Summary

Normal human consciousness requires brainstem, basal forebrain, and diencephalic areas to support generalized arousal, as well as functioning thalamocortical networks to become aware of, and respond to environmental and internal stimuli. Injury to or disconnection of these interconnected systems, typically from cardiac arrest and traumatic brain injury, can result in disorders of consciousness, including coma, vegetative state, minimally conscious state, and akinetic mutism. Similar brain injuries can also result in loss of motor output out of proportion to consciousness, resulting in misdiagnoses of disorders of consciousness. We review pathology and imaging studies and derive mechanistic models for each of these conditions, to aid in the assessment and prognosis of individual patients. We further suggest how such models may guide the development of target-based treatment algorithms to enhance recovery of consciousness in many of these patient.

Keywords: consciousness, vegetative state, minimally conscious state, traumatic brain injury, arousal

Introduction

Disorders of consciousness encompass a wide range of syndromes where patients demonstrate a globally impaired ability to interact with the environment. We briefly review the subset of disorders of consciousness that result from permanent brain injury, such as ischemic stroke, global ischemia, and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Disorders of consciousness may also arise as functional (rather than structural) disturbances of consciousness, including generalized and complex partial seizures as well as metabolic and toxic delirium. These functional disturbances are not discussed here but have been recently reviewed by Posner and colleagues1.

We first review brain structures that support the normal conscious state in order to develop a framework for how their dysfunction can lead to disorders of consciousness. We then present a nosology of the different disorders of consciousness, including coma, vegetative state, the minimally conscious state, and akinetic mutism. We review the pathology and brain imaging data that give insight into the pathophysiology associated with each diagnostic category. Finally, we show that knowledge of the underlying mechanisms of the disorders can enhance our ability to prognosticate and promote the recovery from these devastating conditions.

Biological basis of consciousness: mechanisms of arousal and cerebral integrative function

A clinically relevant definition of consciousness

Normal human consciousness is defined as the presence of a wakeful arousal state and the awareness and motivation to respond to self and/or environmental events. In the intact brain, arousal is the overall level of responsiveness to environmental stimuli. Arousal has a physiological range from stage 3 non-REM sleep, where strong stimuli are required to elicit a response, to states of high vigilance, where subtle stimuli can be detected and acted upon2. While arousal is the global state of responsiveness, awareness is the brain’s ability to perceive specific environmental stimuli in different domains, including visual, somatosensory, auditory, and interoceptive (e.g. visceral and body position). The focal loss of awareness, such as language awareness in aphasia or spatial awareness in left-sided neglect, does not significantly impair awareness in other modalities. Motivation is the drive to act upon internal or external stimuli that have entered conscious awareness. In the next section, we describe the brain regions that support these three aspects of consciousness and show that they are not independent, but rather heavily interact with each other.

Underlying substrates of arousal and conscious awareness

The initial discovery that specific brain areas could drive overall cerebral activity appeared in the work of Moruzzi and Magoun3. These investigators proposed the existence of an ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) in the upper brainstem tegmentum (reticular formation) and central thalamus, which promoted widespread cortical activation4. Subsequent work has revealed that the ARAS is not a monolithic activating system, but rather is a collection of interdependent subcortical and brainstem areas that have specific roles in arousal and awareness5. The core areas for maintaining an awake state appear to be glutamatergic and cholinergic neurons in the dorsal tegmentum of the midbrain and pons6. These areas activate the central thalamus (primarily intralaminar nuclei) and basal forebrain. The central thalamus and basal forebrain subsequently activate the cortex through glutamatergic and cholinergic projections, respectively. In addition to supporting arousal, the basal forebrain is active during REM sleep, and the central thalamus plays a role in conscious awareness (see below).

Other brain regions are also involved in arousal, but have a more modulatory role, including nuclei in the upper brainstem that utilize norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters. These nuclei act upon the basal forebrain, thalamus, striatum, and cortex2,5. The hypothalamus is also involved in the sleep-wake transition7, and its histaminergic outputs help maintain the awake state. Overall, the large number of regions involved in arousal provides a redundancy, so that selective damage to one region, even if bilateral, only rarely results in permanent unconsciousness.

While the level of arousal reflects the overall state of activity in the brain, conscious awareness is a more dynamic and complex process involving a variety of cerebral networks at any one time. There are several competing theories as to how we become aware of environmental and internal stimuli, though it is widely thought to depend on interactions between the cortex and specific and non-specific (e.g., intralaminar) thalamic nuclei8-10.

Conscious awareness and arousal states also interact. Without arousal, there is no awareness, and in states of high arousal, awareness can be focused on one modality at the expense of others11. For example, animal models have been used to demonstrate that in addition to a core “generalized arousal”, there are also more specific forms of arousal, such as hunger, sexual behavior, and fear, which enhance responses to specific stimuli12,13. Conversely, awareness also influences arousal, such as the abrupt increase in arousal when an alarm goes off.

