Abstract

Days out of role because of health problems are a major source of lost human capital. We examined the relative importance of commonly occurring physical and mental disorders in accounting for days out of role in 24 countries that participated in the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Face-to-face interviews were carried out with 62 971 respondents (72.0% pooled response rate). Presence of ten chronic physical disorders and nine mental disorders was assessed for each respondent along with information about the number of days in the past month each respondent reported being totally unable to work or carry out their other normal daily activities because of problems with either physical or mental health. Multiple regression analysis was used to estimate associations of specific conditions and comorbidities with days out of role, controlling by basic socio-demographics (age, gender, employment status and country). Overall, 12.8% of respondents had some day totally out of role, with a median of 51.1 a year. The strongest individual-level effects (days out of role per year) were associated with neurological disorders (17.4), bipolar disorder (17.3) and post-traumatic stress disorder (15.2). The strongest population-level effect was associated with pain conditions, which accounted for 21.5% of all days out of role (population attributable risk proportion). The 19 conditions accounted for 62.2% of all days out of role. Common health conditions, including mental disorders, make up a large proportion of the number of days out of role across a wide range of countries and should be addressed to substantially increase overall productivity.

Keywords: mental disorders, chronic disease, disability, productivity loss, prevalence, burden of disease

Introduction

A growing body of research aims to quantify the societal impacts of physical and mental disorders on functioning in order to influence social policy decisions about investing in health care.1, 2, 3, 4 One important component of this research examines effects of health problems on days out of role. For example, these studies have estimated that there are 3.6 billion annual health-related days out of role in the United States,5 and that the annual costs of work loss days due to brain disorders in Europe exceed 178 billion Euros.6 It is also important to quantify the relative importance of specific disorders in accounting for these effects, and to evaluate the extent to which expanded outreach and best-practices treatment of the disorders associated with the largest losses reduce these effects. The first step in such a program of research should be to distinguish relative effects of specific disorders. This requires epidemiological data on a broad range of disorders so as to adjust for the high rates of comorbidity within and between physical and mental disorders.7, 8 Although some studies of this sort have been carried out in the United States,5, 8 we are not aware of any comparable studies in most other parts of the world.

The current report presents data of this sort from the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) surveys (www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/WMH). The WMH initiative was launched by the WHO to carry out general population surveys in countries throughout the world to assess the prevalence and correlates of mental disorders.9 One section in the WMH interviews assesses the presence of commonly occurring chronic physical disorders in order to facilitate analysis of the comparative effects of mental and physical disorders on role functioning. WMH data from 24 countries are used in this report to examine these relative effects on days out of role in the month before interview. A novel method is used to estimate these effects in such a way as to adjust for comorbidity.

Materials and methods

Samples

A total of 25 WMH surveys were carried out in 24 countries (Table 1). Of these countries, 6 were classified in 2007 by the World Bank10 as low- or lower-middle-income countries (Colombia, India, Iraq, Nigeria, Peoples' Republic of China (PRC) and Ukraine), 6 as upper-middle-income countries (Brazil, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Mexico Romania, and South Africa) and 12 as higher-income countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the United States). All surveys were based on probability samples of the adult household population of the participating countries. The samples were selected either to be nationally representative (in a majority of countries), representative of all urbanized areas in the country (Colombia and Mexico) or representative of particular regions of the country (Brazil, India, Japan, Nigeria and PRC). More details about sampling are provided elsewhere.11 The weighted (by sample size) average response rate across surveys was 72.0% ranging from 45.9% (France) to 95.2% (Iraq) (Table 1).

Table 1. WMH sample characteristics by World Bank income categoriesa.

| Survey | Sample characteristicsc | Field dates | Age range |

Sample size |

Response rated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part I | Part IIe | ||||||

| I. Low/lower-middle-income countries | |||||||

| Colombia | NSMH | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in all urban areas of the country (approximately 73% of the total national population) | 2003 | 18–65 | 4426 | 2381 | 87.7 |

| India | WMHI | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in Pondicherry region. NR | 2003–2005 | 18+ | 2992 | 1373 | 98.8 |

| Iraq | IMHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2006–2007 | 18+ | 4332 | 4332f | 95.2 |

| Nigeria | NSMHW | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of households in 21 of the 36 states in the country, representing 57% of the national population. The surveys were conducted in Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa and Efik languages. | 2002–2003 | 18+ | 6752 | 2143 | 79.3 |

| PRC | B-WMH S-WMH | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in the Beijing and Shanghai metropolitan areas. | 2002–2003 | 18+ | 5201 | 1628 | 74.7 |

