Abstract

In 2009, CARE (Community Alliance for Research and Engagement at Yale University) launched a multisectoral chronic disease prevention initiative that conducts baseline data collection, interventions, and follow-up data collection to measure change. Data collection includes asset mapping to assess environmental determinants of chronic disease risk factors in neighborhoods and around schools. CARE hired 7 local high school students to conduct asset mapping; they walked more than 3000 miles and collected 492 data points. Employing youths as community health workers to collect data greatly enriched the community research process and offered many advantages. We were able to efficiently and effectively conduct scientifically rigorous mapping while gaining entry into some of New Haven's most research-wary and skeptical neighborhoods.

KEY FINDINGS

▪Engaging youths as community health workers is a successful model for collecting scientifically rigorous asset map data.

▪Key elements to the project were partnering with youth leadership development organizations, focusing on youth capacity building and mentorship, supporting youths through safe data collection with field captain supervision and team deployment, employing a comprehensive advanced outreach strategy, and using handheld computers to facilitate efficient data collection and management.

▪User-friendly, open-platform geographical information system software is needed so that youths and other community research partners can access and contribute to the mapping process for their own advocacy purposes.

CHRONIC DISEASES ACCOUNT for 70% of all deaths in the United States1 and 75% of the nation's $2.5 trillion health care expenditures2; 133 million Americans live with at least 1 chronic illness.3 In 2009, CARE (Community Alliance for Research and Engagement at the Yale School of Public Health) launched a chronic disease prevention initiative, Community Interventions for Health. New Haven, Connecticut, was the first US city to join this multinational community-based intervention study with sites in Mexico, India, and China.4 Its goal is to decrease the burden of chronic disease by addressing 3 risk behaviors: diet, exercise, and smoking. The study collects baseline data to identify chronic disease risk, conducts interventions in multiple sectors (e.g., neighborhoods, schools), and collects follow-up data to measure change. All sites have completed baseline data collection and are implementing interventions.

Asset mapping documents features of the built environment that affect health, such as access to nutritious foods and green space.5–13 Resultant maps illustrate community needs, identify assets, and engage communities in making change.9,12–19 We adapted this approach from the Community Interventions for Health initiative environmental scan methodology20 for an urban US context. With the help of local high school students, we conducted baseline asset mapping to assess environmental determinants of chronic disease in 6 low-resource neighborhoods and the perimeters of 12 randomly selected schools in New Haven.

YOUTH ENGAGEMENT AND ASSET MAPPING

Evidence shows that actively including youths adds value to community research.21–28 CARE hired 7 high school students as interns to conduct asset mapping through Youth@Work, a city program that provides work readiness development for urban youths (14–19 years) facing socioeconomic or academic barriers to postgraduation employment. In 2009, 5000 New Haven high school students applied, and 1200 were randomly selected via lottery. We partnered with The Color of Words, a youth media organization, to further screen for interest and to select and supervise the interns. CARE conducted a 3-day intensive training that incorporated research terminology and methods, information on chronic disease risk and prevention, and the use of handheld computers (Mobile Mapper 6, Magellan, Santa Clara, CA; Trimble Juno ST, Navigation Ltd, Sunnyvale, CA) loaded with software to generate global positioning system coordinates (FAST, GeoAge, Jacksonville, FL) and field survey software to collect information about mapped points (Snap Survey Software version 9, Snap Surveys Ltd, Bristol, UK).

Three adult field captains mentored and oversaw safety of their teams of 2 to 3 youths. Field captains, local residents hired through our community network, were a culinary arts teacher at a local high school, an Easter Seals workforce development coordinator, and CARE's community outreach coordinator. The youths and field captains were predominantly Black and Hispanic, reflecting the demography of the neighborhoods.

Our comprehensive community outreach strategy included meetings with neighborhood leaders, neighborhood canvassing and announcements, and news stories in the local media. Outfitted in recognizable orange CARE T-shirts, teams tackled each neighborhood sequentially, creating presence and heightening awareness. Our target was to map 1 neighborhood per week. Field captains led efforts to obtain permission from retailers to collect information about their business. Teams were denied access in only 3 of 239 approaches, demonstrating effectiveness of outreach and youth engagement.

The teams collected geocoded coordinates and survey data on pharmacies; convenience, grocery, and liquor stores; fast-food and sit-down restaurants; parks; gardens; and recreational facilities. Teams mapped the information environment (e.g., billboards) related to risk behaviors and documented marketing messages. Teams debriefed daily about process and outcomes.

