Abstract

Secret tobacco industry documents lay bare the industry's targeting, seduction, and recruitment of minority groups and children. They also unmask Big Tobacco's disdain for its targets.

A DECADE AGO, FORMER Winston honcho David Goerlitz sneered that the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company had built its fortune by marketing to “the young, poor, black, and stupid.”1 A tobacco executive who risked such candor today might add, “the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and Hispanic.” But such loose talk is very unlikely today because a series of legal reversals and losses in the court of public opinion have created an acutely circumspect tobacco consortium.

Decades ago, flagrant, disrespectful stereotypes marked the industry's initial courting of African Americans. Sports sponsorships, cartoon characters, and trinkets clearly labeled yesterday's marketing efforts to children and youths. But by the late 1980s, tobacco firms could read the writing on the billboard. Public health advocates and African American activists joined to protest such egregious forms of targeted marketing as the saturation of urban communities with billboards. Even more vociferous protests castigated the design and marketing of cigarettes and tobacco blends targeted exclusively at African Americans.

By the mid-1990s, Minnesota Attorney General Hubert Humphrey III wrested a legal settlement from the nation's major tobacco companies into which he incorporated a brilliant public relations stealth bomb: He forced the release and publication of Big Tobacco's secret internal marketing and research documents on the Internet for all to read. These documents laid bare, in the industry's own damning words, the oft-denied targeting, seduction, and recruitment of minority groups and children. They also unmasked Big Tobacco's disdain for its targets.

The ensuing spate of state and federal legal victories over Big Tobacco has, among other things, specifically banned traditional means of marketing to young people, such as cartoons, billboards, and advertisements in periodicals with significant youth readership.

These developments, while public health successes, have also served to drive tobacco's youth recruitment efforts underground, where they continue, shrouded in coded language and the all-too-familiar denials. The tobacco industry still boasts a marketing budget of $8.4 billion per year for the United States alone,2 and the hidden truth about today's targeted marketing of vulnerable groups such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youths will be even harder to excavate than was yesterday's.

Big Tobacco's past approaches toward targeting minorities, especially African Americans, are illuminating and may prove instructive for detecting its current ploys toward forbidden markets such as youths, especially LGBT youths. For example, Big Tobacco made loyal customers (and defenders) of many African Americans by lavishing positive attention on them when the rest of corporate America still considered Blacks to be marketing pariahs. Tobacco firms hired African Americans before other elements of corporate America welcomed or even accepted them, and tobacco firms infused languishing African American media, cultural, and advocacy groups with desperately needed financial support (box on 1091).

But as the targeted-marketing backlash in the African American community has limited and sometimes stymied tobacco firms' influence, these companies have sought out lucrative new markets. Internal marketing memos show that the tobacco industry has scoured the globe for new target communities as starved for corporate attention and acceptance today as African Americans were yesterday. These new targets include Hispanics, the fastest growing element of the population, and sexual minorities.

Today, tobacco firms are emerging from their corporate closets to openly engage in every type of marketing targeted at gay adults. Most alarmingly, the targeted marketing focuses on LGBT youths, but the cynical marketing snares for the young are carefully hidden and slyly labeled. Today, tobacco's corporate language is sanitized in a Newspeak of acronyms and is bowdlerized to delete any overt reference to youth marketing. The industry whose internal memos once blithely spoke of recruiting Black 14-year-olds is now careful to refer in print and in public only to “young smokers 18 and older.”

SLAUGHTER OF THE INNOCENTS

The tobacco industry has never admitted targeting LGBT youths or even targeting youths at all, despite Joe Camel, cartoons, logo-rich children's trinkets, and sponsorship of youth-oriented sporting and music events. In the face of denials and the recent absence of loose-lipped memos, how can one know that Big Tobacco markets to LGBT youths?

The first clue is a look at the fruits of that targeting, because the overwhelming majority of adult smokers were once underage smokers, and almost no smokers, gay or straight, take up the habit after age 20. Tobacco companies know that they must hook a smoker as a child or not at all, and the US tobacco industry invests $23 million every day to ensure that they do.6–8 Twenty-eight percent of high school students smoke, as opposed to 23% of adults. Every day, 5000 children take their first puff; 2000 are unable to stop and thus swell the ranks of the nation's smokers. One third of the addicted will die from their smoking habits—and this doesn't count the 14% of boys who become addicted to the smokeless tobacco popularized by generations of sports heroes who chew, dip, and spit very publicly.2

A number of studies have determined that children are 3 times as susceptible to tobacco advertising than adults and that such advertising is a more powerful inducement than is peer pressure.9,10

Figure.

Gay and lesbian adults smoke twice as much as their peers.

Ugly as this picture is, the prospects of avoiding tobacco addiction are much bleaker for LGBT youths. The prevalence of smoking is around 46% for gay men and 48% for adult lesbians,11,12 twice as high as for their peers. Data on bisexual and transsexual smoking behavior are sparse, as are data on the smoking behavior of sexual minorities who are also members of high-risk racial and ethnic minority groups. Still, smoking prevalence is likely to be disastrous at the intersection of such high-risk groups.

