Despite the availability of many diagnostic and therapeutic options to evaluate and treat patients with liver diseases, optimizing these approaches remains a challenge. Endoscopic ultrasonography has proven to be useful in the investigation of gastrointestinal diseases, but has also emerged as a useful modality in the assessment of patients with hepatobiliary diseases. Coupled with other established techniques, such as Doppler imaging and fine-needle aspiration, endoscopic ultrasonography has shown vast potential in both animal models and human studies. This article reviews the use of endoscopic ultrasonography in the investigation, diagnosis and management of patients with portal hypertension, focal liver lesions and biliary tract lesions. Although its availability is currently limited to large tertiary centres, its use is expected to increase once better access to equipment and training is established.

Keywords: Doppler technique, Endoscopic ultrasonography, Esogastric varices, Fine-needle aspiration, Portal hypertension

Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is used to evaluate patients with hepatobiliary diseases. The technique is useful for the diagnosis of esogastric varices in selected cases of portal hypertension, and to evaluate the pathogenic role and prognostic value of the collateral circulation in patients with this condition. When coupled with the Doppler technique, EUS can be used to guide injection sclerotherapy and to verify the obliteration of varices (particularly fundal varices) after endoscopic treatment. Hemodynamic changes induced in the collateral circulation by vasoactive drugs can also be measured with Doppler-EUS. Fine-needle aspiration under EUS guidance is useful in the diagnosis of focal liver lesions and perihepatic adenopathy, and in the evaluation of biliary tract diseases. New indications can be developed in the future after adequate experimental validation.

Abstract

L’échographie per endoscopique (EE) est un nouvel outil utilisé pour évaluer les patients ayant une suspicion de maladie hépato-biliaire. Elle est utile pour le diagnostic des varices oeso-gastriques dans certains cas particuliers d’hypertension portale; elle permet aussi d’étudier la circulation collatérale, sa signification physiopathologique et sa valeur pronostique. L’association de l’EE avec la technique Doppler permet de guider la sclérothérapie de varices per endoscopique et également de vérifier l’oblitération des varices après traitement (particulièrement les varices fundiques). Il est également possible de mesurer les effets hémodynamiques de médicaments vaso-actifs sur la circulation collatérale. La cytologie à l’aiguille fine peut être réalisée grâce à un guidage échoendoscopique au niveau des lésions hépatiques focales ou d’adénopathies suspectes ainsi que de lésions de l’arbre biliaire. Il est probable que de nouvelles applications vont émerger après une validation expérimentale adéquate.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has led to many changes in the investigation of gastrointestinal diseases. The assessment of proximal submucosal gastrointestinal lesions, and the evaluation of abnormal lymph nodes, pancreatic lesions and the distal biliary tract, are well-recognized clinical indications.

Many diagnostic options to evaluate patients with chronic liver disease are available. However, the optimal diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to liver diseases still present many challenges. There is evidence to suggest that EUS alone or combined with Doppler or fine-needle aspiration (FNA) represent a significant advance in the evaluation and treatment of these patients.

The present article reviews the use of EUS in the diagnosis and management of portal hypertension (PHT), focal liver lesions and biliary tract lesions. A thorough MEDLINE search using the terms “endosonography”, “cirrhosis”, “hepatology”, “portal hypertension” and “liver lesions” was performed to retrieve articles published between January 1997 and December 2009.

EUS IN PHT

This topic has been addressed in several recently published reviews (1–4).

Visualization of portal collaterals and pathophysiological significance

EUS enables the visualization of esophagogastric varices and other venous collaterals in patients with PHT, and can be useful to assess the patency of the portal venous system. Due to their size, the diagnostic yield of the first echoendoscopes was limited because they compressed esophageal varices (EV). Newer echoendoscopes have a diagnostic accuracy comparable with standard esophagogastroduodenoscopes (EGDs) as reported by Lee et al (5), who obtained respective sensitivity and specificity values, and positive predictive values and negative predictive values of 96.4%, 95.8%, 96.4% and 95.8% for EV, and 43.8%, 94.4%, 77.8% and 79.1% for the diagnosis of gastric varices (GV) in a group of patients with cirrhosis not known to have gastroesophageal varices (GEV). A good correlation between the two modalities was obtained for EV, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.855. Kane et al (6) demonstrated a correlation between the grading of EV using a transnasal endosonographic high-resolution (20 MHz) probe and EGD (kappa coefficient = 0.63). Smaller varices were detected at an earlier stage.

