Abstract

Curriculum development in masters of public health programs that effectively meets the complex challenges of the 21st century is an important part of public health education and requires purposeful thinking. Current approaches to training the public health work-force do not adequately prepare professionals to be culturally competent in addressing health disparities. Principles of community-based participatory research highlight the importance of building relationships of mutual accountability and emphasize collegial teaching.

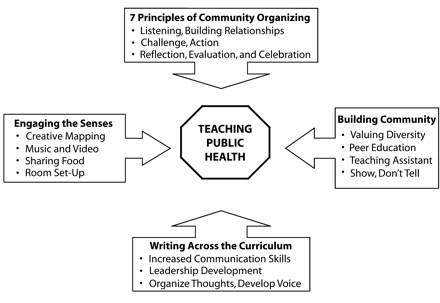

We present background and theoretical foundations for a pedagogy of collegiality and describe specific teaching methods, classroom activities, and key assignments organized around 4 essential features: principles of community organizing, building community and valuing diversity, engaging the senses, and writing across the curriculum.

THE INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE has espoused the principle that society has an interest in ensuring conditions in which people can be healthy.1 Indoctrinating the public health workforce to fulfill this interest will require a paradigm shift in teaching methods and classroom philosophies. Critiques of conventional pedagogy note that top-down approaches do not foster collegiality between students and teachers2–7 or invoke the primacy of culture in health interventions.8,9 The mission of public health is to engage social justice10,11 while applying a systematic approach to health improvement12 and reducing health disparities.13 Demographic shifts, coupled with growing evidence of health disparities between low-income multicultural populations and majority populations, underscore the need for democratic, community-based, culturally competent teaching. A pedagogy of collegiality responds to this need with an approach that values diversity of all kinds and creativity in the classroom community so that effective educational environments can be developed in which an ecological framework is learned and practiced.

A pedagogy of collegiality would transform the curriculum to include students’ voices and create a balanced environment for learning public health. The goal is to establish an educational setting that fosters an open and free exchange of ideas. “Pedagogy” captures the full experience of learning, including content, methods, student learning styles, and context, and “collegiality” refers to a relationship that embodies mutual learning and shifts the center of attention from the teacher to the students and back again so that all can become members of a community of learners. A model of progressive education since the 1970s, the collegiality approach has its roots in critical education and feminist theories. In 2000, the pedagogy of collegiality approach, introduced as a teaching model for youth–adult media production,14 began to be applied to the master of public health (MPH) program at San Francisco State University.

To engage readers in thinking purposefully about curriculum development, we discuss effective teaching processes15 for professional socialization in public health that effectively respond to the concerns cited in the Institute of Medicine’s report Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?16 and teaching techniques that create dynamic learning processes and strengthen the learning capacities of MPH students. We examine specific teaching methods, classroom activities, and key assignments organized around 4 essential features: (1) principles of community organizing, (2) building community and valuing diversity, (3) engaging the senses, and (4) writing across the curriculum.

PAULO FREIRE AND CRITICAL EDUCATION THEORY

The pedagogy of collegiality stems from a long legacy of progressive educational movements beginning with John Dewey,17 Miles Horton,18 and others.19 Paulo Freire’s2,3 theory of critical education, also known as “praxis,” emphasizes “conscientization,” the process of developing critical consciousness about oppression, building empowerment, and working toward social change.4 Freire viewed both education and research as political venues wherein power operates and reproduces itself in the social domain,20 and he wrote extensively about enriching the educational content of teaching processes through joint decision-making and collective learning. His theory and methods, developed originally from literacy work with peasants in Africa and South America, have been rearticulated in the United States by many of his students.4–7,21–29

A significant tenet of Freire’s pedagogical thought is the spirit of reinventing what it means to be a “democratic” teacher,25 that is, a teacher who facilitates critical dialogue about social conditions and motivates students to reflect on their lives and take action. In Education Is Politics,23(p26) Ira Shor noted that “students are not empty vessels to be filled with facts, or sponges to be saturated with official information, or vacant bank accounts to be filled with deposits from the required syllabus.” Students should experience education as something they do, not as something done to them.

