco products and known to specifically induce lung cancer in laboratory animals.1-3 The carcinogenic effects of NNK and NNN are mediated by the formation of promutagenic DNA adducts. Both tobacco-specific nitrosamines undergo cytochrome P450 monooxygenase-mediated bioactivation to form pyridyloxobutyl diazonium ions which react with nucleophilic sites in DNA. The resulting bulky pyridyloxobutylated nucleobase lesions include N7-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)-but-1-yl]deoxyguanosine (N7-POB-dG), O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]deoxyguanosine (O6-POB-dG), O2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]thymidine (O2-POB-T), and O2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-deoxycytidine (O2-POB-dC).3,4 Among these, O6-POB-dG have been shown to be strongly mutagenic. During replication, DNA polymerases incorporate either thymine or adenine opposite O6-POB-dG in lieu of the correct base (cytosine), leading to G → A transitions and G → T transversions.5

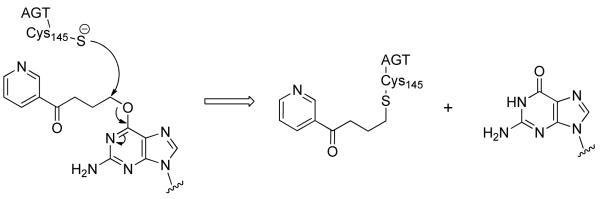

In order to prevent mutagenesis, O6-POB-dG lesions must be efficiently repaired prior to DNA replication. A specialized DNA repair protein, O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT), directly removes the O6 -alkyl group from modified guanine such as O6-POB-G, restoring the native DNA structure.6-8 Upon AGT binding to double-stranded DNA, the O6-alkylguanosine residue is flipped out of the DNA base stack to enter the active site of the AGT protein.9 Histidine-146 residue in the AGT active site, with the aid of a water molecule, acts as a general base to abstract a proton from the thiol group of a neighboring cysteine-145 (Cys145).6,9 The resulting thiolate anion accepts the alkyl group from O6-alkylguanosine, restoring normal guanine and forming a thioether at Cys145 (Scheme 1). This inactivates the AGT protein by inducing conformational changes, ubiquitination, and proteosomal degradation.10,11 As a result, the AGT repair reaction is stoichiometric, inactivating one molecule of AGT protein per each alkylguanine lesion repaired.

Scheme 1.

AGT repair of O6-pyridyloxobutyl-dG adducts in DNA

All available evidence suggests that alkylated AGT molecules are not re-activated but are rapidly degraded by the proteasome. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain this unusual mechanism,8,12 which may relate to the difficulty of distinguishing O6-methylguanine from unmodified guanine at a high enough level of discrimination to prevent damage to normal DNA.8 Furthermore, although one molecule of protein is used up per adduct repaired, only a single protein is needed as compared to over 20 proteins in the nucleotide excision repair mechanism. Finally, the alkylated protein must be degraded quickly because it retains its DNA-binding abilities and may interfere with repair of additional O6-alkylguanine lesions.

While several studies have reported that the rates of AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG lesions are affected by neighboring DNA bases, only a few selected DNA sequences have been examined.13,14 Coulter et. al. used a radioflow HPLC-based methodology to show that the first order rate for AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG placed in the first position of the H-ras codon 12 (5′-CTXGA-3′ context, 0.95 × 10−4 s−1) was ~ 6 times larger for the adduct placed at the second position of codon 12 (5′TGXAG-3′ context, 0.16 × 10−4 s−1).14 A much faster repair rate (0.022 s−1) was observed for another sequence containing O6-POB-dG (X) in 5′-ATXGC-4′ sequence context.14 Similar results were reported by Mijal et. al.13 who employed denaturing PAGE to examine the kinetics of AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG adducts relative to O6-Me-dG within rat H-ras codon 12. These authors13 also noted that the rate of O6-POB-dG repair increased when a thymine rather than cytosine was placed in the complementary strand opposite O6-alkyl-dG. However, to our knowledge, no systematic studies have been conducted to examine the effects of local DNA sequence on AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG, probably due to practical limitations of the available experimental methodologies. Previous studies have relied on the ability of HPLC or gel electrophoresis methodologies to resolve alkylated and dealkylated DNA strands.13,14 Such separations can be quite challenging, especially for longer DNA duplexes (> 20 nucleotides).

In the present work, a novel, stable isotope dilution capillary HPLC electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI+-MS/MS) methodology was developed to analyze the kinetics of AGT repair of O6-POB-dG adducts in vitro as a function of DNA sequence context. An application of this new methodology was demonstrated for O6-POB-dG lesions introduced into synthetic oligonucleotide duplexes representing p53 codon 158 and a modified rat H-ras gene sequence containing codon 12.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

Dithiane protected O6-POB-dG (O6-[3-[2-(3-pyridyl)-1,3-dithyan-2-yl]propyl]-deoxyguanosine) was synthesized according to methods published by Wang and coworkers15 and converted to 5′-dimethoxytrityl-N,N-dimethyl-formamidine-O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]-2′-deoxyguanosine, 3′-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite by standard phosphoramidite chemistry.15,16 All other nucleoside phosphoramidites, solvents, and solid supports required for the solid phase synthesis of DNA were procured from Glen Research Corporation (Sterling, VA). Human recombinant AGT protein with a C-terminal histidine tail (WT ch-AGT) was expressed in E. coli and isolated as reported previously.17,18 The catalytic activity of the AGT protein was determined by incubating with known amounts of DNA duplexes containing O6-MeG.19 Approximately 75% of the total protein was active, depending on the aliquot. D4-O6-POB-dG was a gift from Professor Stephen Hecht (University of Minnesota). O6-POB-dG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide representing a modified rat H-ras gene sequence was generously provided by Professor Lisa Peterson (University of Minnesota). Phosphodiesterase I, phosphodiesterase II, and DNase I were obtained from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ). Trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI), and bovine intestinal alkaline phosphatase was procured from Sigma Aldrich Chemical Company (Milwaukee, WI). The rest of the chemicals were purchased either from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ) or Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI).

