Abstract

This study had two purposes. The first purpose was to assess the prevalence as well as the stability of reliance on social security disability income (SSDI) among patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). The second purpose was to detail the prevalence of aspects of adult competence reported by borderline patients who ever received disability payments and those who never received such payments. The disability status and other aspects of psychosocial functioning of 290 borderline inpatients and 72 axis II comparison subjects were assessed using a semi-structured interview at baseline and at each of the five subsequent two-year follow-up periods. Borderline patients were three times more likely to be receiving SSDI benefits than axis II comparison subjects over time, although the prevalence rate for both groups remained relatively stable. Forty percent of borderline patients on such payments at baseline were able to get off disability but 43% of these patients subsequently went back on SSDI. Additionally, 39% of borderline patients who were not on disability at baseline started to receive federal benefits for the first time. However, borderline patients on SSDI were not without psychosocial strengths. By the time of the 10-year follow-up, 55% had worked or gone to school at least 50% of the last two years, about 70% had a supportive relationship with at least one friend, and over 50% a good relationship with a romantic partner. The results of this study suggest that receiving SSDI benefits is both more common and more fluid over time for patients with BPD than previously known.

Clinical experience suggests that it is common for patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) to receive social security disability income (SSDI) – the U.S. federal program to support those with physician documented medical and/or psychiatric disabilities that prevent them from being able to support themselves financially. This link is important because receiving SSDI benefits adds to the cost of BPD as a public health problem. It also provides an indication of the degree of psychosocial dysfunction associated with BPD.

Despite the public health significance of this association, there have been a limited number of studies that have explored the relationship between BPD and disability benefits. First, there were three studies that looked at BPD in a sample of patients on SSDI disability. As early as 1977, Mikkelsen reported that 12% of individuals receiving psychiatric disability benefits suffered from “borderline personality organization.” He found borderline symptoms to be the third most common psychiatric diagnosis in disability candidates after “neurotic depression” (26%) and schizophrenia (22%). Later, in a study of 45 medical outpatients, Sansone, Hruschka, Vasudevan, and Miller (2003) noted that 72% of the participants with a history of medical disability payments versus 26% of the nondisabled participants met borderline criteria on at least one of the two self-report measures. Three years later with a larger sample, Sansone and colleagues found that the same self-report measures (of borderline psychopathology and self-harming behaviors) correlated with the length of time on psychiatric disability benefits in particular (as opposed to medical disability benefits) (Sansone, Butler, Dakroub, & Pole, 2006). These results were found to be significant for women only, perhaps due to the small number of male borderline patients studied.

There have also been five studies that have assessed the rates of disability payments in samples of criteria-defined borderline patients. In a cross-sectional study, Skodol et al. (2002) found that borderline patients were significantly more likely than depressed comparison subjects to report being disabled (36% vs. 18%).

The other four studies were longitudinal in nature. Modestin and Villiger (1989) studied two groups of former inpatients. It was found that borderline patients (22%) were not significantly more likely than comparison subjects with other personality disorders (12%) to report being on disability after a mean of 4½ years of follow-up. Sandell et al. (1993) found that 34% of borderline patients initially treated in a day hospital reported being on disability 3–10 years after their index admission.

Links, Heslegrave, and van Reekum (1998) found that 30% of former borderline inpatients were receiving disability pensions seven years after their index admission. These authors also found that borderline patients with persistent BPD were more likely to be receiving such a pension than those with remitted BPD (42.3% vs. 20.0%).

Finally, Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, Reich, and Silk (2005) found that the rates of borderline inpatients and axis II comparison subjects receiving disability payments increased slightly but significantly over six years of prospective follow-up but remained significantly higher among those with BPD (BPD [41% to 47%] vs. axis II comparison subjects [8% to 14%]). Additionally, 73% of borderline patients who had never experienced a remission supported themselves (at least in part) through disability payments as compared to 38% of borderline patients who had experienced a remission of their BPD.

The current study assesses the course of social security disability income in a sample of 290 borderline patients and 72 axis II comparison subjects using a semi-structured clinical interview over a period of 10 years. This study extends our prior study, described above, by adding an additional four years of prospective follow-up. It also considers not only prevalence rates but also time-to-no longer receiving these payments, time-to-receiving them again, and time-to-first receiving them for borderline patients who were self-supporting at baseline. Finally, it assesses the prevalence of three aspects of adult competence among those in two sub-groups of borderline patients: those who had ever received federal disability payments during the course of the study and those who had never received such payments during this time frame.

