Abstract

American Indians and Alaska Natives continue to experience significant disparities in health status compared with the US general population and now are facing the new challenges of rising rates of chronic diseases. The Indian health system continues to try to meet the federal trust responsibility to provide health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives despite significant shortfalls in funding, resources, and staff. New approaches to these Indian health challenges, including a greater focus on public health, community-based interventions, and tribal management of health programs, provide hope that the health of Indian communities will improve in the near future.

I HAVE EXPERIENCED THE health challenges faced by American Indians and Alaska Natives from a number of perspectives over time. As an American Indian child, I received health care in an Indian Health Service (IHS) facility, and i was aware at an early age that the burden of health problems was significant. Every visit to the clinic meant a 4-hour wait in a crowded waiting room. I heard the complaints of relatives about the poor care they received, and there was always a sense that better care was available in the non-Indian health clinics nearby. I also noticed that I had never seen an American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) doctor in the clinic. Perhaps if there were more AI/AN doctors, I thought, health care would be more culturally appropriate and of higher quality.

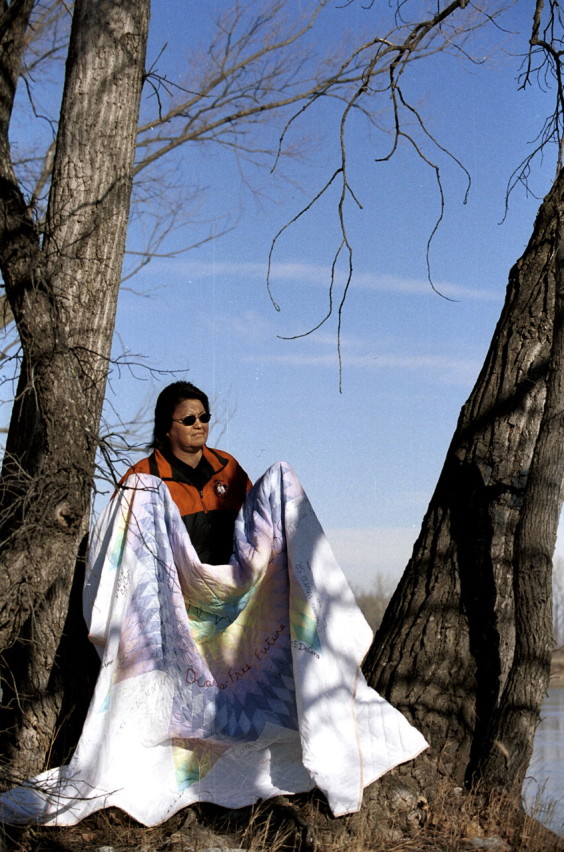

A Winnebago woman holds a memorial quilt with the names of members of her tribe who have died from diabetes complications.

Photo by Mary Anne Pember.

From my perspective years later, as an American Indian physician working in the IHS, I noted that the problems and challenges in Indian health care were still there, and now I was the doctor people waited 4 hours to see. The burden of chronic diseases was so significant that I was often surprised to see a patient without diabetes. The epidemic of diabetes in Indian communities, especially in the Southwest, has become so great that in some AI/AN communities, 40% to 50% of adults have diabetes.1,2 Cardiovascular disease, once thought to occur less commonly in the AI/AN population than in the US general population, is now the leading cause of death for all American Indians and Alaska Natives.3 The growth in the prevalence of chronic diseases in this population is a crisis for the IHS, which was originally designed as a hospital-based, acute care system and is currently severely underfunded.

THE FEDERAL TRUST RESPONSIBILITY

The federal government has a trust responsibility to provide health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives, based on multiple treaties, court decisions, and legislative acts. However, the IHS is critically underfunded. Although its budget for fiscal year 2002 is $2.8 billion, tribal leadership has estimated that a needs-based budget for Indian health care should be closer to $18 billion. Per capita expenditures for Indian health care were approximately one third as much as expenditures for individuals in the US general population in 2001.4 Lack of adequate funding and services is a constant stress on the Indian health system and plays a significant role in the continuing health disparities in Indian communities.

A Winnebago youth tests his blood sugar level while seated at his family’s kitchen table. Both his parents have type 2 diabetes.

Photo by Mary Anne Pember.

