Abstract

Malaria poses a significant public health burden in the remote areas of western Cambodia, where access to health services and information is limited. Recognizing the potential of village malaria workers to reach these communities, the US Agency for International Development-funded Malaria Control in Cambodia project used a multipronged approach to strengthen the village malaria workers network. As a result, the proportion of confirmed malaria cases treated by village malaria workers has doubled during the past 2 years, significantly increasing the numbers being properly diagnosed and treated. Key to the program's success has been the integration of village malaria workers with public health facilities, improved patient access to prompt diagnosis and treatment, and resolution of systemic barriers such as logistics for rapid diagnostic tests.

KEY FINDINGS

▪Strengthening the system of village malaria workers can have significant results in increasing early diagnosis and treatment of malaria.

▪Village malaria workers can be trained to perform rapid diagnostic tests and malaria smears and provide appropriate antimalarial treatments at the community level.

▪Linkages with the public health sector are critical for ensuring up-to-date malaria information for the village malaria workers, improving the flow of supplies to and community data for the health centers, and procuring supplies.

CAMBODIA HAS A MALARIA incidence rate of 6.26 cases per 1000 inhabitants (2009).1 The transmission of malaria is particularly high in the western provinces near the Thai border, which have poor road conditions, limited means of communication, and a high number of migrant workers because of cross-border economic activities. In the context of high malaria incidence in remote communities, the role of village malaria workers in providing malaria services is critical. The National Malaria Center (CNM) requires that village malaria workers be present in malaria-endemic villages more than 5 kilometers from health facilities or more than 1-hour walking distance. Village malaria workers reach out to community members with malaria information, provide mosquito nets, diagnose malaria cases with rapid diagnostic tests, provide malaria treatment, and refer severe malaria cases to health facilities.

STRENGTHENING THE VILLAGE MALARIA WORKERS NETWORK

The US Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded Malaria Control in Cambodia (MCC) project implemented by University Research Co. (URC) began working with the CNM in September 2007, adopting a multipronged approach to strengthen the network of village malaria workers in 2 provinces in Containment Zone 1, where resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to artemisinin has been documented, and 2 provinces in Zone 2, where resistant parasites have yet to be formally detected.

Improved Recruitment

URC-MCC and the CNM recruited 532 village malaria workers to work in malaria-endemic villages. In many cases, both a male and a female village malaria worker were trained for each site, often a husband and wife team, resulting in more consistent services. Village malaria worker selection criteria were (1) residence in the community, (2) reading and writing skills, (3) interest in volunteering, and (4) being elected by the community. URC-MCC supported the village malaria workers’ effort to more actively offer their services to the community through signboards and posted timetables (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Signboard indicating village malaria workers’ location.

Training on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment

URC-MCC, in close collaboration with the CNM, provided training for the village malaria workers between January 2008 and June 2009. Village malaria workers received information on malaria prevention; were trained to recognize malaria signs, symptoms, and complications; and learned how to engage in community networks to promote the use of public health services for seeking early care and treatment. The village malaria workers also learned how to use rapid diagnostic tests, provide antimalarial drugs according to the national treatment guidelines, and refer severe malaria cases to the nearest public health facilities.

Strengthened Interaction With Health Centers

URC-MCC supported monthly meetings between village malaria workers and public health center staff to exchange information about malaria. The meetings, organized at each health center, involved data reporting from the communities and distribution of health education tools, rapid diagnostic tests, and drugs to the village malaria workers. Approximately 500 village malaria workers attended the meetings each month.

Improved Supply of Malaria Drugs and Commodities

Village malaria workers’ activities were limited by the irregular supply of antimalarial drugs and rapid diagnostic tests from the CNM. URC-MCC and the CNM organized a workshop bringing together health managers and logistics staff from provincial and operational district health offices to develop a process for including supplies for village malaria workers in the quarterly shipments from the Operational District Office to health facilities. URC-MCC also worked with health centers, operational districts, the CNM, and the Central Medical Store to improve forecasting and reduce supply interruptions. As a result, the supply of rapid diagnostic tests, drugs, and health education tools to village malaria workers improved significantly.

DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION

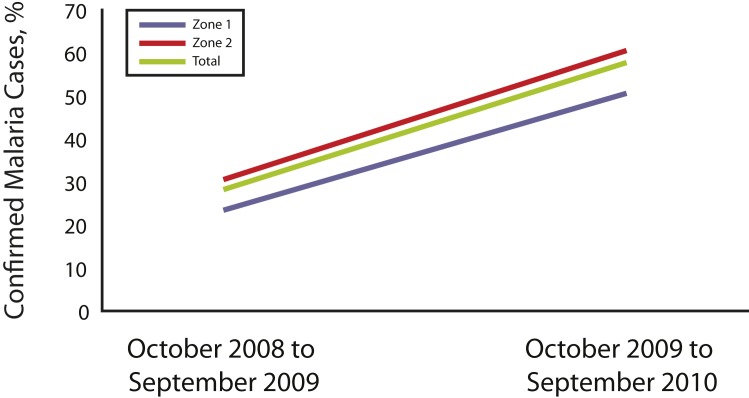

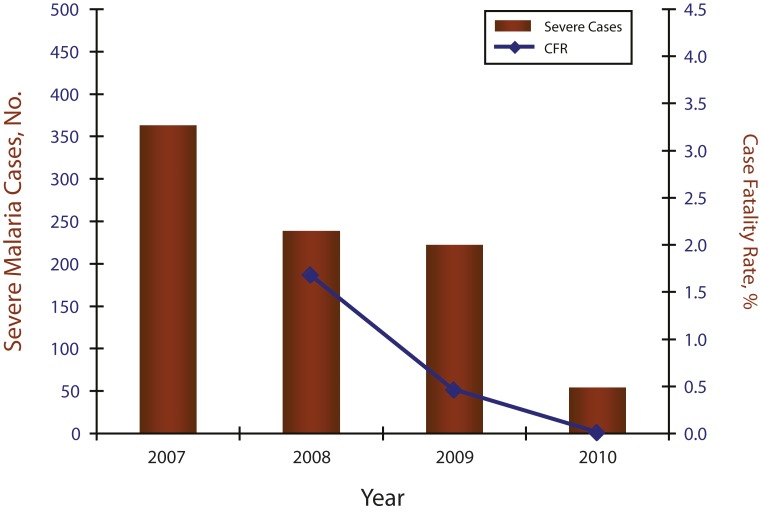

During the 2 years that village malaria workers strengthened their network, the proportion of confirmed malaria cases treated by village malaria workers has doubled, increasing from less than 30% of confirmed malaria treated by village malaria workers to almost 60% (Figure 2). Since the deployment of village malaria workers in Zone 1 in 2008, the number of severe malaria cases and the malaria case fatality rate reported by health centers have declined, indicating that malaria is being diagnosed and treated earlier (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of confirmed malaria cases treated by village malaria workers in the remote areas of western Cambodia, October 2009–September 2010.

FIGURE 3.

Severe malaria and case fatality rate reported by public health facilities, Containment Zone 1, western Cambodia, 2007–2010.

Challenges

The main challenge was village malaria worker turnover and low motivation. Use of husband and wife teams was an effective solution because they could support each other and effectively reach both men and women. Village malaria workers also were motivated by interacting with village malaria workers from other villages and with health center staff at monthly meetings. They received per diem for the meeting and were reimbursed for transportation costs. The government also agreed to provide free health services to village malaria workers and their families. Motivation also was increased by recognizing the contribution of village malaria workers at annual CNM conferences and World Malaria Day events.

Keys to Success

Linking village malaria workers with the health center in the catchment area was very effective. During monthly visits, the village malaria workers received guidance from the health center staff, could clarify concerns and questions, and obtained malaria information, education, and communication materials and diagnostic tools. The health center staff gained information and data about malaria in the community. Although building the relationship took some time, the arrangement was beneficial to everyone.

To work effectively, village malaria workers required a consistent supply of rapid diagnostic tests. Resolving logistics bottlenecks, however, was beyond the scope of village malaria workers and of health center staff and required higher-level support from URC-MCC, CNM, and the Central Medical Store. Once logistics issues were resolved, village malaria workers could work much more effectively.

NEXT STEPS

The results of strengthening the village malaria workers network for malaria control in remote areas are promising, and the multipronged approach is likely to be scaled up to other remote areas. Long-term sustainability, however, will require ongoing commitment from the CNM for integration of village malaria workers into the public health system and for fostering ongoing support of health center staff. Because of their success, the role of village malaria workers may be expanded to include treatment of diarrhea and acute respiratory infection. Further expansion, however, should be carefully planned given the challenges with maintaining motivation.

Acknowledgments

The Malaria Control in Cambodia project was funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID)/Regional Development Mission for Asia.

Appreciation is expressed to Thitima Klasnimi and Neeraj Kak for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Note. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed because the article is a description of program activities and did not involve research with human subjects.

References

- 1. National Program of Parasitology, Ontomology, and Malaria Control. Annual Progress Report. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: National Malaria Center; 2010.