Methods

All subjects were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. Each patient was first screened to determine that he or she: 1) was between the ages of 18–35; 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; 3) had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures were explained, written informed consent was obtained. As part of a larger study (Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, & Silk, 2003), each patient then met with a masters-level interviewer blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough diagnostic assessment. Three semi-structured interviews were administered. These diagnostic interviews were: 1) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1992), 2) the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) (Zanarini, Gunderson, Frankenburg, & Chauncey, 1989), and 3) the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (DIPD-R) (Zanarini, Frankenburg, Chauncey, & Gunderson, 1987). The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of these measures have been found to be good-excellent (Zanarini & Frankenburg, 2001; Zanarini, Frankenburg, & Vujanovic, 2002).

Disability status was assessed at baseline using the Background Information Schedule (BIS) (Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, & Silk, 2004; Zanarini, et al., 2005). This semi-structured interview assesses the participant’s demographic data, pre-morbid functioning, and history of psychiatric treatment. Both the inter-rater and test-retest reliability of this interview have been found to be good-excellent (Zanarini et al., 2004; Zanarini, et al., 2005).

At each of the study’s five follow-up periods, informed consent was obtained and then disability status was assessed using the Revised Borderline Follow-up Interview (BFI-R), which is the follow-up analog to the BIS used at baseline. Both the follow-up inter-rater reliability (within one generation of raters) and follow-up longitudinal reliability (from one generation of raters to the next) have been found to be good-excellent (Zanarini et al., 2004; Zanarini et al., 2005).

To properly account for the correlation among repeated measures, generalized estimating equations (GEE), with diagnosis, time, and their interaction as main effects, were used in longitudinal analyses of prevalence data. These analyses modeled the log prevalence of disability with gender as an additional covariate (as borderline patients were significantly more likely than axis II comparison subjects to be female), yielding an adjusted relative risk ratio (RRR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for diagnosis and time. Similar analyses were conducted for three aspects of adult competence evidenced by borderline patients with and without a history of ever receiving SSDI (without gender as a covariate as the two sub-groups of borderline patients had about the same gender distribution). Alpha was set at 0.05, two-tailed.

Discrete survival analyses were used to assess time-to-remission, time-to-recurrence, and time-to-new onsets of receiving federal disability benefits. A remission was defined as occurring when a patient was receiving disability payments at baseline but was no longer receiving disability payments at one of the follow-up periods. A recurrence was defined as occurring when a patient was on disability at baseline, stopped receiving disability payments at a follow-up period, and then was back on disability at a later follow-up period. Finally, a new onset was defined as occurring when a patient was not receiving disability payments at baseline but then was receiving SSDI payments at a later period. All analyses were performed using Stata 9.2 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, 2007).

Results

Two hundred and ninety patients met both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for BPD and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for at least one nonborderline axis II disorder (and neither criteria set for BPD). Of these 72 comparison subjects, 4% met DSM-III-R criteria for an odd cluster personality disorder, 33% met DSM-III-R criteria for an anxious cluster personality disorder, 18% met DSM-III-R criteria for a non-borderline dramatic cluster personality disorder, and 53% met DSM-III-R criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified (which was operationally defined in the DIPD-R as meeting all but one of the required number of criteria for at least two of the 13 axis II disorders described in DSM-III-R).

Baseline demographic data have been reported before (Zanarini et al., 2003). Briefly, 77.1% (N=279) of the subjects were female and 87% (N=315) were white. The average age of the subjects was 27 years (SD=6.3), the mean socioeconomic status was 3.3 (SD=1.5), where 1=highest and 5=lowest (Hollingshead, 1957), and their mean GAF score was 39.8 (SD=7.8) indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood.

In terms of continuing participation, 90.1% (N=309) of surviving patients were re-interviewed at all five follow-up waves. More specifically, 91.5% of surviving borderline patients (249/272) and 84.5% of surviving axis II comparison subjects (60/71) were evaluated six times (baseline and five follow-up periods).

