Abstract

Bacteria are surrounded by a cell wall containing layers of peptidoglycan, the integrity of which is essential for bacterial survival. In the final stage of peptidoglycan biosynthesis, peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases (PGTs; also known as transglycosylases) catalyze the polymerization of Lipid II to form linear glycan chains. PGTs have tremendous potential as antibiotic targets, but the potential has not yet been realized. Mechanistic studies have been hampered by a lack of substrates to monitor enzymatic activity. We report here the total synthesis of heptaprenyl-Lipid IV and its use to study two different PGTs from E. coli. We show that one PGT can couple Lipid IV to itself whereas the other can only couple Lipid IV to Lipid II. These in vitro differences in enzymatic activity may reflect differences in the biological functions of the two major glycosyltransferases in E coli.

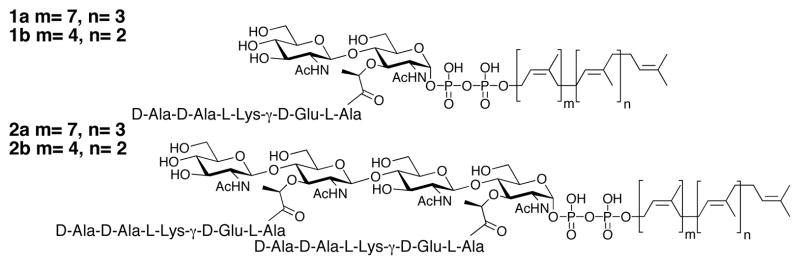

Peptidoglycan (PG) is a crosslinked carbohydrate polymer that surrounds and protects bacterial cell membranes, enabling bacteria to withstand large fluctuations in internal osmotic pressure. Because peptidoglycan is essential for bacterial cell survival, the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of PG are targets for antibiotics.1 Over the past fifteen years, great progress has been made toward understanding the different steps of PG synthesis,1 but there is still one family of enzymes that remains poorly characterized: the peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases (PGTs) that catalyze formation of the carbohydrate chains of peptidoglycan from a disaccharide precursor called Lipid II (1, Figure 1).2 Bacteria typically contain several different PGTs whose biological roles are poorly understood. Biochemical studies of PGTs have been hampered by difficulties in obtaining substrates to dissect the polymerization mechanism. The first coupling catalyzed by PGTs involves the condensation of two Lipid II substrates to form a tetrasaccharide, Lipid IV (2, Figure 1). Subsequent coupling cycles involve the elongation of the growing polymer by addition of Lipid II subunits. Therefore, after the first coupling cycle, the substrates used by PGTs are different. In order to probe the mechanism of glycosyltransfer and to characterize enzyme inhibitors, it is essential to have Lipid II substrates (1) as well as a longer substrate representing the growing polymer (such as Lipid IV, 2). We and others have previously developed approaches to obtain Lipid II,3 but longer substrates have not been reported.4 Here we describe the total synthesis of heptaprenyl-Lipid IV (2b) and we show that both major E. coli PGTs, PBP1a and PBP1b, couple this substrate to heptaprenyl-Lipid II (1b).5 Unexpectedly, PBP1a also couples Lipid IV subunits to one another, suggesting that some PGTs may be able to ligate longer glycan polymers in addition to building glycan chains from Lipid II.

Figure 1.

undecaprenyl-Lipid II (1a) and Lipid IV (2a); heptaprenyl-Lipid II (1b) and Lipid IV (2b).