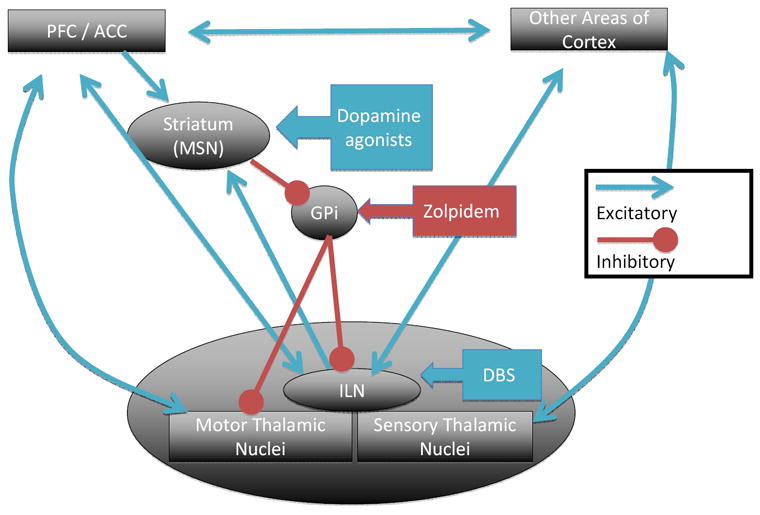

Stimuli are not acted upon as reflexes, but typically require motivation to enter conscious awareness through a process called intention, or goal-directed behavior14,15. Lesion and functional brain imaging studies demonstrate that goal-directed behavior is primarily driven by the medial frontal and anterior cingulate cortices16-18. These cortical regions are supported in producing goal-directed behavior by striato-pallidal-thalamic loops as well as the ventral tegmental area and periaqueductal gray of the brainstem19 (Figure 1). Of note, the arousal systems discussed previously also act directly on the goal-directed behavior network primarily through innervation of the striatum and frontal cortex18,20.

Figure 1.

A simplified model of a network that drives goal-directed behavior together with targets for specific interventions. Abbreviations: ACC- anterior cingulate cortex; GPi – globus pallidus pars interna; ILN – intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus; MSN – medium spiny neurons; PFC – prefrontal cortex. Blue arrows represent glutamatergic synapses and red represent GABAergic synapses unless otherwise noted.

In summary, studies to date indicate that the normal conscious state includes volition, processing of sensory information, and a generalized level of arousal. As will be discussed below, brain injury can produce disorders of consciousness from injury at any of these levels.

Nosology and pathophysiology of disorders of consciousness

The disorders of consciousness discussed in this manuscript are syndromes that are behaviorally defined, and each is thought to reflect a specific pathophysiological model (Table 1). However, the models are imprecise and do not apply in every case. As such, we will begin with an overview of the behavioral assessment of level of consciousness, followed by more detailed descriptions for each syndrome. Pathology and imaging data will be used to support mechanistic models underlying each behavioral syndrome.

Table 1.

Summary of behavioral features and pathophysiologies of disorders of consciousness syndromes from permanent brain injury.

| Syndrome | Behavioral Description | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| Coma | Eyes closed, immobile, or reflex movements. | Global dysfunction of corticothalamic loops from diffuse cellular dysfunction, disconnection, or loss of upper brainstem arousal tone. If entire brain or brainstem is permanently non-functional, then diagnosis is Brain Death rather than coma. |

| Vegetative State | Alternating eyes closed / eyes open states, reflex movements | Same as coma, except that it implies some functioning of upper brainstem. |

| Minimally Conscious State | Low-level and typically intermittent interaction with environment. Emergence from MCS defined as recovery of functional object use or consistent communication. | Diverse, but typically diffuse injury to white matter and / or thalamus. Varying degrees of cortical injury. |

| Akinetic Mutism | Severe form has eye tracking only (fits within MCS), while milder forms have decreased initiation of goal-directed behavior though response to external commands | Dysfunction of prefrontal cortex or its subcortical connections (striatum, globus pallidus, or central thalamus) or to white matter connecting these areas. |

| Locked-In-State* | Complete or almost complete loss of motor output resulting in the appearance of a disorder of consciousness. | Classically the loss of corticospinal tract in ventral pons, but can also be from diffuse white matter injury in the setting of trauma. |

Not a disorder of consciousness

General concepts in the assessment of consciousness

The determination of level of consciousness at the bedside is primarily a judgment of responsiveness across multiple sensory modalities (e.g. vision, somatosensation, and auditory) and cognitive domains (e.g. language and learned movements). The lowest level of behavior to document is to determine if eye opening is spontaneous or requires stimulation (e.g. loud sounds or noxious touch). Higher-level behaviors include responses that are contingent upon sensory stimuli. These range from eyes tracking a mirror and withdrawal from painful touch, all the way to accurately following commands and using objects (e.g. a comb or toothbrush) (REF Giacino CRS paper). The level of effort required to alert the patient and their speed of response should also be noted, since these observations guide subjective and objective assessments of arousal. Inaccuracy in specific cognitive domains (e.g. aphasia and apraxia) reflects focal impairments in awareness, rather than global disorders of consciousness.

One caveat to behavioral testing of arousal is that ALL of the patient responses require a capacity for motor output and adequate arousal. Patients with functional or structural interruption of motor systems at any level may not be able to follow the commands, despite full comprehension and intention. Those with minimal residual ability to communicate (e.g. eye blinks), but who generally have intact consciousness, are deemed to be in the locked-in-state (LIS)1. There are also patients with both impaired motor output and diffuse brain injury, which contributes to a high misdiagnosis rate of disorders of consciousness21,22. To ensure the accurate diagnosis in patients with a diffuse brain injury, it is essential to examine patients at maximal levels of arousal. To achieve this situation, one can use techniques such as deep tendon massage or postural repositioning23. Patients should also be examined at multiple time points or videotaped by family to capture periods of high alertness.