Table 1 details the prevalence of disability payments reported by borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects over 10 years of prospective follow-up. As can be seen, a significantly higher percentage of borderline patients than axis II comparison subjects reported receiving disability payments. When all subjects were considered together, the rate of disability payments did not change significantly over time.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Social Security Disability Reliance among Borderline Patients and Axis II Comparison Subjects over Ten Years of Prospective Follow-up

| Borderline Patients (%/N) |

Axis II Comparison Subjects (%/N) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (N=290) |

2 Yr FU (N=275) |

4 Yr FU (N=269) |

6 Yr FU (N=264) |

8 Yr FU (N=255) |

10 Yr FU (N=249) |

BL (N=72) |

2 Yr FU (N=67) |

4 Yr FU (N=64) |

6 Yr FU (N=63) |

8 Yr FU (N=61) |

10 Yr FU (N=60) |

RRR Diagnosisa Timeb Interactionc |

95% CI Diagnosis Time Interaction |

|

| SSDI Disability | 40.7 (N=118) | 50.2 (N=138) | 51.7 (N=139) | 46.6 (N=123) | 44.7 (N=114) | 44.2 (N=110) | 8.3 (N=6) | 16.4 (N=11) | 18.8 (N=12) | 14.3 (N=9) | 13.1 (N=8) | 18.3 (N=11) | 3.26 0.99 --- |

2.00, 5.31 0.88, 1.13 --- |

P-level result for diagnosis was < 0.001

P-level result for time was NS

P-level result for interaction was NS

The relative risk ratios (RRRs) for diagnosis and time in the table contain more fine-grained information. As can be seen, 41% of borderline patients (N=118) (and 8% of axis II comparison subjects [N=6]) were receiving SSDI at the time of their index admission. By the time of their 10-year follow-up, these prevalence rates increased to about 44% (N=110) and 18% (N=11) respectively. The RRR of 3.26 (95%CI 2.00, 5.31) indicates that borderline patients were about three times more likely to be receiving SSDI than axis II comparison subjects. The RRR of 0.99 (95%CI 0.88, 1.13) indicates that the chance of receiving SSDI over the course of the study for all subjects considered together remained relatively constant over time ([1−0.99] × 100=1% decline).

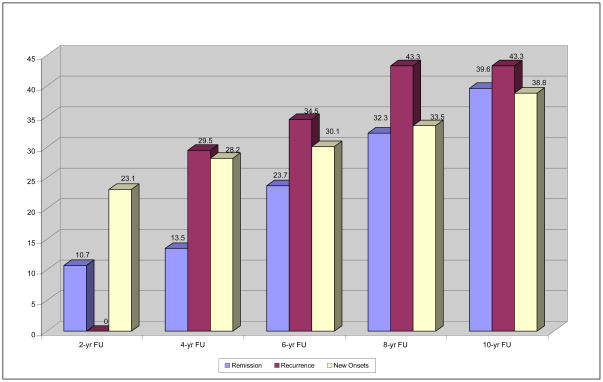

Figure 1 displays time-to-remission, recurrence, and new onsets of disability among borderline patients over 10-years of prospective follow-up. (As a result of the low number of axis II comparison subjects reporting being on disability, Figure 1 considers only borderline patients.)

Figure 1. Time to Remission, Recurrence, and New Onsets of Disability among Borderline Patients over Ten Years of Prospective Follow-up.

Note: Since a recurrence can only occur after a remission, there is no possibility of a recurrence occurring at the 2-year follow up. Even though recurrences are displayed in this figure at the 4, 6, 8, and 10-year follow-up periods, these recurrences are actually occurring 2, 4, 6, and 8 years after the remission.

As can be seen, the percentage of borderline patients who had a remission of being on disability by the time of the 10-year follow-up was about 40%. Of these borderline patients, 43% experienced a recurrence and once again were receiving payments. Of those borderline patients who had not reported being on disability at baseline, 39% experienced a new onset during the 10 years of follow-up.

By adding the number of borderline patients who were on disability at baseline (N= 118) to the number of borderline patients who experienced a new onset of receiving disability payments (N = 57), we found that 60.3% (118 + 57=175/290) of borderlines were ever on disability over the 10-year period.

Table 2 details the prevalence of three aspects of adult competence among borderline patients who were on disability at some point in the study (baseline and/or one of the study’s five follow-up periods) and borderline patients who were never on disability during the course of the study. As can be seen, the borderline patients who were ever on disability were significantly less likely than the borderline patients who were never on disability to have worked or gone to school at least 50% of the time, to have a good relationship with friends, and to have a good relationship with a romantic partner. As can also be seen, the percentage of both groups of borderline patients reporting each of these three aspects of adult psychosocial functioning increased significantly over time.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Aspects of Adult Competence among Borderline Patients Receiving and Not Receiving Disability Benefits over Course of Study

| Borderline Patients Ever on Disability (%/N) |

Borderline Patients Never on Disability (%/N) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (N=175) |