Each team also conducted a neighborhood street scan, rating each of 6 neighborhoods on 15 items regarding street safety, walkability, condition of streets and sidewalks, bike lanes and paths, adherence to traffic laws, and public transportation.20 Teams compared their codes and built consensus to generate 1 score for each item in each neighborhood. Interrater reliability exceeded 75%.

In 7 weeks, the youths collectively walked more than 3000 miles and collected 492 data points. Global positioning system receivers achieved latitude–longitude coordinates within 3 to 5 meters of the target 95% of the time.29 Youth data collectors met our target: 96.7% of mapped points were accurate coordinates. The largest source of error came from 25 geographically clustered points documented in field logs but missing from the handheld computer–generated data set. The source of this error was 1 faulty handheld computer. Interns misclassified only 2 points (< 0.5%). Thus, the largest sources of error were attributable to technology rather than to human error.

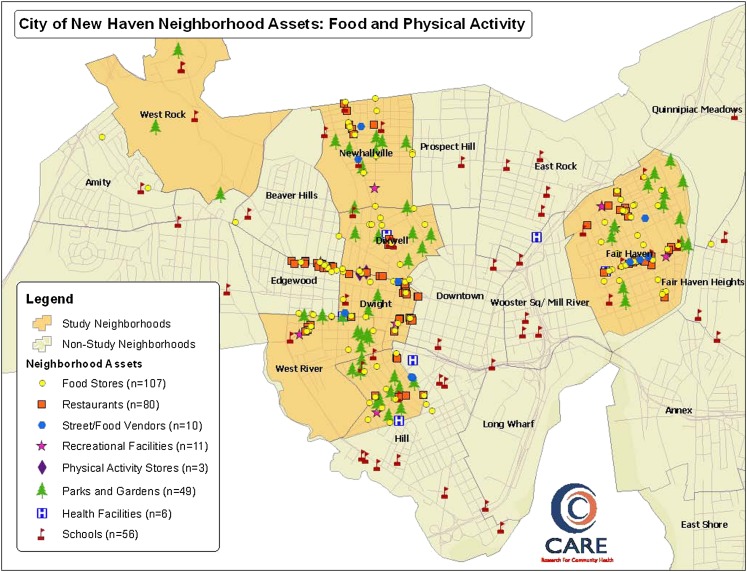

Table 1 shows characteristics of mapped points. The interns mapped 126 stores. The majority (79; 63%) were convenience stores. The second most frequently mapped stores sold alcohol and tobacco (17.5%). We observed a striking lack of supermarkets and grocery stores: only 1 supermarket and 8 small groceries. The vast majority of stores sold mostly junk food (high in fat, salt, sugar). Recreational facilities (n = 12) and sports equipment stores (n = 4) were scarce. However, teams counted 65 parks and community gardens—an asset on which interventions could be built. Figure 1 is a map generated via ArcGIS (ESRI, Redlands, CA) depicting the food and physical activity environment in our 6 study neighborhoods.

TABLE 1.

Mapped Asset Points in 6 Neighborhoods and in Perimeters of 12 Elementary Schools: Community Interventions for Health, New Haven, CT, 2009

| Asset Points | No. (%) |

| Total | 492 (100) |

| Stores | 126 (25.6) |

| Restaurants | 94 (19.1) |

| Food vendors | 10 (2.0) |

| Parks and gardens | 65 (13.2) |

| Recreational facilities | 12 (2.4) |

| Physical activity equipment stores | 4 (0.8) |

| Street scan | 90 (18.3) |

| Informational environment (signs, billboards) | 66 (13.4) |

| Public transportation hubs | 25 (5.1) |

| Original errors, corrected and included in total | 43 (8.7) |

| Missing from handheld computers | 25 (5.1) |

| Inaccurate coordinates | 16 (3.3) |

| Miscategorized | 2 (0.4) |

FIGURE 1.

Mapped points in 6 neighborhoods: Community Interventions for Health, New Haven, CT, 2009.

The interns also produced a documentary. A film production team affiliated with The Color of Words followed teams and interviewed residents about creating a healthier city. The film, 3000 Miles (http://www.vimeo.com/12392274), is a powerful advocacy tool for CARE.

DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION

Employing youths as community health workers greatly enriched the community research process. Like many universities, Yale faces town–gown tensions, particularly when conducting community research. We overcame mistrust and obtained access to businesses by hiring youths who came from and reflected the racial/ethnic makeup of the communities mapped. We efficiently and effectively conducted scientifically rigorous mapping while gaining entry to some of New Haven's most research-wary neighborhoods.