| PRC | Shenzhen | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents and temporary residents in the Shenzhen area. | 2006–2007 | 18+ | 7134 | 2475 | 80.0 |

| Ukraine | CMDPSD | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002 | 18+ | 4725 | 1719 | 78.3 |

| Total | 35 562 | 16 051 | 82.6 | ||||

| II. Upper-middle-income countries | |||||||

| Brazil | São Paulo Megacity | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in the São Paulo metropolitan area. | 2005–2007 | 18+ | 5037 | 2942 | 81.3 |

| Bulgaria | NSHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2003–2007 | 18+ | 5318 | 2233 | 72.0 |

| Lebanon | LEBANON | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002–2003 | 18+ | 2857 | 602 | 70.0 |

| Mexico | M-NCS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in all urban areas of the country (approximately 75% of the total national population). | 2001–2002 | 18–65 | 5782 | 2362 | 76.6 |

| Romania | RMHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2005–2006 | 18+ | 2357 | 2357f | 70.9 |

| South Africa | SASH | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2003–2004 | 18+ | 4315 | 4315f | 87.1 |

| Total | 25 666 | 14 811 | 76.6 | ||||

| III. High-income countries | |||||||

| Belgium | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals residing in households from the national register of Belgium residents. NR | 2001–2002 | 18+ | 2419 | 1043 | 50.6 |

| France | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered sample of working telephone numbers merged with a reverse directory (for listed numbers). Initial recruitment was by telephone, with supplemental in-person recruitment in households with listed numbers. NR | 2001–2002 | 18+ | 2894 | 1436 | 45.9 |

| Germany | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals from community resident registries. NR | 2002–2003 | 18+ | 3555 | 1323 | 57.8 |

| Israel | NHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of individuals from a national resident register. NR | 2002–2004 | 21+ | 4859 | 4859f | 72.6 |

| Italy | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals from municipality resident registries. NR | 2001–2002 | 18+ | 4712 | 1779 | 71.3 |

| Japan | WMHJ2002–2006 | Un-clustered two-stage probability sample of individuals residing in households in eleven metropolitan areas | 2002–2006 | 20+ | 4129 | 1682 | 55.1 |

| The Netherlands | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals residing in households that are listed in municipal postal registries. NR | 2002–2003 | 18+ | 2372 | 1094 | 56.4 |

| New Zealandb | NZMHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2003–2004 | 18+ | 12 790 | 7312 | 73.3 |

| N. Ireland | NISHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2004–2007 | 18+ | 4340 | 1708 | 68.4 |

| Portugal | NMHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2008–2009 | 18+ | 3849 | 2060 | 57.3 |

| Spain | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2001–2002 | 18+ | 5473 | 2121 | 78.6 |

| United States | NCS-R | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002–2003 | 18+ | 9282 | 5692 | 70.9 |

| Total | 60 674 | 32 109 | 65.4 | ||||

| IV. Total | 121 902 | 62 971 | 72.0 | ||||

Abbreviations: B-WMH, The Beijing World Mental Health Survey; CMDPSD, Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption; ESEMeD, The European Study Of The Epidemiology Of Mental Disorders; IMHS, Iraq Mental Health Survey; LEBANON, Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation; M-NCS, The Mexico National Comorbidity Survey; NCS-R, The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication; NHS, Israel National Health Survey; NISHS, Northern Ireland Study of Health and Stress; NMHS, Portugal National Mental Health Survey; NR, Nationally Representative; NSHS, Bulgaria National Survey of Health and Stress; NSMH, The Colombian National Study of Mental Health; NSMHW, The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; NZMHS, New Zealand Mental Health Survey; RMHS, Romania Mental Health Survey; SASH, South Africa Health Survey; S-WMH, The Shanghai World Mental Health Survey; WMH, World Mental Health; WMHI, World Mental Health India; WMHJ2002–2006, World Mental Health Japan Survey.

The World Bank. (2008). Data and Statistics. Accessed 12 May 2009 at: http://go.worldbank.org/D7SN0B8YU0

New Zealand interviewed respondents aged 16+ but for the purposes of cross-national comparisons, we limit the sample to those aged 18+.

