Abstract

Background

The iso-osmolar contrast agent iodixanol may be associated with a lower incidence of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) than low-osmolar contrast media (LOCM), but previous meta-analyses have yielded mixed results. Objectives: To compare the incidence of CI-AKI between iodixanol and LOCM.

Methods

Studies were identified from literature searches to December 2009, clinicaltrials.gov, and conference abstracts from the past 2 years including 2010. Only prospective, randomized comparisons between iodixanol and LOCM with CI-AKI [increase in serum creatinine (sCr) ≥0.5 mg/dl or ≥25% from baseline, as defined in the trial] as a primary and/or secondary endpoint and a Jadad score ≥2 were included. A random-effects model was used to obtain pooled relative risks (RRs) for CI-AKI in analyses based on route of administration [intra-arterial (IA) or intravenous (IV)], definition of CI-AKI, and timing of sCr measurements.

Results

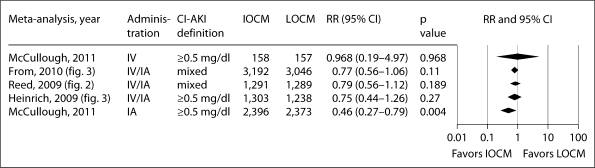

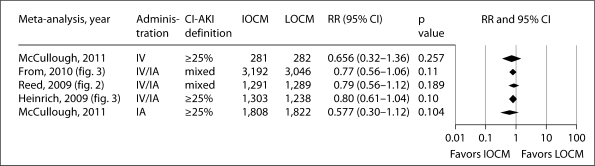

145 potential articles were identified, of which 25 were included in the meta-analysis. Following IA administration (n = 19), the RR for CI-AKI (≥0.5 mg/dl definition) with iodixanol, compared with LOCM, was 0.462 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.272–0.786, p = 0.004, 15 studies]. Using the ≥25% definition, there was a lower incidence of CI-AKI with iodixanol versus LOCM, but the difference was not statistically significant (RR: 0.577, 95% CI: 0.297–1.12, p = 0.104, 11 studies). In the IV trials, there was no significant difference in the incidence of CI-AKI using either definition (≥0.5 mg/dl definition: RR: 0.967, 95% CI: 0.188–4.972, p = 0.968, 3 trials; ≥25% definition: RR: 0.656, 95% CI: 0.316–1.360, p = 0.257, 4 trials).

Conclusions

IA but not IV administration of iodixanol is associated with a significantly lower risk of CI-AKI than LOCM.

Key Words: Acute kidney injury, Clinical trials, Contrast agents, Iodixanol, Iso-osmolar contrast agent, Low-osmolar contrast agent, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI), formerly referred to as contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), is defined as an impairment in renal function [an increase in serum creatinine (sCr) ≥0.5 mg/dl or ≥25% from baseline] that occurs within 3 days after the administration of contrast medium (CM), for which no alternative cause can be found [1]. Using the ≥0.5 mg/dl definition, CI-AKI occurs in approximately 3.3% of cases as reported in the Mayo Clinic Registry of percutaneous coronary interventions in unselected patients receiving CM [2]. It is the third most common cause of hospital-acquired renal failure, accounting for 11% of cases of hospital-acquired renal insufficiency [3]. CI-AKI is an important clinical concern because it can prolong hospitalization and is associated with an increased risk of permanent kidney damage or death [4,5,6]. The risk of CI-AKI is increased in patients with risk factors such as preexisting diabetic nephropathy [7].

A meta-analysis of individual patient data from 16 randomized, controlled trials found that the iso-osmolar CM (IOCM) iodixanol (Visipaque™; GE Healthcare, Princeton, N.J., USA) was associated with smaller increases in mean sCr and a lower incidence of CI-AKI compared with low-osmolar CM (LOCM), particularly in those with both chronic kidney disease (CKD) and diabetes mellitus (DM) [8]. Three other systematic reviews and tabular meta-analyses, however, found no significant differences in the risk of CI-AKI between iodixanol and LOCM as a class, although the CI-AKI rates were lower with iodixanol [9,10,11].

The outcomes of such analyses are dependent on the studies selected for inclusion. Studies comparing iodixanol and LOCM have varied widely in the patient populations included, the definition of CI-AKI, the LOCM used, the route of administration, and the timing and frequency of sCr determinations after the procedure. The timing of sCr measurements is particularly important [12] because a number of studies have shown that peak sCr concentrations occur at different times after the procedure, depending on the CM used; hence the reported incidence of CI-AKI may depend on when sCr is measured [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The frequency of sCr measurements at fixed time points is important to capture a true peak that is needed to calculate a more accurate incidence of CI-AKI. In view of these differences, the present meta-analysis was performed to compare the incidence of CI-AKI in comparative studies of iodixanol and LOCM, taking both the definition of CI-AKI and the timing of sCr determinations into account.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

This meta-analysis included randomized, prospective, head-to-head comparisons of iodixanol and LOCMs with CI-AKI as a primary and/or secondary endpoint. CI-AKI could be defined as an increase in sCr of either ≥0.5 mg/dl or ≥25% from baseline, and CM could be given by either the intra-arterial (IA) or intravenous (IV) route. sCr determination was performed either at standardized time points (one or more sCr measurements at fixed times; i.e., 24, 36, and/or 72 h after CM administration), or at non-standardized ones (single sCr measurement done when feasible within a range; i.e., at any time between 48 and 120 h).

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Literature searches to December 2009 were performed in BioBase, Biological Abstracts, CAB Abstracts, Embase, International Pharmaceuticals Abstracts, Life Sciences Collection, MEDLINE, MEDLINE Preprints, Energy Database, and Technology Collection. The search strategy was: (Visipaque∗; iodixanol; 92339-11-2\AL\SU\TM\RN) and (randomized controlled∗; comparative study∗; clinical trial\TD\DT) and (CIN; contrast-induced neph∗; contrast induced<2>nephropathy∗; creatinine\AL) and (iopamidol; Isovue∗; Niopam∗; Iopamiro∗; iohexol; Omnipaque∗; Accupaque∗; iomeprol; Iomeron∗; iopromide; Ultravist∗; ioversol; Optiray∗; ioxilan; Oxilan∗; ioxaglate; Hexabrix∗\AL\SU\TM). In addition, we searched clinicaltrials.gov and abstracts from relevant medical conferences for the past 2 years, including 2010, to identify any recent trials that may be missed in the literature search.

