Abstract

Objectives. We examined patterns in cigar use among young adults, aged 18–25 years, focusing on race/ethnicity and brand.

Methods. We conducted a secondary data analysis of cross-sectional waves of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2008, using multivariate logistic regression to assess time trends in past 30 days cigar use, past 30 days use of a “top 5” cigar brand, cigar use intensity, and age at first cigar use.

Results. Cigar use has increased among White non-Hispanic men aged 18 to 25 years, from 12.0% in 2002 to 12.7% in 2008. Common predictors of all outcomes included male gender and past 30 days use of cigarettes, marijuana, and blunts. Additional predictors of past 30 days cigar and “top 5” brand use included younger age, non-Hispanic Black or White race, lower income, and highest level of risk behavior. College enrollment predicted intensity of use and “top 5” brand use.

Conclusions. Recent legislative initiatives have changed how cigars are marketed and may affect consumption. National surveys should include measures of cigar brand and little cigar and cigarillo use to improve cigar use estimates.

During the last decade, cigar industry data have demonstrated a rapid and substantial increase in cigar sales.1 In 2007, US cigar sales represented a $3.5 billion a year industry.1–3 The Maxwell Report, a trade publication that provides sales data for cigars, reported that from 1995 to 2008 annual sales of large cigars increased by 17%, sales of cigarillos increased by 255%, and sales of little cigars increased by 316%.1 By definition, a cigar is any roll of tobacco wrapped in leaf tobacco or in any other substance containing tobacco, including paper that contains tobacco or tobacco extract.3 For the purposes of taxation, large cigars are those weighing more than 3 pounds per 1000 cigars and small or little cigars are those weighing 3 pounds or less.3

Although little cigars differ from large ones with respect to weight, this is not the only, nor arguably the most important, distinction between them. Other characteristics of little cigars that set them apart from large ones are features common to cigarettes, such as size, filters, and packaging.3,4 Cigarillos are intermediate in size between a little and a large cigar, contain about 3 grams of tobacco, and are taxed the same as large cigars.2 Historically, higher rates of cigar use have been observed among men than among women and in White than in Black populations.1 However, several small studies indicate that cigarillos and little cigars have become popular among young adult populations, with some suggestion of racial/ethnic differences in use.5–7 However, these racial/ethnic differences have yet to be confirmed in large, nationally representative young adult study samples.

Cigars pose significant health risks, contributing to cancers of the mouth, lung, esophagus, and larynx and possibly the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3,5–7 Like other carcinogenic products, risk increases with consumption and depth of inhalation.8 Data suggest that little cigars may be smoked differently from large cigars, with deeper inhalation.9,10 This is likely the result of their physical similarity to cigarettes. Although there is considerable variability in nicotine content across cigar brands and types, a single cigar typically contains more nicotine than a single cigarette.3,8 Factors that affect nicotine delivery are nicotine content, cigar pH and size, and smoker inhalation patterns.3 As a result, cigars may be just as, if not more, addictive for smokers as are cigarettes.8 Additionally, there is concern over the combined use of cigars and marijuana, in which a user replaces a cigar's tobacco filling with marijuana—known as “blunting”11—or smokes a cigar after smoking marijuana to increase the effect of the latter.12

Cigar smokers may not fully appreciate the health risks associated with the use of these products. Indeed, several research studies indicate that cigar smokers misperceive little cigars and cigarillos as less addictive, more “natural,” and less harmful compared with cigarettes.13–15 Moreover, their packaging does not always carry a warning label, and so health warnings may go unnoticed by cigar users. A content analysis of the Web sites of leading health organizations indicates that limited information is provided about the harm posed by cigar use.6 Thus, the popularity of cigarillo and little cigar products may be, in part, attributable to misperceptions of reduced harm relative to cigarette smoking. Other factors related to their popularity include lower taxes for cigarillos and little cigars than for cigarettes, industry marketing practices, and possibly, the increased availability of a wide variety of flavors.13,16,17 Unfortunately, little cigar and cigarillo smokers may not recognize these products as cigars or even as tobacco products.15 Some data suggest that respondents can more reliably report their cigar brand than their cigar type; for this reason, surveys should include brand questions in addition to questions about product use.18,19 In many cases, investigators would be able to assign a product type to respondents on the basis of their reported use of the brand.