Solid Phase Synthesis of DNA

Synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides containing O6-[3-[2-(3-pyridyl)-1,3-dithian-2-yl]propyl]-deoxyguanosine in the context of p53 codon 158 were prepared by solid phase synthesis on a DNA synthesizer16 starting with synthetic 5′-dimethoxytrityl-N,N-dimethyl-formamidine-O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]-2′-deoxyguanosine, 3′-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite.15 Following HPLC purification of synthetic oligonucleotides, the 1,3-dithiane protective group was removed with N-chlorosuccinimide to produce the corresponding O6-POB-G-containing DNA.15,20

Synthetic DNA oligomers were purified by reversed phase HPLC using an Agilent 1100 HPLC system interfaced with a DAD UV detector.21,22 HPLC fractions corresponding to oligodeoxynucleotides of interest were collected and concentrated under reduced pressure. The presence of O6-POB-dG was confirmed by capillary HPLC-ESI− MS (Table 1).22-24 Oligonucleotide concentrations were determined from the amounts of 2′-deoxyguanosine present in enzymatic digests using a previously published protocol.19,25,26

Table 1.

Nucleobase sequence and molecular weight information (from HPLC2ESI22MS) for synthetic DNA oligomers employed in this work.

| Oligomer | Sequence | Molecular Weight |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Observed | ||

| (+) p53 codon 158-O6pobG | ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC | 6026.0 | 6026.9 |

| (−) p53 codon 158 | GGCCATGGC GCG GACGCGGGT | 6529.3 | 6529.4 |

| (+) p53 codon 158 | ACCCGCGTCCGCGCCATGGCC | 6329.1 | 6328.8 |

| (+) H-ras POB | AATAGTATCT[O6-POB-G]GAGCC | 5052.3 | 5051.7 |

| (−) H-ras base paired dC | GGCTCCAGATACTATT | 4856.2 | 4855.6 |

| (−) H-ras base paired dT | GGCTCTAGATACTATT | 4871.2 | 4870.7 |

O6-POB-dG containing DNA duplexes were prepared by mixing equal amounts of the complimentary strands in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) buffer containing 50 mM NaCl to achieve a final concentration of 200 μM, followed by heating at 90 °C for 5 minutes and slow cooling to room temperature.25

AGT reactions with O6-POB-dG containing DNA Duplexes

DNA duplexes containing O6-POB-dG (500 fmol, Table 1) were mixed with human recombinant AGT protein (400 fmol) in a final volume of 90 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and 0.5 mM DTT. Following incubation at room temperature for fixed periods of time (0-50 seconds), repair reactions were manually quenched with 0.2 N HCl. D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard (250 fmol) was added, and the DNA was subjected to mild acid hydrolysis (0.1 N HCl, 70 °C for 1 h). Samples were neutralized with ammonium hydroxide. O6-POB-G adducts were isolated by solid phase extraction (SPE) and quantified by the capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described below.

Solid Phase Extraction

Solid phase extraction (SPE) was conducted with Strata-X cartridges (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), which were pre-equilibrated with methanol and water. Following loading of DNA hydrolysates, cartridges were washed with 20% methanol in water. O6-POB-G and D4-O6-POB-G were eluted with 100% MeOH. Samples were dried under reduced pressure, re-suspended in 15mM NH4OAc (pH 5.5) containing 10% acetonitrile, and analyzed by the capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described below.

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS Analysis of O6-POB-G Adducts

Capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analyses were conducted using a Thermo-Finnigan Ultra TSQ mass spectrometer interfaced with a Waters Acquity capillary HPLC system. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ion mode. Typical spray voltage was 3.3 kV, and a capillary temperature was 250 °C. Typical tube lens offset was 91 V, and nitrogen was used as a sheath gas (43 counts). Quantitative analyses were conducted in the SRM mode, with collision energy of 13 V. Argon was used as a collision gas with a pressure of 1 mTorr. MS/MS analyses were performed with a scan width of 0.4 m/z and a scan time of 0.25 seconds.

Capillary HPLC was conducted using a Zorbax SB C18 column (0.5 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm, Agilent Technologies) eluted at a flow rate of 15 μL/min and maintained at 25°C. HPLC solvents were 15 mM ammonium acetate (A) and acetonitrile containing 15 mM ammonium acetate (10%, B). A linear gradient of 11% to 34% B in 16 minutes was used, followed by isocratic elution at 34% B for 4 minutes and column re-equilibriation.26 Under these conditions, both O6-POB-G and its internal standard (D4-O6-POB-G) eluted at ~ 14 minutes. Selected reaction monitoring (SRM) was conducted by monitoring the transitions: m/z 299.1 [M + H+] →148.1 [POB]+, m/z 299.1 →152.1 [Gua + H+] for O6-POB-G and m/z 303.1 [M + H+] → m/z 152.1 ([D4-POB]+ and [Gua + H+]) for D4-O6-POB-G.

