Abstract

Introduction

Although inhalation of 80 parts per million (ppm) of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) reduces metabolism in mice, doses higher than 200 ppm of H2S were required to depress metabolism in rats. We therefore hypothesized that higher concentrations of H2S are required to reduce metabolism in larger mammals and humans. To avoid the potential pulmonary toxicity of H2S inhalation at high concentrations, we investigated whether administering H2S via ventilation of an extracorporeal membrane lung (ECML) would provide means to manipulate the metabolic rate in sheep.

Methods

A partial venoarterial cardiopulmonary bypass was established in anesthetized, ventilated (fraction of inspired oxygen = 0.5) sheep. The ECML was alternately ventilated with air or air containing 100, 200, or 300 ppm H2S for intervals of 1 hour. Metabolic rate was estimated on the basis of total CO2 production () and O2 consumption (). Continuous hemodynamic monitoring was performed via indwelling femoral and pulmonary artery catheters.

Results

, , and cardiac output ranged within normal physiological limits when the ECML was ventilated with air and did not change after administration of up to 300 ppm H2S. Administration of 100, 200 and 300 ppm H2S increased pulmonary vascular resistance by 46, 52 and 141 dyn·s/cm5, respectively (all P ≤ 0.05 for air vs. 100, 200 and 300 ppm H2S, respectively), and mean pulmonary artery pressure by 4 mmHg (P ≤ 0.05), 3 mmHg (n.s.) and 11 mmHg (P ≤ 0.05), respectively, without changing pulmonary capillary wedge pressure or cardiac output. Exposure to 300 ppm H2S decreased systemic vascular resistance from 1,561 ± 553 to 870 ± 138 dyn·s/cm5 (P ≤ 0.05) and mean arterial pressure from 121 ± 15 mmHg to 66 ± 11 mmHg (P ≤ 0.05). In addition, exposure to 300 ppm H2S impaired arterial oxygenation (PaO2 114 ± 36 mmHg with air vs. 83 ± 23 mmHg with H2S; P ≤ 0.05).

Conclusions

Administration of up to 300 ppm H2S via ventilation of an extracorporeal membrane lung does not reduce and , but causes dose-dependent pulmonary vasoconstriction and systemic vasodilation. These results suggest that administration of high concentrations of H2S in venoarterial cardiopulmonary bypass circulation does not reduce metabolism in anesthetized sheep but confers systemic and pulmonary vasomotor effects.

Introduction

Balancing cellular oxygen supply and demand is a key therapeutic approach to protecting organs such as the brain, kidneys and heart from ischemic injury. Permissive hypothermia and active cooling have been shown to reduce oxygen demands in patients experiencing stroke, cardiac arrest, cardiac surgery, severe trauma and other instances of ischemia and subsequent reperfusion [1-4]. However, hypothermic reduction of aerobic metabolism has been associated with adverse effects, including increased rates of infection and coagulopathy [5,6]. Developing other methods to acutely reduce metabolism in patients could be clinically useful.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an inhibitor of cytochrome C oxidase in the mitochondrial electron transport chain [7] that reduces metabolism and body temperature in mice and rats [8,9]. Inhalation of H2S or intravenous administration of H2S donor compounds (NaHS or Na2S) can protect rodents from hypoxia [10] or hemorrhagic shock [11], improve survival rates after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in mice [12], and attenuate myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in both rodents [13] and pigs [14].

Although inhaling H2S at 60 to 80 ppm reduces metabolism in mice, it has been reported that inhaled H2S does not depress total CO2 production () and total O2 consumption () in sedated, spontaneously breathing sheep (60 ppm H2S) [15] or anesthetized, ventilated piglets (20 to 80 ppm H2S) [16]. On the other hand, Struve et al. [8] reported that inhalation of H2S at 200 to 400 ppm, but not at 30 to 80 ppm, decreased body temperature in rats. Similarly, Morrison et al. [11] showed that inhaling H2S at 300 ppm was required to decrease in rats, in contrast to 80 ppm in mice. While these observations suggest that higher levels of H2S are likely to be required to alter metabolic rates in larger animals [11], the effects of higher concentrations of H2S on metabolism in larger mammals have not been examined.

It is well documented, however, that inhalation of high concentrations of H2S may injure the bronchial mucosa, cause pulmonary edema, and impair gas exchange [17,18]. To examine the impact of delivering higher concentrations of H2S to the body without incurring the pulmonary toxicity of H2S inhalation, we administered H2S gas via an extracorporeal membrane lung (ECML). We hypothesized that high concentrations of H2S delivered via ECML in a partial venoarterial bypass system delivering blood to the aortic root might reduce the metabolic rate in sheep at rest. If ECML ventilation with H2S was found to reduce the metabolic rate in sheep, this method might provide a novel approach to balance the supply and demand of oxygen in a variety of situations, including in those patients who are supported by extracorporeal circulation during cardiac surgery or severe acute respiratory distress.

Materials and methods

All procedures described here were approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Recommendations for the Care and Use of Animals.

Animal housing and maintenance

Five female purebred Polypay sheep (body weight: 30.6 ± 2.5 kg, mean ± SD) were obtained from a single-source breeder (New England Ovis LLC, Rollinsford, NH, USA) and were housed under standard environmental conditions (air-conditioned room at 22°C, 50% relative humidity, 12-hour light-dark cycle) for at least 5 days prior to each study. Animals were fed standard chow (Rumilab diet 5508; PMI Feeds Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) twice daily and were fasted for 24 hours with free access to water before each experiment.

