Abstract

Extracellular adenosine and purine nucleotides are elevated in many pathological situations associated with the expansion of CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Therefore, we tested whether adenosinergic pathways play a role in MDSC expansion and functions. We found that A2B adenosine receptors on hematopoietic cells play an important role in accumulation of intratumoral CD11b+Gr1high cells in a mouse Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) model in vivo and demonstrated that these receptors promote preferential expansion of the granulocytic CD11b+Gr1high subset of MDSCs in vitro. Flow cytometry analysis of MDSCs generated from mouse hematopoietic progenitor cells revealed that the CD11b+Gr-1high subset had the highest levels of CD73 (ecto-5′-nucleotidase) expression (ΔMFI of 118.5±16.8), followed by CD11b+Gr-1int (ΔMFI of 57.9±6.8) and CD11b+Gr-1−/low (ΔMFI of 12.4±1.0). Even lower levels of CD73 expression were found on LLC tumor cells (ΔMFI of 3.2±0.2). The high levels of CD73 expression in granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high cells correlated with high levels of ecto-5′-nucletidase enzymatic activity. We further demonstrated that the ability of granulocytic MDSCs to suppress CD3/CD28-induced T cell proliferation is significantly facilitated in the presence of the ecto-5′-nucletidase substrate 5′-AMP. We propose that generation of adenosine by CD73 expressed at high levels on granulocytic MDSCs may promote their expansion and facilitate their immunosuppressive activity.

INTRODUCTION

Accumulating evidence suggests that the endogenous nucleoside adenosine plays an important role in regulation of inflammation and immunity. Extracellular adenosine exerts its actions via cell surface G protein-coupled adenosine receptors. Four subtypes of adenosine receptors have been cloned and classified as A1, A2A, A2B and A3.(1). It has been long recognized that adenosine can suppress T cell activity (2,3) by acting on A2A adenosine receptors (4–9). Recently, it has been proposed that generation of pericellular adenosine by the ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) expressed on regulatory CD4+Fox3+ T lymphocytes is a contributing factor to their immunosuppressive properties (10–12). Furthermore, this adenosinergic mechanism of immune suppression was also suggested to play an important role in the ability of tumors to escape from host immunosurveillance (13,14).

In addition to regulatory T lymphocytes, nonlymphoid cells with immunosuppressive properties have been identified and named myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). In mice, these cells represent a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells with monocytic and granulocytic morphology that are generally characterized as CD11b+Gr-1+ cells. Accumulation of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells has been documented in mice with cancer, and these cells are considered a major contributor to the tumor immuntolerance (15,16). Expansion of MDSC populations is associated not only with tumors, but also with acute and chronic inflammation, traumatic stress, and transplantation (15,17). Importantly, these pathological conditions are known to be associated with an increased release of purine nucleotides from the affected cells, an event that eventually leads to a rise in extracellular adenosine concentrations (18). However, a potential role of adenosine and adenosinergic mechanisms in the expansion of MDSCs and their functions has not been studied.

Among the adenosine receptors, the A2B subtype has the lowest affinity for adenosine. In contrast to other adenosine receptor subtypes, A2B receptors are thought to remain silent under normal physiological conditions when interstitial adenosine levels are low and become active in pathological conditions when local adenosine levels can reach micromolar concentrations (19). The A2B adenosine receptor has recently emerged as an important regulator of immune cell differentiation (20). We have demonstrated that A2B adenosine receptors skew differentiation of dendritic cells from hematopoietic progenitors and monocytes into cells with tolerogenic and pro-angiogenic phenotype (21). Our recent studies in a Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) isograft model showed that, compared to wild type (WT) controls, A2B receptor knockout (A2BKO) mice exhibited significantly attenuated tumor growth and longer survival times after inoculation with LLC cells (22). In the present study, we used the same tumor model in vivo and an established model of MDSC generation in vitro (23) to demonstrate that A2B receptors but not other adenosine receptor subtypes promote preferential expansion of granulocytic CD11b+Gr1high MDSCs. Furthermore, our new data suggest that generation of pericellular adenosine by the ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73), which is highly expressed on these cells may contribute to their immunosuppressive properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Endonorbornan-2-yl-9-methyladenine (N-0861) was a gift from Whitby Research, Inc. (Richmond, VA) and 5-amino-7-(phenylethyl)-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo-[1,5-c]-pyrimidine (SCH58261) was a gift from Drs C. Zocchi and E. Ongini (Schering Plough Research Institute, Milan, Italy). 3-isobutyl-8-pyrrolidinoxanthine (IPDX) was synthesized as previously described (24). 3-Ethyl-1-propyl-8-{1-[3-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl}-3,7-dihydro-1H-purine-2,6-dione (CVT-6883) was provided by CV Therapeutics (Palo Alto, CA). N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA), 4-((N-ethyl-5′-carbamoyladenos-2-yl)-aminoethyl)-phenyl-propionic acid (CGS21680), 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), 3-Ethyl-5-benzyl-2-methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (MRS1191), adenosine-5′-monophosphate (AMP), adenosine 5′-(α, β-methylene) diphosphate (APCP), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). When used as a solvent, final DMSO concentrations in all assays did not exceed 0.1% and the same DMSO concentrations were used in vehicle controls.

Mice

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the US National Institutes of Health. Animal studies were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Vanderbilt University. Eight- to twelve-week-old age- and sex-matched mice were used. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). A1 adenosine receptor knockout (A1KO) mice were obtained from Dr. Jürgen Schnermann, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD); A2AKO mice were obtained from Dr. Jiang-Fan Chen, Boston University (Boston, MA); A3KO mice were obtained from Marlene Jacobson, Merck Research Laboratories (West Point, PA); and A2BKO mice were obtained from Deltagen (San Mateo, CA). All of the knockout mice used in these studies were back-crossed to the C57BL/6 genetic background for more than 10 generations.

Bone marrow transplantation and LLC tumor model

For generation of bone marrow chimeric mice, eight-week-old WT recipient mice were maintained on acidified water containing antibiotics for 3 days before, and 14 days after transplantation. Bone marrow single cell suspensions were prepared from WT and A2BKO donor mice as previously described (25). Four-six hours before transplantation, recipient mice received lethal whole body irradiation (9 Gy) using cesium gamma source. Donor bone marrow cells (5×106 in 100 μl of sterile PBS) were injected into the retro-orbital venous plexus of the recipient mice. Eight weeks after transplantation, A2B receptor bone marrow-chymeric mice had greater than 90% of the hematopoietic cells replaced as assessed by the expression of A2B receptors in blood cells using RT-PCR. Bone marrow chymeric or normal mice were used as hosts for LLC tumors.

