Abstract

Background

As prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programs and HIV treatment programs rapidly expand in parallel, it is important to determine factors that influence the transition of HIV-infected women from maternal to continuing care.

Design

This study aimed to determine rates and co-factors of accessing HIV care by HIV-infected women exiting maternal care. A cross-sectional survey of women who had participated in a PMTCT research study and were referred to care programs in Nairobi, Kenya was conducted.

Methods

A median of 17 months following referral, women were located by peer counselors and interviewed to determine whether they accessed HIV care and what influenced their care decisions. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the association between client characteristics and access to care.

Results

Peer counselors traced 195 (82%) residences, where they located 116 (59%) participants who provided information on care. Since exit, 50% of participants had changed residence, and 74% reported going to the referral HIV program. Reasons for not accessing care included lack of money, confidentiality, and dislike of the facility. Women who did not access care were less likely to have informed their partner of the referral (p=0.001), and were less likely believe that highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is effective (p<0.01). Among those who accessed care, 33% subsequently discontinued care, most because they did not qualify for HAART. Factors cited as barriers to access included stigma, denial, poor services, and lack of money. Factors that were cited as making care attractive included health education, counseling, free services, and compassion.

Conclusion

A substantial number of women exiting maternal care do not transit to HIV care programs. Partner involvement, a standardized referral process and more comprehensive HIV education for mothers diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy may facilitate successful transitions between PMTCT and HIV care programs.

Keywords: PMTCT, access, HIV

Background

During the last five years, large donor support from programs such as the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and malaria (GFATM) has enabled massive scaled up of HIV care programs in many African countries. With a goal toward universal access of HIV treatment and prevention to all who need them, efforts under the 3×5 campaign sought to treat three million people with antiretroviral therapy (ARTs) by 2005. By 2007, increased coverage of antiretroviral treatment in poorer countries resulted in three million people in developing countries with access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and an estimated 200,000 children receiving treatment (United Nations, 2009). In Kenya, 177,000 adults and children were accessing ART by 2007 (World Health Organization, 2008). While these increases are remarkable, this constitutes only 38% of the estimated number of individuals requiring ART in Kenya.

Concurrently, an increasing number of women are diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy as part of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs. In Kenya, the proportion of pregnant women accessing PMTCT services increased from 24% in 2004 to 69% in 2007 (World Health Organization, 2008). Despite improvements in access to PMTCT, globally, only 12% of pregnant women living with HIV identified during antenatal care were assessed for their eligibility to receive ARTs for their own health. In Kenya, it has been observed that only half of pregnant women referred for long-term HIV care and treatment link with care programs after PMTCT (NASCOP, 2005).

Little is known regarding the factors that influence maternal decision-making regarding accessing HIV care in resource-limited settings, particularly among women who do not report at all to HIV care facilities. For HIV-infected mothers, personal preferences, socioeconomic and partner characteristics, and HIV literacy may influence the decision to report to an HIV care facility. Increasing the efficiency of referral between PMTCT and HIV care is an important opportunity to improve maternal health. In this study, we evaluated rates of accessing care, as well as co-factors for failure to access care among mothers referred to HIV care programs in Nairobi, Kenya.

Methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington and Kenya Medical Research Institute. This cross-sectional, targeted evaluation surveyed post-exit women who had participated in a PMTCT study with two years of maternal postpartum follow-up, and who were given referral letters to access HIV care at the nearest health facility at study exit. The parent study was conducted from October 1999 to June 2005, following 296 HIV positive pregnant women from four Nairobi City Council clinics (Otieno et al., 2007). During enrollment, details of residential address were taken and a peer counselor sent to identify each home. All women had been given referral letters at study exit, regardless of their HIV staging, in order to secure enrollment in the HIV programs that were being rolled out at the time. Of the 296 women from the initial study, 42 were lost to follow-up and 16 died during the study, resulting in 238 mothers given referrals at exit.

