Abstract

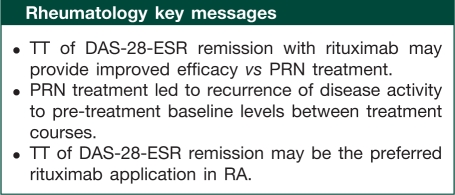

Objective. To assess the efficacy and safety profiles of two different rituximab retreatment regimens in patients with RA.

Methods. Four hundred and ninety-three RA patients with an inadequate response to MTX recruited into rituximab Phase II/III studies received further courses of open-label rituximab based on two approaches: (i) treatment to target (TT): patients assessed 24 weeks after each course and retreated if not in remission [DAS in 28 joints based on ESR (DAS-28-ESR) ≥ 2.6]; (ii) treatment as needed (PRN): patients retreated at the physician’s discretion ≥24 weeks following the first course and ≥16 weeks following further courses, if both swollen and tender joint counts were ≥8. All courses consisted of i.v. rituximab 2 × 1000 mg 2 weeks apart plus MTX. Observed data were analysed according to treatment strategy.

Results. Multiple courses of rituximab maintained or improved responses irrespective of regimen. TT provided tighter control of disease activity with significantly greater improvements in DAS-28-ESR and lower HAQ-disability index scores vs PRN. TT resulted in significantly more patients achieving major clinical response. PRN resulted in recurrence of disease symptoms between courses, with TT significantly reducing the incidence of RA flares. Despite more frequent retreatment with TT compared with PRN, the rates of serious adverse events and serious infections were comparable between regimens.

Conclusions. Retreatment with rituximab based on 24-week evaluations and to a target of DAS-28-ESR remission leads to improved efficacy and tighter control of disease activity compared with PRN without a compromised safety profile. TT may be the preferable rituximab treatment regimen for patients with RA.

Keywords: Methotrexate-inadequate responder, Treatment to target, Treatment as needed, Retreatment, Rituximab, Treatment strategy

Introduction

There is currently increasing interest in the tight control of RA by using disease activity measures to guide treatment decisions [1]. Treatment to target (TT) is a treatment strategy tailored to the individual patient, whereby patients are regularly monitored and treatment is adjusted in order to achieve a predefined level of disease activity, such as remission, within a certain period of time [2–6]. Tight control of disease is desirable for improved control of disease activity, but may also be associated with better longer term outcomes such as decreased progression of structural joint damage [1, 7] and improvement in functional capability [1, 4]. Recent guidelines and recommendations for RA treatment advocate this approach [6, 8, 9], and there is evidence of acceptance of tight disease control as a concept by the practising rheumatology community [10].

Rituximab is a therapeutic mAb that selectively targets CD20+ B cells. The combination of rituximab with MTX significantly improves disease symptoms in RA patients who have had an inadequate response to conventional DMARD therapy, and has been shown to improve disease symptoms and protect against joint damage in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors [11–13].

During the clinical development of rituximab in RA, two distinct retreatment regimens have been adopted. In initial studies, second and subsequent courses of rituximab treatment (hereafter referred to as retreatments) were administered based on the presence of a certain number of active joints and at the discretion of the treating physician. In more recent Phase III studies, the individual patient’s disease activity was assessed 24 weeks after each course of treatment, with further treatment required by protocol on the basis of this assessment, with the aim of achieving a target level of disease activity (DAS in 28 joints based on ESR; DAS-28-ESR <2.6). The 24-week time point for the assessment of disease activity was based on studies of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of rituximab, which have shown drug concentrations below the level of detection and evidence of returning peripheral B cells for many patients from this time point [12, 14, 15].

The objective of this analysis was to assess the differences in efficacy and safety of these two different rituximab retreatment regimens—TT and treatment as needed (PRN)—in patients with RA, with a view to defining an optimal retreatment regimen. The analysis was based on pooled data from the rituximab clinical development programme in biological-naïve patients who have had an inadequate response to MTX (MTX-IR).

