Abstract

There are currently 7175 farmers’ markets in the United States, and these organizations are increasingly viewed as one facet of the solution to national health problems. There has been a recent trend toward establishing markets on medical center campuses, and such partnerships can augment a medical center's ability to serve community health. However, to our knowledge no studies have described the emergence of a market at a medical center, the barriers and challenges such an initiative has faced, or the nature of programming it may foster. We provide a qualitative description of the process of starting a seasonal, once-a-week, producers-only market at the Pennsylvania State Hershey Medical Center, and we call for greater public health attention to these emerging community spaces.

Farmers’ markets are defined as recurrent organizations at fixed locations where vendors sell farm products and other goods.1 According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), 7175 markets operate in rural and urban areas2 serving public health in multifaceted ways: increasing fruit and vegetable consumption,3 revitalizing neighborhoods, strengthening local economies, promoting a sustainable environment through the consumption of local foods,4 empowering community members to learn more about the items they buy (e.g., what chemicals went into their production, how many miles the food traveled, how the soil was treated, and how the animals were raised), and encouraging social interaction and physical activity.

Markets are increasingly viewed as one facet of the solution to national chronic health problems. The White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity Report to the President has sought a greater role for farmers’ markets in contributing to a reduction in childhood obesity,5 and first lady Michelle Obama has promoted markets as part of her “Let's Move” initiative.6 The president's 2011 budget proposes an additional $5 million investment in the Farmers Market Promotion Program at the USDA, which provides grants to establish and improve access to farmers’ markets.7 The federal government is also investing millions of dollars to increase the number of farmers’ markets that participate in supplemental nutrition programs, with the goal of reducing “food deserts” in inner-city and rural communities.8,9

Within this national movement, there has been a more recent trend of establishing farmers’ markets on medical center campuses—thus creating partnerships that strengthen the abilities of medical centers and clinics to provide complete, patient-centered care10 and serve community health.11 However, there is a paucity of qualitative studies describing how individual markets have emerged in nontraditional settings such as medical centers, the barriers and challenges those initiatives have faced, and the nature of programming that can occur in these unique spaces.12 We have provided a qualitative description of the process of establishing a seasonal, once-a-week, producers-only farmers’ market at the Pennsylvania State Hershey Medical Center (PSHMC) in Hershey, Pennsylvania, which we established in spring 2010. We define the rationale for initiating a market on an academic medical center campus, discuss key lessons learned and barriers faced, and describe the nature of public health–oriented programming that occurred at the market and could be replicated at other medical center–based markets. Although each new farmers’ market emerges in specific settings and adapts according to local needs, some general principles salient to the experience of the Farmers’ Market in Hershey are likely applicable to similar efforts on other medical center campuses. We have described the process of establishing and evaluating the Farmers’ Market in Hershey to facilitate the growth of similar medical center farmers’ markets in other regions.

RATIONALE FOR ESTABLISHING MEDICAL CENTER FARMERS’ MARKETS

Historically, there have been numerous efforts to promote healthy eating and lifestyle practices in community settings such as supermarkets, schools, and worksites, as well as through community marketing campaigns.13–15 Although these interventions have reported promising short-term effects, sustaining these initiatives has remained challenging. Once funding to conduct interventions has ended, there has often been a lack of sufficient personnel, resources, or incentives to continue health-related programs. To alter dietary and lifestyle choices over the long term, there is a need to establish settings that can provide a more sustainable supply of personnel and resources to conduct diet and lifestyle change programs.

Farmers’ markets on medical center campuses may provide a promising venue for promoting healthful lifestyle changes. The mission of PSHMC—as with any medical campus—is not only to treat illness but also to promote wellness for patients, employees, and the surrounding community. As venues that are visited by hundreds if not thousands of workers, patients, and community members each day, medical centers can provide a practical site for markets by ensuring a steady customer base. Medical center campuses can also frequently provide a sustainable supply of students and residents interested in further developing their health screening and program management skills, researchers interested in evaluating market-based initiatives, and volunteer staff committed to improving community health. The proximity of medical center–based farmers’ markets to these diverse labor sources strengthens the likelihood of maintaining a sustainable supply of qualified staff for lifestyle change initiatives. Market vendors themselves—who can benefit economically from participating in the market—may provide another source of health-related programming (e.g., demonstrating the preparation of healthy foods, distributing recipes, and participating in federal nutrition supplementation programs). The potential for mutual benefit—including meeting the educational, public service, and research mission of academic medical centers and providing economic and social benefits for local farmers—is likely to contribute to the sustainability of market-based health initiatives on medical center campuses. The primary objectives of the Farmers’ Market in Hershey were to

