Abstract

Two sons of a consanguineous marriage developed biventricular cardiomyopathy. One boy died of severe heart failure at the age of 6 years, the other was transplanted because of severe heart failure at the age of 10 years. In addition, focal palmoplantar keratoderma and woolly hair were apparent in both boys. As similar phenotypes have been described in Naxos disease and Carvajal syndrome, respectively, the genes for plakoglobin (JUP) and desmoplakin (DSP) were screened for mutations using direct genomic sequencing. A novel homozygous 2 bp deletion was identified in an alternatively spliced region of DSP. The deletion 5208_5209delAG led to a frameshift downstream of amino acid 1,736 with a premature truncation of the predominant cardiac isoform DSP-1. This novel homozygous truncating mutation in the isoform-1 specific region of the DSP C-terminus caused Carvajal syndrome comprising severe early-onset heart failure with features of non-compaction cardiomyopathy, woolly hair and an acantholytic form of palmoplantar keratoderma in our patient. Congenital hair abnormality and manifestation of the cutaneous phenotype in toddler age can help to identify children at risk for cardiac death.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00392-011-0345-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Desmoplakin, Juvenile biventricular cardiomyopathy, Palmoplantar keratoderma

Introduction

Juvenile cardiomyopathies are serious disorders often necessitating cardiac transplantation. Juvenile biventricular cardiomyopathy is usually caused by early-onset forms of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Apart from non-syndromic forms of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) and DCM, cardiocutaneous syndromes have also been described: Naxos disease [14] and Carvajal syndrome [6]. Both show an association of cardiomyopathy with woolly hair and palmoplantar keratoderma. Naxos disease exhibits a rather typical ARVD-phenotype, while in Carvajal syndrome left ventricular failure often predominates. As desmosomes play an important role for mechanical stability of epithelia, it seems obvious that the skin is affected by alterations in desmosomal proteins as well. In fact, Naxos syndrome is caused by a recessive mutation in the plakoglobin (JUP) gene [10]. For Carvajal syndrome, two different homozygous mutations in desmoplakin (DSP) have been described so far: a truncating frameshift [11] and a truncating nonsense mutation [18]. Recently, a heterozygous insertion of 30 base pairs (bp) in exon 14 was reported as well [12]. Here, we describe a novel recessive deletion c.5208_5209delAG (p.G1737fsX1742) leading to Carvajal syndrome with severe juvenile biventricular cardiomyopathy clinically appearing as non-compaction cardiomyopathy with associated skin and hair phenotype.

Materials and methods

Histology

Explanted cardiac muscle tissue and plantar keratosis were routinely fixed in 4% formalin and embedded in paraffin after graded ethanol dehydration. Routine staining included hematoxylin–eosin and Elastica-van Gieson.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Cardiac morphology and function in the index patient were examined using a clinical MR scanner with a field strength of 1.5 Tesla. The ratio of non-compacted to compacted myocardium (NC/C ratio) was calculated in diastole for each of the three long-axis views in the four-chamber view according to Peterson et al., 2005 [13]; only the maximal ratio was then used for analysis. An NC/C ratio >2.3 in diastole distinguished pathological non-compaction.

Molecular analysis

To allow an identification of the underlying genetic defect, DNA was extracted from EDTA-anticoagulated blood by phenol chloroform extraction. The gene for DSP was screened for mutations using exon flanking primers (see online supplement). Sequence reactions were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3130.

Western blotting

Snap frozen skin biopsies from the patient and normal controls were homogenized in RIPA-buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% DOC (doeoxycholic acid), 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche); 40 μg of each sample was separated on 8% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to Hybond-C nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Membranes were blocked with PBS containing 5% (w/v) milk powder and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. Primary antibody incubation was carried out overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 5% (w/v) milk powder and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. Secondary antibodies were conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Proteins were visualized using the ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Antibodies used for Western blotting were DSP 1/2 goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) used at a 1:500 dilution and the GAPDH mouse monoclonal antibody used at 1:5,000; both were incubated with respective secondary antibodies (Amersham).