Coma and vegetative state represent loss of corticothalamic function

The most common disorder of consciousness that immediately follows a severe brain injury is coma. Coma is a state that is characterized by eyes-closed unresponsiveness: comatose patients fail to respond to even the most vigorous stimulation1. When given noxious stimulation, patients may not move at all, or may display stereotyped/reflexive movements only. Coma pathophysiology is generally the same as vegetative state (discussed below), except that some patients have loss of some or all brainstem function. For those with loss of all brainstem and cerebral function, the diagnosis is brain death. Coma prognosis is complex and depends on the etiology, severity of injury, and typically multiple medical factors that led to the initial injury1. Brain death does not have a prognosis, since it is simply equivalent to death.

If patients survive coma, they either recover consciousness over days, or transition to the vegetative state (VS) within 10 to 30 days post-injury. VS is a behaviorally-defined state, similar to coma, where patients show no evidence of self or environmental awareness24. It is also similar to coma as these patients can have spontaneous, or stimulus-induced, stereotyped movements, and may retain brainstem regulation of visceral autonomic function that would suggest that the lower brainstem is intact. The only behaviorally salient difference from coma is that these patients cycle daily through periods of eyes open and eyes closed. This does not imply that VS patients have normal sleep wake cycles; rather, their EEGs typically display a monotonous slow pattern regardless of whether the eyes are open or closed, or only have fragmented components of normal electrographic sleep-wake phenomenology25,26. The periods of eye opening reflect only a crude arousal pattern that involves upper brainstem nuclei.

VS may represent a transitional state on the way to recovery of consciousness or could be a chronic condition in cases of more severe brain injuries. Persistent vegetative state (PVS)24 is a term used for patients who have remained in VS for an arbitrarily defined duration of 30 days27. Another commonly used term is permanent vegetative state, which is applied to patients in VS after global ischemia for three months or TBI for one year27. Permanent VS is more of a prognosis than a diagnosis, as these time durations reflect only a reduced probability of recovery. As such, we prefer to define patients in persistent VS simply by their etiology and duration, and avoid using absolute terms such as “permanent.”

There are three main pathology findings in patients with prolonged VS from structural injury. The most common is diffuse cortical and thalamic cell loss, which typically occurs in the setting of global ischemia due to cardiac arrest28. The second is widespread damage to long axons, known as diffuse axonal injury (DAI), which typically occurs from TBI29. DAI has been shown in animal models to occur due to rapid acceleration-deceleration injury of the axons, and sometimes in conjunction with delayed axonal disconnections30 The third and least-common pattern of injury is extensive damage to the upper brainstem and thalamus, which usually occurs due to basilar artery stroke31,32. The common link between these three injury types and VS is the loss of corticothalamic function, either from cell death, disconnection, or loss of brainstem drive.

In vivo imaging studies further support the model of VS that represents diffuse corticothalamic dysfunction. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET is a measure of energy consumption, and in the brain it primarily represents the neuronal firing rate at the synapse33. Patients in PVS have been shown to have global metabolic rates reduced by 50% or more compared to healthy controls34. In general, metabolic rates exhibit less reduction in the brainstem and more reduction in the cortex and subcortical nuclei, with the most consistent reduction occurring in the medial parietal and frontal areas35. Comparable reductions in cerebral metabolic rate have been identified during generalized anesthesia36,37 and slow wave sleep in healthy controls38,39.

To examine corticothalamic functioning more directly, investigators have used H2 15O – PET, fMRI, and event-related potential analysis to measure brain responses to sensory inputs40. Studies using simple and complex auditory stimuli41-43 and noxious stimuli44, have demonstrated a pattern of activation of brainstem and primary sensory cortical regions in some VS patients, without the activation of higher order sensory or association areas. These results suggest that patients with VS may have some residual thalamocortical activity, but do not possess enough to produce global integrative function that is required for conscious awareness.

The above-mentioned imaging tools have also been used to provide insight into an ambiguous area between VS and consciousness. Schiff and colleagues45 described three patients who demonstrated complex motor behaviors but who were still considered to be in VS. All were found to have an overall low resting metabolism (20-50% of normal by FDG PET), yet had residual islands of cortical and subcortical higher metabolism in areas consistent with their behaviors. Importantly, in all subjects, these brain structures showed marked abnormalities at the level of response to simple sensory stimuli, as measured by magnetoencephalography, which demonstrated a loss of the integrity of even early cortical processing. These patients, similar to those studied by Laureys and colleagues43,46, revealed that some preservation of basic corticothalamic processing may co-exist with behavioral unconsciousness and do not contravene a clinical diagnosis of vegetative state.

