Abstract

Background

Many online physician-rating sites provide patients with information about physicians and allow patients to rate physicians. Understanding what information is available is important given that patients may use this information to choose a physician.

Objectives

The goals of this study were to (1) determine the most frequently visited physician-rating websites with user-generated content, (2) evaluate the available information on these websites, and (3) analyze 4999 individual online ratings of physicians.

Methods

On October 1, 2010, using Google Trends we identified the 10 most frequently visited online physician-rating sites with user-generated content. We then studied each site to evaluate the available information (eg, board certification, years in practice), the types of rating scales (eg, 1–5, 1–4, 1–100), and dimensions of care (eg, recommend to a friend, waiting room time) used to rate physicians. We analyzed data from 4999 selected physician ratings without identifiers to assess how physicians are rated online.

Results

The 10 most commonly visited websites with user-generated content were HealthGrades.com, Vitals.com, Yelp.com, YP.com, RevolutionHealth.com, RateMD.com, Angieslist.com, Checkbook.org, Kudzu.com, and ZocDoc.com. A total of 35 different dimensions of care were rated by patients in the websites, with a median of 4.5 (mean 4.9, SD 2.8, range 1–9) questions per site. Depending on the scale used for each physician-rating website, the average rating was 77 out of 100 for sites using a 100-point scale (SD 11, median 76, range 33–100), 3.84 out of 5 (77%) for sites using a 5-point scale (SD 0.98, median 4, range 1–5), and 3.1 out of 4 (78%) for sites using a 4-point scale (SD 0.72, median 3, range 1–4). The percentage of reviews rated ≥75 on a 100-point scale was 61.5% (246/400), ≥4 on a 5-point scale was 57.74% (2078/3599), and ≥3 on a 4-point scale was 74.0% (740/1000). The patient’s single overall rating of the physician correlated with the other dimensions of care that were rated by patients for the same physician (Pearson correlation, r = .73, P < .001).

Conclusions

Most patients give physicians a favorable rating on online physician-rating sites. A single overall rating to evaluate physicians may be sufficient to assess a patient’s opinion of the physician. The optimal content and rating method that is useful to patients when visiting online physician-rating sites deserves further study. Conducting a qualitative analysis to compare the quantitative ratings would help validate the rating instruments used to evaluate physicians.

Keywords: Doctor ratings, patient satisfaction, online physician reviews, consumer health, physician rating

Introduction

In 2010, 88% of adult Americans used the Internet to search for health-related information [1-3]. Patients are seeking information not only about disease conditions but also about physicians and hospitals. In fact, in the United States, 47% looked up information about their providers online, 37% consulted physician-rating sites, and 7% of people who sought information about their provider posted a review online [4]. A separate study found that 15% of consumers compare hospitals before making a selection, and 30% of consumers compare physicians online before making a selection [5].

Many physician-rating websites provide users with basic information about the physician such as years in practice and contact information [6,7]. Some of the websites access various databases to display further information about board certification, residency, and any disciplinary action [8]. This information can be obtained for free, or patients can pay to obtain a more in-depth report about the physician [9].

Many websites enable users to enter reviews and rankings about specific physicians. This capability has drawn the attention of consumer advocacy groups, providers, insurance companies, and hospitals. Although knowledge about the patient experience is useful, critics of these portals identify them as being at risk for misinformation, sabotage, and manipulation [10-14]. Few large-scale studies have been conducted to assess the content and rating methods of these physician-rating sites [15].

The goals of this study were to (1) determine the most frequently visited physician-rating websites that have user-generated content, (2) evaluate the content characteristics of each site to rate physicians, and (3) analyze online ratings of 4999 individual physician ratings.

Methods

Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University School of Medicine.

The Most Commonly Visited Physician-Rating Sites

A search of the Internet (Bing, Google, Google Directory, Google Trends, Blekko, Yahoo, and Yahoo Directory) with search terms doctor rating, physician rating, physician- rating, physician ranking, and quality physicians produced a list of physician-rating sites currently available in the United States [7,15]. On October 1, 2010, using Google Trends, we identified the most commonly visited physician-rating websites using the number of daily unique visits each website attracted [16,17]. Sites with fewer than 5000 daily unique visits as measured on Google Trends were not included in the analyses. Of note, Google Trends is not an absolute measure of Web traffic. The assumption was that the relative Web traffic volume relationship between different websites was consistent. Websites that had Web traffic that registered on Google Trends but did not allow for user-generated content were not included in the analyses. User-generated content was defined as the ability to rate or comment on the physician.

