In the silkworm, Bombyx mori, the W chromosome plays a dominant role in female determination. However, neither protein-coding genes nor transcripts have so far been isolated from the W chromosome. Instead, a large amount of functional transposable elements and their remnants are accumulated on the W chromosome. PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are 23–30-nt-long small RNAs that potentially act as sequence-specific guides for PIWI proteins to silence transposon activity in animal gonads. In this study, by comparing ovary- and testis-derived piRNAs, numerous female-enriched piRNAs were identified. The data indicated that female-enriched piRNAs are derived from the W chromosome. Accordingly, these analyses reveal that the silkworm W chromosome is a source of piRNAs.

Keywords: silkworm, piRNA, sex chromosome, transposon

Abstract

In the silkworm, Bombyx mori, the W chromosome plays a dominant role in female determination. However, neither protein-coding genes nor transcripts have so far been isolated from the W chromosome. Instead, a large amount of functional transposable elements and their remnants are accumulated on the W chromosome. PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are 23–30-nt-long small RNAs that potentially act as sequence-specific guides for PIWI proteins to silence transposon activity in animal gonads. In this study, by comparing ovary- and testis-derived piRNAs, we identified numerous female-enriched piRNAs. Our data indicated that female-enriched piRNAs are derived from the W chromosome. Moreover, comparative analyses on piRNA profiles from a series of W chromosome mutant strains revealed a striking enrichment of a specific set of transposon-derived piRNAs in the putative sex-determining region. Collectively, we revealed the nature of the silkworm W chromosome as a source of piRNAs.

INTRODUCTION

In the silkworm, Bombyx mori, females are heterogametic (ZW), while males are homogametic (ZZ) (Fujii and Shimada 2007; Traut et al. 2007). In contrast to Drosophila (Casper and Van Doren 2006; Erickson and Quintero 2007; Salz and Erickson 2010), B. mori sex is strongly controlled by the W chromosome. It has been genetically shown that at least one copy of the W chromosome is sufficient for determining femaleness, irrespective of the Z chromosome copy number (Hashimoto 1933; Tajima 1944). This originally led to the simple assumption that the W chromosome encodes a female-determining gene(s). However, to date, no female-determining gene or even a single protein-coding gene has been isolated from the W chromosome. Moreover, no W chromosome-derived transcripts have been identified. Instead, there is compelling evidence that the W chromosome of B. mori harbors numerous transposable elements, their remnants, and simple repeats (Sahara et al. 2003; Abe et al. 2005; Yoshido et al. 2005; Fujii and Shimada 2007). Extensive fluorescence in situ hybridization studies have revealed that W chromosome-like sequences are dispersed on autosomes, reflecting the nature of transposable elements (Sahara et al. 2003; Yoshido et al. 2005). In addition, known bacterial artificial clone (BAC) sequences originating from the W chromosome contain only what appear to be transposable elements and their remnants (Abe et al. 2005). Interestingly, there are many more full-length copies of transposable elements on the W chromosome compared with autosomes. Moreover, all W chromosome-specific randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers identified to date have turned out to be truncated transposons (Abe et al. 2005).