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS method validation

Synthetic DNA 21-mers (5′-ACCCGCGTC CGCGCCATGGCC-3′, 1 pmol) were spiked with increasing amounts of the corresponding O6-POB-dG-containing duplexes (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′, 0.1-1pmol). DNA mixtures were dissolved in 90 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM EDTA. Following the addition of D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard (250 fmol) and inactivated AGT protein (400 fmol), samples were subjected to mild acid hydrolysis (0.1 N HCl, 70 °C, 1h). The hydrolysates were neutralized with ammonium hydroxide and purified by solid phase extraction on Strata-X cartridges as described above. O6-POB-G and D4-O6-POB-G were eluted with methanol, dried under vacuum, and re-suspended in 15 mM NH4OAc (pH 5.5) containing 10% ACN for capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analyses. The validation results were expressed as the ratio of HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS peak areas corresponding to O6-POB-G and D4-O6-POB-G versus the actual O6-POB-G/D4-O6-POB-G molar ratio. All analyses were performed in quadruplet.

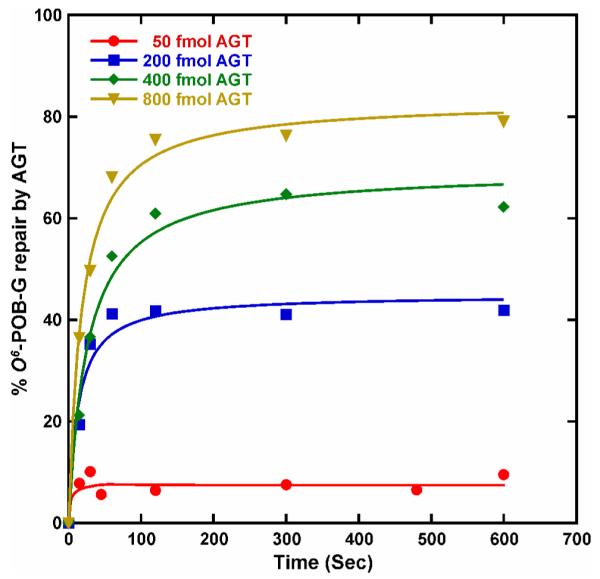

Kinetics of POB Group Transfer in the Presence of Increasing Amounts of AGT

O6-POB G-containing DNA duplexes (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB G]CGCCATGGCC-3′ and its compliment, 0.5 pmol, in triplicate) were dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8) containing 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM EDTA (final volume 90 μl). Following addition of human recombinant AGT protein (50, 200, 400, or 800 fmol), alkyl transfer reactions were allowed to proceed for varying lengths of time (0-600 seconds). Each reaction was terminated by the addition of HCl to achieve the final concentration of 0.1N. After spiking with D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard (250 fmol), the samples were subjected to mild acid hydrolysis(70 °C, 1h), neutralized with NH4OH, and purified by SPE. O6-POB-G adducts remaining in DNA after repair reaction were quantified by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described above.

Second Order Kinetics for AGT Reactions with O6-POB-dG-Containing DNA

DNA duplexes containing site-specific O6-POB-G adducts (500 fmol, Table 1) were mixed with human recombinant AGT protein (400 fmol) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8) buffer containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and 0.5 mM DTT (final volume, 90 μl). Samples were incubated at room temperature for 0-50 seconds and quenched with acid (final concentration, 0.1N HCl). Following the addition of D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard (250 fmol), DNA was subjected to mild acid hydrolysis (1 h at 70 °C), and the unrepaired O6-POB-dG adducts remaining in DNA were quantified by capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described above.

Second order rates (k) for AGT repair of O6-POB-G were calculated by plotting O6-POB-G concentrations repaired at time t (average of 4 separate measurements) versus time and fitting the data to the 2nd order kinetic equation (Equation 1) using the KaleidaGraph software:25

| (1) |

where A0 is the concentration of AGT protein, B0 is the starting concentration of O6-POB-dG containing DNA, and Ct is the concentration of O6-POB-G repaired at time t. The error in the reaction rate measurements was obtained from KaleidaGraph software by approximating how closely the experimentally obtained data points fit the defined 2nd order kinetic equation.

Kinetics of POB Group Transfer to the AGT Protein

DNA duplexes (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′ (+) strand, 20 pmol) were dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM DTT. Following the addition of human recombinant AGT protein (16 pmol), the reaction mixtures (final volume, 90 μl) were incubated at room temperature for fixed periods of time (0 - 40 s). Each reaction was manually quenched by the addition of 0.5 N NaOH (90 μl). Samples were neutralized with HCl, dried under vacuum, and reconstituted in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.9, 50 μl). The protein was digested with trypsin (0.3 μg) for 18 hours at 37 °C.27 The resulting tryptic peptides were desalted using Millipore C18 Zip Tips (Bedford, MA) and dried under reduced pressure. Samples were re-suspended in 20 μl of 0.1% formic acid and analyzed by capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described below.

Capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analyses of tryptic peptides were performed with a Thermo-Finnigan Ultra TSQ mass spectrometer interfaced with a Waters Acquity capillary HPLC system. HPLC separation was achieved with a Zorbax 300 SB-C8 column (0.3 mm × 150 mm, 3.5 μm, Agilent Technologies) eluted at a flow rate of 6 μL/min and maintained at a temperature of 50 °C. HPLC solvents were aqueous 0.5% formic acid containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (A) and acetonitrile containing 0.5% formic acid and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (B). A linear gradient of 3% to 55% B in 15 minutes was followed by isocratic elution at 55% B for 10 minutes. Under these conditions, unmodified AGT peptide eluted at ~ 24.1 minutes, while pyridyloxobutylated peptide eluted within ~ 24.5 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ion mode with a spray voltage of 3.5 kV, a capillary temperature of 250 °C, and tube lens offset of 103 V. Nitrogen was used as a sheath gas (25 counts).