Rating Content Characteristics of Each Website

We then studied each site to determine the types of rating scales (eg, 1–5, 1–4, 1–100) used and dimensions of care rated (eg, recommend to a friend, waiting room time). All the dimensions of care were identified for each website. To compare different websites, we created a semantic normalization tool. A semantic conversion table was created by first identifying all the different dimensions of care used on each website (Table 1). To facilitate the analysis, each dimension was assigned to 5 categories by three individuals working independently. The 5 different categories were chosen based on the most prevalent rating categories present across various rating websites. There was agreement on 31 of the 35 items, and the group discussed the remaining 4 with the lead author until consensus was reached on the most appropriate category designation: overall rating, communication skills, access, facilities, and staff.

Table 1.

Semantic conversion table used to normalize different dimensions of care used to rate physicians on the websites

| Overall rating | Communication Skills | Access | Facilities | Staff |

| Overall | Communication | Appointments | Office cleanliness | Courteous staff |

| Level of trust | Explanation | Approachable | Office setting | Staff |

| Overall quality of care | Explanation of medications | Doctor availability | Office environment | Staff friendliness |

| Recommendation | Follow-up | Convenience | Service | Staff helpfulness |

| Recommend to a friend | Attentive during visit | Ease of appointment | Waiting room | Staff professionalism |

| Patient satisfaction | Listens and answers questions | Quality of referrals | Facilities | Office friendliness |

| Likely to recommend | Bedside manner | Make Referrals | ||

| Helps patient understand | Punctuality |

Analysis of Individual Physician Ratings

Raw data without specific physician identifiers were obtained in October, November, and December 2010 via a nonrandom selection of 4999 online physician ratings from 23 multiple specialties (allergy, cardiology, cardiothoracic surgery, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, general surgery, hematology, internal medicine, nephrology, neurology, neurosurgery, obstetrics and gynecology, oncology, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, pediatrics, plastic surgery, primary care, pulmonary medicine, rheumatology, and urology) in 25 metropolitan areas (Atlanta, GA; Austin, TX; Baltimore, MD; Boston, MA; Charlotte, NC; Chicago, IL; Colorado Springs, CO; Columbus, OH; Denver, CO; Houston, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Miami, FL; Minneapolis, MN; New Orleans, LA; New York City, NY; Orlando, FL; Phoenix, AZ; Portland, OR; Salt Lake City, UT; San Diego, CA; San Francisco, CA; Raleigh, NC; San Jose, CA; Seattle, WA; and Washington, DC). We chose these cities because they have the highest Internet usage and largest population in the United States [18-20]. The selection of physicians was nonrandom to avoid counting the same physician more than once.

The number of reviews collected from each website varied proportionally by how frequently the websites were visited based on Web traffic estimates from Google Trends. Therefore, the number of reviews from each website was proportional to Web traffic volume assuming that search patterns on Google are similar to those on other search engines.

The sequence of steps followed to acquire each physician rating was to visit the website, enter the city, choose a specialty, enter the largest search radius, and then sort physicians by name when possible. If sorting by name was not possible then location was used. Only reviews that had at least one physician rating completed by a patient within the years 2000–2010 were included in the analyses. Each analyst was assigned a set of metropolitan areas to evaluate physician data.

Cut-offs of 75 (100-point scale), 4 (5-point scale), and 3 (4-point scale) were used to define the favorable threshold for each category of physician-rating website. To compare rankings from different websites with the same rating system, we used a weighted average to accurately represent the overall compiled rating. Only physician-rating sites with the same rating system were compared with one another.

To facilitate analyses, similar dimensions of care—but with different terms used by each website—were grouped into 1 of the 5 categories defined above (overall rating, access, communication skills, facility, and staff). For example, wait time, waiting room time, waiting time, and punctuality were all grouped as part of access (Table 1).