Expansion of transposable elements in gonadal germline cells is quite dangerous for the host, because transposition-mediated mutations could be transmitted to the next generation (Klattenhoff and Theurkauf 2008; Ghildiyal and Zamore 2009; Malone and Hannon 2009). To avoid this, organisms have evolved a small RNA-mediated immunity against transposons. At the core of this immune system are PIWI proteins and associated PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs). piRNAs are 23–30-nt-long small RNAs that potentially act as sequence-specific guides for PIWI proteins (Klattenhoff and Theurkauf 2008; Ghildiyal and Zamore 2009; Malone and Hannon 2009). Mutations in PIWI proteins cause mobilization of transposons and result in severe defects in germline development (Klattenhoff and Theurkauf 2008; Ghildiyal and Zamore 2009; Malone and Hannon 2009). The piRNA production pathway is unique in that it does not require Dicer (Vagin et al. 2006; Houwing et al. 2007). piRNAs are born single-stranded and generated through 3′-to-5′ exonucleolytic trimming (Kawaoka et al. 2011a). It is proposed that slicer activity of PIWI proteins contributes to piRNA amplification (Brennecke et al. 2007; Gunawardane et al. 2007). The fly genome encodes the three PIWI proteins: Piwi, Aubergine (Aub), and Argonaute3 (Ago3). In the proposed model for piRNA production, the so-called ping-pong amplification cycle, Aubergine/antisense, “primary” piRNA complexes slice sense transposon mRNAs to generate sense “secondary” piRNAs, that are incorporated into Ago3 (Brennecke et al. 2007; Gunawardane et al. 2007). In turn, Ago3/sense, “secondary” piRNA complexes cleave antisense transcripts from defective transposon clusters, resulting in “secondary” antisense piRNAs. Therefore, euchromatic, functional copy-derived sense mRNAs are essential for this amplification (Brennecke et al. 2008; Chambeyron et al. 2008). In addition, our recent study showed that zygotic expression of sense transposon RNA is tightly coupled with ping-pong amplification after zygotic genome activation during silkworm embryogenesis (Kawaoka et al. 2011b). Heterochromatic dual-strand clusters, which express piRNAs from both strands, could operate the ping-pong cycle via a heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), a Rhino-mediated mechanism (Klattenhoff et al. 2009). Ping-pong amplification of piRNAs is conserved across phyla, including mice, zebrafish, and silkworm (Aravin et al. 2008; Houwing et al. 2008; Kawaoka et al. 2009, 2011b).

In this study, we characterized silkworm ovarian- and testis-derived piRNAs to identify sex dimorphic piRNA profiles. We identified numerous piRNAs that are more abundant in the ovary than in the testis and obtained evidence in many places that the silkworm W chromosome is a source of female-enriched piRNAs.

RESULTS

piRNA sex dimorphism in the silkworm gonads

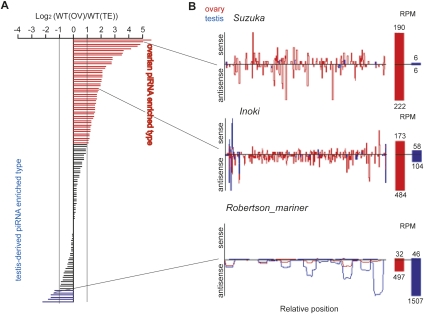

To address if the difference in sex chromosome constitution affects piRNA profiles, we analyzed piRNA libraries from total RNAs of wild-type (WT) Day 4 pupal ovaries and testes [WT(OV) and WT(TE), respectively]. The length distribution and nucleotide composition of ovarian- and testis-derived small RNAs were very similar to the characteristics of piRNAs cloned in other organisms (Supplemental Fig. S1). Next, we mapped the cloned reads to the two sets of silkworm transposable elements: 121 well-annotated transposable elements (or partial sequences) and the total set of 1668 transposons and simple repeats (ReAS clones) that were computationally identified from the B. mori genome (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Figs. S2, S3; International Silkworm Genome Consortium 2008; Osanai-Futahashi et al. 2008). In the rest of this study, piRNAs are referred to as 23–30-nt small RNAs that match transposons. For each transposon, we calculated the WT(OV)/WT(TE) ratio based on the normalized ovarian piRNA reads and normalized testis-derived piRNA reads (for normalization, see Materials and Methods). As a result, we found that 587 sequences, >30% of the total 1789 repeat sequences, exhibited WT(OV)/WT(TE) > 2 (Fig. 1A). As exemplified in Figure 1B, Suzuka-derived piRNAs were 31 times more abundant in ovaries than in testes (Fig. 1B). Among the 121 annotated transposons, the strongest bias was observed for Pakurin [WT(OV)/WT(TE) = 78]. On the other hand, relatively few transposons (122/1786, ∼8%) contained more testis-derived piRNAs than ovarian piRNAs [WT(OV)/WT(TE) < 0.5] (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S3). Robertson_mariner is a representative of this class (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

piRNA sex dimorphism in the silkworm. (A) Log2 fold ratio between normalized ovarian and testis-derived piRNA reads against 121 well-annotated transposons. (Red bars) Transposons showing higher content of ovarian piRNAs [WT(OV)/WT(TE) > 2]. (Blue bars) Transposon showing WT(TE)/WT(OV) > 2. (B) Density plots for representative transposons that show sex-biased piRNA content. Ovarian piRNAs (red); testis-derived piRNAs (blue). Normalized reads are indicated in reads per million (RPM).