increase community access to healthy, locally grown foods;

support local farmers engaged in sustainable practices by creating another venue to sell their goods;

establish opportunities for community wellness partnerships (e.g., free health screenings, public education about prevention and nutrition);

build a community space for interaction between employees of a large medical center and residents from surrounding neighborhoods; and

pay homage to the agricultural heritage of the land surrounding PSHMC.

We established that the market should be producers only and organic, although this commitment yielded unforeseen challenges. Specifically, because some farmers perceive the process of registering as an organic farmer with the USDA as onerous, many local farmers choose to use organic practices without seeking formal approval. Therefore, we settled that the market would aim to be 80% organic (on the basis of farmers’ practices rather than their formal status as USDA organic) and would offer fruits and vegetables, dairy products, meats, baked goods, coffee, and specialty items such as spices, honey, sauces, flowers, and prepared foods sourced from within an average 25-mile radius. This distance was considered sufficiently “local” to minimize the use of gasoline, render the carbon footprint of most products negligible, and maximize the freshness and nutritional quality of the foods. We also agreed that community wellness programming—a weekly curriculum of medical professional–led activities that promoted public health education—would be a major strategic focus that would differentiate the Farmers’ Market in Hershey from other local markets. The overarching vision for the market was to combine agricultural, medical, and community resources so that the Farmers’ Market in Hershey would significantly contribute to the long-term health of the region and model how a partnership between a medical center and a farmers’ market could provide more comprehensive care for patients and families.

STEPS TO ESTABLISHING THE MARKET

Although the PSHMC administration was receptive to our vision of providing comprehensive patient care, we knew little about how to design a market on a medical campus. What proved most useful during the 5-month market-planning phase was reaching out to existing markets located within medical centers. The Cleveland Clinic, which established its farmers’ market in 2008, provided informal consultation about the optimal size, scheduling, and logistics of markets, as well as anecdotes about what worked well (e.g., the hospital cafeteria contracting to purchase leftover produce each week, having free health screenings), what needed improvement (e.g., increasing customer diversity), and how a leadership structure should function (e.g., clearly delineating roles and responsibilities for a market director and manager). Although the Cleveland Clinic's market was located on an urban campus unlike PSHMC's rural setting, many of the principles underlying their market operations applied to the Farmers’ Market in Hershey.

Once we had established basic knowledge about the structure and governance of medical center farmers’ markets, we obtained further information about region-specific logistics from market masters at area farmers’ markets. In reaching out to these market masters, it was imperative for us to emphasize that the Farmers’ Market in Hershey did not intend to compete with their markets and for us to establish working partnerships (i.e., the Farmers’ Market in Hershey would promote other local markets that were open on different days). Local market masters provided indispensable information about region-specific logistics: optimal market opening hours; appropriate marketing strategies; material needs such as electricity, tents, and tables; maintenance considerations such as trash removal; budget development; liability insurance issues; and zoning requirements. They also provided contact information for potential vendors and form letters for vendor recruitment. Moreover, some market masters shared their market's vendor bylaw documents, which we used to create official bylaw templates for the Farmers’ Market in Hershey. This bylaw document contained contractual agreements on such topics as the 80% local and organic rule, permitted items of sale, season market fees, vendor compliance with regulatory agencies, requirement of vendor liability insurance, vendor voting rights on market issues, directions for product drop-off and stand setup, storage rules, agreement to display products rain or shine, process for handling vendor complaints, and rules for termination of the market if it did not meet minimum productivity standards. We distributed these bylaws in preliminary proposals to PSHMC leadership and other key constituents. Perhaps most importantly, these market masters provided a sense of realism: the market in Hershey needed to be accommodating and not pose competitive or existential threats to other markets while leveraging its proximity to a world-class medical center to fill a unique niche in the community.