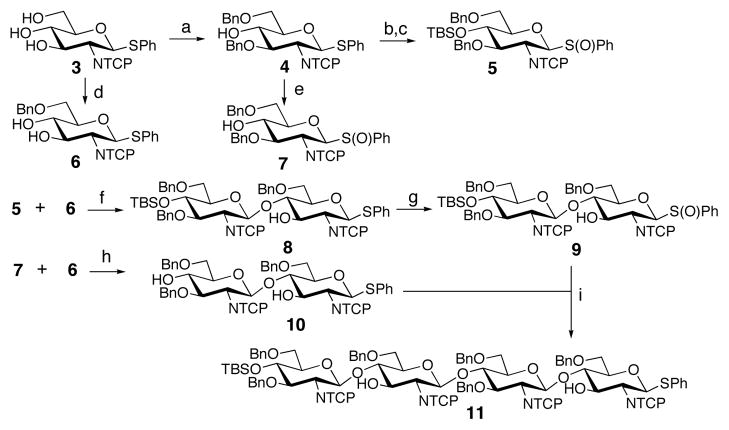

Our route to Lipid II involves the chemical synthesis of Lipid I followed by the enzymatic construction of the β-1,4-glycosidic linkage using E. coli MurG.3(a),6 While this chemoenzymatic approach using a purified enzyme as the final step is efficient, enzymes to make longer glycan polymers with control over product length are not yet available. Therefore, all the glycosidic linkages in Lipid IV must be constructed chemically prior to installation of the sensitive diphospholipid moiety at the reducing end of the molecule. β-1,4 glycosidic linkages between 2-amino-2-deoxy sugars occur frequently in nature, but remain challenging to synthesize, in part because of the low reactivity of the C4 hydroxyl. We chose tetrasaccharide 11 (Scheme 1) as a key intermediate and established the goal of constructing all the glycosidic linkages using the sulfoxide glycosylation method. The monomer building blocks 5, 6 and 7 were readily synthesized in multi-gram quantities from a common intermediate 3 (Scheme 1). 5 and 6 were coupled to obtain the desired β-1,4-linked disaccharide 8 in 75% yield. The bulky tetrachlorophthalimido (TCP) group hindered reaction of the unprotected C3 hydroxyl of 6, while favoring the β-anomeric product, enabling regio- and stereo-selective glycosylation.7 Disaccharide 10 was produced in 58% yield by inverse addition of the partially protected glycosyl donor 7 to the acceptor 6.8 Reaction of the C4 hydroxyl of 6 with activated donor 7 was favored over self-condensation of 7, which also contains an unprotected C4 hydroxyl.9 In the next step, however, this unprotected C4 hydroxyl reacted preferentially over the C3 hydroxyls of 9 and 10 to produce tetrasaccharide 11. Thus, the use of partially protected glycosyl donors and acceptors at several different steps enabled a convergent tetrasaccharide synthesis with a minimum of protecting group manipulations.

Scheme 1.

Construction of Lipid IV tetrasaccharide backbonea

a Conditions: (a) Bu2SnO, toluene, reflux, then Bu4NI, BnBr, reflux, 51%; (b) TBSOTf, 2,6-lutidine, CH2Cl2, 91%; (c) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, −78 to −60 °C, 93%; (d) i. (Bu3Sn)2O, MeOH, reflux; ii. Bu4NI, BnBr, toluene, 91 °C, 75%; (e) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, −78 to −60 °C, 91%; (f) ) Tf2O, DTBMP, ADMB, MS 4Å, CH2Cl2, −60 to −30 °C, 75%; (g) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, −78 to −60 °C, 86%; (h) Tf2O, DTBMP, ADMB, MS 4Å, CH2Cl2, −60 to −40 °C, 58%; (i) Tf2O, DTBMP, ADMB, MS 4Å, CH2Cl2, −40 °C, 77%.