The smoking rates of LGBT youths are just as high as those of adults, which is hardly surprising. And not only do twice as many LGBTs as other Americans take up smoking; they find it harder to quit, although most want to. Eighty percent of the 1011 adult respondents in a 2001 American Medical Association (AMA)–Robert Wood Johnson (RWJ) Foundation poll said they had tried to stop smoking but could not.13 Like African Americans, members of sexual minority groups pay a much higher medical price for their tobacco addiction. The direct health effects of smoking for gays and lesbians are legion, although the exact figures are still a matter of debate.11 Lesbians who use tobacco face risks of breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and other cancers 5 times higher than those of other women.11 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calculates that the life expectancy of a homosexual man is 8 to 20 years less than that of other men14 and that high smoking rates contribute directly and indirectly to their early deaths. Some researchers fear that cigarette smoking may increase the risk of HIV infection and accelerate the progression to AIDS.15 HIV-positive men have the highest smoking rates of all,15 and heavy smoking triggers immune function changes that also worsen the prognosis for other infectious diseases such as sexually transmitted diseases and hepatitis C.15,16

Figure.

Linking cigarettes, alcohol, and the bar scene has been a staple of tobacco marketing strategies.

Despite all these studies, surveys reveal that gay smokers do not believe that smoking a pack a day constitutes a health risk.17 This is a dangerous attitude, because the health effects of smoking are not always related to the dose.

The scourge of tobacco addiction doesn't wait for adulthood to erode the mental and physical health of LGBT youths. These youths already face much higher vulnerabilities to violence, suicide, and risk-taking behavior (including risky sexual behaviors) than their peers. Young gay smokers are the greatest risk takers; their higher rates of alcohol and drug use15 lead many experts to characterize tobacco as a “gateway drug” for gay youths.

LGBT youths also pay a high price in direct health effects of their smoking addiction, such as 30% to 87% higher rates of cancer. The synergistic effect of tobacco and alcohol encourages a constellation of other respiratory diseases and of ear, nose, and throat diseases; early smoking also inflates the lifetime risks not only of premature death but also of impairments such as blindness and infertility.

Ninety percent of smokers start in their teens,17 and LGBT smokers start even younger; in one survey, 13 years was the median age for girls.18 Tobacco firms therefore know that their efforts to target gays and lesbians will work only if they target gay youths younger than 18, the legal smoking age in most states.

The tobacco industry's targeting of the LGBT communities is a matter of record. Alcohol companies, many owned by tobacco firms, have targeted gays12 as far back as the 1950s, when Joseph Cotton, with a hand resting on his double, slyly touted Smirnoff vodka, “mixed or straight.”19 Tobacco companies have always been aware of sexual minorities as customers who smoked at extremely high rates, but only in the last decade have they embraced marketing targeted at gays in earnest and in large numbers.

The secret tobacco documents placed on various Web sites afford revealing insights into the industry's changing perception of the LGBT communities. Internal memos reveal that tobacco companies sought gay voters' support as early as 1983,2 when they wished to repeal workplace smoking bans in San Francisco.12 An internal Philip Morris memo from 1985 reveals grudging admiration at how views of gays and lesbians as customers were changing: “It seems to me that homosexuals have made enormous progress in changing their image in this country. . . . A few years back they were considered damaging, bad and immoral, but today they have become acceptable members of society. . . .We should research this material and perhaps learn from it.”20

A few years later, when African Americans were successfully protesting targeted community saturation by tobacco firms, the tobacco industry began openly contemplating sexual minorities as a less troublesome market. In the 1990s, just after the protests that aborted the marketing of Uptown to urban African Americans, a “Top Secret Operation Rainmaker” memo listed gays as a marketing “issue” to be discussed.21 Paradoxically, this marketing attention was catalyzed by a concerted political attack mounted on the tobacco consortium by gays. When the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) organized a 1990 boycott of Philip Morris over its support of Jesse Helms, tobacco companies responded by donating large funds to AIDS organizations in appeasement efforts,12 just as they have showered politically pivotal African American organizations with money. Tobacco firms swiftly followed these overtures to gays and lesbians with national advertising campaigns. In 1991, a Wall Street Journal headline trumpeted, “Overcoming a deep-rooted reluctance, more firms advertise to [the] gay community.” The story called gays and lesbians “a dream market” and focused on the tobacco industry's courtship of LGBT media giants such as Genre.22

Between 1990 and 1992, a series of ads for American Brands' Montclair featured an aging, nattily dressed man sporting an ascot, a pinky ring in lieu of a wedding ring, a captain's hat, and an orgiastic expression. This was perceived as a gay or effeminate persona by many readers and media analysts, a reading that American Brands denies. Benson & Hedges, for its part, touted a series of gay-themed ads for its Kings brand in Genre, a gay fashion and lifestyle magazine, as well as in Esquire and GQ, which have significant gay male readerships.