Obtaining Medical Center Leadership Buy-In

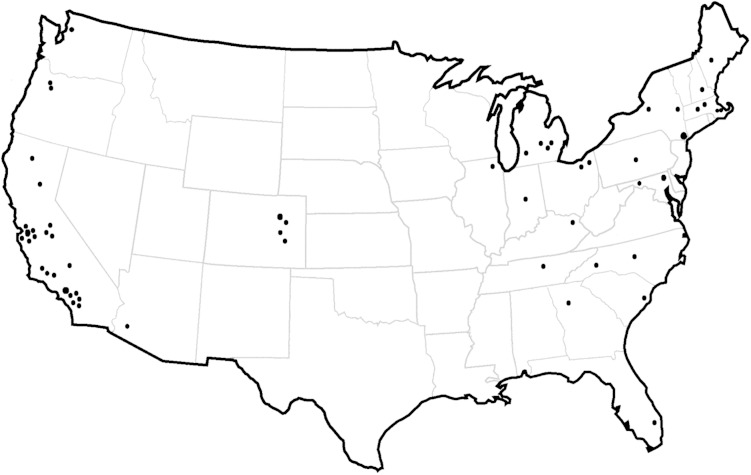

Information gathered from other medical centers and existing local markets in southeastern Pennsylvania informed a 2-page action plan outlining the market's purpose, objectives, and vision for serving regional health; proposed organizational structure; marketing strategy; and campus partners that had committed to collaborative community wellness programming. After a 3-month review period by leadership at PSHMC, administrators in the finance and facilities departments expressed concern that the Farmers’ Market in Hershey could exact unanticipated financial costs from PSHMC while creating logistics problems for maintenance staff. To address the first concern, we emphasized that the model—as with many farmers’ markets—was cost and revenue neutral; regarding the second concern, we wrote vendor bylaws requiring vendors to remove all waste to avoid burdening PSHMC with cleanup. It was also helpful for us to compile and distribute to the executive director and chief executive officer a list of farmers’ markets around the nation that were located on hospital or research park campuses (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Known farmers’ markets on US medical campuses: 2011.

Note. Markets were identified through the US Department of Agriculture National Farmers Market Directory (https://apps.ams.usda.gov/FarmersMarkets), using the search terms “medical” (8 results), “hospital” (17 results), and “clinic” (3 results), as well as through the Kaiser Permanente listing11 (47 results). Internet searches using the terms “farmers market,” “medical center,” “hospital,” and “clinic” identified an additional 12 markets. Not shown: Hawaii (4 markets).

This list normalized the concept of allowing a market to coexist on a medical campus while demonstrating that some of the major academic medical institutions in the United States were already supporting markets of their own.

Addressing Zoning Regulations

Once we gained permission from PSHMC, it was necessary to research zoning issues at city hall and to formally appeal to the local zoning committee, a process that took another few months. Issues that were discussed—and would likely emerge in any farmers’ market initiative on or around a medical center campus—were land use, parking and pedestrian safety, yard areas, compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and signage requirements.

Understanding the Customer Base

To survive, markets must meet specific needs within the communities they serve. To assess customer demand, we developed an online survey (using SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA) and advertised it to PSHMC staff on the medical center's main internal Web page and to the general public through e-mail discussion groups of community organizations. Nearly 2200 PSHMC staff members (out of approximately 8000) responded to an 8-question survey that asked whether they would attend a medical center market, which days and times would be convenient, what their potential modes of transportation to the market would be, and whether they would be interested in purchasing and selling different market products. We asked those wishing to be kept apprised of market news and information to provide their e-mail address. This e-mail list became the basis for a weekly newsletter that we sent out during market season.

In addition to the mandate from 98.8% of respondents who indicated that they would be inclined to buy products from a farmers’ market located at PSHMC, survey data helped refine planning and logistics. Overwhelmingly, respondents wanted a market later in the week and indicated that they would prefer to shop later in the day, once per week. Produce was the most desired product, but significant demand was registered for all products. Nearly half of respondents indicated that they were likely to walk to the market, which raised interest in coupling the market with initiatives to promote physical activity.