The minimally conscious state represents a low level of residual corticothalamic integrity or an inability to maintain cerebral integrative function

The next level of recovery on the continuum from VS to full consciousness is the minimally conscious state (MCS). The Aspen Neurobehavioral Workgroup defined MCS in 2002 as “a condition of severely altered consciousness in which minimal but definite behavioral evidence of self or environmental awareness is demonstrated”47. This condition has been operationally defined by a set of behavioral tests known as the JFK Coma Recovery Scale Revised (CRS-R)48, which are discussed by Hirschberg and Giacino (this volume). MCS includes a more heterogeneous group of patients than VS, since the operational definition allows for a wide range of behaviors, while VS only includes reflexive movements. In MCS, low-end behaviors include visual tracking to a mirror, localization of noxious touch, and inaccurate verbalization, while high-end behaviors include consistent movement to command and correctly choosing between two objects. Patients with only low-end behaviors can be difficult to differentiate from VS, since these behaviors may be subtle and infrequent21,49,50. This differentiation is essential because patients in MCS have significantly better prognoses for recovery than those in VS51,52.

The pathology and anatomic imaging literature have revealed that MCS is typically associated with similar injury patterns as VS, but with sufficient surviving neurons and connectivity between cortex, thalamus, and brainstem arousal centers, which support some level of behavioral responsiveness53,54. In the setting of TBI, one study found that across the continuum of VS to MCS to full consciousness, patients were less likely to have severe DAI and more likely to have focal brain injuries, such as hematomas and contusions53. Notably, these authors reported overlap in pathological findings across all levels of consciousness, which demonstrated that current anatomical methods cannot completely account for the variances in behavior.

Functional imaging (fMRI and H2 15O PET) and neurophysiological methods have proven to be more sensitive than anatomical methods in distinguishing patients in VS from those in MCS because they measure corticothalamic function. For example, when presented with sensory stimuli, MCS patients activate higher-order association cortices like healthy controls, while VS patients at most activate primary sensory cortices55,56. However, when compared to healthy controls, MCS patients typically require a higher level of arousal (i.e. more alerting stimulus) to produce similar patterns of activation41. This requirement for a higher level of arousal is consistent with behavioral data, which shows that these patients fluctuate in their level of responsiveness57, and suggests an underlying inability to maintain cerebral integrative functioning.

Akinetic mutism and related syndromes are disorders of goal-directed behavior

Akinetic mutism, in its originally described form, fits in the category of MCS58, though milder variants, including abulia59,60, are categorized as fully conscious61. Patients with these conditions have intact arousal and often the appearance of vigilance, but have severe poverty of movement despite a lack of damage to motor systems. Severe cases can only be distinguished from VS by the preservation of visual tracking through smooth pursuit eye movements. The underlying pathology in most cases is injury to bilateral medial frontal lobes and anterior cingulate cortex from a mass lesion or anterior cerebral artery infarct. These syndromes can also arise from bilateral injury to the basal ganglia62,63, dorsal and central thalamus, or midbrain64, since these areas are tightly integrated with the frontal lobes in the generation of goal-directed behavior. As discussed below, the circuits involving these areas play a significant role in recovery of consciousness from a wide range of injuries.

Patients with severely damaged motor system may be widely miscategorized

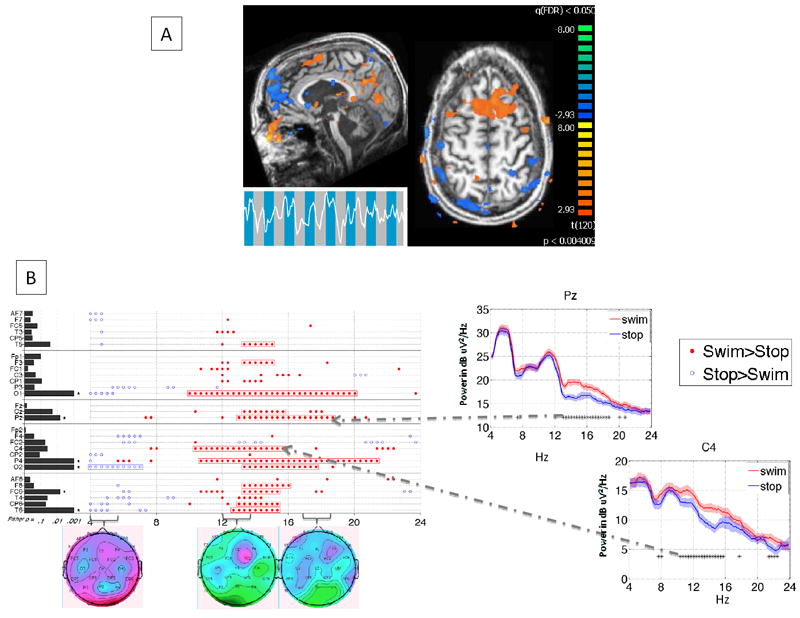

Functional brain imaging studies have led to a new, but currently undefined, category of disordered consciousness: patients who are behaviorally VS or MCS, yet demonstrate imaging evidence of high-level cognitive processes, including command following and, in two instances, communication65-67. These studies used fMRI (though EEG may also be used68) to reveal changes in cortical activity when patients are asked to imagine a motor performance or spatial navigation task (see Figure 2 for example results). The most striking example of covert conscious function came from a patient who initially fulfilled the behavioral criteria for VS, but was able to answer five out of six autobiographical questions correctly using mental imagery of tennis playing as a “yes” response and walking around his house as a “no” response66. Only a few such patients have been identified, as there are no obvious historical or anatomical imaging markers to predict covert consciousness. Furthermore, the assessments currently used require levels of memory and attention not present in even some fully conscious subjects67. The clinical implications of these findings are also not clear, since it is not yet possible to turn these fMRI or EEG paradigms into a bedside communication device. Moreover, it is not known if the ability to follow commands through fMRI predicts an emergence to full consciousness. However, once these measurements are obtained, it is clear that the patients have interacted with their environment, thereby placing them in a vague category between high level MCS and LIS.