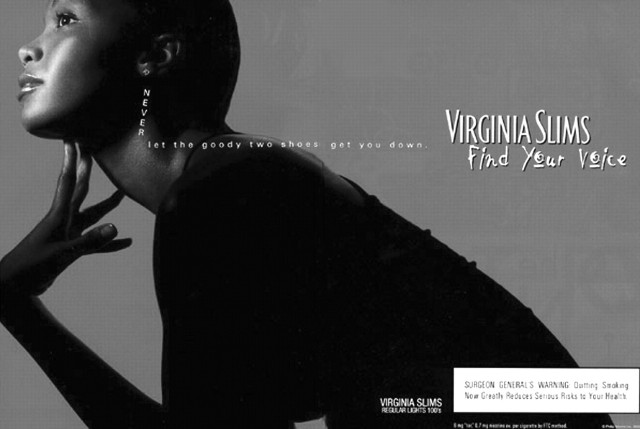

Recent marketers have not overlooked lesbian and bisexual women.12 Philip Morris's Virginia Slims ads send messages of independence, camaraderie, and iconoclasm that appeal to feminists as well as lesbians. But the ads, appearing in such magazines as Essence and Ms., have departed from women in lipstick and heels to feature more androgynous and sexually ambiguous portrayals of women. Women couples are shown fishing in plaid shirts, mesh vests, and hip boots; women duos in tailored clothes are captured in a tête-à-tête over coffee; women even throw appreciative glances at each other on the street over text that exhorts them not to “follow the straight and narrow.”

Marlboro, the most popular cigarette brand among gay men, has flaunted the brand's rugged hypermasculine image in venues calculated to appeal to gays. For example, one large billboard features a close-up of a substantial male crotch clad in weathered jeans with a carton of Marlboros slung in front of it. The image hangs between 2 gay bars in San Francisco's Mission district.12

The health advocacy backlash to Big Tobacco's first flirtation with gay media was swift and sure. The Coalition of Lavender Americans on Smoking and Health (CLASH) issued a press release that read in part, “This is a community already ravaged by addiction: we don't need the Marlboro man to help pull the trigger.”12

BEYOND BILLBOARDS

If the experiences of racial minorities—notably African Americans—serve as a guide, targeted advertising will be just the tip of the tobacco iceberg. The underwriting of key cultural institutions is another insidious route to the control of minority lungs. So is control over the specialized news media that minorities trust. Until 5 or 6 years ago, nearly all African American publishers retained, and sometimes defended, alcohol and tobacco advertisers. For example, in 1998, Dorothy Leavell, who was then president of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, said, “Adult African Americans are mature enough to make [their] own decisions unless government makes tobacco illegal.” Leavell acknowledged that tobacco money provided key support for the 121 publications her group represented: “The tobacco-settlement negotiations have hurt our publications dollarwise.” She lamented the fact that tobacco advertising revenues fell “from a peak of 12–20 million a year [in 1995] to less than 6 million [in 1998]” (D. Leavell, oral communication, 1998).

Many African American publications still embrace and defend tobacco advertising, not from choice, but out of desperation. Alcohol and tobacco corporations have long showered African American publications with advertising and philanthropic revenue while other national corporate advertisers shunned their pages, taking African American consumers' money but refusing to advertise in such important publications as Ebony, Essence, or Jet. Smaller magazines and newspapers found corporate support even more elusive and were often completely dependent upon the tobacco industry (which owns many alcohol companies). Curious news policies ensued; medical writers, for example, were ordered to avoid the topic of smoking, and articles about cardiovascular disease were published that did not mention tobacco use as a risk factor.

Key African American advocacy organizations such as the Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were gratified not only by large bequests but the presence of highly placed, highly visible African American tobacco company staff. For African Americans, tobacco has been a good corporate friend in a hostile corporate universe. In 1992, “R. J. Reynolds also decided “to improve [the employment] recruitment process by the development of an attractive corporate image to be systematically utilized in recruitment ads. . . . [F]eel-good ‘social-responsibility’ campaigns by tobacco companies help the industry not only to sway political and public opinion but to continue to recruit effective salespeople and boost employee morale.” This thrust includes hiring more sexual minorities, supporting their organizations, and addressing issues of importance to LGBT communities.23 In this context, consider the insights of Janelle Lavelle, whose gay advocacy group opposed Senator Jesse Helms's 1990 reelection. At that time, Lavelle told The Advocate, “The protests make working with other minority groups . . . harder because Philip Morris is one of the most labor-positive and minority-positive corporations in North Carolina.” She added, “Philip Morris has openly gay people working at several places. As North Carolina companies go, Philip Morris is a jewel.”24

Today, the targeting of gays and lesbians is escalating because gays constitute a very attractive consumer market. They boast a high disposable income and are “attention-starved and very loyal,” according to Jeff Vitale, president of Overlooked Opinions, an LGBT marketing firm.12 For example, 94% of gay readers in one survey said that they would support advertisers in gay magazines and contributors to gay organizations.12

Figure.

Blacks and other racial/ethnic groups have been targeted by the tobacco industry through ads such as this Virginia Slims ad, with its suggestive undertones.

And, of course, LGBTs have high smoking rates.

LGBT YOUTHS IN THE CROSSHAIRS

This supremely attractive LGBT market has an important feature in common with both heterosexuals and with the racial minorities on which Big Tobacco cut its targeted-marketing teeth: It can be captured and retained only by attracting potential smokers while they are very young.