Results

The Most Commonly Visited Physician-Rating Sites

The 10 most commonly visited online physician-rating websites with user-generated content per Google Trends were HealthGrades.com, Vitals.com, Yelp.com, YP.com, RevolutionHealth.com, RateMD.com, Angieslist.com, Checkbook.org, Kudzu.com, and ZocDoc.com (Table 2).

Table 2.

Top 10 most frequently visited physician-rating websites as a relative measure of Web traffic as measured through Google Trends (October-December 2010)

| Website | Percentage | Daily unique visits (per Google Trends) |

| HealthGrades | 40% | 254,600 |

| Vitals | 20% | 127,300 |

| Yelp | 15% | 95,475 |

| Checkbook | 7% | 44,555 |

| YP | 5% | 31,825 |

| ZocDoc | 4.8% | 30,552 |

| AngiesList | 3.2% | 20,368 |

| RateMD | 3% | 19,095 |

| RevolutionHealth | 1% | 6365 |

| Kudzu | 1% | 6365 |

| Total | 100% | 636,500 |

Content Characteristics of Each Website

Patients rated 35 different dimensions of care in the websites, with a median of 4.5 (mean 4.9, SD 2.8, range 1–9) dimensions of care per website (Table 1). There was a varying degree of information available on each physician-rating website. Some websites provide users with information on board certification. Some websites have advertisements and other websites provide users the ability to compare physicians side-by-side. Table 3 summarizes information, features, and the presence of advertisements on physician-rating websites.

Table 3.

Information available on the top 10 physician-rating sites

| Website | Comments | Board certification | Years in practice | Physician comparison | Advertising | Sanctions |

| RateMD | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Vitals | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AngiesList | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| HealthGrades | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| YP | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Kudzu | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Yelp | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| ZocDoc | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| CheckBook | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| RevolutionHealth | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

Analysis of Individual Physician Ratings

The average rating was 77 (308/400, 77.0%) for sites using a 100-point scale (SD 11, median 76, range 33–100). For sites using a 5-point scale the average rating was 3.84 (76.8%, 2764/3599, SD 0.98, median 4, range 1–5). For sites using a 4-point scale the average was 3.1 (77.5%, 774/1000, SD 0.72, median 3, range 1–4).

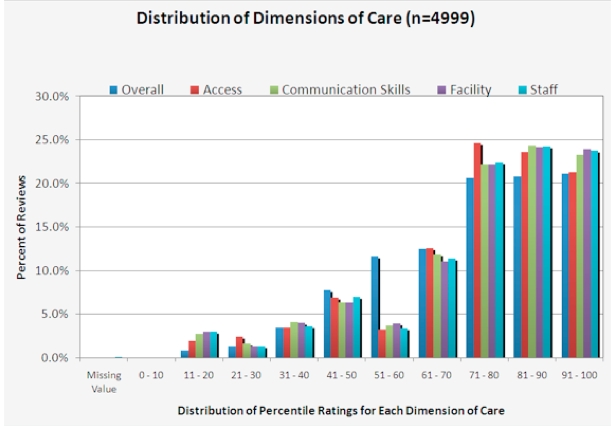

The percentage of reviews with a rating of 75 or higher on physician-rating sites with a 100-point scale was 61.5% (246/400). The percentage of reviews with a rating of 4 or higher on sites with a 5-point scale were 57.74% (2078/3599). The percentage of reviews with a rating of 3 or higher on sites with a 4-point scale were 74.0% (740/100) (Table 4 and Figure 1).

Table 4.

Physician ratings from the top 10 physician-rating websites with user-generated content. Percentage favorable ratings defined as ≥3 of 4, ≥4 of 5, or ≥75 of 100

| Website | Number of reviews evaluated |

Percentage of total |

Favorable reviews | Overall rating | Lowest rating |

Highest rating |

||||

| n | % | Mean | SD | Median | ||||||

| 100-Point scales | ||||||||||

| Checkbook.org/PatientCentral | 350 | 7% | 217 | 62 | 77.59 | 10.48 | 76.00 | 34.00 | 100.00 | |

| RevolutionHealth | 50 | 1% | 29 | 57 | 74.24 | 16.01 | 76.00 | 33.00 | 100.00 | |

| Weighted average | 400 | 8% | 246 | 62 | 77.17 | 11.17 | 76.00 | 33.00 | 100.00 | |