In this current study, we used the address description in the records of each woman and used the same peer counselors from the original study to retrace the homes. Challenges included the death of one of the peer counselors, a number of the participants were living in informal dwellings, and mobility or change of residence was very common. Between July and November 2005, at a median of 17 months (interquartile ranges (IQR), 11–22) post-exit from the parent study, peer counselors visited homes of women to determine whether they had accessed and continued in HIV care. Attempts to trace women who had changed their residence were made through either telephone calls or inquiries from the neighbors to get direction to new residence.

Once located, women were invited to participate in a survey following written informed consent. Information on the woman’s current residence; socioeconomic and marital status; obstetric and contraceptive history; and partner involvement was collected. Knowledge and beliefs related to HIV/AIDS and antiretroviral drugs were also assessed. Women were asked to free-list factors that they perceived to hinder or positively influence accessing HIV care. For women who had not gone to the HIV care facility, additional questions on reasons were posed. Women who had either not accessed HIV care or had accessed care but dropped out were again encouraged and re-referred to nearby active HIV care programs. Women were interviewed only once during the study.

Each qualitative quote was analyzed by the Principal Investigator and assigned to related clusters for coding by concept or idea. Validation of initial coding was conducted in consultation with a social scientist before establishing the final framework. STATA SE 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used in quantitative data analysis. Categorical variables were described using frequencies, and continuous variables were described using medians and IQR. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the association between client characteristics and access to HIV care programs.

Results

Sample description

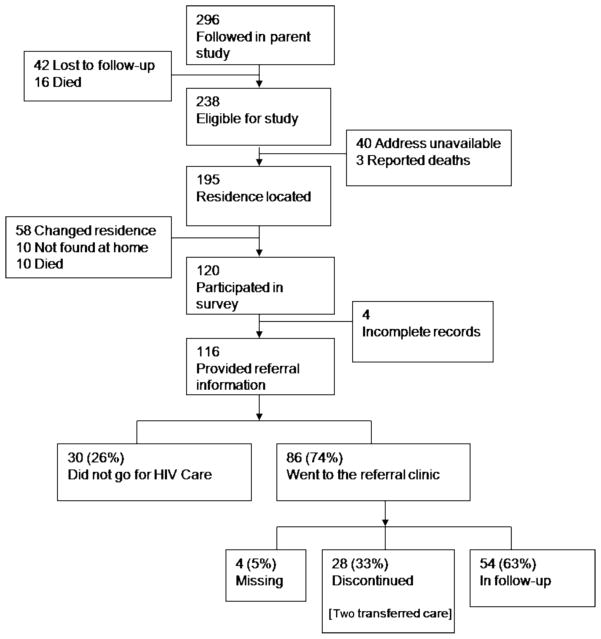

Figure 1 summarizes referral, home-tracing, and access to care. Of 238 women eligible for survey, 40 were not traced due to missing record of home addresses and three deaths were reported. Of 195 attempted home visits, 120 women were located, and 116 provided information related to access to HIV care. Those who were interviewed had, on average, 0.6 more years of education (p=0.04) and were also 1.5 years older (p=0.007) than those who were not interviewed.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of women and transition to referral HIV care programs.

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of 116 women who were interviewed. The median age was 30 (IQR, 23–38) years and 64 (55%) of the women had education above primary level. Half of the women reported that they changed residence since they had exited the PMTCT study. Among women who were married or in a steady relationship, few had changed partners since study participation, 79% had informed their partner of the referral for HIV care and 64% knew their partner had been tested for HIV. Among the women who knew their partner had been tested, 56% reported that their partners were HIV positive while 6% did not know the result. Of the partners who were HIV positive, 41% were reported to be already on HAART.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-1 infected women who participated in the survey.