For each trial, the incidence of CI-AKI, defined as an increase in sCr of either ≥0.5 mg/dl or ≥25% from baseline, in each treatment group was extracted. These study level data were entered into a standardized Excel template, and were assessed for quality and consistency. Study quality was assessed by means of the 5-point Jadad score [20], and only studies with a score ≥2 were included in the analysis. All data, including Jadad scoring, were entered by an independent consultant biostatistician (Adrienne H. Groulx) listed in the Acknowledgment section. These data were reviewed by another biostatistician (Sujatha Sundaram) as well as by the first author (P.A.M.). All data passed internal review, with no issues identified with the Jadad scoring.

Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were descriptive in nature. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables included the count and proportion, mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and median. Categorical variables were summarized counts with proportions or means with standard deviations, as appropriate. All statistical tests were two sided, and p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Baseline demographic characteristics were compared using Student's t tests, χ2 tests, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests of the weighted averages, as appropriate, for the combined study population.

For each trial, the relative risk (RR) of CI-AKI and the standardized mean difference in sCr between iodixanol and pooled LOCM were determined. Subset analyses were performed to compare iodixanol and each LOCM; however, to avoid publication bias, subset analysis was performed only if ≥3 comparator studies were available.

Studies were pooled based on IA or IV administration and meta-analyses were performed using the random-effects model of DerSimonian and Laird [21] to obtain pooled RRs, pooled differences in sCr increase (weighted mean differences), and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for outcomes. Statistical heterogeneity of trial results was tested using the Cochran Q statistic and I2; for the Q statistic, and a difference with p < 0.10 was considered significant.

Separate analyses were performed on trials that measured sCr at standardized time points and those that did not, using the bias-corrected standardized mean difference (Hedges’ g) [22]. Within these two groups, differences in CI-AKI were analyzed for iodixanol versus all LOCMs and iodixanol versus each LOCM (when ≥3 comparator studies were available).

Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the effect of baseline sCr level, age, percentage of female subjects, percentage of diabetic individuals, and severity of renal dysfunction. These analyses were performed using meta-regression analysis for continuous variables and one-way analysis of variance for categorical variables. In each analysis, the RR of CI-AKI was the dependent variable and the study characteristic was the independent variable.

Study level data were examined for potential publication bias using the tests of Egger et al. [23] and Begg and Mazumdar [24], and by funnel plots of log-transformed RRs against the corresponding standard errors.

Results

Studies and Patients Included

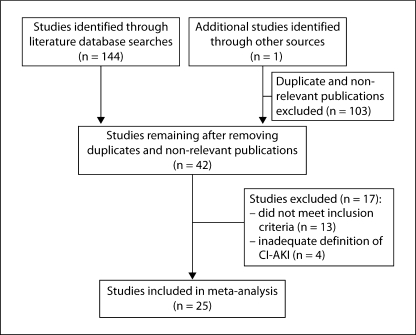

The initial literature search identified 144 potential references, which were reviewed for relevance; an additional study [25], identified through the abstract search, was added before the analysis. A total of 103 duplicate or non-relevant publications were excluded, leaving 42 studies that were reviewed for inclusion in the analysis. Of these, 17 studies were subsequently excluded: 13 did not meet one or more inclusion criteria, and in 4 the definition of CI-AKI was inadequate (fig. 1). Thus, a total of 25 studies were included in the final analysis (table 1) [14,15,16,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Of these, CM was given IA in 19 and IV in 6. CI-AKI was defined as a ≥0.5 mg/dl increase in sCr in 15 IA studies and 3 IV studies, and as a ≥25% increase in sCr in 11 IA and 4 IV studies. A total of 17 studies (14 IA and 3 IV) were available for comparisons of standardized and non-standardized sCr measurements. The Jadad scores of the included studies ranged from 2 to 5.

Fig. 1.

Study selection.

Table 1.

Studies included in the meta-analysis (n = 25)

| Ref. | First author (year) | Sample size | Jadad score | LOCM | Endpoints reported |

sCr measurement |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI-AKI definition ↑ |

ΔsCr vs. baseline | fixed time points | non-standardized | ||||||

| ≥0.5 mg/dl | ≥25% | ||||||||

| IA administration | |||||||||

| 26 | Aspelin (2003) | 129 | 4 | iohexol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 27 | Hill (1994) | 200 | 4 | iohexol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 28 | Sinha (2004) | 70 | 2 | iohexol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 29 | Chalmers (1999) | 102 | 2 | iohexol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 30 | Jakobsen (1996) | 16 | 2 | iohexol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 31 | Kløw (1993) | 72 | 2 | iohexol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 32 | Wessely (2009) | 324 | 4 | iomeprol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 15 | Hardiek (2008) | 102 | 5 | iopamidol | ✓ | ||||

| 33 | Laskey (2009) | 418 | 3 | iopamidol | ✓ | ||||

| 16 | Solomon (2007) | 414 | 5 | iopamidol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 34 | Feldkamp (2006) | 221 | 3 | opromide | ✓ | ||||

| 35 | Juergens (2009) | 191 | 4 | opromide | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 36 | Li (2008) | 87 | 2 | opromide | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 37 | Nie (2008) | 208 | 5 | opromide | ✓ | ||||

| 25 | Han (2010) | 1,656 | 3 | opromide | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 38 | Hernández (2009) | 250 | 2 | oversol | ✓ | ||||

| 14 | Rudnick (2008) | 299 | 5 | oversol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 39 | Jo (2006) | 275 | 5 | oxaglate | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 40 | Mehran (2009) | 146 | 4 | oxaglate | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| IV administration | |||||||||

| 41 | Kolehmainen (2003) | 50 | 2 | obitridol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 42 | Chuang (2009) | 50 | 3 | iohexol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 43 | Thomsen (2008) | 148 | 4 | iomeprol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 44 | Fischbach (1996) | 117 | 5 | iopamidol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 45 | Kuhn (2008) | 248 | 4 | iopamidol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 46 | Nguyen (2008) | 117 | 5 | opromide | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