Methods

Patients

Patients retreated with rituximab using the TT regimen were included from the Study Evaluating Rituximab's Efficacy in MTX iNadequate rEsponders (SERENE) [13] and MIRROR studies [16]. Patients retreated using the PRN regimen were included from the DANCER study [17] and the initial rituximab proof of concept study [14], together with their long-term extensions [18]. Supplementary figure A (available as supplementary data at Rheumatology Online) shows the number of patients recruited from each study along with the retreatment regimen the patients received. All patients were a minimum of 18 or 21 years of age (depending on the study) with RA diagnosed according to the revised 1987 ACR criteria [19]. Disease duration was at least 6 months. All patients had experienced an inadequate response to MTX despite current and ongoing MTX treatment. At study entry, patients had active disease defined as both a swollen joint count (66 joints) and a tender joint count (68 joints) ≥8 at screening and baseline. In addition, patients had a CRP level of ≥0.6 or 1.5 mg/dl (depending on the study) or an ESR ≥28 mm/h. Data from patients who were initially randomly assigned to receive placebo and who were subsequently switched to receive rituximab were included from the point of first administration of rituximab 2 × 1000 mg.

All studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to the principles outlined in the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Tripartite Guideline (January 1997). Studies were approved by the institutional review board or the ethics committee at each study site. All patients gave written informed consent. Long-term follow-up of the SERENE and MIRROR trials were pre-planned extensions of the original trials and no further ethics approval or informed consent were required. For the other studies, patients were transferred into separate long-term extension studies for which ethics approval and informed consent were obtained.

Treatment strategies

Patients treated using the TT regimen were assessed 24 weeks after each course of rituximab. Patients received retreatment if their DAS based on ESR [20] was ≥2.6. Patients whose DAS-28-ESR was <2.6 were assessed every 8 weeks (or sooner if required) and were retreated if and when DAS-28-ESR increased to ≥2.6. Patients were only permitted a third and subsequent courses of rituximab if they were considered by the treating physician to have benefited from either of the initial two courses.

Patients treated using the PRN regimen were assessed 24 weeks following their initial course of rituximab or placebo. Only patients achieving a reduction in swollen and tender joint counts of ≥20% were permitted retreatment with rituximab. A second course of rituximab was permitted if both tender and swollen joint counts were ≥8, and at the discretion of the treating physician. Patients were reassessed every 8 weeks for reconsideration of treatment (although unscheduled visits could occur at anytime for reassessment if required); however, further treatment courses were permitted no more frequently than every 16 weeks following each course, based on these criteria.

Procedures

All courses of rituximab 2 × 1000 mg were administered by i.v. infusion on Days 1 and 15 of each treatment course, with all infusions premedicated with 100 mg i.v. methylprednisolone. All patients continued to receive their pre-baseline dose of MTX (oral or parenteral) at a level not exceeding 25 mg/week. Concomitant glucocorticoids (≤10mg/day prednisolone or equivalent) and NSAIDs were permitted at stable doses. With the exception of rescue in the SERENE study, i.v. or i.m. glucocorticoids and additional DMARDs (non-biological or biological) were prohibited (in the SERENE study, four patients included in this analysis initiated rescue therapy with one additional non-biological DMARD between Weeks 16 and 23).

Assessments

Assessments of clinical outcomes and physical function were made at 8-weekly intervals with unscheduled visits at any time, as required. Clinical outcomes included DAS-28-ESR and durability of response determined by the proportion of patients achieving a major clinical response (defined as maintenance of ACR70 response for ≥6 months). Physical function was determined using the HAQ-disability index (HAQ-DI) [21]. The incidence of flare (defined as an increase in the patient’s DAS-28-ESR of >1.2 above their lowest value achieved during that specific course) within each treatment course was determined. The time interval between treatment courses for both regimens was also determined.