From my current perspective as a public health professional, I have learned of the adverse impacts of past policies, such as the Dawes Act of 1887, which served to attempt to acculturate Indian people into the dominant society at the time. This act made it illegal to speak traditional languages or practice traditional customs, and it also divided Indian lands into allotments for each family, which disrupted the social and group structure of the tribes.5 As a result of this policy, the health of American Indians declined rapidly and thousands died. Fortunately, this decline in health status was recognized in the early 1900s, and Congress passed the Snyder Act in 1921 to authorize funding for the “conservation of health” in Indian communities. The Dawes Act is an important reminder of the horrible impact that public health policies can have on the health of a population, but is it any less horrible for the present-day federal government to fund the Indian health system at levels far below the real level of need?

POSITIVE CHANGES IN INDIAN HEALTH

From a public health perspective, I see hope for the health of Indian communities in a number of positive changes occurring in the Indian health system. The number of American Indians and Alaska Natives is growing, according to the US Census Bureau, which counted 4.1 million people who self-identified as AI/AN alone or in combination with other races in 2000 (US Census Bureau, February 2002, http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01=15.pdf). Along with this increase in population comes an increase in the numbers of AI/AN health professionals who are returning to Indian communities to provide health care.

One of the most significant changes in the Indian health system has been the Indian SelfDetermination and Educational Assistance Act of 1975 (PL 93-638; 88 Stat 2203; 42 USC 450-458), which allows tribes to manage the health programs in their community previously managed by the IHS.6 The number of tribes that have opted to manage their health programs has grown rapidly, and approximately half of the IHS budget is now managed by tribes.4 A recent survey showed that tribes that manage their own health programs, on average, were able to provide more new health programs, build more new facilities, and collect more third-party reimbursements than had been the case under IHS management.7 Evidence is growing that tribal management of health programs can be successful and can lead to better ways to address the health problems of American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Another positive change has been the recognition that Indian communities must play a central role in improving their health. As sovereign nations, tribes are now asserting their rights and taking responsibility for their health. Many tribes are establishing wellness programs and fitness centers and are relearning their tribal traditions related to health.8 Tribes are also taking more control over the research that is conducted in their communities and are establishing institutional review boards to ensure that the research benefits their tribes, addresses their own research priorities, and involves the community at all levels of the research—design, conduct, and interpretation of the results.9,10 It is no longer acceptable for researchers and public health workers to enter Indian communities without the approval and participation of the tribe, collect data, and leave.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH RESPONSE

As public health professionals, we have new responsibilities to support these positive changes in Indian health that provide hope and create opportunities to restore the health of Indian communities. We must learn more about the health challenges and disparities in Indian communities and about the specific tribes we serve. In our public health efforts we must insist on the full participation of the tribes and community in all phases of planning, implementation, and evaluation of programs, services, and research. We also must resist the temptation to enter Indian communities as “experts” who will control programs and outcomes. A more productive role is to be a resource to the community and to help build local capacity.

We also must help educate others, especially our country’s leaders, on the severe levels of underfunding and lack of resources in the Indian health system and the need for more funding for Indian health care. The federal government has a responsibility to provide health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives, and it is time for all of us to respect the sovereignty of tribes, help build capacity in Indian communities, and help reduce the health disparities that affect this population.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Lee ET, Howard BV, Savage PJ, et al. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in three American Indian populations aged 45-74 years. The Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Will JC, Strauss KF, Mendlein JM, et al. Diabetes mellitus and Navajo Indians: findings from the Navajo Health and Nutrition Survey. J Nutr. 1997;127(suppl 10):2106S–2113S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trends in Indian Health. Washington, DC: Indian Health Service; 1998–1999.

- 4.Indian Health Service Year 2001 Profile. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; April 2001.

- 5.Shelton BL. Legal and historical basis of Indian health care. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, eds. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001:1–30.

- 6.Dixon M, Mather DT, Shelton BL, Roubideaux Y. Economic and organizational changes in Indian health care systems. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, eds. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001:89–121.

- 7.Dixon M, Shelton BL, Roubideaux Y, Mather D, Smith CM. Tribal Perspectives on Indian Self-Determination and Self-Governance in Health Care Management. Denver, Colo: National Indian Health Board; 1998.

- 8.IHS National Diabetes Program Special Diabetes Program for Indians, Interim Report to Congress. January 2000. Available at: http://www.ihs.gov/MedicalPrograms/Diabetes/creport5-19.pdf (PDF file). Accessed July 5, 2002.

- 9.Roubideaux Y, Dixon M. Health surveillance, research, and information. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, eds. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001:253–274.

- 10.Norton IM, Manson SM. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: navigating the cultural universe of values and process. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]