Demographic characteristics of the patients included in these studies are summarized in table 2. Of note, there were considerable differences among the studies in the risk for CI-AKI according to baseline renal function. Considering analyses of CI-AKI using either definition, for studies in which CM was given IV, the included population was of lower risk with younger patients, a narrower range of baseline sCr levels, and a lower proportion of diabetic patients compared to studies in which CM was administered IA. However, none of the pooled demographic data was statistically significant between the IOCM (iodixanol) and LOCM groups.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic characteristics of the patients given IOCM (iodixanol) or LOCM

| First author | LOCM | Patients, n | Females, n (%) | Mean age, years | Mean weight, kg | Mean baseline sCr mg/dl | Mean GFR ml/min/1.73 m2 | Diabetic patients % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOCM | LOCM | IOCM | LOCM | IOCM | LOCM | IOCM | LOCM | IOCM | LOCM | IOCM | LOCM | IOCM | LOCM | ||

| IA administration | |||||||||||||||

| Aspelin [26] | iohexol | 64 | 65 | 23 (35.9) | 30 (46.2) | 71.1±6.0 | 70.6±8.6 | 76.51±2.4 | 77.21±4.4 | 1.49±0.52 | 1.60±0.52 | 44.8 | 40.1 | 100 | 100 |

| Hill [27] | iohexol | 101 | 99 | 20 (19.8) | 12(12.1) | 61±10 | 59±11 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sinha [28] | iohexol | 35 | 35 | NR | NR | 69.4±8.3 | 72.4±5.8 | NR | NR | >1.6 | >1.6 | 45.7 | 45.3 | 40.0 | 34.3 |

| Chalmers [29] | iohexol | 54 | 48 | 15 (27.8) | 15(31.3) | 62 | 64.6 | NR | NR | 3.05 | 3.34 | 20.6 | 18.2 | 31.0 | 35.0 |

| Jakobsen [30] | iohexol | 8 | 8 | 1(12.5) | 3 (37.5) | 55 | 58 | 81 | 74 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 6.9 | 0 | 0 |

| KløW [31] | iohexol | 35 | 37 | NR | NR | 549 | 55±9 | 80±10 | 81±13 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Wessely [32] | iomeprol | 162 | 162 | 43 (26.5) | 46 (28.4) | 75±9.1 | 73.2±9.1 | NR | NR | 1.36±0.51 | 1.37±0.33 | 46.4±9.3 | 47.1±9.0 | 37.0 | 37.7 |

| Hardiek [15] | iopamidol | 54 | 48 | 28 (51.9) | 16(33.3) | 65±10 | 66±10 | NR | NR | 0.91±0.22 | 0.93±0.24 | 77.0 | 79.0 | 100 | 100 |

| Laskey [33] | iopamidol | 215 | 203 | 76 (35.3) | 72 (35.5) | 69.6±8.7 | 69.7±9.2 | NR | NR | 1.60 | 1.51 | 41.5 | 44.4 | 100 | 100 |

| Solomon [16] | iopamidol | 210 | 204 | 83 (39.5) | 66 (32.4) | 70.5±9.9 | 72.4±9.0 | 86.7±20.6 | 82.7±17.7 | 1.44±0.41 | 1.46±0.36 | 50.2±13.0 | 49.3±11.6 | 43.8 | 38.2 |

| Feldkamp [34] | opromide | 105 | 116 | 26 (24.8) | 28(24.1) | 60.6±10 | 62.1±9.2 | NR | NR | 1.04±0.18 | 1.03±0.19 | 72.3 | 72.9 | 40.0 | 35.0 |

| Juergens [35] | opromide | 91 | 100 | 29 (20.9) | 27 (27.0) | 70.2±9.2 | 69.4±10.2 | 80.3±14.6 | 82.6±15.0 | 1.6±10.43 | 1.63±0.42 | 47.6±16.5 | 45.6±15.0 | 35.0 | 46.0 |

| Li [36] | opromide | 44 | 43 | 21 (47.7) | 20 (46.5) | 67.4±6.2 | 68.2±5.8 | NR | NR | 1.60±0.52 | 1.49±0.53 | 41.4 | 43.8 | 100 | 100 |

| Nie [37] | opromide | 106 | 102 | 33(31.1) | 33 (32.4) | 61±11.5 | 60±12.3 | NR | NR | 1.48±0.59 | 1.49±0.49 | 47.2 | 46.9 | 27.4 | 26.5 |

| Han [25] | opromide | 828 | 828 | 280 (33.8) 292 (35.3) | 69±10 | 68±13 | NR | NR | 1.8±10.32 | 1.76±0.67 | 36.2 | 37.4 | 29 | 28.5 | |

| Hernandez [38] | oversol | 118 | 132 | 45 (38.1) | 47 (35.6) | 69±9 | 70±8 | NR | NR | 1.04±0.43 | 1.06±0.46 | 72.7±26.4 | 76.1±25.1 | 100 | 100 |

| Rudnick [14] | oversol | 156 | 143 | 50 (32.1) | 37 (25.9) | 71.1±9.9 | 72.6±10.2 | 89.2±21.4 | 90.2±19.5 | 1.99±0.60 | 1.92±0.60 | 36.5±11.3 | 38.8±11.1 | 52.0 | 51.8 |

| Jo [39] | oxaglate | 140 | 135 | 61 (43.6) | 60 (44.4) | 66.1±8.6 | 68.7±7.5 | 59.7±9.4 | 59.8±9.5 | 1.38±0.56 | 1.30±0.50 | 48.6 | 51.5 | 34.4 | 36.3 |

| Mehran [40] | oxaglate | 72 | 74 | 9(12.5) | 9 (12.2) | 71.6±9.9 | 71.3±12.3 | NR | NR | 1.86±0.34 | 1.80±0.29 | 37.0 | 38.5 | 51.4 | 40.5 |

| IV administration | |||||||||||||||

| Kolehmainen [41] | obitridol | 25 | 25 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2.60±1.59 | 2.74±2.18 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Chuang [42] | iohexol | 25 | 25 | 7 (28.0) | 9 (36.0) | 62.9±13.7 | 53±12.2 | 66.1±9.7 | 68±11.8 | 1.36±0.42 | 1.34±0.45 | 52.2 | 53.8 | 40.0 | 36.0 |

| Thomsen [43] | iomeprol | 72 | 76 | 26 (36.1) | 18 (23.7) | 65.4±12.1 | 67.1±14.1 | 67.9±13.2 | 66.7±12.6 | 1.70±0.70 | 1.70±0.60 | 39.1 | 40.3 | 12.5 | 27.6 |

| Fischbach [44] | iopamidol | 60 | 57 | 14 (23.3) | 13(22.8) | 61.9±10.7 | 60.2±10.5 | 74.4±14.9 | 76.5±14.0 | 1.00±0.15 | 1.10±0.35 | 75.7 | 68.3 | NR | NR |

| Kuhn [45] | iopamidol | 123 | 125 | 61 (49.6) | 71 (56.8) | 68.3±9.2 | 69.5±10.1 | 84.2±21.0 | 83.6±19.3 | 1.4±10.38 | 1.46±0.44 | 49.9±11.6 | 47.6±13.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Nguyen [46] | opromide | 61 | 56 | 16 (26.2) | 18(32.1) | 63.0±11.7 | 65.8±13.4 | 88.7±20.0 | 83.9±24.6 | 1.77±0.24 | 1.75±0.32 | 51.5±16.6 | 53.0±26.0 | 37.7 | 17.9 |

Means ± SD or numbers of patients (%) are shown. GFR = Glomerular filtration rate; NR = not reported.