Most WMH surveys are based on stratified multistage clustered area probability household samples in which samples of areas equivalent to counties or municipalities in the United States were selected in the first stage followed by one or more subsequent stages of geographic sampling (for example, towns within counties, blocks within towns, households within blocks) to arrive at a sample of households, in each of which a listing of household members was created and one or two people were selected from this listing to be interviewed. No substitution was allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed. These household samples were selected from Census area data in all countries other than France (where telephone directories were used to select households) and The Netherlands (where postal registries were used to select households). Several WMH surveys (Belgium, Germany, Italy) used municipal resident registries to select respondents without listing households. The Japanese sample is the only totally unclustered sample, with households randomly selected in each of the four sample areas and one random respondent selected in each sample household. Of the 24 surveys, 18 are based on nationally representative (NR) household samples.

The response rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of households in which an interview was completed to the number of households originally sampled, excluding from the denominator households known not to be eligible either because of being vacant at the time of initial contact or because the residents were unable to speak the designated languages of the survey. Mean response rate across all surveys is 72.0%.

Only respondents from Part II who were asked questions about chronic conditions are included.

Iraq, Israel, Romania and South Africa did not have Part II sample.

All WMH interviews were administered face to face by trained lay interviewers using training, and field quality control procedures described elsewhere.9, 12, 13 Informed consent was obtained before beginning interviews, using procedures approved by the institutional review board of the organization coordinating the survey in each country. Each interview had two parts. Part I, which was administered to all respondents, contained assessments of core mental disorders. All Part I respondents who reported a number of symptoms of any core mental disorder plus a probability subsample of other Part I respondents were administered Part II, which assessed correlates and disorders of secondary interest to the study. The assessment of physical disorders was included in Part II. Part II is consequently the focus of the current report. The Part II data were weighted to adjust for the undersampling of Part II non-cases and to adjust for residual discrepancies between sample and population distributions on a range of socio-demographic and geographic variables. The total number of Part II respondents across surveys was 62 971, with individual country sample sizes ranging from 602 (Lebanon) to 7312 (New Zealand).

Measurement

Mental disorders

Mental disorders were assessed with version 3.0 of the WHO CIDI (Composite International Diagnostic Interview), a fully structured lay-administered interview designed to generate research diagnoses of common mental disorders according to the definitions and criteria of both the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition) and ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision) diagnostic systems.14 The nine mental disorders considered here include mood disorders (major depressive disorder and bipolar I-II disorder), anxiety disorders (panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)) and substance disorders (alcohol abuse with and without dependence and drug abuse with and without dependence). Only disorders present in the 12 months before interview were considered. A clinical reappraisal study with blinded clinical follow-up interviews using the SCID (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV)15 in several WMH surveys (France, Italy, Spain and United States) found generally good concordance between diagnoses based on the CIDI and those based on the SCID.16

Chronic physical disorders

Physical disorders were assessed with a standard chronic disorder checklist. Checklists of this sort have been shown to yield more complete and accurate reports of disorder prevalence than estimates derived from responses to open-ended questions.17, 18 Reports based on such checklists have been shown in previous methodological studies to have moderate to good concordance with medical records.19, 20

The ten conditions considered here were: arthritis, cancer, cardiovascular disorders (heart attack, heart disease, hypertension and stroke), chronic pain conditions (chronic back or neck pain and other chronic pain), diabetes, migraine or other frequent or severe headaches, insomnia, neurological disorders (multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's and epilepsy or seizures), digestive disorders (stomach or intestinal ulcers and irritable bowel disorder) and respiratory disorders (seasonal allergies, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema). The symptom-based disorders in this set (arthritis, pain disorders, heart attack and stroke) were assessed with respondent reports as to whether or not they ever experienced the disorder, whereas the remaining conditions were assessed with respondent reports of whether or not a doctor or other health professional ever told them that they had the disorder. Questions about persistence were also asked about lifetime disorders that can remit. The focus in this report is on disorders present in the 12 months before interview.

Days out of role

A modified version21 of the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS)22, 23 was used to ask respondents the number of days in the 30 days before interview (that is, beginning yesterday and going back 30 days) they were totally unable to work or carry out your normal activities because of problems with either your physical health, your mental health or your use of alcohol or drugs. Good concordance of these reports have been documented, both with payroll records of employed people24, 25 and with prospective daily diary reports.26

Statistical analysis

Multiple regression analysis was used to examine multivariate associations of the physical and mental disorders assessed in the survey with reported days out of role in the past 30 days, controlling for age, gender, employment status and country. As substantial comorbidity was found among the disorders,27 we included terms to capture the effects of comorbidity in the regression models. Given that the number of possible combinations of comorbid disorders in the data (219−20=524 268) far exceeds the number of respondents, it was necessary to impose some structure on the terms used to capture the effects of comorbidity. This was done by including terms for total number of comorbid disorders and separate interaction terms for the extent to which the regression coefficient of each separate disorder changed as a function of number of comorbid disorders, taking into account the size of the coefficients associated with the comorbid disorders. Nonlinear regression methods requiring iterative estimation procedures28 were used for this purpose.