| Number (%) or median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics (n=116) | |

| Age (years) | 30 (23–38) |

| Marital status | |

| Married (monogamous) | 68 (58.6) |

| Married (polygamous) | 15 (12.9) |

| Steady boyfriend | 2 (1.7) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 25 (201.5) |

| Single | 6 (5.2) |

| Education status | |

| Primary education | 52 (44.4) |

| Secondary education | 56 (47.9) |

| College | 9 (7.7) |

| Residential conditions (n=116) | |

| Changed residence | 57/113 (50.4) |

| Number of rooms | 1 (1–2) |

| Household density (people/rooms) | 3 (2–4) |

| House rent, KSh. (n=112) | 1650 (1200–3000) |

| Current employment | 67/115 (58.3) |

| Household income | |

| Unemployed | 8 (6.9) |

| Either self or partner employed | 75 (64.7) |

| Both self and partner employed | 33 (28.5) |

| Sexual and obstetric history (n=116) | |

| Number of lifetime partners (n=115) | 3 (2–4) |

| Ever commercial sex (n=115) | 2 (1.7) |

| Ever used contraceptive | 101 (87.1) |

| Number of pregnancies | 3 (2–3) |

| Partner informationa | |

| Years in relationship (n=83) | 6 (5–10) |

| Changed partner since study participation | 6/84 (7.1) |

| Informed partner of referral for HIV care | 65/82 (79.3) |

| Partner has been tested for HIV | 53/83 (63.9) |

| Partner HIV statusb | |

| Positive | 29/52 (55.8) |

| Negative | 20/52 (38.5) |

| Don’t know | 3/52 (5.8) |

| Partner is on ARV drugsc | 12 (41.4) |

Among married or in a steady relationship (n=85).

Among married or in a steady relationship and knows partner was tested (n=53).

Among married or in a steady relationship and tested and partner knows HIV+ (n=29).

Accessing HIV care and continuing in HIV care programs

Of the 116 women reporting on access to health care, 74% reported that they had sought services at an HIV care program following their referral (Figure 1). Among these, 54 (63%) continued in follow-up, of whom 33 (61%) were started on HAART. Twenty-eight (33%) women who went to the clinic were referred to stopped going to the facility for HIV care, although two women elected to change clinics. Thus, of the 116 women who participated in the study, less than half (47%) reported continuing their HIV care in the same facility. The main reason for discontinuing HIV care was not being eligible for HAART. Other reasons included migration or long distance to facility, side effects of medication, dislike of the facility, pregnancy, child illness, and confidentiality issues.

Women who did not go to an HIV care program at all most frequently cited lack of money and dislike of the facility as reasons for not going. Other issues included lack of interest, systematic gaps in the referral process, confidentiality, partner issues, distance/migration, not being ready, fear, and family illness.

HIV literacy

Women’s knowledge and beliefs on HIV/AIDS disease and care methods is summarized in Table 2. All women had some knowledge of availability of methods to treat HIV/AIDS. A total of 75% of women knew that combined HAART is a method of managing HIV/AIDS. Over half of women (56%) knew that treatment was lifelong, and most women (89%) believed combined HAART was effective.

Table 2.

Knowledge and beliefs on HIV/AIDS management.

| Knowledge | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Reported method to treat HIV/AIDS (n=116) | |

| Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis | 34 (29.3) |

| TB treatment | 16 (13.8) |

| Single ARVs | 33 (28.5) |

| HAART | 88 (75.9) |

| Herbal treatment | 12 (10.3) |

| Traditional healers | 1 (0.9) |

| Duration of treatment with ARVs (n=114) | |

| For life | 64 (56.1) |

| Varied durations | 5 (4.4) |

| Do not know | 45 (39.5) |

| Believe that combined ARV drugs are effective (n=113) | 101 (89.4) |

| Report that treatment should be started when (n=115) | |

| As soon as diagnosis is made | 14 (12.2) |

| Any time during the infection | 14 (12.2) |

| When immunity or protective cells are low | 64 (55.7) |

| Beliefs of how ARVs work (n=114) | |

| Eradicate the virus from the body | 8 (7.0) |

| Reduce the levels of virus in the body | 94 (82.5) |

| May increase the levels of virus in the body | 82 (71.9) |

| Do nothing | 6 (5.3) |

| May increase the resistance of the virus | 10 (8.8) |

Perceptions regarding HIV care programs

Factors quoted as major barriers to accessing HIV care program are summarized in Table 3. Most commonly listed factors included stigma, spouse negligence or violence, ignorance or poor education, denial, lack of faith in the health care services, and lack of money. Factors listed that would encourage access to HIV care program included: health education such as holding seminars, education through the press or advertisements; provision of counseling and group therapy; provision of free drugs and care; compassionate care such as “showing love and acceptance by medical staff and others that matter to those who are infected by HIV”; and provision of free food or other incentives.

Table 3.

Factors free-listed by participants as influencing access to HIV care programs (Related responses coded to listed groups) (n=116).

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Factors listed as major barriers to accessing HIV care | |

| Stigma | 90 (77.6) |

| Spouse-related issues (violence, negative attitude, or lack of disclosure) | 33 (28.5) |

| Ignorance and or poor education | 26 (22.4) |

| Denial | 25 (21.6) |

| Lack of faith in the health care services and or care providers | 22 (19.0) |

| Lack of money | 22 (19.0) |

| Fear of side effects of drugs | 12 (10.3) |

| Inaccessible health facilities | 6 (5.2) |

| Lack of time | 3 (2.6) |

| Being too sick | 3 (2.6) |

| Do not know | 3 (2.6) |

| Other reasons | 4 (3.5) |

| Factors quoted as major facilitators of access to HIV care programs | |

| Health education | 60 (51.7) |

| Provision of counseling or group therapy | 48 (41.4) |

| Provision of free drugs and care | 28 (24.1) |

| Love and care | 14 (12.1) |

| Provision of free food and other incentives | 14 (12.1) |

| Stigma reduction including public disclosure | 8 (6.9) |

| Assurance of privacy and confidentiality | 6 (5.2) |

| Involving partners in care | 2 (1.7) |

| Community meetings | 2 (1.7) |

| Do not know | 5 (4.3) |

| Others | 4 (3.5) |

Factors associated with failing to access HIV care

Factors significantly associated with failing to access HIV care programs were determined in univariate analyses (Table 4). Compared to women who accessed HIV care, those who did not access HIV care were less likely to have informed their partners of referral to HIV care 50% vs. 87% (p=0.001) and less likely to report correct information and beliefs on HIV/AIDS disease and treatment, such as: knowledge that HAART could benefit HIV care (75% vs. 94%, p<0.01), knowledge of drugs to treat HIV (80% vs. 94%, p=0.03), and that HAART was not started at diagnosis (27% vs. 7%, p<0.01). More women who accessed care knew that treatment is for life and knew that HAART reduces levels of HIV virus in the body when compared to women who did not access HIV care (p=0.05 each).

Table 4.

Factors associated with access to HIV care program.

| Variable | Accessed care, N (%) | Did not access care, N (%) | p-Value Fishers exact |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=86a | n=30a | ||

| Sociodemographic factors | |||

| Age (<median 30 years) | 48 (55.8) | 18 (60.0) | 0.83 |

| Marital status (married) | 61 (70.9) | 22 (73.3) | 1.00 |

| Education status (above primary) | 50 (58.1) | 14 (46.7) | 0.30 |

| Change of residence | 43/83 (51.8) | 14 (46.7) | 0.67 |

| House rent (<median 1650KSh) | 43/83 (51.8) | 10/29 (34.5) | 0.13 |

| Rooms (>median 1) | 32 (37.2) | 17 (56.7) | 0.09 |

| House density (>3 people/room) | 38 (44.2) | 14 (46.7) | 0.83 |

| Knowledge and attitudes | |||

| Know of drugs used in HIV | 81 (94.2) | 24 (80.0) | 0.03 |

| Believe that combined drugs are effective | 80/85 (94.1) | 21/28 (75.0) | 0.009 |