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded throughout the study and graded according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAEs), version 3. Serious AEs (SAEs) were defined as events that were fatal, immediately life-threatening, required hospitalization or prolongation of an existing period of hospitalization, were medically significant or required intervention to prevent one of the above outcomes. For classification purposes, original terms were assigned preferred terms using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 10.1. Infections were identified using a MedDRA basket of preferred terms and/or events identified as infections on the case report form. Serious infection events (SIEs) were defined as either SAE infections or infections treated with i.v. antibiotics.

Statistics

In this study, retrospective analyses were performed using pooled data from biologic-naïve MTX-IR patients, and using observed data pooled by treatment strategy, with no imputation methods applied. Efficacy outcomes (DAS-28-ESR and HAQ-DI) were included for up to 2 years after the initial dose of rituximab.

The time to retreatment by course was compared between retreatment groups using a non-parametric Wilcoxon test. The pre-course DAS-28-ESR value was defined as the value obtained before the first infusion of each rituximab course or the last known value before the baseline value if the former was missing. The mean pre-course DAS-28-ESR baseline values were compared between the TT and PRN groups using a t-test. The proportions of patients experiencing a disease flare by course and of those achieving a major clinical response were analysed using Pearson’s chi-square test.

To examine the differences in change in DAS-28-ESR and HAQ-DI over time between the retreatment regimen groups, analysis was performed using a repeated measures random effects model (using all data for a patient at all time points and including the patient as a random term). In order to adjust for potential baseline characteristic differences between the TT and PRN regimen groups, a propensity score model predicting the probability of being in the TT or PRN retreatment groups was generated using multivariable logistic regression. These propensity scores were then included in the repeated measures model as a covariate. Variables that were included in the propensity score adjustment were baseline characteristics (Table 1), in addition to race (white, black and other), baseline height, baseline weight, patient global assessment, patient-assessed pain, physician global assessment and DAS-28 based on CRP. Safety data were not limited and were based on all available data from all patients. Overall rates of AEs and infections per 100 patient-years were calculated.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Rituximab (2 × 1000 mg) PRN (n = 257) | Rituximab (2 × 1000 mg) TT (n = 236) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender: female, % | 78 | 82 |

| Age, mean (s.d.) years | 52 (11.3) | 52 (12.5) |

| Median disease duration (IQR), years | 8.5 (3.9–14.9) | 3.6 (1.5–9.9) |

| No. of previous DMARDs, mean (s.d.) | 2.0 (1.20) | 1.2 (1.19) |

| Concomitant steroids, % | 49 | 48 |

| Concomitant NSAIDs, % | 53 | 56 |

| Swollen joint count (0–66), mean (s.d.) | 20 (10.8) | 19 (10.2) |

| Tender joint count (0–68), mean (s.d.) | 32 (15.1) | 30 (14.8) |

| CRP, mean (s.d.), mg/l | 3.1 (3.44) | 2.1 (2.44) |

| ESR, mean (s.d.), mm/h | 42.7 (24.2) | 45.1 (27.1) |

| HAQ-DI (0–3 range), mean (s.d.) | 1.7 (0.57) | 1.6 (0.64) |

| DAS-28-ESR, mean (s.d.) | 6.7 (0.95) | 6.6 (1.03) |

| RF+, % | 81 | 73 |

| Anti-CCP+, % | 78 | 80 |

Data are mean (±SD) or number (%) unless otherwise stated. Anti-CCP, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Results