For generation of tumor isografts, Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA; Catalog No. CRL-1642) were propagated in ATCC-formulated Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Catalog No. 30-2002) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1X Antibiotic-Antimycotic mixture (Sigma) under humidified atmosphere of air/CO2 (19:1) at 37°C. LLC cells were dislodged from cell culture plates by repetitive pipetting with sterile PBS, and then pelleted by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in PBS and counted using a hemocytometer. A final concentration was adjusted to 5×106 cells/ml, and 100 μl of cell suspension was injected subcutaneously into the right flank using a tuberculin syringe and a 27-gauge needle. Animals were inspected daily; in all events, tumors did not exceed 2 cm in diameter or 10 % of animal weight. Mice were killed on day 14 after LLC cell inoculation. To prepare single cell suspensions, extracted tumors were chopped into small pieces, incubated in DMEM medium with 10% FBS, 1500 U/ml collagenase (Sigma) and 1000 U/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma) for 1 hour at 37° C, and then passed through a cell strainer. Total cell numbers were counted and CD45+ cell populations that represent tumor-infiltrating host immune cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Generation of MDSCs from bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors

Bone marrow cells were harvested from the femurs of wild type or adenosine receptor knockout mice. Hematopoietic progenitor cells (Lin−) were isolated using lineage cell depletion kit and LS columns from Miltenyi Biotec Inc. (Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Resulting cells were >50% CD117-positive as assayed by flow cytometry. Hematopoietic progenitor cells were cultured on 24-well plates at 5 × 104 cells/mL concentration in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS, 20 mM Hepes, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1X antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and supplemented with granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 10 ng/mL) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml; both from R&D systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) for 5 days under humidified atmosphere of air/CO2 (19:1)at 37° C as previously described (23).

Magnetic sorting

Enrichment of CD11b+Gr-1high cell subpopulations of MDSCs was carried according to a previously published protocol (26). In brief, after treatment with FcR Blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.), bone marrow-derived MDSCs (107 cells/ml) were stained with 5 μl per ml of anti-mouse Ly-6G-biotin antibody (Clone 1A8, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) for 10 min followed by washing and incubation with 20 μl per ml of anti-biotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.) for 15 min at 4°C. The cells were then washed and resuspended in dilution buffer for magnetic cell separation. The labeled cells were passed through MS separation columns that had been equilibrated with dilution buffer. Columns were washed three times with 3 ml of dilution buffer. The retained Ly-6G positive cells were eluted from the column outside the magnetic field by pipetting 5 ml of dilution buffer onto the column. Resulting cell preparations were analyzed for CD11b and Gr-1 cell surface expression by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

After treatment with FcR Blocking Reagent, cells (106 cells/ml) were incubated with the relevant antibodies for 20 minutes at 4°C. If not stated otherwise, all antibodies were obtained from eBioscience, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Data acquisition was performed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and the data were analyzed with WinList 5.0 software. Antigen negativity was defined as having the same fluorescent intensity as the isotype control. FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences) was used to isolate CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int or CD11b+Gr-1high cell subpopulations.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Real-time RT-PCR was performed on an ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers for murine arginase 1 (Arg1) were: 5′-GAG GAA AGC TGG TCT GCT G-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAC AAT TTG AAA GGA GCT GTC-3′ (reverse), for inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were: 5′-GAC AAG CTG CAT GTG ACA TC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTT GGA CTT GCA AGT GAA ATC-3′ (reverse), and for β-actin were: 5′-AGT GTG ACG TTG ACA TCC GTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCC AGA GCA GTA ATC TCC TTC T-3′ (reverse).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

The oxidation-sensitive dye 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used for the measurement of ROS production. Cells (106/ml) were incubated in serum-free RPMI medium containing 2 μM CM-H2DCFDA in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of PMA at 37°C for 30 min, washed with PBS, and then labeled with anti-CD11b-PE and anti-Gr-1-PE-Cy7 (clone RB6-8C5) antibodies. After incubation for 20 min at 4°C, cells were washed with PBS and analyzed using flow cytometry.

Ecto-5′-nucleotidase assay

Ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity was measured in MDSC subpopulations isolated by cell sorting on FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Cells were washed twice in cold phosphate-free buffer and resuspended in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 buffer containing 2 mM MgCl2, 120 mM NaCI, 5 mM KCI, 10 mM glucose and 5 mM tetramisole at a concentration of 105 cells/ml. Reaction was started by addition of AMP to a final concentration of 1 mM and carried out at 37°C for 40 min. Reaction was stopped with the addition of trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 5% and immediately put on ice. The release of inorganic phosphate (Pi) was measured by the malachite green method as described by Baykov et al (27). The non-enzymatic Pi released from nucleotide into assay medium without cells and Pi released from cells incubated without nucleotide was subtracted from the total Pi released during incubation, giving net values for enzymatic activity. All samples were run in triplicate. Specific activity is expressed as μmol Pi released/min/106 cells.

T cell proliferation assay

T cells were isolated from the spleen of naïve C57BL6 mice by using T cell enrichment columns (R&D system, Minneapolis, MN). T cells were seeded in triplicates at a concentration of 105 cells/well in U-bottom 96-well plates containing CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and cultured in the absence or presence of AMP together with bone marrow-derived CD11b+Gr1high cells at concentrations indicated in the Results section. After 72 h of incubation, 3[H]-thymidine was added at 1 μCi per well for an additional 18 hours of incubation followed by cell harvesting and radioactivity count using a liquid scintillation counter.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) and presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between several treatment groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post-tests. Comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tailed unpaired t tests. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Stimulation of A2B but not other adenosine receptor subtypes promotes expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells

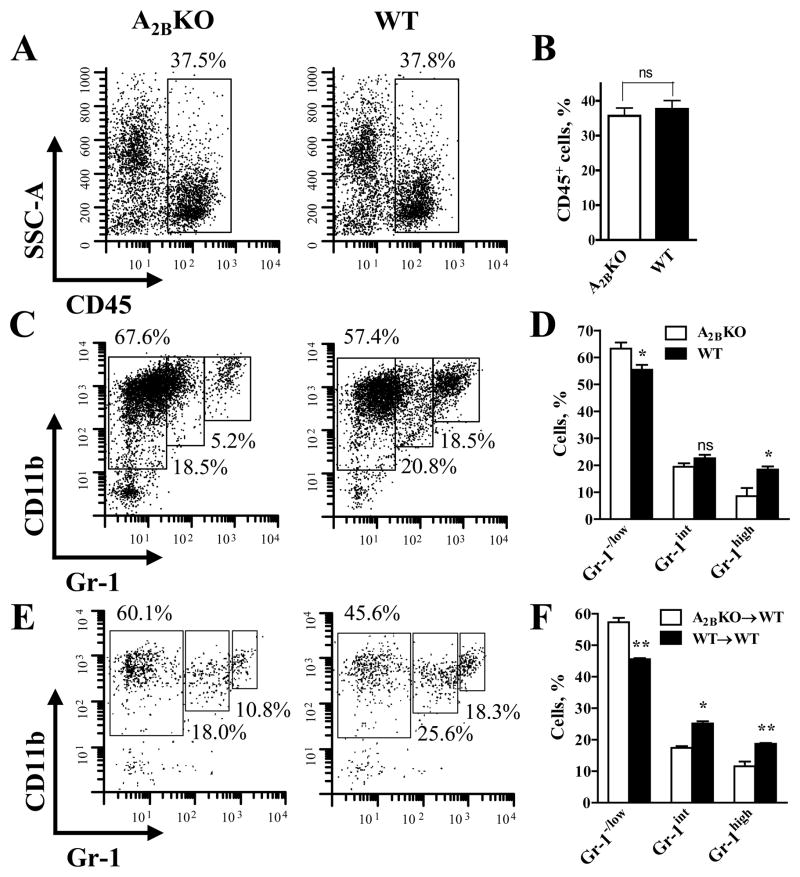

Distinct subpopulations of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells have been previously described based on their expression of the myeloid differentiation antigen Gr-1. Three subsets of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells, i.e. CD11b+Gr-1low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high have been recently characterized morphologically, phenotypically and functionally in several murine tumor models (23,26,28,29). We analyzed CD45+ immune cells in LLC tumors grown in A2BKO and WT mice using antibodies against CD11b and Gr-1. Flow cytometric analysis of tumor single cell suspensions shows that the proportion of tumor-infiltrating CD45+ host immune cells was similar in tumors extracted from A2BKO and WT mice (Figure 1A, B). However, the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1high cells was significantly higher in WT compared to A2BKO mice (18.4±1.2 vs. 8.6±3.0%, respectively; P<0.05, n=3), whereas the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1−/low cells was significantly lower (55.5±1.7 vs. 63.3+2.2%, respectively; P<0.05, n=3). The decrease in proportion of monocytic CD11b+Gr-1−/low cells correlated with lower frequency of cells expressing F4/80, CD11c, and MHC II, cell surface markers characteristic for the differentiated myeloid cells macrophages and dendritic cells (Supplementary Figure). Although the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1int cells tended to be higher in WT compared to A2BKO mice, the difference between these subsets (22.6±1.3 vs. 19.4+1.3%, respectively; n=3) did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1C, D). To determine whether the lack of A2B receptors on hematopoietic or non-hematopoietic host cells is primarily responsible for a decrease in populations of CD11b+Gr-1high cells in LLC tumors, we generated bone marrow–chimeric mice and analyzed CD11b+Gr-1+ subpopulations of tumor-infiltrating CD45+ host immune cells. We found that the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1high was higher in chimeric wild-type mice given wild-type bone marrow compared to chimeric wild-type mice given A2BKO bone marrow (18.7±0.3 vs. 11.6±1.5%, respectively; P<0.01, n=3) and a similar difference was also observed between CD11b+Gr-1int subsets (25.2±0.7 vs. 17.4+0.5%, respectively; P<0.05, n=3). In contrast, the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1−/low cells was significantly lower in chimeric wild-type mice given wild-type bone marrow compared to chimeric wild-type mice given A2BKO bone marrow (45.6±0.4 vs. 57.3+1.4%, respectively; P<0.01, n=3) (Figure 1E, F). Taken together, these in vivo data imply that A2B adenosine receptors located on WT hematopoietic cells may promote the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells.

Figure 1. Ablation of A2B adenosine receptors reduces the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1high cells in the population of tumor-infiltrating host immune cells.

(A) Representative cytofluorographic dot plots showing the percentage of immune host cells (CD45+) in total tumor cell population. Single cell suspensions were prepared from tumors extracted from A2BKO and WT mice on day 14 after inoculation with LLC cells.

(B) Aggregate data from flow cytometry analysis of CD45+ cells obtained from 3 A2BKO and 3 WT animals. Values are expressed as mean±SEM; ns indicates non-significant difference (unpaired two-tail t-tests).

(C) Representative example of flow cytometry analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune host cells (gated for CD45) from A2BKO and WT mice using anti-CD11b and anti-Gr-1 antibodies.

(D) The percentage of CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets in the populations of tumor-infiltrating immune host cells from 3 A2BKO and 3 WT mice measured by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM; the asterisks indicate significant difference (* P<0.05, unpaired two-tail t-tests) and ns indicates non-significant difference, compared to corresponding A2BKO values.

(E) Representative example of flow cytometry analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune host cells from WT chimeric mice transplanted with A2BKO bone marrow cells (A2BKO→WT) and with WT bone marrow cells (WT→WT).

(F) The percentage of CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets in the populations of tumor-infiltrating immune host cells from 3 A2BKO→WT and 3 WT→WT bone marrow chimeric mice measured by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM; the asterisks indicate significant difference (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, unpaired two-tail t-tests), compared to corresponding A2BKO→WT values.