In public health, Freire’s approach has been put into practice through community interventions,29–31 curriculum and youth development,32,33 community assessment,34–36 and evaluation research.37 Freire is credited as one of the original founders of community-based participatory research.38 In public health, community-based participatory research is a collaborative process that equitably involves all partners and recognizes the unique strengths of each.21,39 The principles of community-based participatory research 40 highlight the importance of building relationships of mutual accountability and focus on teaching public health with a pedagogy that is responsive to diversity. A recent assessment of schools of public health41 called for a greater emphasis on community-based participatory research and on providing graduates with increased skills in cultural competency, leadership, and advocacy. In combination with practice-based teaching,42 the pedagogy of collegiality is a framework capable of representing the complexity of public health43 beyond the Western paradigm.9,44

FEMINIST PEDAGOGY AND THE WOMEN’S HEALTH MOVEMENT

At the time Freire was writing Pedagogy of the Oppressed in Brazil, women in the United States were active in the women’s health and civil rights movements, exchanging experiences and exposing injustices in women’s lives through such venues as consciousness-raising workshops.45–47 Unique to the women’s health movement was interactive reflection linking health status, personal experience, and political processes.48 Feminist pedagogy arose out of this genre of consciousness-raising education with the explicit political agenda of reducing women’s isolation, building community empowerment, and shifting the site of knowledge creation.49–52

Women-centered models forge synergistic new approaches that ultimately may be the ones best suited for the complex times in which we live.49,50 Feminist educators’ methods focus on spatial dynamics in the classroom to physically address power imbalances between teacher and students.51 Feminist pedagogy assumes a nurture–neglect continuum and locates itself on the nurture side of the spectrum.53 It is rooted in relationships and encourages interaction; students examine and value their life experiences as sources of knowledge and share those experiences with each other.

Feminist educators typically cite Freire as the educational theorist whose ideas are closest to the goals of feminist pedagogy.7,51 Both frameworks raise consciousness about the social conditions that determine the distribution of privilege and oppression.54–56 Scholar bell hooks57(p71) noted that “[m]ore than any other movement for social justice in our society, the feminist movement was exemplary in promoting forms of critique that challenge white-supremacist thought on the level of theory and practice.”

APPLICATION OF THE PEDAGOGY OF COLLEGIALITY

According to the Institute of Medicine’s report on educating health professionals for the 21st century, MPH students must be taught a framework for action and an understanding of the forces that have an impact on health, and there must be an emphasis on the linkages among multiple determinants affecting health.15 In San Francisco State University’s framework, the focus of this article, public health is linked with the political activism of historically oppressed groups such as African Americans (in the civil rights movement), Mexican and Pilipino farm workers (in environmental justice), gays and lesbians (in the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS), and women and young people (in control and prevention of violence and injury). The result is that public health is taught through a lens of community organizing; MPH students shift away from a strict biomedical focus on illness and disease to an explicit language of social justice, cultural competence, and human rights (box this page).

Course Outline for “Public Health Through a Lens of Community Organizing”.

Learning Objectives

MPH students will apply concepts relating to public health as outlined in the weekly schedule below. In addition, they will:

Identify their personal value system and style of creative expression

Develop effective interpersonal and cross-cultural communication skills

Recognize concerns regarding cultural stereotypes and address them

Appreciate and apply diverse learning styles so as to be relevant both locally and globally

Weekly Schedule

Week 1: Course overview—pedagogy of collegiality

Week 2: Primary prevention and community-based public health

Week 3: Health disparities—ecological framework

Week 4: Social justice, health and human rights

Week 5: Community-based participatory research

Week 6: Ethical dilemmas in community-based public health and community-based participatory research