A 1981 secret Lorillard memo asks rhetorically, “Where should our marketing thrust be?” and replies, “keep riding with Newport” because it is “heavily supported by Blacks and under-18 smokers. We are on somewhat thin ice should either of these two groups decide to shift their smoking habits.”15

Unfortunately, federal and state lawsuits have not ended the seduction of children by Big Tobacco. By 1998, a flurry of successful state and federal lawsuits had snatched from the industry's bag of marketing tricks such options as advertising at sporting events and on billboards and in children's publications. However, Big Tobacco quickly replaced such traditional sponsorships with increased product placement in films, logo-rich announcements, sponsorship of alternative music clubs, and moving billboards on taxis. Such venues are more likely to reach and to appeal to some LGBT youths than traditional sporting events and ads in heterosexual women's and men's magazines. A 2002 University of Chicago report documents that despite the explicit 1998 prohibitions, the 3 largest US tobacco companies have selectively increased youth targeting.26 “Cigarette companies had to become slightly more subtle about it, but they continue to aim their advertising at people under 18,” avers Paul Chung, MD.26

Another reason for the tobacco industry's subtlety in targeting LGBT youths may be that it found young teens responded negatively to overtly sexual messages, according to secret documents generated as early as 1978. A trial advertising campaign for Old Gold filters found that sexually referential advertising “produces no increase in brand switching or awareness and that it does not contribute to the success of Old Gold lights.” The report cited children's negative reactions to “the whole sexual erection thing . . . ‘get it on’ . . . ugh . . . I wouldn't go for it. . . .”27

Sold Down Tobacco Road

WHAT WERE AFRICAN AMERICANs' favorite radio stations in 1967—alphabetized, by city? How many owned automobiles, and where were these car owners most likely to live? What was the African American median income in 1971? How many hours of television did the average Black man watch that year? Did he prefer flavored, filtered, or menthol cigarettes? And exactly how cool a menthol cigarette did he like to smoke–to the degree?

Ask a tobacco company.

The marketing and biochemical research documents that were released as part of Minnesota's 1996 settlement with Big Tobacco reveal a staggeringly exhaustive research dossier on African American culture, habits, physiology, and biochemistry. This intimate portrait of Black America enabled the design of special tobacco products developed with African Americans in mind. The special blends were then painstakingly test marketed down to the smallest cynical details; these included packaging with an Afrocentric red, black, and green color scheme, an “X” logo that evokes political hero Malcolm X, and packs that opened from the bottom because demographic surveys revealed that this was a favored practice of Black men.

The evolution of marketing targeted at African Americans is too complex to describe in great detail here, but its history reveals some important parallels to the way in which Big Tobacco is making overtures to the LGBT communities.

Secret tobacco company documents available on the Internet reveal how the industry meticulously researched African American habits and manipulated corporate and media leadership. The early efforts of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s were crudely stereotypical. Newspapers were to be eschewed in favor of musical advertisements, because “The beat, the tempo, and the ‘feeling’ of the ‘Soul’ music is almost instinctively identifiable to the Negro ear, which is accustomed to this sound.” 3

“... ‘Outdoors’ (hunting, skiing, sailing) is not felt to be suitable, as these are considered unfamiliar to the Negro...”3 The Montclair ads of the 1990s and the Project Scum campaign (see text) mirror such offensive stereotypes.

However, later documents revealed an appalling sophistication both in content and in quality as the targeted marketing became subtler. With the aid of hundreds of surveys, focus groups, and social and even biochemical studies of African Americans, tobacco companies researched and planned very effective marketing campaigns. They even launched special brands, mostly menthol, specifically targeted to African Americans, just as Marlboros, Virginia Slims, and Camels are marketed specifically to LGBT youths today, through marketing campaigns such as Project Scum.

African American communities have been saturated with billboards and placards featuring ethnically diverse smokers, frequent cigarette giveaways, and nefarious tobacco products such as “blunt wraps”—rolls of tobacco used to hold marijuana. For a quarter, children and the poor can buy “loosies,” or illegal single cigarettes, much more frequently in communities of color than in other areas.

But Big Tobacco's siege of the African American community didn't stop there. It proceeded to kill with corporate kindness. In the 1950s, boardrooms and marketing plans tended toward the male and monochromatic. But the top 5 American tobacco companies had discovered that there was green in Black communities, and the tobacco industry offered African Americans influential work and well-paid careers when other companies barred Blacks from their boardrooms.

Just as tobacco companies today hire openly gay staff and pour funds into LGBT organizations, both local and national, they filled the cash-starved coffers of nearly every influential African American organization from the National Urban League to local churches. Tobacco has been the best corporate friend that Black America ever had, pouring so much money into political, social, artistic, and religious organizations that, like hooked smokers, these pivotal African American organizations cannot function without tobacco. Tobacco companies did not forget to invest in important politicians and to shower advertising and other financial support on influential African American news and entertainment media, which have become dependent on this habitual largess.