| Believe treatment for HIV should be started only when the body’s immunity is low | 51/85 (60.0) | 13 (43.3) | 0.14 |

| Believe that the treatment for HIV should be started at diagnosis | 6/85 (7.1) | 8 (26.7) | 0.009 |

| Believe that treatment for HIV should be for life | 52/84 (61.9) | 12 (40.0) | 0.05 |

| Believe that HAART reduces levels of HIV | 74/84 (86.9) | 21 (70.0) | 0.05 |

| Partner information | |||

| Partner informed of resultsb | 57/61 (93.4) | 18/23 (78.3) | 0.11 |

| Partner tested for HIVb | 41/60 (68.3) | 12/23 (52.2) | 0.21 |

| Partner HIV positivec | 23/38 (60.5) | 6/11 (54.6) | 0.74 |

| Partner on treatment for HIVd | 10/23 (43.5) | 2/6 (33.3) | 1.00 |

| Partner informed of referral | 55/62 (88.7) | 10/20 (50.0) | 0.001 |

Unless otherwise indicated.

Among married or in a steady relationship (n=85).

Among married or in a steady relationship and knows partner was tested (n=53).

Among married or in a steady relationship, tested and partner knows HIV positive (n=29).

Discussion

While data from HAART programs provide insight on individuals who access care and who continue in follow-up, little is known about individuals who decline to access HIV care. Many women are diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy as part of PMTCT programs, and timely referral to a HIV care program with early initiation of HAART can delay progression to AIDS and improve survival (Egger et al., 2002; Hogg et al., 2001; Kitahata et al., 2009).

During pregnancy and postpartum, the approach to HIV-infected women prioritizes prevention of infant HIV infection. However, the fourth component in the UN Strategy to prevent HIV infections in infants is providing care for HIV-infected mothers as well as their infants (World Health Organization, 2003). There may also be infant survival gains when HIV-infected mothers are managed with cotrimoxazole prophylaxis or HAART. In Uganda, there was an 81% observed reduction in mortality among uninfected children if their HIV-infected parents were receiving HAART and cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (Mermin et al., 2008), and a threefold increase in mortality among HIV-negative children associated with death of a HIV-infected parent (Mermin et al., 2005).

The access rate demonstrated in this study (74%), though higher than the 2005 Kenya national report, underscores the substantial proportion of women who elected not to transition to HIV care following maternal care. Similar trends have been reported in other African countries where, regardless of high levels of counseling, there is still unacceptable loss in access of important interventions (Manzi et al., 2005; World Health Organization, 2008). Furthermore, although 74% of those in our study presented at their referral site, a third of those women ceased attending clinic, leaving less than half of all referred women in an HIV care program. This is especially concerning since one would expect high levels of follow-up from presumably motivated women who had participated in a research study for one to two years.

An important factor in the transition from PMTCT to long-term HIV care referral is that women diagnosed with HIV in pregnancy are generally healthy and asymptomatic, while women otherwise entering HIV treatment do so as a result of symptoms. The majority of women transitioning from PMTCT to HIV care will not be HAART eligible and may not see other benefits of follow-up and prophylaxis to be as compelling as receiving HAART. In fact, the most commonly cited reason for dropping out of care after presenting to referral facility was ineligibility for HAART. Asymptomatic or HAART-ineligible HIV-infected individuals are at a unique window of opportunity to optimize their health and survival. However, they may not yet realize the benefits of this approach.