In addition, EUS combined with colour Doppler imaging enables better appreciation of gastric submucosal lesions than EGDs before proceeding to the biopsy of potential GV (Figure 1). There is currently no established classification of GEV assessed by EUS. However, this technique enables the measurement of varices, as opposed to EGD, in which classifications rely on subjective evaluation.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic image of gastric varices (GV)

The usefulness of EUS was also demonstrated in a study that evaluated the so-called hematocystic spots on EV in patients with liver cirrhosis (7). The high-resolution EUS probe demonstrated that these spots are focal weaknesses in the variceal wall producing an aneurysm-like projection. Follow-up of these patients revealed that the presence of hematocystic spots is associated with a high risk for a first bleeding and subsequent rebleeding.

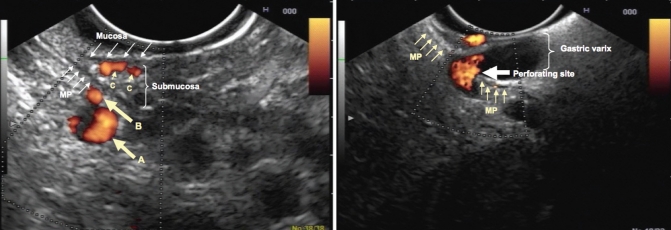

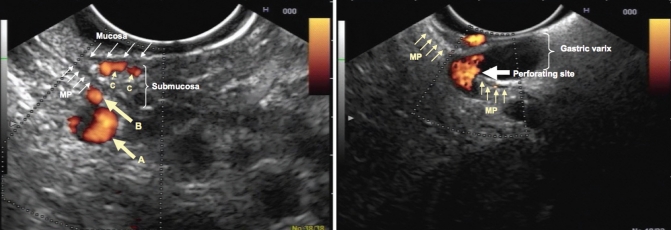

EUS enables visualization of other portosystemic collaterals such as periesophageal collateral veins (peri-ECV), paraesophageal collateral veins (para-ECV) and perforating veins (PfV) (Figure 2). EUS also helped to understand the role of portosystemic collaterals in the formation of GEV. Peri-ECV are located in the connecting tissue surrounding the esophagus, adjacent to the muscularis propria. Para-ECV run outside of the esophageal wall. PfV connect extramural collateral veins to the submucosal varices. Percutaneous transhepatic portography also permits visualization of these collaterals, but it cannot establish their precise location in relation to the esophageal wall, and is significantly more invasive than an endoscopic procedure.

Figure 2.

Left panel Perigastric portal hypertension. Endoscopic ultrasound with Doppler array showing a paragastric collateral vein (A), perigastric collateral vein (B) and gastric varices (C). The gastric varices are located in the submucosa, which corresponds to the hyperechoic layer surrounded by adjacent hypoechoic layers (mucosa and muscularis propria [MP]). Right panel Perforating vein. Endoscopic ultrasound with Doppler array showing a large perigastric collateral vein perforating (thick arrow) the MP of the gastric wall (thin arrows), leading to a significant submucosal varix

The validity of assessment of the collateral network by EUS was evaluated in a comparison with autopsy findings in four patients with EV who underwent endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) followed by EUS (8). A good correlation between EUS and autopsy results was demonstrated. In 22 patients with untreated EV, EUS of the collateral network was studied: all patients had collateral veins adjacent to or outside of the esophagus, compared with none in five healthy controls. Peri-ECV were significantly larger in patients with the largest varices (F3 [as described by the Japanese Society for Portal Hypertension]). The mean number and diameter of PfV connecting peri-ECV and EV increased when the F factor was higher. There was no correlation between para-ECV and their PfV and the size of EV as assessed by a EGD (9).