We examined the national patterns in cigar use prevalence over time among young adults aged 18 to 25 years, with an emphasis on brand and race/ethnicity. Secondarily, we examined whether demographic and risk profile factors predicted (1) past 30 days cigar use (all brands), (2) past 30 days cigar use (“top 5” brands), (3) age at which cigars were first smoked, and (4) intensity of past 30 days cigar use.

METHODS

This study consisted of a secondary data analysis of 7 consecutive, annual, cross-sectional waves of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2002–2008. The NSDUH is conducted annually by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and provides data on the prevalence and correlates of drug use in the United States among the noninstitutionalized US civilian population aged 12 years and older. Details of the NSDUH survey design are provided elsewhere.20 Briefly, participants were selected by using a multiple-stage stratified probability sample from an area frame representing the 50 US states and the District of Columbia. Selection probabilities were set to yield an approximately equal number of persons in 3 age groups: 12 to 17 years, 18 to 25 years, and 26 years old or older. Each year, approximately 68 000 completed interviews were obtained. Overall response rates ranged from 72% in 2002 to 66% in 2008.

We considered for this study only those respondents aged 18 to 25 years who self-reported as White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, or Hispanic.

Study Measures

Demographic variables. We treated age categorically in 2-year intervals as aged 18 to 19, 20 to 21, 22 to 23, and 24 to 25 years. “Younger age” refers to respondents aged 18 to 19 years. We descriptively analyzed gender, race/ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, or Hispanic), total family income ($10 000–$19 999, $20 000–$49 999, $50 000–$74 999, and ≥ $75 000), college enrollment (yes or no), and population density, and we included these as independent variables in multivariable models. We ascertained total family income using a variety of items that asked about sources and amount of income. NSDUH imputed total family income, if necessary. We considered respondents to be enrolled in college if they were aged 18 to 22 years, enrolled in school at the college level, and a full-time or part-time student. We categorized population density as those residing in a core-based statistical area (CBSA) with 1 million or more persons, those residing in a CBSA with fewer than 1 million persons, or those not residing in a CBSA.21

Tobacco use variables. The cigar use module starts with the following definition of cigars: “The next questions are about smoking cigars. By cigars we mean any kind, including big cigars, cigarillos, and even little cigars that look like cigarettes.”

The primary outcome was past 30 days cigar use, or “current use,” assessed using the following question: “Have you ever smoked part or all of any type of cigar?” followed by the question “During the past 30 days, have you smoked part or all of any type of cigar?” Other outcome measures included smoking intensity as measured by the question “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke part or all of a cigar?” and the age at which the respondent first smoked a cigar as measured by the question “How old were you the first time you smoked part or all of any type of cigar?” Cigar brand preference was ascertained by the question “During the past 30 days, what brand of cigars did you smoke most often?” This question was used to determine the top 5 brands used by respondents in the age and racial/ethnic groups included in this study. Over the 7-year study period, the top 5 brands were consistently the following: Black & Mild, Swisher Sweets, Phillies, White Owl, and Garcia y Vega. These 5 brands are cigar products sold as large cigars, little cigars, or cigarillos.1

Risk behavior variables. Risk taking was measured by means of a 4-level index using the question “How often do you get a real kick out of doing things that are a little dangerous?” with response categories of never, seldom, sometimes, and always. Past 30-day use of cigarettes, marijuana, and blunts was also examined among past 30-day cigar users (dichotomized as yes vs no).

Statistical Analysis

We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We weighted survey data to account for the probability of selection and nonresponse. In addition, we used a poststratification adjustment to align the sample distribution by demographics to the US population distribution.

The analysis data set included respondents who self-reported as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Hispanic and were aged 18 to 25 years at the time of the interview. We conducted bivariate descriptive analyses to assess the strength of association between each independent variable and the following outcomes: (1) past 30 days cigar use, (2) top 5 cigar brands reportedly used in the past 30 days, (3) number of days smoked cigars during the 30 days preceding interview (intensity of use), and (4) age at first cigar use. Denominators for the first 2 outcomes included all respondents included in the study. Denominators for the last 2 outcomes included those respondents who had smoked cigars on at least 1 of the 30 days preceding the interview.