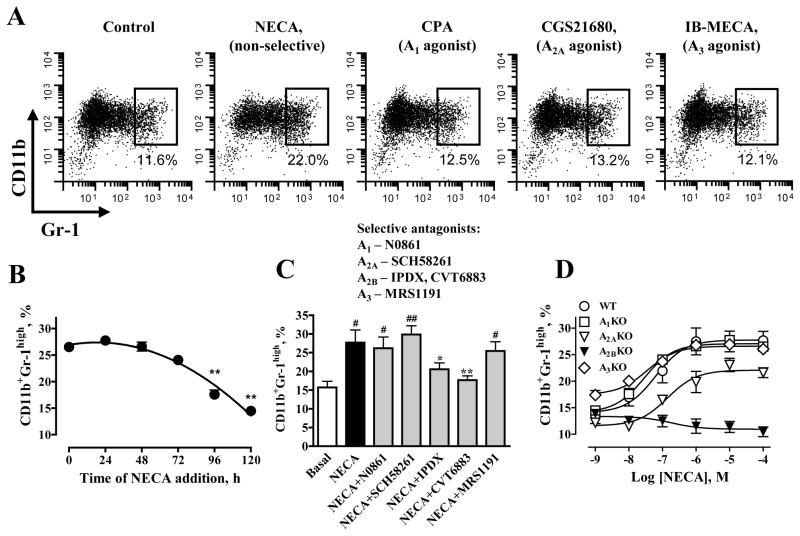

To test this hypothesis, we employed a previously established model of MDSC generation from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in vitro (23). Bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells isolated from WT mice were cultured for 5 days with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the absence or presence of adenosine receptor agonists. We stimulated all adenosine receptors with the non-selective adenosine receptor agonist NECA at a concentration of 10 μM. We specifically stimulated A1 receptors with CPA, A2A receptors with CGS21680 and A3 with IB-MECA at their selective concentrations (30) of 100 nM, 1 μM and 1 μM, respectively. As seen in Fgure 2A, only the non-selective adenosine receptor agonist NECA, but not the selective A1, A2A or A3 agonists promoted the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells. Because there was no significant difference between total numbers of MDSCs generated in the absence and presence of NECA (1.45±0.24 and 1.42±0.14 × 106 cells, respectively; P=0.9, n=8), an increase in the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1high cells in the presence of NECA corresponded to an increase in absolute CD11b+Gr-1high cell numbers. There was no significant difference between CD11b+Gr-1high subsets in MDSC populations generated in the presence of NECA added either at the beginning or up to 72 hours after starting the culture of hematopoietic progenitors with GM-CSF and IL-4. However, addition of NECA at later time points resulted in significant decrease in generated CD11b+Gr-1high MDSCs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors promotes expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells in vitro.

(A) Cytofluorographic dot plots of MDSCs generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in the presence of the non-selective agonist NECA or selective concentrations of receptor-specific agonists. Representative results of three experiments are shown. NECA, but not the selective agonists to A1, A2A, and A3 adenosine receptors increased the proportion of CD11b+Gr-1high cell subpopulation.

(B) Effect of addition of NECA (1 μM) at different time points during generation of MDSCs (starting in the absence of NECA) on the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1high cells assessed by flow cytometry on day 5. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3. Asterisks indicate significant difference (** P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s postest), compared to the value obtained with NECA added at the beginning of MDSC generation (time 0).

(C) Selective antagonists at the A2B receptor (IPDX and CVT-6883) but not selective antagonists at A1, A2A, and A3 adenosine receptors (N0861, SCH58261, and MRS1191, respectively) inhibit NECA-induced expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high subset. MDSCs were generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in the absence (Basal) or presence of 1 μM NECA and antagonists at their selective concentrations as indicated in Results. The proportion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells was measured by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3. Asterisks indicate significant difference (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s postest), compared to NECA, and pounds indicate significant difference (# P<0.05, ## P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s postest), compared to basal values.

(D) NECA-induced expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high subset is not reproduced only in cells from A2BKO animals. MDSCs were generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors obtained from A1, A2A, A2B, A3 adenosine receptor KO or WT mice in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of NECA. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3.

Further pharmacological analysis showed that only selective concentrations of A2B antagonists IPDX (10 μM) and CVT-6883 (100 nM) but not those of A1, A2A or A3 antagonists (1 μM N0861, 100 nM SCH58261 or 1 μM MRS1191, respectively) (30) inhibited the NECA-induced expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cell population (Figure 2C). Finally, NECA promoted CD11b+Gr-1high cell expansion in cultures of WT bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells with an estimated EC50 value of 62 nM (-logEC50 = 7.21±0.28; Figure 2D). NECA also potently promoted CD11b+Gr-1high cell expansion in cultures of cells isolated from mice deficient in A1, A2A and A3 receptors, but not in A2B receptors (Figure 2D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that A2B receptors are responsible for the observed adenosine-dependent expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells.

Stimulation of adenosine receptors promotes preferential expansion of the granulocytic subpopulation of CD11b+Gr-1high cells

CD11b+Gr-1low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets have been previously described in mouse bone marrow-derived MDSCs (31,32). We evaluated how these subpopulations are affected in cells generated in the presence of 1 μM NECA. Although we found no difference in total cell numbers between cells cultured in the absence and presence of NECA, the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1−/low cells was significantly decreased from 56.5±2.5 to 42.3±3.6%, whereas the percentage of CD11b+Gr-1high cells was significantly increased from 14.0±1.0 to 26.6±2.5% in cells generated in the presence of NECA, compared to control cells. No significant difference in CD11b+Gr-1int subsets was found between cells generated in the absence and presence of NECA (Figure 3A, B). Morphological evaluation of these subsets showed that CD11b+Gr-1−/low subset was composed by mononuclear cells, CD11b+Gr-1int subset presented a heterogeneous pattern comprising cells with monocyte-like and polymorphonuclear-like morphology, and CD11b+Gr-1high subset was represented by cells with mainly polymorphonuclear-like morphology. No substantial morphological difference was found between cells generated in the absence and presence of NECA (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Adenosine receptors promote preferential expansion of granulocytic MDSCs characterized by CD11b+Gr-1high/Ly-6Clow Ly-6Ghigh phenotype.

MDSCs were generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 μM NECA.

(A) Representative example of flow cytometry analysis using anti-CD11b and anti-Gr-1 antibodies.

(B) The percentage of CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets generated in the absence or presence of NECA measured by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=8. Asterisks indicate significant difference (** P<0.01, unpaired two-tail t-tests) and ns indicates non-significant difference, compared to control.

(C) Staining with Diff-Quik to evaluate subset morphology. CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets were generated in the absence or presence of 1 μM NECA and sorted by flow cytometry.

(D) Representative example of flow cytometry analysis using anti-Ly-6C and anti-Ly-6G antibodies.

