Abstract

This case describes and reports the effects of a multi-component collaborative intervention to treat difficult behaviors in a 79-year-old woman with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). To assess for cognitive status and disruptive behavior patterns, we collected a cognitive screen, history of presenting illness, and measures of behavior problems prior to the intervention. The intervention included 32 weekly 1-hour sessions with the patient, 1-hour sessions with the patient’s assigned caregiver and regular interactions with the patient’s family and medical treatment team. All sessions were conducted at the patient’s long-term residential care facility. We assessed behavior disturbances with the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI). We assessed functional abilities with the Katz Activities of Daily Living (K-ADL), and assessed cognitive function with the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE). At the closing session (week 32) caregiver ratings indicated significantly reduced scores on the CMAI (Baseline = 75 to Endpoint = 30) and maintenance in ADLs (Baseline=3 to Endpoint=3). Caregivers reported enhanced efficacy in treating behaviors and improvement in their relationship with the patient. Results demonstrate the benefits of a multi-component collaborative intervention, based on an enhanced environment and behavioral approach, in treating behavior problems related to DLB.

Introduction and Background

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is considered the second most prevalent dementia after Alzheimer’s disease (AD), comprising 15–25% of all dementias 1–3. Core features include dementia, fluctuating consciousness, hallucinations, paranoid delusions, parkinsonism, and neuroleptic sensitivities 2, 3. Hallucinations and delusions have been the most diagnostically specific neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) distinguishing DLB from AD 4, 5. A recent study indicated significant levels of aggressive behaviors on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) in DLB patients 5, with rates similar to that of AD patients.

NPS associated with DLB are very upsetting to family and facility caregivers 6, 7. NPS leads to poor quality of life for patients and caregivers and contributes to psychiatric morbidity in caregivers if they do not feel effective in managing these symptoms 8. Therefore, finding effective techniques for managing NPS in DLB patients is a critical goal for clinicians and families.

Managing DLB related symptoms is complicated 9. Neuroleptics are most commonly used to managing agitated behaviors in dementia. However, these medications tend to be less effective in general 10–12, and in DLB patients are particularly concerning because of their sensitivities to these medications 3, 13, 14. Behavioral strategies are a viable alternative to medication management 15–18. Successful models combine a behavioral approach, medical consultation, and family involvement. A number of reports suggest that of all the interventions available, behavioral models maybe the best available treatments for agitation in general dementia patients19. Interestingly, there are no studies or reports that study these behavioral approaches to address disruptive behaviors in DLB. Symptoms in DLB differ from AD and, therefore, treatment approaches may require further modifications to accommodate these differences. The purpose of this case study is to provide a descriptive report for professionals caring for DLB and to highlight the need for more evidence based interventions for treating DLB related problem behaviors.

Intervention: The Collaborative and Multi-component Approach

The SBHS was a demonstration project funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The goal of the SBHS project was to develop and disseminate evidence-based treatments of depression and agitation into long-term care facilities. The SBHS collaborated with 14 facilities (6 board and care, 5 small to mid size long term care facilities and 3 skilled nursing facilities). The SBHS project was developed based on the chronic disease management model 20.

This model includes several components:

provider training in the recognition and management of dementia and accompanying neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), which included five training modules and a follow-up training session provided in a group format;

consumer and family education about NPS;

improved coordination of care through: (a) assessment, (b) treatment tracking and monitoring of patient outcomes to the intervention, and (c) involving professional caregiving staff and family in the development and application of the intervention; and (d) better access to specialty services and collaboration between specialty care and primary care.

A care manager is a critical component of this model. The care manager provides training to staff, coordinates and provides assessments and treatments, facilitates family-staff-provider communication, and monitors patient progress. The care managers in the project included two licensed clinical social workers, one marriage and family therapist, and three clinical psychologists. DG’s care manager was a licensed social worker with over 4 years of interventions experience with children and adults.