We conducted multivariable logistic regression to assess time trends in past 30 days cigar use (overall and top 5 brands), age at which respondents first smoked a cigar, and intensity of cigar use over the 7-year study period. We analyzed age smoked first cigar and intensity of cigar use as ordinal variables with 4 levels using a cumulative logit model. We categorized age at first cigar use as 18 to 19, 20 to 21, 22 to 23, and 24 to 25 years with directionality of effect toward younger age at initiation. We categorized cigar use intensity as having smoked a cigar in the past 1, 2 to 3, 4 to 7, or 8 to 30 days, with directionality of effect toward increasing number of days smoked. We included survey year as a continuous independent variable and centered it at 2005. We made an assumption of a linear time trend; this assumption was satisfied upon formal testing. We treated all other independent variables categorically. Regression coefficients for the categorical variables represent changes in the elevations of the time trend lines. We used 1 slope coefficient to represent the time trends; they did not vary across independent variables. In a separate marginal analysis, we estimated mean current cigar use prevalence separately for the following independent variables: gender by race/ethnicity, college enrollment, past 30 days cigarette use, past 30 days marijuana use, and past 30 days blunt use. We then used annual prevalence estimates in weighted least squares regression analysis to estimate time trends. We allowed the slopes of the time trend lines to vary by levels of the independent variables.

We assessed trends over time in past 30 days cigar use by fitting straight line regression models to the estimated prevalence for each level of each of the independent variables: overall, age, gender, race/ethnicity, population density, family income, college enrollment, risk-taking propensity, past 30 days cigarette use, past 30 days marijuana use, and past 30 days blunt use. The straight line regressions were fit using weighted least squares regression as implemented in SAS/STAT version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographics, risk-taking behavior, and other tobacco or marijuana use are summarized by year in Table 1 (unweighted). Age distributions, gender, college enrollment, and educational attainment were fairly constant over time. There was a slight decline over time in the proportion of respondents who identified as White non-Hispanic, from 66.5% to 61.7%, and an increase in those who identified as Hispanic, from 14.1% to 17.0%. There was a steady decrease in past 30 days cigarette, marijuana, and blunt use across all years. We saw only minor variation in other sample characteristics over time.

TABLE 1.

Unweighted Sample Characteristics of 18–25-Year-Old Respondents From the National Survey on Drug Use or Health: United States, 2002–2008

| Sample Characteristics | 2002 (n = 17 728) | 2003 (n = 18 383) | 2004 (n = 18 475) | 2005 (n = 18 476) | 2006 (n = 17 932) | 2007 (n = 18 317) | 2008 (n = 19 141) |

| Age, y | |||||||

| 18–19 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 27.4 | 26.8 | 26.8 | 27.2 | 27.9 |

| 20–21 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 24.5 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.7 | 24.7 |

| 22–23 | 24.7 | 24.5 | 24.6 | 24.4 | 24.5 | 24.2 | 23.9 |

| 24–25 | 23.7 | 23.8 | 23.5 | 24.1 | 24.1 | 24.0 | 23.5 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Men | 46.8 | 47.9 | 46.9 | 46.8 | 48.1 | 47.4 | 47.9 |

| Women | 53.2 | 52.1 | 53.1 | 53.2 | 51.9 | 52.6 | 52.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 66.5 | 63.7 | 63.1 | 62.2 | 61.5 | 61.7 | 59.9 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 12.9 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 13.8 | 12.5 | 13.4 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 6.5 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 9.0 |

| Hispanic | 14.1 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 17.0 | 17.6 |

| Population density | |||||||

| In a CBSA with ≥ 1 million persons | 35.7 | 33.9 | 34.3 | 41.7 | 41.5 | 40.8 | 42.1 |

| In a CBSA with < 1 million persons | 39.4 | 39.8 | 38.6 | 50.6 | 50.4 | 51.8 | 50.2 |

| Not in a CBSA | 25.0 | 26.3 | 27.0 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 7.6 |

| Family income, $ | |||||||

| < 10 000–19 999 | 33.9 | 35.5 | 36.3 | 34.4 | 34.2 | 33.5 | 31.8 |

| 20 000–49 999 | 39.1 | 38.6 | 37.4 | 36.7 | 36.6 | 35.6 | 35.4 |

| 50 000–74 999 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 13.1 | 14.3 | 14.6 |

| ≥ 75 000 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 16.5 | 18.2 |

| Enrolled in college when aged 18–22 y | |||||||

| Enrolled | 28.9 | 28.6 | 29.3 | 28.9 | 28.7 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| Not enrolled | 35.0 | 35.1 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 34.8 | 35.1 | 35.2 |

| Aged ≥ 23 y | 36.1 | 36.3 | 35.7 | 36.1 | 36.6 | 36.3 | 35.6 |

| Educational attainment | |||||||

| < High school | 20.3 | 22.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 20.5 | 20.3 | 19.9 |