Figure 2.

Non-invasive imaging evidence of command-following in a patient with severe brain injury who was behaviorally locked-in. A. FMRI demonstrating increased activity (orange) in supplementary motor and other cortical areas when the patient was asked to imagine swimming versus a resting baseline (Adapted from 67). B. Spectral analysis of EEG in the same subject performing the imagination of the swimming task at a different time. Example power spectra for 2 channels are on the right; the image on the left summarizes significant spectral changes across all channels and frequencies tested. Headmaps below summarize amplitude of power change across all channels at the frequencies listed directly above (Adapted from 68).

Mechanistic considerations in the prognosis and treatment of patients with disorders of consciousness

Prognosis from disorders of consciousness

The pathophysiologies described above help to explain the mechanisms by which some patients recover and why others do not, and give an interpretive framework for the successes of specific interventions in improving arousal. In brief, the three types of pathophysiologies linked to disorders of consciousness from permanent brain injury discussed above are: (i) loss of cortical and thalamic neurons from global ischemia, (ii) DAI in the setting of rapid acceleration / deceleration that leads to the disconnection of corticothalamic loops, and (iii) damage to the upper brainstem and central thalamic neurons leading to loss of arousal tone for corticothalamic loops. In addition, dysfunction of medial frontal systems from any of these three mechanisms, as well as others, may result in MCS and globally impaired levels of function near the operational criteria for MCS (i.e. akinetic mutism).

Global ischemia generally has the worst prognosis of the injury types discussed because of the marked sensitivity of cortical and thalamic neurons to hypoxia and ischemia28. In this setting, the key question is typically the prediction of recovery in order to avoid futile attempts at sustaining life in patients who are often otherwise quite ill69. Previously, this declaration could be made purely on clinical grounds within three days after the injury70, but with the recent addition of therapeutic hypothermia71,72, these criteria no longer apply73 and new criteria need to be developed. Prognosis is difficult, which is most likely because the neurons spared by hypothermia remain functionally impaired for long time periods, leading to a later demonstration of recovery. As a result, new prognostic algorithms need to be developed, which will likely require more time post-injury as well as new imaging and electrophysiological techniques. If patients survive and transition to MCS, treatment strategies are similar to those discussed below.

Patients with DAI presenting with coma have a wide range of outcomes, from prolonged VS to independent function27,69. The time course of recovery is also variable, ranging from days to years. Interestingly, one patient regained full consciousness and language after 19 years in MCS74. There are no reliable predictors of recovery in this population, though rough guidelines suggest that patients in MCS have a higher likelihood of recovery than those in VS, especially if MCS occurs within the first year51,52. This is a better prognosis than patients with global ischemia, where recovery to independence is exceedingly rare once the patient remains in VS for three months. The mechanism by which the brain recovers from DAI is still not clear75. Possible contributors to recovery include the regrowth of corticothalamic axons74,76,77 and the remapping of intracortical connections to maximize spared pathways78.

In cases of upper brainstem and central thalamic injury, recovery of function depends upon the ability of the remaining arousal centers to restore patterned corticothalamic activity. If return of consciousness occurs, patients may be left with severe cognitive deficits, depending on the degree of thalamic injury79. Similar to DAI, there are a wide range of reported outcomes, but anatomic and functional imaging techniques do not allow us to predict the potential for recovery in most cases.

Treatment strategies for patients with disorders of consciousness

Akinetic mutism offers a model for approaches that improve the level of consciousness (Figure 1). In akinetic mutism, the injury to the cortico-striato-pallidal-thalamo-cortical circuit involving the medial frontal lobe can produce dysfunction as severe as patients with much more widespread injury58,61. Increasing function of this circuit through medications or brain electrical stimulation can drive activity widely through the cerebrum80. For example, dopaminergic agents (e.g., amantadine, levodopa, bromocriptine, or apomorphine), which enhance striatal background activity, have been shown to raise the level of consciousness and improve recovery rates in patients with a variety of severe brain injuries (reviewed in Hirschberg and Giacino (this volume)). Zolpidem, an agonist of a subset of GABAA receptors, has also been demonstrated to dramatically improve consciousness in patients with diffuse brain injury81,82. The mechanism of action of zolpidem is thought to occur through cortical activation, both directly83 and indirectly, by inhibiting the globus pallidus interna from inhibiting thalamocortical firing84. Another successful approach through the same network, though only reported in a single patient, is the direct activation of the central thalamus via deep brain stimulation (DBS)85,86.