Week 7: Social support, social networks, and social capital

Week 8: Power, oppression, and privilege

Week 9: Social action—issue selection

Week 10: Media advocacy and media literacy

Week 11: International health—global vision, local action

Week 12: Principles of nonviolence

Week 13: Reflection and evaluation

Week 14: Celebration—student presentations

Week 15: Leading health indicator paper due

The essential features of the pedagogy of collegiality encompass a range of teaching strategies, classroom activities, and key assignments based on the application of critical and feminist theories (Figure 1 ▶ second feature, “building community and valuing diversity,” reflects a commitment to multicultural education that respects diverse learning styles and promotes open communication between the instructor and the students.

FIGURE 1—

Essential features of the pedagogy of collegiality.

The third feature, “engaging the senses,” emphasizes the use of creative arts (e.g., music, drawing, video) as original tools to garner student participation. The final feature, “writing across the curriculum,” stems from the need to strengthen graduate students’ communication skills and provides opportunities for reflection. The overall goal is for students to see themselves as health leaders with a grounding in scientific data as well as in community experience. Students have articulated their views of these essential features through their course evaluations. Excerpts from these evaluations are included here.

Principles of Community Organizing

Principles of community organizing have been developed from various sources58,59 and applied to teaching the introductory course in public health at San Francisco State University. Seven principles—listening, relationships, challenge, action, reflection, evaluation, and celebration—are central to public health practice. They allow MPH students to see themselves in a larger context as agents of change while maintaining the importance of self-reflection and one’s “place” within a community.

During the first 4 weeks of instruction, the professor leads students in a range of experiential and didactic exercises designed to enhance listening skills and build relationships. Students learn the value of developing trust and mutual respect as precursors to community assessment, program planning, and evaluation. Through the use of “dyads”—purposeful, timed, 2-person conversations—students identify the ways in which speaking is privileged over listening in mainstream culture and practice collaborative learning.60,61 In addition, they pair up to share their opinions about a particular topic before a large-group discussion. In this way, all class members have an opportunity to listen and be heard. One student recalled: “In the beginning, I did not feel comfortable with this style of teaching. I was used to listening to the lecture, reading, and writing. It seems that I was acting like a machine or a computer. But now I’ve realized my voice and it’s empowering.”

The subsequent 8 weeks are taught collegially between the professor and the students, who “co-teach” sessions on health and social justice, community-based participatory research, issue selection, media advocacy, ethics, social support, and global health. Here principles of challenge and action require students to develop and apply problem-solving and critical thinking skills. Students also study nonviolence as a health promotion practice and learn how to apply a participatory framework for personal and community empowerment. According to one student, “I appreciated the community framework that was woven throughout the entire class. We were learning about community organizing while actually being a community.”

During the final weeks of the semester, the remaining 3 principles, evaluation, reflection, and celebration, are applied. Assessment of student work includes peer reviews and written and verbal feedback. Assessment of teaching includes student evaluations as well as reflection opportunities through journal writing, small-group discussions, and process observation. The final opportunity for reflection is a community circle in which students present an object that symbolizes community or health (or both) and share its significance in relation to the class. Taking the time to develop this “sacred space” has produced mutual accountability and in fact leads to a longer term community feeling that thrives even after the end of the semester. The class concludes with a formal program of student presentations.

One of the students summed up the community organizing component as follows: “The warm community we created was the cornerstone of this experience. We could feel safe, comfortable, and able to be ourselves. I was challenged in so many ways and came away feeling inspired, energized, and passionate about public health.”

Building Community and Valuing Diversity

In the area of building community and valuing diversity, students have listed peer education and the ongoing involvement of a graduate student teaching assistant as “most helpful in building community, learning to work together, and treating each other as colleagues.” Inclusion of students in multiple roles within the classroom fosters a sense of camaraderie and cohesiveness. Students learn that they are not simply receptacles for information; rather, they are an integral part of the learning process.