Quantitative analyses were conducted in the MS/MS mode with collision energy of 24 V. Argon was used as a collision gas at a pressure of 1.3 m Torr, and all analyses were performed with a scan width of 0.3 m/z and a scan time of 0.15 s. Unmodified AGT active site peptide (G136NPVPILIPCHR147) was detected in the SRM mode by monitoring the transition m/z 658.4 [M + 2H]+2 → m/z 948.6 [y8], while the corresponding pyridyloxobutylated peptide (G136NPVPILIP[C-POB]HR147) was detected using the MS/MS transition m/z 731.8 → m/z 1095.6 [y8] (Figure 6A, Supplement S-1). The percent pyridyloxobutylation of AGT Cys-145 residue was calculated from the HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS peak corresponding to the unmodified peptide containing the active site cysteine (Aunmodified) and the pyridyloxobutylated peptide (APOB) according to Equation 2:

| (2) |

and plotted against reaction time (t) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Formation of pyridyloxobutylated AGT protein following incubation with O6-POB-dG-containing DNA duplex (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′ and its compliment): Capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of pyridyloxobutylated AGT active site peptide (G136NPVPILIPCHR) (A). Time course for the formation of pyridyloxobutylated AGT protein (B). The line was generated by fitting the data to a single exponential equation using KaleidaGraph software.

Results

Stable Isotope labeling HPLC ESI+-MS/MS Approach

As discussed above, previous methodologies have relied on radioflow HPLC or gel electrophoresis of 32P endlabeled DNA oligomers to analyze the kinetics of O6-POB-dG repair by AGT.13,14 In the present work, a non-radioactive stable isotope labeling HPLC ESI+-MS/MS approach was developed to analyze the influence of DNA sequence context on the kinetics of O6-POB-G adduct repair by AGT. In our approach, synthetic DNA duplexes containing site specific O6-POB-dG adducts are incubated with human recombinant AGT protein (WT h-AGT) for specified periods of time, and the reactions are quenched with HCl (Figure 1).19 DNA is subjected to mild acid hydrolysis to release purines, including any O6-POB-G adducts remaining after the repair reaction, which are then quantified by isotope dilution - capillary HPLC electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Our initial studies (not shown) confirmed that no spontaneous removal of the POB group is observed under these conditions (0.1 N HCl, 70 °C, 1h). Quantitation is conducted in the selected reaction monitoring mode using the HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS peak areas corresponding to O6-POB-G and the deuterated internal standard (D4-O6-POB-G).

Figure 1.

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS methodology employed for quantitative analyses of O6-POB-G adducts remaining in DNA following AGT repair.

ESI+-MS/MS spectrum of O6-POB-G (m/z 229.0, [M + H]+) is characterized by two major fragment ions at m/z 148.1 [POB+] and m/z 152.1 [Gua + H]+ (Figure 2A). ESI+-MS/MS spectrum of D4-O6-POB-G (m/z 303.1 [M + H]+) contains one main prominent peak at m/z 152.1, corresponding to both [D4-POB+] and [Gua + H]+ (Figure 2B). Our quantitatifve method for O6-POB-G is based on selected reaction monitoring (SRM) of the transitions m/z 299.1 [M + H]+ → 148.1 [POB+], m/z 299.1 → [M + H]+ → 152.1 [Gua + H] +for O6-POB-G and m/z 303.1 [M + H] + → 152.1 [D4-POB+], m/z 303.1 [M + H] + → 152.1 [Gua + H] + for D4-O6-POB-G internal standard (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

ESI+-MS/MS spectra of O6-POB-G (A) and D4-O6-POB-G (B) and proposed structures of the major fragments.

Figure 3.

Capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of O6-POB-G adducts remaining in DNA following AGT repair reaction. 500 fmol of double-stranded DNA (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′ and its compliment) was incubated with 400 fmol of AGT protein for 20 seconds, followed by quenching with HCl and spiking with 250 fmol of D4-O6-POB-dG. The resulting mixture was subjected to acid hydrolysis and analyzed by capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS. The mass spectrometer was operated in SRM mode by monitoring the transitions m/z 299.09 [M + H+] →148.1 [POB+], 152.07 [Gua + H+] for O6-POB-G (A) and m/z 303.09 [M + H+]→152.07[D4-POB+], [Gua + H+] for D4-O6-POB-G (B).

HPLC separation is achieved with a capillary Zorbax SB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies) eluted at a flow rate of 15 μl/min with a gradient of 15 mM ammonium acetate and acetonitrile. Under our conditions, O6-POB-G standard and D4-O6-POB-G internal standard co-elute at ~ 14 min (Figure 3). Quantitative analyses were conducted by comparing the HPLC ESI+-MS/MS peak areas corresponding to O6-POB-G and D4-O6-POB-G internal standard. The lower limit of detection for O6-POB-G was estimated as 3 fmol, with a signal to noise ratio (S/N) of 3. The lower limit of quantification of O6-POB-G adducts by our HPLC ESI+-MS/MS method was estimated as 10 fmol with a signal to noise ratio of 5.