YOUTH PERSPECTIVE

I am proud to be a part of this project because my family actually suffers from diabetes. I want to find solutions for families like mine to help prevent this occurring disease and also to help people not have to actually deal with the disease. I am proud because I see the potential in each community and I hope that we start a chain reaction to make people look around and see what is wrong and to take action; that we are trying to break this cycle that we are in; to be a leader and start something beautiful.

—Karlie, aged 18 years, New Haven youth health worker

Well, when I was younger, there was like a lot of [younger] people around…. So, we used to just hang around at my house—at the park behind my house and just have fun and play games. Run around—just kids stuff really…. All that kinda changed now because there is not really that many places to go around here and do that ‘cause it's so unsafe. So yeah, I really don't know what kids do nowadays.

—Michael, aged 16 years, New Haven youth health worker

My vision for New Haven would be that when you walk into the city, you feel the love, you feel the peace and you feel the security. The youth really can make a change. Most of us don't know how or where to go. But all the youth need to know is that there is a way to change that community. We are future doctors, future lawyers, future artists, future creators. We are the future…. We walked 3000 miles this summer—through our neighborhoods, through places that we even didn't know. But that really was just a first step. The bottom line is that youth can't do it alone. We need people of all ages, of all types, to come together as equals and listen.

—Amonie, aged 15 years, New Haven youth health worker

CARE provided preliminary and on-the-job training and mentorship to prepare interns for conducting asset mapping and ensuring data quality, as well as to increase research capacity. This approach imparted professional skills in a city where research is a major industry and nurtured a cadre of future leaders who understand community-engaged research. Collaborating with experienced organizations ensured that youths had multiple opportunities for skills building and leadership development.

The budget for asset mapping was approximately $20 000, one component of a larger research grant from the Donaghue Foundation (West Hartford, CT). Interns were paid $8 to $9 per hour (25 hours/week). Other project costs were field captain wages ($15/hour; 25 hours/week), graduate-level intern ($2000 stipend), documentary production ($2500), and training, field, and outreach materials. Yale University library lent the handheld computers at no cost. This budget did not include salaries of full-time CARE staff, who provided overall project management, planning and consultation with academic researchers and community-based organizations, training development, and data analysis. Augmenting full-time staff with part-time, temporary positions permitted cost-effective data collection and provided an exciting collaborative work environment.

Handheld computers made data quickly available. Within 6 months, we produced and presented maps for community dialogues in each neighborhood. Residents were particularly interested in visual representations of their community's assets and barriers to healthy behavior. Forums also provided a platform to verify data, enriching its quality. Availability of geographical information system software was a challenge; low-cost software could not accommodate data complexity and thus limited youth involvement in mapping the collected data. ArcView 9.2 (ESRI) software produced attractive and useful maps but required user expertise.

NEXT STEPS

We are engaging residents in community-led interventions to improve health. CARE is using mapping results (together with health surveys from 1205 adults from the same 6 neighborhoods and 1094 surveys and physical measures from fifth- and sixth-grade students from the same 12 schools) to inform programmatic and policy changes to support healthier behaviors and address chronic disease disparities. For example, CARE has initiated a Healthy Corner Store pilot program in several stores adjacent to schools and intends to scale up citywide. We are working with the city to develop a comprehensive food policy to address access to healthier foods. We are exploring, with New Haven Public Schools, use of schools as community recreational centers. To track changes in neighborhood environments, follow-up mapping is planned for 2012.

This model for youth-driven asset mapping could be replicated in other communities. Key elements were partnering with youth organizations, focusing on capacity building and mentorship, supporting youths through data collection with field captain supervision and team deployment, employing a comprehensive outreach strategy, and using handheld computers to facilitate efficient data collection. Engaging youths improved outreach and community acceptance. We maintained scientific rigor and provided a professionally engaging and rewarding experience for our team of community and university investigators and stakeholders.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Patrick & Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation and the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation/Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR024139, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health).

CIH is a programme of the Oxford Health Alliance organized by the International Evaluation Coordinating Center led by Matrix Public Health Solutions. We are most grateful to the youths who worked on this project: Karlie Allen, Michael Benton, Amonie Cheeks, Jonathan Gibson, Nakia Jones, Shawanda Miller, Dennis Reynolds, Tania Rivera, Ariana Stover, and Joel Suarez. Special thanks to Maurice Williams, CARE's outreach coordinator; Bethany Davidson, MDiv/MSW, who helped coordinate the project and served as lead field captain; and Michael Kairiss, who assisted with technology needs. We also thank our other field captains, Lurettle Allen and Joseph Covington; Magalis Martinez, executive director of The Color of Words; Youth@Work staff; CARE's Capacity Building Working Group, led by cochairs Georgina Lucas, MSW, and Barbara Tinney, MSW; and Rebecca Joyce, Geographic Information System Analyst.