As the outcome variable (a 0–30 measure of number of days out of role) was highly skewed, we investigated a number of different model specifications that included an ordinary least squares regression model and six generalized linear models that considered the conjunction of two link functions (logarithmic or square root) and three error structures (constant, error variance proportional to the mean and error variance proportional to the mean squared). Standard diagnostic procedures to compare model fit29 showed that the ordinary least squares model and generalized linear model with a log link function and constant variance were the two best-fitting models (detailed results of model comparison are available on request).

As the prediction equation includes interaction terms, the predictive effect of each disorder is distributed across a number of different coefficients. Simulation was used to produce a single term to summarize all these component effects. This was done by estimating the predicted value of the outcome for each respondent from the coefficients in the final model (the base estimate) and then repeating this exercise in a modified form at 19 different times, each time assuming that one of the 19 disorders no longer existed. The difference between the predicted mean of the outcome generated by the simulated estimate and the base estimate was divided by the number of respondents with the disorder in question to obtain the estimated individual-level effect of the disorder on the outcomes. The estimated societal-level effect of the disorder was then obtained by multiplying the individual-level estimate by the prevalence of the disorder. The same procedure was used to calculate total effects of any physical disorder, any mental disorder and any disorder.

Because of the fact that the WMH survey data were geographically clustered, weighted means, and design-based methods were needed to obtain accurate estimates of standard errors and statistical significance. The Taylor series linearization method30 implemented in SAS31 was used to do this for the basic model. The more computationally intensive method of jackknife repeated replications,30 implemented in a SAS macro that we wrote for this purpose, was used to obtain standard errors of the simulated estimates of individual- and societal-level disorder effects. Significance tests were consistently evaluated using 0.05-level, two-sided design-based tests.

More information about the methods used in this paper can be obtained from the authors on request.

Results

Major demographic characteristics of the sample are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Sample characteristics by country and country income (The WHO WMH surveys).

| Country | N | Age | Females | Not married | High school or more | Not working |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.e.) | % (s.e.) | % (s.e.) | % (s.e.) | % (s.e.) | ||

| Lower income | ||||||

| Colombia | 2381 | 36.6 (0.4) | 54.5 (1.5) | 43.4 (1.7) | 46.4 (2.1) | 46.4 (1.6) |

| India (Pondicherry) | 1373 | 38.1 (0.6) | 50.0 (1.6) | 30.2 (2.1) | 47.0 (1.9) | 52.1 (1.5) |

| Iraq | 4332 | 36.9 (0.4) | 49.7 (1.0) | 34.4 (1.2) | 35.3 (1.1) | 59.2 (1.2) |

| Nigeria | 2143 | 35.8 (0.4) | 51.0 (1.5) | 39.7 (1.6) | 35.6 (1.3) | 31.1 (1.4) |

| PRC (Beijing, Shanghai) | 1628 | 41.2 (0.6) | 47.7 (1.8) | 33.4 (1.7) | 55.0 (1.6) | 41.2 (2.2) |

| PRC (Shenzhen) | 2475 | 29.1 (0.3) | 50.3 (1.6) | 46.2 (1.3) | 49.4 (1.5) | 8.5 (0.6) |

| Ukraine | 1719 | 46.1 (0.8) | 55.1 (1.3) | 34.9 (1.4) | 81.9 (1.5) | 45.6 (2.1) |

| Middle income | ||||||

| Brazil | 2942 | 39.0 (0.5) | 52.8 (1.4) | 40.2 (1.6) | 47.2 (1.3) | 35.4 (1.1) |

| Bulgaria | 2233 | 47.8 (0.6) | 52.2 (1.3) | 25.7 (1.6) | 64.2 (1.3) | 50.4 (1.9) |

| Lebanon | 602 | 40.3 (0.9) | 48.1 (2.6) | 39.0 (3.2) | 40.5 (2.8) | 48.8 (2.4) |

| Mexico | 2362 | 35.2 (0.3) | 52.3 (1.8) | 32.7 (1.5) | 31.4 (1.6) | 41.6 (1.6) |

