The opportunity to more effectively address health disparities and work toward health equity in the United States has never been greater. There has been growth not just in our understanding of the prevalence of health disparities but also in factors that influence them, a growing constituency for health equity, and important investments in programs focused on reducing health disparities and that contribute to improved conditions for better health.1–3 There also has been growing acceptance that changes needed to achieve health equity in the United States can take place only with the cooperative effort of individuals at all levels within the public, nonprofit, and private sectors.4,5 Health equity has been defined as attainment of the highest level of health for all people. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and health care disparities.6

With this knowledge and increased potential for contributing to a healthier America, the Office of Minority Health, US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), brought together thousands of stakeholders to develop the National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities (NPA). The NPA-related processes identified common interests through a sequence of activities that included regional meetings for communities and other stakeholders, a national public comment period, and numerous levels of review, analysis, and content refinement by a range of experts. The guiding principles established for the NPA were based on values that were inclusive and elevated the importance of community engagement; emphasizing the necessity of being culturally and linguistically competent to serve all communities; and requiring nondiscrimination in actions, services, leadership, and partnerships. The NPA takes a broad view of health disparity populations including individuals who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial/ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.

The NPA and other efforts to unite around health equity have been strengthened by the historic passage of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PL 111–148),1 as amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act (PL 111–152), a law that among other provisions increases access to quality health care for millions of Americans, makes improvements in prevention and coordination of care, expands the health care workforce, and improves the diversity and cultural competency of health care professionals. Also of significance is congressional language that encouraged the development of a “National Strategy to Eliminate Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care” to be implemented and monitored in partnership with State and local governments, communities, and the private sector.7

DRIVING COLLECTIVE ACTION

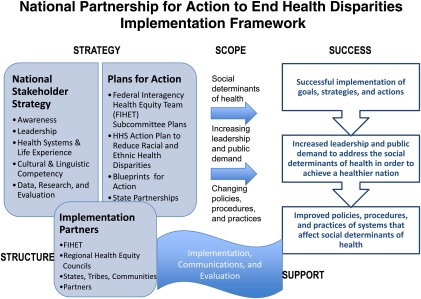

The factors that contribute to poorer health outcomes for affected populations are complex and cannot be addressed by individuals and organizations acting independently. Rather, addressing disparities in health will take deliberate and collaborative actions by individuals and organizations across all sectors (e.g., environment, education, employment, housing). This view was incorporated not only into the development of the NPA, but also into its implementation approach, which includes the following five factors (Figure 1):

Strategy. Advancing an overarching stakeholder approach and developing key documents to guide collective action.

Scope. Applying a social determinant of health approach to efforts across all sectors and levels to drive holistic and inclusive change.

Structure. Involving multisectoral partners and strengthening the structure to implement the strategy.

Support. Providing technical assistance on implementation, communication, and evaluation to enhance and sustain national implementation.

Success. Assessing immediate and long-term outcomes to demonstrate and measure success.

FIGURE 1.

National partnership for action to end health disparities implementation framework.

Note. FIHET = Federal Interagency Health Equity Team.

Strategy

In 2011, HHS concurrently released two key documents that together promote collaborations among communities, states, tribes, nonprofit and private sectors, and other stakeholders to more effectively reduce health disparities. The HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities builds on the Affordable Care Act through goals that seek to transform health care; strengthen the health and human services workforce; advance health safety and wellness; advance scientific knowledge and innovation; and increase the efficiency, transparency, and accountability of HHS programs for reducing health and health care disparities.8 Key components of the HHS Action Plan include its focus on assessing policies and programs that impact health disparities, using outcome assessments to inform department-wide decision making, driving cohesive action across HHS agencies, evaluating departmental progress, and holding HHS leaders accountable for progress.

The second document is the National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity, the principal product of the NPA, which provides a roadmap for collective action around five goals and 20 community-driven strategies. The goals include

increasing awareness of the significance of health disparities, their impact on the nation and the actions necessary to improve health outcomes for racial, ethnic, and underserved populations;

strengthening and broadening leadership for addressing health disparities at all levels;

improving health and health care outcomes for racial, ethnic, and underserved populations;

improving cultural and linguistic competency and the diversity of the health-related workforce; and

improving data availability and coordination, utilization, and diffusion of research and evaluation outcomes.

Many of the strategies outlined in the National Stakeholder Strategy have been highlighted in previous studies as being key to disparities reduction.9,10

Structure

The NPA implementation structure includes the Federal Interagency Health Equity Team (FIHET), partners (which include states, tribes, and communities), and Health Equity Councils. The FIHET was established to guide the NPA and consists of representatives from 12 federal departments and agencies (Agriculture, Army, Commerce, Education, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Justice, Labor, Transportation, Veterans Affairs, Environmental Protection Agency, and Consumer Product Safety Commission). The FIHET is specifically working to (1) identify opportunities for federal collaboration, partnership, coordination, and action on efforts that are relevant to the NPA; (2) provide leadership and guidance for national, regional, state, and local efforts that address health equity; and (3) leverage opportunities for integrating health disparities into policies, practices, and initiatives.