(E) The percentage of Ly-6ChighLy-6Glow and Ly-6ClowLy-6Ghigh subsets generated in the absence or presence of NECA measured by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3. Asterisks indicate significant difference (** P<0.01, unpaired two-tail t-tests) and ns indicates non-significant difference, compared to control.

Because CD11+Ly-6ChighLy-6Glow and CD11+Ly-6ClowLy-6Ghigh MDSC subpopulations have been previously shown to closely match CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets, respectively (23,26), we used anti-Ly-6C and anti-Ly-6G antibodies as a complementary approach to differentiate between MDSC subsets. Again, we determined that the percentage of CD11+Ly-6ClowLy-6Ghigh cells was significantly increased, from 12.0±0.6 to 24.3±1.8%, in the cell population generated in the presence of NECA, compared to control cells, whereas no significant difference between CD11+Ly-6ChighLy-6Glow subsets was found (Figure 3D, E). Taken together, our results suggest that stimulation of A2B receptors promotes preferential expansion of the granulocytic subpopulation of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells.

A2B receptor-mediated expansion of granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high cells does not change their ROS production or Arg1 and iNOS expression

Previous studies suggested that the suppressive activity of MDSCs is associated with the production of ROS and with the expression of Arg1 and iNOS (23,26,28). Therefore, we compared the expression of these genes in subpopulations of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells generated in the absence or presence of 1 μM NECA (Figure 4A, B). We found that CD11b+Gr-1−/low cells expressed the highest levels of Arg1 and iNOS transcripts, compared to CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets. The only statistical significant difference was an increase in Arg1 expression in CD11b+Gr-1−/low cells generated in the presence of NECA compared to control, but not in CD11b+Gr-1int or CD11b+Gr-1high subsets (Figure 4A). We also observed a 3-fold increase in iNOS expression in CD11b+Gr-1high cells generated in the presence of NECA compared to control (Figure 4B). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07, n=4) possibly due to the low expression of iNOS in these subsets, hence, the higher amount of intra-sample variability.

Figure 4. Production of reactive oxygen species in MDSC subsets and the expression of enzymes relevant to their suppressive activity.

(A) MDSCs were generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 μM NECA. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of Arg 1 mRNA was performed in CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets isolated by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3. The asterisk indicates significant difference (* P<0.05, unpaired two-tail t-tests) and ns indicates non-significant difference, compared to control.

(B) MDSCs were generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 μM NECA. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of iNOS mRNA was performed in CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets isolated by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=4; ns indicates non-significant difference, compared to control.

(C) ROS production in CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets at rest or after stimulation with 100 nM PMA was evaluated as described in Methods. Values represent a difference between mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) of cells stained with the oxidation-sensitive dye CM-H2DCFDA and unstained control. Values are expressed as average of two determinations.

(D) Effect of increasing concentrations of PMA on ROS production in CD11b+Gr-1high subsets of MDSCs generated in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 μM NECA. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3.

In contrast to their low expression of Arg1 and iNOS, CD11b+Gr-1high subsets are characterized by the highest levels of ROS production in response to stimulation with 100 nM PMA (Figure 4C). However, we found no difference in PMA-induced ROS generation between CD11b+Gr-1high subsets of cells generated in the absence and presence of NECA (Figure 4D). Thus, we concluded that A2B receptor-mediated expansion of granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high cells does not change their ability to produce ROS or their expression of Arg1 and iNOS.

Granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high cells are characterized by high levels of ecto-5′-nucletidase activity

Recent evidence suggests that ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) is expressed at high levels on the regulatory T lymphocyte subset (Tregs) and plays an important role in their immunosuppressive properties by generating extracellular adenosine, which then suppresses effector T cell responses via A2A adenosine receptors (10–12). This mechanism, however, has not been explored in nonlymphoid suppressor cells. Therefore, we next analyzed the expression of CD73 in CD11b+Gr-1+ cell subpopulations using flow cytometry. We found that the CD11b+Gr-1high subset had the highest levels of CD73 expression (ΔMFI of 118.5±16.8), followed by CD11b+Gr-1int (ΔMFI of 57.9±6.8) and CD11b+Gr-1−/low (ΔMFI of 12.4±1.0). Even lower levels of CD73 expression were found on LLC tumor cells (ΔMFI of 3.2±0.2; Figure 5A, B).

Figure 5. Granulocytic MDSCs express high levels of functional ecto-5′-nucleotidase.

(A) Representative flow cytometry histograms of CD73 expression on the surface of LLC tumor cells and CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets of MDSCs generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors.

(B) Graphic representation of data from flow cytometry analysis of CD73 expression on the surface of LLC tumor cells and CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets of MDSCs generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=4. Asterisks indicate significant difference (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s postest) between subsets.

(C) Enzymatic activity of ecto-5′-nucleotidase expressed on CD11b+Gr-1−/low, CD11b+Gr-1int and CD11b+Gr-1high subsets of MDSCs generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 μM NECA (NECA-treated). Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3.

(D) Effect of ecto-5′-nucleotidase inhibition with APCP on AMP-induced expansion of granulocytic MDSCs. The percentage of CD11b+Gr-1high cells generated in the absence (Basal, APCP) or presence of 100 μM AMP (AMP, AMP+APCP) and in the absence (AMP, Basal) or presence of 100 μM APCP (AMP+APCP, APCP) was measured by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3. Asterisks indicate significant differences (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s postest) and ns indicates non-significant difference between values.

The high levels of CD73 expression correlated with high levels of ecto-5′-nucletidase enzymatic activity in granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high cells. No significant differences in ecto-5′-nucletidase activities were found between cells generated in the absence and presence of NECA (Figure 5C). To determine if adenosine produced as a result of ecto-5′-nucletidase activity could contribute to the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells, we generated MDSCs in the presence of the ecto-5′-nucletidase substrate AMP. As seen in Figure 5D, 100 μM AMP significantly increased the population of generated CD11b+Gr-1high MDSCs and this effect was inhibited by the ecto-5′-nucletidase inhibitor APCP (100 μM).

