Abstract

An immuno-inhibitory role of B7-H1 expressed by non-T cells has been established, however, the function of B7-H1 expressed by T cells is not clear. Peak expression of B7-H1 on antigen-primed CD8 T cells was observed during the contraction phase of an immune response. Unexpectedly, B7-H1 blockade at this stage reduced the numbers of effector CD8 T cells, suggesting B7-H1 blocking antibody may disturb an unknown function of B7-H1 expressed by CD8 T cells. To exclusively examine the role of B7-H1 expressed by T cells, we introduced B7-H1 deficiency into TCR transgenic (OT-1) mice. Naive B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells proliferated normally following antigen stimulation, however once activated, they underwent more robust contraction in vivo and more apoptosis in vitro. In addition, B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells were more sensitive to Ca-dependent and Fas ligand-dependent killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Activation-induced Bcl-xL expression was lower in activated B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells, while Bcl-2 and Bim expression were comparable to the wild type. Transfer of effector B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells failed to suppress tumor growth in vivo. Thus, up-regulation of B7-H1 on primed T cells helps effector T cells survive the contraction phase and consequently generate optimal protective immunity.

INTRODUCTION

B7-H1 is an immuno-regulatory molecule in the B7 family. We first described B7-H1 in 1998 (1) and identified its expression in human cancer cells in 2002 (2). Since then, B7-H1 has been reported to be aberrantly expressed by many human cancer cells and high B7-H1 expression has been correlated with poor prognosis in several human cancers (3). Thus, B7-H1 blockade has been proposed as a means of countering the immunosuppressive effects of tumors to improve tumor immunotherapy (4–7). However, the drive to exploit B7-H1 as a clinical immune target has outpaced any comprehensive understanding of B7-H1 function.

B7-H1 is expressed by several cell types, including T cells. Its constitutive expression is primarily restricted to cells of myeloid- lineage such as macrophages and dendritic cells in both mice and humans (1, 2, 8). In other cell types such as lymphoid -lineage cells, endothelial and epithelial cells, B7-H1 expression can be either induced or up-regulated by IFN-γ and TNF-α (7). Naïve murine T cells constitutively express low levels of B7-H1, whereas naïve human T cells do not, and both murine and human T cells express markedly increased levels of B7-H1 after activation (1, 8, 9). In contrast to accumulating studies on tumor B7-H1, less attention has been paid to elucidating the functional role of B7-H1 expressed by T cells, especially in modulation of protective T cell immunity. Given that T cells are major immune effectors and that B7-H1 has a dynamic expression on activated T cells, it is imperative to address the functional role of T cell-associated B7-H1 in greater detail.

B7-H1 expressed by non-T cells (macrophages, tumor cells) functions as a negative regulator of T cell responses (7). Therefore, B7-H1 blockade strategy has been used to improve immune responses against tumors and various infections (7). However, some deleterious effects of B7-H1 blockade have been reported in animal models of infection (10, 11) and inflammation (12). Pathogen-specific effector T cells have been found to express higher levels of B7-H1, and B7-H1 deficiency has been shown to impair the development and maintenance of effector T cells (13). Common features of studies using infection or inflammation models include the up-regulation of B7-H1 on effector T cells during the acute phases of the immune reaction and subsequent reduction and contraction of the effector T cell populations, as well as compromised protective immunity after B7-H1 antibody treatment. Despite these unexpected observations, the detailed function of B7-H1 expressed by T cells in antigen-specific, notable anti-tumor T cell responses has not been addressed.

The present study was designed to directly examine the role of B7-H1 expressed by antigen-specific T cells in regulation of T cell function and survival. We found that B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells, while undergoing normal antigen-initiated expansion, exhibited increased contraction in vivo and more apoptosis after antigen- stimulation in vitro. B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells also show increased susceptibility to killing by other CTLs. In addition, we observed that in response to activation, B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells expressed lower levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL, whereas expressions of two other key mediators of intrinsic apoptotic pathway, Bcl-2 and Bim, remained comparable to wild type. Taken together, our studies suggest a pro-survival function of B7-H1 that is essential for effector T cells to survive during contraction phase of the immune response thereby eliciting protective immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, cell lines and reagents

Female C57BL/6 mice and B6.SJL congenic mice (8–12 weeks old) were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and NIH. OT-1 TCR (Thy 1.2 ) transgenic mice and Thy1.1+ B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MA). OT-1 Thy1.1 mice were provided by Dr. Tian Tian (Harvard University). B7-H1 KO B6 mice (14) were used to breed B7-H1 KO OT-1 TCR transgenic mice. Murine melanoma cells (B16-OVA), EG7-OVA and EL4 thymoma cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro, Hendon, VA) with 10% FBS (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), 1U/mL penicillin, 1 μg/mL streptomycin, and 20 mM Hepes buffer (all from Mediatech, Manassas, VA). Studies were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the proper use of animals in research and with local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval.

Flow cytometry analysis

Class I MHC (KbOVA peptide SIINFEKL) tetramer and negative control tetramer were purchased from Beckman Coulter (Brea, CA). Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD8, CD44, CD62L, CCR7, CD43 (1B11), Fas (CD95), Fas ligand, CD122, CD127, CD45.2 (Ly 5.2), and CD90.2 (Thy1.2) were purchased from BD Biosciences (Mountain View, CA), BioLegend (San Diego, CA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Antibodies to Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and Bim and fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). To detect the intracellular levels of Bcl-xl, Bcl-2 and Bim, T cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C followed by permeabilization with ice-cold methanol for 30 min. After blocking with 15% rat serum for 15 min, cells were stained with antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After staining, cells were washed three times with incubation buffer before analysis. At least 100,000 viable cells were live-gated on FACScan or FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) instrumentation. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

T cell immunization, activation and apoptosis assay

To induce in vivo CD8 T cell responses, mice were immunized with intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mg of OVA protein (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 50 μg poly (I:C) (Sigma-Aldrich) as reported (15). For in vitro T cell activation and apoptosis assay, purified CD8 T cells were labeled with CFDA-SE (Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester) (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and incubated with OVA peptide 257–264 at 0.2 μg/ml for 72 h. Proliferation of T cells was analyzed by CFSE dilution using flow cytometry. Apoptosis of CD8 T cells was analyzed by staining using Annexin V antibody (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and TMRE (Tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester) (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Apoptosis in orogress was analyzed by intracellular staining for active caspase-3 using antibody from BD Biosciences (clone C92–605, Mountain View, CA).

Adoptive transfer of effector CD8 T cells in tumor models

Purified CD8 T cells were activated for 24–48 h with anti-CD3/CD28 beads or OVA peptide and IL-2 (Chiron, Emeryville, CA)(10 IU/ml) and transferred into sublethally-irradiated B6 mice. For tumor suppression assays, mice were injected with B16-OVA tumors (5×105, s.c. in the right flank) one day after T cell transfer. Tumor growth was monitored by measurement of the longest bisecting diameters of flank tumors. For tumor infiltrating assays, EG7-OVA tumor cells (1×106) were injected i.p. on day 7 after T cell transfer. One week after tumor cell injection, cells from peritoneal cavities were harvested for flow cytometry assay.

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) function assay

Degranulation of CTLs was analyzed by CD107a mobilization (16) followed by intracellular staining for IFN-γ. To detect cytotoxicity, target cells were labeled with calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes) before the CTL assay (17). Calcein release, quantified by an automated fluorescence measurement system with an excitation of 485/20 and an emission filter of 530/25 scanning for 1 sec per well, was used to measure target cell lysis. Antigen-specific cytotoxic activity was calculated as % specific lysis = 100 × [(test release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release)].