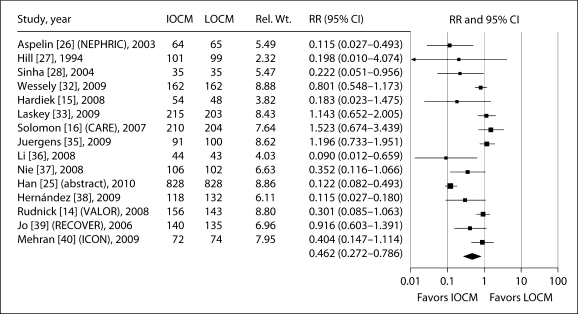

Incidence of CI-AKI after IA Administration

In 15 of the 19 trials using IA administration, CI-AKI was defined as ≥0.5 mg/dl increase in sCr from baseline. In these studies, the RR for CI-AKI with iodixanol compared with LOCM was 0.462 (95% CI: 0.272–0.786, p = 0.004). RRs in individual trials ranged from 0.090 to 1.523 (fig. 2). There was significant (p < 0.001) heterogeneity between studies, but no evidence of publication bias (table 3). Three studies compared iodixanol and iohexol. Meta-analysis of these studies showed a significant reduction in the risk of CI-AKI with iodixanol compared with iohexol (RR: 0.163, 95% CI: 0.062–0.433, p = 0.0003). Three studies compared iodixanol and iopamidol, one of which used non-standardized measurements of sCr. Meta-analysis of these studies showed no significant difference in the risk of CI-AKI with iodixanol compared with iopamidol (RR: 1.067, 95% CI: 0.533–2.135, p = 0.855). Due to the small number of studies for ioversol, ioxaglate and iomeprol, CI-AKI analyses were not performed.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of the incidence of CI-AKI (defined as ≥0.5 mg/dl increase in sCr from baseline) in trials reporting this outcome comparing IA iodixanol (IOCM) with LOCM.

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the incidence of CI-AKI in trials comparing iodixanol and LOCM

| Studies n | Iodixanol n/totaln | LOCM n/total n | RR | 95% CI | P value | I2 | Heterogeneity p value | Publication bias p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies (standardized and non-standardized sCr determinations) | |||||||||

| IA studies | |||||||||

| ≥0.5 mg/dl | 15 | 188/2,396 | 440/2,373 | 0.462 | 0.272-0.786 | 0.004 | 86.37 | <0.001 | 0.511 |

| ≥25% | 11 | 183/1,808 | 554/1,822 | 0.577 | 0.297-1.120 | 0.104 | 91.45 | <0.001 | 0.210 |

| IV studies | |||||||||

| ≥0.5 mg/dl | 3 | 12/158 | 14/157 | 0.967 | 0.188-4.972 | 0.968 | 67.71 | 0.045 | 0.355 |

| ≥25% | 4 | 17/281 | 28/282 | 0.656 | 0.316-1.360 | 0.257 | 26.29 | 0.254 | 0.518 |

| Standardized sCr determinations only | |||||||||

| IA studies | |||||||||

| ≥0.5 mg/dl | 14 | 174/2,186 | 431/2,169 | 0.419 | 0.241-0.728 | 0.002 | 86.55 | <0.001 | ND |

| ≥25% | 10 | 157/1,598 | 534/1,618 | 0.526 | 0.262-1.053 | 0.07 | 90.91 | <0.001 | ND |

| IV studies | |||||||||

| ≥0.5 mg/dl | 1 | 3/61 | 10/56 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| ≥25% | 2 | 6/86 | 17/81 | 0.346 | 0.144-0.830 | 0.017 | ND | 0.418 | ND |

ND = Not determined. Publication bias was determined using the test of Egger et al. [23].

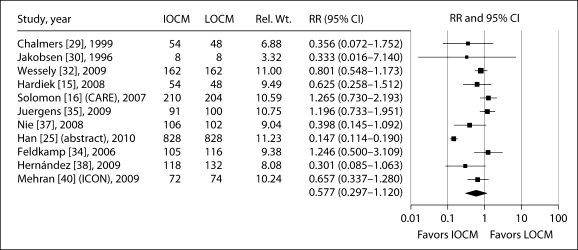

In the 11 IA studies in which CI-AKI was defined as an increase in sCr of ≥25% from baseline, there was a trend towards a decreased risk of CI-AKI with iodixanol compared with LOCM (table 3; fig. 3), but this did not reach statistical significance (RR: 0.577, 95% CI: 0.297–1.12, p = 0.104). There was significant heterogeneity between trials (p < 0.001) but no evidence of publication bias (table 3).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of the incidence of CI-AKI (defined as ≥25% increase in sCr from baseline) in trials reporting this outcome comparing IA iodixanol (IOCM) with LOCM.

Similar results were seen when the meta-analyses were limited to trials in which sCr was measured at standardized time points. In the 14 IA studies where CI-AKI was defined as an increase in sCr from baseline of ≥0.5 mg/dl, iodixanol was associated with a significantly decreased risk compared with LOCM (RR: 0.419, 95% CI: 0.241–0.728, p = 0.002). In the 10 IA studies with standardized sCr measurements where CI-AKI was defined as an increase in sCr of ≥25%, there was a trend towards a decreased risk with iodixanol, but this did not reach statistical significance (RR: 0.526, 95% CI: 0.262–1.053, p = 0.07). In both cases, there was significant (p < 0.001) heterogeneity between studies.

Incidence of CI-AKI after IV Administration

In the 3 studies where CM were given IV, there was no significant difference in the incidence of CI-AKI when defined as an increase in sCr from baseline of ≥0.5 mg/dl between iodixanol and LOCM (RR: 0.967, 95% CI: 0.188–4.972, p = 0.968). Two of these 3 studies used non-standardized measurement of sCr after contrast exposure. There was significant (p = 0.045) heterogeneity between these 3 studies but no evidence of publication bias (table 3). Similarly, in the 4 studies where CI-AKI was defined as an increase in sCr from baseline of ≥25%, iodixanol was not associated with a significant reduction in risk compared with LOCM (RR: 0.656, 95% CI: 0.316–3.160, p = 0.257). Two of these 4 studies used non-standardized measurement of sCr. There was no significant heterogeneity between these 4 studies (p = 0.254).