Forming a Market-Governing Association

Once PSHMC and the local zoning boards had approved the market, we recruited local vendors producing products that matched the market's mission. Ten core vendors were established (given space constraints and advice from market managers about ideal starting size). We formed a market association in which vendors were given the ability to vote to amend existing bylaws and to establish leadership positions. This process was helpful in calibrating the original market action plan to meet the needs of farmers. Specifically, we established a more desirable vendor fee structure (i.e., a larger flat fee rather than a smaller flat fee with weekly commissions) and lowered opening times from 7 hours to 4 hours on the dual rationale that a shorter opening time would maximize turnout and that it would be easier to extend hours later than to reduce them. The market association provided ongoing leadership on issues that arose throughout the opening season, meeting once per month after market day. The market director and manager cofacilitated meetings, and the manager also collected the minutes. Each vendor had 1 vote in proceedings, and vendors elected 1 association leader to liaise with the market manager and director.

Informing Medical Professionals

Although news about the Farmers’ Market in Hershey spread by word of mouth, we made a concerted effort to educate the medical community about the potential public health value of the Farmers’ Market in Hershey. We identified contact persons from key institutes within PSHMC and sent them e-mails with a 1-page brochure describing the market. Most agreed to distribute information to patient populations by placing literature in waiting rooms or sending information through e-mail lists. We also used internal e-mail discussion groups to inform all PSHMC physician and nursing staff about the market while asking them to educate their patients about the opportunities to access local fresh foods (dubbed “prescription produce”16) and participate in free wellness programming at the market. Throughout the market season, the market director sent weekly newsletters to these constituents to provide ongoing education about featured produce and prevention programming that could be promoted to patients. We also urged employees to walk to the market through a 10 000 steps a day campaign spearheaded by the University Fitness Center. The market was located a half mile from the center of campus, allowing the average pedestrian customer to walk approximately 2500 steps there and back.

Building Partnerships for Community Wellness Programming

The key differentiating point for a farmers’ market located on a medical center campus is the proximity of experts in areas such as medicine, public health, nutrition, kinesiology, and psychology, which enables the market to serve as a credible community venue for public health promotion. We reserved 3 booths at the market for weekly community wellness outreach and engaged PSHMC employees in conceptualizing and conducting this programming. At the first booth, “Know Your Numbers,” student and faculty volunteers from the College of Medicine and School of Nursing provided free weekly health screenings (blood pressure, body mass index, osteoporosis, vision, and skin cancer risk) to shoppers as well as information about chronic disease prevention. These volunteers also provided health-themed games for children.

At the second booth, “Preventive Health,” medical professionals from multiple backgrounds, who had submitted ideas for programming, rotated weekly and provided free information on such topics as stroke risk, diabetes, nutrition and activity promotion for children, breast cancer, and head injury prevention. The Preventive Health booth also featured “fruits and vegetables of the week” with recipe cards for shoppers with suggested uses for the featured weekly produce.

A third booth, “Community Programming,” featured programming from nonmedical specialists in the community who sought to contribute to the market's vision of furthering wellness. Community programming included free workshops on holistic health, Reiki demonstrations, yoga and tai chi workshops, acupuncture information, aromatherapy, and other integrative medicine approaches, as well as information from local fitness centers, businesses, and environmental groups.

In addition to the programming at each booth, guest chefs from nearby restaurants and local certified organic chefs held several free classes on preparing healthy meals with organic ingredients from the market. Local musicians also performed at the market each week. We made all community connections through word-of-mouth, person-to-person networking or the social networking Facebook page that we developed for the Farmers’ Market in Hershey.

Marketing the Market

We created a marketing committee in partnership with the marketing department at PSHMC to establish a marketing strategy. The marketing plan encompassed 3 phases: (1) development of logo, branding, and distribution materials; (2) development of a marketing strategy within the hospital and surrounding community; and (3) development of an online and social media presence.

Phase 1 involved defining the distinguishing thematic elements of the Farmers’ Market in Hershey and combining them into the market logo. Because the Farmers’ Market in Hershey was located on a medical campus and had the potential to more robustly support community wellness programming than did other area markets, we sought to capture this unique feature with logo and branding efforts. Phase 2 required reaching out to potential customers to educate them about the market. For PSHMC staff, we accomplished this by launching in-house advertising through campus publications. We also created a weekly e-mail discussion group from the approximately 1500 e-mail addresses we garnered from the online survey.