Assessment of the Case Patient

The care manager conducted a baseline assessment, using the Folstein Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) to determine cognitive status21; the Katz-Activities of Daily Living (K-ADL) to assess DG’s ability to perform every day tasks, such as dressing, toileting, and feeding 22; and the Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) to assess frequency and intensity of DG’s agitated behaviors 23. In addition to these functional measures the care manager also assessed for potential triggers and consequences to DG’s disruptive behavior, using the Motivation Assessment Scale (MAS) 24. She also completed the Reinforcer Assessment for Individuals with Severe Disabilities (RAIS-D) to identify pleasurable activities and objects, which she used in the intervention 25. Finally, she completed the Pleasant Event Schedule (PES) to identify objects/activities for reinforcement of appropriate behaviors in the individualized intervention plan 26. These measures were completed every two weeks for 32 weeks. All measures were used as clinical as well as empirical tools to assess and monitor behavior changes and may be suitable for use in many different clinical settings.

The care manager became the central liaison for all providers involved in the patient’s care, including primary care, psychiatrists, adult day health programs, and family members. However, the following sections will provide reports of her interactions primarily with DG, RM, and facility staff.

Results of Assessment

DG demonstrated severe impairment on the MMSE (0 out of 30). DG was able to identify common objects in her room (i.e., chair) and items in a coloring book (i.e., cat). The care manager also assessed typical day-to-day memory, and on most sessions DG indicated memory for the name of her primary professional caregiver and the care manager. However, DG was often not oriented to date, time, and place.

The CMAI identified the following target behaviors: hoarding, hitting, making strange noises and/or pushing away caregivers and previously described yelling, cursing, banging the walls and doors, and hallucinations. The MAS found that triggers to hitting, kicking and pushing away included: 1) attempts to help DG with ADL’s; 2) urinary tract infections; and 3) excess noise and activity on the floor. Caregivers reported decreasing their activities with DG because they believed her symptom of masked faces, i.e., flat affect, “furrowed” facial expression, indicated displeasure or anger. As a result, DG was left largely alone and understimulated (please see the Table for presentation of target behaviors and antecedents).

Table 1.

Assessment and Plan

| Target Behaviors | Goals | Antecedent | Plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive behaviors: Hitting, Kicking, and Pushing away | Reduce aggressive behaviors |

|

|

| “unpredictable outbursts”: yelling, cursing, banging on walls and doors | Reduce unpredictable outbursts, increase CG’s self-efficacy |

|

|

| Isolative | Increase stimulation and interactions with staff and other resident’s |

|

|

Intervention Plan

The care manager developed a clinical plan based on the cognitive, behavioral and environmental assessment (Table). An essential aspect of DG’s care plan involved psychoeducation about DLB to RM and residential staff. For example, it was important to teach the staff that DG’s cognitive status may fluctuate daily because of her DLB. In addition, staff were taught that DLB affected DG’s ability to interpret and respond to social situations appropriately, such as her persistent frown. Caregivers were instructed about using DG’s behavioral cues to determine optimal times to engage DG in dressing, brushing teeth, and bathing. For example, when DG raised her hand, this indicated DG was not ready for them to approach. Instead, the caregivers were taught to return later, and inform her that they were there to help her with an activity.

Caregivers learned to adjust their expectation that DG “actively” engage in activities and to broaden their understanding about the different ways in which people communicate and participate. For example, DG, communicated through her behaviors that instead of actively coloring she preferred to simply watch those around her color and draw, which could be considered a form of participation. When DG seemed to refuse an activity by shaking her head, pushing caregivers away, or deeper furrowing of her eyebrows, DG was communicating her desire to just observe. Finally, staff members were taught how to assess and manage DG’s symptoms, and monitor for any medical problems that could exacerbate her symptoms (i.e. UTI’s, dehydration, sleep deprivation, pain, etc.).

To increase DG’s activities, caregivers were educated that her flat/angry affect did not always indicate displeasure, but was related to her parkinsonism from DLB and to continue to engage her in activities despite her flat affect. Caregivers began to use this new knowledge about DLB to adapt their caregiving techniques/approaches to meet DG’s needs. They learned to become more sensitive, observant, patient, and flexible around providing care.

The MAS assessment indicated that DG’s target behaviors of yelling or hitting the door were motivated by DG’s need to escape from noisy or populated situations. Caregivers, were taught to ensure DG had a quiet and calm space, and were able to make continual adjustments in the environment to meet this need. They would either take her for a walk or take her to her room and turn on her favorite music.

The PES and the RAIS-D suggested that DG enjoyed the following pleasurable activities: gentle balloon tossing, rolling a ball on the floor for her to kick with her feet, drawing in a coloring book and watching others draw, naming pictures of animals, flowers, and other objects, folding clothes/laundry, writing down familiar names on a piece of paper, listening to soft music, and watching people dance. Caregivers began to introduce these activities as a way to distract or redirect DG when she was resisting care or getting upset. For instance, while bathing DG, they would often sing and dance around her when she became upset.