The prognostic value of para-ECV was studied by Irisawa et al (10). After EIS, esophageal varices recurred in patients with para-ECV and PfV, but not in those without PfV. Therefore, para-ECV and PfV probably represent an important collateral pathway in PHT, and their presence is associated with an increased risk of variceal recurrence.

EUS was used to search for the presence of a gastrorenal shunt in patients with gastric fundal varices (11). A kappa index of 0.9 between EUS and computed tomography (CT) imaging was obtained, illustrating a good diagnostic accuracy and suggesting that EUS could help select patients for balloon retrograde transvenous obliteration (12).

EUS also enables the detection of rectal varices in a greater proportion of cirrhotic patients than endoscopy (13). However, its role in the investigation of lower digestive hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients remains undefined.

EUS has proven to be helpful in the evaluation of the patency of the portal venous system (Figure 3) when combined with the Doppler technique. Lai and Brugge (14) demonstrated an overall diagnostic accuracy of 0.89 for EUS for portal venous system thrombosis in a retrospective study of 45 patients. In addition, EUS was shown to be more reliable than transabdominal Doppler ultrasonography in assessing the patency of the portal venous system including the splenic vein – a key vessel in the pathogenesis of isolated GV (15).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of portal vein patency. Endoscopic ultrasound with Doppler array showing a subtotal portal vein (PV) obstruction, with minimal peripheral intravascular flow (thin arrows). There are concomitant periduodenal collateral veins (thick arrows)

EUS enables good visualization of the azygos vein – an important collateral pathway in PHT. Azygos blood flow (AzBF) measurement has been validated recently using a flow phantom (16); it has been used as an index of variceal blood flow at baseline and under the influence of different vasoactive drugs. Kassem et al (17) studied the influence of EUS on azygos vein circulation, and described significant increases in vessel diameter, maximal velocity and blood flow volume index in patients with PHT. The validity of colour Doppler imaging for the determination of AzBF was demonstrated by another study (18) that compared it with the thermodilution method (correlation coefficient = 0.875). Doppler EUS was then used to evaluate the acute hemodynamic effects of the infusion of the vasoactive agents somatostatin and octreotide on portal circulation. Results showed an initial decrease in AzBF after infusion of both substances (within 10 min) for both when compared with placebo. This was followed by a rebound increase in AzBF after 60 min of somatostatin infusion and a return to baseline values for octreotide (18).

In an effort to better predict the risk of variceal bleeding, endoscopic EV pressure recording using a pneumatic balloon has been proposed. However, this technique yields important variability with time. Therefore, Pontes et al (19) proposed using endoscopic power Doppler imaging to directly monitor variceal pressure during balloon compression. Successful determination of variceal pressure was achieved in 26 of 28 patients with liver cirrhosis. Their results were then compared with conventional hepatic venous pressure gradient HVPG measurement in 16 of those patients. Variceal pressure correlated significantly with HVPG (r=0.64, P<0.001).

Finally, it has been shown in animal studies that the portal venous system can be catheterized under EUS guidance (20,21), and that an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt can be created successfully (22).

EUS IN THE CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF PHT

The evaluation of GEV and their collaterals by EUS has potential clinical implications. Assessment of the collateral venous network around the esophagus and of its tributary veins by EUS helps predict the recurrence of varices after endoscopic eradication. Irisawa et al (23) demonstrated that EV recurrence was associated with the presence of large peri-ECV and with the number and size of PfV in a study involving 38 cirrhotic patients. Para-ECV were not associated with recurrence. Interestingly, it was noted that these findings on EUS preceded the recurrence of EV by three to four months. Konishi et al (24) also emphasized the significance of PfV by studying submucosal cardial vessels before and after eradication of EV by endoscopic band ligation in 30 patients at high risk for bleeding. The presence of severe type PfV was strongly associated with an early (three months) relapse of varices (25). Sato et al (25) demonstrated that the presence of patent PfV before and after EIS, and the presence of cardiac intramural veins were significantly predictive of early recurrence of EV. A similar study evaluating the number of cardiac vessels by EUS at the time of combined endoscopic therapy (26) showed that the number of these vessels was predictive of variceal relapse.