Personal factors such as HIV partner influence, knowledge, and stigma were frequently mentioned in this group of women. Nearly, 30% of women reported partner-related factors such as violence, negative attitude to HIV care, or lack of disclosure as major barriers to access of HIV care. This is consistent with previous findings in the region; men may exert considerable influence on how their female partners access health care and, in some cases, may become violent upon learning of their partner’s HIV status (Ezechi et al., 2009). Previous studies in Kenya have also noted that male partners influenced feeding choices of infants and compliance with PMTCT antiretrovirals (Kiarie, Kreiss, Richardson, & John-Stewart, 2003; Kiarie, Richardson, Mbori-Ngacha, Nduati, & John-Stewart, 2004).

Women who accessed HIV care were significantly more knowledgeable regarding HAART and HIV care than those who did not. It is not surprising that accurate knowledge regarding HIV treatment would influence individuals to make appropriate decisions on their own care. Alternately, women in HIV care who are exposed to educational messages during their clinic visits may be more knowledgeable than women who do not present for care. It is impossible to determine whether knowledge leads to improved uptake or if uptake leads to better knowledge.

In the free listing by women, stigma was overwhelmingly mentioned as a barrier to access (78%). Similarly, other reports note that stigma is one of the major barriers to provision of care to people living with HIV in Africa (Greeff & Phetlhu, 2007). Accessing maternal care at Maternal Child Health clinics does not openly identify women as HIV infected in the same way that accessing HIV care at well-known HIV care programs would. Thus, the drop off in participation between maternal programs to HIV care likely involves a combination of specific interest in prevention of infant infection, perceptions that asymptomatic HIV does not require care, and concern regarding stigma that may result from accessing programs solely defined as HIV care programs. Healthy women without symptoms or evidence of HIV may perceive much greater social cost from HIV care programs than maternal care programs.

Most of the clients interviewed were poor and cited difficulties with lack of money and transport to the health facilities. This is mirrored by the desire of the clients interviewed for availability of food, drugs, and even money to facilitate successful access to health care, while lack of the same were listed as barriers to accessing health care. Low socioeconomic status, poverty, and unemployment have been cited as major reasons for delay in accessing care by HIV-infected patients in previous studies (Joy et al., 2008; Kiwanuka et al., 2008; Louis, Ivers, Smith Fawzi, Freedberg, & Castro, 2007).

Finally, other factors related to quality of HIV care and establishment of trust with service providers were listed as promoters of access to care and included: love, care, and assurance of confidentiality. Among women not accessing HIV care after referral, dislike of the facility was frequently listed, and lack of funds was listed as the main reason for not appearing to care. As we report here, a third of the clients who reported for HIV care subsequently either dropped out of care or changed clinics, highlighting the need for quality and compassionate care.

The main strength of this study is the fact that we addressed HIV programs from the perspective of referred clients who either did or did not access or continue care. We involved women exiting maternal programs, which reflect an important population that has relatively recent diagnosis of HIV and may perceive maternal child health follow-up differently from HIV care.

Limitations of the study include the cross-sectional nature of the evaluation at one time. Despite tracing efforts, it was not possible to contact a large percentage of women from the parent study, which may have contributed to selection bias. Nearly half of the original study population was not located. Other limitations include use of reported information from the clients. It was not possible to assess the practices at the health facilities, available community services, peer groups, or partner education that may influence access to HIV care. This study was also conducted on women who had been exposed to routine care and health education in a prospective PMTCT research study who may not be representative of PMTCT clients who have less time in follow-up (up to nine months), and less intensive involvement with providers. Finally, given the rapid increased ART access during and since this study, community perceptions are a moving target, which are difficult to capture with time-limited surveys. However, despite these limits it is likely that common themes will be retained and can be incorporated into improving programs.