There are no clear guidelines for medical management to attempt to speed recovery of consciousness, since almost all data are from case series. Accordingly, we offer some approaches that have been proven to be successful in our experience. For a medically stable patient with a disorder of consciousness, the first goal is to rule out potential inhibitors of recovery. This includes undiagnosed seizure disorders, particularly because they can be difficult to detect behaviorally in patients with impaired motor output. Medications can also be culprits in worsening arousal, especially those with anticholinergic, antihistaminergic, barbiturate, and benzodiazepine properties as well as some antiepileptic and antispasticity agents87.

To promote recovery of consciousness, we typically recommend amantadine 200-400 mg split between early morning and early afternoon doses. Amantadine has a relatively benign safety profile and is the only medication tested to date in patients in VS and MCS in a well-powered, randomized, double-blind clinical trial88, though the results have not yet been published. An SSRI may also be added, based on animal model89 and clinical trial90 evidence for enhancing plasticity, though there is no strong evidence in patients with disorders of consciousness. Zolpidem can be given as 5 or 10 mg, with a response expected within one hour, though only rarely91. Zolpidem is apparently safe, though there is no long-term data and the potential for habituation exists. Medications should be trialed individually, with a gradual titration of dose. Patients should have well-documented, formal exams using the CRS-R prior to and following initiation and dose changes, and any side effects should be noted. In addition, physical, occupational, and speech therapy should be used when appropriate, including daily joint stretching to avoid contractures, which can severely limit movement when the motor system recovers.