Instrumentation

After intramuscular premedication with 5 mg/kg ketamine (ketamine hydrochloride; Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) and 0.1 mg/kg xylazine (Anased; Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA, USA), a venous cannula (Surflo IV catheter 18G; Terumo, Elkton, MD, USA) was inserted into an ear vein and a bolus of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg diazepam (Diazepam USP; Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) administered intravenously (iv). Subsequently, the animals were placed in a supine position and were intubated and mechanically ventilated with a volume-controlled mode (fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) 50%, tidal volume 10 ml/kg) (7200 Series Ventilator System; Puritan Bennett, Boulder, CO, USA). Anesthesia was maintained by a constant rate infusion of ketamine at 3 mg∙kg-1∙h-1 and diazepam at 0.5 mg∙kg-1∙h-1. Respiratory rate was adjusted to maintain the end-tidal CO2 between 35 and 40 mmHg. An arterial catheter (18G, FA-04018; Arrow Inc., Reading, PA, USA) was placed into the right femoral artery via percutaneous puncture to monitor mean arterial pressure (MAP) and to sample blood. Subsequently, an 8-Fr heptalumen pulmonary artery catheter (746HF8; Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was introduced through a percutaneous sheath (9 Fr, PB-09903; Arrow Inc., Reading, PA, USA) into the left external jugular vein for blood sampling and monitoring of mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP), central venous pressure (CVP), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), continuous cardiac output (CO) and blood temperature. Finally, a transurethral bladder catheter and a transesophageal gastric tube were inserted to drain urine and gastric secretions. During the first hour after induction, animals received an infusion of 500 ml of 6% hetastarch (Hextend; Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) and 500 ml of lactated Ringer's solution (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA); thereafter, 16 ml∙kg-1∙h-1 of lactated Ringer's solution and 9 ml∙kg-1∙h-1 of 0.9% saline were infused to match fluid losses from diuresis and gastric secretions.

Extracorporeal circulation

A 20-Fr single-stage venous cannula (DLP; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and a 14-Fr arterial cannula (Fem-Flex II; Medtronic) were surgically inserted and advanced through the right external jugular vein and right common carotid artery, respectively, thereby enabling blood withdrawal from the superior vena cava and arterial blood return to the aortic root from the extracorporeal cardiopulmonary bypass circuit. The bypass circuit comprised a three-eighths-inch polyethylene tubing line (3506; Medtronic), an occlusive roller pump (Cardiovascular Instruments Corp., Wakefield, MA, USA) and an ECML (Trillium 541TT Affinity; Medtronic) with an integral heat exchanger, and it was primed with a total extracorporeal priming volume of 500 ml of 0.9% saline. A bolus injection of unfractionated heparin (200 IU/kg heparin sodium; APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Schaumburg, IL, USA) prior to cannulation, followed by a continuous infusion of 200 IU/kg unfractionated heparin per hour was used for anticoagulation. A thermostat-controlled water bath (Haake DC10-P5; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplying the heat exchanger with circulating water was maintained at 38°C. The gas compartment of the oxygenator was ventilated at a constant flow of 5 l/min with oxygen, air and H2S (10,000 ppm hydrogen sulfide balanced with nitrogen; Airgas Specialty Gases, Port Allen, LA, USA) blended to achieve an oxygen concentration of 21% with 0, 100, 200, or 300 ppm H2S.

A handheld iTX Multi-Gas detector (1 ppm detection threshold; Industrial Scientific, Oakdale, PA, USA) was used to monitor the H2S concentrations at the inlet and outlet of the gas compartment.

Experimental procedures

Once partial venoarterial bypass perfusion was started, the transmembrane blood flow was gradually increased to 1 l/min. Then the respiratory rate was reduced to maintain an end-tidal partial pressure of CO2 of 35 to 40 mmHg, and sheep were paralyzed (0.1 mg∙kg-1∙h-1 of pancuronium bromide iv; Sicor Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA, USA) to prevent spontaneous respiratory activity, asynchronous ventilation and excessive skeletal muscle O2 consumption. A 1-hour equilibration period was allowed to achieve hemodynamic stability before baseline measurements were taken.

During the following 6 hours, the ECML gas compartment was alternately ventilated with either air or air plus H2S for 1-hour intervals, thereby administering 0 ppm H2S during the first hour, 100 ppm H2S during the second hour, followed by 0 and 200 ppm during the third and fourth hours and finally 0 and 300 ppm H2S during the fifth and sixth hours. This procedure was chosen to detect the hemodynamic and metabolic effects of exposure to increasing H2S concentrations through the membrane lung, as well as their reversibility.

Measurements and monitoring

A digital data acquisition system (PowerLab and Chart software version 5.0; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) was used to continuously record MAP, CVP and MPAP. A Vigilance II Monitor (Edwards Lifesciences) was used to continuously measure CO and central blood temperature. End-tidal CO2, as well as the total amount of CO2 exhaled from the biological lungs per unit of time (), was measured by an in-stream, noninvasive, continuous monitoring device (NICO Cardiopulmonary Management System; Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA). Blood gas tensions, hemoglobin concentrations, and acid-base balances were determined in arterial and mixed venous blood samples using a standard blood gas analyzer (ABL 800 Flex; Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Plasma concentrations of H2S were measured in duplicate as total sulfide concentrations using the methylene blue formation method with modifications [19]. Briefly, arterial and ECML-efferent blood was sampled and immediately centrifuged at 4°C to obtain plasma. An aliquot of plasma (100 μl) was added with 2% zinc acetate (200 μl) to trap the H2S, and 10% trichloroacetic acid (200 μl) was added to precipitate plasma proteins, immediately followed by 20 mM N,N-dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine sulfate in 7.2 M HCl (100 μl) and 30 mM FeCl3 in 1.2 M HCl (100 μl). The reaction mixture was incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 670 nm using a spectrophotometer. Total sulfide concentration was calculated against a standard curve made with known concentrations of Na2S solutions in phosphate-buffered saline. The lower detection limit of this assay was approximately 1 μM sulfide in plasma.