The care manager assisted with the implementation of care plans by providing updates and feedback to RM regarding the progress of the intervention and the consultation she provided the staff. RM was provided additional reference and background material about DLB to gain greater understanding of her mother’s symptoms. RM was also educated about how DG’s symptoms might impact her interactions with her caregivers.

Outcome

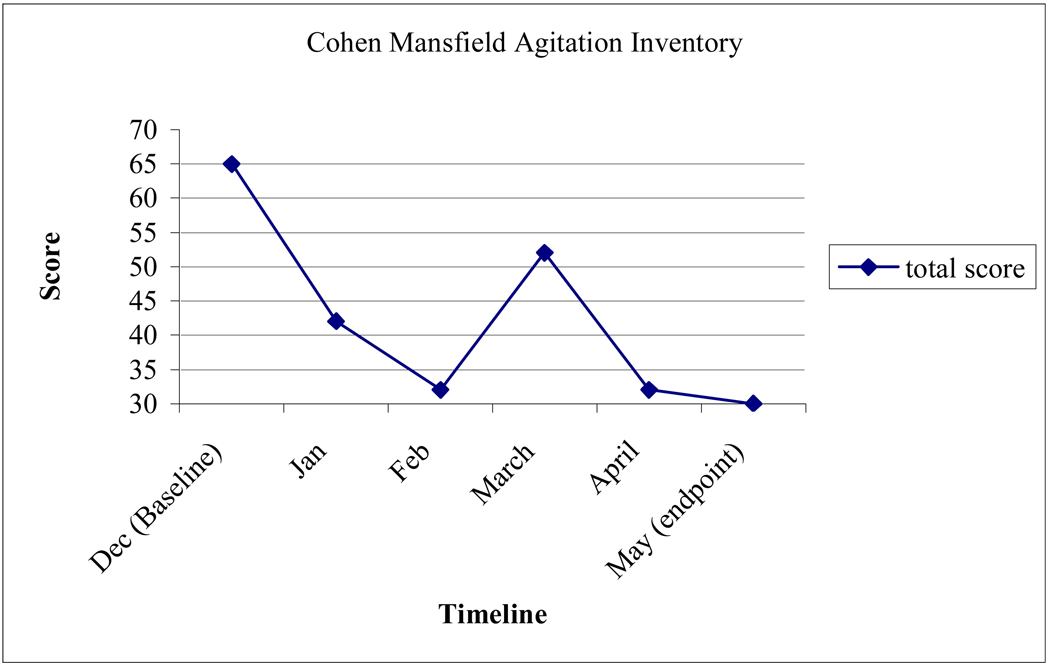

Scores on the CMAI decreased considerably, indicating a significant reduction in her agitated behavior due to the 32-week intervention (Figure 1). DG experienced several fluctuations on measures due to medical issues such as a UTI. On target behaviors, there were significant declines in verbal aggression (baseline=4, endpoint=1), hitting (baseline=4, endpoint=1), pushing (baseline=3, endpoint=1), hoarding (baseline=6, endpoint=1), and repetitious mannerisms (baseline= 6, endpoint=1) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) Total Scores.*

*Notes: 1) A total score of 30 would indicate that the client never showed any of the presented disruptive behaviors in the past week. A high of 120 points is possible. 2) Although outcome measures were acquired every two weeks, the figures demonstrate behaviors at the beginning of each month to facilitate data presentation.

Figure 2.

Change scores on target behaviors at baseline on the CMAI.

Scores: 1=Never, 2=Less than once a week, 3= One or two times a week, 4=Several times a week, 5=Once or twice a day, 6=Several times a day, 7=Several times an hour.

Informally, caregivers reported gaining significant knowledge of dementia, increased self-efficacy in managing DG’s behaviors, and increased pleasure in interacting with DG. Although DG continued to refuse care at times and to experience active hallucinations that caused her to yell, the staff felt more comfortable redirecting her. RM reported significant alleviation of her anxiety about her mother’s hallucinations and behaviors. RM also began to work in a more collaborative manner with the caregivers and felt that she was able to make more informed decisions about DG’s healthcare.