T cell-T cell fratricide assay

Effector CTLs were prepared by activating CD8 T cells from OT-1 mice for 48 h in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 or antigen peptide and IL-2 (10 IU/ml). Target T cells from WT or B7-H1 KO B6 mice were activated with Con A (5 μg/ml) for 48 h and loaded with or without OVA peptide followed by labeling with CFSE (1 μM). To block Ca-dependent or Fas ligand-mediated cytolytic activity, graded EGTA (Sigma) or 10 μg/ml of anti-Fas ligand neutralizing antibody (Clone MFL4, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) were added at the beginning of culture. The survival of CFSE+ target cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cytolytic activity was calculated as % lysis = (1- % CFSE+ of target with OVA peptide/% CFSE+ of target without peptide) × 100%.

Statistical analysis

A two-sided, unpaired Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical differences in tumor growth between groups of mice. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Late blockade of B7-H1 reduces the numbers of effector CD8 T cells following immunization

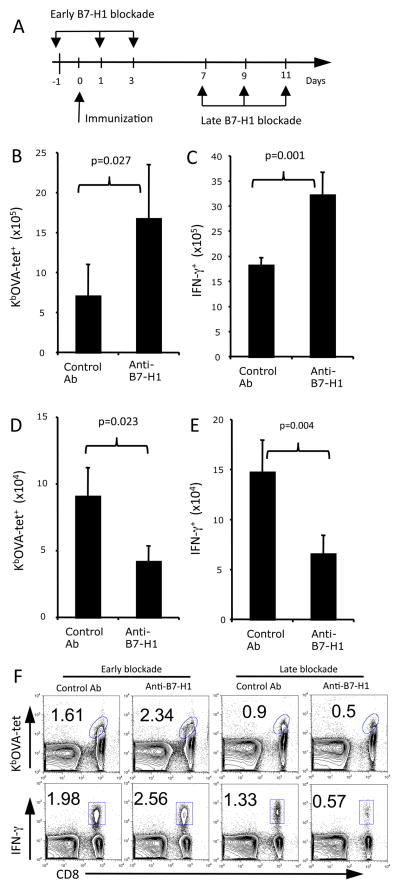

In our attempt to identify the optimal timing of B7-H1 blockade to improve T cell responses, we administrated anti-B7-H1 blocking antibody either during the early (days 0–3) or late (days 7–10) stages following immunization (Fig. 1A). These time periods were set according to the kinetics of T cell response following ovalbumin (OVA) and poly (I:C) immunization (15). Early B7-H1 blockade greatly increased the expansion of OVA antigen-specific (KbOVA tetramer+) and functional IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells in spleens of immunized mice (Fig. 1B-C and F, p<0.05, p<0.01). Unexpectedly, late B7-H1 blockade decreased the percentages and numbers of antigen specific (tetramer+) and effector (IFN-γ+) CD8 T cells in the spleens of mice (Fig. 1D–E and F, p<0.05; p<0.01). Taken together, the results of early blockade of B7-H1 are consistent with our and others’ reports suggesting an inhibitory role of B7-H1 expressed by antigen presenting cells (dendritic cells) during the early stage of T cell priming (18, 19). However, the opposite effects of late B7-H1 blockade indicate an unknown function of B7-H1 expressed by other cells than dendritic cells during the late stage of T cell responses.

Figure 1. Late B7-H1 blockade reduces the numbers of effector CD8 T cells following immunization.

C57BL/6 mice were injected with naïve OT-1 CD8 T cells (5×106, i.v.) and one day later were immunized with OVA protein/polyI:C. (A) Scheme of early vs. late B7-H1 blockade. Anti-B7-H1 mAb (10B5 or control IgG, 200 μg) was injected i.p. at indicated days. The spleen cells were isolated 7 days after last injection of antibodies and analyzed for KbOVA tetramer (tet) binding and intracellular IFN-γ production. (B–E) Bar graphs show the average numbers of tetramer+ and IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells in the spleens (mean ± SD, three mice/group) after early (B–C) and late (D–E) B7-H1 blockade. (F) Flow cytometry plots of tetramer+ and IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells after early and late B7-H1 blockade. One representative result of three independent experiments is shown. Numbers are percents of gated areas.

Effector CD8 T cells up-regulate B7-H1 following immunization

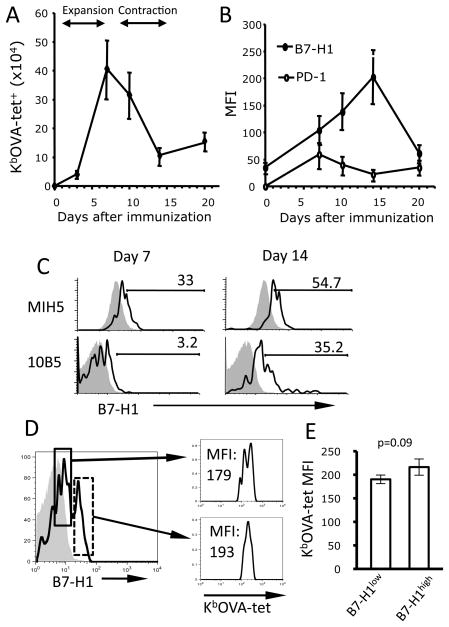

The observed difference in functionality of B7-H1 blockade depending on timing could reflect different role of B7-H1 associated with specific cell type expressing it. It has been reported that T cell activation leads to up-regulation of B7-H1 on both human and mouse T cells (8, 9). To determine whether B7-H1 expressed by activated T cells could be a potential target of late B7-H1 blockade, we examined the kinetics of B7-H1 expression on antigen specific CD8 T cells following immunization (15). As shown in Fig. 2A, number of antigen-specific (tetramer+) CD8 T cells rapidly increased between days 1–7 after immunization (expansion phase), gradually declined between days 7–14 (contraction phase) and remained stable thereafter. The levels of B7-H1, as represented by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), gradually increased on antigen-specific CD8 T cells, peaking on day 14, and declined to baseline level on day 20 (Fig. 2B). Peak expression of B7-H1 on antigen-specific CD8 T cells was verified on day 14 using a different anti-B7-H1 antibody (10B5), which only binds to B7-H1 expressed by activated T cells (20) (Fig. 2C). Even though two peaks of B7-H1 expression on activated T cells were noticed during days 10–14, this difference did not correspond to the different levels of OVA-tetramer staining (Fig. 2D–E, p=0.09). In contrast to B7-H1 expression, PD-1 expression peaked at day 7 and was maintained at low levels up to 20 days post- immunization. The uncoupled B7-H1 and PD-1 expression by CD8 T cells suggests that T cell-associated PD-1 and B7-H1 may have different regulatory functions at different stage of T cell responses.

Figure 2. Kinetics of B7-H1 expression on antigen-specific CD8 T cells following immunization.

C57BL/6 mice were immunized with OVA protein and poly (I:C). Antigen specific CD8 T cells in the spleen and their expression of B7-H1 and PD-1 were identified by co-staining with anti-CD8 and KbOVA-tetramer (tet) and anti-B7-H1 (MIH5) or anti-PD-1 (RMP 1–14) antibodies. (A, B) Data show the average tetramer+ cell numbers or MFI (mean of fluorescence intensity) of B7-H1 or PD-1 (mean ± SD, n=3). One of three independent experiments is shown. (C) B7-H1 expression on naive (shade lines) or activated (open lines) CD8 T cells was identified by two anti-B7-H1 antibodies (MIH5 or 10B5) on days 7 and 14 following immunization. Numbers indicate percentage of B7-H1 positive activated T cells above the base lines of their naïve counterparts. (D) B7-H1high (solid line) and B7-H1low (dashed line) cells show similar binding affinity in their KbOVA-tetramer staining. Shaded line is isotype control. (E) Bar graphs show the averages of MFI of KbOVA-tetramer staining for two B7-H1 populations from three samples.