| High school graduate | 35.0 | 35.6 | 35.6 | 35.3 | 35.7 | 34.5 | 36.1 |

| Some college | 32.1 | 30.6 | 31.8 | 31.7 | 31.6 | 32.4 | 32.1 |

| College graduate | 12.6 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 12.8 | 12.0 |

| Risk-taking behavior | |||||||

| Never | 29.4 | 30.6 | 30.1 | 30.8 | 31.3 | 32.4 | 32.0 |

| Seldom | 36.0 | 34.6 | 34.9 | 34.7 | 34.5 | 34.2 | 34.6 |

| Sometimes | 29.4 | 29.2 | 29.7 | 29.2 | 28.4 | 28.0 | 28.1 |

| Always | 5.2 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| Usage in past 30 d | |||||||

| Cigarettes | 41.6 | 41.2 | 40.4 | 39.4 | 39.4 | 37.7 | 36.8 |

| Marijuana | 17.4 | 16.8 | 16.1 | 15.8 | 16.0 | 15.9 | 16.0 |

| Blunt | NA | NA | 9.2 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 10.1 |

Note. CBSA = core-based statistical area; NA = not available.

Descriptive Characteristics of Past 30 Days Cigar Users

Table 2 presents the bivariate associations of sample characteristics among past 30 days cigar users by year. There is a clear skew in cigar use toward younger and male respondents as well as White and Black non-Hispanic respondents. Although those not enrolled in college had higher past 30 days cigar use, differences narrowed over time. We observed markedly higher current cigar use among those reporting “sometimes” or “always” taking risks. More than one fifth and one quarter of respondents reported past 30 days cigarette and marijuana use, respectively. More than one third of respondents reported past 30 days use of blunts; however, there was a statistically significant decrease over time for concomitant blunt and cigar use (P = .03).

TABLE 2.

Past 30 Days Cigar Use Among 18–25-Year-Old Respondents From the National Survey on Drug Use or Health: United States, 2002–2008

| Sample Characteristics | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | P |

| Total | 11.2 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 11.9 | >.1 |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 18–19 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 16.3 | 15.4 | 14.1 | 15.2 | 14.2 | >.1 |

| 20–21 | 12.2 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 12.9 | >.1 |

| 22–23 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 11.9 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 10.9 | 9.9 | >.1 |

| 24–25 | 7.9 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 10.2 | >.1 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men | 17.0 | 18.0 | 20.2 | 19.1 | 19.4 | 19.1 | 18.0 | >.1 |

| Women | 5.3 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 5.7 | >.1 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 12.0 | 12.3 | 13.8 | 13.4 | 13.3 | 13.6 | 12.7 | >.1 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 13.2 | 13.2 | 14.4 | 13.2 | 13.6 | 11.3 | 11.4 | .07 |

| Hispanic | 6.8 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 9.4 | >.1 |

| Population density | ||||||||

| In a CBSA with ≥ 1 million persons | 10.4 | 10.9 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 11.9 | 11.5 | >.1 |

| In a CBSA with < 1 million persons | 11.6 | 12.5 | 13.6 | 13.4 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 12.5 | >.1 |

| Not in a CBSA | 11.9 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 11.5 | 13.5 | 10.7 | 10.6 | >.1 |

| Total family income, $ | ||||||||

| < 10 000–19 999 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 12.0 | >.1 |

| 20 000–49 999 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 10.9 | >.1 |

| 50 000–74 999 | 11.4 | 10.7 | 15.4 | 11.6 | 11.5 | 12.6 | 11.5 | >.1 |

| ≥ 75 000 | 12.8 | 15.0 | 13.8 | 13.1 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 13.7 | >.1 |

| College enrollment when aged 18–22 y | ||||||||

| Enrolled | 11.7 | 11.6 | 12.4 | 13.2 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 12.6 | .09 |

| Not enrolled | 13.0 | 14.3 | 15.4 | 14.1 | 14.5 | 14.9 | 13.4 | >.1 |

| Risk-taking behavior | ||||||||

| Never | 5.7 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.8 | >.1 |

| Seldom | 10.3 | 10.6 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 10.3 | >.1 |

| Sometimes | 15.7 | 16.1 | 19.8 | 17.7 | 17.8 | 18.0 | 17.7 | >.1 |

| Always | 24.0 | 25.7 | 28.3 | 27.3 | 26.5 | 26.1 | 25.5 | >.1 |

| Usage in past 30 d | ||||||||

| Cigarettes | 19.6 | 20.9 | 23.2 | 22.1 | 21.5 | 21.9 | 21.6 | >.1 |

| Marijuana | 27.3 | 28.6 | 32.7 | 29.3 | 29.8 | 30.2 | 27.9 | >.1 |

| Blunt | NA | NA | 41.1 | 37.7 | 36.1 | 37.2 | 33.9 | .03 |

Note. CBSA = core-based statistical area; NA = not available.