Further grassroots community outreach involved contacting local media outlets (newspapers, radio, and television), neighborhood newsletters, local advocacy groups, day care centers, senior centers, local politicians, and local barbershops. We used mailing lists of local ministries and businesses that supported the market, and market leadership and volunteers reached out to local politicians from heavily agricultural districts who supported local farmers.

Phase 3 involved establishing a Facebook group page, a Twitter account, and a newsletter strategy as well as assigning responsibility for regularly updating these materials. With the exception of design and server charges associated with the Web site, communication tools such as Facebook, Twitter, and newsletters were free interfaces that connected market leadership with thousands of community members who could be reached through simple status updates and e-mail blasts, all of which placed a minimum time burden on market leadership. Because of the viral networking effect of Facebook, the group page accumulated 1000 fans in less than a month and became an influential means of 2-way communication with customers, enabling staff to promote market events and receive customer feedback. Furthermore, we registered the Farmers’ Market in Hershey in farmers’ market directories and on Google Places so that it would appear on Google map searches and on online customer review sites such as Yelp.

Serving Diverse Populations

A lack of markets close to home and a lack of transportation to markets have been identified as primary barriers among underserved populations who wish to use farmers’ markets.17 However, markets that engage persons from underserved areas and increase access to fruits and vegetables and nutrition education can improve dietary quality and increase Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program participation.18 Medical centers such as the Cleveland Clinic are located in inner-city “food deserts,”19 which enables their markets to more readily engage underserved groups at the market. However, centers such as PSHMC that are located in more rural or affluent areas, have greater challenges in developing a strategy to serve a more diverse demographic.

As the 2010 White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity Report to the President encourages markets to use Woman, Infants, and Children cash value vouchers, Seniors Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program coupons, and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits to provide incentives for healthy eating among disadvantaged groups,5,20 we began registering the Farmers’ Market in Hershey with these federal programs to benefit lower-income PSHMC employees and community members. We will also make efforts to subsidize mileage for inner-city organizations (e.g., churches, community centers) that can transport individuals to the market. We have connected vendors at the Farmers’ Market in Hershey with local nonprofit organizations that buy leftover produce from farmers’ markets and distribute it to soup kitchens, homeless shelters, halfway homes, and community clinics in underserved areas. Plans are under way to further develop outreach into impoverished areas by establishing mobile markets that can distribute produce and provide preventative programming to “food desert” neighborhoods several miles from the market.

Serving a diverse demographic also entails reaching out to patients at the medical center. We hope that cafeteria services at PSHMC will purchase farmers’ market produce and integrate healthier foods into patient meals. The program Stanford Hospitals and Clinics Farm Fresh21 has created an inpatient menu option that uses exclusively organic ingredients from local sources. The philosophy undergirding this program is that healthy food is an important part of the healing process for patients and that locally sourced products can help serve a medical center's larger mission of health promotion.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

More formal quantitative and qualitative evaluation of medical center–based farmers’ markets is needed to further improve and translate theses markets to other medical settings. The RE-AIM (Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance) model22 proposes that at each step of developing, refining, and evaluating market-based interventions it is important to consider how well they are reaching the target population, their effectiveness in altering targeted outcomes, their adoption by other medical center settings, their consistency of implementing health initiatives, and factors contributing to their maintenance. On the basis of the RE-AIM model, the box on page e5 outlines some potential areas for the future evaluation of farmers’ markets on medical campuses to promote their continued refinement and translation to other settings.

RE-AIM Evaluation of Medical Center Farmers’ Markets to Enhance Their Effectiveness and Dissemination

| Evaluation Dimensions | Potential Measures |

| Reach | Demographic characteristics of market attendees |

| • Percentage of patrons who are patients, medical center employees, or community members | |

| • Number of repeat or regular customers | |

| • Number of customers registered with federal food stamp programs | |

| • Number of market-based partnerships with community organizations and nonprofits | |

| • Number of visits to farmers’ market Web site, Facebook page, and Twitter site | |

| Effectiveness | Patient or customer level |

| • Effects on diet, physical activity, and food purchases among regular market goers | |

| • Effect of market on perceived quality of life | |

| • Number of health screenings delivered in diverse health areas | |

| • Number of recipe cards or other items picked up by public while at market | |