Results

Patients

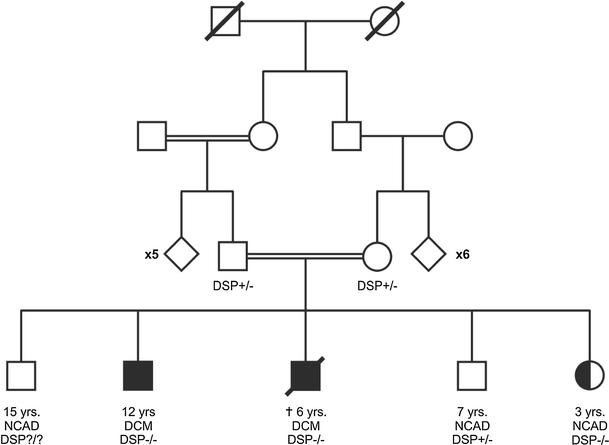

Two sons of a consanguineous marriage (Fig. 1) became affected by a global DCM at the ages of 4 and 5 years and presented a focal form of palmoplantar keratoderma. Their parents and one brother appeared unaffected based on cardiologic (history, physical examination, electrocardiography, 2D-echocardiography) and dermatologic evaluation. While the younger sister also showed skin disorders, the fourth brother was not evaluated.

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of studied family. Filled squares (males) indicate cardiac involvement and skin/hair abnormalities; half circles (females) indicate skin abnormalities; diagonal lines indicate deceased individuals; diamonds indicate individuals of either gender; double lines indicate consanguinity. NCAD No cardiac abnormality detected

One of the affected boys died of severe heart failure at the age of 6 years, 1 year after the initial diagnosis. We could not clinically evaluate this child, but studied clinical reports from an academic pediatric cardiology department. Echocardiography of the deceased boy described severe left ventricular (LV) dilation (59 mm) and global systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction LVEF 11%): he died of terminal heart failure.

The mother showed a borderline ejection fraction (58%) and hypertrabeculation of the LV myocardium on MRI. In addition, a slight diffuse apical late enhancement was noticed. There were no signs of fatty infiltration. The MRI of the father was entirely normal.

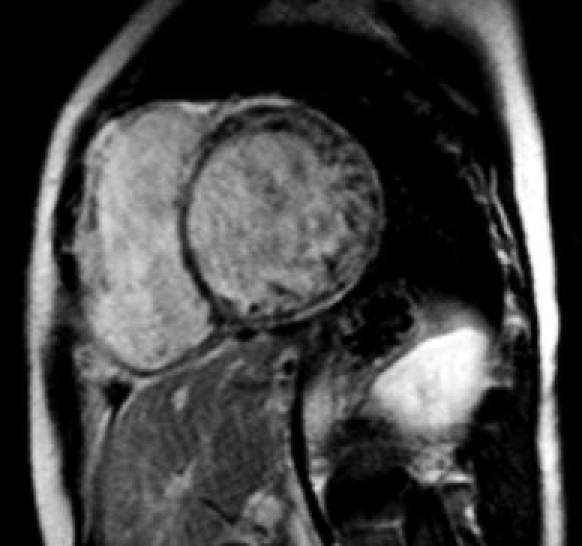

At the age of 2 years, his brother developed hyperkeratosis on the soles of his feet at points of pronounced pressure (Fig. 2). At the age of 5 years, he was diagnosed with a dilated LV and apical non-compaction of the LV myocardium. The initial echocardiogram demonstrated LVEF of 26%. At the age of 9 years, the index patient was still functionally compensated. MRI showed severe dilation of both ventricles and LVEF of 26% with pronounced trabeculation (Fig. 3 and suppl. Fig. 3). Additionally, patchy late enhancement and spots of signal enhancement on pre-contrast T1-images (right ventricle) were detected (images not shown). At the age of 10 years, heart transplantation was performed because of worsening functional capacity and the appearance of ventricular tachycardias.

Fig. 2.

Clinical presentation of the index patient at the age of 9 years. a, b The patient presented with typical woolly hair and focal hyperkeratosis at pressure points of the left hand (c) and on the sole of the right foot (d)

Fig. 3.

MRI, short axis view, SSFP (steady state free precession) late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequence, patchy myocardial contrast-enhancement (see also suppl. Fig. 3)