Data represent weighted prevalence estimates.

Time Trends, Top Brands, Age at First Use, and Intensity

Table 3 summarizes the findings from the multivariable logistic regression models of the 4 study outcomes. Statistically significant correlates of past 30 days cigar use included age (odds ratio [OR]18–19 y vs 24–25 y = 1.8; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.5, 2.1; P < .001); gender (ORmen vs women = 2.7; 95% CI = 2.5, 2.9; P < .001); race/ethnicity (ORNon-Hispanic (NH) Black vs NH White = 2.2; CI = 2.0, 2.4; P < .001 and ORHispanic vs NH White = 2.2; 95% CI = 2.0, 2.4; P < .001); college enrolment (ORenrolled vs not = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.78, 0.91; P < .001); risk-taking behavior (ORalways vs never = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.7, 2.2; P < .001); cigarette use (ORyes vs no = 3.2; 95% CI = 3.0, 3.4; P < .001); marijuana use (ORyes vs no = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.7, 2.0; P < .001); and blunt use (ORyes vs no = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.6, 2.0; P < .001).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression of Time Trends in Past 30 Days Cigar Use, Age First Tried a Cigar, and Intensity of Cigar Use Among 18–25-Year-Old Respondents From the National Survey on Drug Use or Health: United States, 2002–2008

| Smoked a Top 5 Branda Cigar in Past 30 Days |

Smoked a Cigar in Past 30 Days |

Age First Tried a Cigar (24–25 y, Only) |

Number of Days Smoked Cigar in Past 30 Days |

|||||

| Sample Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Year | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | .091 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | .494 | 1.05 (1.03, 1.07) | <.001 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | .877 |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 18–19 | 1.78 (1.51, 2.10) | <.001 | 1.36 (1.17, 1.57) | <.001 | NA | 1.26 (1.03, 1.54) | .028 | |

| 20–21 | 1.35 (1.14, 1.61) | <.001 | 1.16 (1.01, 1.33) | .04 | NA | 1.17 (0.95, 1.43) | .135 | |

| 22–23 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16) | .789 | 1.02 (0.91, 1.13) | .775 | NA | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) | .832 | |

| 24–25 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men | 2.66 (2.49, 2.86) | <.001 | 3.26 (3.09, 3.45) | <.001 | 1.83 (1.67, 2.01) | <.001 | 1.61 (1.46, 1.78) | <.001 |

| Women | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White non-Hispanic (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 2.17 (1.99, 2.36) | <.001 | 1.48 (1.38, 1.59) | <.001 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.04) | .173 | 4.27 (3.77, 4.84) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.84 (0.76, 0.93) | <.001 | 0.86 (0.79, 0.93) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.75, 1.02) | .093 | 1.42 (1.23, 1.65) | <.001 |

| Population density | ||||||||

| In a CBSA with ≥ 1 million persons | 0.73 (0.67, 0.80) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | .196 | 0.84 (0.75, 0.93) | .001 | 0.84 (0.73, 0.96) | .011 |

| In a CBSA with < 1 million persons | 0.87 (0.81, 0.94) | <.001 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | .505 | 0.91 (0.81, 1.02) | .103 | 0.88 (0.77, 1.00) | .041 |

| Not in a CBSA (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Family income, $ | ||||||||

| < 10 000–19 999 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 20 000–49 999 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.99) | .018 | 0.90 (0.85, 0.95) | <.001 | 1.00 (0.89, 1.13) | .98 | 1.04 (0.94, 1.15) | .438 |

| 50 000–74 999 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.03) | .171 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | .347 | 0.95 (0.81, 1.11) | .485 | 1.09 (0.96, 1.25) | .196 |

| ≥ 75 000 | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | .032 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | .844 | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | .217 | 0.95 (0.83, 1.08) | .404 |

| College enrollment, age | ||||||||

| College student 18–22 y | 0.85 (0.78, 0.91) | <.001 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.08) | .665 | NA | 0.74 (0.66, 0.82) | <.001 | |