Next, we analyzed individual piRNAs that uniquely matched 121 transposons, and found that 22,453 of 29,822 species of ovarian transposon-derived piRNAs were not sequenced in the testis-derived library. We confirmed female-enriched expression for a set of piRNAs by quantitative PCR (qPCR). qPCR data clarified the existence of female-enriched piRNAs (Supplemental Fig. S4).

W chromosome is a source of female-enriched piRNAs

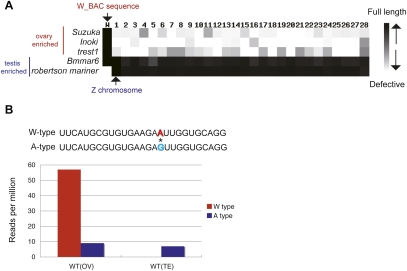

To determine where such marked differences come from, the genomic origin of each sequence was ascertained using the current B. mori genome data (International Silkworm Genome Consortium 2008) and several W chromosome-derived BAC sequences (W-BAC; see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 2A). We found that full-length copies of transposons exhibiting WT(OV)/WT(TE) > 2 are often located only on the W chromosome, but remnants of these transposons are found throughout autosomes (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, previous studies demonstrated that the W chromosome shares many sequences with autosomes, reflecting the nature of transposons (Sahara et al. 2003; Yoshido et al. 2005). Realizing these facts, we tried to identify piRNAs unique to the W chromosome. Our detailed analyses identified a set of female-enriched piRNAs that perfectly matched to W-BAC sequences, but not to autosomal loci (Fig. 2B, 2027 species, one mismatch to autosomes). This suggested that the W chromosome actually expresses female-enriched piRNAs.

FIGURE 2.

The W chromosome is a source of female-enriched piRNAs. (A) Chromosomal distribution of indicated transposons. We mapped indicated transposons to the B. mori genome and W-BAC sequences using BLAST. Color intensity indicates the maximum length of the mapped transposon (E-value < 1 × 10−50). (B) Single nucleotide polymorphism between W chromosome-derived piRNA (W-type) and autosomal piRNA (A-type). Expression levels (RPM) of each type of piRNA in ovarian and testis-derived libraries are shown.

Ping-pong signatures (see Materials and Methods) of piRNAs from transposons showing WT(OV)/WT(TE) > 2 were often detected at statistically significant levels in the ovary but not in the testis (Supplemental Table S1), suggesting that female-enriched piRNAs might be generated via PIWI-mediated cleavage. In addition, male-enriched piRNAs showed statistically significant ping-pong signatures as well. A full-length copy of Robertson_mariner, which showed WT(OV)/WT(TE) < 0.5, was located on the Z chromosome (Figs. 1, 2). Because males have two Z chromosomes and females only have one Z chromosome, it is likely that the additional copy of Z chromosome affects male piRNA profiles.

How does the W chromosome contribute to female-enriched piRNA production? We hypothesized two possibilities. One is that the W chromosome may provide sense transposon mRNAs, which are the possible substrates for antisense piRNAs from autosomal defective transposon clusters, to produce sense female-enriched piRNAs. Another possibility is that the W chromosome harbors both functional and defective copies of transposons or simply acts as large heterochromatic dual-strand clusters (Klattenhoff et al. 2009), producing both sense and antisense piRNAs. To address these possibilities, we calculated the ratio between normalized ovarian piRNA reads and normalized testis-derived piRNA reads in sense orientation [WT(OV)sense/WT(TE)sense] and in antisense orientation [WT(OV)antisense/WT(TE)antisense]. As shown in Supplemental Table S2, our analysis supported both possibilities. As represented by W-Sasuke [WT(OV)sense/WT(TE)sense = 3.6 and WT(OV)antisense/WT(TE)antisense = 1.4], we found transposons whose sense piRNAs were selectively increased in the ovary. At the same time, in the case of transposons such as SART1 [WT(OV)sense/WT(TE)sense = 4.1 and WT(OV)antisense/WT(TE)antisense = 4.3], both sense and antisense piRNAs were increased in the ovary.