Only 1 study using the ≥0.5 mg/dl definition of CI-AKI used standardized sCr determinations, and hence no analysis could be performed. In this trial, a significantly lower percentage of patients receiving iodixanol developed CI-AKI compared with iopromide (5.1 vs. 18.5%, p = 0.037) [46]. Standardized sCr determinations were performed in 2 studies in which the ≥25% definition was used. The combined data from these studies showed a significant reduction in the risk of CI-AKI with iodixanol compared with LOCM (RR: 0.346, 95% CI: 0.144–0.830, p = 0.017). There was no significant heterogeneity between these studies (p = 0.416), but an analysis of publication bias could not be performed with only 2 studies.

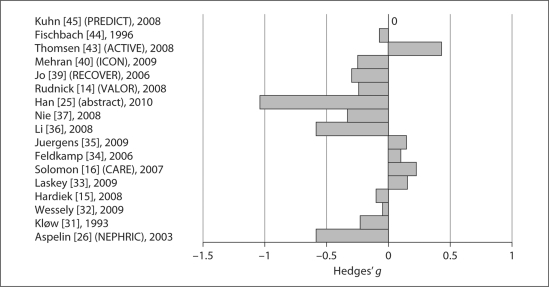

Mean Increases in sCr

Mean changes in sCr, expressed as Hedges’ [22] parameter g, in the 17 studies (14 IA/3 IV) available for comparison of sCr measurements are shown in figure 4. In the 13 IA trials with standardized sCr determinations, there were no significant differences in changes in sCr between iodixanol and pooled LOCMs, or between iodixanol and iopromide. No analyses were performed comparing iodixanol with each of the other LOCMs because the inclusion of only 1 or 2 studies could result in reporting bias. There was only 1 IA study which used non-standardized sCr measurements, so no analyses could be performed [16]. Two of the 3 IV studies identified for this analysis used non-standardized sCr measurements and no analysis was performed [43,45].

Fig. 4.

Mean changes in sCr in studies with standardized sCr determinations. The effect size was expressed as Hedges’ g[22].

Meta-Regression Analyses

Considering the IA studies only, meta-regression analysis for the incidence of CI-AKI, measured as an increase in sCr from baseline of ≥0.5 mg/dl, showed increasing age (p < 0.001), male gender (p < 0.001), and DM (p = 0.007) to be significant independent variables; when the incidence of CI-AKI was measured as an increase in sCr from baseline of ≥25%, increasing age, female gender, DM, and baseline sCr (all p < 0.001) were significant independent variables. Meta-regression analyses of the IV studies were either not performed because of the small number of studies or did not show these variables to be significantly related to the incidence of CI-AKI.

Discussion

We found that IA administration of iodixanol was associated with a lower risk of CI-AKI compared with LOCM using the more conservative rise in sCr of ≥0.5 mg/dl definition and a numerically lower risk, although not significant, using the ≥25% definition. The baseline sCr across all included studies was ≥1.6 mg/dl and average glomerular filtration rate was ≤50 ml/min/1.73 m2, indicating that the patients had, on average, moderately impaired renal function. For IV administration, there was no difference in CI-AKI between iodixanol and LOCM. However, when the analysis was limited to studies in which sCr was measured at standardized fixed times after IV administration (an a priori hypothesis), iodixanol was associated with a reduction in CI-AKI in 2 trials which used the ≥25% increase in sCr definition (p = 0.017). However, there was only 1 IV trial that used the ≥0.5 mg/dl definition, and in this trial, RR for CI-AKI for iodixanol was 0.276, 95% CI 0.082–0.928, and p = 0.037 [46]. This difference between the IA and IV results may reflect the observation that the patients recruited into trials using IV administration of CM often had exclusion criteria for an elevated sCr and were at lower risk of CI-AKI (younger, lower proportion of diabetics, and narrower range of baseline sCr) compared with the patients included in trials with IA administration of CM.

The present analysis extends the observations by McCullough et al. [8] in an earlier analysis (2006) of individual patient data from 16 randomized trials comparing IA iodixanol and LOCM, which found that the incidence of CI-AKI was significantly lower in patients receiving iodixanol (1.4 vs. 3.5%), and that the maximum increase in sCr was smaller. Subsequent meta-analyses of CI-AKI in patients receiving iodixanol or LOCM have yielded conflicting results. Heinrich et al. [9] found no significant difference in the CI-AKI risk between iodixanol and LOCM in an analysis of 25 trials using either IA or IV administration of CM pooled together (RRpooled: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.61–1.04, p = 0.1 using the 25% definition, and RRpooled: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.44–1.26, p = 0.27 using the 0.5 mg/dl definition); however, the risk was significantly lower with iodixanol than with iohexol in patients with renal insufficiency who received IA CM (RRpooled: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.21–0.68, p < 0.01). In another meta-analysis, which included data from 2,763 patients in 16 randomized trials, Reed et al. [10] found that iodixanol was not associated with a lower risk of CI-AKI compared with LOCM, but was associated with a significantly lower rate of CI-AKI compared with iohexol (RRpooled: 0.19, 95% CI: 0.07–0.56, p = 0.002) and with ioxaglate (RRpooled: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.37–0.92, p = 0.022). Finally, a recent meta-analysis by From et al. [11], which included 36 trials (n = 7,166 patients) with no restriction on the definition of CI-AKI, journal type, or patient population, reported no significant difference in CI-AKI incidence between iodixanol and LOCM (RRpooled: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.56–1.09, p = 0.11). Subgroup analyses, however, showed a significant difference between iodixanol and LOCM in studies defining CI-AKI as an increase in sCr from baseline ≥25% (RRpooled: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.40–0.85, p = 0.006), between iodixanol and iohexol (RRpooled: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.11–0.55, p < 0.001), and a nearly significant difference between iodixanol and ionic dimers (RRpooled: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.39–1.01, p = 0.05). Figures 5 and 6 show the results of the present meta-analysis together with the previous ones, according to populations administered CM via the IA, mixed IA-IV, and IV route alone. Thus, these figures demonstrate for both CI-AKI definitions that as one narrows the populations down to those undergoing IA procedures, iodixanol is associated with a lower risk of CI-AKI compared to LOCM.