| Not enrolled in college when 18–22 y (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≥ 23 y | 0.90 (0.79, 1.03) | .111 | 0.94 (0.84, 1.06) | .331 | NA | 0.90 (0.76, 1.06) | .218 | |

| Risk-taking behavior | ||||||||

| Never (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Seldom | 1.50 (1.36, 1.65) | <.001 | 1.57 (1.44, 1.71) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) | .522 | 0.74 (0.64, 0.86) | <.001 |

| Sometimes | 1.81 (1.65, 1.98) | <.001 | 1.93 (1.78, 2.09) | <.001 | 1.07 (0.95, 1.19) | .262 | 0.81 (0.71, 0.93) | .003 |

| Always | 1.95 (1.72, 2.21) | <.001 | 2.28 (2.03, 2.56) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.02, 1.55) | .032 | 0.97 (0.80, 1.16) | .718 |

| Usage in past 30 d | ||||||||

| Cigarettes | 3.22 (3.03, 3.43) | <.001 | 3.11 (2.95, 3.28) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.03, 1.21) | .006 | 1.20 (1.10, 1.32) | <.001 |

| Marijuana | 1.87 (1.73, 2.03) | <.001 | 1.81 (1.67, 1.96) | <.001 | 1.38 (1.22, 1.55) | <.001 | 1.33 (1.22, 1.46) | <.001 |

| Blunt | 1.78 (1.61, 1.97) | <.001 | 1.82 (1.66, 2.00) | <.001 | 1.50 (1.24, 1.82) | <.001 | 1.61 (1.42, 1.83) | <.001 |

Note. CBSA = core-based statistical area; CI = confidence interval; NA = not available; OR = odds ratio.

Top 5 brands include Black & Mild, Swisher Sweets, Phillies, White Owl, and Garcia y Vega.

Predictors of past 30 days cigar use (top 5 brand) revealed many of the same correlates as those for overall past 30 days cigar use, including the following: age (OR18–19 y vs 24–25 y = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.2, 1.6; P < .001); gender (ORmen vs women = 3.3; 95% CI = 3.1, 3.5; P < .001); race/ethnicity (ORNH Black vs NH White = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.4, 1.6; P < .001 and ORHispanic vs NH White = 0.86; 95% CI = 0.79, 0.93; P < .001); risk-taking behavior (ORalways vs never = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.7, 2.2; P < .001); cigarette use (ORyes vs no = 3.1; 95% CI = 3.0, 3.3; P < .001); marijuana use (ORyes vs no = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.7, 2.0; P < .001); and blunt use (ORyes vs no = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.7, 2.0; P < .001).

Multivariable logistic regression for age at first cigar use revealed that calendar year (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.03, 1.07; P < .001); gender (ORmen vs women = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.7, 2.0; P < .001); risk-taking behavior (ORalways vs never = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.6; P = .032); cigarette use (ORyes vs no = 1. 1; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.2; P = .006); marijuana use (ORyes vs no = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.2, 1.6; P < .001); and blunt use (ORyes vs no = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.2, 1.8; P < .001) were among key predictors. ORs > 1.0 indicate incrementally younger age at first cigar use for this ordered outcome.

Finally, key predictors of intensity of cigar use were age (OR18–19 y vs 24–25 y = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.5; P = .028); gender (ORmen vs women = 3.3; 95% CI = 3.1, 3.5; P < .001); race/ethnicity (ORNH Black vs NH White = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.4, 1.6; P < .001 and ORHispanic vs NH White = 0.86; 95% CI = 0.79, 0.93; P < .001); and risk-taking behavior (ORalways vs never = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.7, 2.2; P < .001). ORs greater than 1.0 indicate incrementally greater intensity of use for this ordered outcome.

Time Trends in Prevalence of Current Cigar Use by Race/Ethnicity

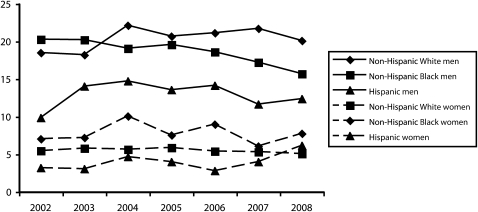

When examined by race/ethnicity and gender, the only group for which there was an increase in past 30 days cigar use during the 7-year study period was non-Hispanic White men (P = .009; Figure 1); yet, cigar use prevalence among male non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks remained substantial over time.

FIGURE 1.

Time trends in past 30 days of cigar use among 18–25-year-old respondents from the National Survey on Drug Use or Health: United States, 2002–2008.