| Romania | 2357 | 45.5 (0.4) | 52.4 (1.3) | 30.4 (1.2) | 49.3 (1.7) | 60.7 (1.3) |

| South Africa | 4315 | 37.1 (0.3) | 53.6 (1.0) | 49.7 (1.1) | 37.8 (1.1) | 65.1 (1.4) |

| Higher income | ||||||

| Belgium | 1043 | 46.9 (0.7) | 51.7 (2.4) | 30.2 (1.7) | 69.7 (3.7) | 42.2 (1.4) |

| France | 1436 | 46.3 (0.7) | 52.2 (1.8) | 29.0 (1.8) | — (—) | 37.9 (1.8) |

| Germany | 1323 | 48.2 (0.8) | 51.7 (1.4) | 36.7 (1.7) | 96.4 (0.9) | 43.5 (2.1) |

| Israel | 4859 | 44.4 (0.1) | 51.9 (0.2) | 32.2 (0.6) | 78.3 (0.6) | 39.8 (0.7) |

| Italy | 1779 | 47.7 (0.6) | 52.0 (1.5) | 33.3 (1.6) | 39.4 (1.8) | 46.1 (1.7) |

| Japan | 1682 | 51.2 (0.7) | 53.0 (1.9) | 31.2 (1.4) | 71.6 (1.4) | 36.5 (1.8) |

| Netherlands | 1094 | 45.0 (0.8) | 50.9 (2.2) | 27.9 (2.6) | 69.7 (1.8) | 37.7 (2.6) |

| New Zealand | 7312 | 44.6 (0.4) | 52.2 (1.0) | 34.8 (1.0) | 60.4 (1.0) | 31.2 (0.9) |

| N. Ireland | 1708 | 45.3 (0.6) | 51.0 (1.4) | 40.4 (1.8) | 88.7 (1.0) | 37.4 (1.9) |

| Portugal | 2060 | 46.5 (0.6) | 51.9 (1.5) | 30.4 (1.4) | 54.8 (1.7) | 40.3 (1.5) |

| Spain | 2121 | 45.6 (0.6) | 51.4 (1.7) | 34.7 (1.5) | 41.7 (1.5) | 49.6 (1.8) |

| United States | 5692 | 45.0 (0.4) | 53.0 (1.0) | 44.1 (1.2) | 83.2 (0.9) | 33.2 (1.1) |

| All countries | 62 971 | 42.2 (0.1) | 51.9 (0.3) | 36.6 (0.3) | 57.4 (0.3) | 42.0 (0.3) |

| Comparison among countries | 183.8 (<0.0001)a | 1.2 (0.2) | 20.3 (<0.0001)b | 165.7 (<0.0001)b | 74.4 (<0.0001)b | |

| Lower income | 16 051 | 37.0 (0.2) | 51.1 (0.6) | 37.8 (0.6) | 47.2 (0.6) | 41.8 (0.6) |

| Middle income | 14 811 | 40.3 (0.2) | 52.5 (0.6) | 38.0 (0.6) | 44.5 (0.6) | 51.8 (0.6) |

| Higher income | 32 109 | 45.7 (0.2) | 52.1 (0.4) | 35.2 (0.4) | 69.1 (0.4) | 37.5 (0.4) |

| Comparison lower, middle, higher | 655.5 (<0.0001)a | 1.8 (0.2) | 10.4 (<0.0001)b | 638.6 (<0.0001)b | 177.6 (<0.0001)b | |

Abbreviations: PRC, Peoples' Republic of China; WHO, World Health Organization; WMH, World Mental Health.

Wald F test (P-value).

The χ2 test of independence (P-value).

The distribution of days out of role

The mean number of health-related days out of role in the previous month was 1.2 in the total sample, with a range of 1.0–1.4 across countries in the three income levels (Table 3). The overall mean can be decomposed into 12.8% of respondents who reported any days out of role (14.6% in lower, 10.4% in middle and 13.1% in higher-income countries) and a mean among those with any of 9.6 days (8.3 in lower, 9.3 in middle and 10.3 in higher-income countries). The distribution is skewed to the right, as indicated by the median among those with any days out of role, 4.2 in the total sample (4.0 in lower, 4.3 in middle and 4.3 in higher-income countries) being lower than the mean.