It is important to make an efficient transition between maternal care to general HIV care in order to maximize health benefits to both women and children. Highlighting potential benefits of accessing HIV care pre-HAART may be one way to increase uptake among women transitioning between PMTCT and HIV care. It is plausible too, that providing standardized education on HIV care (including HAART, as well as pre-HAART interventions), the importance of HIV care, and the process of referral and accessing HIV care at the time women exit maternal PMTCT programs would increase successful referral. This requires standardization of an evidence-based referral process across the health system and early intervention in the PMTCT process. Peer counselors from the HIV care programs to which women are referred may also provide a link between PMTCT and HIV care programs, and they may be able to work with mothers at the time of referral to negotiate potential barriers that may block successful referral. These interventions should be evaluated in future research and care programs.

In conclusion, we noted that a substantial number of women elected not to access HIV care following referral after exiting maternal care, citing a variety of reasons. Partner involvement and knowledge about HIV treatment were strong determinants of accessing HIV care and receiving HAART was an important predictor of continuing in HIV care. Addressing these determinants and potential barriers may be useful in increasing effective referral between PMTCT and HIV care and treatment programs.

References

- Egger M, May M, Chene G, Phillips AN, Ledergerber B, Dabis F, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: A collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezechi OC, Gab-Okafor C, Onwujekwe DI, Adu RA, Amadi E, Herbertson E. Intimate partner violence and correlates in pregnant HIV positive Nigerians. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;280(5):745–752. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeff M, Phetlhu R. The meaning and effect of HIV/AIDS stigma for people living with AIDS and nurses involved in their care in the North West Province, South Africa. Curationis. 2007;30(2):12–23. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v30i2.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RS, Yip B, Chan KJ, Wood E, Craib KJ, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. Rates of disease progression by baseline CD4 cell count and viral load after initiating triple-drug therapy. JAMA. 2001;286(20):2568–2577. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK, Lima VD, Rustad CA, Zhang W, et al. Impact of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status on HIV disease progression in a universal health care setting. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(4):500–505. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181648dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiarie JN, Kreiss JK, Richardson BA, John-Stewart GC. Compliance with antiretroviral regimens to prevent perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Kenya. AIDS. 2003;17(1):65–71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000042938.55529.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, Mbori-Ngacha D, Nduati RW, John-Stewart GC. Infant feeding practices of women in a perinatal HIV-1 prevention study in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35(1):75–81. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, Merriman B, Saag MS, Justice AC, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(18):1815–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwanuka SN, Ekirapa EK, Peterson S, Okui O, Rahman MH, Peters D, et al. Access to and utilisation of health services for the poor in Uganda: A systematic review of available evidence. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008;102(11):1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis C, Ivers LC, Smith Fawzi MC, Freedberg KA, Castro A. Late presentation for HIV care in central Haiti: Factors limiting access to care. AIDS Care. 2007;19(4):487–491. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzi M, Zachariah R, Teck R, Buhendwa L, Kazima J, Bakali E, et al. High acceptability of voluntary counselling and HIV-testing but unacceptable loss to follow up in a prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in rural Malawi: Scaling-up requires a different way of acting. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2005;10(12):1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermin J, Lule J, Ekwaru JP, Downing R, Hughes P, Bunnell R, et al. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis by HIV-infected persons in Uganda reduces morbidity and mortality among HIV-uninfected family members. AIDS. 2005;19(10):1035–1042. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000174449.32756.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermin J, Were W, Ekwaru JP, Moore D, Downing R, Behumbiize P, et al. Mortality in HIV-infected Ugandan adults receiving antiretroviral treatment and survival of their HIV-uninfected children: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):752–759. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASCOP. AIDS in Kenya, trends, interventions and impact. Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya Ministry of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Otieno PA, Brown ER, Mbori-Ngacha DA, Nduati RW, Farquhar C, Obimbo EM, et al. HIV-1 disease progression in breast-feeding and formula-feeding mothers: A prospective 2-year comparison of T cell subsets, HIV-1 RNA levels, and mortality. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;195(2):220–229. doi: 10.1086/510245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The millenium development goals report 2009. New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Strategic approaches to the prevention of HIV infection in infants. Geneva: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Towards universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]