Peer education values diverse learning styles and facilitates the development of partnerships between faculty members and students. The educational process is enriched when students participate and assume pedagogical roles among their peers. Peer education emphasizes critical thinking skills as well as the rhetorical skills of discussion, group collaboration, debate, and public speaking. As a means of maximizing participation, students work in groups of 3 to design and lead a weekly discussion of assigned readings in a limited time frame. One student noted: “I felt involved in every class, even when I thought I did not feel ready or willing to get involved. My involvement level was high because of the way the class was designed; there were so many opportunities to participate, I just had to.”

Graduate student teaching assistants (such as the second and third authors of this article) are essential to the pedagogy of collegiality. Teaching assistants are volunteers who receive academic credit for facilitating class discussions while providing a space for students to explore their own thoughts. They meet weekly with the professor to discuss the upcoming class and share ideas for enhancing the curriculum. Teaching assistants are mentored by the professor regarding how to embody collaborative leadership; in turn, they serve as mentors to students and exemplify civic engagement. Finally, through “show, don’t tell,” a hallmark feature of the class, the teacher and teaching assistant model the behaviors expected of students in terms of cultural competence.

Engaging the Senses

Higher education tends to focus on knowledge acquisition in complete separation from the physical and mental state required to learn well. The engaging the senses component, which addresses this “mind–body” split characteristic of higher education, challenges teachers and students to tackle health disparities through creative techniques. Opening the semester in a classroom with a look, sound, smell, and feel different than what is expected on a college campus can set the tone for a pedagogy of collegiality. Music is often playing in the background, and textiles from various cultures adorn the classroom space; a lit candle is situated next to fresh fruit, nuts, cheese, crackers, and bottled water.

Thus, the senses are captivated, and food can become a catalyst for group cohesion. Being nourished and feeding others is a form of cross-cultural learning that increases opportunities for community building. Discussions around the potluck table are relevant to learning in many ways; for example, students use the time to exchange information about assignments, personal struggles, and accomplishments. Classroom setups do not need to be quite as elaborate as that just described; the idea is for students to experience the pedagogy of collegiality not as a theory espoused by the teacher but as a practice designed to awaken their consciousness.

In the engaging the senses component, artistic expression is used to provide meaning and to facilitate students’ feelings of belonging with the community.62 For example, audiovisual media—videos and music—are used to teach key concepts, stimulate dialogue, and create interest. Media play a pivotal role in the development of pedagogical techniques that have organized and disciplined cultures both within school environments and in a broader global context.63 Visual images can be used to document and represent people, places, and health issues in innovative ways.34–36 Through videos, participants who have historically not been included “in the picture” have the opportunity to express their needs, concerns, and community assets.64 Once again, attention is paid to classroom setup, students being invited to sit in a circle or semicircle or in small groups. One student wrote that “[t]he different methods, teaching approach, and the sense of community made me feel I truly belonged. I received insight from others. I felt involved and accepted.”

Writing Across the Curriculum

According to feminist pedagogy, writing as a teaching strategy incorporates personal experience, knowledge, and problem-solving skills into concrete documents that empower through words.50 The practice of writing across the curriculum65 is emphasized throughout the semester as a key ingredient of increased communication skills. Early on, students are informed that democratic educational principles require that they share their writing. In other words, the professor will not be the only one reading their work. By the end of the semester, through “free-writes,” journal writing, and other assignments, students begin to view writing as an opportunity for leadership and a way for them to organize their thoughts and develop their voice.

Free-writes are silent group discussions that begin with an open-ended question. On a blank piece of paper, students respond to a question and take a position on the issue in question. They are encouraged to not censor themselves or worry about grammar or being correct. Free-writes are anonymous and encourage critical dialogue about social conditions. As a means of achieving maximum anonymity, the students and professor mark their papers with a personal symbol on the right-hand corner. When they have finished answering the question they raise their hand, after which they exchange papers with other class members. When students read another person’s free-write, they write comments on the paper, raise their hand, and exchange it again with another student. After the papers and ideas have circulated for 15 to 20 minutes, the professor asks the class to return each paper to its original author. After reading the responses, the class engages in open debate.