Calculation of carbon dioxide production

Total was monitored continuously and was calculated as the sum of CO2 exhaled from the lungs per unit of time () and the amount of CO2 removed from the circulation via the membrane oxygenator (), according to the following equations:

| (1) |

where is the expiratory minute volume and FECO2 is the mean fraction of CO2 in expired air. Quantification of and FECO2 and the calculation of were accomplished by a continuous noninvasive NICO device (see 'Measurements and monitoring' section):

| (2) |

where Qgas is the total gas flow exhausted from the membrane oxygenator and FECO2 is the fraction of CO2 in the exhaust gas. Qgas was continuously monitored by a microturbine flow meter (S-113 Flo-Meter; McMillan Co., Georgetown, TX, USA), and FECO2 was measured by a sidestream infrared CO2 analyzer (WMA-4; PP-Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA).

Calculation of oxygen consumption

Total was calculated on the basis of blood samples drawn 10 minutes before the end of each period of exposure to air or H2S as follows:

| (3) |

where caO2 is the oxygen content of arterial blood, cvO2 is the oxygen content of mixed venous blood, QL is transpulmonary blood flow (here meaning continuous CO measured via pulmonary artery catheter), ceO2 is the oxygen content of ECML-efferent blood and QM is extrapulmonary blood flow (here meaning transmembrane blood flow). Blood oxygen content (cO2) was calculated according to the following general equation:

| (4) |

where [Hb] is the hemoglobin concentration, FO2Hb is the fraction of oxyhemoglobin, 1.34 is Hüfner's constant and pO2 is the oxygen tension.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 14.0 data package for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 5.02 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are reported as means ± SD unless indicated otherwise. Hemodynamic parameters, and body temperature were measured continuously and are reported as the mean value derived from the last 10 minutes of each period of exposure to air or H2S. In addition, hemodynamic parameters were averaged every 5 minutes for a time course analysis, and these data are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. Blood gas tension analysis, determination of blood hemoglobin concentrations and quantification of H2S plasma concentrations required blood sampling. Samples were obtained during the last 5 minutes of each period of exposure. Depending on the distribution of the data as determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test for normal distribution, either Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed to compare each H2S ventilation period with the respective baseline period (0 ppm H2S). Statistical significance was assumed at P ≤ 0.05. On the basis of data derived from pilot experiments, power and sample size calculations were performed using PS: Power and Sample Size Calculation version 2.1.31 software by Dupont and Plummer [20].

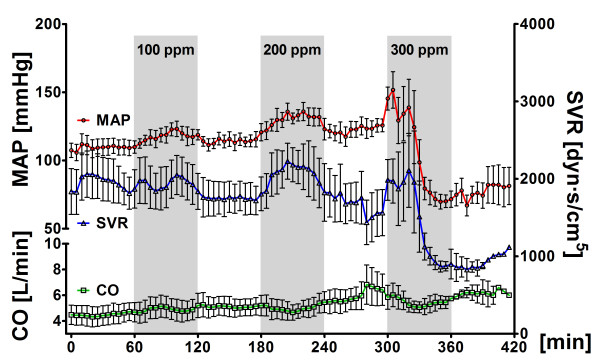

Figure 1.

Systemic vascular hemodynamics. Systemic vascular hemodynamics in five sheep challenged with alternate exposure to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) (gray bars) by ventilation of an extracorporeal membrane lung with 0 or 100 ppm H2S in air, 200 ppm H2S in air and 300 ppm H2S in air for 1-hour intervals each. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. MAP, mean arterial pressure; CO, cardiac output; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; ppm, parts per million.

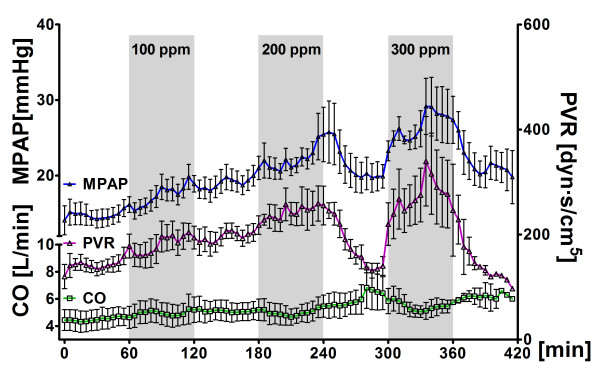

Figure 2.

Pulmonary vascular hemodynamics. Pulmonary vascular hemodynamics in five sheep challenged with alternate exposure to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) (gray bars) by ventilation of an extracorporeal membrane lung with 0 or 100 ppm H2S in air, 200 ppm H2S in air and 300 ppm H2S in air for 1-hour intervals each. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. MPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; CO, cardiac output; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; ppm, parts per million.