2 Yr FU (N=170) |

4 Yr FU (N=167) |

6 Yr FU (N=165) |

8 Yr FU (N=160) |

10 Yr FU (N=156) |

BL (N=115) |

2 Yr FU (N=105) |

4 Yr FU (N=102) |

6 Yr FU (N=99) |

8 Yr FU (N=95) |

10 Yr FU (N=93) |

RRR Disabilitya Timeb Interactionc |

95% CI Disability Time Interaction |

|

| Sustained Work/School History (50% or More of Time Period) | 51.4 (N=90) | 37.1 (N=63) | 56.3 (N=94) | 58.2 (N=96) | 58.1 (N=93) | 55.1 (N=86) | 96.5 (N=111) | 95.2 (N=100) | 97.1 (N=99) | 95.0 (N=94) | 94.7 (N=90) | 89.3 (N=83) | 0.49 0.94 1.34 |

0.43, 0.55 0.89, 0.99 1.13, 1.59 |

| Good Relationship with Friend(s) | 48.0 (N=84) | 59.4 (N=101) | 68.3 (N=114) | 66.1 (N=109) | 72.5 (N=116) | 70.5 (N=110) | 61.7 (N=71) | 69.5 (N=73) | 80.4 (N=82) | 83.8 (N=83) | 86.3 (N=82) | 87.1 (N=81) | 0.82 1.36 --- |

0.75, 0.90 1.25, 1.48 --- |

| Good Relationship with Partner | 29.1 (N=51) | 36.5 (N=62) | 37.1 (N=62) | 50.9 (N=84) | 51.3 (N=82) | 50.6 (N=79) | 40.0 (N=46) | 50.5 (N=53) | 58.8 (N=60) | 70.7 (N=70) | 68.4 (N=65 | 67.7 (N=63) | 0.75 1.63 --- |

0.64, 0.87 1.43, 1.87 --- |

P-level results for disability were < 0.001 for all three outcomes

P-level results for time were 0.021 for sustained work/school history, < 0.001 for good relationship with friend(s) and good relationship with partner

P-level results for interaction were 0.001 for sustained work/school history and NS for the other two variables

Only one of these three aspects of adult functioning was found to have a significant interaction between diagnosis and time. The relative risk ratio of 0.49 (95%CI 0.43, 0.55) indicates that borderline patients who were ever on disability were only half as likely as borderline patients who were never on disability to report having worked or gone to school for at least half of the two-year time period prior to baseline. The RRR of 0.94 (95%CI 0.89, 0.99) for time indicates that the relative change in these reports from baseline to 10-year follow-up resulted in an approximately 6% decline among borderline patients who were never on disability (1.0−0.94×100=6%). In contrast, the significant interaction between diagnosis and time of 1.34 (95%CI 1.13, 1.59) indicates a relative increase in these reports of about 26% for borderline patients who were ever on disability ([0.94×1.34 − 1.0]×100=26%).

Discussion

This study has four main findings. The first finding is that a significantly higher percentage of borderline patients than axis II comparison subjects were receiving SSDI benefits. In fact, borderline patients were more than four times as likely as axis II comparison subjects to be on SSDI disability at baseline and more than two times as likely to be receiving disability payments at the 10-year follow-up mark. The baseline and follow-up prevalence rates found in this study are consistent with those found in earlier studies (Skodol et al., 2002; Modestin et al., 1989; Sandell et al., 1993; Links et al., 1998; Zanarini et al., 2005). However, it is a new finding that about 60% of borderline patients received SSDI payments at some point in time during the study.

The second finding is that the prevalence of disability payments was relatively stable among borderline patients over the course of the study, with about 40% of borderline patients receiving such payments at baseline and at each of the five two-year follow-up periods—a rate that is 10 times the 4% of adults in Massachusetts aged 18–64 on SSDI for physical and/or psychiatric reasons (Social Security Administration, 2007). This new finding also suggests that about 60% of the borderline patients in the study were able to support themselves financially at each of the study’s six time periods.

The third finding is that a substantial percentage of borderline patients were not chronically receiving disability benefits. More specifically, about 40% of borderline patients receiving disability payments at baseline no longer needed such payments (i.e., experienced a remission). However, about 40% of those borderline patients experiencing this type of disability “remission” later went back on disability (i.e., experienced a recurrence). Further, about 40% of borderline patients who were not on disability at baseline later started to receive such payments (i.e., experienced a new onset). Taken together, these findings suggest that the relationship between BPD and disability payments is more fluid than previously known, with patients ending and beginning to receive such payments over time.