Today, the 28% smoking rate among African Americans is higher than the national norm. After dropping briefly during the antitargeting backlash of the 1990s,4 smoking rates among African American youths are climbing again. What's worse, 75% of male African American smokers use menthol cigarettes. This is no coincidence, suggests Philadelphia lawyer William Adams, who has brought targeted marketing cases against Big Tobacco.5 He recalls that “In 1957, only 5% of African Americans who smoked consumed menthol products. This represents fantastic growth. The taste for menthol was carefully cultivated by the tobacco industry itself” (W. Adams; oral communications; February 20, 1998, and May 14, 1999).

The 1990s saw a burgeoning African American opposition to targeted marketing, especially to cynically specialized cigarette brands such as Uptown, Camel Menthol, and X, and to the billboards and ads that target minority children. Such opposition has made African Americans increasingly difficult and expensive consumers. The first Surgeon General's Report to focus on the smoking habits of racial and ethnic groups further damaged the relationship between Big Tobacco and African Americans by documenting the persistent targeting of young African Americans.

But the African American community remains vitally important to the cigarette industry. African Americans represent nearly 14% of the population and 38% of its smokers (vs 31% for the total population). African Americans still constitute a large total market share of 8 top brands, especially Kool (20.5%).4

The news media made much of the high recognition of Joe Camel among young children and the plans to use sweet flavorings in cigarettes. More apropos to LGBT youths, however, are marketing strategies directed at youths who are beginning to recognize their sexual identities. For example, in one internal memo, tobacco companies muse how helpful it would be if they could discover that tobacco helps a common health concern such as acne.28

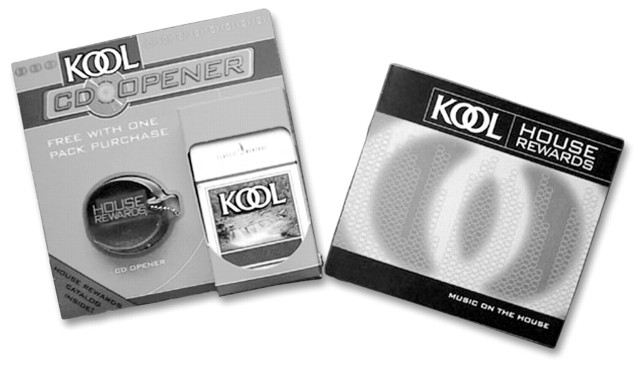

Figure.

Cigarettes are sometimes packaged with free gifts that appeal to both young adults and youths.

Access to cigarettes also remains easy for children. Although cheap “loosies” are more available in minority neighborhoods to African American children, children of all ethnicities can easily buy tobacco products from vending machines and the Internet. A 1983 study showed that 25% of children younger than 13 purchased cigarettes from vending machines.29

Big Tobacco's canon of Newspeak includes an important veiled reference to young smokers: FUBYAS, the acronym for First Usual Brand Younger Adult Smokers. The first brand smoked by a youth is tremendously important to marketers. Smokers are notoriously brand loyal, making it expensive and difficult to induce them to change brands. Therefore, tobacco companies seek to induce seduction by and loyalty to a brand, not to the smoking habit. The tobacco documents reveal a great deal of finely detailed research to tailor tobacco brands to very specific populations and their subgroups. “FUBYAS” are youths because youths constitute the vast majority of “first” smokers. Thus, targeting FUBYAS is, by definition, marketing to youths. For gay markets, this is marketing targeted at gay youths. We know this because tobacco companies do not target children in broad strokes but rather narrowly, by race, by income, and by personality, as illustrated by tobacco documents full of stereotyped descriptions. “The elements that FUBYAS know are their social groups. These are large, loosely knit but highly labeled sub-societies from which FUBYAS draw their identity. . . . The FUBYAS readily classifies others into the groups, and knows what his ‘membership’ is.”30 “This is good news, because therein lies differentiation and opportunity,” concludes a tobacco company document cited in the Washington Post.30

For example, a June 1994 tobacco document observes, “research indicates that adult smokers are of different sexes, races and sexual orientations.”31 The descriptions of these targets are rarely flattering. For example, More brand cigarettes are targeted at women—but not just any women, according to internal marketing memos: “Woman— liberated, but not ball-busting.” Users of generic cigarettes are described as “not mentally stable . . . imageless, hobos, tramps, rag pickers.”32,33

Companies also target children by sexual orientation. As with lesbian Virginia Slims and gay male Montclair campaigns on the early 1990s, the targeting is covert, but it exists. Strategies by which tobacco companies have increased the targeting of LGBT youths include the following:

-

Exploiting the bar culture. In one survey, 32% of lesbians and gays cited the bar culture as a factor in their nicotine addiction.12 Drinking in bars fosters the smoking habit by lowering inhibitions and fuels LGBT alcoholism rates, which are 3 times the national average.12 The synergy of alcohol and smoking is a special hazard for gays, as it multiplies the risks of cancer and other diseases.

The importance of the bar culture is not lost on the industry, whose documents show a heavy marketing investment in bar crowds, including “African American” and “alternative” bars where tobacco company representatives distribute free cigarette samples, hold contests with tobacco premiums as prizes, and sometimes take over the bar to buy free drinks.