Studies have also focused on the left gastric vein (LGV), which is the main feeder of EV. The LGV divides into an anterior branch, flowing into EV, and a posterior branch that connects to the azygos and hemiazygos system. Kuramochi et al (27) performed EUS with colour Doppler imaging before and after endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) in 68 patients with medium to large EV. Patients were classified as high-risk for relapse if they had a dominant LGV with high-velocity blood flow in the anterior branch. Follow-up showed that the incidence of EV relapse was higher in these patients.

Sato et al (25) demonstrated that the presence of inflowing PfV before and after EIS, and the presence of cardiac intramural veins were significantly predictive of early recurrence of EV. As a consequence, Lahoti et al (28) proposed a new approach to eradicate EV. EIS was successfully performed in five cirrhotic patients under EUS guidance. Importantly, feeder collateral vessels were injected until blood flow was undetectable. The mean number of endoscopic sessions was 2.2, with no recurrence of bleeding, although esophageal stricture formation was observed in one patient.

A randomized controlled study (29) compared conventional EIS with EUS-guided EIS in 50 patients with liver cirrhosis and EV. Once again, the target vessels were the PfV supplying the submucosal varices. After at least one year of follow-up for most patients, variceal recurrence occurred in four patients in the EIS group and in two patients in the EUS group (P=0.321). Collateral vessels were noted to have recurred in those two patients. Significant bleeding was not reported.

EUS was used to guide the injection of cyanoacrylate in a small study involving five patients with GV (30); eradication was successful and no complications were reported. In addition, EUS can be used to evaluate the obliteration of GV after histoacryl injection.

INVESTIGATION OF HEPATIC AND BILIARY TRACT LESIONS

FNA is one of the most frequent applications of EUS in the investigation of upper gastrointestinal lesions. Its use in lesions of the liver and biliary tract has been described in many articles. Hilar as well as right and left lobe lesions can usually be sampled.

Cytology/biopsy of liver lesions is a common indication for EUS-FNA to diagnose primary or metastatic malignancy. Single-centre series reported that EUS-FNA is similar to CT-FNA in terms of diagnostic accuracy and management of liver lesions (31).

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is an important cause of mortality among cirrhotic patients. The importance of an early diagnosis to increase the chances of curative therapy has been well established. Current screening strategies include alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level measurement and abdominal ultrasound (US) twice a year. The role of FNA under endoscopic guidance has been reviewed recently (32). A single-centre prospective study compared EUS with abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT and US for the detection of HCC in a small series of patients judged to be at high risk based on an elevated AFP level (>8.1 ng/mL) (33). The diagnostic accuracy of US, CT, MRI and EUS/EUS-FNA were 38%, 69%, 92% and 94%, respectively. EUS had a clear advantage over CT for the detection of small lesions; the authors reported that they were able to perform multiple aspirations in the right liver lobe. A diagnostic algorithm was proposed in which EUS is used for high-risk patients with negative or inconclusive CT, or poorly accessible lesions.

Awad et al (34) used EUS for preoperative evaluation before resection of HCC or metastatic lesions in 14 patients, which had a clear influence on management. EUS had better sensitivity than CT for detecting liver lesions as small as 0.3 cm in size. It also helped differentiate metastasis from hemangioma in two patients.

A single-centre series of 77 patients evaluated with EUS-FNA for solid liver lesions (35) showed good sensitivity for malignancy (82% to 94%), without reported complications and an impact on patient management. A second single-centre series of 41 patients (36) obtained similar convincing results for the diagnosis of malignancy.