| • Number of customers enrolling in health interventions promoted at marketFarmer level | |

| • Dollar value of sales | |

| • Generation of customer mailing lists | |

| • Degree of vendor or farmer brand recognition | |

| • Number of new partnerships between farmers and community organizations (e.g., contracting to supply products for local school or hospital cafeterias) | |

| Medical center level | |

| • Number of funded grants founded on farmers’ market | |

| • Number of papers published on farmers’ market and new knowledge obtained | |

| • Percentage of students reporting positive learning or training experiences at farmers’ market | |

| Community level | |

| • Trends in number of news articles about market and benefits of local or organic foods | |

| • Community advocacy for policies or services supporting access to local or organic foods | |

| Adoption | General engagement |

| • Number of medical center staff, students, or volunteers providing health services | |

| • Number of local vendors participating | |

| • Number of requests to market organizers to provide guidance for establishment of markets on other medical center campuses | |

| • Trends in growth of farmers’ markets on other academic medical center campuses | |

| Implementation | Consistency of programming, including |

| • Publicizing pedestrian-friendly ways to travel to market or free bicycle programs | |

| • Free health screenings from medical center volunteers | |

| • Hosting chef demonstrations on how to prepare healthy foods | |

| • Providing recipe cards to customers to suggest uses for featured market products | |

| • Offering samples of healthy foods (especially targeted to children) | |

| • Partnerships with medical center cafeteria to buy back leftover products from market | |

| • Recruitment for health interventions | |

| • Providing outreach and incentives to encourage walking | |

| • Weekly schedule of free wellness programming hosted by medical experts | |

| • Having local musicians play at market | |

| • Setting up tables and chairs for customers | |

| Maintenance | General engagement |

| • Volume of total customers and repeat customers over the long term | |

| • Long-term vendor commitment | |

| • Long-term staff, student, and volunteer commitment | |

| • Long-term institutional resources and funding support | |

| • Long-term partnerships with medical center staff and community organizations |

Although medical center farmers’ markets are growing in prevalence, the characteristics of market customers and barriers to market participation are not well understood. To expand the reach of medical center farmers’ markets, more research is needed to explore how demographic characteristics of patrons (e.g., age, socioeconomic status) and market features (e.g., location, product prices) interact to influence market participation. Future research should also explore whether shopping at farmers’ markets can increase the consumption of fresh produce or other healthy foods. This effect might occur directly, through the availability of more opportunities to purchase fresh produce, or indirectly, by promoting community norms, social networks (e.g., through Facebook), or policies that support healthy eating.23 Creative energy should also be invested in developing objective measures of the effects of market interventions such as date-stamped tracking of the types (e.g., fruits, baked goods) and quantity of customer purchases, the number of physician-dispensed “prescriptions” or vouchers redeemed at markets, and the amount of foot or bike traffic versus automobile traffic on routes leading to markets.24 Such measures could track the effectiveness of ongoing market programming and help refine the implementation of market initiatives to better address customer, farmer, medical center, community, and environmental health priorities.

Finally, there is a need for a better understanding of how market setup costs and institutional resources or support differ in rural and urban areas. In 2010, establishing and running the Farmers’ Market in Hershey cost approximately $8000 and required approximately 5 hours and 10 hours per week, respectively, for the market director and the market manager. Funds from a PSHMC philanthropic organization, service donations from PSHMC's marketing and public relations and printing departments, and market vendor fees covered these costs in part. The prevalence of farmers’ markets on medical campuses (Figure 1) suggests that the costs of establishing a market were feasible in other regions; however, future research should explore how regional variations in costs and resources can influence the adoption and maintenance of medical center farmers’ markets.

CONCLUSIONS

We have provided a qualitative description of how a seasonal, once-a-week, 80% local and organic farmers’ market was founded at PSHMC as well as suggestions for the ongoing evaluation and refinement of similar markets. The organizational challenges we encountered with the Farmers’ Market in Hershey are likely applicable to similar efforts on medical campuses in the United States, as are the unique opportunities to provide more complete, patient-centered care, and serve community wellness through diverse market programming. Farmers’ markets located on medical center campuses can add value to the market-going experience and contribute to greater wellness for employees, patients and their families, and local communities.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (grant R00 HL088017 to L. S. R.).