Results

Metabolic effects of H2S administration

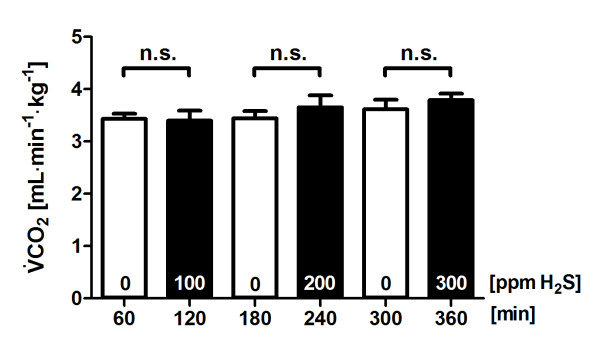

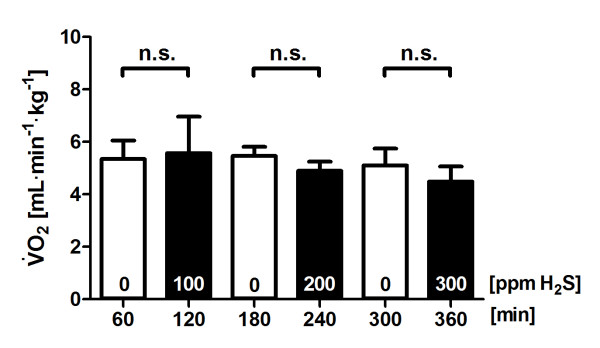

The baseline value was stably near approximately 3.4 ml∙kg-1∙min-1 when the ECML was ventilated with air. Direct diffusion of H2S into blood via the ECML at 100, 200 or 300 ppm did not alter (Figure 3) or (Figure 4). The temperature of the ECML heat exchanger water bath was kept at 38°C and resulted in a constant central blood temperature of 37.4 ± 0.4°C throughout the experiment (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Carbon dioxide production during administration of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Total carbon dioxide production () in five sheep challenged with alternate exposure to H2S by ventilation of an extracorporeal membrane lung with 0 or 100 ppm H2S in air, 200 ppm H2S in air and 300 ppm H2S in air for 1-hour intervals each. Values are derived from the last 10 minutes of each period of exposure to air or H2S and are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. ppm, parts per million; n.s. = P > 0.05.

Figure 4.

Oxygen consumption during administration of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Total carbon dioxide production () in five sheep challenged with alternate exposure to H2S by ventilation of an extracorporeal membrane lung with 0 or 100 ppm H2S in air, 200 ppm H2S in air and 300 ppm H2S in air for 1-hour intervals each. Values are derived from blood samples taken during the last 10 minutes of each period of exposure to air or H2S and are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. ppm, parts per million; n.s. = P > 0.05.

Table 1.

Hemodynamics and blood gas dataa

| Parameter | 0 ppm | 100 ppm | 0 ppm | 200 ppm | 0 ppm | 300 ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodynamics, means ± SD | ||||||

| HR, beats/min | 139 ± 24 | 148 ± 29 | 154 ± 5 | 172 ± 28 | 165 ± 28 | 150 ± 31 |

| MAP, mmHg | 110 ± 13 | 117 ± 14 | 115 ± 11 | 128 ± 16 | 121 ± 15 | 66 ± 11b |

| MPAP, mmHg | 15 ± 3 | 19 ± 3* | 19 ± 3 | 22 ± 4 | 20 ± 4.0 | 31 ± 7b |

| CO, l/min | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 1.7 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 5.5 ± 1.2 |

| CVP, mmHg | 9 ± 2 | 9 ± 1.0 | 10 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 8 | 8 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 |

| SVR, dyn·s/cm5 | 1,843 ± 435 | 1,948 ± 525 | 1,734 ± 412 | 2,009 ± 703b | 1,561 ± 553 | 870 ± 138b |

| PVR, dyn·s/cm5 | 145 ± 32 | 191 ± 52b | 203 ± 36 | 255 ± 70b | 138 ± 27 | 279 ± 138b |

| Hb, pH, blood gas tensions, and temperature, means ± SD | ||||||

| Hba, g/dl | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 9.0 ± 1.3 | 9.1 ± 1.0 | 11.1 ± 1.4b | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 9.6 ± 1.2 |

| pHa | 7.401 ± 0.072 | 7.369 ± 0.079 | 7.375 ± 0.051 | 7.346 ± 0.063 | 7.312 ± 0.089 | 7.217 ± 0.064b |

| PaO2, mmHg | 161 ± 28 | 150 ± 40 | 150 ± 37 | 107 ± 39 | 114 ± 36 | 83 ± 23b |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 38 ± 13 | 38 ± 11 | 35 ± 7 | 34 ± 5 | 36 ± 7.0 | 38 ± 4 |

| pHv | 7.383 ± 0.074 | 7.360 ± 0.080 | 7.360 ± 0.056 | 7.346 ± 0.066 | 7.302 ± 0.087 | 7.210 ± 0.068b |

| PvO2, mmHg | 50 ± 5 | 52 ± 6b | 52 ± 4 | 54 ± 4 | 56 ± 4 | 52 ± 7 |

| PvCO2, mmHg | 41 ± 14 | 41 ± 11 | 38 ± 8 | 35 ± 5 | 38 ± 6 | 40 ± 4 |

| Temperature,°C | 37.5 ± 0.6 | 37.5 ± 0.4 | 37.5 ± 0.3 | 37.3 ± 0.4 | 37.3 ± 0.4 | 37.1 ± 0.5 |

aHemodynamics and blood gas data in five sheep challenged with alternate exposure to H2S by ventilation of an extracorporeal membrane lung with 0 or 100 ppm H2S, 200 ppm H2S or 300 ppm H2S in air for 1-hour intervals each. ppm, parts per million; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; CO, cardiac output; CVP, central venous pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; Hba, arterial hemoglobin concentration; pHa, arterial pH; PaO2, arterial oxygen tension; PaCO2, arterial carbon dioxide tension; pHv, mixed venous pH; PvO2, mixed venous oxygen tension; PvCO2, mixed venous carbon dioxide tension. All values are means ± SD and reflect the last 10 minutes of each 1-hour period. n = 5. Values during H2S exposure were compared using Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with the preceding 0 ppm baseline period, that is, first vs. second hour, third vs. fourth hour and fifth vs. sixth hour; bP ≤ 0.05.