| 5-Point scales | ||||||||||

| AngiesList | 159 | 3% | 103 | 65 | 3.95 | 0.95 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| HealthGrades | 2000 | 40% | 1139 | 57 | 3.82 | 0.98 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| Kudzu | 49 | 1% | 26 | 53 | 3.74 | 0.96 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| RateMD | 150 | 3% | 87 | 58 | 3.84 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| Yelp | 750 | 15% | 442 | 59 | 3.86 | 0.97 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| YP | 250 | 5% | 158 | 63 | 3.93 | 0.92 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| ZocDoc | 241 | 5% | 123 | 51 | 3.77 | 0.92 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| Weighted average | 3599 | 72% | 2078 | 58 | 3.84 | 0.98 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| 4-Point scale | ||||||||||

| Vitals | 1000 | 20% | 740 | 74 | 3.10 | 0.72 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | |

| Total | 4999 | 100% | 3064 | 61.28 | ||||||

Figure 1.

Distribution of percentile ratings for each dimension of care rated on all physician-review sites.

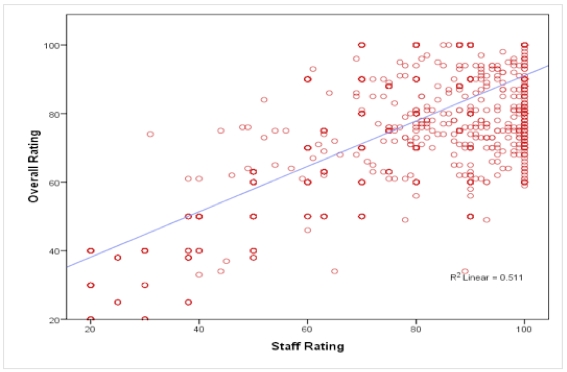

The multiple dimensions of care rated by patients on the physician-rating sites with a 5-point scale had a strong correlation with the overall rating (Pearson correlation, r = .73, P < .001). In fact, the 20 correlations between each of the 5 dimensions of care measured ranged from .715 to .923 (Pearson correlation, P < .001). Even the dimension of care with the lowest correlation coefficient with overall rating (ie, staff rating) was significant: Pearson correlation, r = .715, P < .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation comparing overall rating versus staff rating (n = 4999, Pearson correlation, r = .715, P < .001).

Discussion

Results are Consistent with Prior Studies

This analysis of 4999 physician ratings across 10 websites revealed that approximately 2 out of 3 patient reviews are favorable. These results are consistent with a study that found that 88% of 190 reviews of 81 Boston physicians were favorable [15]. In that study, a positive rating was defined as a rating of 3 or 4 in sites with a 4-point scale, or 4 or 5 in sites with a 5-point scale. Our results are also consistent with a report that showed that 67% of all Yelp reviews in 2008 were 4 or 5 stars [21,22]. The majority of physician-rating websites depend on subjective data input and offer limited quantitative information about quality and cost of care. Despite these limitations, patients like these websites because they provide insight into the patient experience from peers [23,24]. This issue is becoming more important, as some physicians and hospitals are caught off guard by online reviews that are critical of their services [8-11]. The optimal content, structure, and rating methods for online physician-rating sites that are most useful deserve further study [1,25-27].

One Feedback Question May be Sufficient to Assess Patient Experience

In all, 35 different dimensions of care were rated by patients in the websites, with an average of 5 questions per site. There was a high correlation between the overall rating of the physician and the other dimensions of care rated (access, communication skills, facility, and staff). This is consistent with using net promoter score methodology to measure customer satisfaction [28]. This raises the issue of whether 1 question may be sufficient to capture the patient’s general experience. In fact, the more questions on a rating site, the less likely a patient will complete the survey [29-32]. A single question such as “Would you recommend Dr X to a loved one?” may be as useful as the multitude of specific questions currently surveyed [33]. Also, from the physician’s point of view, obtaining actionable information to change communication style, facility, or staff may be better obtained by allowing patients to write in specific feedback and commentary rather than by a scaled survey. In other words, if the facility receives a rating of 1 out of 5 stars, and then the patient comments on how dirty the exam rooms were, then the provider will better understand the low rating.