Biopsies of the liver parenchyma can be obtained in nonmalignant diseases under EUS guidance. In 21 patients with suspected parenchymal disease, liver biopsies had a mean length of 9 mm, and contained two complete portal tracts and three partial portal tracts (37), with a diagnosis made in 19 patients. In a second study (38), nine patients were evaluated and, after a mean of two biopsy samples, five to eight complete portal tracts were available for analysis. A histological diagnosis was established in all patients and no procedure-related complication was reported. All nine patients had normal platelet counts and prothrombin time, except for mild thrombocytopenia in one. EUS-guided liver biopsy has not been directly compared with percutaneous or transjugular biopsy (39). Coagulopathy (platelets <50,000/mm3; international normalized ratio >1.5) contraindicates a US-guided liver biopsy. Therefore, sampling of liver parenchyma can be performed and may be cost effective in patients who already have an indication for EUS evaluation.

EUS is a valuable tool in the workup of biliary tract lesions. It may help differentiate cholangiocarcinoma from other malignancies and from benign diseases. In most published series, EUS was used in patients who had inconclusive results after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or CT-guided biopsy (40–43). It was also reported to be useful in the staging of patients with proven cholangio-carcinoma and hilar lymph nodes of unknown cause because FNA helped classify the lymphatic extension (44,45).

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES.

The usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography in the evaluation of liver diseases is summarized in Table 1. Analysis of the venous collateral pathways around the esophagus and the stomach in patients with PHT using a combination of EUS and Doppler techniques has improved our understanding of the pathophysiology of EGV (46). Compared with conventional upper endoscopy, it is as accurate for evaluating EV, and more accurate for diagnosing GV and differentiating them from other submucosal lesions. Analysis of the collateral vessels of EGV helped understand the role of peri-ECV and PfV in the formation of EVs and their recurrence after successful endoscopic eradication (47).

The role of EUS in the therapeutic algorithm for GEV remains to be defined. It could be used to better evaluate the risk of recurrence and rebleeding of EV (48), or as a therapeutic tool to perform sclerotherapy of feeder vessels. It could also help to stratify patients who are at risk for bleeding, and provide support for more aggressive therapy with frequent endoscopic treatments, or a combined endoscopic and pharmaceutical approach. EUS can help confirm the eradication of GV after histoacryl injection. It can be used in the preoperative evaluation of patients before surgery for GV (49,50).

EUS-guided FNA is a reliable and safe approach for sampling lesions in cirrhotic patients with coagulopathy (50,51). Main biliary tract, hilar and left liver lesions are accessible, and EUS is an interesting option for smaller lesions, if US or CT-guided sampling is judged to be nonfeasible, or if malignancy remains to be excluded even after a negative CT scan. Liver biopsy in a nonmalignant setting cannot currently be considered superior to a transjugular approach because it is contraindicated in the presence of coagulopathy.

Experiments in animal models and in humans enabled tissue sampling, portal vein catheterization and hemodynamic assessments in patients with PHT, which illustrates the vast potential of EUS. Its use has some limitations due to its availability. It is currently performed mostly in tertiary centres, and cannot be expected to be available to evaluate cirrhotic patients routinely. This limits the use of this technique to specific situations that have yet to be clearly defined. Better access to equipment and training is expected to increase its use in hepatology in the near future.

TABLE 1.