The new HPLC ESI+-MS/MS method was validated by performing the analyte recovery assay. Synthetic DNA duplex (5′-ACCCGCGTCCGCGCCA TGGCC-3′ and its compliment, 1pmol) was spiked with increasing amounts of the corresponding O6-POB-dG-containing duplex (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCA TGGCC-3′ and its compliment, 0.1-1pmol) and acid-inactivated recombinant AGT protein (WT h-AGT, 400 fmol). The resulting mixtures were subjected to mild acid hydrolysis, followed by sample processing and capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis as described above. The observed O6-POB-G/ D4-O6-POB-G ratios were plotted against the theoretical ratios of O6-POB-G/ D4-O6-POB-G (Figure 4). A linear correlation with an R2 value of 0.9965 and a slope of 1.0254 was obtained, validating our quantitative HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS method for O6-POB-G adducts in DNA.

Figure 4.

Validation results for quantitative capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS method for O6-pobG using isotope dilution with D4-O6-POB-G internal standard. Synthetic O6-pob-dG-containing DNA duplex (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′ and its compliment, 0.1-1pmol) was mixed with the corresponding native DNA duplex (1 pmol), D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard, and acid-inactivated AGT protein (500 fmol)(N=4). The resulting mixtures were subjected to mild acid hydrolysis, and O6-POB-G adducts were quantified by capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS. The results are expressed as a ratio of HPLC-ESI-MS/MS peak areas corresponding to O6-POB-G and D4-O6-POB-G versus the actual O6-POB-G|D4-O6-POB-G molar ratio.

Time Course of AGT Repair within p53 codon 158 Derived DNA Sequences

To test the applicability of our analytical methodology to studies of AGT repair kinetics, time dependent repair of O6-POB-dG in the presence of increasing amounts of human recombinant AGT protein was investigated. Synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide duplexes representing codon 158 of the p53 tumor suppressor gene and surrounding sequence were prepared containing O6-POB-dG adduct at the second position of p53 codon 158 (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′, (+) strand). Following annealing to the complementary strand, the resulting site-specifically modified duplexes were incubated with 0.1-1.6 equivalents of human recombinant AGT protein over fixed periods of time (0-600 s), and O6-POB-dG adducts remaining in DNA were quantified by HPLC ESI+-MS/MS.

The repair ratios for the control samples (R0) consisted of peak area of O6-POB-G/ D4-O6-POB-G in DNA alone (time t = 0 sec), while repair ratios at time = t (Rt) was obtained by analyzing ratios of area of O6-POB-G/ D4-O6-POB-G upon incubation of DNA with AGT protein for a given time (Equation 3). The percent repair (% repair) of O6-POB-dG was obtained by calculating the difference in repair of control samples and repaired DNA at a given time followed by dividing this value by the repair ratio of the control sample times 100% (Equation 3).25

| (3) |

A plot of % repair versus time revealed a time- and concentration-dependent removal of O6-POB-dG adducts by AGT (Figure 5). As expected for second order kinetics, increased AGT concentrations resulted in a proportional increase in the rate of O6-POB-G repair. The extent of DNA dealkylation increased proportionately until ~ 60 s, after which no additional repair was observed for the remainder of the incubation due to the depletion of active AGT protein as a result of alkyl group transfer to Cys-145 (Scheme 1). We have previously observed similar results for AGT-mediated repair of O6-methyl-dG adducts.19

Figure 5.

Time course for the repair of O6-POB-G adducts incorporated into synthetic DNA duplexes (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′ and its compliment) in the presence of increasing amounts of recombinant human AGT protein (20, 200, 400, or 800 fmol). O6-POB-G adducts remaining in DNA following the specified reaction times were quantified by isotope dilution HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS. The line was generated by fitting to a single-exponential equation using KaleidaGraph software.

Mass Spectrometry-based Detection of Pyridyloxobutylated AGT Protein

As discussed above, AGT repair reaction involves alkyl group transfer from DNA to an active site cysteine of the protein (Cys-145 in human AGT).7 To investigate the kinetics of protein pyridyloxobutylation in the presence of O6-POB-dG-containing DNA, AGT repair reactions with p53 codon 158 containing DNA duplexes (5′-ACCCGCGTCC[O6-POB-G]CGCCATGGCC-3′+ complement) were quenched with NaOH, and the time-dependent formation of alkylated protein was followed by capillary HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of the tryptic peptide G136NPVPILIPC145HR147 corresponding to AGT active site containing cysteine 145 (Cys-145). Both intact (M = 1314.4 Da) and pyridyloxobutylated AGT active site peptide (M = 1461.6 Da, POB group = 147 Da) were detected using selected reaction monitoring of the y8 fragment formation from doubly charged pseudo-molecular ions of the peptides of interest (m/z 658.2→ 948.6 for unmodified peptide and m/z 731.8 →1095.6 for pyridyloxobutylated peptide; see Figure 6A). HPLC-ESI-MS/MS peak areas corresponding to the intact and alkylated peptide were compared to calculate the extent of protein pyridyloxobutylation. A time-dependent increase in the concentration of pyridyloxobutylated protein was observed until ~ 15 seconds, after which the concentrations of pyridyloxobutylated protein formed leveled off due to the depletion of active protein (Figure 6B). The reaction rate was faster than that in the experiments shown in Figure 5 due to the increased concentrations of DNA substrate and AGT protein used in this experiment. Higher protein amounts were required to facilitate the detection of pyridyloxobutylated active site peptide.