B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells have normal initial proliferation but cannot accumulate due to increased apoptosis

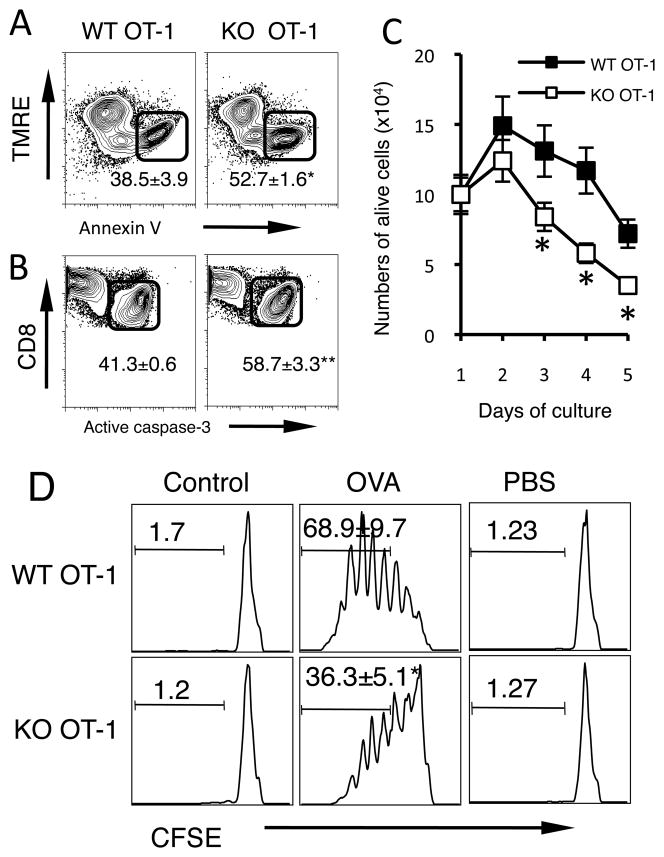

To directly indentify the function of B7-H1 expressed by CD8 T cells, we introduced B7-H1 deficiency into OT-1 TCR transgenic mice and produced B7-H1 deficient OT-1 mice in which CD8 T cells carry OVA-specific TCR but do not express B7-H1. We first examined their proliferation to antigen stimulation in vitro and in vivo. Naive B7-H1 KO and WT CD8 OT-1 T cells underwent similar antigen-stimulated proliferation in vitro and homeostatic proliferation in vivo (Supplemental Fig. 1 A and B). Next, we examined whether they have any difference in spontaneous apoptosis. Freshly isolated WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells underwent comparably low levels of spontaneous apoptosis demonstrated by similar levels of Annexin V binding, TMRE staining (measuring mitochondrial trans-membrane potential, which decreases during apoptosis) (21), and active caspase-3 levels (Supplemental Fig. 1C and D). Comparable rates of apoptosis of WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells were observed up to three days of culture in medium alone (Supplemental Fig. 1E), however, when stimulated with antigen (OVA), B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells underwent more apoptosis than WT CD8 T cells as demonstrated with annexin V+ and TMRElow staining (Fig. 3A, p<0.01) and increased levels of active caspase-3 (Fig. 3B, p<0.01). Accordingly, the numbers of alive B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells had ~2-fold decrease between days 3–5 after activation (Fig. 3C, p<0.05). To examine whether increased death of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells was due to impaired proliferation, CD8 T cells were labeled with CFSE (a intracellular dye for tracking cell division). On day 3 post antigen stimulation, B7-H1 KO and WT OT-1 CD8 T cells underwent similar proliferation (up to 6 divisions), but the percentage of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells that underwent 3 or more divisions decreased by ~2-fold compared to WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 3D, p<0.05). These results suggest the B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells undergo normal initial proliferation but cannot accumulate due to increased apoptosis.

Figure 3. Increased apoptosis of B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells following antigen stimulation.

Purified CD8 T cells from WT and B7-H1 KO OT-1 mice were incubated (1×106 cells/ml) with OVA-peptide (1 μg/ml) for up to 5 days in vitro. Apoptosis of antigen-stimulated CD8 T cells was analyzed by staining with TMRE for decreased mitochondrial transmembrane potential and Annexin V binding (A), and intracellular staining for active caspase-3 (B). Numbers show percentages (mean ± SD, n=3) of apoptotic (Annexin V+ TMRElow or active caspase-3+) CD8 T cells after 2 days of culture. *p=0.004, **p<0.001. (C) Numbers of alive T cells were counted based on trypan blue exclusion (n=3). *p<0.05. (D) CD8 T cells were labeled with CFSE and incubated with OVA peptide, control peptide or PBS for 3 days. Proliferation was analyzed by evaluation of CFSE dilution using flow cytometry. Numbers show the percentages of proliferating T cells that have undergone 3 or more times of division. *p<0.05.

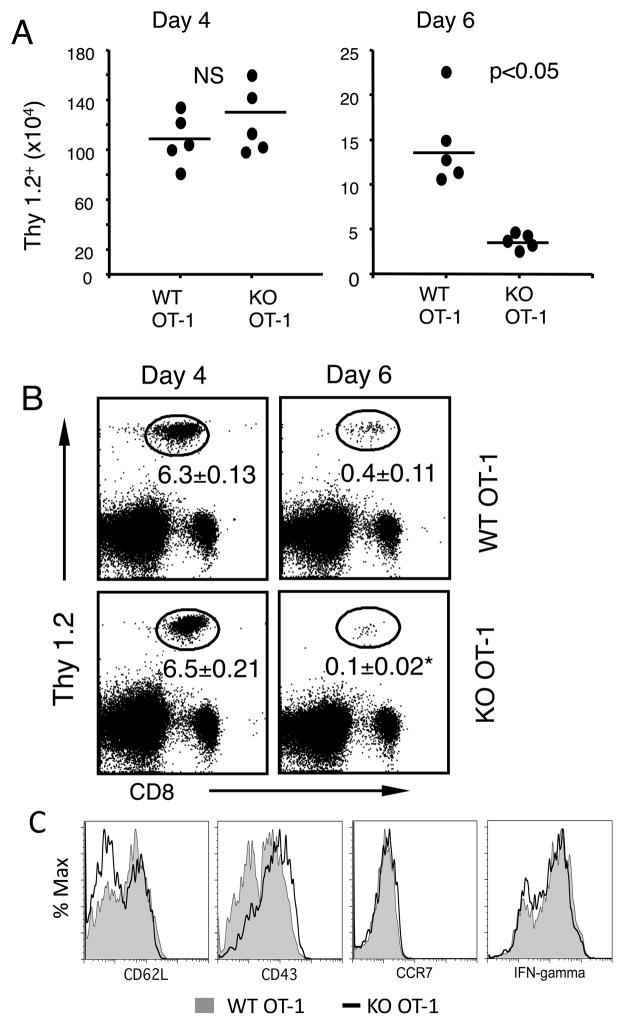

B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells have more contraction in vivo

To examine whether increased apoptosis associated with B7-H1 deficiency affects T cell expansion and contraction in vivo, we transferred naïve WT or B7-H1 KO OT-1 CD8 T cells (Thy1.2+) into cognate (Thy1.1+) B6 mice that were then immunized one day later. Similar frequencies and numbers of transferred Thy1.2+ WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells were detected in the spleens on day 4 after immunization (Fig. 4A and B). However, on day 6, a 3-fold more contraction was measured among B7-H1 KO OT-1 CD8 T cells compared to WT OT-1 CD8 T cells as shown by decreased percentages and absolute numbers of transferred B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells (Fig. 4A and B, p<0.05). Despite their difference in contraction, WT and KO OT-1 CD8 T cells differentiated into equal effector cells, as shown by comparable expression of effector T cell markers (CD62Llow CCR7low and CD43 (1B11)high) and IFN-γ production on day 4 (Fig. 4C). Thus, B7-H1 deficiency does not affect expansion or differentiation of primed CD8 T cells but may compromise survival of the effector CD8 T cells.