Ecto-5′-nucletidase activity potentiates the immunosuppressive properties of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells

To determine if CD73 highly expressed on granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1+ cells could contribute to their immunosuppressive properties, we initially used a previously published method of enrichment of granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high cells by immunomagnetic sorting with anti-Ly-6G antibody (26). These cells were then co-cultured at different proportions with T cells stimulated with anti-CD3–anti-CD28–coupled microbeads in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of the ecto-5′-nucletidase substrate AMP. In the absence of AMP, inhibition of T cell proliferation by Ly-6G+ cells was observed only at their highest concentration of 12%, but not at 6 or 3%. With increasing concentrations of AMP, however, even 3% Ly-6G+ cells became capable of inhibiting T cell proliferation (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity facilitates the suppression of T cell proliferation by granulocytic MDSCs.

(A) MDSCs were generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors and CD11b+Gr-1high cells were enriched (>70%) by positive immunomagnetic selection with anti-Ly-6G antibody. T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3–anti-CD28–coupled microbeads and cultured without (0) or co-cultured together with CD11b+Gr-1high cells added at numbers corresponding to 3, 6 or 12% of T cell numbers in the presence of increasing concentrations of 5′-AMP. Values are expressed as mean±SEM, n=3.

(B) MDSCs were generated from mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 μM NECA (NECA-treated) and CD11b+Gr-1high cells were purified (>95%) by flow cytometry. T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3–anti-CD28–coupled microbeads and cultured without (0) or co-cultured together with CD11b+Gr-1high cells added at numbers corresponding to 6 or 12% of T cell numbers in the absence (Control, NECA-treated) or presence of 300 μM 5′-AMP (Control+AMP, NECA-treated+AMP). Data are presented as mean±SEM (n=3) of maximal thymidine incorporation.

In complementary set of experiments, granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high subsets were isolated directly by flow cytometry sorting from cells generated in the absence or presence of NECA. CD11b+Gr-1high subsets were co-cultured with T cells in the absence or presence of AMP. Figure 6B shows that AMP facilitated the suppression of T cell proliferation by either CD11b+Gr-1high subsets isolated from cells generated in the absence or presence of NECA. Taken together, these results suggest that ecto-5′-nucletidase activity of CD73 can potentiate the immunosuppressive properties of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells.

DISCUSSION

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells were initially described as natural suppressor cells without lymphocyte-lineage markers that could suppress lymphocyte response to immunogens and mitogens (33). The population of these cells is expanded in various pathologic conditions, including infections, inflammatory diseases, trauma and neoplastic diseases, presumably with the purpose of limiting T cell responses (15–17). Various factors produced in these conditions, including growth factors and inflammatory cytokines, have been proposed to induce the expansion of MDSCs (reviewed in (15)). Adenosine and purine nucleotides are released into the interstitium under conditions of hypoxia, cell stress or injury (18), and become part of the microenvironment in most if not all the conditions associated with MDSC accumulation. Therefore, we hypothesized that adenosinergic pathways play a role in MDSC accumulation and functions.

In this study, we reproduced a previously described LLC isograft tumor model in A2BKO and WT mice (22) and analyzed the expression of myeloid cell surface markers CD11b and Gr-1 characteristic for MDSCs in the population of tumor-infiltrating CD45+ immune cells. We observed significantly lower frequency of CD11b+Gr-1high cells in LLC tumors growing in A2BKO mice compared to WT control, indicating that A2B adenosine receptors may play a role in accumulation of CD11b+Gr-1high cells in LLC tumors in vivo. Importantly, the proportion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells was also lower in LLC tumors growing in WT chimeric mice with transplanted A2BKO bone marrow compared to WT mice given WT bone marrow, suggesting that A2B adenosine receptors located on hematopoietic cells may regulate the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells.

Indeed, our in vitro studies demonstrated that A2B receptors promote preferential expansion of granulocytic (CD11b+Gr-1high/Ly-6G+Ly-6Clow) subpopulations of MDSCs. Using genetic and pharmacological approaches we determined that the A2B receptor, but not the other adenosine receptor subtypes can promote the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells generated from bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in vitro. Several lines of evidence support our conclusion. First, only the nonselective adenosine receptor agonist NECA, but not agonists at other adenosine receptor subtypes promoted the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells. Second, this effect was inhibited by selective A2B antagonists, but not by selective antagonists at other adenosine receptor subtypes. Finally, NECA had no effect in cell cultures derived from A2BKO mice but potently promoted the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1high cells lacking any other adenosine receptor subtype.

Analysis of MDSC fractions generated in the absence or presence of NECA demonstrated that stimulation of A2B receptors favored accumulation of granulocytic MDSCs at the expense of monocytic MDSCs. In agreement with previous reports (26,28), Gr-1/Ly-6G brightness positively correlated with polymorphonuclear-like morphology, and negatively with monocyte-like morphology. Preferential expansion of granulocytic MDSCs is often observed in various tumor models (23) and our study demonstrated that stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors promoted preferential expansion of MDSCs with granulocytic CD11b+Gr-1high/Ly-6G+Ly-6Clow phenotype. Because extracellular levels of adenosine have been shown to increase during tumor growth (34,35), it is possible that this adenosinergic mechanism contribute to the tumor-associated expansion of granulocytic MDSCs.

We found that granulocytic MDSCs generated in the presence of NECA were morphologically similar to those generated in the absence of NECA. Furthermore, we found no difference in their ability to generate ROS, a putative mediator of their immunosupressive properties (23). The suppressive activity of MDSCs has been also associated with the metabolism of L-arginine (36). This amino acid serves as a substrate for two enzymes, iNOS (which generates NO) and arginase 1 (which converts L-arginine to urea and L-ornithine). In agreement with previous reports (26), we found that the expression of these enzymes was negatively correlated with Gr-1 brightness. Moreover, no significant difference in the expression of Arg1 and iNOS genes was seen between granulocytic MDSCs generated in the presence and absence of NECA.

The role of granulocytic MDSCs in the regulation of immune responses has long been a subject of controversy; even though the expansion of granulocytic MDSCs has been documented at many pathological conditions, their suppressive activity is only moderate in conventional in vitro assays (23,26,28,29). One possible explanation is that these in vitro conditions do not reflect the pathological microenvironment generated by the same disease processes that lead to the expansion of MDSCs, with accumulation of factors that induce their immunosuppressive activity (15). Purine nucleotides including AMP are known to accumulate in the interstitium following cell stress/damage (18) and may constitute such factors. An important novel aspect of our studies, therefore, is the demonstration of the very high levels of CD73 expression in granulocytic MDSCs. We found that the expression of CD73 and ecto-5′-nucletidase enzymatic activities in MDSC subsets are positively correlated with Gr-1 brightness. This finding may help us understand the biological significance of the A2B receptor-dependent expansion of granulocytic MDSCs. The role of CD73 in these conditions becomes very important; our study demonstrated that in vitro ability of granulocytic MDSCs to suppress CD3/CD28-induced T cell proliferation is significantly facilitated in the presence of the ecto-5′-nucletidase substrate AMP.