Fig. 5.

Compilation of pooled odds ratios for IA, IV, and mixed IA and IV meta-analyses of the incidence of CI-AKI (defined as ≥0.5 mg/dl increase in sCr vs. baseline) demonstrating a leftward shift in pooled estimates moving from IV, to mixed IV/IA, and IA trials. Pooled odds ratios from meta-analyses by Heinrich et al. [9], Reed et al. [10] and From et al. [11].

Fig. 6.

Compilation of pooled odds ratios for IA, IV, and mixed IA and IV meta-analyses of the incidence of CI-AKI (defined as ≥25% increase in sCr vs. baseline) demonstrating a leftward shift in pooled estimates moving from IV, to mixed IV/IA, and IA trials. Pooled odds ratios from meta-analyses by Heinrich et al. [9], Reed et al. [10] and From et al. [11].

The lack of concordance of studies selected for the meta-analyses discussed above explains, in part, the differing results. Two of the studies included in this analysis [26,31] were also included in all 4 previous meta-analyses. The present meta-analysis has 4 trials [26,27,30,31] in common with the previous meta-analysis by McCullough et al. [8]; 12 others were not included either because CI-AKI was not a primary/secondary endpoint or data were not available. The present meta-analysis has 13 trials [15,16,26,27,28,29,30,31,34,41,43,44,45] in common with Heinrich et al. [9]. Twelve others were identified by our search but not included because CI-AKI was not a primary/secondary endpoint, the Jadad score was 1 or the study details were unclear; 12 trials not included in Heinrich et al. [9] were included here. The present meta-analysis has 12 trials [14,16,26,29,31,34,35,39,40,43,45,46] in common with Reed et al. [10]. Four others were not included because CI-AKI was not a primary/secondary endpoint, the Jadad score was 1 or the study details were unclear; 13 trials not included in Reed et al. [10] were included here. The present meta-analysis has 20 trials [14,15,16,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,39,40,42,43,44,45,46] in common with From et al. [11]; 16 trials included in their study did not meet the inclusion criteria here and 5 others not included in From et al. [11] were included here.

We selected only prospective, randomized, head-to-head comparative studies, with CI-AKI as a primary and/or secondary endpoint, and a Jadad score ≥2. These stringent criteria excluded the IMPACT study [47], which evaluated 166 patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment and reported that the risk of CI-AKI was similar following IV administration of iodixanol or iopamidol. The inclusion of this study in previous meta-analyses has been criticized because IMPACT was a post hoc combination of 2 small trials in which image quality was the primary endpoint [12]; thus, it cannot be considered a prospective randomized trial of CI-AKI prevention.

Our meta-analysis was influenced by a recent, large, prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing iodixanol and iopromide [25], which was reported as an abstract from the EuroPCR meeting of interventional cardiovascular specialists in Paris, May 2010. This new trial, which included 1,656 evaluable patients, showed that iodixanol was associated with a significantly lower incidence of CI-AKI, defined as either an absolute increase in sCr of ≥0.5 mg/dl (3.2 vs. 26.3%, p < 0.001) or a relative increase of ≥25% (7.1 vs. 48.4%, p < 0.001). Similar risk reductions were seen for iodixanol versus iopromide in various patient subgroup analyses: with or without DM, baseline CrCl 30–45 or 46–59 ml/min, age 60–75 years or >75 years, CM volume <140 or >140 ml, and patients receiving coronary angiography with or without percutaneous coronary intervention.

Because iodixanol tends to have an earlier rise in sCr than LOCM in CI-AKI [48], we took into consideration when sCr was measured after CM exposure. For example, in the CARE trial when blood samples were taken between 45 and 71 h after the procedure, iodixanol was associated with a numerically greater incidence of CI-AKI compared with iopamidol (7.4 vs. 2.9% using the ≥0.5 mg/dl definition; 12.6 vs. 6.5% using the ≥25% definition); however, when blood samples were taken between 71 and 96 h after the procedure, the converse was true, that is, iodixanol was associated with a numerically lower incidence of CI-AKI compared with iopamidol (3.4 vs. 14.8% using the ≥0.5 mg/dl definition; 13.8 vs. 29.6% using the ≥25% definition) [16]. Thus, it is critical for trials to measure multiple sCr values after CM exposure at standardized intervals (24, 48, 72, and 96 h) in order to identify the peak value for each contrast agent. CI-AKI (defined as ≥0.5 mg/dl and ≥25% increase in sCr from baseline) developed in a total of 8.3% of patients over the 2-day period. However, CI-AKI was seen in 1.5% of patients at 24 h but not at 48 h, in 1.9% of patients at both 24 and 48 h, and in 4.9% of patients at 48 h but not at 24 h [49].

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (2007) recommended the use of IOCM in CKD patients undergoing angiography. The most recent update in 2009, however, states that in patients with CKD undergoing angiography who are not on chronic dialysis, either an IOCM (level of evidence: A) or a LOCM other than ioxaglate or iohexol is indicated (level of evidence: B) [50]. We anticipate our results may stimulate specific recommendations for IA and IV forms of angiography in the future.

There is strong biologic plausibility for iodixanol in reducing the risk of CI-AKI compared with LOCM because of its iso-osmolality, that is, osmolality comparable to that of blood. Hyperosmolarity of CM may play a role in the pathogenesis of CI-AKI by causing relatively greater degrees of intrarenal vasoconstriction, activating tubuloglomerular feedback, or increasing tubular hydrostatic pressure, all of which could result in decreased glomerular filtration and worsening medullary hypoxemia [51]. With respect to the differences in rates and risk of IV versus IA administration, most of the IV studies had exclusion criteria for elevated sCr, and thus included lower risk subjects. In addition, IV injection of CM may allow for more admixing with the blood pool, and thus a more diluted flow of CM entering the renal vasculature. Finally, IA utilization in most cases involves manipulation of catheters in the central aorta and presents the possibility of superimposed cholesterol microembolism as an additional renal insult to CM.

Our study has all the limitations of meta-analyses that summarize trial results up to a point in time. Importantly, the number of IV studies is sufficiently small to limit inferences made with respect to this route of administration. We attempted to reduce variability by including only prospective, randomized, head-to-head comparisons of iodixanol and LOCM that were of high quality as assessed by Jadad score and we observed no evidence of publication bias. A considerable limitation of the studies is the use of biochemical definitions of CI-AKI, i.e., a short-term change in sCr from baseline, rather than clinical outcomes such as the need for additional therapy (e.g., hemodialysis), progression of CKD, rehospitalization, or mortality, which are known to be related to CI-AKI [2,52,53]. Finally, we recognize that heterogeneity of trial designs, inclusion/exclusion criteria, clinical settings, number and timing of creatinine measurements, definitions of CI-AKI, and other elements represents a residual threat to validity that cannot be quantitatively expressed using meta-analytic tools.