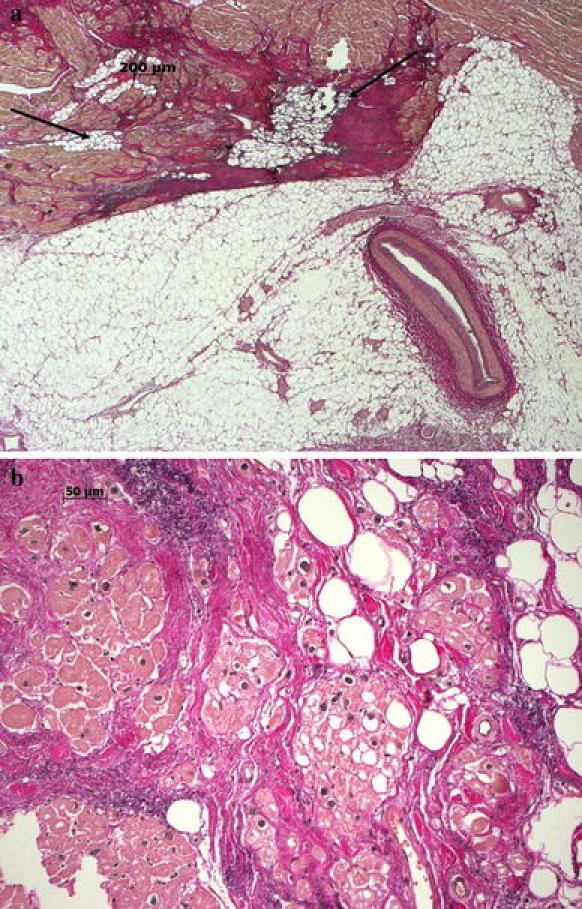

Histology

The explanted heart showed biventricular hypertrophy with hypertrabeculation. Endomyocardial and patchy fibrosis of the myocardium were evident in both ventricles. Furthermore, the subepicardial zone, especially of the right ventricular myocardium, showed fibrotic scar formation and regressive atrophy of the cardiomyocytes with accompanying focal fatty tissue formation in these areas (Fig. 4). However, there was no transmural fibrofatty replacement of the right ventricular myocardium. In particular, there was no widening of the intercellular space and the submembranous attachment plaques; anchoring filaments were readily visible.

Fig. 4.

Elastica van Gieson stainings. a Subepicardial zone with intensive fibrosis and focal fibrofatty replacement of the right ventricular myocardium (arrows). The coronary artery shows slight intimal fibrosis. b Higher magnification to show focal fibrofatty replacement. The cardiomyocytes exhibit regressive changes with vacuolization of the cytoplasm and nuclear enlargement

DSP was regularly detectable in intercalated discs; staining intensity was comparable to that seen in normal hearts. Furthermore, connexin 43 and vinculin were localized with normal intensity at the intercalated discs. Desmin and alpha-actinin appeared regularly distributed (data not shown).

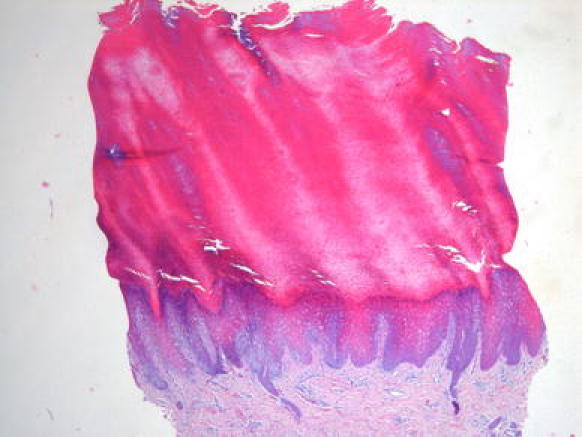

Histological examination of a plantar keratosis showed massive orthohyperkeratosis and acanthosis of the epidermis with small acantholytic clefts between neighboring keratinocytes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Histology of a focal plantar keratosis showing massive orthohyperkeratosis and acanthosis of the epidermis with small intercellular clefts (acantholysis) (hematoxylin–eosin stain)

Molecular genetics

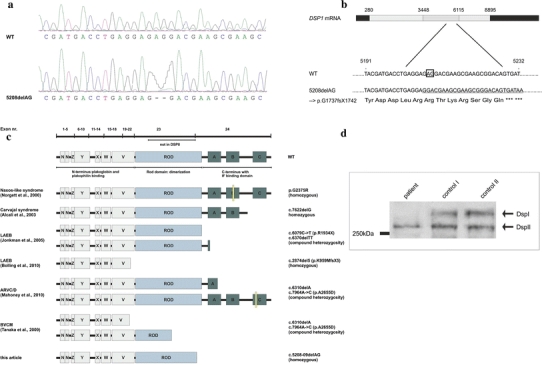

Analysis of the index patient’s genomic DNA revealed a homozygous 2 bp deletion in exon 23 of DSP which was neither described in the human genome, nor detected in 180 chromosomes of a control population (Fig. 6). The sister was also tested homozygous, while the patient’s parents and one brother were heterozygous for this mutation.