Figure 4. B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells have normal expansion but more robust contraction.

Purified CD8 T cells (1×106) from WT or B7-H1 KO OT-1 mice (Thy1.2+) were transferred into Thy1.1+ mice. One day after transfer, recipient mice were immunized with OVA protein and poly (I:C). On days 4 and 6 after immunization, the spleen cells were stained with anti-CD8 and anti-Thy1.2 Abs (to identify transferred OT-1 cells). (A) Comparison of numbers of transferred Thy1.2+ WT or B7-H1 KO OT-1 CD8 T cells in the spleen (n=5). NS: not significant. (B) Numbers in dot blot figures show the mean percent ± SD, n=3. *p<0.05. (C) Phenotype (CD62L, CCR7, CD43) and function (intracellular IFN-γ-producing) of WT OT-1 CD8 T cells (shaded) and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells (open line) on days 4 after immunization. Data are representative of three independent experiments with three mice per group.

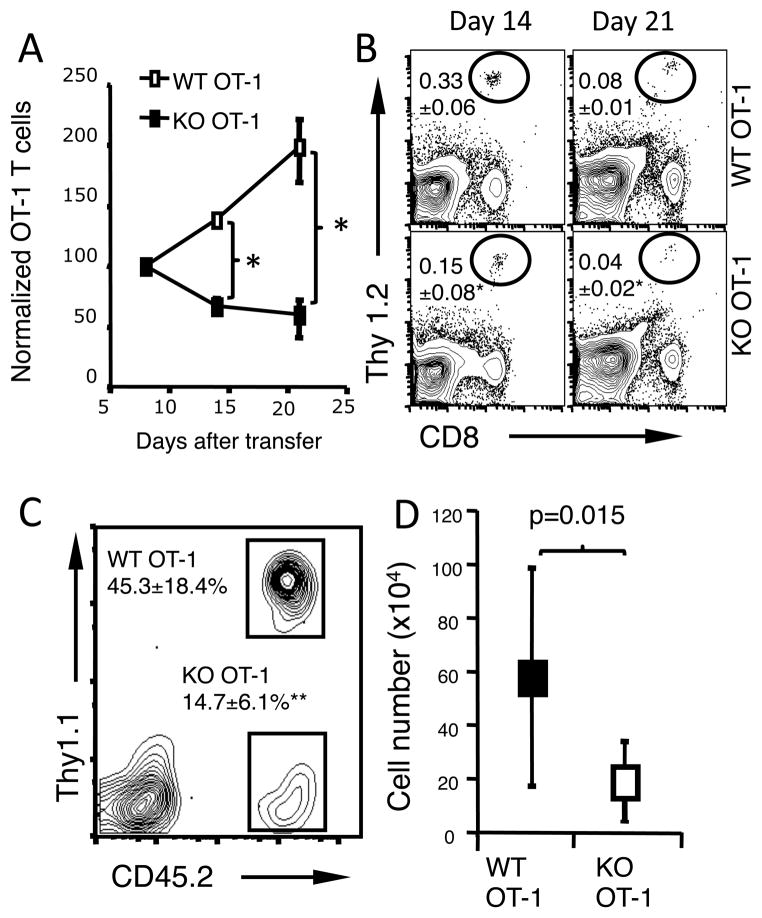

Fewer B7-H1 KO effector CD8 T cells survive in vivo

Several reports indicated that B7-H1 expressed by T cells functions in a T cell suppressive manner (22, 23). Therefore it was possible that the absence of B7-H1 on CD8 T cells could have enhanced activation-induced cell death due to continued antigen stimulation in vivo. To exclude the impact of continued antigen stimulation on effector T cell survival in vivo, we transferred pre-activated CD8 T cells into antigen-free syngeneic mice. Thy1.2+ WT and B7-H1 KO OT-1 CD8 T cells were pre-activated by incubation with anti-CD3/CD28 beads and IL-2 for 24 h. After activation, the expression of T cell activation markers (CD44, CD69 and CD25) and cytokine production were comparable between WT and B7-H1 KO OT-1 CD8 T cells (Supplemental Fig. 2A and B). Stimulating beads were removed and CD8 T cells were transferred into naïve Thy1.1+ lymphopenic mice that did not have OVA antigen. B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells did not expand as well as their WT counterparts (Fig. 5A). On days 14–21 after the transfer, the frequency of transferred B7-H1 KO Thy1.2+ CD8 T cells decreased by 2–3 fold compared with the frequency of transferred WT Thy1.2+ CD8 T cells (Fig. 5B, p<0.05).

Figure 5. Fewer pre-activated B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells survive in vivo.

Pre-activated WT or B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells (1×106) were transferred separately (A-B) or together (C-D) into naïve congenic mice (3 mice/group). (A) Normalized numbers of transferred Thy1.2+ WT or B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells in the recipient spleens. The total number of cells at day 8 after the transfer is normalized to the number transferred (100%), *p<0.05. Numbers of T cells are shown as mean ± SD of three mice per time point. (B) Percentages of recovered Thy1.2+ WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells in the Thy1.1+ recipient spleens. *p<0.05. One of three independent experiments is shown. The percentages (C) and numbers (D) of WT (Thy1.1+ CD45.2+) and B7-H1 KO (Thy1.1−CD45.2+) CD8 T cells that were co-transferred into CD45.1+ mice. Data show the percentages and numbers (mean ± SD of three mice) of recovered CD8 T cells in the recipient spleens on day 15 post-T cell transfer. **p<0.01.

In addition, we mixed pre-activated WT (Thy1.1+ CD45.2+) and B7-H1 KO (Thy1.1−CD45.2+) OT-1 CD8 T cells in equal numbers, and co-transferred them into the same CD45.1+ B6.SJL mice and analyzed their numbers on day 15 post T cell transfer. Again, the percentages and absolute numbers of transferred B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells decreased by 3-fold in the spleen of recipient mice (Fig. 5C and D, p<0.01; p<0.05). These results suggest that the increased contraction or decreased survival of B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells was not caused by over-activation from continued antigen stimulation.