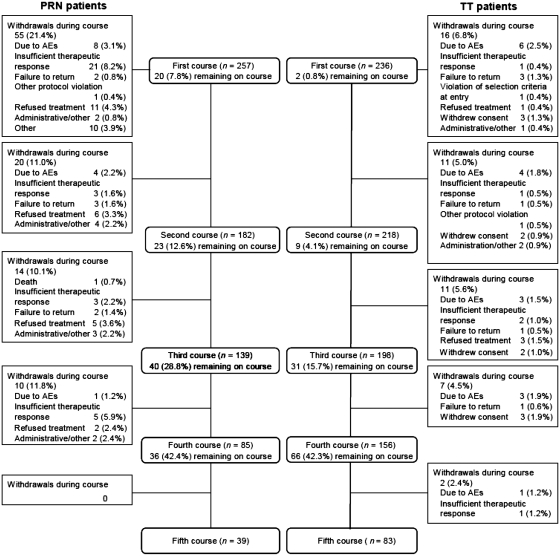

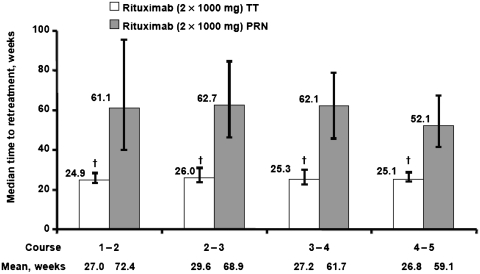

Overall, a total of 257 patients were included in the PRN group and 236 patients were included in the TT group. Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics were generally well balanced between the groups, with the exception of median disease duration, which was higher in the PRN group than the TT group (8.5 vs 3.6 years, respectively) (Table 1). Over the first four rituximab courses, a higher proportion of patients withdrew from the PRN group (39% overall) than from the TT group (19% overall). The most common reasons for study withdrawal in the PRN group included insufficient therapeutic response (12%) and treatment refusal (9%). Withdrawals due to AEs were similar across groups: 5% in the PRN group and 7% in the TT group (Fig. 1). In the PRN group, 21% of patients withdrew during the first course and 11% during the second course, compared with 7 and 5% of patients in the TT group withdrawing during the first and second courses, respectively. The two retreatment strategies resulted in significant differences in the time between treatment courses. Within the PRN group, the median time to retreatment for the first four courses was 52–63 weeks compared with ∼25–26 weeks for the TT group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition.

Fig. 2.

Median time to retreatment with rituximab 2 × 1000 mg by course of rituximab. †P < 0.001 (unadjusted for multiple comparisons). Error bars represent interquartile range (Q1–Q3).