Hemodynamic effects of H2S administration

After 1 hour of exposure to either 100 or 200 ppm H2S via ECML ventilation and partial venoarterial perfusion, MAP was not different from baseline. However, exposure to 300 ppm H2S for 1 hour decreased MAP from 121 ± 15 mmHg to 66 ± 11 mmHg and reduced systemic vascular resistance (SVR) from 1561 ± 553 dyn·s/cm5 to 870 ± 138 dyn·s/cm5 (Table 1). We noted that MAP increased transiently during exposure to 100 and 200 ppm H2S (Figure 1) and that this increase was rapidly reversed upon application of air without added H2S. Subsequently, exposure to 300 ppm H2S induced a biphasic systemic pressor response characterized by increased MAP and SVR during the first 20 minutes of H2S exposure followed by a rapid decrease of MAP and pronounced irreversible hypotension (Figure 1).

MPAP and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) increased in response to H2S exposure, with the greatest increase (ΔMPAP, approximately 10 mmHg; ΔPVR, +51%) observed in response to 300 ppm H2S (Table 1). Time course analysis (Figure 2) suggested that PVR increased after exposure to 100, 200 and 300 ppm H2S in a reversible, dose-dependent manner. Heart rate and CO did not change in response to H2S exposure.

Pulmonary gas exchange and acid-base status

Arterial CO2 tension levels were within physiological limits throughout the experiment and did not change in response to H2S. Mixed venous CO2 tension (PvCO2) ranged between 35 and 41 mmHg and did not change in response to H2S. While arterial oxygenation (PaO2) was not significantly affected by 100 or 200 ppm H2S, PaO2 decreased from 114 ± 36 to 83 ± 23 mmHg (P ≤ 0.05) upon administration of 300 ppm H2S. Arterial oxygen tension did not recover during the subsequent interval of air exposure without H2S. Mixed venous O2 tension ranged between 50 and 56 mmHg, and there was no relevant change upon H2S administration. While arterial pH (pHa) was within physiological limits throughout the experiment, significant metabolic acidosis was observed during exposure to 300 ppm H2S, with concomitant changes in mixed venous pH. Arterial hemoglobin concentrations were near 9 g/dl throughout the experiment. Exposure to 200 ppm H2S transiently increased hemoglobin concentrations by 2 ± 0 g/dl (Table 1).

Total plasma sulfide concentrations

Plasma sulfide concentrations were determined in duplicate from arterial and ECML-efferent blood. The baseline plasma concentration of sulfide was 1.9 ± 0.3 μM, and this value was only slightly higher than the lower detection limit (approximately 1 μM) for this assay. Ventilation of ECML with air did not affect plasma sulfide concentrations in the efferent blood of the ECML. In ECML-efferent blood, plasma sulfide concentration increased to 7 ± 6, 27 ± 6 and 62 ± 12 μM/l during ECML ventilation with 100, 200 and 300 ppm H2S, respectively. However, no sulfide was detected in plasma samples of blood collected from the femoral artery during exposure to 100, 200 or 300 ppm H2S.

Discussion

The results of the present study reveal that ventilating an ECML with up to 300 ppm H2S in venoarterial cardiac bypass circulation does not reduce whole body CO2 production or O2 consumption in anesthetized sheep. In addition, we have demonstrated that administration of 300 ppm H2S via ECML ventilation causes significant adverse effects, including pulmonary vasoconstriction, systemic vasodilation and hypoxemia. The current results do not support the hypothesis that high concentrations of H2S delivered via an ECML can reduce the metabolic rate in large mammals at rest.

In an attempt to bypass the direct pulmonary toxicity of inhaled H2S, we used an ECML to directly diffuse high concentrations of H2S gas into the blood. The absence of H2S (lower limit of detection 1 ppm) in the gas outlet of the artificial lung during ventilation with up to 300 ppm H2S indicates that H2S is highly diffusible into blood through the membrane and that a single passage is sufficient for complete uptake of the gas. Thus, assuming complete uptake of H2S during ventilation of the ECML at a gas flow of 5 l/min with 300 ppm H2S (at standard conditions for temperature and pressure), a total amount of 1.5 ml of H2S (that is, approximately 67 μM) are administered via the membrane every minute. This sums to about 134 μM H2S/kg per hour delivered to a 30-kg sheep in the current study. In contrast, the total amount of H2S administered in previous studies in sheep [15] and pigs [16] were approximately 13 μM/kg/h and approximately 42 μM/kg/h, respectively, assuming complete uptake of H2S from the alveolar space and an alveolar ventilation of 6 l/min in a 74-kg sheep, and 1.2 l/min in a 6-kg pig. Therefore, the systemic dose of H2S supplied in the present study was about three times greater than that applied in pigs and 10 times greater than the dose applied in sheep. If any of the alveolar H2S were exhaled, the ratio of the uptake via the membrane artificial lung in the present study and the uptake via the natural lungs in previous reports would be even greater. Nonetheless, our measurements suggest that administration of H2S up to 134 μM/kg/h does not reduce or in sheep.

While H2S did not reduce or in sheep in the present study, Simon et al. [21] reported that continuous iv infusion of Na2S for 8 hours decreased the core body temperature and and levels in pigs, suggesting that it is possible to reduce metabolic rates in large mammals using a sulfide-based approach. However, it is important to note that hypothermia itself reduces the metabolic rate (Q10 effect). Therefore, in the current study, body temperature was kept at 37°C throughout the experiment to exclude any effects of hypothermia on metabolism. Whether systemic administration of Na2S reduces metabolic rates in large mammals when normothermia is maintained remains to be determined.