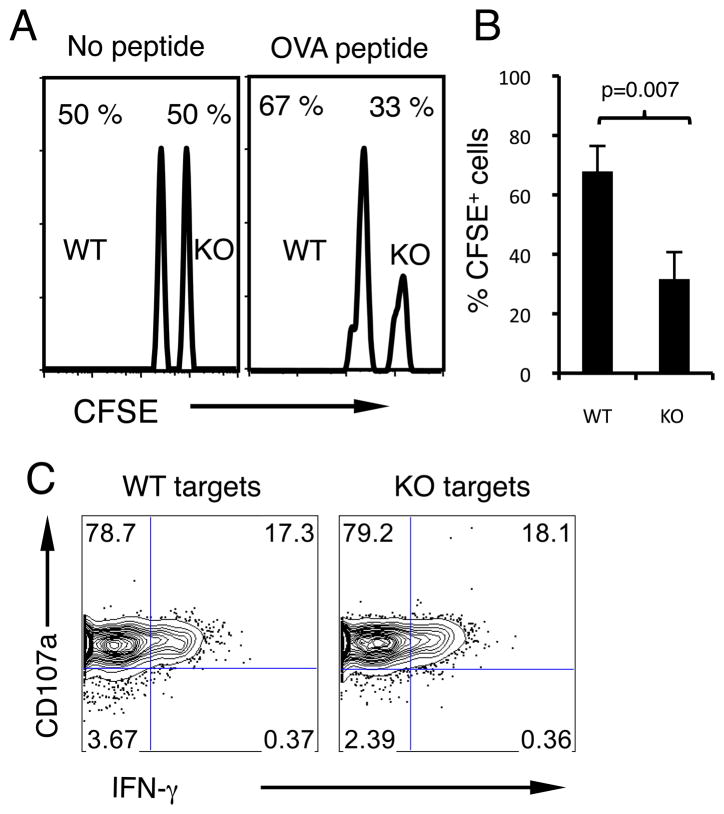

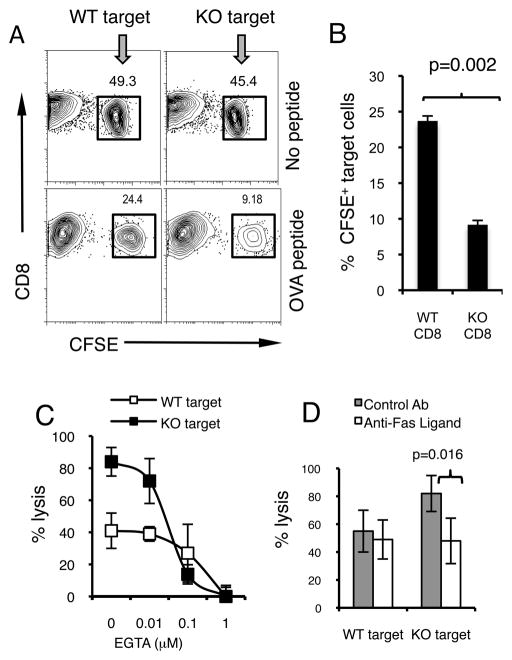

B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells are more susceptible to killing by CTLs

Because T cell fratricide is one of the proposed mechanisms responsible for T cell depletion (24–27), we examined whether decreased survival of activated B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells could be explained by increased susceptibility to killing by other cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Activated CD8 T cells from WT or B7-H1 KO C57BL/6 mice were used as target cells in an in vivo CTL assay system. Equal numbers of target WT or KO T cells loaded with or without OVA peptide were mixed and injected into C57BL/6 hosts that were immunized with OVA protein/poly (I:C) 7 days earlier. Three and a half hours after the injection, the killing of target cells by host CTLs was evaluated by staining of hosts’ spleens for the presence of transferred B7-H1 KO (CFSEhigh) or WT (CFSElow) target CD8 T cells. Without cognate antigen peptide on their surface, similar frequencies of WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells were detected in the spleens of immunized mice (Fig. 6A). However, when loaded with cognate antigen (OVA) peptide, the frequency of remained B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells decreased by 2-fold compared with WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 6A), indicating that more B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells were killed by host CTLs in an antigen-dependent way (Fig. 6B, p=0.007). It is important to note, that the increased sensitivity of B7-H1 KO target T cells to killing by CTL was not attributed to increased CTL function in the absence of B7-H1 on target cells, as OT-1 CTLs showed similar degranulation and IFN-γ production in contact with WT or B7-H1 KO target T cells in vitro (Fig. 6C). This result suggests that B7-H1 expressed by targeted T cells could make them more resistant to killing by other CTLs.

Figure 6. B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells are sensitive to killing by CTLs in vivo.

CD8 T cells from WT or B7-H1 KO B6 mice were activated and labeled with high or low dose of CFSE (2.5 μM for KO cells, 0.25 μM for WT cells). Labeled cells were then incubated with or without OVA peptide. WT and KO CD8 T cells were mixed (1:1, 2×106 of each) and injected (i.v.) into B6 mice (3 mice per group) that were immunized with OVA protein/poly I:C 7 days earlier. (A) Histogram of recovered CFSE labeled cells. Numbers indicate percentages of each population. (B) Percentages (mean ± SD, n=3) of OVA peptide-pulsed CFSE positive WT or KO CD8 T cells in the spleen of immunized mice. One of two experiments is shown. (C) Target WT or B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells were incubated with CTLs for 5 h in the presence of anti-CD107a antibody (degranulation assay) followed by intracellular staining for IFN-γ.

We next confirmed our in vivo observations using an in vitro CTL killing assay. Effector OT-1 CD8 T cells and CFSE-labeled WT or B7-H1 KO target T cells were co-cultured for 48 hours in vitro, and the percentage of CFSE+ target T cells was measured as an indicator of their loss due to killing by CTLs. As shown in Fig. 7A, the percentage of CFSE+ B7-H1 KO target CD8 T cells in cultures decreased by ~ 3-fold compared with WT target CD8 T cells (Fig. 7B, p=0.002). WT and B7-H1 KO T cells which were not loaded with OVA peptide were used as control groups, and they had similar percents of CFSE+ population in culture with CTLs (Fig. 7A upper panel), again suggesting that T cell–T cell killing is antigen-dependent and is not caused by any underlying intrinsic death signals alone. To define the exact death signals to which B7-H1 KO T cells are more sensitive, we used EGTA (a Ca2+ chelator) or anti-Fas ligand antibody and examined the effects on calcium-dependent perforin/granzyme-mediated lysis or Fas ligand-mediated killing in our in vitro system. As shown in Fig. 7C, addition of EGTA at a suboptimal blocking dose (0.1 μM) dramatically reduced the lysis of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells (from 84% to 13%, 6-fold decrease) compared with the lysis of WT CD8 T cells (from 41% to 27%, 1.5-fold decrease), suggesting that B7-H1 KO T cells are more sensitive to Ca-dependent lysis by CTLs. On the other hand, compared with control antibody, the Fas ligand-neutralizing antibody significantly suppressed Fas ligand-dependent killing of B7-H1 KO T cells (p=0.016) (Fig. 7D), suggesting that lack of B7-H1 on target T cells make them more sensitive to Fas/Fas L-mediated killing. Taken together, our results suggest that B7-H1 expressed by activated CD8 T cells may facilitate their survival by rendering them resistant to killing by other CTLs.

Figure 7. B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells are more sensitive to killing by CTLs in vitro.

Splenic CD8 T cells from WT or B7-H1 KO C57BL/6 mice (3 mice per group) were labeled with CFSE and loaded with or without OVA peptide and used as target cells. Pre-activated OT-1 CD8 T cells were used as effector cells. Effector OT-1 T cells and target CD8 T cells (CFSE+) were co-cultured for 48 hours and the percentage of CFSE+ target T cells was measured as an indicator of their killing (A). One representative result of three independent experiments is shown. (B) Data show the percentages (mean ± SD, n=3) of surviving CFSE+ CD8+ target T cells after 2 days of incubation. Graded EGTA (C) or Fas ligand neutralizing Ab (10 μg/ml) (D) was added to culture for 48 h. Percent lysis is calculated as: (1- %CFSE+ of target with OVA peptide/% CFSE+ of target without peptide) × 100%. Data show mean % lysis ± SD of three mice.