Clinical outcomes

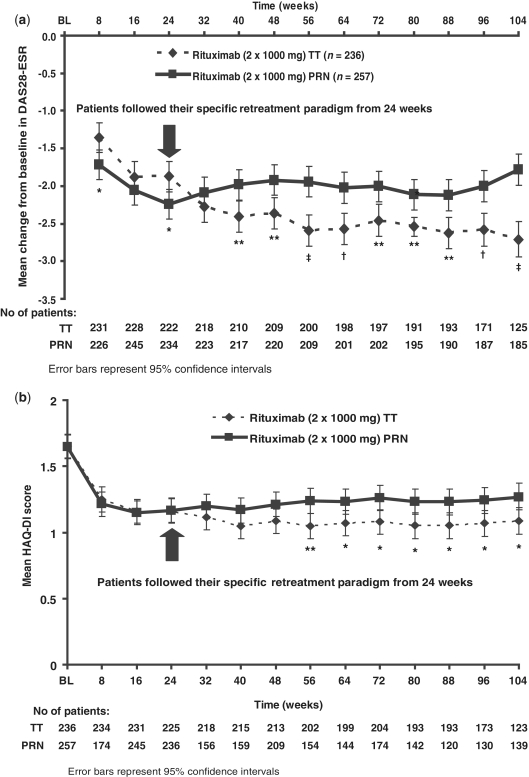

Following the initial course of rituximab, both treatment regimens demonstrated significant improvements in disease activity and physical function, as evidenced by decreases in both DAS-28-ESR and HAQ-DI compared with pre-treatment baseline values (Fig. 3). Despite a slightly greater initial decrease in disease activity from baseline to Week 24 in the PRN group than in the TT group, consistently greater mean changes in DAS-28-ESR were observed in patients treated with the TT regimen from 24 weeks and over the longer term to Week 104 (Fig. 3a). Having adjusted for baseline characteristics, these differences (ranging from 0.42 to 0.93 points) were statistically significant from Week 40. A similar pattern of improvement was observed for physical function throughout the 2-year observation period, with consistently lower mean HAQ-DI scores being achieved in the TT compared with the PRN group (Fig. 3b). After adjusting for baseline characteristics, these differences were statistically significant from Week 56. Significantly more patients treated using the TT regimen achieved a major clinical response compared with patients in the PRN group (12.3 vs 5.1%; P < 0.05). Patients not responding to the initial treatment course [as defined by a European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) non-response] demonstrated some ability to respond to a subsequent treatment course. Following the initial course of rituximab, 50/257 (19.5%) and 66/236 (28%) PRN and TT patients, respectively, were classed as EULAR non-responders at 24 weeks. A second course of rituximab was received by 36/50 (72%) and 65/66 (98.5%) PRN and TT non-responders, respectively, with good or moderate EULAR responses being achieved by 60.6 and 57.4% of patients in these groups, respectively, 24 weeks later.

Fig. 3.

Adjusted least square mean change from baseline in DAS-28-ESR (a) and adjusted least square mean HAQ-DI over time (b). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; †P < 0.001; ‡P < 0.0001 (all unadjusted for multiple comparisons). Error bars represent 95% CI.

Control of disease within treatment courses

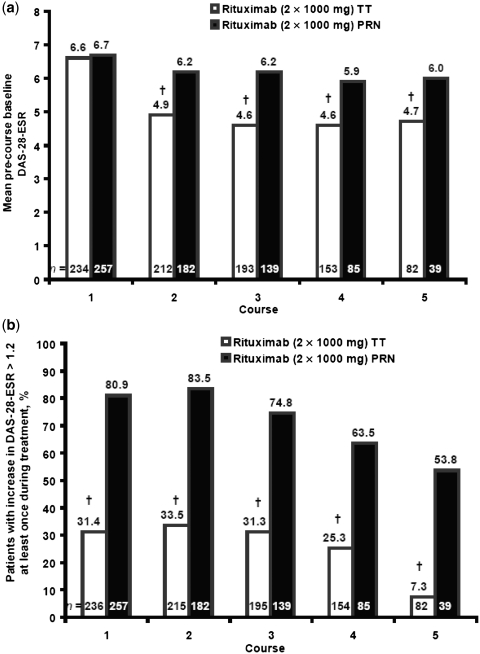

Measures of disease activity immediately before each treatment course indicated that there was significantly greater control of disease activity throughout each retreatment course in patients treated according to the TT regimen. In these patients, the mean DAS-28-ESR immediately before each course was consistently and statistically significantly lower (4.6–4.9) than that observed pre-rituximab (6.6) (Fig. 4a). In contrast, in patients treated according to the PRN regimen, mean DAS-28-ESR before each course (5.9–6.2) was similar to that pre-rituximab (6.7), indicating loss of response during each course with this regimen (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Mean pre-course baseline DAS-28-ESR by course of rituximab (a) and patients with an increase in DAS-28-ESR of 1.2 above the lowest DAS-28-ESR within the course (b). †P < 0.001, t-test of change in DAS-28-ESR, within groups (a). †P < 0.001, Pearson’s chi-square between group difference (b).

Greater control of disease activity in the TT group was also demonstrated by a significantly lower proportion of patients experiencing worsening of RA during each course of rituximab (Fig. 4b). Over five courses, a disease flare occurred in 7–34% of patients in the TT group compared with 54–84% of patients in the PRN group.

Safety outcomes

The number of patient-years of exposure was 977 (over a maximum of 7.40 years) in the PRN group and 450 (over a maximum of 2.77 years) in the TT group (Table 2). Despite the higher frequency of administration of rituximab in the TT group (median number of courses: four in the TT group vs three in the PRN group), the safety profiles for each regimen were generally comparable. Although the overall rate of AEs was somewhat higher in the TT group compared with the PRN group (364.3 vs 255.0 per 100 patient-years, respectively), the rates of SAEs, including SIEs, were comparable between groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of AEs and SAEs