Thus, our study indicated that generation of adenosine by CD73 may be a novel mechanism of immunosuppression by granulocytic MDSCs. In this study we focused specifically on the expression of CD73 given its key role as the pacemaker of adenosine generation from adenine nucleotides (37). Tumor cells including LLC release high levels of ATP (38). High extracellular ATP concentrations in the hundreds micromolar range were detected in tumor sites in vivo (39). Generation of adenosine from ATP depends also on the ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase activity of CD39. Myeloid cells are known to express CD39 (40) and we detected the expression of this marker on the surface of MDSCs (data not shown). It would be interesting to determine whether the enzymatic activity of CD39 on MDSCs is sufficient to efficiently generate adenosine from ATP, or they would require partner cells with higher ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase activity on their surface.

Immunosuppressive activities of adenosine have been long recognized (2,3), and multiple studies attributed these properties mainly to inhibition of T cell responses via A2A adenosine receptors (4–9). In fact, a similar mechanism involving adenosine generation by CD73 has been initially demonstrated in CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T lymphocytes (10–12). Furthermore, recent studies suggested that tumors expressing high levels of CD73 may use this adenosinergic mechanism to induce tumor imuunotolerance via A2A adenosine receptor-mediated suppression of T cell responses (14). However, contribution of cancer cells would be minimal in our model because we found very low levels of CD73 expression on LLC tumor cells compared to those in granulocytic MDSCs. That CD73 expression on host cells is crucial for protection of tumors from host immunosurveillance was recently demonstrated in other tumor models generated in CD73 gene-targeted mice; CD73 ablation in hosts significantly suppressed the growth of MC38 colon cancer, EG7 lymphoma, AT-3 mammary tumors and B16F10 melanoma (13).

Based on the previously described adenosine effects on T cell functions (4–9) and our new data obtained in this study, we propose a model of adenosineric regulation of immune responses by MDSCs (Figure 7). According to this model, generation of adenosine by CD73 expressed at high levels on granulocytic MDSCs will have a dual effect both on their expansion and suppressive activity. Acting on A2A receptors, adenosine will suppress the activity of T cells (4–9), thus contributing to the MDSC properties to limit immune responses. Acting on A2B receptors of myeloid precursors, adenosine will promote the expansion of granulocytic MDSCs, a subset with the highest levels of CD73 expression. This positive feedback mechanism would facilitate further generation of adenosine and enhanced immunosupression, until cell stress/damage in the affected area is ameliorated and the levels of interstitial purine nucleotides return to normal.

Figure 7. Model of adenosineric regulation of MDSC expansion and function.

Generation of adenosine by ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) expressed at high levels on granulocytic MDSCs (CD11b+Gr-1high) may promote their expansion by stimulation of A2B receptors on myeloid progenitors (MPs) and facilitate their suppressive activity by acting on A2A receptors of T cells, thus limiting immune response.

Although our current study focused primarily on MDSCs, the role of adenosine in the regulation of differentiation and functions of other myeloid cells, e.g. macrophages and dendritic cells has been described (21,41–45). Our new data contribute to the growing evidence that adenosine serves as an important immunomodulating molecule. The proposed model identifies the A2B receptor as a critical modulator of myeloid cell differentiation and the CD73/adenosine A2 receptor axis as a potential therapeutic target to overcome immunosupression if necessary, e.g. to enhance efficacy of cancer vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Luiz Belardinelli, Dewan Zeng, and Hongyan Zhong (Gilead Palo Alto, Inc) for scientific discussion. We also thank Dr. Jürgen Schnermann, (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for providing A1KO mice, Dr. Jiang-Fan Chen (Boston University, Boston, MA) for providing A2AKO mice and Dr. Marlene Jacobson (Merck Research Laboratories, West Point, PA) for providing A3KO mice.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01HL095787 (I. Feoktistov), R01CA138923 (M.M. Dikov and I. Feoktistov).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- A1KO