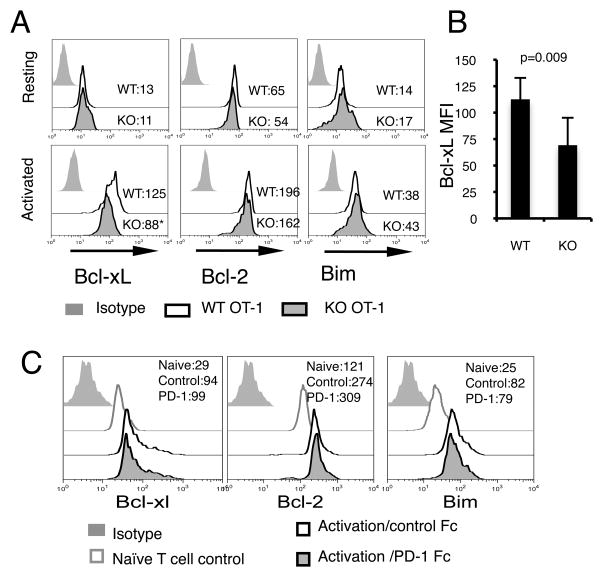

Lower levels of Bcl-xL in activated B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells

Next we wanted to define the exact molecular mechanisms that are responsible for increased sensitivity of activated B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells to CTL lysis. We first examined the expression of Fas. Both resting and activated WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells expressed comparable levels of Fas on their surface (Supplemental Fig. 2C), suggesting that increased cell death of activated B7-H1 KO T cells is not due to increased Fas expression. As the increased apoptosis of B7-H1 KO T cells was accompanied with decreased mitochondrial transmembrane potential (lower levels of TMRE in Fig. 3A), we hypothesized that B7-H1 deficiency may lead to alterations in mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. To test this, we measured the protein expressions of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bim in both resting and activated T cells. Intracellular staining revealed similar levels of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bim in resting WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells (Fig. 8A). However, in activated T cells, Bcl-xL levels were significantly lower in B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells than in WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 8A and B, p=0.009). The levels of Bcl-2 and Bim on the other hand remained comparable between activated WT and B7-H1 KO T cells. To investigate whether B7-H1 ligation would affect Bcl-xL expression, we incubated WT T cells with plate-bound PD-1 Fc fusion protein to engage B7-H1 on T cells in the presence of TCR/CD28 stimulation. Even though TCR/CD28 stimulation up-regulated Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and Bim, ligation of B7-H1 by PD-1 did not have additional effects on their expression (Fig. 8C). This suggests that B7-H1 ligation, at least by PD-1, may not directly affect Bcl-xL protein levels, and that B7-H1 expressed by activated T cells may have an intrinsic, ligand-independent role in regulation of Bcl-xL protein. Taken together, our observations suggest that in the absence of B7-H1, activated CD8 T cells express reduced levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL. Although the differences in Bcl-xL levels might not be sufficient to result in initiating the apoptosis of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells when acting alone, they could render them more susceptible to additional pro-apoptotic stimuli such as cytokine withdrawal, Fas L- and lytic molecule- mediating CTL lysis.

Figure 8. Bcl-xL protein expression is regulated by B7-H1 in activated CD8 T cells.

Purified CD8 T cells from WT or B7-H1 KO OT-1 mice (three mice/group) were either stained freshly or after activation with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 48 hours. (A) Intracellular staining for Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, Bim in resting and activated CD8 T cells. Numbers show the MFI (mean fluorescence intensity). *p<0.01 compared with WT cells. (B) Bar graph of average MFI of Bcl-xL expressed by activated WT and B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells (mean ± SD, n=3). One of two independent experiments is shown. (C) B7-H1 ligation did not increase Bcl-xL. Freshly purified naive CD8 T cells from WT mice were incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads in the presence of plate- bound PD-1 Fc fusion protein (10 μg/ml) or control Fc fusion protein. Histograms show Intracellular staining for Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and Bim in CD8 T cells 48 h after activation with or without B7-H1 ligation. Naïve CD8 T cells were used as control for baseline expression of these molecules.

B7-H1 deficient effector CD8 T cells fail to mount a protective immunity

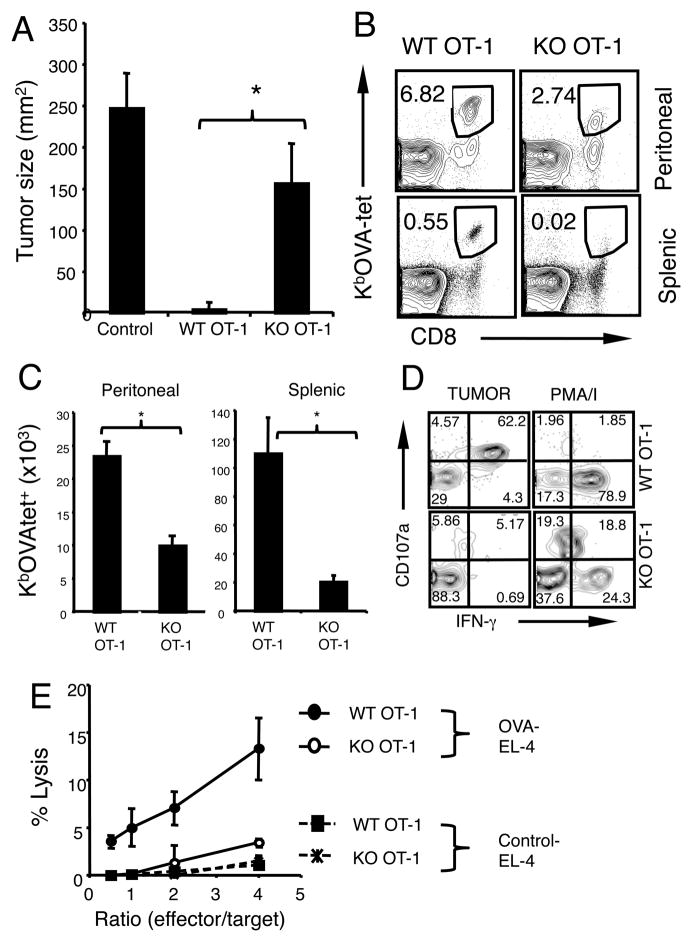

Next we examined the ability of B7-H1 deficient effector CD8 T cells to mount protective immunity against tumor challenge. WT and B7-H1 KO effector OT-1 CD8 T cells (prepared as in Fig. 5) were transferred (i.v.) into recipient mice that had been irradiated (600 rad) one day earlier. One day after T cell transfer, recipient mice were injected (s.c.) with OVA-expressing B16 tumor cells. While B16-OVA tumors progressively grew in the control group of mice without effector T cells transfer, they did not grow out in the mice that received WT effector CD8 T cells (Fig. 9A). However, the growth of B16-OVA tumors could not be completely suppressed in mice transferred with B7-H1 KO effector CD8 T cells (Fig. 9A, p<0.05), suggesting that B7-H1 deficient effector CD8 T cells may have compromised protective function.

Figure 9. B7-H1 deficient CD8 T cells show impaired protective immunity against tumor challenge.

Pre-activated WT and B7-H1 KO OT-1 CD8 T cells (1×106) were transferred (i.v.) into sub-lethally irradiated B6 mice. (A) One day post T cell transfer, recipient mice were injected with B16-OVA tumors (5×105) subcutaneously in the right flank. Tumor sizes are shown as mean ± SD of five mice per group. * p<0.05. (B–C) EG7-OVA tumor cells were injected (i.p.) on day 7 post T cell transfer. One week after tumor injection, transferred OT-1 CD8 T cells were identified by staining with anti-CD8 and KbOVA-tetramer (tet) in the peritoneal cavities and spleen. Numbers show the percentage of tet+ CD8 T cells (B). Actual numbers of transferred OT-1 CD8 T cells (C). Data show mean ± SD of three mice, *p<0.05. (D) CTL activity of transferred CD8 T cells harvested from peritoneal cavities was analyzed by degranulation (CD107a expression) and intracellular production of IFN-γ after incubation with EG7 tumor cells or PMA/ionomycin. (E) Cytolytic activity in the spleen of recipient mice. EL-4 cells that were pulsed with OVA peptide (solid lines) or with control peptide (dotted lines) were used as target cells in 4 hr calcein release assay. Data are representative of three independent experiments with three mice per group.