| Outcome | Rituximab (2 × 1000 mg) PRN (n = 257) | Rituximab (2 × 1000 mg) TT (n = 236) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean years of exposure (minimum, maximum) | 3.95 (0.23, 7.40) | 1.97 (0.28, 2.77) |

| Patient-years | 977 | 450 |

| AEs/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 255.0 (245.2, 265.2) | 364.3 (347.1, 382.4) |

| SAEs/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 16.0 (13.6, 18.7) | 12.0 (9.2, 15.7) |

| Infections/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 69.7 (64.6, 75.1) | 111.9 (102.5, 122.1) |

| Serious infections/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 3.4 (2.4, 4.8) | 2.2 (1.2, 4.1) |

The profile of AEs and SAEs was in line with that typically observed with rituximab, and no new safety concerns were identified. In both groups, the most frequently reported AEs were infusion-related reactions, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, exacerbation of RA and urinary tract infection, with bronchitis also frequently reported only in the PRN group. The majority of individual SAEs occurred in <1% of patients. Within the TT group the only SAE to occur in >1% of patients was OA (2%); whereas SAEs occurring in >1% of PRN patients included exacerbation of RA (4%), OA (3%), pneumonia (2%), lower respiratory tract infection (2%), fall (2%) and myocardial infarction (2%).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of MTX-IR patients receiving multiple courses of rituximab suggests that a retreatment regimen based on 24-week evaluations and a TT approach is associated with both improved efficacy and tighter control of disease activity compared with PRN treatment. Over a 2-year period, the TT regimen was associated with significantly greater mean improvement in disease activity and lower HAQ-DI scores than the PRN regimen. From Week 40, the difference in disease activity resulting from the two approaches was statistically significant and considered to be clinically relevant. Furthermore, significantly fewer patients treated using the TT regimen experienced disease flares, with tighter control of disease activity throughout each rituximab treatment course.

It is important to note that although the TT regimen was associated with an increased frequency of dosing, there did not appear to be a significant impact on safety associated with this regimen. Using all available data, the rates of SAEs and SIEs seen with the TT strategy were comparable with those observed in PRN-treated patients.

Although the results of these described analyses are clinically interesting, some important issues need to be taken into consideration with regard to their interpretation. This study was not a controlled, randomized assessment with a pre-specified analysis plan; instead, data were pooled from patients recruited into Phase II and III clinical studies conducted over several years and in different geographical locations. Therefore, this analysis has its limitations. Patient withdrawals occurred more frequently in the PRN population than in the TT population, the most common reason being insufficient response (despite the slightly lower incidence of EULAR non-response following the first course of treatment in the PRN population).

It is of note that patients treated according to the PRN regimen were primarily recruited during the early development of rituximab, when data regarding the efficacy and safety of rituximab in RA were limited. This could have influenced both the population of patients recruited into these studies as well as the frequency of retreatment with rituximab according to the PRN regimen, with physicians being more reluctant to administer repeat courses due to the limited safety information on long-term B-cell depletion. Additionally, there was some delay in the transition to the long-term extension studies for patients following the PRN regimen. Differences in the patient populations recruited into the studies were low, although disease duration was longer in the PRN population, possibly indicating a selection bias for these patients. As the numbers of patients withdrawing were small compared with the overall retreatment populations, comparisons are therefore very limited. Propensity scores were used to adjust for any differences between groups to provide estimates of treatment effect. Another limitation of this analysis is that the return of disease activity to pre-rituximab levels in the PRN group is not unexpected as patients were required to have both tender and swollen joint counts ≥8 to qualify for retreatment, which were the same criteria as for inclusion. Therefore, these data should be interpreted with caution.

It is important to acknowledge that somewhat subjective investigator-assessed criteria were used for assessments of response to initial treatments and for eligibility for retreatment, and that these differed for the two treatment regimens. In the analyses on rituximab treatment reported here, a proportion of patients were shown to exhibit improvement following additional rituximab courses despite initially meeting criteria for non-response, an observation reported to varying degrees in previous studies [15, 16]. In this study, patients classed as EULAR non-responders at Week 24 did achieve decreases in DAS upon additional courses of rituximab treatment, although these decreases were more modest in comparison with those of EULAR responders at the same time point. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that continued therapy must be carefully considered in patients who show no evidence of therapeutic benefit within 24 weeks.