We would like to thank Pennsylvania State Hershey Medical Center, Pennsylvania State Humanities Department, the Hershey Center for Applied Research, the Hershey Trust, Hershey Entertainment and Resorts, and Pennsylvania State Hershey Association of Faculty and Friends for supporting the market. We also thank Karen Green, Wade Edris, Kathy Graham, Dan Shapiro, Kathy Morrison, Beth Bates, Judy Dillon, Deb Tregea, Erica Bates, Theresa White, Pam Campbell, and the numerous other volunteers who made the market possible.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.Brown A. Counting farmers markets. Geogr Rev. 2001;91(4):655–674. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. Number of Operating Farmers Markets. 2011. Available at: http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.do?template=TemplateS&leftNav=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&page=WFMFarmersMarketGrowth&description=Farmers%20Market%20Growth&acct=frmrdirmkt. Accessed August 16, 2011.

- 3.Kamphuis CB, Gisks K, de Bruijin GJ, Wendel-Vos W, Brug J, van Lenthe FJ. Environmental determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among adults: a systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(4):620–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markets F. United States Department of Agriculture. Farmers Markets and Local Food Marketing. 2010. Available at: http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/farmersmarkets. Accessed July 14, 2010.

- 5.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity. Solving the Problem of Childhood Obesity Within a Generation. 2010. Available at: http://www.letsmove.gov/pdf/TaskForce_on_Childhood_Obesity_May2010_FullReport.pdf. Accessed September 9, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Let's Move: America's Move to Raise a Healthier Generation of Kids. Available at: http://www.letsmove.gov. Accessed July 14, 2010.

- 7.Budget of the US Government. Fiscal Year 2011. Office of Management and Budget. Available at: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy11/pdf/budget.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2010.

- 8.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services. Obama Administration Details Healthy Food Financing Initiative [press release]. February 19, 2010. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2010pres/02/20100219a.html. Accessed September 9, 2010.

- 10.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, and American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Available at: http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/medical_home/approve_jp.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- 11.Kaiser Permanente. Medical Center and… Grocery Store? Available at: https://members.kaiserpermanente.org/redirects/farmersmarkets. Accessed February 25, 2011.

- 12.McCormack LA, Laska MA, Larson NI, Story M. Review of the nutritional implications of farmers’ markets and community gardens: a call for evaluation and research efforts. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(3):399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glanz K, Yaroch AL. Strategies for increasing fruit and vegetable intake in grocery stores and communities: policy, pricing, and environmental change. Prev Med. 2004;39(suppl 2):S75–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ni Mhurchu C, Blakely T, Jiang Y, Eyles HC, Rodgers A. Effects of price discounts and tailored nutrition education on supermarket purchases: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(3):736–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reger B, Wootan MG, Booth-Butterfield S. A comparison of different approaches to promote community-wide dietary change. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(4):271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer N. Eat an apple (doctor's orders). New York Times. August 12, 2010. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/13/business/13veggies.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=massachusetts+farmers+market+prescriptions&st=cse. Accessed September 7, 2010.

- 17.Racine EF, Smith VA, Laditka SB. Farmers’ market use among African-American women participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(3):441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kropf ML, Holben DH, Holcomb JP, Anderson H. Food security status and produce intake and behaviors of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program participants. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1903–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ver Ploeg M, Breneman V, Farrigan T, et al. Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food—Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences: Report to Congress. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/AP/AP036. Accessed September 7, 2010. Administrative Publication No. AP-036.

- 20.Shenkin JD, Jacobson MF. Using the food stamp program and other methods to promote healthy diets for low-income consumers. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1562–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanford Hospital & Clinics. New on Our Menu. Available at: http://stanfordhospital.org/farmfresh. Accessed June 30, 2010.

- 22.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hovell MF, Wahlgren DR, Adams M. The logical and empirical basis for the behavioral ecological model. : DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, Emerging Theories and Models in Health Promotion Research and Practice: Strategies for Enhancing Public Health. 2nd ed San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009:415–450. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coley D, Howard M, Winter M. Local food, food miles and carbon emissions: a comparison of farm shop and mass distribution approaches. Food Policy. 2009;34(2):150–155. [Google Scholar]