Fig. 6.

a The 2 bp deletion produced a frameshift resulting in seven new amino acids (underlined) and b a premature translation stop codon (asterisk). c Schematic view of DSP mutations affecting the C-terminus; yellow bars indicate amino acid substitution d Western blot analysis of DSP-1 and -2 expression in human skin

DSP is characterized by an N-terminal plakoglobin/plakophilin binding domain, the central coiled-coil rod dimerization domain and a C-terminal intermediate filament (IF) binding domain. The deletion (5208delAG) affects the coding nucleotides 5,208 and 5,209 within exon 24, respectively, and causes a frameshift with a subsequent premature stop codon after seven aberrant codons. The DSP gene encodes two different splice isoforms. The longer peptide DSP-1 is the dominant isoform in cardiac tissues [18] and contains the entire exon 23, whereas DSP-2 uses an internal splice donor site and therefore lacks 599 amino acids compared to DSP-1.

The 5208delAG mutation is downstream of the internal splice donor site and hence exclusively appears in DSP-1. Therefore, it should lead to an isoform-specific truncation of the cardiac isoform DSP-1. As the index patient is homozygous for the mutation, no full-length DSP-1 could be produced as proved by western blot analysis (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Early-onset cardiomyopathies are severe diseases. The National Australian Childhood Cardiomyopathy Study Group recently published survival rates for pediatric DCM. Freedom from death or transplantation was reduced to 72% 1 year after presentation and to 63% at 5 years [7]. It appears imperative to make all efforts to improve the prognosis of such children. Identification of causative genetic defects can help in several ways. First, it allows separation of family members at risk from those who need not be closely monitored. Close monitoring of individuals at risk can help initiate treatment of both, heart failure and arrhythmias at an early point of the disease course. Second, it offers opportunities for prenatal diagnosis. Third, the identification of disease-causing mutations enables acquiring a deeper understanding of the underlying pathophysiology in this devastating condition.

Several pathways for cardiac diseases have already been identified using this approach. Mutations in ion channel genes were identified in familial arrhythmias such as long-QT and Brugada syndromes [9]. Aberrations in sarcomeric genes can lead to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [2]. Disruption of desmosomal function is the unifying pathomechanism in ARVD [8]. For DCM, the picture is less clear. Apart from a high proportion of non-genetic forms, even familial DCM shows a high degree of genetic heterogeneity, with different subcellular systems being involved in the disease-causing process [16].

As the index patient had been diagnosed with DCM due to the strong left ventricular dysfunction, we would not have had a realistic chance to identify the underlying genetic defect in the family described, if there had been no additional phenotypes. The characteristic combination of biventricular cardiomyopathy, woolly hair and palmoplantar keratoderma known as Carvajal syndrome led us to assume that mutations in DSP could be the problem in this family. Finally, we identified a homozygous 2 bp deletion in this gene leading to a premature chain-termination mutation. At the age of 10, 5 years after the initial diagnosis, the index patient was transplanted. He was diagnosed with LV involvement, and at the time of explantation the heart showed severe biventricular involvement. According to findings by Sen-Chowdhry et al., [17] who identified three distinct patterns of disease expression, the phenotype of the index patient allows grouping the genotype into the left-dominant disease expression pattern. The phenotypic differences observed between the index patient and the homozygous younger sister, however, could be accounted to her young age, since both the index patient and the deceased brother were free of cardiac involvement until the ages of 4 and 5 years.

DSP is a major constituent of the desmosome. Like several other desmosomal genes, DSP belongs to disease genes that cause ARVD. In addition, DSP is highly expressed in epithelia where desmosomes are important for mechanical integrity. It is therefore not surprising that, apart from cardiac alterations, mutations in DSP can also lead to skin phenotypes and hair abnormalities. Even isolated cutaneous phenotypes without cardiac disease can be caused by DSP mutations, i.e., striate palmoplantar keratoderma, skin-fragility/woolly hair syndrome and lethal acantholytic epidermolysis bullosa (LAEB). Missense, nonsense and truncating frameshift mutations have been identified in these cases (Fig. 6) [1, 5, 9, 11]. Even though an obvious phenotype–genotype correlation regarding DSP mutations has not yet been drawn, it is tempting to speculate that truncations/modifications affecting the C-terminal domain of DSP-1 predispose to cardiomyopathy due to present and previous studies.