Note. Tests for a statistically significant change in time trends reveal that among non-Hispanic White men, prevalence rates increased during the 7-year study period (P < .001). No other statistically significant changes were noted by racial/ethnic by gender groups.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study founded on US nationally representative data that documents trends in current cigar use and top brands smoked during a 7-year period. We found that a substantial proportion of young adults report current cigar smoking and that marked differences exist across racial/ethnic groups and genders. Cigar use increased over the 7-year study period among White non-Hispanic men aged 18 to 25 years. The top 5 cigar brands most frequently smoked by current cigar users in our sample are products that include little cigars or cigarillos.1 Use of the top 5 cigar brands was more prevalent among those who were younger, male, Black non-Hispanic, those with a propensity for risk behavior, and those reporting current cigarette, marijuana, and blunt use. Younger age at first cigar was associated with male gender, risk-taking propensity, and current use of cigarettes, marijuana, or blunts. Greater intensity of cigar use was observed among younger, male, non-Hispanic Black respondents, those not enrolled in college, and current users of cigarettes, marijuana, or blunts. These 4 study outcomes were selected for this descriptive epidemiological analysis to gauge the magnitude of the cigar use problem in US young adults and to better understand correlates of cigar use preference (i.e., brand), initiation, and intensity of use.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this population-based national study is the inability to directly ascertain, on the basis of brand preference alone, what type of cigar products were smoked (i.e., large, little, or cigarillos). However, the top 5 brands smoked by respondents in this study—namely, Black & Mild, Swisher Sweets, Phillies, White Owl, and Garcia y Vega—were primarily cigarillos and little cigar products.

Another limitation is that the brand smoked most often in the past 30 days may not have been the only brand smoked by a respondent. Moreover, approximately 20% of respondents selected “other” for brand preference, offering no information on whether the product was a large cigar, a little cigar, or a cigarillo.

Finally, the precision of cigar use prevalence estimates in this study may have been affected by 2 important factors. First, respondents who reported smoking cigars at least once in their lifetime, but not within the past 30 days, were not asked which brand they smoked most often. Second, those who did not report any lifetime use of cigars were not subsequently asked about brand use. This is likely to produce an underestimation of cigar use, especially given the provocative findings of Terchek et al.18 and Borawski et al.22 demonstrating an increase in self-reported cigar use when explicitly soliciting brand use information. Currently, national survey instruments that collect data on tobacco product use have key limitations. Brand data may be critical in improving cigar use estimates, including cigarillos and little cigars. Although some cigar brand data are forthcoming from the 2010 Current Population Survey Tobacco Use Supplement, NSDUH is currently the only national instrument that has publicly available data on cigar brands for current cigar users.

Impact of Legislation on Cigar Marketing

The cigar industry has historically exploited legislative loopholes to achieve continued record profits on product sales.9 In 2009, 2 legislative initiatives created a favorable environment for cigars.1,23 First, the State Children's Health Insurance Program legislation increased the federal excise tax on various tobacco products effective April 1, 2009.24 Although the new law closed a tax loophole for little cigars and equalized the federal excise tax with cigarettes, it created a tax differential between little and large cigars that benefited large cigars. Subsequently, the weight of some cigar products was slightly increased, shifting the product from the “little cigar” into the “cigar” category for tax classification purposes (i.e., more than 3 pounds per 1000), presumably as a “cigarillo,” resulting in lower retail prices. Sales of large cigars subsequently increased but were accompanied by notable reductions in little cigars,1 suggesting not a change in consumer preferences but rather a result of marketing. It bears mentioning that at the state level, there is still a considerable price advantage for little cigars. In sum, the long-term effects these taxation changes will have on cigar product consumption remains to be determined.

Second, the passage of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (HR 1256) on June 22, 2009 provided an unprecedented opportunity to the Food and Drug Administration to regulate tobacco products, although explicit restrictions on cigar manufacturers were notably absent from the act. For instance, the ban on flavored cigarettes, which took effect on September 22, 2009, did not automatically extend to cigar products, which are more heavily flavored than are cigarettes.