Partnership activities engaged the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Conference of State Legislatures, National Business Group on Health, National Association of State Offices of Minority Health, and the National Rural Health Association. Examples of partner activities include state offices of minority health efforts to

engage communities in the NPA through local meetings,

develop strategic partnerships,

mobilize networks,

improve awareness and communications about health disparities through different media outlets, and

lead states’ efforts in updating health disparity or health equity plans so that they align with the NPA goals.

Numerous NPA partnerships have also been established with other organizations across the country.

A more recent structural component to the NPA implementation is the establishment of 10 Regional Health Equity Councils that represent groups of states nationwide. The launch of the councils began in August 2011, and their membership includes individuals from the public, nonprofit, and private sectors who represent communities experiencing health disparities; state and local government agencies; tribes and tribal organizations; health care providers and systems; health plans; businesses; academic and research institutions; foundations; and other organizations who focus on specific determinants of health (e.g., environmental justice, housing, transportation, education). Each council will address health disparity improvement actions for their geographic areas by helping to harmonize multisectoral health disparity actions in their region; infuse common NPA goals and strategies into policies and practices; provide lateral, cross-boundary leadership; serve as catalysts, subject matter experts, and innovators; and leverage health disparity investments.

Support

Implementation of common goals will take time and require support. Technical assistance is available to improve capacity, communicate about health disparities, and evaluate collaborative efforts. Methods for providing technical assistance include toolkits (existing and new as needed), webinars, portals, and written products (e.g., on topics that include how to access state data for key social determinants; how to use data to inform strategies for ongoing monitoring and learning; developing measures for data collection; facilitating local conversations about health disparities).

Success

An evaluation strategy has been developed to assess immediate and long-term actions of the NPA, including collaborative actions. Measures of success related to the FIHET, NPA partners, and state offices of minority health focus, for example, on whether their actions were productive and effective, contributed to improved awareness, aligned with national, regional, state, tribal, and local health disparity efforts, were both multisector and multilevel types of actions, and met goals.

CONCLUSIONS

The development phase of the NPA confirmed that a broad range of individuals and organizations could agree on a common set of goals and strategies. Thousands of individuals participated in community, regional, and national meetings and provided input on the goals and strategies of the NPA and National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity through these meetings and through a national comment period. Although early in its implementation, the NPA has already made a difference in the way partners framed their work both individually and collectively. Now partners are beginning to use NPA goals, a marked progress that ultimately translates into positive opportunities for communities. There also have been early indications that diverse individuals and organizations are ready to own and collectively drive NPA goals and strategies that connect to their work at the state and local levels. Nine of the ten Regional Health Equity Councils were launched and coalesced quickly around common NPA goals. The councils expressed a deep sense of urgency to collectively act on common goals and the important confluence of current opportunities to advance national efforts.

Collective action to end health disparities is possible if individuals and organizations, those with a vested interest, are engaged in the work as equal partners. The NPA offers a forum for sharing ideas and resources, an opportunity to partner, and a collaborative approach to problem solving. ▪

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Report on minority health activities as required by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, PL 111–148. March 23, 2011. Available at: http://www.healthcare.gov. Accessed September 23, 2011

- 2.Dankwa-Mullan I, Rhee K, Stoff D, et al. Moving toward paradigm-shifting research in health disparities through translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary approaches. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S12–S18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smedley BD. Moving beyond access: achieving equity in state health care reform. Health Aff(Millwood). 2008;27(2):447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sondik EJ, Huang DT, Klein RJ, Satcher D. Progress toward the Healthy People 2010 goals and objectives. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services National stakeholder strategy for achieving health equity. April 8, 2011. Available at: http://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/templates/content.aspx?lvl=1&lvlid=33&ID=286. Accessed September 23, 2011

- 7.US Congress Report of the committee on appropriations. 111th Congress. 1st Session. Report 111-220. July 22, 2009. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CRPT-111hrpt220/pdf/CRPT-111hrpt220.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2011

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services HHS action plan to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. April 8, 2011. Available at: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/templates/content.aspx?lvl=1&lvlid=33&ID=285. Accessed September 23, 2011

- 9.Doonan MT, Tull KR. Health care reform in Massachusetts: implementation of coverage expansions and a health insurance mandate. Milbank Q. 2010;88(1):54–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IOM Subcommittee on Standardized Collection of Race/Ethnicity Data for Healthcare Quality. Board on Health Care Services Ulmer C, McFadden B, Nerenz DR, Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]