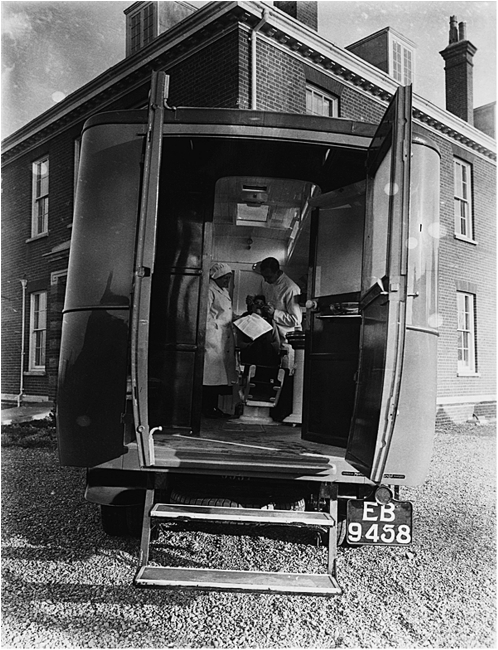

A dentist treats a patient inside the mobile dental clinic that traveled to schools in the Ely County Council region on December 8, 1931. Printed with permission of Corbis.

This issue of the Journal is devoted to “The Future of Dentistry” and looks ahead to changes in the dental profession that are necessitated by broad societal trends. For the purposes of this editorial, these trends include an aging and more diverse older population and the attendant challenges of treating increasing numbers of patients with chronic conditions who lack sufficient resources to pay for dental coverage, preventive care, and effective treatment. In particular, we expand upon the health home model previously introduced1 in light of the opportunities and challenges afforded by a rapidly shifting health care policy and practice environment. It is our express purpose to integrate oral health with general health and provide public health support to ensure the development, implementation, and sustainability of a more holistic health home model.

A DYNAMIC HEALTH HOME MODEL

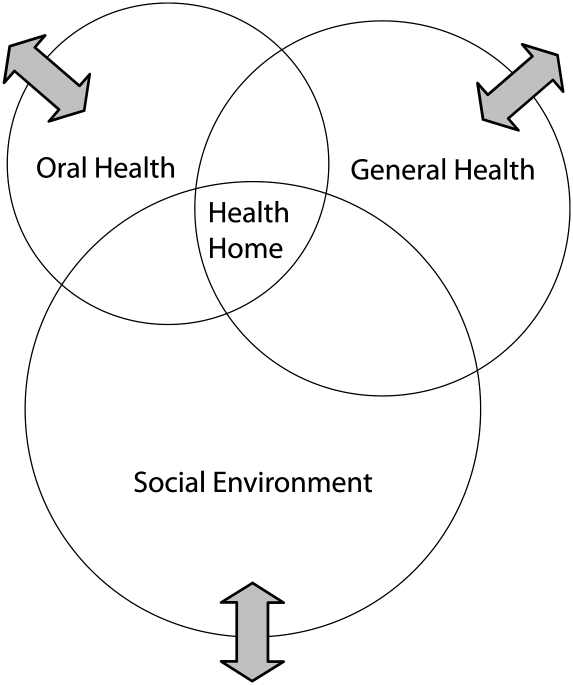

Figure 1 presents a visual representation of the health home that is depicted as the intersection of three broad domains: oral health, general health, and the social environment. This model is consonant with but broader than the medical home2,3 and health care home4,5 concepts, insofar as the focus is on health—explicitly including oral health—and not medical or health care per se. Moreover, Figure 1 expressly includes the social environment, defined by Barnett and Casper as encompassing

the immediate physical surroundings, social relationships, and cultural milieus within which defined groups of people function and interact. Components of the social environment include built infrastructure; industrial and occupational structure; labor markets; social and economic processes; wealth; social, human, and health services; power relations; government; race relations; social inequality; cultural practices; the arts; religious institutions and practices; and beliefs about place and community… .6(p465)

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the expanded health home model as the intersection of three broad domains: oral health, general health, and the social environment.

Note. Public health support is depicted by the double-headed arrows which serve to further integrate these domains through policies and practices that foster integration of patient-centered care with community-based services, namely, the health home.

Here again, the health home is consistent with the model of community-oriented primary care that engages the larger community and its resources in the delivery of health care services,7 but is expanded to include multiple scales, often acting simultaneously, including caretakers, households, families and other social networks, as well as neighborhoods, towns and cities, and regions.6

The double-headed arrows in Figure 1 represent the dynamic forces that serve to either further integrate (draw closer together) or isolate (move farther apart) the oral health, general health, and social environment domains; their overlap represents the integrated health home. Our endorsement of this concept originates with our collective yet separate experiences in delivering clinic- and community-based oral health promotion and treatment services to older adults through programs at our respective institutions. Challenges center on the regulation of dental providers through state practice acts, the structure and substance of dental insurance coverage, and reimbursement for essential services, including care coordination. Nonetheless, a critical opportunity at this time concerns US health reform and the accelerated pace of change it is engendering, including support for team-based approaches to delivering comprehensive health and social services.

HEALTH REFORM AND INTEGRATED DELIVERY SYSTEMS

As cogently explained by Sparer, the four grand ambitions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) are to (1) provide insurance coverage to more than 30 million of those who are currently uninsured, (2) slow the rising health care costs, (3) reorganize the health delivery system, and (4) improve the quality of care provided to all.8 The overarching goal is to create a more integrated and more interdisciplinary public health oriented care delivery system.8 Of particular note, the new health home option for state Medicaid programs, established by Section 2703 of the PPACA, became available to states on January 1, 2011.9 Designed for enrollees with chronic conditions, this version of the health home is intended to facilitate access to and coordination of the full array of primary and acute general health services, behavioral health care, and long-term community-based services and supports. Unfortunately, dentistry is not included in this and most other integrated care models, which is especially true for older adults. How might this be accomplished?