Kinetics of AGT Repair of O6-POB-G Adducts within DNA Sequence Representing codon 12 of the rat H-ras Gene

The new HPLC-ESI-MS/MS methodology was employed to analyze the kinetics of AGT-mediated POB transfer from O6-POB-dG-containing DNA duplexes derived from rat H-ras gene as a function of the partner base in the opposite strand. Synthetic DNA duplexes (5′-AATAGTATCT[O6-POB-G]GAGCC-3′, where O6-POB-G is placed at the first position of H-ras codon 12 were prepared containing either C or T opposite O6-POB-G. Following incubation of adducted duplexes with recombinant human AGT protein for defined periods of time, the reactions were quenched with acid, spiked with D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard, and the amounts of O6-POB-G adducts remaining in DNA were determined by isotope dilution capillary HPLC ESI+-MS/MS. This was used to calculate the amounts of O6-POB-G adducts removed at time t (Figure 7). A graph of O6-POB-G concentrations repaired versus time was obtained, and the resulting curves were fitted to the 2nd order kinetics equation (Equation 4) using KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software, Reading, PA)25,28:

| (4) |

where A0 is the molar concentration of AGT protein, B0 is the molar concentration of O6-POB-G containing DNA duplex, Ct is the concentration of O6-POB-G adducts repaired at time t, t is the time in seconds, and k is the 2nd order rate for O6-POB-G repair.

Figure 7.

AGT repair kinetics for O6-POB-dG adducts placed opposite dC or dT in synthetic DNA duplexes (5′-AATAGTATCT[O6-POB-G]GAGCC-3′ + strand) containing either C or T opposite the adducts). DNA (500 fmol) was incubated with human recombinant AGT protein (400 fmol) for increasing lengths of time (0-50 seconds). The reactions were stopped by HCl quenching, and unrepaired O6-POB-G adducts were quantified by isotope dilution HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS. Each data point represents an average of four independent measurements. The curves represent the best fit to a second-order exponential equation that provides the rate of O6-POB-dG repair by AGT obtained by the KaleidaGraph software. The error is estimated by determining how closely the second order kinetic equation fits the actual data points.

Kinetic analysis have yielded the 2nd order rates of 1.17 ± 0.05 × 106 M−1s−1 for repair of O6-POB-G paired with C and 1.74 ± 0.1 × 106 M−1S−1 for O6-POB-G mispaired with T (Figure 7).

Discussion

The presence of functional AGT protein is crucial for cellular protection against alkylating agents such as nitrosamines present in tobacco smoke.3,4 If not repaired, O6-alkylguanines can pair with a T or A instead of C during DNA replication, leading to G → A transitions and G → T transversion mutations.5 Human cancers with reduced expression levels of the AGT protein have an increased frequency of G → A mutations in the K-ras protooncogene and the p53 tumor suppressor gene as compared to tumors with normal expression of AGT,29-32 indicative of a major protective function of AGT protein against these genetic changes. Epigenetic silencing of the MGMT gene coding for AGT has been correlated with susceptibility for tumor development following exposure to alkylating agents.33

Previous studies have revealed that the efficiency of AGT-mediated repair of O6-alkylguanines is affected by adduct structure, local sequence context, and the identity of the base in the opposite strand.34 The relative rates of AGT-mediated repair of O6-alkyl-dG lesions have been reported as benzyl > methyl > ethyl >> 2-hydroxyethyl >4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobutyl, probably due to a slower rate of transfer of bulky alkyl groups to the active site cysteine when they are bound in an inactive conformation.14,34

AGT repair involves several distinct kinetic steps that have different rates.28 Following binding to the minor groove of DNA, AGT protein flips the adducted nucleotide out of the DNA base stack to enter the protein active site pocket, while Arg128 takes the place of the adducted nucleotide in the DNA duplex.6,9 The alkyl group is then transferred from the O6-position of guanine to the active site cysteine of AGT via an in-line displacement reaction, and finally, the alkylated AGT dissociates from the repaired DNA. The rate of AGT binding to DNA appears to be diffusion-limited (5 × 109 M−1 s−1) and is unaffected by the identity of the alkyl group on the O6-alkyl-dG lesion or the nucleotide sequence surrounding the lesion,14 while the rate of protein dissociation is slower.28 The rate of AGT-mediated nucleotide flipping is between 80 and 200 s−1 25 and is equally efficient for methyl and benzyl adducts.28 The alkyl transfer step appears to be rate limiting for O6-Me-dG and O6-POB-dG adducts, although the rates of alkyl transfer have not been measured directly, but calculated from the rates for all of the other steps in the reaction.28

In our earlier work, we have developed a quantitative HPLC ESI+-MS/MS methodology for analyzing the kinetics of AGT-mediated repair of O6-methyl-dG adducts in vitro.19,25 Our analyses have employed second-order kinetics, as explained by a simple bimolecular reaction between the AGT protein and its DNA substrate (Scheme 1). Under these conditions, AGT repair of O6-methyl-dG exhibited a moderate sequence dependence, with ~2-fold differences between the rate of repair of O6-Me-dG located at the first and the second position of human K-ras codon 12.19 The dealkylation rate was weakly influenced by the methylation status of neighboring cytosine bases due to its effects on the rate of alkyl transfer.25 While the overall effects of sequence context on O6-Me-dG repair by AGT were modest, due to the stochiometric nature of AGT reaction, even small differences in substrate preference may influence the probability of lesion repair at specific sites within the genome.8

In comparison to O6-Me-dG, AGT-mediated repair of bulky alkylguanine adducts such as O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]deoxyguanosine (O6-POB-dG) appears to be more strongly affected by the local DNA sequence context.13,14 As discussed above, O6-POB-dG is an important DNA lesion induced by tobacco-specific nitrosamines NNK and NNN and playing an important role in the carcinogenic mechanism of NNK.4,5 In general, AGT repair of O6-POB-dG is less efficient than that of O6-Me-dG, probably due to the larger adduct size and the possibility of adduct binding to AGT active site in a non-reactive conformation.14 Coulter et al. and Mijal et al. previously reported that the first order rate for AGT repair of O6-POB-dG placed at the first guanine of H-ras codon 12 was greater as compared to adducts present at the second G.13,14 However, to our knowledge, there has been no systematic study of the effects of DNA sequence on AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG lesions.