piRNAs deriving from sex-determining region

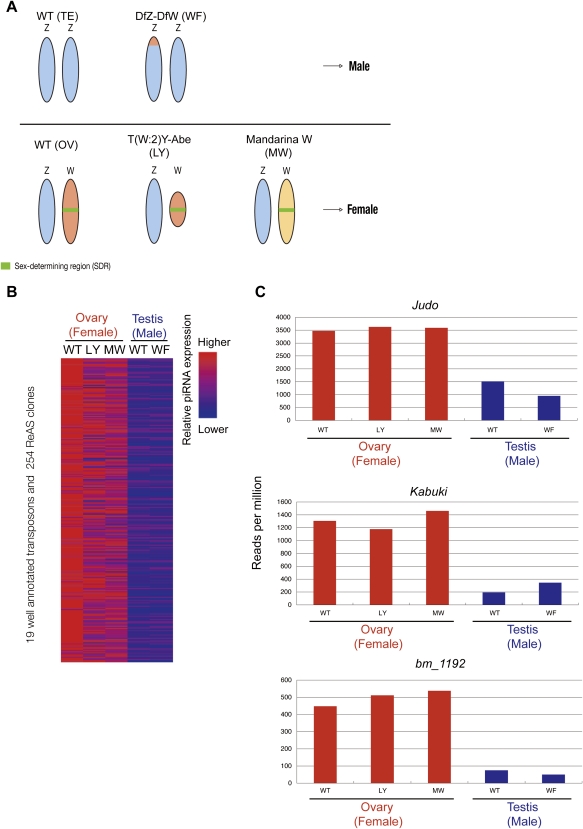

Comparison between ovarian- and testis-derived piRNAs allowed us to deduce if a full-length transposon is located on the W chromosome, even though the entire sequence of the W chromosome has not been determined due to its repetitive nature (see Materials and Methods). Taking advantage of this piRNA-based approach, we wanted to extend our analysis to the putative sex-determining region (SDR) of the W chromosome. To this end, we used the three W chromosome mutants each featuring a unique W chromosome with concomitant distinct sex determination (Fig. 3A). Sex-limited yellow [T (W:2)Y-Abe; called LY] was established by X-ray-mediated mutagenesis (Abe et al. 2008). The W chromosome of LY lacks a large part of the W chromosome corresponding to 11 of the 12 known W chromosome-specific RAPD markers, and its size was estimated to be one-tenth that of the wild-type W chromosome. Despite its small size, the LY W chromosome retains the ability to determine femaleness. On the other hand, the part of the W chromosome corresponding to three RAPD markers is attached to the Z chromosome of the strain DfZ-DfW (called “without Fem,” WF) (Fujii et al. 2006). Genetic studies demonstrated that this Z chromosome-attached W chromosome fragment is insufficient for determining femaleness, indicating that this fragment does not cover the SDR. Another possibility is that there is a redundant SDR in these fragments, but that it is not transcribed because it is attached to the Z chromosome. Additionally, we used a newly established introgression line, named Mandarina W (MW), which harbors the W chromosome from Bombyx mandarina, a supposed ancient species of B. mori. B. mori can be crossed with B. mandarina to produce fertile hybrids, even though the total chromosome number is different between these two species (B. mori: n = 28; Japanese B. mandarina: n = 27). The B. mandarina W chromosome, which is also known to be transposon-rich (Abe et al. 1998, 2002), can determine the femaleness of B. mori, suggesting that female determinants are common between B. mori and B. mandarina.

FIGURE 3.

Transposons and associated piRNAs derived from the sex-determining region. (A) Strains with several types of W chromosomes. LY's W chromosome lacks 11 of 12 known W chromosome-specific RAPD markers, but it retains the sex-determining ability. MW is an introgression line that harbors W chromosome of B. mandarina (see text), which can determine the sex of B. mori. The W chromosome fragment attached to the Z chromosome cannot determine femaleness. (B) Transposons enriched in the sex-determining region. The heat map indicates relative expression of piRNAs from five libraries matching each transposon (Supplemental Table S4). (C) Representative transposons enriched in the sex-determining region (SDR).