While our findings support the inability of H2S to reduce metabolism in large mammals, these results differ from observations in mice in which H2S inhalation markedly reduced metabolism [9,10,22]. Hydrogen sulfide may be one, but not the only, trigger for murine metabolic depression. Indeed, hypoxia, anemia and exposure to carbon monoxide have been reported to reduce aerobic metabolism in mice [23-25], but not in large mammals [26-28]. Of note is that mice are known to have a much higher specific metabolic rate (approximately 168 kcal kg-1∙d-1 in a 30-g mouse) than sheep (approximately 30 kcal kg-1∙d-1 in a 30-kg sheep) [29]. In a previous study, we reported that H2S inhalation reduced metabolism in awake, spontaneously breathing mice by about 40% during normothermia, resulting in a specific metabolic rate of no more than approximately 100 kcal∙kg-1∙d-1 [9]. In contrast, it has been reported that H2S inhalation at 100 ppm failed to reduce CO2 production in normothermic mice that were anesthetized and mechanically ventilated [30]. Interestingly, in anesthetized mice studied by Baumgart et al. [30], the baseline CO2 production rate before H2S inhalation was approximately 50% less than that in awake mice studied by Volpato et al. [9] in our laboratory. It is tempting to speculate that the ability of H2S to reduce metabolism depends on the specific metabolic rate of animals. H2S may reduce metabolism when the baseline rate of metabolism is high (for example, in awake mice), but not when the metabolic rate is already depressed (for example, in anesthetized mice or sheep).

Along these lines, it may be possible to reduce the metabolic rate in larger mammals using H2S when metabolism is increased. It has been reported that inhalation of 10 ppm H2S reduced oxygen consumption in exercising healthy volunteers, presumably due to inhibition of aerobiosis in exercising muscle [31]. Inhibitory effects of H2S in the presence of increased metabolism in larger mammals warrants further study.

Our results show that administration of H2S via a cardiopulmonary bypass circulation can cause significant dose-dependent pulmonary vasoconstriction. These observations are consistent with the pulmonary vasoconstrictor effects of H2S in mammalian pulmonary vessels reported by Olson et al. [32]. Although a potential role of H2S in hypoxia sensing (hence hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction) has been suggested [33], the mechanisms responsible for the pulmonary vasoconstrictor effects of H2S remain to be further elucidated.

Administration of H2S also tended to increase systemic vascular resistance, but resulted in systemic vasodilation after 30 minutes of ECML ventilation with 300 ppm H2S. This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that H2S can produce both vasoconstriction and vasorelaxation in isolated rat aortic ring segments in an O2 concentration-dependent manner. Koenitzer et al. [34] reported that H2S (5 to 80 μM Na2S solution) causes vasorelaxation at O2 concentrations reflecting the physiological oxygen tension in the peripheral vasculature (O2 concentration, 40 μM). In contrast, at high O2 concentrations (O2, 200 μM) under which H2S is rapidly oxidized to sulfite, sulfate or thiosulfate, the administration of 5 to 100 μM Na2S causes rat aortic vasoconstriction, and more than 200 μM Na2S are required to cause vasorelaxation [34]. Along these lines, the high oxygen tension observed in sheep on ECML when ventilated with 100 and 200 ppm of H2S may have contributed to the systemic vasoconstrictor effects of H2S in the present study, whereas vasodilation was only observed at the highest H2S concentration (300 ppm). In addition, the O2 dependency of H2S-mediated vasoconstriction may also explain why H2S caused vasoconstriction in the pulmonary vasculature, where O2 availability is consistently high.

While the toxicity of inhaling high levels of H2S is well documented, the reported toxicity of H2S concentrations up to 500 ppm is almost exclusively limited to mucosal membranes and the central nervous system [35-37]. However, the cardiovascular toxicity of high levels of inhaled H2S has not been reported. The observed pulmonary hypertension and apparent changes in systemic vascular tone in the current study may therefore represent previously unrecognized toxic effects of high levels of H2S in the circulation.

Despite the availability of various methods used to quantify sulfide in biological fluids, it remains challenging to measure circulating plasma concentrations of H2S [38]. The methylene blue formation method employed here measures "labile" total sulfide liberated from sulfur compounds, but not free H2S in blood and tissue. In the current study, considerable sulfide concentrations were detected in plasma obtained from blood efferent from the ECML, but not in the blood samples from the femoral artery (sampled less than approximately 10 seconds after the blood left the ECML). These observations suggest a rapid uptake of H2S into a variety of sulfide pools once H2S has entered the blood stream. Of note is that the measured plasma sulfide level of 62 μM/l in the ECML efferent blood diffused with 300 ppm H2S was only about 3% of the expected sulfide level of approximately 2,000 μM/l assuming a blood volume of 70 ml/kg. These results are consistent with a recent report that circulating free sulfide levels are almost undetectably low at baseline and that exogenous sulfide is also rapidly removed from the circulating plasma [39]. Nonetheless, the pronounced vasoreactivity induced by H2S administration observed in the current study suggests that H2S (and/or its active metabolites) is transported to the periphery and exerts biological effects. The fate of exogenously administered H2S remains to be determined in future studies using more sensitive methods.

Although the results of the current study do not suggest that H2S can be used to reduce metabolic rate in larger mammals, these results do not refute the potential organ protective effects of H2S reported elsewhere. The dose of 134 μM/kg/h that was applied here is almost 20 times higher than the effective dose of Na2S reported to improve survival in mice after cardiac arrest (0.55 μg/g, that is, approximately 7 μM/kg) [12]. Studies by others have also shown that administration of H2S donors in a similarly low dose range were able to protect organs from ischemic insults in rodents and pigs without reducing metabolic rate or body temperature [14,40]. Taken together, it is conceivable that organ-protective effects and metabolic effects of H2S may be mediated via two different mechanisms and/or at different concentrations.

