Abstract

Cryptococcus gattii is a known emerging infectious disease pathogen predominantly in the Pacific Northwest USA and British Columbia, Canada. We report a case of an immunocompetent adolescent from New England who had severe pulmonary and central nervous system infection caused by the VGI genotype of C. gattii.

Keywords: Cryptococcus gattii, cryptococcal meningitis, genotype VGI, New England

Introduction

Cryptococcus gattii is an emerging infectious disease occurring predominantly in the Pacific Northwest United States that can infect both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent hosts[1, 2]. Seventy human cases of C. gattii have been reported to the CDC in this region from 2004 to 2010, and among the 45 cases with known outcomes the mortality rate was approximately 20%[3]. Movement of this pathogen into temperate climates suggests a broadening of its geographic range beyond previously-associated tropical and subtropical regions. There are four C. gattii molecular types found worldwide (VGI–VGIV). Types VGI and VGII are usually associated with infections of immunocompetent hosts[1], and types VGIII and VGIV are often associated with infections in immunocompromised patients. Recent reports suggest expansion of molecular type VGII (specifically subtypes VGIIa and VGIIc) into the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Vancouver, Canada, and type VGI may be expanding in geographic scope to California and infecting an increasing diversity of mammalian hosts[1]. This report describes an immunocompetent adolescent from New England with pulmonary and CNS C. gattii infection of the VGI subtype with no recent travel to an endemic area, suggesting local acquisition may have occurred.

Case

A 15-year-old previously healthy female from Southern New England presented in 2009 to Rhode Island Hospital with two months of shortness of breath and a focal seizure. Before admission, she had been treated for one month for progressive dyspnea and wheezing symptoms presumed to be new-onset asthma with montelukast, albuterol inhalers, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and a 5-day course of prednisone. The patient had not previously been treated for asthma and had never taken corticosteroids prior to onset of her respiratory symptoms. No imaging had been performed. She also reported intermittent fevers, cough, and headaches during the preceding two months. Previous travel included a ski vacation to Colorado and a winter vacation to Quebec one year before presentation with no symptoms before or after those trips. Two years prior to presentation, the patient traveled to central Florida and Maine, and almost 4 years before presentation, the patient took a Caribbean cruise which included a visit to caves and jungles in Belize and trips to multiple islands, including Haiti. She performed well in school, participated in team sports, denied use of tobacco, alcohol or illicit drugs and denied being sexually active. Her vaccinations were current for her age, including seasonal influenza.