What makes Physician Ratings Different From Other Professional Service Reviews

Many physicians will take the position that online review sites do not give insight into quality of care. This is valid since obtaining consensus on the definition of quality, even among experts, is challenging. However, patient satisfaction ratings and comments do offer insight into a patient’s experience. As more user-generated content is added, the value of ratings will increase. Patient satisfaction is derived from several factors including the baseline expectation of the patient [25,34,35]. Even government agencies, such as the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the value-based purchasing programs proposal introduced by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), are collecting data on the patient experience [36,37]. CMS even launched a portal of their own to allow for physician comparisons [38]. In fact, the German Medical Association assigned the Agency for Quality in Medicine with the task of elaborating quality standards for online physician- and hospital-rating sites [39]. They suggest that a good online rating site defines how the website is financed, separates rating content from advertising, requires user authentication, provides contact information for the site owner, and allows providers to counter offending statements or correct misinformation.

Despite the overall favorable rating of physicians by patients, the topic of physician ratings is rather sensitive [3,6,10,14,40-47]. Advocates for transparency favor a platform that enables patients to truthfully review their experiences. Yet, with further investigation, a few of these “reviews” have become an outlet for patients who are dissatisfied for not getting what they want despite receiving appropriate medical care. Even worse, some reviews are believed to be acts of sabotage from competing providers or organizations [48-50]. Some physicians have even gone as far as getting a court order to remove a review only to find out that such an action invites Internet vigilantes who find it essential that censorship not be tolerated. Also, patient privacy laws make it very challenging to defend against online misinformation and defamation [48-50]. What makes this issue different from other service industries is that “customers” may die or suffer despite appropriate medical care.

Physician-rating websites hosted by insurance companies have been questioned because of the conflict of interest that insurance companies have by reporting data that can potentially drive patients to providers that are cheap and not because they are good [8]. Consumer review organizations have tried though courts to get access to claims data to report volume of care to the public [51]. However, the American Medical Association and US Department of Health Services and Human won an appeal to protect privacy of physician information. Some physicians request their patients to sign agreements that prohibit them from writing about them on physician-rating websites [49,52,53].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. There is an implicit selection bias to websites that depend on the user to actively engage the review site and write a review. In the future, to get more feedback, providers may bundle review requests with online services such as appointments (eg, ZocDoc.com) and social networking sites. This may reduce the selection bias that limits the value of physician ratings. We derived physician-rating site traffic from Google Trends, which is not an absolute measure of total site traffic. Also, the authenticity of the review may be in question [48-50].

Multimedia Appendix 1

Video of the presentation of Dr Kadry at the Medicine 2.0 Congress at Stanford University, September 18th, 2011 http://www.medicine20congress.com/ocs/index.php/med/med2011/paper/view/539.

Footnotes

None declared

References

- 1.Reimann S, Strech D. The representation of patient experience and satisfaction in physician rating sites. A criteria-based analysis of English- and German-language sites. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:332. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-332. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/10/332.1472-6963-10-332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor H. Harris Interactive. 2010. Aug 4, [2011-10-03]. Press release: "Cyberchondriacs" on the Rise? Those who go online for healthcare information continues to increase http://www.harrisinteractive.com/vault/HI-Harris-Poll-Cyberchondriacs-2010-08-04.pdf.

- 3.Segal J. The role of the Internet in doctor performance rating. Pain Physician. 2009;12(3):659–64. http://www.painphysicianjournal.com/linkout_vw.php?issn=1533-3159&vol=12&page=659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keckley PH. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. 2011. [2011-10-02]. 2011 Survey of Health Care Consumers in the United States: Key Findings, Strategic Implications http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/US_CHS_2011ConsumerSurveyinUS_062111.pdf.

- 5.Fox S, Purcell K. Chronic disease and the Internet. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2010. Mar 24, [2011-10-03]. http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Chronic_Disease.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews M. Grading doctors online. US News World Rep. 2008 Mar 10;144(7):54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Given R. Vitals.comm and MDx Medical, Inc. 2008. Nov 5, [2011-10-03]. MD Rating Websites: Current State of the Space and Future Prospects http://www.vitals.com/res/pdf/health_care_blog_r.givens_11.5.08.pdf.