Concluding remarks

As Fins has argued against, the approach to a patient with a chronic disorder of consciousness is often a nihilistic one, as if the loss of function is invariably permanent and there is nothing more to be gained from diagnostic testing and treatment92. We agree that these patients deserve a more systematic approach to their assessment, prognosis and treatment. The evidence described in this review shows that these conditions include a wide range of pathologies, etiologies, prognoses, and proven treatments. Diagnostic testing can already be used to determine the degree of injury and suggest residual capacity for cognitive function. Future work will allow us to use imaging modalities to predict recovery and develop tools to communicate with those who have lost all motor function.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by NIH-NICHD 51912, the James S McDonnell Foundation. AMG is supported by grant KL2RR024997 of the Clinical & Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, Plum F. Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma. 4. Oxford University Press; USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steriade MM, McCarley RW. Brain Control of Wakefulness and Sleep. 2. Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moruzzi G, Magoun HW. Brain stem reticular formation and activation of the EEG. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1949;1(4):455–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magoun HW. The Waking Brain. CHARLES C THOMAS PUBLISHER; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parvizi J, Damasio A. Consciousness and the brainstem. Cognition. 2001;79(1-2):135–160. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steriade M, Glenn LL. Neocortical and caudate projections of intralaminar thalamic neurons and their synaptic excitation from midbrain reticular core. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48(2):352–371. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mignot E, Taheri S, Nishino S. Sleeping with the hypothalamus: emerging therapeutic targets for sleep disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(Suppl):1071–1075. doi: 10.1038/nn944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llinás R, Ribary U, Contreras D, Pedroarena C. The neuronal basis for consciousness. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353(1377):1841–1849. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones EG. Thalamic circuitry and thalamocortical synchrony. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B, Biol Sci. 2002;357(1428):1659–1673. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tononi G, Edelman GM. Consciousness and complexity. Science. 1998;282(5395):1846–1851. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broadbent DE. Perception and communication. Pergamon Press; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garey J, Goodwillie A, Frohlich J, et al. Genetic contributions to generalized arousal of brain and behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(19):11019–11022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633773100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaff D. Brain Arousal and Information Theory: Neural and Genetic Mechanisms. 1. Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Searle JR. Intentionality, an essay in the philosophy of mind. Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brentano F. Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint. 2. Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frith CD, Friston K, Liddle PF, Frackowiak RSJ. Willed Action and the Prefrontal Cortex in Man: A Study with PET. Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 1991;244(1311):241–246. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paus T, Koski L, Caramanos Z, Westbury C. Regional differences in the effects of task difficulty and motor output on blood flow response in the human anterior cingulate cortex: a review of 107 PET activation studies. Neuroreport. 1998;9(9):R37–47. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paus T, Zatorre RJ, Hofle N, et al. Time-Related Changes in Neural Systems Underlying Attention and Arousal During the Performance of an Auditory Vigilance Task. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9(3):392–408. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. 1. Oxford University Press; USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinomura S, Larsson J, Gulyás B, Roland PE. Activation by Attention of the Human Reticular Formation and Thalamic Intralaminar Nuclei. Science. 1996;271(5248):512–515. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnakers C, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Giacino J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: Clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment. BMC Neurology. 2009;9(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smart CM, Giacino JT, Cullen T, et al. A case of locked-in syndrome complicated by central deafness. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(8):448–453. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott L, Coleman M, Shiel A, et al. Effect of posture on levels of arousal and awareness in vegetative and minimally conscious state patients: a preliminary investigation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2005;76(2):298–299. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.047357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jennett B, Plum F. Persistent vegetative state after brain damage. A syndrome in search of a name. Lancet. 1972;1(7753):734–737. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)90242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekinschtein T, Cologan V, Dahmen B, Golombek D. You are only coming through in waves: wakefulness variability and assessment in patients with impaired consciousness. Prog Brain Res. 2009;177:171–189. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17712-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobylarz EJ, Schiff ND. Neurophysiological correlates of persistent vegetative and minimally conscious states. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2005;15(3-4):323–332. doi: 10.1080/09602010443000605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Multi-Society Task Force on PVS. Medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(21):1499–1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405263302107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams JH, Graham DI, Jennett B. The neuropathology of the vegetative state after an acute brain insult. Brain. 2000;123(7):1327–1338. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams JH, Graham DI, Murray LS, Scott G. Diffuse axonal injury due to nonmissile head injury in humans: an analysis of 45 cases. Ann Neurol. 1982;12(6):557–563. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gennarelli TA, Thibault LE, Adams JH, et al. Diffuse axonal injury and traumatic coma in the primate. Ann Neurol. 1982;12(6):564–574. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingvar DH, Sourander P. Destruction of the reticular core of the brain stem. A pathoanatomical follow-up of a case of coma of three years’ duration. Arch Neurol. 1970;23(1):1–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480250005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castaigne P, Lhermitte F, Buge A, et al. Paramedian thalamic and midbrain infarct: clinical and neuropathological study. Ann Neurol. 1981;10(2):127–148. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eidelberg D, Moeller JR, Kazumata K, et al. Metabolic correlates of pallidal neuronal activity in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1997;120(8):1315–1324. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.8.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy DE, Sidtis JJ, Rottenberg DA, et al. Differences in cerebral blood flow and glucose utilization in vegetative versus locked-in patients. Ann Neurol. 1987;22(6):673–682. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laureys S, Goldman S, Phillips C, et al. Impaired Effective Cortical Connectivity in Vegetative State: Preliminary Investigation Using PET. NeuroImage. 1999;9(4):377–382. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blacklock JB, Oldfield EH, Di Chiro G, et al. Effect of barbiturate coma on glucose utilization in normal brain versus gliomas. Positron emission tomography studies. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(1):71–75. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.1.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alkire MT, Haier RJ, Barker SJ, et al. Cerebral metabolism during propofol anesthesia in humans studied with positron emission tomography. Anesthesiology. 1995;82(2):393–403. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199502000-00010. discussion 27A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maquet P, Dive D, Salmon E, et al. Cerebral glucose utilization during sleep-wake cycle in man determined by positron emission tomography and [18F] 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose method. Brain Res. 1990;513(1):136–143. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maquet P, Degueldre C, Delfiore G, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of human slow wave sleep. J Neurosci. 1997;17(8):2807–2812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02807.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruse D, Owen AM. Consciousness revealed: new insights into the vegetative and minimally conscious states. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(6):656–660. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833fd4e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiff ND, Rodriguez-Moreno D, Kamal A, et al. fMRI reveals large-scale network activation in minimally conscious patients. Neurology. 2005;64(3):514–523. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150883.10285.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bekinschtein TA, Dehaene S, Rohaut B, et al. Neural signature of the conscious processing of auditory regularities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(5):1672–1677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809667106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laureys S, Faymonville M-E, Degueldre C, et al. Auditory processing in the vegetative state. Brain. 2000;123(8):1589–1601. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.8.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laureys S, Faymonville ME, Peigneux P, et al. Cortical Processing of Noxious Somatosensory Stimuli in the Persistent Vegetative State. NeuroImage. 