Given that genomic distributions of transposons could be inferred from piRNA expression data, comparison of piRNA profiles from these three strains may enable identification of transposons and associated piRNAs deriving from the SDR. For this purpose, two piRNA libraries from LY and MW ovaries of Day 4 pupa [LY(OV) and MW(OV), respectively] and one testis-derived library from WF testis of Day 4 pupa [WF(TE)] were constructed and analyzed (Supplemental Fig. S5). To search for transposons and associated piRNAs potentially deriving from the SDR, we considered the following criteria by normalizing each library with the number of genome-mapping reads: (1) a transposon contains more WT ovarian piRNAs than WT testis-derived piRNAs [WT(OV)/WT(TE) > 2]; (2) a transposon whose piRNA profile is comparable among WT, LY, and MW ovaries [0.5 < WT(OV)/LY(OV), WT(OV)/MW(OV)]; and (3) a transposon whose piRNA profile is conserved between WT and WF testes [0.5 < WT(TE)/WF(TE) < 2 and WT(OV)/WF(TE) > 2]. We found that 273 sequences satisfied these criteria (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Table S3). For instance, 3469 reads per million (RPM) of WT ovarian piRNAs matched Judo, while 3627 and 3590 RPM from LY and MW matched Judo, respectively (Fig. 3C). The abundance of Judo-derived piRNAs was very similar between WT and WF testes, suggesting that functional copies of Judo are missing in the WF's W chromosome fragment. Collectively, active full-length Judo is seemingly enriched in the SDR. We examined the expression levels of individual Judo-derived piRNAs by qPCR and confirmed that a set of piRNAs was, indeed, enriched in the SDR (Supplemental Fig. S6). piRNA profiles on 121 annotated transposons were quite similar between WT ovarian piRNAs and MW ovarian piRNAs [107/121 transposons showed 0.5 < WT(OV)/MW(OV) < 2] (data not shown). In contrast, the WF W chromosome largely affects piRNA profiles [30/121 showed WF(TE)/WT(TE) > 2], indicating that at least a part of the translocated W chromosome fragment is actually transcribed. Collectively, our present analysis revealed a striking enrichment of a specific set of transposons and associated piRNAs in the SDR of the W chromosome.

DISCUSSION

The nature of the silkworm's W chromosome, which is a strong determinant for femaleness, has been a long-standing mystery. Here we uncovered that the W chromosome expresses numerous female-enriched piRNAs.

Comparison between ovarian- and testis-derived piRNAs identified many piRNAs that are more abundant in the ovary than in the testis (Fig. 1; Supplemental Figs. S2, S3). These piRNAs are likely derived from the W chromosome (Fig. 2). Importantly, ping-pong signatures of piRNA sets from transposons that were more abundant in the ovary than in the testis [WT(OV)/WT(TE) > 2] were often detected at statistically significant levels in the ovary but not in the testis (Supplemental Table S1). Because ping-pong signatures are signs for PIWI-mediated piRNA production, these results suggest that female-enriched piRNAs are generated via PIWI-mediated cleavage. Pakurin-derived piRNAs were much less abundant in the testis than in the ovary but still retain their ping-pong signature in the testis. In such a case, autosomes may have minimal sets of sequences for ping-pong amplification, which are at the same time quantitatively not sufficient to produce piRNAs at the abundance observed in the ovary.

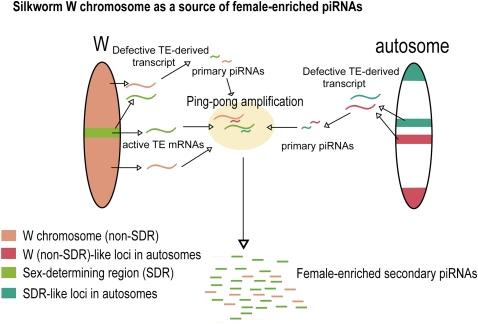

W chromosome-dependent ping-pong amplification in the ovary may occur in two different ways (Fig. 4). In one case, as represented by W-Sasuke, the W chromosome expresses sense transposon mRNAs, which are cleaved by antisense piRNAs from autosomal defective transposon clusters, to generate female-enriched secondary sense piRNAs (Supplemental Table S2). Supporting this idea, previous studies implied that sense transposon mRNAs are likely to be essential for ping-pong amplification in flies and silkworm (Brennecke et al. 2007, 2008; Gunawardane et al. 2007; Chambeyron et al. 2008; Kawaoka et al. 2011b). In another case, the W chromosome harbors both functional and defective copies of transposons or behaves as heterochromatic dual-strand clusters (Klattenhoff et al. 2009) to produce both sense and antisense piRNAs. SART1-derived piRNAs are representative of this class (Supplemental Table S2). Collectively, the W chromosome amplifies production of both sense and antisense piRNAs.