In the present work, a non-radioactive, sensitive, and accurate isotope dilution HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS methodology was developed to analyze the kinetics of O6-POB-dG adduct repair by AGT. In our approach, DNA duplexes containing site-specific DNA adducts are incubated with recombinant human AGT protein for fixed periods of time, followed by acid hydrolysis and HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of O6-POB-G adducts remaining in DNA over time. Since no separation of alkylated and dealkylated strands is required, this methodology is highly reliable and is applicable to AGT repair studies with DNA of any sequence and length.

The applicability of the new method was demonstrated by analyzing the kinetics of AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG lesions placed within the context of p53 codon 158 in the presence of increasing AGT amounts (Figure 5). As expected, the rate of O6-POB-dG repair increased proportionally as the AGT amounts were raised. Saturation of repair was observed when using low AGT:DNA ratios due to the depletion of active protein. As was the case with O6-Me-dG,19 we did not observe quantitative repair of O6-POB-dG lesions even when using 1.6 molar excess protein under these in vitro conditions, which could be a result of cooperative AGT-DNA binding10 and/or the competition of active protein with alkylated protein for binding to the DNA substrate.8

Second order rates of AGT-mediated repair of O6-POB-dG placed at the first position of rat H-ras codon 12 were determined with cytosine or thymine opposite the adduct. We found that the rate of AGT repair was 1.5 fold faster for the O6-POB-dG:T base pair than for the O6-POB-dG:C pair (1.74 ± 0.1 × 106 M−1s−1 versus 1.17 ± 0.05 × 106 M−1s−1) (Figure 7). This observation is consistent with an earlier report by Mijal et al.,13 who demonstrated that placing a thymine opposite a O6-POB-dG adduct caused an increase in AGT mediated repair as compared to O6-POB-dG:C base pair. By comparison, the rates of AGT-mediated repair of O6-Me-dG:C placed in a similar sequence context (K-ras codon 12) are 5-10 times greater (7.4 -14 × 106 M−1s−1).19,34 Our ongoing investigations (not shown) suggest that this difference in repair rates is due to a combination of slower nucleotide flipping and alkyl transfer steps in the case of bulky O6-POB-dG adducts.

In conclusion, an accurate and general isotope dilution capillary HPLC ESI+-MS/MS method has been developed to investigate the rates of AGT mediated repair of O6-POB-dG adducts as a function of local DNA sequence. This methodology will be useful for future investigations of the kinetics of AGT-mediated repair of pyridyloxobutylated DNA adducts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Stephen S. Hecht (University of Minnesota Cancer Center) for D4-O6-POB-dG internal standard and Dr. Lisa Peterson (University of Minnesota Cancer Center) for O6-POB-dG-containing oligomer derived from the rat H-ras gene. We are grateful to Brock Matter and Dr. Peter Villalta (Analytical Biochemistry and Mass Spectrometry Facility at the Cancer Center, University of Minnesota) for their assistance with mass spectrometry analyses and Robert Carlson (University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center) for preparing figures for this manuscript.

Funding Support This work was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-095039).

Footnotes

Abbreviations AGT, O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase; BSA, bovine serum albumin; O6-Bz-dG, O6-benzyl-deoxyguanosine; CID, collision induced dissociation; DTT, dithiothreitol; DNase I, deoxyribonuclease I; ESI-MS/MS, electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry; EDTA, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid; HPLC-ESI-MS/MS, high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization with time of flight detection; N7-MeG, N7-methylguanine; O6-Me-dG, O6-methyl-2′-deoxyguanosine; O6-Me-G, O6-methylguanine; N7-POB-G, N7-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)-but-1-yl]guanine; NNK, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone; O6-POB-dG, O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]deoxyguanosine; D4-O6-POB-dG, D4-O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]deoxyguanosine; O6-POB-G, O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]guanine; PDE I, phosphodiesterase I; PDE II, phosphodiesterase II; POB, pyridyloxobutyl; SPE, solid phase extraction; SRM, selected reaction monitoring; TSQ, triple stage quadrupole.