- 8.Glenn B. The rating game. Patients & insurers are rating the quality of your care. Do you know what they're saying? Med Econ. 2008 Dec 5;85(23):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mostaghimi A, Crotty BH, Landon BE. The availability and nature of physician information on the internet. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Nov;25(11):1152–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1425-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brayer T. Opposing Views, Inc. 2010. Jul 7, [2011-02-22]. Doctor Sues Online Review Sites for Bad Ratings http://www.opposingviews.com/i/doctor-sues-online-review-sites-for-bad-ratings.

- 11.Mills E. CNET News. 2009. Jan 9, [2011-11-09]. Lawsuite Over Yelp Review Settled http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-10139278-93.html.

- 12.Masnick M. Techdirt. 2010. Nov 18, [2011-02-22]. Doctor Sues Patients Over Bad Yelp Reviews http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20101110/19053611809/doctor-sues-patients-over-bad-yelp-reviews.shtml.

- 13.Saxenmeyer Fox Television Stations, Inc. 2010. Nov 16, [2011-02-22]. Chicago Doctor Sues Patients Over Yelp, Citysearch Reviews http://www.myfoxchicago.com/dpp/news/investigative/dr-jay-pensler-yelp-citysearch-reviews-20101115.

- 14.Moyer M. Manipulation of the crowd. Sci Am. 2010 Jul;303(1):26, 28. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0710-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK. Patients' evaluations of health care providers in the era of social networking: an analysis of physician-rating websites. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Sep;25(9):942–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carneiro HA, Mylonakis E. Google trends: a web-based tool for real-time surveillance of disease outbreaks. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Nov 15;49(10):1557–64. doi: 10.1086/630200. http://www.cid.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19845471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seifter A, Schwarzwalder A, Geis K, Aucott J. The utility of "Google Trends" for epidemiological research: Lyme disease as an example. Geospat Health. 2010 May;4(2):135–7. doi: 10.4081/gh.2010.195. http://www.geospatialhealth.unina.it/fulltext.php?f=pdf&ida=89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woyke E. Forbes.com. 2009. Jan 22, [2011-02-22]. America's Most Wired Cities: Seattle Takes the Lead in our Annual List of the Most Broadband-Connected U.S. Cities http://www.forbes.com/2009/01/22/wired-cities-2009-tech-wire-cx_ew_0122wiredcities.html.

- 19.Woyke E. Forbes.com. 2010. Mar 2, [2011-02-22]. America's Most Wired Cities: Raleigh Takes the Lead in Our Annual List of the Most Broadband-Connected U.S. Cities http://www.forbes.com/2010/03/02/broadband-wifi-telecom-technology-cio-network-wiredcities_2.html.

- 20.American Fact Finder US Census Bureau. 2010. Search: Population Estimates for the 25 Largest U.S. Cities http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?ref=geo&refresh=t.

- 21.Stoppelman J. Yelp Web Log. 2009. [2011-10-03]. Yelp vs. YouTube: A Ratings Showdown http://officialblog.yelp.com/2009/09/yelp-vs-youtube-a-ratings-showdown.html.

- 22.Stoppelman J. Bizzy.com. 2011. Apr 4, [2011-10-03]. Yelp Blog Post: Distribution of All Reviews http://blog.bizzy.com/48442434.