Table 3. Distribution of days totally out of role, by type of country (The WHO WMH surveys).

|

Low income |

Medium income |

High income |

All countries |

Tests |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | s.e. | % | s.e. | % | s.e. | % | s.e. | χ2 | P-value | d.f. | |

| Any days out of role | 14.6 | 0.4 | 10.4 | 0.4 | 13.1 | 0.3 | 12.8 | 0.2 | 29.8 | <0.001 | 2 |

| 1 day | 13.5 | 0.9 | 12.5 | 1.2 | 17.8 | 0.9 | 15.6 | 0.6 | |||

| 2 days | 18.4 | 1.0 | 17.0 | 1.2 | 15.8 | 0.7 | 16.8 | 0.5 | |||

| 3–5 days | 29.4 | 1.2 | 29.6 | 1.6 | 22.2 | 0.9 | 25.7 | 0.7 | |||

| 6–10 days | 17.1 | 1.1 | 14.3 | 1.0 | 13.2 | 0.7 | 14.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 11–20 days | 8.1 | 0.8 | 10.6 | 0.9 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 9.1 | 0.4 | |||

| 21–30 days | 13.5 | 1.0 | 16.1 | 1.2 | 21.9 | 0.8 | 18.3 | 0.6 | 81.2a | <0.001 | 10 |

| |

Mean |

s.e. |

Mean |

s.e. |

Mean |

s.e. |

Mean |

s.e. |

χ2 |

P-value |

d.f. |

| Mean days out of role per month (all respondents) | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 35.1 | <0.001 | 2 |

| Mean days out of role per month (respondents with any day out of role) | 8.3 | 0.3 | 9.3 | 0.3 | 10.3 | 0.2 | 9.6 | 0.2 | 29.7 | <0.001 | 2 |

| Median days out of role per month (respondents with any day out of role) | 4.0 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | |||

Abbreviations: WHO, World Health Organization; WMH, World Mental Health.

Test for difference between distributions of days out of role (among respondents with any) across income groups.

Disorder prevalence estimates

More than half (58.0%) of respondents across countries reported one or more of the disorders considered here. The proportion who reported at least one physical disorder (53.2%) was considerably higher than the proportion who reported any mental disorder (15.4%). The prevalence of having any physical disorder and any mental disorder both increased monotonically with country income level: from 45.6% in low/lower-middle to 52.2% in upper-middle and to 57.4% in high-income countries for any physical disorder; and from 12.1% in low/lower-middle to 15.4% for upper-middle and to 17.0% in high-income countries for any mental disorder. This monotonic increase existed for 11 of the 19 individual disorders, with five others either having their lowest prevalence in low/lower-middle-income countries or having their highest prevalence in high-income countries. The three exceptions were headaches and other chronic pain disorders, both of which had their highest prevalence in upper-middle-income countries, and digestive disorders, with highest prevalence in low/lower-middle-income countries.

The rank order of prevalence estimates across disorders was very similar in the three groups of countries, with rank-order correlations across groups in the range of 0.87–0.97. Chronic pain disorders were among the two most commonly reported disorders in all three groups of countries (21.6–23.7%), headaches among the top two in low/lower-middle- and upper-middle-income countries (14.5–19.4%) and cardiovascular disorders among the top three in upper-middle- and high-income countries (18.2–18.8%). Major depression was the most commonly reported mental disorder in all three groups of countries (4.9–6.2%), followed by specific phobia (4.2–6.0%). Other highly prevalent disorders in all groups of countries were arthritis (12.5–16.6%) and respiratory disorders (11.9–21.9%).

Respondents who reported any disorder had an average of 2.1 disorders. Comorbidity was the norm, with 55.9% of the respondents with a disorder reporting at least two. Odds ratios (ORs) between pairs of disorders were largely positive (94.1% of all the 19 × 18/2=171 ORs between pairs of disorders) and statistically significant (90.0% of all ORs). The ORs were higher (median and interquartile range) among pairs of physical (2.5, 1.9–3.0) and mental (7.2, 4.0–8.7) disorders than between physical–mental pairs (2.0, 1.4–2.6). Similar patterns existed in each of the three groups of countries (detailed results of all ORs are available on request).

Mean days out of role per year varied by condition (Table 4). Individuals with panic (42.9), PTSD (42.7) and bipolar disorder (41.2) had the highest mean numbers of days out of role. Trends were similar across type of countries. Correlations between mean days out of role across conditions were high in each of the three income groups (Spearman rank-order correlations in the range 0.62–0.77). PTSD, panic and generalized anxiety disorder were among the top six conditions with highest mean days out of role in all three income groups. Individuals with any disorder had an average of 24.2 more days out of role in a year (31.1 days those with any mental, 24.5 those with any physical) than those with no conditions.