To examine the accumulation and function of effector CD8 T cells in tumor site, we injected EG7-OVA tumor cells into the peritoneal cavities one week after T cell transfer and monitored the presence of effector OT-1 CD8 T cells in the peritoneal cavities and spleens. Transferred OT-1 CD8 T cells were identified by KbOVA tetramer staining. Following tumor challenge, the frequency and numbers of KbOVA-tet+ CD8 T cells decreased by 2–5-fold in the peritoneal cavities and spleens of recipients of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells compared to recipients of WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 9B and C, p<0.05). CTL function of the transferred effector CD8 T cells was also measured in the peritoneal cavities and spleens of recipient mice. In peritoneal cavities, the frequency of CD107a+ IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells that were reactive to tumor cells decreased by 12-fold in recipients of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells compared with recipients of WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 9D). Observed reduced tumor reactivity of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells could be due to antigen-specific anergy as they could produce IFN-γ+ when they were stimulated with PMA (phorbol myristate acetate)/ionomycin that bypasses early TCR/CD28 signaling (Fig. 9D). Consistent with this, cytolytic activity in the spleens of recipients of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells decreased by 4–7 fold compared to recipients of WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 9E). Taken together, our results suggest that B7-H1 deficient effector CD8 T cells could not mount protective immunity due to compromised cytolytic activity resulting from their reduced accumulation.

DISCUSSION

In this study we show that B7-H1 expressed by activated CD8 T cells is essential for their survival following antigen stimulation. Increased apoptosis results in depletion of B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells during the contraction phase. The decreased levels of Bcl-xL in activated B7-H1 KO CD8 T cells, renders T cells more sensitive to cytokine withdrawal and killing by other CTLs. The highest level of B7-H1 expression by antigen-primed T cells during the contraction phase help effector T cells survive by maintaining elevated levels of Bcl-xL which counteracts intense apoptotic signals. Therefore, disturbing T cell B7-H1 by blocking antibody at this stage would result in loss of effector cells. Transfer of B7-H1 deficient effector CD8 T cells may not be able to mount a protective immunity against tumor challenge. Thus, this novel pro-survival function of B7-H1 expressed by CD8 T cells has important implications in T cell survival and protective T cell immunity.

Unlike Bcl-2 protein that is constitutively expressed by T cells, Bcl-xL protein levels vary with different levels of T cell activation (28). Its expression is induced by TCR stimulation and up-regulated by CD28 signals (28). However, it is not stable and begins to decline at 48 h after activation (28). It has been shown that enhanced Bcl-xL expression prevents T cell death in response to Fas/Fas L signaling and cytokine withdrawal (28, 29). In addition, there is a direct regulatory relationship between anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL and pro-apoptotic Fas mediated pathway, as Fas-pathway signaling induces degradation of Bcl-xL via activation of p38MAPK in CD8 T cells (30). In contrast, T cell survival factor IL-7 has been shown to exert its functions through up-regulation of Bcl-xL in effector/memory T cells (31). To our knowledge, since the report of CD28 signals enhancing Bcl-xL expression (28), no other B7 co-stimulatory molecule has been directly linked to Bcl-xL expression. Our finding that the loss of B7-H1 is correlated with lower levels of Bcl-xL is novel and unexpected, because it has been believed that B7-H1 functions as a suppressive regulator for T cells (7). Currently, we do not know how B7-H1 regulates Bcl-xL expression during T cell activation. Because B7-H1 ligation by PD-1 did not affect Bcl-xL expression (Fig. 8C), it is possible that B7-H1 regulates Bcl-xL in an intrinsic ligand-independent manner. However other non-PD-1 ligands cannot be excluded. Further investigation is necessary to address the biochemical mechanisms underlying B7-H1-mediated regulation of Bcl-xL expression.

Several studies have proposed an inhibitory function of B7-H1 expressed by T cells based on proliferation and cytokine production during primary T cell activation (22, 23). In those studies, B7-H1 deficient T cells produced more IFN-γ but did not exhibit increased proliferation. However, the apoptosis of B7-H1 deficient T cells in those studies was not examined. We report that B7-H1 expressed by activated T cells may protect them from being killed by other CTLs (Fig. 6–7). This function of B7-H1 does not seem to be due to its suppressive effects on CTL function (Fig. 6C). Goldberg et al. has previously reported that B7-H1 KO and WT whole spleen cells show identical sensitivity to killing by CTLs in vivo (32). Although our results agree with their finding to the extent of B7-H1 on target cells not having effect on lytic function of effector CTLs, our in vivo and in vitro killing assays suggest the net affect of B7-H1 absence on target CD8 T cells is to compromise survival of target cells. Goldberg et al. used resting (non-activated) whole spleen cells, which might have not expressed sufficient levels of B7-H1 and Bcl-xL to provide protection from killing by CTLs. In contrast, purified CD8 T cells used in our systems were first activated for 48 h to up-regulate B7-H1 and Bcl-xL (Fig. 6–7). Taken together, our results suggest up-regulation of B7-H1 by activated T cells is essential for upregulation or maintenance of Bcl-xL to prevent activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Although reduction in Bcl-xL levels alone might not be sufficient to result in apoptosis, it can make CD8 T cells more sensitive to additional apoptotic stimuli such as ligation of Fas or release of lytic granules, both delivered by CTL during the contraction phase of an immune response.

The biological significance of our observations is that disruption of B7-H1’s pro-survival function results in loss of effector cells and compromises generation of protective immunity against malignancy (Fig. 9) or infection. Two groups using similar models of primary infection with Listeria monocytogenes reported that B7-H1 blockade impairs the expansion of pathogen-specific effector CD8 T cells and suppresses the antibacterial protection in the host (10, 33). In addition, B7-H1 deficiency has led to compromised protection to primary Salmonella infection (13). On the other hand, suppression of B7-H1’s pro-survival function may mitigate the harm of autoimmunity. In an autoimmune disease model, B7-H1 blockade inhibits the function of effector T cells and alleviates chronic intestinal inflammation (12). Moreover, a transient loss of self-reactive effector T cells has been observed in B7-H1 deficient mice following immunization with MOG peptide (34). While those reports support a positive co-stimulatory role of B7-H1 during the priming of effector T cells (1, 35, 36), our data suggest that B7-H1 blockade or deficiency may disturb its pro-survival function during the late effector and contraction phases of an immune response. It will be important to ascertain the impact of B7-H1 blockade on the expression or degradation of Bcl-xL in effector CD8 T cells to better control loss of protective T cell immunity or to heighten T cell tolerance in autoimmunity and transplantation settings.

In summary, our findings suggest that B7-H1 expressed by activated CD8 T cells is essential for their survival. A more thorough understanding of the function of B7-H1 expressed by activated T cells would provide new insights not only into the regulation of T cell survival required for protective immunity, but also into alleviation of autoimmune diseases and preservation of transplants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Lieping Chen (Johns Hopkins University), Tian Tian (Harvard University) and Richard Vile (Mayo Clinic) for providing us with B7-H1 KO mice, Thy1.1 OT-1 mice and B16-OVA tumor cells.