Lamster identified one path: the scope of practice for dentists might be reconceptualized and expanded to include a broad number of primary health care activities that may be conducted in dental settings (e.g., screening for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dermatopathology; smoking prevention and cessation activities; and obesity interventions).10 He argues that given that more than 70% of adults visited a dentist within the last year, this represents an unrealized opportunity to improve both oral health and general health.10 It must be emphasized, however, that the role of the dentist is already changing. One such role is in support of preventive care and identifying patients who may profit from enhanced prevention services, which is consistent with the current scope of practice. New models of care, such as the expanded health home as envisioned here, provide a context for reimagining the role of dental and other health professionals in meeting both patients' and society's needs.

Edelstein analyzed the merits and pitfalls of another path by asking: Should the midlevel dental provider (the dental hygienist, the dental therapist, and the dental assistant) play a larger role in providing basic oral health care, and if so, could the midlevel provider significantly improve access to oral care for disadvantaged communities?11 He concluded that only experience will determine whether this innovation in dental care delivery will ultimately support proponents' equity aspirations or be constrained by the protective concerns of the dental profession.11 In our view, the health home model is flexible enough to allow for various forms of service provision and care coordination, even as the essential functions to be included ought to build upon progress already made with the medical home model.

WHY PUBLIC HEALTH SUPPORT IS CRITICAL

As forward-thinking and laudable as the recently released Guidelines for Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Recognition and Accreditation Programs are for the health of the public, not a single mention is made of dentists or the importance of oral health.12 Public health is broad enough to encompass both the medical and dental communities, along with social services not provided by the health care system per se, (e.g., community-based nutrition and physical activity programs).

It is never too early or too late to incorporate health promotion and prevention into patient care. Nonetheless, when dealing with older adults—many of whom already suffer from chronic health conditions—it is also necessary to effectively manage multiple conditions. A public health approach encompasses the entire spectrum of services, from housing design and community planning to increase safety and prevent injuries, through hospice care that alleviates pain and suffering for the terminally ill and offers counsel and support for their families and friends.

In addition to integrating and improving systems of care for older adults, emphasis ought to be placed on enhancing social engagement and improving well-being. Public health agencies and organizations at the local, state, and national levels enjoy a long history of engaging with partners across sectors. Providing transportation geared to the abilities and needs of adults across the functional spectrum, ensuring that parks and recreational spaces include age-friendly accessibility and programming, and implementing intergenerational policies and practices that capitalize on the skills and experiences of all community members create the context in which health homes—and the people they care for—thrive.

PROMOTING HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

On January 1, 2011, the oldest members of the baby boom generation celebrated their 65th birthday. In fact, on that day, today, and for every day for the next 19 years, 10 000 baby boomers will reach age 65. The aging of this huge cohort of Americans (26% of the total US population are baby boomers) will dramatically change the composition of the country and indeed the world. At the time of this writing, just 13% of Americans are aged 65 years and older. By 2030, when all members of the baby boom generation have reached that age, fully 18% of the nation will be at least 65 years old, according to Pew Research Center population projections.13

The sheer numbers of baby Boomers reaching older ages will require rethinking and restructuring many aspects of US society, including our systems of care. To us the choice is clear. The health home approach places the emphasis on promoting health and well-being. The current fragmented medical, dental, and social care systems are difficult to navigate and create needless pain and suffering for older patients and burnout for dedicated care providers.

One of the priorities we face as educators is to better ensure that future health care professionals—including dentists—obtain the requisite skill sets to function effectively in a health home. This entails crossing traditional boundaries and accepting a very different health care delivery structure. Indeed, creating a team-based, integrated, public health–oriented care delivery system is a monumental task, but well worth the long-term effort required. By building upon the formative programs already in place and the policy opportunities of the PPACA, this is a challenge that the oral health, general health, and public health communities need to work on together.8

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported in the writing of this editorial by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (grant 1R21DE021187-01) through the project, “Leveraging Opportunities to Improve Oral Health in Older Adults.”

References

- 1.Glick M. A home away from home: the patient-centered health home. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(2):140–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sia C, Tonniges TF, Osterhus E, Taba S. History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics. 2004;113(suppl 5):1473–1478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. American Academy of Pediatrics: Policy Statement. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1):184–18612093969 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patient Care Access: An Essential Building Block of Health Reform. Bethesda, MD: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2009. Available at: http://www.nachc.com/client/documents/pressreleases/PrimaryCareAccessRPT.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant R, Greene D. The health care home model: primary health care meeting public health goals. Am J Public Health. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett E, Casper M. A definition of “social environment.” Am J Public Health. 2001;91(3):465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longlett SK, Kruse JE, Wesley RM. Community-oriented primary care: historical perspective. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14(1):54–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sparer M. Health reform and the future of dentistry. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1841–1844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Medicaid's New “Health Home” Option. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/8136.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2011

- 10.Lamster IB. A model for dental practice in the 21st century. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1825–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelstein BL. Do dental therapists constitute a potential “disruptive innovation?”: views of dental organizations, 2010. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1831–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ACP American College of Physicians Guidelines for Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Recognition and Accreditation Programs. Available at: http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/pcmh/understanding/guidelines_pcmh.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2011

- 13.Pew Research Center 10,000-Baby Boomers Retire. Available at: http://pewresearch.org/databank/dailynumber/?NumberID=1150. Accessed July 18, 2011