Limitations

Measuring oxygen consumption is a valuable tool to assess metabolic rate. However, quantification of oxygen consumption in the setting of ECML requires serial simultaneous determinations of oxygen content in arterial and mixed venous blood as well as blood afferent and efferent to the ECML [41]. Small measuring inaccuracies in the parameters needed to calculate oxygen content (hemoglobin, oxygen saturation and tension) result in an exponential increase in the overall inaccuracy of the calculated value. In contrast, measuring CO2 production requires only CO2 quantification in the exhaled gas of both the natural and the artificial lung because virtually no CO2 is present in the inhaled gas mixture, which is a major advantage to simplifying the setup and avoiding exponential error. Therefore, may be the more reliable index for estimating the metabolic rate in this study.

The present study was designed to detect a reduction in metabolic rate of about 30% in sheep. On the basis of the variance of metabolic rates determined in pilot experiments in sheep, a sample size of 12 sheep was calculated to find a 30% reduction in metabolic rate (80% power and 5% probability of error). An interim analysis of this study (n = 5) did not substantiate a significant change or trend in (Figure 3) and precluded additional experiments.

Conclusions

The results of the present study demonstrate that ventilating an ECML with up to 300 ppm H2S in partial cardiopulmonary bypass circulation does not reduce CO2 production or O2 consumption in anesthetized sheep. Our results show that diffusion of up to 300 ppm H2S into blood via a membrane lung can cause dose-dependent pulmonary vasoconstriction, hypoxemia and catastrophic systemic vasodilation. These observations do not support the hypothesis that administration of a high concentration of H2S reduces metabolism in anesthetized large mammals. Whether the administration of H2S inhibits metabolism in large mammals when metabolic rate is increased (for example, systemic inflammation or exercise) remains to be determined.

Key messages

• High concentrations of H2S administered via ECML ventilation do not alter CO2 production in sheep on partial cardiopulmonary bypass perfusion.

• In this setting, H2S poses the risk of pulmonary vasoconstriction, hypoxemia and systemic vasodilation.

• Therefore, administration of high concentrations of H2S via membrane lung may not be useful for reducing oxidative metabolism in large mammals.

Abbreviations

caO2: arterial oxygen content; ceO2: efferent oxygen content; CO: cardiac output; CO2: carbon dioxide; cvO2: mixed venous oxygen content; CVP: central venous pressure; ECML: extracorporeal membrane lung; FeCl3: iron(III) chloride; FECO2: mean fraction of CO2 in expired air; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; Hb: hemoglobin concentration; HCl: hydrogen chloride; HR: heart rate; H2S: hydrogen sulfide; iv: intravenously; MAP: mean arterial pressure; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; MPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; NaHS: sodium hydrosulfide; Na2S: sodium sulfide; O2: oxygen; paCO2, PCWP: pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; arterial carbon dioxide tension; pHa: arterial pH; ppm: parts per million; pO2: oxygen tension; : carbon dioxide production; : oxygen consumption; : expiratory minute volume; : amount of CO2 exhaled from the lungs per unit of time; : amount of CO2 removed from the circulation via membrane oxygenator per unit of time.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MD and RCF performed the experiments and data analysis, contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and wrote the manuscript. KK performed plasma H2S measurements and helped perform the experiments. MB, EC and CA contributed to the study setup. WMZ and FI contributed to the conceptual design of the study, to the interpretation of data, and to manuscript writing and editing. WMZ and FI contributed equally to this study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Please see related commentary by Wagner et al., http://ccforum.com/content/15/2/146

Contributor Information

Matthias Derwall, Email: mderwall@partners.org.

Roland CE Francis, Email: rfrancis1@partners.org.

Kotaro Kida, Email: kkida@partners.org.

Masahiko Bougaki, Email: bogakim-tky@umin.ac.jp.

Ettore Crimi, Email: ettorecrimi@gmail.com.

Christophe Adrie, Email: cadrie@partners.org.

Warren M Zapol, Email: wzapol@partners.org.

Fumito Ichinose, Email: fichinose@partners.org.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by fellowship grants from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) to MD (DE 1685/1-1) and RCF (FR 2555/3-1), by laboratory funds of WMZ and National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL101930 to FI. CA was supported by the Arthur Sachs Scholarship Fund. We are indebted to Dr. Kenneth D. Bloch from the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, for advice and assistance in the design of the study and in the editing of the manuscript.