2002;17(2):732–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiff ND, Ribary U, Moreno DR, et al. Residual cerebral activity and behavioural fragments can remain in the persistently vegetative brain. Brain. 2002;125(6):1210–1234. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laureys S, Lemaire C, Maquet P, Phillips C, Franck G. Cerebral metabolism during vegetative state and after recovery to consciousness. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1999;67(1):121–122. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giacino JT, Ashwal S, Childs N, et al. The minimally conscious state: definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2002;58(3):349–353. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giacino JT, Kalmar K, Whyte J. The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: Measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2004;85(12):2020–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrews K, Murphy L, Munday R, Littlewood C. Misdiagnosis of the vegetative state: retrospective study in a rehabilitation unit. BMJ. 1996;313(7048):13–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanhaudenhuyse A, Schnakers C, Brédart S, Laureys S. Assessment of visual pursuit in post-comatose states: use a mirror. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2008;79(2):223. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.121624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Estraneo A, Moretta P, Loreto V, et al. Late recovery after traumatic, anoxic, or hemorrhagic long-lasting vegetative state. Neurology. 2010;75(3):239–245. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luauté J, Maucort-Boulch D, Tell L, et al. Long-term outcomes of chronic minimally conscious and vegetative states. Neurology. 2010;75(3):246–252. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jennett B, Adams JH, Murray LS, Graham DI. Neuropathology in vegetative and severely disabled patients after head injury. Neurology. 2001;56(4):486–490. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kampfl A, Schmutzhard E, Franz G, et al. Prediction of recovery from post-traumatic vegetative state with cerebral magnetic-resonance imaging. The Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1763–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boly M, Faymonville M-E, Peigneux P, et al. Auditory Processing in Severely Brain Injured Patients: Differences Between the Minimally Conscious State and the Persistent Vegetative State. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(2):233–238. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bekinschtein T, Niklison J, Sigman L, et al. Emotion processing in the minimally conscious state. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2004;75(5):788. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hart T, Whyte J, Millis S, et al. Dimensions of Disordered Attention in Traumatic Brain Injury: Further Validation of the Moss Attention Rating Scale. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2006;87(5):647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cairns H, Oldfield RC, Pennybacker JB, Whitteridge D. Akinetic mutism with an epidermoid cyst of the 3rd ventricle. Brain. 1941;64(4):273–290. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher CM. Honored guest presentation: abulia minor vs. agitated behavior. Clin Neurosurg. 1983;31:9–31. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/31.cn_suppl_1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stuss DT, Alexander MP. Is there a dysexecutive syndrome? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362(1481):901–915. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schiff ND, Plum F. The role of arousal and “gating” systems in the neurology of impaired consciousness. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;17(5):438–452. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200009000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhatia KP, Marsden CD. The behavioural and motor consequences of focal lesions of the basal ganglia in man. Brain. 1994;117(4):859–876. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mega MS, Cohenour RC. Akinetic mutism: disconnection of frontal-subcortical circuits. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1997;10(4):254–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Segarra JM. Cerebral Vascular Disease and Behavior: The Syndrome of the Mesencephalic Artery (Basilar Artery Bifurcation) Arch Neurol. 1970;22(5):408–418. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480230026003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Owen AM, Coleman MR, Boly M, et al. Detecting Awareness in the Vegetative State. Science. 2006;313(5792):1402. doi: 10.1126/science.1130197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Monti MM, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Coleman MR, et al. Willful Modulation of Brain Activity in Disorders of Consciousness. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):579–589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bardin JC, Fins JJ, Katz DI, et al. Dissociations between behavioural and functional magnetic resonance imaging-based evaluations of cognitive function after brain injury. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 3):769–782. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goldfine AM, Victor JD, Conte MM, Bardin JC, Schiff ND. Determination of awareness in patients with severe brain injury using EEG power spectral analysis. [July 17,2011];Clin Neurophysiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.03.022. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21514214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Jennett B. The vegetative state: medical facts, ethical and legal dilemmas. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levy DE, Caronna JJ, Singer BH, et al. Predicting outcome from hypoxic-ischemic coma. JAMA. 1985;253(10):1420–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.The Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rossetti AO, Oddo M, Logroscino G, Kaplan PW. Prognostication after cardiac arrest and hypothermia: a prospective study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):301–307. doi: 10.1002/ana.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Voss HU, Uluç AM, Dyke JP, et al. Possible axonal regrowth in late recovery from the minimally conscious state. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):2005–2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI27021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Povlishock JT, Katz DI. Update of neuropathology and neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20(1):76–94. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bendlin BB, Ries ML, Lazar M, et al. Longitudinal changes in patients with traumatic brain injury assessed with diffusion-tensor and volumetric imaging. NeuroImage. 2008;42(2):503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sidaros A, Engberg AW, Sidaros K, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging during recovery from severe traumatic brain injury and relation to clinical outcome: a longitudinal study. Brain. 2008;131(2):559–572. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dancause N, Barbay S, Frost SB, et al. Extensive cortical rewiring after brain injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25(44):10167–10179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3256-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katz DI, Alexander MP, Mandell AM. Dementia Following Strokes in the Mesencephalon and Diencephalon. Arch Neurol. 1987;44(11):1127–1133. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1987.00520230017007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schiff ND. Recovery of consciousness after brain injury: a mesocircuit hypothesis. Trends in Neurosciences. 2010;33(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clauss RP, van der Merwe CE, Nel HW. Arousal from a semi-comatose state on zolpidem. S Afr Med J. 2001;91(10):788–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brefel-Courbon C, Payoux P, Ory F, et al. Clinical and imaging evidence of zolpidem effect in hypoxic encephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(1):102–105. doi: 10.1002/ana.21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCarthy MM, Brown EN, Kopell N. Potential network mechanisms mediating electroencephalographic beta rhythm changes during propofol-induced paradoxical excitation. J Neurosci. 2008;28(50):13488–13504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3536-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schiff ND, Posner JB. Another “Awakenings”. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(1):5–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schiff ND, Giacino JT, Kalmar K, et al. Behavioural improvements with thalamic stimulation after severe traumatic brain injury. Nature. 2007;448(7153):600–603. doi: 10.1038/nature06041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schiff ND. Central thalamic deep-brain stimulation in the severely injured brain: rationale and proposed mechanisms of action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1157:101–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.04123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goldstein LB. Common drugs may influence motor recovery after stroke. The Sygen In Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Neurology. 1995;45(5):865–871. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meythaler JM, Brunner RC, Johnson A, Novack TA. Amantadine to improve neurorecovery in traumatic brain injury-associated diffuse axonal injury: a pilot double-blind randomized trial. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2002;17(4):300–313. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vetencourt JFM, Sale A, Viegi A, et al. The Antidepressant Fluoxetine Restores Plasticity in the Adult Visual Cortex. Science. 2008;320(5874):385–388. doi: 10.1126/science.1150516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chollet F, Tardy J, Albucher J-F, et al. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2011;10(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Whyte J, Myers R. Incidence of clinically significant responses to zolpidem among patients with disorders of consciousness: a preliminary placebo controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(5):410–418. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181a0e3a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fins JJ. Constructing an ethical stereotaxy for severe brain injury: balancing risks, benefits and access. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(4):323–327. doi: 10.1038/nrn1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]