It is encouraging that there were no apparent safety concerns associated with the more frequent administration of rituximab in the TT group. Indeed, the rates of clinically relevant events, such as SIEs, were numerically lower in the TT population. However, such observations may not be surprising given the potential association with higher disease activity and greater risk of infection [22].

In contrast, the rates of overall AEs and overall infections appeared to be higher in the TT group. However, it is of interest that the rates of these events in the TT group are generally comparable with those previously reported in the overall rituximab clinical trial programme. Specifically, the rates of all AEs and all infections were 364.3 (95% CI 347.1, 382.4) and 111.9 (95% CI 102.5, 122.1) per 100 patient-years, respectively, in the TT population and 359.6 (95% CI 354.4, 364.9) and 97.7 (95% CI 95.0, 100.5) per 100 patient-years within all clinical trials [23]. Given that the rates of these events in the PRN group were 255.0 (95% CI 245.2, 265.2) and 69.7 (95% CI 64.6, 75.1) per 100 patient-years, respectively, it could be suggested that these events were uncharacteristically low in the PRN population rather than unusually high in the TT population.

The continued safety of the TT regimen, and the consequences of continual peripheral B-cell depletion induced by the TT approach over a longer observation period, will require further investigation. It should also be considered that, although both regimens were evaluated for efficacy over a 2-year period in the current study, the frequency of administration during this time was significantly greater in the TT regimen, with a greater potential for B-cell repopulation under the PRN regimen. However, based on the current findings, and given the improved efficacy, tighter control of disease and tolerable safety profile, the benefit : risk ratio of the TT strategy with rituximab appears favourable over the time period studied. However, it must be accepted that as RA is a life-long disease, this benefit : risk ratio could change in the long term.

The findings from this evaluation are consistent with data from the Belgian MabThera in RA (MIRA) registry, which also illustrated the benefits of a retreatment to target approach with rituximab [24]. In that study, retreatment was administered from Week 24 in patients with DAS-28-ESR ⩾3.2; that is, retreatment of patients no longer achieving the target of low disease activity rather than remission, which was the target in the current study. Retreatment with rituximab under these conditions also resulted in lower DAS-28-ESR values at the start of the second course compared with pre-rituximab values. However, it was observed that at the point when patients became eligible for retreatment (from Week 24 onwards), the mean DAS-28-ESR was greater than at earlier time points, indicating returning disease. Therefore, although the study supports the concept of treating to target, the tighter control of disease observed in the current study was possibly achieved by targeting a lower disease level (DAS-28-ESR <2.6 vs <3.2).

Although a target of DAS-28-ESR remission was used in the present study, other disease activity measures, particularly those that are easier to apply by the rheumatologist, such as the Simplified Disease Activity Index and the Clinical Disease Activity Index [25] or the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3; [26]), may be similarly effective. In contrast, as rituximab is a B-cell depleting agent, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that monitoring of B-cell levels may be instrumental in triggering retreatment, and indeed by using a high-sensitivity assay to identify poor B-cell depleters in non-responders suitable patients for retreatment can be identified [27]. However, using conventional B-cell analysis, no correlation between peripheral B cells and clinical response has been found [28], indicating that monitoring peripheral B-cell levels by such methods may not be of use as a determinant for retreatment with rituximab.

In summary, and while acknowledging the limitations of these evaluations, it can be concluded that retreatment with rituximab, based on 24-week evaluations and treatment to a target of DAS-28-ESR remission, leads to improved efficacy and tighter control of disease activity compared with a PRN regimen. Rituximab TT may be the preferable regimen for the treatment of patients with RA.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology Online.

Acknowledgements

Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech Inc. and Biogen Idec.