Students can use the journal-writing component to reflect on their changing membership roles and their goals in terms of professional socialization.66,67 Students are responsible for keeping a weekly journal that documents their thoughts and feelings. They are encouraged to do so in a way that fits their interests, from making simple computer notes to maintaining elaborate notebooks with drawings. Journals are private and not read by the teacher or other class members. This approach promotes open reflection without the inhibition introduced by traditional grading.

Other assignments include a team project that applies an ecological framework to a leading health indicator and the community profile, an ethnographic activity that requires students to systematically get to know a community of their choice and examine their membership role as community “outsiders” or “insiders.” Students informally interview community members and learn the importance of listening and documenting the “authentic voice” of the community in a way that acknowledges and respects cultural differences.

In addition, students map the community’s “capacity”68 (i.e., strengths and weaknesses) by drawing and writing. Through a series of questions, students begin to visualize the community they will profile, drawing it and writing a paragraph describing it. Students share their community map/drawing and read their writing out loud in dyads. The assignment is based on Freire’s recommendation that educators conduct ethnographic research in their students’ community, documenting their linguistic universe and then drawing “generative themes” and keywords from that local culture to elaborate a social analysis.2,3,28 Students have referred back to this assignment as a pivotal learning experience. For example: “It’s tremendous to look at our role as insiders or outsiders while studying about health needs and what it means to work in diverse communities. I learned as much about myself as I did about public health.”

CONCLUSIONS

Teaching public health with a pedagogy of collegiality calls for self-reflective, politically savvy faculty able to train MPH students in “real-world” applications of community-based participatory approaches. As such, effectively preparing these students can be a significant challenge. Establishing collegial relationships in instances in which there are differences in power, such as between faculty and students, is as much an art as it is a science. Although the pedagogy of collegiality has been instrumental in youth media, MPH classrooms, and other venues, public health practitioners must be cognizant of its possible limitations and challenges in other community settings.

The techniques outlined in this article require classroom spaces conducive to action-oriented teaching: Chairs must be able to move, there should be sufficient space for small-group discussion, and classroom walls need to effectively contain the sounds of laughter, music, and dialogue that are an integral part of the class. Furthermore, it is critical to recognize the institutionally imposed roles of authority that professors in a hierarchical university structure must deal with. The balance of authority/power is at the forefront of planning, implementing, and evaluating teaching. Instructors are expected to hold institutional power and be responsible for meeting academic goals as they are understood within the wider university.

MPH students are typically eager to participate in their own learning; they want to gain knowledge and skills and are prepared to actively shape the policies and programs affecting people’s lives, including their own. Educators need to teach with “a joy of living and make their classrooms model the kind of world we want to be a part of.”4(p509) As noted by Banner and Cannon,69 a joyless classroom is a huge impediment to learning. Teachers affect the social change process, one student at a time, through pedagogy. With a pedagogy of collegiality, students can move beyond learning about health disparities “out there” in the community to having actual opportunities to teach each other and become their own community in the process; at the same time, they can investigate the ways their own lives are affected by health disparities and how social forces operate in and out of the classroom.

Acknowledgments

This article was developed from our experiences in teaching the Public Health and Principles of Community Organizing introductory course at San Francisco State University. We wish to express our gratitude to our colleagues and fellow MPH students for their honesty, love, and courage. In particular, we thank Mary Beth Love, Roma Guy, Maya Scott-Chung, and Allegra Kim for their ongoing support and wise critiques of earlier versions of this article.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors V. Chavez developed the article from her ongoing work with youth media and her teaching at San Francisco State University. R. N. Turalba and S. Malik contributed to revising the article.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988.

- 2.Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury Press; 1970.

- 3.Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Seabury Press; 1973.