Exploiting drug use rates, which are higher among LGBT youths, a fact that Big Tobacco has not hesitated to use to its advantage.

Targeting geographical areas where many young LGBTs congregate socially, such as the Castro and Tenderloin districts of San Francisco.

PROJECT SCUM

The industry that has always denied that it targets youths, despite the detailed statements, reports, and youth marketing plans in its secret internal memos, today refuses to admit its targeting of LGBT youths. Unfortunately, in the absence of a confession, hard evidence is hard to come by. But hard evidence of plans to target LGBT youths can sometimes be excavated from internal tobacco marketing documents that were never meant for consumers' eyes.

Between 1995 and 1997, R. J. Reynolds internal documents recorded corporate-wide overtures to the young LGBT community in what must be one of the least flattering targeted marketing plans in history. In “Project Scum,” R. J. Reynolds tried to market Camel and Red Kamel cigarettes to San Francisco area “consumer subcultures” of “alternative life style.” R. J. Reynolds's special targets were gay people in the Castro district, where, as the company noted, “The opportunity exists for a cigarette manufacturer to dominate.”34 The gay Castro denizens were described as “rebellious, Generation X-ers,” and “street people.” Both the coded labeling of targets as “Generation X-ers” in the mid-1990s and as “rebellious” indicates their youth. Project Scum also planned to exploit the high rates of drug use in the “subculture” target group by saturating “ ‘head shops’ and other nontraditional retail outlets with Camel brand.” More telling than the guardedly worded report itself are the scrawled marginalia such as “Gay/Castro” and “Tenderloin.” The observation “higher incidents [sic] of smoking in subcultures” has the phrase “and drugs” written in.34–36

In one copy, the word “Scum” is crossed out and the word “Sourdough” substituted by a belatedly cautious executive. After such careful sanitizing, the final document could have emerged as Project Sourdough with no clear written evidence that young LGBTs had ever been targeted.

The readiness such documents evinced to exploit the higher drug use rates among LGBT youths sheds marketing light on some dubious promotional devices. For example, Philip Morris has given away key rings with its Alpine Extra Light cigarettes that conceal a screw-top glass vial. Surveys by the smoking cessation group Quit, from Melbourne, Australia, suggest that most youths think these premiums are for holding drugs. Unprompted, 10 of the 13 groups surveyed suggested that the vials were meant to carry “drugs,” “coke,” “stash,” and “speed.” One youth summed it up: “It's a key ring, and it's what people typically use to carry drugs.”37

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS

In the early 1990s, tobacco companies began forging legislative and political ties with the LGBT community, just as they had with many African American politicians, the African American news media, and with groups such as the National Urban League. The tobacco industry began introducing antidiscrimination bills that purported to offer protection against sexual-orientation bias but whose addenda and riders protected the rights of smokers—and of the companies that feed smokers' habits. According to the Tobacco Institute, by September 23, 1992, the industry had enlisted the help of local gay and lesbian alliances to pass smoker protection/“antidiscrimination” laws in 20 states.38

Sometimes, however, tobacco companies knew that anti-tobacco LGBT groups troubled by high rates of LGBT addiction would not support them, so they formulated plans to cut these leadership groups out of the picture and appeal directly to gay voters.

In 1998, California voters were offered Proposition 10, a measure to substantially hike cigarette taxes. A concerned Tobacco Institute (an industry consortium) sought professional advice from marketers, researchers, and consultants on how best to garner the gay vote. Consultant David Mixner advised the Tobacco Institute “to bypass” gay organizations: “Since it is apparent that we are not going to have the endorsement of most Gay and Lesbian leadership, it is important to use these campaign tools to bypass that and go directly to the Gay and Lesbian voter with a message that will resonate.”39

Just as struggling African American media tended to defend (or to conveniently ignore) targeted marketing by Big Tobacco, some LGBT media view tobacco's growing attention to gay and lesbian customers as a boon.

In response to a August 17, 1992, Wall Street Journal story by Joanne Lipman, Don Tuthill, the publisher of Genre, wrote, “The Philip Morris/Genre story is not a story of

‘the tobacco industry . . . turning its marketing muscle on another minority’; it is a story of inclusion . . . a story about a major marketing company recognizing, including and supporting a frequently disenfranchised and overlooked segment of the U.S. population. . . . this is exactly the kind of support that gay media has sought for years.”40

Joe Landry, publisher of Out and The Advocate, crowed that Big Tobacco's advertising “shows we’re making progress. . . . Lots of companies are adding diversity marketing to their budgets, which used to mean money for advertising mainly to blacks and Hispanics, but now it's meant largely, and sometimes mainly, for gay and lesbian customers.”41

However, the targeting of racial and ethnic groups is hardly a thing of the past; indeed, it is escalating and gaining precision. For example, a perusal of the online tobacco documents shows that tobacco companies have added surgically precise research on Hispanic markets to their ethnic marketing mix.