This work was supported by Mayo Foundation Career Development Award, in part by Mayo Clinic Cancer Center/American Cancer Society’s New Investigator Award and NIH/NCI R01 CA134345.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- B7-H1

B7 homologue 1

- PD-1

programmed death 1

- OVA

ovalbumin

- KO

knockout

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat Med. 1999;5:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/70932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, Lennon VA, Celis E, Chen L. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zang X, Allison JP. The B7 family and cancer therapy: costimulation and coinhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5271–5279. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong H, Chen L. B7-H1 pathway and its role in the evasion of tumor immunity. J Mol Med. 2003;81:281–287. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flies DB, Chen L. The new B7s: playing a pivotal role in tumor immunity. J Immunother. 2007;30:251–260. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31802e085a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zha Y, Blank C, Gajewski TF. Negative regulation of T-cell function by PD-1. Crit Rev Immunol. 2004;24:229–237. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v24.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamazaki T, Akiba H, Iwai H, Matsuda H, Aoki M, Tanno Y, Shin T, Tsuchiya H, Pardoll DM, Okumura K, Azuma M, Yagita H. Expression of programmed death 1 ligands by murine T cells and APC. J Immunol. 2002;169:5538–5545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong H, Strome SE, Matteson EL, Moder KG, Flies DB, Zhu G, Tamura H, Driscoll CL, Chen L. Costimulating aberrant T cell responses by B7-H1 autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:363–370. doi: 10.1172/JCI16015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowe JH, Johanns TM, Ertelt JM, Way SS. PDL-1 blockade impedes T cell expansion and protective immunity primed by attenuated Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2008;180:7553–7557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo SK, Jeong HY, Park SG, Lee SW, Choi IW, Chen L, Choi I. Blockade of endogenous B7-H1 suppresses antibacterial protection after primary Listeria monocytogenes infection. Immunology. 2007;123:90–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanai T, Totsuka T, Uraushihara K, Makita S, Nakamura T, Koganei K, Fukushima T, Akiba H, Yagita H, Okumura K, Machida U, Iwai H, Azuma M, Chen L, Watanabe M. Blockade of B7-H1 suppresses the development of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2003;171:4156–4163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, O’Donnell H, McSorley SJ. B7-H1 (programmed cell death ligand 1) is required for the development of multifunctional Th1 cells and immunity to primary, but not secondary, Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:2442–2449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Flies DB, van Deursen JM, Chen L. B7-H1 determines accumulation and deletion of intrahepatic CD8(+) T lymphocytes. Immunity. 2004;20:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahonen CL, Doxsee CL, McGurran SM, Riter TR, Wade WF, Barth RJ, Vasilakos JP, Noelle RJ, Kedl RM. Combined TLR and CD40 triggering induces potent CD8+ T cell expansion with variable dependence on type I IFN. J Exp Med. 2004;199:775–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Price DADRSC, DDCRM, Koup RA. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J Immunol Methods. 2003;281:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenfels R, Biddison WE, Schulz H, Vogt AB, Martin R. CARE-LASS (calcein-release-assay), an improved fluorescence-based test system to measure cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. J Immunol Methods. 1994;172:227–239. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pulko V, Liu X, Krco CJ, Harris KJ, Frigola X, Kwon ED, Dong H. TLR3-stimulated dendritic cells up-regulate B7-H1 expression and influence the magnitude of CD8 T cell responses to tumor vaccination. J Immunol. 2009;183:3634–3641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilon-Thomas S, Mackay A, Vohra N, Mule JJ. Blockade of programmed death ligand 1 enhances the therapeutic efficacy of combination immunotherapy against melanoma. J Immunol. 2010;184:3442–3449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirano F, Kaneko K, Tamura H, Dong H, Wang S, Ichikawa M, Rietz C, Flies DB, Lau JS, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. Blockade of B7-H1 and PD-1 by monoclonal antibodies potentiates cancer therapeutic immunity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayaraman S. Flow cytometric determination of mitochondrial membrane potential changes during apoptosis of T lymphocytic and pancreatic beta cell lines: comparison of tetramethylrhodamineethylester (TMRE), chloromethyl-X-rosamine (H2-CMX-Ros) and MitoTracker Red 580 (MTR580) J Immunol Methods. 2005;306:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latchman YE, Liang SC, Wu Y, Chernova T, Sobel RA, Klemm M, Kuchroo VK, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10691–10696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307252101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seo SK, Seo HM, Jeong HY, Choi IW, Park YM, Yagita H, Chen L, Choi IH. Co-inhibitory role of T-cell-associated B7-H1 and B7-DC in the T-cell immune response. Immunol Lett. 2006;102:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su MW, Pyarajan S, Chang JH, Yu CL, Jin YJ, Stierhof YD, Walden P, Burakoff SJ. Fratricide of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes is dependent on cellular activation and perforin-mediated killing. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2459–2470. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chai JG, Bartok I, Scott D, Dyson J, Lechler R. T:T antigen presentation by activated murine CD8+ T cells induces anergy and apoptosis. J Immunol. 1998;160:3655–3665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanon E, Stinchcombe JC, Saito M, Asquith BE, Taylor GP, Tanaka Y, Weber JN, Griffiths GM, Bangham CR. Fratricide among CD8(+) T lymphocytes naturally infected with human T cell lymphotropic virus type I. Immunity. 2000;13:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vahlenkamp TW, Bull ME, Dow JL, Collisson EW, Winslow BJ, Phadke AP, Tompkins WA, Tompkins MB. B7+CTLA4+ T cells engage in T-T cell interactions that mediate apoptosis: a model for lentivirus-induced T cell depletion. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2004;98:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boise LH, Minn AJ, Noel PJ, June CH, Accavitti MA, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-XL. Immunity. 1995;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scaffidi C, Fulda S, Srinivasan A, Friesen C, Li F, Tomaselli KJ, Debatin KM, Krammer PH, Peter ME. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1675–1687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farley N, Pedraza-Alva G, Serrano-Gomez D, Nagaleekar V, Aronshtam A, Krahl T, Thornton T, Rincon M. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates the Fas-induced mitochondrial death pathway in CD8+ T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2118–2129. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2118-2129.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chetoui N, Boisvert M, Gendron S, Aoudjit F. Interleukin-7 promotes the survival of human CD4+ effector/memory T cells by up-regulating Bcl-2 proteins and activating the JAK/STAT signalling pathway. Immunology. 2010;130:418–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg MV, Maris CH, Hipkiss EL, Flies AS, Zhen L, Tuder RM, Grosso JF, Harris TJ, Getnet D, Whartenby KA, Brockstedt DG, Dubensky TW, Jr, Chen L, Pardoll DM, Drake CG. Role of PD-1 and its ligand, B7-H1, in early fate decisions of CD8 T cells. Blood. 2007;110:186–192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seo SK, Jeong HY, Park SG, Lee SW, Choi IW, Chen L, Choi I. Blockade of endogenous B7-H1 suppresses antibacterial protection after primary Listeria monocytogenes infection. Immunology. 2008;123:90–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortler S, Leder C, Mittelbronn M, Zozulya AL, Knolle PA, Chen L, Kroner A, Wiendl H. B7-H1 restricts neuroantigen-specific T cell responses and confines inflammatory CNS damage: implications for the lesion pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1734–1744. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subudhi SK, Zhou P, Yerian LM, Chin RK, Lo JC, Anders RA, Sun Y, Chen L, Wang Y, Alegre ML, Fu YX. Local expression of B7-H1 promotes organ-specific autoimmunity and transplant rejection. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:694–700. doi: 10.1172/JCI19210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahl C, Bochtler P, Chen L, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. B7-H1 on hepatocytes facilitates priming of specific CD8 T cells but limits the specific recall of primed responses. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:980–988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.