- 4.Darder A, Baltodano M, Torres R, eds. The Critical Pedagogy Reader. New York, NY: Routledge Falmer; 2003.

- 5.McLaren P. Life in Schools: An Introduction to Critical Pedagogy in the Foundations of Education. New York, NY: Pearson Allyn & Bacon; 2002.

- 6.Giroux H. Border Crossings. New York, NY: Routledge; 1992.

- 7.hooks b. Teaching to Transgress. New York, NY: Routledge; 1994.

- 8.Airhihenbuwa CO. Health promotion and the discourse on culture: implications for empowerment. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Airhihenbuwa CO. Health and Culture. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1995.

- 10.Beauchamp D. Public health as social justice. In: Hofricher R, ed. Health and Social Justice. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2003:267–284.

- 11.Krieger N, Birn AE. A vision of social justice as the foundation of public health: commemorating 150 years of the spirit of 1848. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1603–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 13.House J, Williams D. Understanding and reducing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in health. In: Smedley BD, Syme LS, eds. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

- 14.Soep L, Chávez V. Youth radio and the pedagogy of collegiality. Harv Educ Rev. 2005;75:409–434. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green L. From research to “best practices” in other settings and populations. Am J Health Behav. 2000;25: 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century, Institute of Medicine. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003.

- 17.Dewey J. Experience and Education. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1938.

- 18.Horton M, Freire P. We Make This Road by Walking. Philadelphia, Pa: Temple University Press; 1991.

- 19.Knowles M. The Modern Practice of Adult Education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1970.

- 20.Kincheloe J. Foreword. In: McLaren P. Che Guevara, Paulo Freire, and the Pedagogy of Revolution. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield; 2002: 105–107.

- 21.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2003.

- 22.Heaney T. Freirian literacy in North America: the community-based education movement. Available at: http://www.nl.edu/academics/cas/ace/resources/Documents/FreireIssues.cfm. Accessed April 3, 2006.

- 23.Shor I. Education is politics: Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy. In: McLaren P, Leonard P, eds. Paulo Freire: A Critical Encounter. New York, NY: Routledge; 1993:25–35.

- 24.McLaren P. Che Guevara, Paulo Freire, and the Pedagogy of Revolution. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield; 2000.

- 25.Darder A. Reinventing Paulo Freire. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press; 2002.

- 26.Giroux H. Theories of reproduction and resistance in the new sociology of education: a critical analysis. Harv Educ Rev. 1983;53:257–293. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giroux H. Theory and Resistance in Education. New York, NY: Bergin & Garvey; 1983.

- 28.Freire P, Macedo D. Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. New York, NY: Bergin & Garvey; 1987.

- 29.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q. 1988;5:379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: implications for health promotion programs. Am J Health Promotion. 1992;6:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran AN, Haidet P, Street RL, O’Malley KJ, Martin F, Ashton CM. Empowering communication: a community-based intervention for patients. Patient Educ Counseling. 2004;52:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tencati E, Kole SL, Feighery E, Winkleby M, Altman DG. Teens as advocates for substance use prevention: strategies for implementation. Health Promotion Pract. 2002;3:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallerstein N, Sanchez V, Velarde L. Freirian praxis in health education and community organizing: a case study of an adolescent prevention program. In: Minkler M, ed. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2nd ed. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2004:218–236.

- 34.Wang CC, Buris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang CC. Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. J Womens Health. 1999;8:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CC, Cash JL, Powers LS. Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through Photovoice. Health Promotion Pract. 2000;1:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallerstein N. Participatory evaluation of healthy communities. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:119–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reason P, Bradbury H, eds. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. London, England: Sage Publications; 2001.

- 39.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19: 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Selig SM, et al. Development and implementation of principles for community-based research in public health. In: MacNair RH, ed. Research Strategies for Community Practice. New York, NY: Hawthorn Press; 1998:83–110.