Conclusions

With the increasing consumption of cigar products in the United States,1 coupled with evidence of strong interest in increased sales of these products by leading manufacturers24 and a tobacco control landscape that is favorable to increased cigar consumption, there is a need to better understand who is using these products and to what extent the rates of use are increasing. The benefits of identifying what products are being smoked are multifold. Accurate surveillance to establish the potential public health burden of cigar smoking and to ensure an understanding of cigar contents and how cigar products are smoked requires measuring and tracking usage. Moreover, if products on the market (e.g., little cigars) remain less affected than other products by Food and Drug Administration regulation, taxation, or both, then tobacco product substitution might take place, shifting the public health burden from one to another product. The little cigar explosion during the time of unprecedented state cigarette tax increases demonstrates the possibility of dramatic shifts in product use. Unfortunately, cigarillos are not currently tracked and measured as a separate cigar category. Such tracking would require a legal product definition for cigarillos. Unlike the little cigar, cigarillos may be different enough in terms of content and inhalation patterns that product-specific surveillance (i.e., separate from large cigars) may be warranted.2,6

This study makes an important contribution to the literature on cigar use, underscores the need for monitoring use of cigar products type, and highlights opportunities to improve the survey instruments that are used for monitoring.

Acknowledgments

Completion of this work was financially supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (grant R03CA119799).

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because data were obtained from secondary sources.

References

- 1.Maxwell JC. The Maxwell Report: Cigar Industry in 2007. Richmond, VA: John C. Maxwell,Jr.,2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozlowski LT, Dollar KM, Giovino GA. Cigar/cigarillo surveillance: limitations of the U.S. Department of Agriculture system. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(5):424–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute Cigars: health effects and trends. : Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1998. NIH Pub. No 98-4302 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delnevo CD. Smokers’ choice: what explains the steady growth of cigar use in the U.S.? Public Health Rep. 2006;121(2):116–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boffetta P, Pershagen G, Jockel KH, et al. Cigar and pipe smoking and lung cancer risk: a multi-center study from Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(8):697–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dollar KM, Mix JM, Kozlowski LT. Little cigars, big cigars: omissions and commissions of harm and harm reduction information on the Internet. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(5):819–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez J, Jiang R, Johnson WC, MacKenzie BA, Smith LJ, Barr RG. The association of pipe and cigar use with cotinine levels, lung function, and airflow obstruction: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):201–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker F, Ainsworth SR, Dye JT, et al. Health risks associated with cigar smoking. JAMA. 2000;284(6):735–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delnevo CD. “A whole ’nother smoke” or a cigarette in disguise: how RJ Reynolds reframed the image of little cigars. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1368–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henningfield JE, Fant RV, Radzius A, Frost F. Nicotine concentration, smoke pH and whole tobacco aqueous pH of some cigar brands and types popular in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(2):163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General Youth Use of Cigars: Patterns of Use and Perceptions of Risk. Washington, DC; 1999. OEI-06-98-00030 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yerger V, Pearson C, Malone RE. When is a cigar not a cigar? African American youths’ understanding of “cigar” use. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(2):316–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolly DH. Exploring the use of little cigars by students at a historically Black university. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):1–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malone RE, Yerger V, Pearson C. Cigar risk perceptions in focus groups of urban African American youth. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:549–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page JB, Evans S. Cigars, cigarillos, and youth: emergent patterns in subcultural complexes. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2003;2(4):63–76 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delnevo CD, Foulds J, Hrywna M. Trading tobacco: are youths choosing cigars over cigarettes? Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith SY, Curbow B, Stillman FA. Harm perception of nicotine products in college freshmen. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(9):977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terchek J, Larkin EM, Male ML, Frank SH. Measuring cigar use in adolescents: inclusion of a brand-specific item. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(7):842–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Health & Human Services Office of the Surgeon General: Interagency Committee on Smoking and Health: Tobacco-Related Disparities Among Racial and Ethnic Groups. 2004. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/news/speeches/tobacco_03092004.htm. Accessed June 8, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAMHSA Office of Applied Studies, National Survey on Drug Use & Health, Methodology Reports and Questionnaires. Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/methods.cfm. Accessed June 8, 2011

- 21.US Census Bureau Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/metroareas/aboutmetro.html. June 8, 2011

- 22.Borawski EA, Brooks A, Colabianchi N, et al. Adult use of cigars, little cigars, and cigarillos in Cuyahoga County, Ohio: a cross-sectional study; Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(6):669–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg MB, Delnevo CD. Tobacco smoke by any other name is still as deadly. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):259–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Department of the Treasury Reconstituted Tobacco as Wrapper for Rolls of Tobacco. 1969. Available at: http://www.ttb.gov/industry_circulars/archives/1969/69-11.html. Accessed June 8, 2011 [Google Scholar]