In conclusion, in patients with CKD at increased risk, IA but not IV administration of iodixanol is associated with a significantly lower risk of CI-AKI than LOCM.

Disclosure Statement

This meta-analysis was funded by one of the worldwide manufacturers of iodixanol (Visipaque), GE Healthcare, Inc., Medical Diagnostics, Princeton, N.J., USA. GE Healthcare directly contracted with Nerac, Inc., Toland, Conn., USA, for access and maintenance of the library of papers and abstracts used in the study. GE Healthcare also directly contracted with i3 Statprobe, Inc., Ann Arbor, Mich., USA, and PAREXEL International, Hackensack, N.J., USA, for the above-listed services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Adrienne H. Groulx (M.Sc., Senior Biostatistician, i3 Statprobe employee) for assisting, under supervision by the authors, with data extraction and statistical analyses. They also acknowledge the assistance of Sujatha Sundaram (PhD., i3 Statprobe consultant), also under supervision by the authors, in table formatting. Editorial support was provided, under the direction of the authors, by Sharon Schaier, PhD, at PAREXEL International for paper assembly and text formatting.

References

- 1.Morcos SK. Contrast medium-induced nephrotoxicity. In: Dawson P, Cosgrove DO, Grainger RG, editors. Textbook of Contrast Media. Oxford: Isis Medical Media; 1999. pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, Berger PB, Ting HH, Best PJ, Singh M, Bell MR, Barsness GW, Mathew V, Garratt KN, Holmes DR., Jr Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002;105:2259–2264. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016043.87291.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nash K, Hafeez A, Hou S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:930–936. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, Davidson C, Lameire N, Stacul F, Tumlin J, CIN Consensus Working Panel Risk prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:27K–36K. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dangas G, Iakovou I, Nikolsky E, Aymong ED, Mintz GS, Kipshidze NN, Lansky AJ, Moussa I, Stone GW, Moses JW, Leon MB, Mehran R. Contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary interventions in relation to chronic kidney disease and hemodynamic variables. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisbord SD, Chen H, Stone RA, et al. Associations of increases in serum creatinine with mortality and length of hospital stay after coronary angiography. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2871–2877. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toprak O. Conflicting and new risk factors for contrast induced nephropathy. J Urol. 2007;178:2277–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullough PA, Bertrand ME, Brinker JA, Stacul F. A meta-analysis of the renal safety of isomolar iodixanol compared with low-osmolar contrast media. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinrich MC, Häberle L, Müller V, Bautz W, Uder M. Nephrotoxicity of iso-osmolar iodixanol compared with nonionic low-osmolar contrast media: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology. 2009;250:68–86. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2501080833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed M, Meier P, Tamhane UU, Welch KB, Moscucci M, Gurm HS. The relative renal safety of iodixanol compared with low-osmolar contrast media: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:645–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.From AM, Al Badarin FJ, McDonald FS, Bartholmai BJ, Cha SS, Rihal CS. Iodixanol versus low-osmolar contrast media for prevention of contrast induced nephropathy: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:351–358. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.917070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantor E, Lim L. The relative renal safety of iodixanol compared with low-osmolar contrast media (letter) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1163–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudnick MR, Goldfarb S, Wexler L, Ludbrook PA, Murphy MJ, Halpern EF, Hill JA, Winniford M, Cohen MB, VanFossen DB. Nephrotoxicity of ionic and nonionic contrast media in 1196 patients: a randomized trial. The Iohexol Cooperative Study. Kidney Int. 1995;47:254–261. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudnick MR, Davidson C, Laskey W, Stafford JL, Sherwin PF, VALOR Trial Investigators Nephrotoxicity of iodixanol versus ioversol in patients with chronic kidney disease: the Visipaque Angiography/Interventions with Laboratory Outcomes in Renal Insufficiency (VALOR) Trial. Am Heart J. 2008;156:776–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardiek KJ, Katholi RE, Robbs RS, Katholi CE. Renal effects of contrast media in diabetic patients undergoing diagnostic or interventional coronary angiography. J Diabetes Complications. 2008;22:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon RJ, Natarajan MK, Doucet S, Sharma SK, Staniloae CS, Katholi RE, Gelormini JL, Labinaz M, Moreyra AE. Cardiac Angiography in Renally Impaired Patients (CARE) study: a randomized double-blind trial of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2007;115:3189–3196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddan D, Laville M, Garovic VD. Contrast-induced nephropathy and its prevention: what do we really know from evidence-based findings? J Nephrol. 2009;22:333–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguiar-Souto P, Valero-Gonzalez S. When to test renal function to disclose contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:371. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Downes MO, Nicholson A. Re: contrast-induced nephropathy: are there differences between low osmolar and iso-osmolar iodinated contrast media? Clin Radiol. 2010;65:343–345. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Ed Stat. 1981;6:107–128. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han Y, Wang S, Wang X, Li F, Zhao X, Jing Q. Contrast-induced nephropathy following coronary intervention in elderly, renally impaired patients: a ramdomised comparison of the renal safety of iodixanol and iopromide (abstract) EuroIntervention. 2010;6(suppl H):H62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aspelin P, Aubry P, Fransson SG, Strasser R, Willenbrock R, Berg KJ. Nephrotoxic effects in high-risk patients undergoing angiography. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:491–499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill JA, Cohen MB, Kou WH, Mancini GB, Mansour M, Fountaine H, Brinker JA. Iodixanol, a new isosmotic nonionic contrast agent compared with iohexol in cardiac angiography. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha SK, Berry WAD, Bueti J, et al. The Prevention of Radiocontrast-induced Nephropathy Trial (PRINT): a prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of iso-osmolar versus low-osmolar radiocontrast in combination with N-acetylcysteine versus placebo (abstract) Circulation. 2004;110(suppl 5):377. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalmers N, Jackson RW. Comparison of iodixanol and iohexol in renal impairment. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:701–703. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.859.10624328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakobsen JA, Berg KJ, Kjaersgaard P, Kolmannskog F, Nordal KP, Nossen JO, Rootwelt K. Angiography with nonionic X-ray contrast media in severe chronic renal failure: renal function and contrast retention. Nephron. 