A1 adenosine receptor knockout

- A2AKO

A2A adenosine receptor knockout

- A2BKO

A2B adenosine receptor knockout

- A3KO

A3 adenosine receptor knockout

- Arg1

arginase 1

- APCP

adenosine 5′-(α,β-methylene) diphosphate

- CPA

N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IPDX

3-isobutyl-8-pyrrolidinoxanthine

- LLC

Lewis lung carcinoma

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- WT

wild type

References

- 1.Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirschhorn R, Grossman J, Weissmann G. Effect of cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate and theophylline on lymphocyte transformation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1970;133:1361–1365. doi: 10.3181/00379727-133-34690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hovi T, Smyth JF, Allison AC, Williams SC. Role of adenosine deaminase in lymphocyte proliferation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1976;23:395–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang S, Apasov S, Koshiba M, Sitkovsky M. Role of A2a extracellular adenosine receptor-mediated signaling in adenosine-mediated inhibition of T-cell activation and expansion. Blood. 1997;90:1600–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koshiba M, Kojima H, Huang S, Apasov S, Sitkovsky MV. Memory of extracellular adenosine A2A purinergic receptor-mediated signaling in murine T cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25881–25889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohta A, Gorelik E, Prasad SJ, Ronchese F, Lukashev D, Wong MK, Huang X, Caldwell S, Liu K, Smith P, Chen JF, Jackson EK, Apasov S, Abrams S, Sitkovsky M. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koshiba M, Rosin DL, Hayashi N, Linden J, Sitkovsky MV. Patterns of A2A extracellular adenosine receptor expression in different functional subsets of human peripheral T cells. Flow cytometry studies with anti-A2A receptor monoclonal antibodies. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lappas CM, Rieger JM, Linden J. A2A adenosine receptor induction inhibits IFN-gamma production in murine CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:1073–1080. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naganuma M, Wiznerowicz EB, Lappas CM, Linden J, Worthington MT, Ernst PB. Cutting edge: Critical role for A2A adenosine receptors in the T cell-mediated regulation of colitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:2765–2769. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobie JJ, Shah PR, Yang L, Rebhahn JA, Fowell DJ, Mosmann TR. T regulatory and primed uncommitted CD4 T cells express CD73, which suppresses effector CD4 T cells by converting 5′-adenosine monophosphate to adenosine. J Immunol. 2006;177:6780–6786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, Friedman D, Usheva A, Erat A, Chen JF, Enjyoji K, Linden J, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK, Strom TB, Robson SC. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandapathil M, Hilldorfer B, Szczepanski MJ, Czystowska M, Szajnik M, Ren J, Lang S, Jackson EK, Gorelik E, Whiteside TL. Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7176–7186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stagg J, Divisekera U, Duret H, Sparwasser T, Teng MW, Darcy PK, Smyth MJ. CD73-deficient mice have increased anti-tumor immunity and are resistant to experimental metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2892–2900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin D, Fan J, Wang L, Thompson LF, Liu A, Daniel BJ, Shin T, Curiel TJ, Zhang B. CD73 on tumor cells impairs antitumor T-cell responses: a novel mechanism of tumor-induced immune suppression. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2245–2255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peranzoni E, Zilio S, Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Zanovello P, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell heterogeneity and subset definition. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnstock G. Pathophysiology and therapeutic potential of purinergic signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:58–86. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredholm BB, Irenius E, Kull B, Schulte G. Comparison of the potency of adenosine as an agonist at human adenosine receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasko G, Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Vizi ES, Pacher P. A2B adenosine receptors in immunity and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novitskiy SV, Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Huang Y, Tikhomirov OY, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, Carbone DP, Feoktistov I, Dikov MM. Adenosine receptors in regulation of dendritic cell differentiation and function. Blood. 2008;112:1822–1831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-136325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryzhov S, Novitskiy SV, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Carbone DP, Biaggioni I, Dikov MM, Feoktistov I. Host A2B adenosine receptors promote carcinoma growth. Neoplasia (New York) 2008;10:987–995. doi: 10.1593/neo.08478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feoktistov I, Garland E, Goldstein AE, Zeng D, Belardinelli L, Wells JN, Biaggioni I. Inhibition of human mast cell activation with the novel selective adenosine A2B receptor antagonist 3-isobutyl-8-pyrrolidinoxanthine (IPDX) Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Novitskiy SV, Dikov MM, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. Effect of A2B adenosine receptor gene ablation on proinflammatory adenosine signaling in mast cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:7212–7220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Ugel S, Marigo I, Fernandez GA, Mesa C, Geilich M, Winkels G, Traggiai E, Casati A, Grassi F, Bronte V. Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:22–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baykov AA, Evtushenko OA, Avaeva SM. A malachite green procedure for orthophosphate determination and its use in alkaline phosphatase-based enzyme immunoassay. Anal Biochem. 1988;171:266–270. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, De BP, Van Ginderachter JA. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haile LA, Gamrekelashvili J, Manns MP, Korangy F, Greten TF. CD49d is a new marker for distinct myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations in mice. J Immunol. 2010;185:203–210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryzhov S, Solenkova NV, Goldstein AE, Lamparter M, Fleenor T, Young PP, Greelish JP, Byrne JG, Vaughan DE, Biaggioni I, Hatzopoulos AK, Feoktistov I. Adenosine receptor-mediated adhesion of endothelial progenitors to cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:356–363. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nefedova Y, Huang M, Kusmartsev S, Bhattacharya R, Cheng P, Salup R, Jove R, Gabrilovich D. Hyperactivation of STAT3 is involved in abnormal differentiation of dendritic cells in cancer. J Immunol. 2004;172:464–474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, Mesa C, Fernandez A, Dolcetti L, Ugel S, Sonda N, Bicciato S, Falisi E, Calabrese F, Basso G, Zanovello P, Cozzi E, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strober S. Natural suppressor (NS) cells, neonatal tolerance, and total lymphoid irradiation: exploring obscure relationships. Annu Rev Immunol. 1984;2:219–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blay J, White TD, Hoskin DW. The extracellular fluid of solid carcinomas contains immunosuppressive concentrations of adenosine. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2602–2605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raskovalova T, Huang X, Sitkovsky M, Zacharia LC, Jackson EK, Gorelik E. Gs protein-coupled adenosine receptor signaling and lytic function of activated NK cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:4383–4391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Van De Wiele CJ, Resta R, Morote-Garcia JC, Colgan SP. Crucial role for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1395–1405. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita M, Andoh T, Sasaki A, Saiki I, Kuraishi Y. Involvement of peripheral adenosine 5′-triphosphate and P2X purinoceptor in pain-related behavior produced by orthotopic melanoma inoculation in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1629–1636. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pellegatti P, Raffaghello L, Bianchi G, Piccardi F, Pistoia V, Di VF. Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koziak K, Sevigny J, Robson SC, Siegel JB, Kaczmarek E. Analysis of CD39/ATP diphosphohydrolase (ATPDase) expression in endothelial cells, platelets and leukocytes. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1538–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinhal-Enfield G, Ramanathan M, Hasko G, Vogel SN, Salzman AL, Boons GJ, Leibovich SJ. An angiogenic switch in macrophages involving synergy between Toll-like receptors 2, 4, 7, and 9 and adenosine A2A receptors. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:711–721. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63698-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Virag L, Gergely P, Leibovich SJ, Pacher P, Sun CX, Blackburn MR, Vizi ES, Deitch EA, Hasko G. A2A adenosine receptors and C/EBPbeta are crucially required for IL-10 production by macrophages exposed to Escherichia coli. Blood. 2007;110:2685–2695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Novitskiy SV, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. Effect of A2B adenosine receptor gene ablation on adenosine-dependent regulation of proinflammatory cytokines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:694–700. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben AA, Lefort A, Hua X, Libert F, Communi D, Ledent C, Macours P, Tilley SL, Boeynaems JM, Robaye B. Modulation of murine dendritic cell function by adenine nucleotides and adenosine: involvement of the A2B receptor. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1610–1620. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson JM, Ross WG, Agbai ON, Frazier R, Figler RA, Rieger J, Linden J, Ernst PB. The A2B adenosine receptor impairs the maturation and immunogenicity of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:4616–4623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.