Funding: This work was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech Inc. and Biogen Idec.

Disclosure statement: N.B.G. has received research grants and consulting fees from Genentech. A.R.-R. has received honoraria and is a member of a speakers’ bureau for Roche. P.E. has undertaken clinical trials and provided expert advice for Roche, Abbott, Pfizer, MSD and BMS. U.M.-L. is a speaker for and advisor to Roche. H.T. is an employee of Roche. M.R. is an employee of and owns stock in Roche. P.J.M. receives consulting fees, speaker honoraria and research grants from Abbott, Amgen, Biogen Idec, BMS, Centocor, Crescendo, Genentech, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. J.R.C. has received honoraria, grant/research support and is a consultant for Roche/Genentech. S.W. is an employee of Roche.

References

- 1.Schoels M, Knevel R, Aletaha D, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:638–43. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Verstappen SM, Bijlsma JW. Tight control in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: efficacy and feasibility. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(Suppl. 3):iii56–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.078360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:263–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka E, Mannalithara A, Inoue E, et al. Efficient management of rheumatoid arthritis significantly reduces long-term functional disability. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1153–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.072751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3381–90. doi: 10.1002/art.21405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allaart CF, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BA. Aiming at low disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with initial combination therapy or initial monotherapy strategies: the BeSt study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(6 Suppl. 43):S-77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combe B, Landewe R, Lukas C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis: report of a task force of the European Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:34–45. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoels M, Aletaha D, Smolen JS, et al. Follow-up standards and treatment targets in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Results of a questionnaire at the EULAR 2008. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:575–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keystone E, Emery P, Peterfy CG, et al. Rituximab inhibits structural joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:216–21. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793–806. doi: 10.1002/art.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emery P, Deodhar A, Rigby WF, et al. Efficacy and safety of different doses and retreatment of rituximab: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial in patients who are biological naive with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate (Study Evaluating Rituximab's Efficacy in MTX iNadequate rEsponders (SERENE)) Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1629–35. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards JC, Szczepañski L, Szechiñski J, et al. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mease PJ, Cohen S, Gaylis NB, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with previous inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the SUNRISE Trial. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:917–27. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubbert-Roth A, Tak PP, Zerbini C, et al. Efficacy and safety of various repeat treatment dosing regimens of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a Phase III randomized study (MIRROR) Rheumatology. 2010;49:1683–93. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emery P, Fleischmann R, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, et al. The efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate treatment: Results of a phase IIB randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1390–400. doi: 10.1002/art.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keystone E, Fleischmann R, Emery P, et al. Safety and efficacy of additional courses of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label extension analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3896–908. doi: 10.1002/art.23059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furst DE, Kremer J, Strand V, Reed G, Greenberg J. The rate of infection adverse events (AEs) is increased as disease activity increases in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(Suppl. 9) Abstract 958. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Vollenhoven RF, Emery P, Bingham CO, III, et al. Longterm safety of patients receiving rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:558–67. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vander Cruyssen B, Westhovens R, Durez P, de Keyser F MIRA Study Group. The Belgian MIRA (MabThera in Rheumatoid Arthritis) Registry: Clues for the optimization of rituximab treatment strategies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(Suppl. 10) doi: 10.1186/ar3129. Abstract 993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1360–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.091454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pincus T, Swearingen CJ, Bergman MJ, et al. RAPID3 (Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data) on an MDHAQ (Multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire): agreement with DAS28 (Disease Activity Score) and CDAI (Clinical Disease Activity Index) activity categories, scored in five versus more than ninety seconds. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:181–9. doi: 10.1002/acr.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vital EM, Dass S, Rawstron AC, et al. Management of non-response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: predictors and outcome of retreatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1273–9. doi: 10.1002/art.27359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dass S, Rawstron AC, Vital EM, Henshaw K, McGonagle D, Emery P. Highly sensitive B cell analysis predicts response to rituximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2993–9. doi: 10.1002/art.23902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.