FIGURE 4.

The nature of the silkworm W chromosome as a source of female-enriched piRNAs. The silkworm W chromosome contributes to production of female-enriched piRNAs. Primary piRNAs can be produced from defective transposon loci in the W chromosome and autosomes. Female-enriched secondary piRNAs can be generated through cleavage of W chromosome-derived sense transposon mRNAs by such primary piRNAs. Female-enriched piRNAs such as Pakurin-derived piRNAs can be produced both from SDR and non-SDR loci in the W chromosome. A set of female-enriched piRNAs such as Judo-derived piRNAs shows a striking enrichment in the SDR.

A piRNA-based dissection on a series of W chromosome mutants (Fig. 3A) revealed that a specific set of transposons and associated piRNAs was enriched in the putative sex-determining region (SDR-related transposons and piRNAs), suggesting a biased localization of particular transposons such as Judo within the W chromosome (Fig. 3; Supplemental Fig. S6; Supplemental Table S3). In contrast, while Pakurin showed maximum WT(OV)/WT(TE), Pakurin-derived piRNAs were not likely enriched in the SDR, indicating that Pakurin may be widely distributed throughout the W chromosome. It is evolutionarily important that the W chromosome from B. mandarina did not strongly affect piRNA profile. Therefore, based on their respective piRNA profiles, we can infer that the transposon composition on the W chromosome should be similar between B. mori and B. mandarina. These results indicate that our piRNA-based approach would be a powerful tool to analyze a highly repetitive chromosome of nonmodel organisms.

In summary, our present study revealed the W chromosome as a source of female-enriched piRNAs (Fig. 4). Understanding of a role of these female-enriched piRNAs awaits further investigation. We are presently analyzing piRNA profiles from a newly obtained W chromosome mutant, which shows masculinized phenotypes specifically in females. This would contribute to clarification of a role for female-enriched piRNAs in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. mori strains

Wild-type (WT; n = 28) strain p50T, T(W:2)Y-Abe (LY) (Abe et al. 2008), and DfZ-DfW (WF) (Fujii et al. 2006) were reared on fresh mulberry leaves in an insect rearing chamber under short-day conditions (12L: 12D). An introgression line between B. mori and B. mandarina, named MW, harbors the B. mandarina W chromosome. To construct the MW line, we paired a female moth of B. mandarina (n = 27) collected from Saitama prefecture, Japan, with a male of p50T. The resulting F1 females were paired with males of the p50T strain. Thus, the W chromosome of B. mandarina was maintained by repeatedly backcrossing (five times) the females to p50T males.

piRNA library construction

Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The total RNA (10 μg) was loaded onto a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea, electrophoresed, and then stained with SYBRGold (Invitrogen). Signals were visualized using LAS-1000 film (Fujifilm). Because silkworm piRNAs are visible as a distinct band by SYBRGold staining, we could easily gel-purify the piRNA-containing fraction. Small RNA libraries were constructed using a small RNA cloning kit (Takara). DNA sequencing was performed using the Solexa genetic analysis system (Illumina) (Kawaoka et al. 2009). One nanogram of the prepared cDNA was used for the sequencing reactions with the Illumina GA. Ten thousand to 15,000 clusters were generated per “tile,” and 36 cycles of the sequencing reactions were performed. The protocols of the cluster generation and sequence reactions were according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequence analysis

Solexa sequencing generated reads of up to 36 nt in length. The 3′-adaptor sequences were identified and removed, allowing for up to two mismatches. Reads without adaptor sequences were discarded. Reads shorter than 23 nt or longer than 30 nt were excluded, resulting in reads of 23–30 nt. Alignments to the B. mori genome (International Silkworm Genome Consortium 2008), 121 annotated transposons, and 1668 ReAS clones (Osanai-Futahashi et al. 2008) were performed with SOAP2 (ver. 2.20) allowing no mismatch (Li et al. 2009). The total number of perfect genome-mapping reads reflects the sequencing depth. To compare the reads among different data sets, reads were expressed in reads per million (RPM) by normalizing to the total number of perfect genome mapping in each library.