Discussion and Conclusion

DLB leads to significant distress in formal and informal caregivers and is among the most difficult disorders to manage. This case study demonstrates the effectiveness of a collaborative and environmentally driven approach for addressing agitation in DLB. This approach has been effective for use in assisted living facilities for Alzheimer’s disease patients 16, and this case report indicates the same may be true for patients with DLB. This case report shows that a combination of education, assessing the triggers for agitation and the consequences of that behavior can lead to an effective plan to help reduce and manage these troubling behaviors.

Finally, care managers and existing facility staff were quite diverse in their clinical training and indicate that the model used in this project may be suitable for a range of clinical practitioners. DG had demonstrated several aggressive behaviors that caregivers in both her facilities described as “care-resistant” and “intimidating.” These behaviors contributed to DG’s reduced quality of life due to the difficulty caregivers experienced in interacting with DG. Following implementation of the intervention, DG’s agitated behaviors decreased considerably and staff reported that management was far easier. This case study demonstrates the utility of a tailored empirically supported behavioral and environmental approach to addressing difficult behaviors in DLB.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported solely by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration grant H79-SM52236. There were no other financial or other relationships that could be interpreted as a conflict of interest affecting this manuscript.

References

- 1.Goldstein MA, Price BH. Non-Alzheimer dementias. In: Samuels MA, Feske SK, editors. Office Practice of Neurology. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. pp. 873–886. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKeith I, Mintzer J, Aarsland D, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol. 2004 Jan;3(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005 Dec;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballard C, Holmes C, McKeith I, et al. Psychiatric Morbidity in Dementia With Lewy Bodies: A Prospective Clinical and Neuropathological Comparative Study With Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 July;156(7):1039–1045. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelborghs S, Maertens K, Nagels G, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: cross-sectional analysis from a prospective, longitudinal Belgian study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 Nov;20(11):1028–1037. doi: 10.1002/gps.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodaty H, Green A, Koschera A. Meta-Analysis of Psychosocial Interventions for Caregivers of People with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):657–664. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan LL, Wong HB, Allen H. The impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia on distress in family and professional caregivers in Singapore. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005 Jun;17(2):253–263. doi: 10.1017/s1041610205001523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mausbach BT, Patterson TL, von Kanel R, et al. Personal mastery attenuates the effect of caregiving stress on psychiatric morbidity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006 Feb;194(2):132–134. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198198.21928.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boeve BF. Clinical, diagnostic, genetic and management issues in dementia with Lewy bodies. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005 Oct;109(4):343–354. doi: 10.1042/CS20050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia: A Review of the Evidence. JAMA. 2005 February;293(5):596–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002 Apr;287(16):2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang CH, Tsai SJ, Hwang JP. The efficacy and safety of quetiapine for treatment of geriatric psychosis. J Psychopharmacol. 2005 November;19(6):661–666. doi: 10.1177/0269881105056669. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell S, Stephens S, Ballard C. Dementia with Lewy bodies: clinical features and treatment. Drugs Aging. 2001;18(6):397–407. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanctot KL, Herrmann N. Donepezil for behavioural disorders associated with Lewy bodies: a case series. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000 Apr;15(4):338–345. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(200004)15:4<338::aid-gps119>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of Collaborative Care for Older Adults With Alzheimer Disease in Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2006 May;295(18):2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolanowski AM, Litaker M, Buettner L. Efficacy of theory-based activities for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Nurs Res. 2005 Jul-Aug;54(4):219–228. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001 Fall;9(4):361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moniz-Cook E, Stokes G, Agar S. Difficult behaviour and dementia in nursing homes: Five cases of psychosocial intervention. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2003;10:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxman TE, et al. Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2002 Nov;53(11):1419–1431. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. Bmj. 2000 Feb 26;320(7234):569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. the Index of Adl: a Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963 Sep;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol. 1989 May;44(3):M77–M84. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.m77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durrand YM, Crimius DB. The Motivation Assessment Scale (MAS) Administration Guide. Syracus, NY: Program Development Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher JE, Harsin CM, Hadden JE. Professional Psychology in Long Term Care. New York: Harleigh Co.; 2000. Behavioral interventions for patients with dementia in long term facilities. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teri L, Lewinsohn P. Modification of the Pleasant and Unpleasant Events Schedules for use with the elderly. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982 Jun;50(3):444–445. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]