1996;73:549–556. doi: 10.1159/000189139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kløw NE, Levorstad K, Berg KJ, Brodahl U, Endresen K, Kristoffersen DT, Laake B, Simonsen S, Tofte AJ, Lundby B. Iodixanol in cardioangiography in patients with coronary artery disease. Tolerability, cardiac and renal effects. Acta Radiol. 1993;34:72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wessely R, Koppara T, Bradaric C, Vorpahl M, Braun S, Schulz S, Mehilli J, Schömig A, Kastrati A. Contrast Media and Nephrotoxicity Following Coronary Revascularization by Angioplasty Trial Investigators: Choice of contrast medium in patients with impaired renal function undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:430–437. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.874933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laskey W, Aspelin P, Davidson C, Rudnick M, Aubry P, Kumar S, Gietzen F, Wiemer M. Nephrotoxicity of iodixanol versus iopamidol in patients with chronic kidney disease and diabetes mellitus undergoing coronary angiographic procedures. Am Heart J. 2009;158:822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldkamp T, Baumgart D, Elsner M, Herget-Rosenthal S, Pietruck F, Erbel R, Philipp T, Kribben A. Nephrotoxicity of iso-osmolar versus low-osmolar contrast media is equal in low risk patients. Clin Nephrol. 2006;66:322–330. doi: 10.5414/cnp66322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juergens CP, Winter JP, Nguyen-Do P, Lo S, French JK, Hallani H, Fernandes C, Jepson N, Leung DY. Nephrotoxic effects of iodixanol and iopromide in patients with abnormal renal function receiving N-acetylcysteine and hydration before coronary angiography and intervention: a randomized trial. Intern Med J. 2009;39:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y-H, Zhang L-L, Zhou C-Y. Influences of an iso-osmolar versus a low-osmolar contrast media on radiographic contrast nephropathy in high-risk patients. J Clin Rehab Tissue Eng Res. 2008;12:683–686. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nie B, Cheng WJ, Li YF, Cao Z, Yang Q, Zhao YX, Guo YH, Zhou YJ. A prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial on the efficacy and cardiorenal safety of iodixanol vs. iopromide in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing coronary angiography with or without percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:958–965. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernández F, Mora L, García-Tejada J, Velázquez M, Gómez-Blázquez I, Bastante T, Albarrán A, Andreu J, Tascón J. Comparison of iodixanol and ioversol for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in diabetic patients after coronary angiography or angioplasty. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62:1373–1380. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)73531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jo SH, Youn TJ, Koo BK, Park JS, Kang HJ, Cho YS, Chung WY, Joo GW, Chae IH, Choi DJ, Oh BH, Lee MM, Park YB, Kim HS. Renal toxicity evaluation and comparison between Visipaque (iodixanol) and Hexabrix (ioxaglate) in patients with renal insufficiency undergoing coronary angiography: the RECOVER study: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:924–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehran R, Nikolsky E, Kirtane AJ, Caixeta A, Wong SC, Teirstein PS, Downey WE, Batchelor WB, Casterella PJ, Kim YH, Fahy M, Dangas GD. Ionic low-osmolar versus nonionic iso-osmolar contrast media to obviate worsening nephropathy after angioplasty in chronic renal failure patients: the ICON (Ionic versus non-ionic Contrast to Obviate worsening Nephropathy after angioplasty in chronic renal failure patients) study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolehmainen H, Soiva M. Comparison of Xenetix 300 and Visipaque 320 in patients with renal failure. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(suppl):B32–B33. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuang FR, Chen TC, Wang IK, Chuang CH, Chang HW, Ting-Yu Chiou T, Cheng YF, Lee WC, Chen WC, Yang KD, Lee CH. Comparison of iodixanol and iohexol in patients undergoing intravenous pyelography: a prospective controlled study. Ren Fail. 2009;31:181–188. doi: 10.1080/08860220802669636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, Erley CM, Grazioli L, Bonomo L, Ni Z, Romano L. The ACTIVE Trial: comparison of the effects on renal function of iomeprol-400 and iodixanol-320 in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing abdominal computed tomography. Invest Radiol. 2008;43:170–178. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31815f3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischbach R, Landwehr P, Lackner K, Nossen JO, Heindel W, Berg KJ, Eichhorn G, Jacobsen TF. Iodixanol vs iopamidol in intravenous DSA of the abdominal aorta and lower extremity arteries: a comparative phase-III trial. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:9–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00619943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuhn MJ, Chen N, Sahani DV, Reimer D, van Beek EJ, Heiken JP, So GJ. The PREDICT study: a randomized double-blind comparison of contrast-induced nephropathy after low- or isoosmolar contrast agent exposure. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:151–157. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen SA, Suranyi P, Ravenel JG, Randall PK, Romano PB, Strom KA, Costello P, Schoepf UJ. Iso-osmolality versus low-osmolality iodinated contrast medium at intravenous contrast-enhanced CT: effect on kidney function. Radiology. 2008;248:97–105. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrett BJ, Katzberg RW, Thomsen HS, Chen N, Sahani D, Soulez G, Heiken JP, Lepanto L, Ni ZH, Nelson R. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing computed tomography: a double-blind comparison of iodixanol and iopamidol. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:815–821. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000242807.01818.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Treitl M, Rupprecht H, Wirth S, Korner M, Reiser M, Rieger J. Assessment of renal vasoconstriction in vivo after intra-arterial administration of the isosmotic contrast medium iodixanol compared to the low-osmotic contrast medium iopamidol. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1478–1485. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen SL, Zhang J, Yei F, Zhu Z, Liu Z, Lin S, Chu J, Yan J, Zhang R, Kwan TW. Clinical outcomes of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective, multicenter, randomized study to analyze the effect of hydration and acetylcysteine. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, King SB, Anderson JL, Antman EM, et al. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2205–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudnick MR, Kesselhaim A, Goldfarb S. Contrast-induced nephropathy: how it develops, how to prevent it. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:75–86. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.73.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fried LF, Shlipak MG, Crump C, Bleyer AJ, Gottdiener JS, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Newman AB. Renal insufficiency as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in elderly individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1364–1372. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shulman NB, Ford CE, Hall WD, Blaufox MD, Simon D, Langford HG, Schneider KA. Prognostic value of serum creatinine and effect of treatment of hypertension on renal function. Results from the hypertension detection and follow-up program. The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Hypertension. 1989;13(5 suppl):I80–I93. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.5_suppl.i80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]