- 23.Hay MC, Strathmann C, Lieber E, Wick K, Giesser B. Why patients go online: multiple sclerosis, the internet, and physician-patient communication. Neurologist. 2008 Nov;14(6):374–81. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31817709bb.00127893-200811000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sciamanna CN, Clark MA, Diaz JA, Newton S. Filling the gaps in physician communication. The role of the Internet among primary care patients. Int J Med Inform. 2003 Dec;72(1-3):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2003.10.001.S1386505603001552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bleich SN, Ozaltin E, Murray CK. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ. 2009 Apr;87(4):271–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050401. http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0042-96862009000400012&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.S0042-96862009000400012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrochuk MA. Leading the patient experience. Driving patient satisfaction and hospital selection. Healthc Exec. 2008;23(2):47–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes L, Miles G, Pearson A. Patient subjective experience and satisfaction during the perioperative period in the day surgery setting: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006 Aug;12(4):178–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00575.x.IJN575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinney WC. A simple and valuable approach for measuring customer satisfaction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005 Aug;133(2):169–72. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.060.S0194-5998(05)00384-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beebe TJ, Rey E, Ziegenfuss JY, Jenkins S, Lackore K, Talley NJ, Locke RG. Shortening a survey and using alternative forms of prenotification: impact on response rate and quality. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-50. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/10/50.1471-2288-10-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holbrook AL, Krosnick JA, Pfent A. Lepkowski JM, Tucker C, Brick JM, de Leeuw ED, Japec L, Lavrakas PJ, Link MW, Sangster RL, editors. Advances in Telephone Survey Methodology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. The causes and consequences of response rates in surveys by the news media and government contractor survey research Firms; pp. 499–679. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jepson C, Asch DA, Hershey JC, Ubel PA. In a mailed physician survey, questionnaire length had a threshold effect on response rate. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Jan;58(1):103–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.004.S0895-4356(04)00180-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mailey SK. Increasing your response rate for mail survey data collection. SCI Nurs. 2002;19(2):78–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichheld FF. The one number you need to grow. Harv Bus Rev. 2003 Dec;81(12):46–54, 124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisler T, Svensson O, Tengström A, Elmstedt E. Patient expectation and satisfaction in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002 Jun;17(4):457–62. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.31245.S088354030266053X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalish GH. Satisfaction with outcome as a function of patient expectation: the national antibiotic patient satisfaction surveys. Health Care Innov. 1996;6(5):9–12, 29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality AHRQ. 2011. Oct 26, [2011-11-09]. Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Database https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/CAHPS-Database/About.aspx.

- 37.Anonymous Medicare programs; hospital inpatient value-based purchasing program; proposed rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76(9):2454–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medicare US Department of Health & Human Services. 2011. [2011-02-22]. Physician Compare http://www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1.

- 39.Schaefer C, Schwarz S. [Doctor rating sites: which of them find the best doctors in Germany?] Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2010;104(7):572–7. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2010.09.002.S1865-9217(10)00243-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aungst H. Patients say the darnedest things. You can't stop online ratings, but you can stop fretting about them. Med Econ. 2008 Dec 5;85(23):27–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bacon N. Will doctor rating sites improve standards of care? Yes. BMJ. 2009;338:b1030. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta S. Rating your doctor. Time. 2008 Jan 14;171(2):62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hicks A. Positive patient reviews are possible. Fam Pract Manag. 2009;16(4):10. http://www.aafp.org/link_out?pmid=19626735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hopkins Tanne J. How patients rate doctors. BMJ. 2008;337:a1408. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hungerford DS. Internet access produces misinformed patients: managing the confusion. Orthopedics. 2009 Sep;32(9) doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090728-04.orthopedics.42830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jain S. Googling ourselves--what physicians can learn from online rating sites. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jan 7;362(1):6–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0903473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0903473.362/1/6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pasternak A, Scherger JE. Online reviews of physicians: what are your patients posting about you? Fam Pract Manag. 2009;16(3):9–11. http://www.aafp.org/link_out?pmid=19492765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldberg D. ModernMedicine. 2010. Oct 1, [2011-02-22]. Physicians Have Limited Recourse Against Online Defamation http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/Physicians-have-limited-recourse-against-online-de/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/688470.

- 49.Segal J, Sacopulos MJ, Rivera DJ. Legal remedies for online defamation of physicians. J Leg Med. 2009;30(3):349–88. doi: 10.1080/01947640903146121.913909922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodward C. "Anti-defamation" group seeks to tame the rambunctious world of online doctor reviews. CMAJ. 2009 May 12;180(10):1010. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090679. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19433818.180/10/1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anonymous United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. 2008. May 1, [2011-10-03]. Consumers’ Checkbook v. United States Department of Health and Human Services http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/395/consumers-checkbook-ama-brief.pdf.

- 52.Boodman SG. The Washington Post. 2009. Jul 21, [2011-11-09]. To Quell Criticism, Some Doctors Require Patients to Sign 'Gag Orders' http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2009-03-05-doctor-reviews_N.htm. [PubMed]

- 53.Tanner L. USA Today. 2009. Mar 5, [2011-11-10]. Doctors Seek Gag Orders to Stop Patients' Online Reviews http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2009-03-05-doctor-reviews_N.htm.