The fourth finding is that borderline patients on disability were not necessarily unable to function in most areas of their lives. Rather after ten years of follow-up, about 55% were able to work or go to school 50% of the time or more, about 70% have a good relationship with at least one friend, and about 50% have a good relationship with a romantic partner. These findings suggest that about half of borderline patients receiving federal disability benefits have some capacity to function vocationally. They also suggest that the social functioning of borderline patients on disability is better than their vocational functioning. However, it seems that intimate relationships with partners are harder to develop and maintain than relationships with friends.

It should also be noted that borderline patients who were never on disability benefits functioned substantially better in all areas. About 85% had a sustained vocational performance and a good relationship with at least one friend by the time of the nine-tenth years of follow-up. In addition, almost 70% had an emotionally sustaining relationship with a romantic partner during the fifth follow-up period.

The clinical implications of this study are complicated. In terms of vocational functioning, it may be that some borderline patients are so dysfunctional that helping them find a source of income is a reasonable thing to do for those treating them. It may also be that some borderline patients give up working, reduce their hours, or work under the table in order to receive the associated health insurance benefits (Medicare and Medicaid) that they need to continue their psychiatric (and medical) care.

In the former case, vocational counseling may be a useful form of adjunctive treatment and/or the focus of a primary therapy. In the latter case, a national health insurance system that separates vocational functioning from access to health care might well be a better model for borderline patients who can work but are discouraged from doing so under our current system.

In terms of social functioning, about a third of borderline patients who received SSDI during the course of the study did not have a good relationship with at least one friend during the fifth follow-up period and about half did not have a good relationship with a spouse or partner during this period. Looked at another way, about a third had either no friends or a conflicted relationship with one or more friends. In a similar vein, about half either did not have a partner or had a contentious relationship with one. Taken together, these results suggest that a focus in therapy on the interpersonal functioning of borderline patients receiving disability benefits would be useful. While this seems obvious, none of the four main forms of therapy for BPD have been shown to be effective in improving interpersonal functioning—either in terms of forming new relationships or developing less contentious ones (Gunderson & Links, 2008).

This study has a number of limitations. The first is that all subjects were initially inpatients. It may be that borderline patients who have never been hospitalized are less likely to rely on SSDI. The second is that the subjects provided all of the information pertaining to SSDI. Whether they were accurate historians, were exaggerating their histories, or minimizing them is unknown. The third is that the majority of the sample was in treatment prior to their index admission and over time and thus, the results may not generalize to untreated subjects. More specifically, about 90% of those in both patient groups were in individual therapy and taking psychotropic medications at baseline and about 70% were participating in each of these outpatient modalities during each follow-up period (Zanarini et al., 2004).

In addition, we have no information as to the diagnosis that was used on the disability application forms. It could have been BPD, PTSD, major depression, etc. We also have no way of knowing if the disability payments were sought to give a patient a monthly income because it was believed that he or she could not work or if the payments were sought as a first-step in the process of obtaining Medicare insurance for treatment. Of course, the motivation might have been both to give someone a small but sustaining income (as well as access to low income housing and food stamps) and to obtain health insurance for continued psychiatric treatment.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIMH grants MH47588 and MH62169.

References

- Gunderson JG, Links PS. Borderline Personality Disorder: A Clinical Guide. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Links PS, Heslegrave R, van Reekum R. Prospective follow-up study of borderline personality disorder: Prognosis, prediction of outcome, and axis II comorbidity. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;43:265–70. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen EJ. The psychology of disability. Psychiatric Annals. 1977;7:90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Modestin J, Villiger C. Follow-up study on borderline versus nonborderline personality disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1989;30:236–244. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(89)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell R, Alfredsson E, Berg M, Crafoord K, Lagerlof A, Arkel I, et al. Clinical significance of outcome in long-term follow-up of borderline patients at a day hospital. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1993;87:405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Butler M, Dakroub H, Pole M. Borderline personality symptomatology and employment disability: A survey among outpatients in an internal medicine clinic. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;8:153–157. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Hruschka J, Vasudevan A, Miller SN. Disability and borderline personality symptoms. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:442. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.5.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, et al. Functional impairment in schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:276–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration. Annual Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2007. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) I: History, rational, and description. Archives General Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG. The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: Inter-rater and test-retest reliability. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1987;28:467–480. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Psychosocial functioning of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:19–29. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.1.19.62178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. Mental health service utilization of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:28–36. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: Discriminating BPD from other axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]