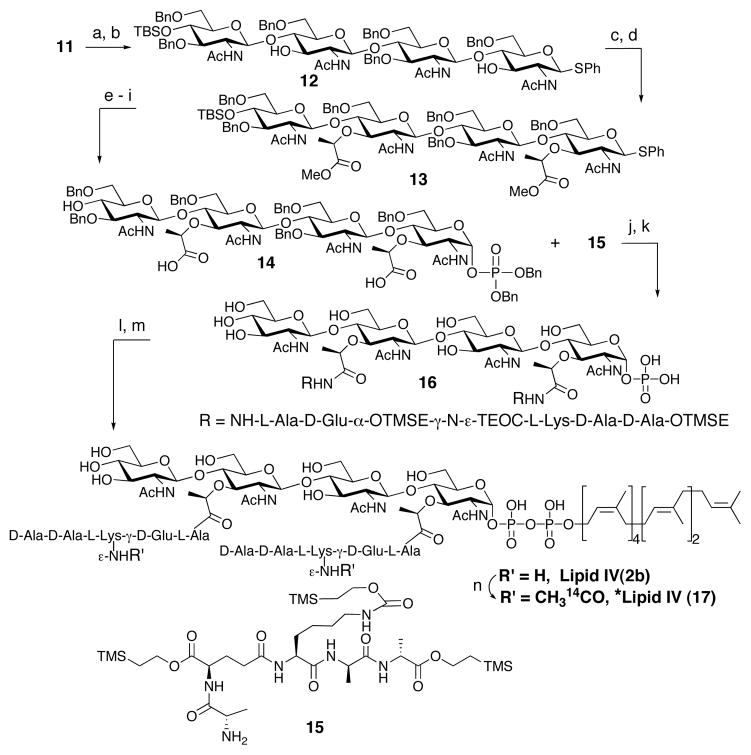

The N-TCP amides of 11 were converted to the N-acetyl amides as shown, and the two D-lactate and 1-alpha-phosphate moieties were then installed to afford the desired intermediate 14 in 9 steps with a 21% overall yield (Scheme 2). The silyl protected pentapeptide 15 was synthesized using Fmoc chemistry and coupled to 14 using standard peptide coupling conditions. Global hydrogenolysis provided 16. Heptaprenyl phosphate, synthesized as described,3(a) was coupled to the anomeric phosphate 16 using CDI. The addition of SnCl2 as a Lewis acid accelerated the coupling reaction and improved the yield significantly.10 Finally, global deprotection of the silyl groups led to the desired target, heptaprenyl-Lipid IV (2b). This compound was treated with 14C-acetic anhydride to make *Lipid IV (17) in order to assay enzymatic activity.

Scheme 2.

Completion of the synthesisa

a Conditions: (a) (NH2CH2)2, THF/CH3CN/EtOH (1:2:1), 60°C; (b) Ac2O, MeOH/H2O (5:1), rt, 75% two steps; (c) NaH, S-(−)-2-bromo-propionic acid, THF, 0 °C to rt; (d) TMSCHN2, benzene/MeOH (3:1), 0 °C, 70% two steps; (e) NIS, CH3CN/H2O (5:1), rt, 75%; (f) 1H-tetrazole, (i-Pr)2NP(OBn)2, CH2Cl2, −40 to −20 °C; (g) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, −40 °C to rt, 84% two steps; (h) TBAF, THF, 0°C to rt; (i) 1.3 M KOH, THF/H2O (10:1), rt, 64% two steps; (j) HATU, DIEA, DMF, rt, 60%; (k) Pd(OH)2/C, H2, 44%; (l) ammonium heptaprenyl phosphate, 1,1′-carbonyl diimidazole, THF, rt, then 16, SnCl2, DMF, rt, 50%; (m) TBAF, DMF, rt, 69%; (n) (CH314CO)2O, toluene/16 mM NaOH in MeOH (1:1), sonication, 37°C, 50%.

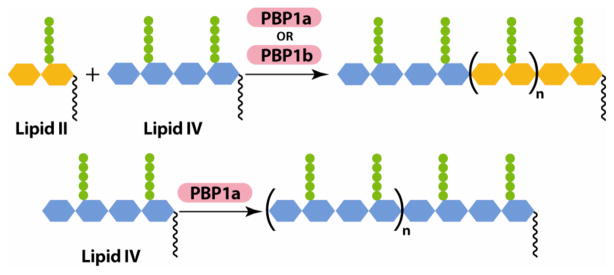

*Lipid IV was incubated with either E. coli PBP1a or PBP1b (Table 1), and reactions were analyzed as described previously.11 PBP1b did not utilize Lipid IV as a substrate unless Lipid II was also included in the reaction mixture (Table 1).12 This result is consistent with the accepted mechanism for transglycosylation, in which Lipid II subunits are added sequentially to a growing polymer chain (Scheme 3, top). Surprisingly, however, PBP1a was able to convert Lipid IV to peptidoglycan polymer in the absence of Lipid II (Scheme 3, bottom), showing that Lipid II is not an obligatory substrate for all PGTs. This result suggests that the biological functions of some PGTs may include coupling peptidoglycan oligomers. The work reported here demonstrates the utility of Lipid II and Lipid IV substrates to probe the mechanisms of PGTs, and more detailed studies are underway.

Table 1.

Percentage of peptidoglyan formed from 14C-Lipid IV (17)a

| enzyme (nM) | time (min) | 12C 1 (μM) | 14C 17 (μM) | % conversion to peptidoglycanb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 84 (PBP1b) | 90 | 0 | 0.4 | undetectable |

| 84 (PBP1b) | 360 | 0 | 0.4 | undetectable |

| 84 (PBP1b) | 10 | 4 | 0.32 | 40.8 |

| 86 (PBP1a) | 90 | 0 | 0.4 | 27.9 |

| 86 (PBP1a) | 360 | 0 | 0.4 | 46.0 |

| 86 (PBP1a) | 10 | 4 | 0.32 | 51.1 |

All the experiments were carried out in the presence of penicillin G to prevent peptide crosslinking. For experimental procedures, see supporting information.