Table 4. Prevalence of the disorder and mean number of days totally out of role DOR per year, by type of country (The WHO WMH surveys).

|

Lower income countries |

Medium income countries |

Higher income countries |

All countries |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder | Prevalence (%) | s.e. (%) | Mean yearly DOR | s.e. Mean | Prevalence (%) | s.e. (%) | Mean yearly DOR | s.e. Mean | Prevalence (%) | s.e. (%) | Mean yearly DOR | s.e. Mean | Prevalence (%) | s.e. (%) | Mean yearly DOR | s.e. Mean |

| Depression | 4.9 | 0.2 | 35.8 | 0.9 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 34.8 | 0.9 | 6.2 | 0.1 | 33.7 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 0.1 | 34.4 | 0.4 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.4 | 0.1 | 30.8 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 42.4 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 42.6 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 41.2 | 1.1 |

| Panic disorder | 1.1 | 0.1 | 39.6 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 39.7 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 45.6 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 42.9 | 0.8 |

| Specific phobia | 4.2 | 0.2 | 28.9 | 1.2 | 4.6 | 0.2 | 35.2 | 1.1 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 34.8 | 0.6 | 5.2 | 0.1 | 33.8 | 0.5 |

| Social phobia | 1.1 | 0.1 | 33.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 41.3 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 39.7 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 39.3 | 0.7 |

| GAD | 1.1 | 0.1 | 38.1 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 41.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 39.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 39.8 | 0.8 |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.8 | 0.1 | 29.0 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 27.9 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 33.1 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 30.6 | 0.7 |

| Drug abuse | 0.2 | 0.0 | 40.8 | 4.8 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 32.1 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 37.8 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 36.6 | 1.3 |

| PTSD | 0.7 | 0.1 | 44.9 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 40.9 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 42.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 42.7 | 0.9 |

| Insomnia | 4.3 | 0.2 | 37.8 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 0.2 | 36.0 | 1.1 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 36.5 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 36.7 | 0.5 |

| Headache or migraine | 14.5 | 0.4 | 29.8 | 0.5 | 19.4 | 0.5 | 29.3 | 0.5 | 11.1 | 0.2 | 32.3 | 0.4 | 13.9 | 0.2 | 30.7 | 0.3 |

| Arthritis | 13.1 | 0.4 | 28.7 | 0.5 | 12.5 | 0.3 | 30.2 | 0.6 | 16.6 | 0.3 | 29.6 | 0.3 | 14.8 | 0.2 | 29.5 | 0.3 |

| Pain | 21.9 | 0.6 | 26.8 | 0.4 | 23.7 | 0.5 | 28.5 | 0.4 | 21.6 | 0.3 | 28.9 | 0.3 | 22.2 | 0.3 | 28.3 | 0.2 |

| Cardiovascular | 11.9 | 0.4 | 29.8 | 0.6 | 18.2 | 0.4 | 29.6 | 0.5 | 18.8 | 0.3 | 27.9 | 0.4 | 16.9 | 0.2 | 28.7 | 0.3 |

| Respiratory | 11.9 | 0.4 | 26.2 | 0.6 | 13.1 | 0.4 | 30.7 | 0.6 | 21.9 | 0.4 | 28.2 | 0.4 | 17.3 | 0.3 | 28.4 | 0.3 |

| Diabetes | 2.5 | 0.2 | 29.4 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 0.2 | 32.1 | 0.9 | 4.9 | 0.2 | 29.8 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 0.1 | 30.3 | 0.5 |

| Digestive | 4.5 | 0.2 | 29.4 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 37.2 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 37.7 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 34.9 | 0.6 |

| Neurological | 0.8 | 0.1 | 37.8 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 39.8 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 35.5 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 37.2 | 1.1 |

| Cancer | 0.4 | 0.1 | 30.4 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 37.2 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 31.5 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 31.9 | 0.7 |

| Any mental disorder | 12.1 | 0.3 | 30.5 | 0.6 | 15.4 | 0.4 | 32.0 | 0.5 | 17.0 | 0.3 | 31.2 | 0.4 | 15.4 | 0.2 | 31.3 | 0.3 |

| Any physical disorder | 45.6 | 0.6 | 23.7 | 0.3 | 52.2 | 0.7 | 24.8 | 0.3 | 57.4 | 0.5 | 24.7 | 0.2 | 53.2 | 0.3 | 24.5 | 0.1 |