Human Participant Protection

This study was reviewed and declared exempt from the Yale University human investigation committee approval process.

References

- 1. Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56(10)1–120. [PubMed]

- 2. Chronic Diseases: the Power to Prevent, the Call to Control, At a Glance. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009.

- 3. Wu SY, Green A. Projection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost Inflation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health; 2000.

- 4. Duffany KO, Finegood DT, Matthews D, et al. Community Interventions for Health (CIH): a novel approach to tackling the worldwide epidemic of chronic diseases. CVD Prev Control. 2011;6(2):47–56.

- 5. Basara HG, Yuan M. Community health assessment using self-organizing maps and geographic information systems. Int J Health Geogr. 2008;7:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. Graves BA. Integrative literature review: a review of literature related to geographical information systems, healthcare access, and health outcomes. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2008;5:11. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Leslie E, Coffee N, Frank L, et al. Walkability of local communities: using geographic information systems to objectively assess relevant environmental attributes. Health Place. 2007;13(1):111–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, et al. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(4):660–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Rose D, Hutchinson PL, Bodor JN, et al. Neighborhood food environments and body mass index: the importance of in-store contents. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(3):214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. Jones J, Terashima M, Rainham D. Fast food and deprivation in Nova Scotia. Can J Public Health. 2009;100(1):32–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. McAlexander KM, Banda JA, McAlexander JW, Lee RE. Physical activity resource attributes and obesity in low-income African Americans. J Urban Health. 2009;86(5):696–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Maas J, Verheif RA, Groenewegen PP, de Vries S, Spreeuwenberg P. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(7):587–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Bodurow CC, Creech C, Hoback A, Martin J. Multivariable value densification model using GIS. Trans GIS. 2009;13(Suppl 1):147–175.

- 14. Gwede CK, Ward BG, Luque JS, et al. Application of geographic information systems and asset mapping to facilitate identification of colorectal cancer screening resources. Online J Public Health Inform. 2010;2(1):2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Ghirardelli A, Quinn V, Foerster SB. Using geographic information systems and local food store data in California's low-income neighborhoods to inform community initiatives and resources. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2156–2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Baker IR, Dennison BA, Boyer PS, Sellers KF, Russo TJ, Sherwood NA. An asset-based community initiative to reduce television viewing in New York state. Prev Med. 2007;44(5):437–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Geanuracos CG, Cunningham SD, Weiss G, Forte D, Reid LMH, Ellen JM. Use of geographic information systems for planning HIV prevention interventions for high-risk youths. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(11):1974–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Alcaraz KI, Kreuter MW, Bryan RP. Use of GIS to identify optimal settings for cancer prevention and control in African American communities. Prev Med. 2009;49(1):54–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MQ. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(2):140–147. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. Wong F, Stevens D, O'Connor-Duffany K, Siegel K, Gao Y, Community Interventions for Health (CIH) collaboration. Community Health Environment Scan Survey (CHESS): a novel tool that captures the impact of the built environment on lifestyle factors. Glob Health Action. 2011;4:5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. Mathews JR, Mathews TL, Mwaja E. “Girls take charge”: a community-based participatory research program for adolescent girls. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. Flicker S, Guta A, Larkin J, et al. Survey design from the ground up: collaboratively creating the Toronto Teen Survey. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(1):112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23. Flicker S. Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the Positive Youth Project. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35(1):70–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24. Harper GW, Carver LJ. “Out-of-the-mainstream” youth as partners in collaborative research: exploring the benefits and challenges. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26(2):250–265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Branch R, Chester A. Community-based participatory clinical research in obesity by adolescents: pipeline for researchers of the future. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2(5):350–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Amsden J, VanWynsberghe R. Community mapping as a research tool with youth. Action Res. 2005;3(4):357–381.

- 27. Powers JL, Tiffany JS. Engaging youth in participatory research and evaluation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(6 Suppl):S79–S87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28. Chen P, Weiss FL, Nicholson HJ, Girls Incorporated. Girls Study Girls Inc.: engaging girls in evaluation through participatory action research. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;46(1–2):228–237. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. GPS Navstar Global Positioning System. Global Positioning System Standard Positioning Service Performance Standard. 4th ed. Washington DC: Department of Defense; 2008.