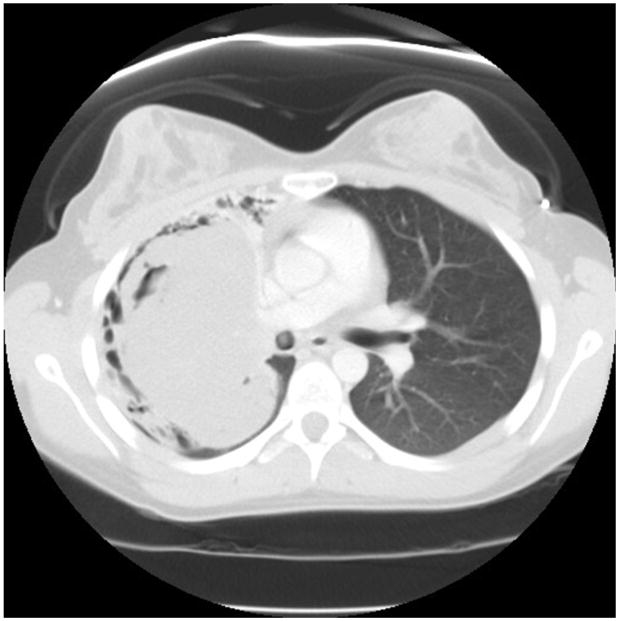

Examination at hospital admission revealed her to be tachypneic, thin, fully oriented and in no apparent distress. Her lungs had diffuse wheezes. The remainder of the examination, including neurologic assessment was unremarkable. Initial laboratory investigation revealed a white blood cell count of 14.8 ×109/L, hemoglobin 139 g/L, and platelets 517 × 109/L. In the course of her workup for a new partial seizure, an EEG demonstrated positive sharp transient waves in the right occipital region. A chest CT revealed an 11×7×9 cm heterogeneous solid and cystic pulmonary mass extending into the right mainstem bronchus, obliterating the right upper lobe bronchus, which was also visualized by bronchoscopy (Figure 1 and Supplemental Digital Content 1 (figure)). Transbronchial biopsy revealed an inflammatory mass containing encapsulated yeasts. The biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage later grew Cryptococcus sp. A brain MRI with gadolinium showed a 3mm focus of abnormal rim enhancement in the right caudate without mass effect. A lumbar puncture (LP) had an elevated opening pressure at 28cm H2O and 71 nucleated cells, 94% lymphocytes. ACSF calcofluor stain demonstrated yeast suggestive of Cryptococcus and the culture grew Cryptococcus, later identified as C. gattii by demonstration of resistance to canavanine and utilization of glycine on L-canavanine, glycine, 2-bromothymol blue (CGB) agar, which differentiates C. gattii from C. neoformans[4]. CSF cryptococcal antigen titer by latex agglutination (Immuno-Mycologics, Inc., Norman, OK) was 1:128 (see Table). A transthoracic echocardiogram was normal.

Figure 1.

CT image showing lung mass in the right upper and middle lobes of the lung with invasion into the right mainstem bronchus

Table 1.

CSF findings during induction and consolidation therapy

| Sample date | 12/28/09 | 12/31/09 | 1/4/10 | 1/5/10 | 1/13/10 | 2/2/10 | 3/4/10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC 109/ml | 71 | 84 | 54 | 52 | 6 | 10 | 12 |

| RBC 109/ml | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Neut % | 1 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Lymph % | 94 | 80 | 66 | 76 | 85 | 97 | 90 |

| Mono % | 1 | 10 | 25 | 12 | 15 | 2 | 10 |

|

| |||||||

| Culture date | 12/30/09 | 12/31/09 | 1/1/10 | 1/4/10 | 1/5/10 | 1/13/10 | 3/4/10 |

|

| |||||||

| Calcofluor stain | + | + | + | + | + | — | — |

| Culture | 2+ C. gattii | 1+ C. gattii | 1+ C. gattii | — | — | — | — |

With the exception of a low absolute CD56 count (0.036 K/μL, normal 0.1–0.4 K/μL), the patient had no evidence of immunologic or anatomic abnormalities. HIV ELISA testing was negative; and immunoglobulin values, IgG subsets, dihydrorhodamine (DHR), antigen stimulation, and mitogen proliferation testing were within normal limits.

She was treated with liposomal amphotericin B and flucytosine and required serial LPs for symptomatic relief of headache and blurred vision. Flucytosine was discontinued after 2 weeks. At the end of treatment week 1, the patient underwent a right upper lobe lobectomy, partial lobectomy of the right middle lobe, and repair of the right mainstem bronchus. Resected tissue demonstrated obliteration of normal anatomy by a large fungal mass. Histology of the resected tissue demonstrated bronchocentric granulomatous inflammation and organizing pneumonia with a 15cm dominant nodule composed of yeast forms.

Repeat brain MRI two weeks after initial therapy showed increasing number of enhancing lesions. Additionally there was new leptomeningeal enhancement suspicious for disease progression (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2). An ophthalmologist confirmed grade I–II optic disc edema. Clinically the patient had improved and, based on review of the clinical and radiologic data by national experts and neuroradiologists, the imaging findings were thought to be consistent with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Due to these findings, flucytosine was reinitiated for another two weeks. Serial LPs with CSF cultures demonstrated gradual improvement (see Table). An MRI at 10 weeks revealed increased leptomeningeal enhancement with stable size of all lesions. Another MRI scan 5 months later demonstrated diminished meningeal enhancement and reduced size of all observed CNS lesions.

After 8 weeks of liposomal amphotericin B and 4 total weeks of flucytosine, the patient began consolidation therapy with oral fluconazole 800mg daily for 8 weeks and continued fluconazole, 400mg daily for an anticipated 12–18 month course. At present, the patient is asymptomatic and functioning well 1 year after initiation of antifungal therapy.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) [5] at eight unlinked genomic loci revealed that the isolate was molecular type VGI, a common genotype observed in global isolates from Australia, Mexico, India, and Europe[6] (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3). This isolate is clearly distinct from the VGII outbreak genotypes and also distict from a VGI genotype observed in a man from North Calolina who had travel-exposure in California[6].

Discussion

Cryptococcus gattii has emerged as an important cause of infection in Vancouver, British Columbia, and later in the Pacific Northwestern USA[1, 3]. Our case is significant because it occurred in the Northeastern USA in a patient who had not traveled to a tropical region in >3 years before hospital admission for C. gattii infection. This case differs from the Pacific Northwestern outbreak and involves a VGI genotype endemic to tropical and subtropical climates world-wide[1, 7]. Interestingly, C. gattii has not yet been found in the Eastern USA[6], and to our knowledge, no studies have reported isolation of C. gattii from the environment in New England.