As early as 1988, Philip Morris sought to expand its pursuit of the US Hispanic community by sponsoring soccer events, Latin music events, and Hispanic festivals and by giving away cigarettes. The proposed budget for the Hispanic Marlboro campaign alone was $3.5 million.42–44

Recently, however, such targeting has achieved sophistication; it is no longer in broad strokes but rather surgical strikes. For example, although Lorillard market research details that African American men are the largest market for menthol cigarettes, in some Los Angeles and New York Hispanic communities, menthol is perceived as the choice of gay men. But in others menthol is seen as macho, and in still others as an acceptable choice for anyone, man or woman.42

In sum, one can see dramatic parallels between tobacco's courtship of the LGBT community today and its targeted marketing of African Americans decades ago. The industry gave African Americans the corporate attention and acceptance they craved, advertising in their media and neighborhoods. It became a generous and attentive corporate friend, investing heavily in African American organizations of every stripe. It hired many African Americans and non-White women in positions of responsibility in an era when boardrooms were male and monochromatic.

Behind the scenes, however, Big Tobacco's secret documents reveal that it slyly targeted children and knowingly sabotaged the health of a community already ravaged by high disease rates.

Today, tobacco companies view both racial and sexual minorities as key markets. Targeted marketing of tobacco to sexual minorities seems likely to mirror the process that worked so powerfully to addict and sicken African Americans.

Marketing targeted at LGBTs will probably accelerate, for several reasons:

The LGBT community is an extremely attractive new consumer base, with high disposable income, a very brand-loyal culture, a tradition of tobacco use, and a hunger for corporate attention and acceptance.

The Internet will make it irresistibly quick and easy to precisely target and survey specific demographic groups within the LGBT community for specific tobacco products, much easier than detailing racial minorities has been during the past 40 years.

The Internet also offers a way to market and sell cigarettes to underage youths, including LGBT youths.

All this means that we may see marketing aimed at LGBTs—and, by implication if not definition, at young LGBTs—escalate in scope and directness. The wave of the future may be revealed by Germany's Reemstma tobacco company, whose advertisements have thrown yesterday's coded ambiguity to the winds. Ads for its New West brand have featured a gay male marriage and copy that exhorted, “Men! . . . taste how strong this one is.”12 Reemstma's Web sites include one labeled “Queer,” which offers a dazzling cornucopia of advertisements, news, fashion, music, games, chat rooms, explicit gay pornography, and, of course, tobacco products, all tailored to the tastes and interests of LGBT consumers.45

What better illustration of how Big Tobacco increasingly views the LGBT community with lust rather than apprehension? As a growing number of companies court the gay market, analysts predict that this desirability will achieve widespread corporate acceptability. Then tobacco advertising may become omnipresent within the LGBT communities, just as tobacco billboards, ads, promotions, sponsorship, employees, and products did in African American communities by the 1970s, seducing new generations of smokers.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Tobacco Institute memo from Samuel Chilcote, Jr, to Rep. Thomas Luken's Subcommittee on Transportation and Hazardous Materials [re: Protect Our Children From Cigarettes Act of 1989]. July 26, 1989. Bates No. 515687450. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/rjr/515687449-7757.html. Accessed May 15, 2002.

- 2.The campaign for tobacco-free kids. Available at: http://tobaccofreekids.org/adgallery. Accessed April 21, 2002.

- 3.Holland G. A study of ethnic markets [by R. J. Reynolds marketing officials]. September 1969. Bates No. 501989230. Available at: http://www.tobaccodocuments.org. Accessed June 17, 1998.

- 4.Stolberg SG. Rise in smoking by young blacks erodes a success story. New York Times. April 4, 1998: A24.

- 5.Slobodzian J. Civil rights suit names tobacco. Natl Law J. November 2, 1998:A10.

- 6.DiFranza JR, Librett JJ. State and federal revenues from tobacco consumed by minors. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1106–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The toll of tobacco in the United States of America. Available at: http://tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0072.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2002.

- 8.Cummings KM, Pechacek T, Shopland D. The illegal sale of cigarettes to us minors: estimates by state. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:300–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans N, Farkas A, Gilpin E, Berry C, Pierce JP. Influence of tobacco marketing and exposure to smokers on adolescent susceptibility to smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Berry CC. Tobacco industry promotion of cigarettes and adolescent smoking [with erratum in JAMA. 1998; 280:422]. JAMA. 1998;279:511–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesbians and Smoking Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: NOW Foundation; October 16, 2001. Available at:http://www.nowfoundation.org/health/lybdkit/factsheet.html. Accessed March 4, 2002.

- 12.Goebel K. Lesbians and gays face tobacco targeting. Tob Control. 1994;3: 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Author unknown. Most smokers try to quit, but can't [poll]. September 11, 2001. Available at: http://www.umich.edu/~umtrn/websites.html. Accessed September 11, 2001.

- 14.Bosworth, Brandon. A last drag? Am Enterprise Online. November 15, 2001. Available at: http://www.theamericanenterprise.org/hotflash011115.htm. Accessed May 23, 2002.