For the specific syndromic phenotype of Carvajal syndrome, only three mutations have been described so far. Two exhibit a recessive trait. The homozygous deletion c.7901delG (p.K2542fsX2559) truncates DSP at the C-terminus [11], affecting both isoforms. A homozygous nonsense mutation (p.R1267X) in the DSP-1 specific region of exon 23 leads to shortening of the rod domain exclusively in DSP-1 [18]. Dominant mutations seem capable of producing similar phenotypes [3, 4, 12, 15]. The frameshift mutation G1737fsX1742 described here is situated in the DSP-1 specific region of exon 23, similar to the p.R1267X mutation. Since both alleles are affected, the truncation leads to complete loss of intact full-length DSP-1. Instead, only the truncated isoform was detectable in skin biopsies of this patient. Since DSP-2 is only expressed at very low levels in cardiac muscle and the fact that we found orthotopic DSP expression on immunohistopathology using an antibody recognizing the truncated part of DSP, we conclude that the truncated isoform was still incorporated into the desmosomes but lacked functional integrity eventually leading to the early onset of heart failure in the affected individual.

Conclusions

First, the novel homozygous truncating mutation in the isoform-1 specific region of the DSP C-terminus can lead not only to a severe early-onset form of DCM, woolly hair and an acantholytic form of palmoplantar keratoderma, but also to features of non-compaction. Second, this cardiomyopathy can occur in hearts with normally structured intercalated discs and desmin networks.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Conflict of interest

The authors have indicated that they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- DSP

Desmoplakin

- DCM

Dilative cardiomyopathy

- JUP

Plakoglobin

- ARVD

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

References

- 1.Alcalai R, Metzger S, Rosenheck S, et al. A recessive mutation in desmoplakin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, skin disorder, and woolly hair. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:319–327. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashrafian H, Watkins H. Reviews of translational medicine and genomics in cardiovascular disease: new disease taxonomy and therapeutic implications cardiomyopathies: therapeutics based on molecular phenotype. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1251–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azaouagh A, Churzidse S, Konorza T, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: a review and update. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauce B, Basso C, Rampazzo A, et al. Clinical profile of four families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy caused by dominant desmoplakin mutations. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1666–1675. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolling MC, Veenstra MJ, Jonkman MF et al (2010) Lethal acantholytic epidermolysis bullosa due to a novel homozygous deletion in DSP: expanding the phenotype and implications for desmoplakin function in skin and heart. Br J Dermatol 162:1388–1394 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Carvajal-Huerta L. Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma with woolly hair and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:418–421. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daubeney PE, Nugent AW, Chondros P, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of childhood dilated cardiomyopathy: results from a national population-based study. Circulation. 2006;114:2671–2678. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerull B, Heuser A, Wichter T, et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1162–1164. doi: 10.1038/ng1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonkman MF, Pasmooij AM, Pasmans SG, et al. Loss of desmoplakin tail causes lethal acantholytic epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:653–660. doi: 10.1086/496901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mckoy G, Protonotarios N, Crosby A, et al. Identification of a deletion in plakoglobin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with palmoplantar keratoderma and woolly hair (Naxos disease) Lancet. 2000;355:2119–2124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norgett EE, Hatsell SJ, Carvajal-Huerta L, et al. Recessive mutation in desmoplakin disrupts desmoplakin-intermediate filament interactions and causes dilated cardiomyopathy, woolly hair and keratoderma. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2761–2766. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norgett EE, Lucke TW, Bowers B, et al. Early death from cardiomyopathy in a family with autosomal dominant striate palmoplantar keratoderma and woolly hair associated with a novel insertion mutation in desmoplakin. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1651–1654. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen SE, Selvanayagam JB, Wiesmann F, et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Protonotarios N, Tsatsopoulou A, Patsourakos P, et al. Cardiac abnormalities in familial palmoplantar keratosis. Br Heart J. 1986;56:321–326. doi: 10.1136/hrt.56.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rampazzo A, Nava A, Malacrida S, et al. Mutation in human desmoplakin domain binding to plakoglobin causes a dominant form of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1200–1206. doi: 10.1086/344208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schonberger J, Seidman CE. Many roads lead to a broken heart: the genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:249–260. doi: 10.1086/321978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen-Chowdhry S, Syrris P, Ward D, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy provides novel insights into patterns of disease expression. Circulation. 2007;115:1710–1720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uzumcu A, Norgett EE, Dindar A, et al. Loss of desmoplakin isoform I causes early-onset cardiomyopathy and heart failure in a Naxos-like syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e5. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.