Cryptococcus gattii more often causes CNS disease, including cryptococcomas[8, 9]. As such, the 2010 Infectious Disease Society of America Guidelines recommends close CNS monitoring in C. gattii cases although treatment regimens remain the same as for C. neoformans[10]. Definitive length for induction therapy in cryptococcal meningitis in non-HIV- infected patients is uncertain and, at present, recommendations are to treat C. gattii the same as C. neoformans, though conclusive studies to support this recommendation have not been conducted.

Additionally, C. gattii tends to affect immunocompetent patients more frequently than C. neoformans[11]. Although our patient appears to be immunocompetent, the number of CD56+ natural killer cells was decreased and natural killer cells play a role in combating Cryptococcus infection [12, 13]. Our patient appeared to develop IRIS which has been reported in immunocompetent hosts with severe cryptococcal infection, sometimes requiring aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy to ameliorate neurologic symptoms[10, 14]. Finally, it is unclear if our patient developed C. gattii from a source in New England or reactivation from travel-related and latent infection. However, few studies demonstrate reactivation disease caused by C. gattii, and these are limited to HIV-positive patients[15]. Further studies are warranted to determine if C. gattii is endemic in the Northeastern USA.

Supplementary Material

Bronchoscopy image showing a large nearly obstructing lesion just at the takeoff of the right upper lobe bronchus

MRI scan demonstrating an enhancing lesion of the midbrain tegmentum shortly after completion of induction therapy. Multiple similar lesions were found in the right caudate head, left cerebellar hemisphere, and adjacent to the left lateral ventricle

Table of MLST genotype analysis of C. gattii isolated from our patient

Acknowledgments

Genotyping was performed in Dr. Heitman’s lab which is supported by NIH grant NIH/NIAID R01 AI39115. The following individuals provided valuable input into the development of this manuscript: Nicole E. Alexander, MD; Leonard A. Mermel, DO; Terrance Healey, MD; and Carolynn M. Debenedectis, MD

References

- 1.Byrnes EJ, III, et al. Emergence and pathogenicity of highly virulent Cryptococcus gattii genotypes in the northwest United States. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6(4):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidd SE, et al. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada) PNAS. 2004;101(49):17258–17263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402981101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Emergence of Cryptococcus gattii-- Pacific Northwest 2004–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(28):865–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwon-Chung KJ, Polacheck I, Bennett JE. Improved diagnostic medium for separation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (serotypes A and D) and Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii (serotypes B and C) J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15(3):535–537. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.3.535-537.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maiden MC, et al. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(6):3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrnes EJ, 3rd, et al. PLoS One [serial online] 6. Vol. 4. Public Library of Science; San Francisco, CA: 2009. [Accessed April 12, 2011]. First reported case of Cryptococcus gattii in the Southeastern USA: implications for travel-associated acquisition of an emerging pathogen; p. e5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. High prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in tropical and subtropical regions. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1984;257(2):213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speed BD, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28–34. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell D, Sorrell TC, Allworth AM. Cryptococcal disease of the CNS in immunocompetent hosts: influence of cryptococcal variety on clinical manifestations and outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:611–616. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perfect JR, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(3):291–322. doi: 10.1086/649858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartlett KH, Kidd SE, Kronstad JW. The emergence of Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2008;10(1):58–65. doi: 10.1007/s11908-008-0011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitz SM, Dupont MP, Smail EH. Direct activity of human T lymphocytes and natural killer cells against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1994;62(1):194–202. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.194-202.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brouwer AE, et al. Journal of Infection [serial online] Vol. 54. Elsvier, Inc; Waltham, MA: 2007. [Accessed April 12, 2011]. Immune dysfunction in HIV-seronegative, Cryptococcus gattii meningitis; pp. e165–e168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecevit IZ, et al. The poor prognosis of central nervous system cryptococcosis among nonimmunosuppressed patients: a call for better disease recognition and evaluation of adjuncts to antifungal therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(10):1443–1447. doi: 10.1086/503570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dromer F, Ronin O, Dupont B. Isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from an Asian patient in France: evidence for dormant infection in healthy subjects. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30(5):395–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Bronchoscopy image showing a large nearly obstructing lesion just at the takeoff of the right upper lobe bronchus

MRI scan demonstrating an enhancing lesion of the midbrain tegmentum shortly after completion of induction therapy. Multiple similar lesions were found in the right caudate head, left cerebellar hemisphere, and adjacent to the left lateral ventricle

Table of MLST genotype analysis of C. gattii isolated from our patient