Conversion is based on utilization of 14C-labeled 17.

Scheme 3.

Reactions catalyzed by PBP1b (top) and PBP1a (top and bottom)a

aLipid II is proposed to add to the reducing end of the growing glycan chain, as shown in the top depiction.13

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH (GM076710).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral data for all compounds. Enzyme expression, purification, and reaction conditions. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Walsh C. Antibiotics: actions, origins and resistance. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2003. pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostash B, Walker S. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ye XY, Lo MC, Brunner L, Walker D, Kahne D, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3155–3156. doi: 10.1021/ja010028q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schwartz B, Markwalder JA, Wang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11638–11643. doi: 10.1021/ja0166848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) VanNieuwenhze MS, Mauldin SC, Zia-Ebrahimi M, Winger BE, Hornback WJ, Saha SL, Aikins JA, Blaszczak LC. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3656–3660. doi: 10.1021/ja017386d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Breukink E, van Heusden HE, Vollmerhaus PJ, Swiezewska E, Brunner L, Walker S, Heck AJR, de Kruijff B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19898–19903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peptidoglycan fragments lacking the diphospholipid moiety have been prepared. See Hesek D, Lee MJ, Morio KI, Mobashery S. J Org Chem. 2004;69:2137–2146. doi: 10.1021/jo035583k.Inamura S, Fujimoto Y, Kawasaki A, Shiokawa Z, Woelk E, Heine H, Lindner B, Inohara N, Kusumoto S, Fukase K. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:232–242. doi: 10.1039/b511866b.

- 5.Denome SA, Elf PK, Henderson TA, Nelson DE, Young KD. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3981–3993. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3981-3993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Chen L, Men H, Ha S, Ye XY, Brunner L, Hu Y, Walker S. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6824–6833. doi: 10.1021/bi0256678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ha S, Chang E, Lo MC, Men H, Park P, Ge M, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8415–8426. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Castropalomino JC, Schmidt RR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5343–5346. [Google Scholar]; (b) Debenham JS, Madsen R, Roberts C, Fraser-Reid B. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:3302–3303. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Gildersleeve J, Pascal RA, Kahne D. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:5961–5969. [Google Scholar]; (b) Taylor JG, Li X, Oberthür M, Zhu W, Kahne DE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15084–15085. doi: 10.1021/ja065907x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.There are scattered reports of other chemical glycosylations involving partially protected glycosyl donors, See Raghavan S, Kahne D. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1580–1581.Lopez JC, Agocs A, Uriel C, Gomez AM, Fraser-Reid B. Chem Commun. 2005:5088–5090. doi: 10.1039/b507468a.Plante OJ, Palmacci ER, Andrade RB, Seeberger PH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9545–9554. doi: 10.1021/ja016227r.Boons GJ, Zhu T. Synlett. 1997:809–811.Schmidt RR, Toepfer A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:3353–3356.Tanaka H, Adachi M, Tsukamoto H, Ikeda T, Yamada H, Takahashi T. Org Lett. 2002;4:4213–4216. doi: 10.1021/ol020150+.Ye XS, Wong CH. J Org Chem. 2000;65:2410–2431. doi: 10.1021/jo991558w.Green L, Hinzen B, Ince SJ, Langer P, Ley SV, Warriner SL. Synlett. 1998:440–442.Hanessian S, Lou BL. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4443–3363. doi: 10.1021/cr9903454.

- 10.Walker DA. Ph D Thesis. 2004:55–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Anderson JS, Matsuhashi M, Haskin MA, Strominger JL. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;53:881–887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.53.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leimkuhler C, Chen L, Barrett D, Panzone G, Sun BY, Falcone B, Oberthür M, Donadio S, Walker S, Kahne D. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3250–3251. doi: 10.1021/ja043849e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Barrett DS, Chen L, Litterman NK, Walker S. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12375–12381. doi: 10.1021/bi049142m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen L, Walker D, Sun B, Hu Y, Walker S, Kahne D. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5658–5663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931492100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Control experiments carried out with 14C-labeled N-acetylated Lipid II showed that both enzymes convert this substrate to peptidoglycan polymer, establishing that acetylation of the lysine amines does not prevent substrate recognition by the PGTs.

- 13.van Heijenoort J. Glycobiology. 2001;11:25R–36R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.3.25r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.