Ping-pong signature

Ping-pong significance was tested as described previously (Kawaoka et al. 2011b). Ping-pong pairs were defined as precise 10-nt overlaps between sense and antisense piRNAs matching each of the 121 transposons. The observed abundance of ping-pong pairs (O) was defined as the sum of all of the piRNA reads that joined in ping-pong pairs. For estimating the expectation (E), we counted how many piRNA reads form ping-pong pairs when we randomly map the n number of antisense piRNAs and the m number of sense piRNAs to each transposons. By computing this process 100,000 times for each transposon, we calculated the score X = (O − Ei) (i = 1, 2, …, 100,000). The P-value represents k/100,000, where k shows how many times X meets (O − Ei) < 0. The R-code for this analysis will be provided upon request.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Small RNA fractions were enriched with the aid of the miRVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty nanograms of purified RNAs were reverse-transcribed by using the miScript Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN), and synthesized cDNA was analyzed by the miScript PCR System (QIAGEN). qPCR was carried out with 2× Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), and the amplification was detected using the ABI StepOne and StepOne Plus Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers used in this experiment are described in Supplemental Table S4. This method, similar to Northern blotting, cannot discriminate the 3′-end heterogeneity generally observed in piRNAs.

W chromosome bacterial artificial clone (BAC) sequence

Besides publicly available W-BAC sequences, we obtained new sets of W-BAC sequences. W-BAC sequences were screened, identified, sequenced, and assembled as described previously (Abe et al. 2008). Newly identified W-BAC sequences seemed not to encode any protein-coding genes. The average length of available BAC sequences was 1275 nt. Thus, because full lengths of many transposons are more than several thousand nucleotides, it is difficult to infer whether a full length of transposon is located on the W chromosome. We could safely judge whether a full-length transposon is located on the W chromosome only when a BAC clone is long enough and contains a transposon of an interest. In this respect, our analysis was limited to a specific set of transposons.

Detailed mapping data

Detailed mapping data of piRNAs to each transposons are summarized in Excel format as exemplified in Supplemental Table S5. Full data sets will be provided upon request.

Data deposition

piRNAs sequenced in this study are deposited in DRA000173. W-BAC sequences in this study were submitted to the DNA database of Japan under accession numbers BABU01000001–BABU01000479.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank N. Hayashi for preliminary analysis, T. Kawamata and P. B. Kwak for critical comments on the manuscript, and M. Kawamoto and E. Sekimori for their technical assistance. Sh.K. is a recipient of a fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. This work was supported in part by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of the Japanese Government (MEXT) (No. 22115502 to Su.K.; No. 21710208 to K.K.; No. 17018007 to T.S.; and the Professional Program for Agricultural Bioinformatics) and by the National Bio-Resource Project “Silkworm” of MEXT, and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (“Functional machinery for non-coding RNAs”) to Su.K. and Y.T.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.027565.111.

REFERENCES

- Abe H, Kanehara M, Terada T, Ohbayashi F, Shimada T, Kawai S, Suzuki M, Sugasaki T, Oshiki T 1998. Identification of novel random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs) on the W chromosome of the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori, and the wild silkworm, B. mandarina, and their retrotransposable element-related nucleotide sequences. Genes Genet Syst 73: 243–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe H, Sugasaki T, Terada T, Kanehara M, Ohbayashi F, Shimada T, Kawai S, Mita K, Oshiki T 2002. Nested retrotransposons on the W chromosome of the wild silkworm Bombyx mandarina. Insect Mol Biol 11: 307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe H, Mita K, Yasukochi Y, Oshiki T, Shimada T 2005. Retrotransposable elements on the W chromosome of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Cytogenet Genome Res 110: 144–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe H, Fujii T, Tanaka N, Yokoyama T, Kakehashi H, Ajimura M, Mita K, Banno Y, Yasukochi Y, Oshiki T, et al. 2008. Identification of the female-determining region of the W chromosome in Bombyx mori. Genetica 133: 269–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Bourc'his D, Schaefer C, Pezic D, Toth KF, Bestor T, Hannon GJ 2008. A piRNA pathway primed by individual transposons is linked to de novo DNA methylation in mice. Mol Cell 31: 785–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Aravin AA, Stark A, Dus M, Kellis M, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ 2007. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell 128: 1089–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Malone CD, Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Stark A, Hannon GJ 2008. An epigenetic role for maternally inherited piRNAs in transposon silencing. Science 322: 1387–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper A, Van Doren M 2006. The control of sexual identity in the Drosophila germline. Development 133: 2783–2791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambeyron S, Popkova A, Payen-Groschene G, Brun C, Laouini D, Pelisson A, Bucheton A 2008. piRNA-mediated nuclear accumulation of retrotransposon transcripts in the Drosophila female germline. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 14964–14969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JW, Quintero JJ 2007. Indirect effects of ploidy suggest X chromosome dose, not the X:A ratio, signals sex in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 5: e332 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T, Shimada T 2007. Sex determination in the silkworm, Bombyx mori: A female determinant on the W chromosome and the sex-determining gene cascade. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18: 379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T, Tanaka N, Yokoyama T, Ninaki O, Oshiki T, Ohnuma A, Tazima Y, Banno Y, Ajimura M, Mita K, et al. 2006. The female-killing chromosome of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, was generated by translocation between the Z and W chromosomes. Genetica 127: 253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD 2009. Small silencing RNAs: An expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet 10: 94–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardane LS, Saito K, Nishida KM, Miyoshi K, Kawamura Y, Nagami T, Siomi H, Siomi MC 2007. A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5′ end formation in Drosophila. Science 315: 1587–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H 1933. The role of the W-chromosome in the sex determination of Bombyx mori. Jpn J Genet 8: 245–247 [Google Scholar]