Endoscopic ultrasonography in hepatology

| Portal hypertension |

| Imaging of collateral circulation |

| Hemodynamic evaluation |

| Evaluation of the prognosis (rebleeding risk) |

| Treatment |

| Guided variceal sclerotherapy |

| Evaluation of gastroesophageal obliteration |

| Liver tumours |

| Imaging |

| Diagnosis (tissue sampling) |

| Evaluation of lymphatic extension |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs Manon Bourcier for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ginès A, Fernandez-Esprrach G. Endoscopic ultrasonography for the evaluation of portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lisi S, Buscarini E. Endoscopic ultrasonography and portal hypertension: Where are we in 2009 ? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1327–32. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283316231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sgouros SN, Vasiliadis KV, Pereira SP. Systematic review: Endoscopic and imaging-based techniques in the assessment of portal haemodynamics and the risk of variceal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:965–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baik SK. Hemodynamic evaluation by Doppler ultrasonography in patients with portal hypertension: A review. Liver Int. 2010;30:1403–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YT, Chan FKL, Ching JYL, et al. Diagnosis of gastroesophageal varices and portal collateral venous abnormalities by endosonography in cirrhotic patients. Endoscopy. 2002;34:391–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-25286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane L, Kahaleh M, Shami VM, et al. Comparison of the grading of esophageal varices by transnasal endoluminal ultrasound and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:806–10. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00482-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiano TD, Adrain AL, Vega KJ, Liu JB, Black M, Miller LS. High-resolution endoluminal sonography assessment of the hematocystic spots of esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:424–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irisawa A, Shibukawa G, Obara K, et al. Collateral vessels around the esophageal wall in patients with portal hypertension: Comparison of EUS imaging and microscopic findings at autopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:249–53. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irisawa A, Obara K, Sato Y, et al. EUS analysis of collateral veins inside and outside the esophageal wall in portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:374–80. doi: 10.1053/ge.1999.v50.97777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irisawa A, Obara K, Bhutani MS, et al. Role of para-esophageal collateral veins in patients with portal hypertension based on the results of endoscopic ultrasonography and liver scintigraphy analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:309–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katutani H, Hino S, Ikeda K, et al. Use of the curved linear-array echo-endoscope to identify patients with gastro-renal shunts in patients with gastric fundal varices. Endoscopy. 2004;36:710–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elsamman MK, Fujiwara Y, Kameda N, et al. Predictive factors of worsening of esophageal varices after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration in patients with gastric varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2214–21. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiechowska-Kozlowska A, Bialek A, Milkiewicz P. Prevalence of deep rectal varices in patients with cirrhosis: An EUS-based study. Liver Int. 2009;29:1202–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai L, Brugge WR. Endoscopic ultrasound is a sensitive and specific test to diagnose portal venous system thrombosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:40–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiersema MJ, Chak A, Kopecky KK, Wiersema LM. Duplex Doppler endosonography in the diagnosis of splenic vein, portal vein, and portosystemic shunt thrombosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoskins PR, Soldan M, Fortune S, Inglis S, Anderson T, Plevris J. Validation of endoscopic ultrasound measurement flow rate in the azygos vein using a flow phantom. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:1957–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassem AM, Salama ZA, Zakaria MS, Hassaballah M, Hunter MS. Endoscopic ultrasonographic study of the azygos vein before and after endoscopic obliteration of esophagogastric varices by injection sclerotherapy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:630–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishida N, Giostra E, Spahr L, Mentha G, Mitamura K, Hadengue A. Validation of color Doppler EUS for azygos blood flow measurement in patients with cirrhosis: Application to the acute hemodynamic effects of somatostatin, octreotide, or placebo. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:24–30. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pontes JM, Leitão MC, Portela F, Nunes A, Freitas D. Endosonographic Doppler-guided manometry of esophageal varices: Experimental validation and clinical feasibility. Endoscopy. 2002;34:966–72. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giday SA, Clarke JO, Buscaglia JM, et al. EUS-guided portal vein catheterization: A promising novel approach for portal angiography and portal vein pressure measurements. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:338–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giday SA, Ko CW, Clarke JO, et al. EUS-guided portal vein carbon dioxide angiography: A pilot study in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:814–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buscaglia JM, Dray X, Shin EJ, et al. A new alternative for a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: EUS-guided creation of an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:941–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irisawa A, Saito A, Obara K, et al. Endoscopic recurrence of esophageal varices is associated with the specific EUS abnormalities: Severe peri-esophageal collateral veins and large perforating veins. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:77–84. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.108479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konishi Y, Nakamura T, Kida H, Seno H, Okazaki K, Chiba T. Catheter US probe EUS evaluation of gastric cardia and perigastric vascular structures to predict esophageal variceal recurrence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:197–203. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato T, Yamazaki K, Toyota J, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonographic evaluation of hemodynamics related to variceal relapse in esophageal variceal patients. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:126–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Matsutani S, Umebara K, et al. EUS changes predictive of recurrence for esophageal varices in patients treated by combined endoscopic ligation and sclerotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:611–17. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuramochi A, Imazu H, Kakutani H, Uchiyama Y, Hino S, Urashima M. Color Doppler endoscopic ultrasonography in identifying groups at a high-risk of recurrence of esophageal varices after endoscopic treatment. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:219–24. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1992-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lahoti S, Catalano MF, Alcocer E, Hogan WJ, Geenen JE. Obliteration of esophageal varices using EUS-guided sclerotherapy with color Doppler. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:331–3. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Paulo GA, Ardengh JC, Nakao FS, Ferrari AP. Treatment of esophageal varices: A randomized controlled trial comparing endoscopic sclerotherapy and EUS-guided sclerotherapy of esophageal collateral veins. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero-Castro R, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Jimenez-Saenz M, et al. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate in perforating feeding veins in gastric varices: Results in 5 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:402–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crowe DR, Eloubeidi MA, Chhieng DC, Jhala NC, Jhala D, Eltoum IA. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of hepatic lesions: Computerized tomographic-guided versus endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA. Cancer. 2006;108:180–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maheshwari A, Kantsevoy S, Jagannath S, Thuluvath PJ. Endoscopic ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:325–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh P, Erickson RA, Mukhopadhyay P, et al. EUS for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma: Results of a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Awad SS, Fagan S, Abudayyeh S, Karim N, Berger DH, Ayub K. Preoperative evaluation of hepatic lesions for the staging of hepatocellular and metastatic liver carcinoma using endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Surg. 2002;184:601–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeWitt J, LeBlanc J, McHenry L, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of solid liver lesions: A large single-center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1976–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollerbach S, Willert J, Topalidis T, Reiser M, Schmiegel W. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of liver lesions: Histological and cytological assessment. Endoscopy. 2003;35:743–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeWitt J, McGreevy K, Cummings O, et al. Initial experience with EUS-guided Tru-cut biopsy of benign liver disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gleeson FC, Clayton AC, Zhang L, et al. Adequacy of endoscopic ultrasound core needle biopsy specimen of non malignant hepatic parenchymal disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1437–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.E Cholongitas E, Quaglia A, Samonakis D, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy: How good is it for accurate histological interpretation? Gut. 2006;55:1789–94. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.090415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeWitt J, Misra VL, Leblanc JK, McHenry L, Sherman S. EUS-guided FNA of proximal biliary stritures after negative ERCP brush cytology results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:325–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Knoefel WT, et al. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in potentially operable patients with negative brush cytology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:45–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, Jhala NC, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of suspected cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:209–13. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Sriram PV, et al. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:532–40. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gleeson FC, Rajan E, Levy MJ, et al. EUS-guided FNA of regional lymph nodes in patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:438–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsukinaga S, Imazu H, Uchiyama Y, et al. Diagnostic approach using endosonography guided fine needle aspiration for lymphadenopathy in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3758–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sgouros SN, Bergele C, Avgerinos A. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of portal hypertension. Where are we next? Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Saadany M, Jalil S, Irisawa A, Shibukawa G, Ohira H, Bhutani MS. EUS for portal hypertension: A comprehensive and critical appraisal of clinical and experimental indications. Endoscopy. 2008;40:690–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boustière C, Castellani P. Place de l’échoendoscopie dans la prise en charge du risque hémorragique chez le cirrhotique. Hépato-Gastro. 2007;14:101–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsieh JS, Wang WM, Perng DS, Huang CJ, Wang JY, Huang TJ. Modified devascularization surgery for isolated gastric varices assessed by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:666–71. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsieh JS, Jan CM, Lu CY, Chen FM, Wang JY, Huang TJ. Preoperative evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography and portography in selecting devascularization surgery for esophagogastric varices. Ann Surg. 2005;71:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.TenBerge J, Hoffman BJ, Hawes, et al. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of the liver: Indications, yield, and safety based on an international survey of 167 Cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:859–62. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.124557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]