- 41.Shortell SM, Weist EM, Keita MS, Foster A, Tahir R. Implementing the Institute of Medicine’s recommended curriculum content in schools of public health: a baseline assessment. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1671–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Association of Schools of Public Health, Council of Public Health Practice Coordinators, WK Kellogg Foundation, Bureau of Health Professions. Demonstrating excellence in practice-based teaching for public health. Available at: http//www.asph.org. Accessed April 5, 2006.

- 43.Simpson K, Freeman R. Critical health promotion and education—a new research challenge. Health Educ Res. 2004;19:340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aronowitz S. Introduction. In: Freire P. Pedagogy of Freedom. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield; 1998:1–18.

- 45.Sarachild K. Consciousness raising: a radical weapon. In: Sarachild K, Hanisch C, Levine F, et al., eds. Feminist Revolution. New York, NY: Random House; 1979:144–150.

- 46.Ehrenreich B, English D. For Her Own Good: One Hundred Fifty Years of Experts’ Advice to Women. New York, NY: Doubleday/Anchor Books; 1989.

- 47.Worcester N, Whatley MH. Women’s Health: Readings on Social, Economic and Political Issues. 2nd ed. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt; 1994.

- 48.Evans S. Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left. New York, NY: Vintage Press; 1980.

- 49.hooks b. Feminist Theory From Margin to Center. Boston, Mass: South End Press; 1984.

- 50.Naples N, Bojar K. The dynamics of critical pedagogy, experiential learning and feminist praxis. In: Teaching Feminist Activism: Strategies From the field. New York, NY: Routledge; 2002: 9–21.

- 51.Weiler K. Freire and a feminist pedagogy of difference. Harv Educ Rev. 1991;61:449–474. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Falk-Rafael A, Chinn P, Anderson MA, Laschinger H, Rubotzky AM. The effectiveness of feminist pedagogy in empowering a community of learners. J Nurs Educ. 2004;43:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luke C. Feminist pedagogy theory in higher education: reflections on power and authority. In: Marshall C, ed. Feminist Critical Policy Analysis II: A Perspective From Post-secondary Education. Washington, DC: Falmer; 1997: 189–210.

- 54.Hurtado A. The Color of Privilege: Three Blasphemies on Race and Feminism. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press; 1996.

- 55.Anderson ML, Hill-Collins P, eds. Race, Class, and Gender. 5th ed. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth Publishing Co; 2004.

- 56.Crenshaw KW. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43:1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 57.hooks b. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. Boston, Mass: South End Press; 1989.

- 58.Wechsler R, Schnepp T. Community Organizing for the Prevention of Problems Related to Alcohol and Other Drugs. San Rafael, Calif: Marin Institute; 1993.

- 59.Midwest Academy. Organizing for Social Change. Santa Ana, Calif: Seven Locks Press; 2001.

- 60.Bruffee K. Collaborative Learning: Higher Education, Interdependence, and the Authority of Knowledge. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999.

- 61.Johnson D, Johnson F. Joining Together Group Theory and Group Skills. 8th ed. Boston, Mass: Allyn & Bacon; 2002.

- 62.Goldfarb B. Visual Pedagogy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2002.

- 63.McDonald M, Sarche J, Wang C. Using the arts in community organizing and community building. In: Minkler M, ed. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2nd ed. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2004:346–364.

- 64.Chávez V, Israel B, Allen A, et al. A bridge between communities: video making and community based participatory research. Health Promotion Pract. 2004;5:395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosen JR. Writing and Reading Across the Curriculum. 8th ed. New York, NY: Longman; 2002.

- 66.Riley-Doucet C, Wilson S. Three-step method of self-reflection using reflective journal writing. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:964–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.English LM, Gillen MA. Promoting journal writing in adult education. New Directions Adult Continuing Educ. 2001; 90(special issue):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 68.McKnight J, Kretzmann J. Mapping community capacity. In: Minkler M, ed. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2nd ed. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2004: 158–172.

- 69.Banner J, Cannon H. The Elements of Teaching. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 1997.