Reference List

- 1.Hecht SS, Chen CB, Ohmori T, Hoffmann D. Comparative carcinogenicity in F344 rats of the tobacco-specific nitrosamines, N’-nitrosonornicotine and 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Cancer Res. 1980;40:298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hecht SS, Morse MA, Amin S, Stoner GD, Jordan KG, Choi CI, Chung FL. Rapid single-dose model for lung tumor induction in A/J mice by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and the effect of diet. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:1901–1904. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.10.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hecht SS. Biochemistry, biology, and carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998;11:559–603. doi: 10.1021/tx980005y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht SS. DNA adduct formation from tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Mutat. Res. 1999;424:127–142. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauly GT, Peterson LA, Moschel RC. Mutagenesis by O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine in Esherichia coli and human cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:165–169. doi: 10.1021/tx0101245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels DS, Woo TT, Luu KX, Noll DM, Clarke ND, Pegg AE, Tainer JA. DNA binding and nucleotide flipping by the human DNA repair protein AGT. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:714–720. doi: 10.1038/nsmb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pegg AE. Repair of O6-alkylguanine by alkyltransferases. Mutat. Res. 2000;462:83–100. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pegg AE. Multifaceted roles of alkyltransferase and related proteins in DNA repair, DNA damage, resistance to chemotherapy, and research tools. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:618–639. doi: 10.1021/tx200031q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tubbs JL, Pegg AE, Tainer JA. DNA binding, nucleotide flipping, and the helix-turn-helix motif in base repair by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and its implications for cancer chemotherapy. DNA Repair. 2007;6:1100–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried MG, Kanugula S, Bromberg JL, Pegg AE. DNA Binding mechanism of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: Stoichiometry and effects of DNA base composition and secondary structure on complex stability. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15295–15301. doi: 10.1021/bi960971k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Major GN, Brady M, Notarianni GB, Collier JD, Douglas MS. Evidence for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the DNA repair enzyme for O6-methylguanine in non-tumour derived human cell and tissue extracts. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1997;25:359S. doi: 10.1042/bst025359s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouws C, Pretorius PJ. O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT): Can function explain a suicidal mechanism? Med. Hypotheses. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mijal RS, Kanugula S, Vu CC, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Peterson LA. DNA Sequence context affects repair of the tobacco-specific adduct O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine by human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4968–4974. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulter R, Blandino M, Tomlinson JM, Pauly GT, Krajewska M, Moschel RC, Peterson LA, Pegg AE, Spratt TE. Differences in the rate of repair of O6-alkylguanines in different sequence contexts by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007;20:1966–1971. doi: 10.1021/tx700271j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Spratt TE, Liu XK, Hecht SS, Pegg AE, Peterson LA. Pyridyloxobutyl adduct O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine is present in 4-(acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-treated DNA and is a substrate for O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:562–567. doi: 10.1021/tx9602067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gait MJ. Oligonucleotide synthesis: a practical approach. IRL Press; Washington, DC: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edara S, Kanugula S, Goodtzova K, Pegg AE. Resistance of the human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase containing arginine at codon 160 to inactivation by O6-benzylguanine. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5571–5575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Xu-Welliver M, Kanugula S, Pegg AE. Inactivation and degradation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase after reaction with nitric oxide. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3037–3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guza R, Rajesh M, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Tretyakova N. Kinetics of O6-Me-dG repair by O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase within K-ras gene derived DNA sequences. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006;19:531–538. doi: 10.1021/tx050348d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Spratt TE, Pegg AE, Peterson LA. Synthesis of DNA oligonucleotides containing site-specifically incorporated O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine and their reaction with O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12:127–131. doi: 10.1021/tx980251+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matter B, Wang G, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Formation of diastereomeric benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-guanine adducts in p53 gene-derived DNA sequences. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004;17:731–741. doi: 10.1021/tx049974l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziegel R, Shallop A, Upadhyaya P, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Endogenous 5-methylcytosine protects neighboring guanines from N7 and O6-methylation and O6-pyridyloxobutylation by the tobacco carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Biochemistry. 2004;43:540–549. doi: 10.1021/bi035259j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tretyakova N, Matter B, Jones R, Shallop A. Formation of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-DNA adducts at specific guanines within K-ras and p53 gene sequences: stable isotope-labeling mass spectrometry approach. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9535–9544. doi: 10.1021/bi025540i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziegel R, Shallop A, Jones R, Tretyakova N. K-ras gene sequence effects on the formation of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK)-DNA adducts. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003;16:541–550. doi: 10.1021/tx025619o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guza R, Ma L, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Tretyakova N. Cytosine methylation effects on the repair of O6-methylguanines within CG dinucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22601–22610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajesh M, Wang G, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Stable isotope labeling-mass spectrometry analysis of methyl- and pyridyloxobutyl-guanine adducts of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in p53-derived DNA sequences. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2197–2207. doi: 10.1021/bi0480032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeber R, Rajesh M, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Tretyakova N. Cross-linking of the human DNA repair protein O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase to DNA in the presence of 1,2,3,4-diepoxybutane. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006;19:645–654. doi: 10.1021/tx0600088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zang H, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Guengerich FP. Kinetic analysis of steps in the repair of damaged DNA by human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30873–30881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf P, Hu YC, Doffek K, Sidransky D, Ahrendt SA. O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase promoter hypermethylation shifts the p53 mutational spectrum in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8113–8117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esteller M, Toyota M, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Capella G, Peinado MA, Watkins DN, Issa JP, Sidransky D, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Inactivation of the DNA repair gene O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation is associated with G to A mutations in K-ras in colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2368–2371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bello MJ, Alonso ME, Aminoso C, Anselmo NP, Arjona D, Gonzalez-Gomez P, Lopez-Marin I, de Campos JM, Gutierrez M, Isla A, Kusak ME, Lassaletta L, Sarasa JL, Vaquero J, Casartelli C, Rey JA. Hypermethylation of the DNA repair gene MGMT: association with TP53 G:C to A:T transitions in a series of 469 nervous system tumors. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2004;554:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura M, Watanabe T, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Promoter methylation of the DNA repair gene MGMT in astrocytomas is frequently associated with G:C −> A:T mutations of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1715–1719. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.10.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirtz S, Nagel G, Eshkind L, Neurath MF, Samson LD, Kaina B. Both base excision repair and O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase protect against methylation-induced colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:2111–2117. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guza R, Pegg AE, Tretyakova N. Effects of sequence context on O6-alkyltransferase repair of O6-alkyldeoxyguanosine adducts. ACS Symposium Series. 2010;1041:73–101. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.