- 15.Ardey DR, Edlin BR, Giovino GA, Nelson DE. Smoking, HIV infection and gay men in the United States. Tob Control. 1993;2:156–158. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newell GR, Mansell PW, Wilson MB, Lynch HK, Spitz MR, Hersh EM. Risk factor analysis among men referred for possible acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Prev Med. 1985;14:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paralusz KM. Ashes to ashes: why FDA regulation of tobacco advertising may mark the end of the road for the Marlboro Man. Am J Law Med. Spring 1998;24:89–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosario M, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Exploration of substance abuse among lesbian gay and bisexual youth: prevalence and correlates. J Adolesc Res. October1997;12:454–476. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steele BC. From pickups to SUVS: winking ads that appealed to gay men as early as the 1950's lead the way for today's bold appeals to lesbian and gay consumers. The Advocate. August 15, 2000:14.

- 20.Philip Morris marketing memo, March 29, 1985. Bates No. 2023268366/8374. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed March 1, 2002.

- 21.Top Secret Operation Rainmaker, Tuesday, 20 March 1990. Bates No. 2048302227–2048302230. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/usc_tim/1251.html. Accessed May 20, 2002.

- 22.Rigdon JE. Overcoming a deep-rooted reluctance, more firms advertise to gay community. Wall Street Journal. July 16, 1991: B1.

- 23.Institute for Consumer Responsibility. Georgians Against Smoking Pollution newsletter. 1984 (est.). Bates No. 2045748385-8398. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/usc_tim/2045748385-8398.html. Accessed March 6, 2002.

- 24.Institute for Consumer Responsibility. [No title]. 1984 (est.). Bates No. 2045748385-2045748398. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/pm/2045748385-8398.html. Accessed March 28, 2002.

- 25.Replies to 5-year plan questionnaire. 1981. Bates No. 03490806-03490844. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/youth/AmYoLOR00000000.Rm.html. Accessed May 20, 2002.

- 26.Cigarette ads target youth, violating $250 billion 1998 settlement [press release]. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Hospitals & Health System, Public Relations Office; March 12, 2002.

- 27.OGF Vitality Test WAVE II. Bates No. 91145517-91145643. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/lor/91145517-5643.html. Accessed May 23, 2002.

- 28.Memo suggesting consideration of formation of a scientifically oriented group to review work made at tobacco industry expense. Tobacco Institute. June 19, 1974. Bates No. TIMN0068332. Available at: http://www.smokescreen.org. Accessed March 7, 2002.

- 29.Kessler DA, Witt AM, Barnett PS, et al. The Food and Drug Administration's regulation of tobacco products. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:988–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.[Author unknown.] Cigarette marketers' decades-old stereotypes may threaten today's deal. Washington Post. January 19, 1998: A23.

- 31.Landman A. Confidential—recap of Hispanic meeting. Bates No. 2060286766. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/landman/2060286766.html. Accessed March 8, 2002.

- 32.Bender G. Image attributes of cigarette brands. For Brown and Williamson Tobacco Corp. January 1982. Bates No. 670575136-670575158. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/usc_tim/247684.html. Accessed April 1, 2002.

- 33.Mindset segments. January 3, 1991. Bates No. 510320848– 510320876. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/landman/510320848-0876.html. Accessed April 1, 2002.

- 34.Simkins BJ. Project Scum. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. December 12, 1995. Bates No. 518021121– 518021129. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/landman/518021121.html. Accessed April 4, 2002.

- 35.Project Scum. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. April 2, 1996. Bates No. 519849940–519849948. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/rjr/519849940-9948.html. Accessed April 4, 2002.

- 36.O'Conner LM. Project Scum. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. 1997. Bates No. 517060265–517060272. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/rjr/517060265-517060272.html. Accessed January 28, 2001.

- 37.Chapman S. Campaigners accuse tobacco firm of dubious ploy. BMJ. 2000;320:1427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anti-discrimination measures. The Tobacco Institute. September 23, 1992. Bates No. TIMN0030964-TIMN0030965. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/ti/TIMN0030964-0965.html. Accessed May 20, 2002.

- 39.Mixner D. Memo from DBM Associates [consultant to the Tobacco Institute] to Grant Gillham, Joe Shumate & Associates, Inc. Bates No. TCAL0404793. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/landman/TCAL0404793.html. Accessed April 14, 2002

- 40.Letter to Joanne from Don Tuthill. August 17, 1992. Bates No. 2023439114. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/pm/2023439114-9115.html. Accessed March 1 2002.

- 41.Pertman A. Gay market, ads target big dollars, not big change. Boston Globe. February 4, 2001:E1.

- 42.Marlboro Hispanic promotions 880000 marketing plan. 1988 (est). Bates No. 2048679289/294. Available at: http://www.tobaccodocuments.org/pm/2048679289-9294.html#images. Accessed April 21, 2002.

- 43.Hispanic market opportunity assessment. Progress update presentation. January 1985. Bates No. 504617452– 504617507. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/rjr/504617452-7507.html. Accessed April 21, 2002.

- 44.The Hispanic market. February 10, 1983. Bates No. 2042463401– 2042463437. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/pm/2042463401-3437.html. Accessed March 10, 2002.

- 45.Reemtsma West brand cigarettes “Queer” Web page. Available at: http://www.west.de/queer. Accessed May 15, 2002.