References

- Arrich J, Holzer M, Herkner H, Mullner M. Hypothermia for neuroprotection in adults after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. p. CD004128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fukudome EY, Alam HB. Hypothermia in multisystem trauma. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S265–272. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181aa60ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigore AM, Murray CF, Ramakrishna H, Djaiani G. A core review of temperature regimens and neuroprotection during cardiopulmonary bypass: does rewarming rate matter? Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1741–1751. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c04fea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polderman KH. Mechanisms of action, physiological effects, and complications of hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S186–202. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181aa5241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries M, Stoppe C, Brücken D, Rossaint R, Kuhlen R. Influence of mild therapeutic hypothermia on the inflammatory response after successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest. J Crit Care. 2009;24:453–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman DC, Moulin FJ, McManus BE, Mahle KC, James RA, Struve MF. Cytochrome oxidase inhibition induced by acute hydrogen sulfide inhalation: correlation with tissue sulfide concentrations in the rat brain, liver, lung, and nasal epithelium. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:18–25. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struve MF, Brisbois JN, James RA, Marshall MW, Dorman DC. Neurotoxicological effects associated with short-term exposure of Sprague-Dawley rats to hydrogen sulfide. Neurotoxicology. 2001;22:375–385. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(01)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpato GP, Searles R, Yu B, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Bloch KD, Ichinose F, Zapol WM. Inhaled hydrogen sulfide: a rapidly reversible inhibitor of cardiac and metabolic function in the mouse. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:659–668. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318167af0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone E, Roth MB. Suspended animation-like state protects mice from lethal hypoxia. Shock. 2007;27:370–372. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31802e27a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison ML, Blackwood JE, Lockett SL, Iwata A, Winn RK, Roth MB. Surviving blood loss using hydrogen sulfide. J Trauma. 2008;65:183–188. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181507579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamishima S, Bougaki M, Sips PY, Yu JD, Minamishima YA, Elrod JW, Lefer DJ, Bloch KD, Ichinose F. Hydrogen sulfide improves survival after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation via a nitric oxide synthase 3-dependent mechanism in mice. Circulation. 2009;120:888–896. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.833491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, Jiao X, Scalia R, Kiss L, Szabo C, Kimura H, Chow CW, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodha NR, Clements RT, Feng J, Liu Y, Bianchi C, Horvath EM, Szabo C, Sellke FW. The effects of therapeutic sulfide on myocardial apoptosis in response to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouzi P, Notet V, Chenuel B, Chalon B, Sponne I, Ogier V, Bihain B. H2S induced hypometabolism in mice is missing in sedated sheep. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;160:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang G, Cai S, Redington AN. Effect of inhaled hydrogen sulfide on metabolic responses in anesthetized, paralyzed, and mechanically ventilated piglets. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:110–112. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298639.08519.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp RO Jr, Bus JS, Popp JA, Boreiko CJ, Andjelkovich DA. A critical review of the literature on hydrogen sulfide toxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1984;13:25–97. doi: 10.3109/10408448409029321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiffenstein RJ, Hulbert WC, Roth SH. Toxicology of hydrogen sulfide. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;32:109–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel LM. A Direct Microdetermination for Sulfide. Anal Biochem. 1965;11:126–132. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(65)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:589–601. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(98)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon F, Giudici R, Duy CN, Schelzig H, Oter S, Groger M, Wachter U, Vogt J, Speit G, Szabo C, Radermacher P, Calzia E. Hemodynamic and metabolic effects of hydrogen sulfide during porcine ischemia/reperfusion injury. Shock. 2008;30:359–364. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181674185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone E, Morrison M, Roth MB. H2S induces a suspended animation-like state in mice. Science. 2005;308:518. doi: 10.1126/science.1108581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier H, Bonora M. Ventilatory and metabolic responses to cold and CO-induced hypoxia in awake rats. Respir Physiol. 1994;97:79–91. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M, Igisu H, Tanaka I, Hori H, Koga M. Effects of hypo- and hyperglycemia on brain energy metabolites in mice exposed to carbon monoxide. Toxicol Lett. 1994;73:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer D. Metabolic adaptation to hypoxia: cost and benefit of being small. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;141:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster HV, Bisgard GE, Klein JP. Effect of peripheral chemoreceptor denervation on acclimatization of goats during hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50:392–398. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frappell P, Lanthier C, Baudinette RV, Mortola JP. Metabolism and ventilation in acute hypoxia: a comparative analysis in small mammalian species. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:R1040–1046. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.6.R1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korducki MJ, Forster HV, Lowry TF, Forster MM. Effect of hypoxia on metabolic rate in awake ponies. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:2380–2385. doi: 10.1063/1.357585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Nielsen K. Scaling: Why is Animal Size so Important? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgart K, Wagner F, Groger M, Weber S, Barth E, Vogt JA, Wachter U, Huber-Lang M, Knoferl MW, Albuszies G, Georgieff M, Asfar P, Szabó C, Calzia E, Radermacher P, Simkova V. Cardiac and metabolic effects of hypothermia and inhaled hydrogen sulfide in anesthetized and ventilated mice. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:588–595. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b9ed2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhambhani Y, Burnham R, Snydmiller G, MacLean I. Effects of 10-ppm hydrogen sulfide inhalation in exercising men and women. Cardiovascular, metabolic, and biochemical responses. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39:122–129. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Dombkowski RA, Russell MJ, Doellman MM, Head SK, Whitfield NL, Madden JA. Hydrogen sulfide as an oxygen sensor/transducer in vertebrate hypoxic vasoconstriction and hypoxic vasodilation. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:4011–4023. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Whitfield NL, Bearden SE, St Leger J, Nilson E, Gao Y, Madden JA. Hypoxic pulmonary vasodilation: a paradigm shift with a hydrogen sulfide mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R51–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00576.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenitzer JR, Isbell TS, Patel HD, Benavides GA, Dickinson DA, Patel RP, Darley-Usmar VM, Lancaster JR Jr, Doeller JE, Kraus DW. Hydrogen sulfide mediates vasoactivity in an O2-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1953–1960. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01193.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSHA/EPA Occupational Chemical Database. http://www.osha.gov/web/dep/chemicaldata/

- WHO International Programme on Chemical Safety. http://www.who.int/ipcs/en/

- Guidotti TL. Hydrogen Sulfide: Advances in Understanding Human Toxicity. Int J Toxicol. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kajimura M, Fukuda R, Bateman RM, Yamamoto T, Suematsu M. Interactions of multiple gas-transducing systems: hallmarks and uncertainties of CO, NO, and H2S gas biology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:157–192. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield NL, Kreimier EL, Verdial FC, Skovgaard N, Olson KR. Reappraisal of H2S/sulfide concentration in vertebrate blood and its potential significance in ischemic preconditioning and vascular signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1930–1937. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson PW, Weinstein AL, Sung J, Singh SP, Nagineni V, Spector JA. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury in in vitro and in vivo models of intestine free tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:1670–1678. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d4fdc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider M, Zapol W. In: Artificial Lungs and Acute Respiratory Failure: Theory and Practice. Zapol W, Qvist J, editor. Washington, D.C.: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1976. Assessment of pulmonary oxygenation during venoarterial bypass with aortic root return; pp. 257–273. [Google Scholar]