- Houwing S, Kamminga LM, Berezikov E, Cronembold D, Girard A, van den Elst H, Filippov DV, Blaser H, Raz E, Moens CB, et al. 2007. A role for Piwi and piRNAs in germ cell maintenance and transposon silencing in zebrafish. Cell 129: 69–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houwing S, Berezikov E, Ketting RF 2008. Zili is required for germ cell differentiation and meiosis in zebrafish. EMBO J 27: 2702–2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Silkworm Genome Consortium. 2008. The genome of a lepidopteran model insect, the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 38: 1036–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaoka S, Hayashi N, Suzuki Y, Abe H, Sugano S, Tomari Y, Shimada T, Katsuma S 2009. The Bombyx ovary-derived cell line endogenously expresses PIWI/PIWI-interacting RNA complexes. RNA 15: 1258–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaoka S, Izumi N, Katsuma S, Tomari Y 2011a. 3′ end formation of PIWI-interacting RNAs in vitro. Mol Cell 43: 1015–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaoka S, Arai Y, Kadota K, Suzuki Y, Hara K, Sugano S, Simizu K, Tomari Y, Shimada T, Katsuma S 2011b. Zygotic amplification of secondary piRNAs during the silkworm embryogenesis. RNA 7: 1401–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf W 2008. Biogenesis and germline functions of piRNAs. Development 135: 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff C, Xi H, Li C, Lee S, Xu J, Khurana JS, Zhang F, Schultz N, Koppetsch BS, Nowosielska A, et al. 2009. The Drosophila HP1 homolog Rhino is required for transposon silencing and piRNA production by dual-strand clusters. Cell 138: 1137–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Yu C, Li Y, Lam TW, Yiu SM, Kristiansen K, Wang J 2009. SOAP2: An improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics 25: 1966–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Hannon GJ 2009. Molecular evolution of piRNA and transposon control pathways in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 74: 225–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai-Futahashi M, Suetsugu Y, Mita K, Fujiwara H 2008. Genome-wide screening and characterization of transposable elements and their distribution analysis in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 38: 1046–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara K, Yoshido A, Kawamura N, Ohnuma A, Abe H, Mita K, Oshiki T, Shimada T, Asano S, Bando H, et al. 2003. W-derived BAC probes as a new tool for identification of the W chromosome and its aberrations in Bombyx mori. Chromosoma 112: 48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salz HK, Erickson JW 2010. Sex determination in Drosophila: The view from the top. Fly (Austin) 4: 60–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima Y 1944. Studies on chromosome aberrations in the silkworm. II. Translocation involving second and W-chromosomes. Bull Seric Exp Stn 12: 109–181 [Google Scholar]

- Traut W, Sahara K, Marec F 2007. Sex chromosomes and sex determination in Lepidoptera. Sex Dev 1: 332–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin VV, Sigova A, Li C, Seitz H, Gvozdev V, Zamore PD 2006. A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science 313: 320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshido A, Bando H, Yasukochi Y, Sahara K 2005. The Bombyx mori karyotype and the assignment of linkage groups. Genetics 170: 675–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]