| Any disorder | 49.8 | 0.6 | 23.5 | 0.3 | 56.8 | 0.6 | 24.5 | 0.3 | 62.5 | 0.5 | 24.4 | 0.2 | 58.0 | 0.3 | 24.2 | 0.1 |

| All respondents | 14.8 | 0.6 | 11.8 | 0.6 | 16.4 | 0.5 | 15.0 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Respondents with any day out of role (Median and s.e. Median) | 101.3 | 3.5 | 113.6 | 3.8 | 125.4 | 2.8 | 116.2 | 1.9 | ||||||||

| Respondents with any day out of role (Mean and s.e. Mean) | 48.7 | 2.4 | 52.3 | 1.2 | 52.3 | 0.1 | 51.1 | 0.1 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: DOR, days out of role; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; WHO, World Health Organization; WMH, World Mental Health.

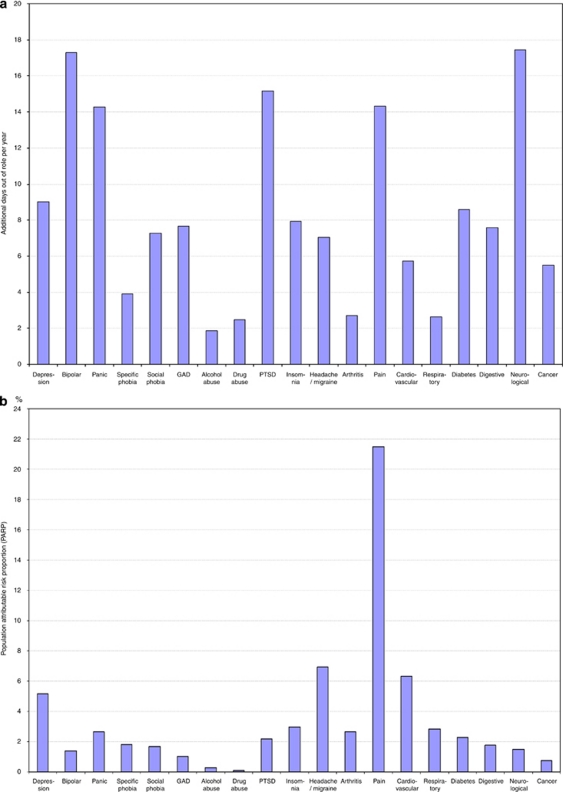

Table 5 shows the additional days totally out of role in a year among respondents with a disorder (individual-level effect), adjusting by age, gender, marital status and employment as well as the number and type of comorbid disorders. The most disabling conditions were bipolar disorder (36.5 additional days), neurological disorders (33.7) and panic (24.3) in lower-income countries, generalized anxiety disorder (24.6 additional days), bipolar (23.4), neurological (18.6) and panic (17.6) in middle-income countries and pain (19.6 additional days), digestive (16.6) and PTSD (16.2) in higher-income countries. Rank correlations of individual effects of the conditions were low across country type (from 0.12 to 0.26). Interactions were found to be sub-additive for most disorders in all three income groups: the incremental increase in days out of role is smaller when a disorder occurs comorbidly compared with when the same disorder occurs in isolation (results are not shown but available on request).

Table 5. Additional yearly days totally out of role (‘individual effects') and PARPs for each condition considered, according to type of country (The WHO WMH surveys)a.

|

Lower income countries |

Medium income countries |

Higher income countries |

All countries |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Additional days |

PARP |

Additional days |

PARP |

Additional days |

PARP |

Additional days |

PARP |

|||||||||

| Mean | s.e | % | s.e. (%) | Mean | s.e. | % | s.e. (%) | Mean | s.e. | % | s.e. (%) | Mean | s.e. | % | s.e. (%) | |

| Depression | 13.1 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 3.1 | 14.7 | 4.1 | 9.7 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 9.0 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 1.4 |

| Bipolar disorder | 36.5 | 15.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 23.2 | 9.6 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 9.6 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 17.3 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| Panic disorder | 24.3 | 12.9 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 17.7 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 11.7 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 14.3 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 0.6 |

| Specific phobia | −6.6 | 5.2 | −2.6 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Social phobia | 5.7 | 10.0 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 9.0 | 8.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 7.5 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 7.3 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 |

| GAD | 13.5 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 24.6 | 8.4 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 7.6 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 7.7 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Alcohol abuse | −2.8 | 7.2 | −0.5 | 1.3 | 8.2 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 1.2 | −0.3 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Drug abuse | 14.7 | 13.9 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 12.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| PTSD | 15.3 | 11.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | −1.1 | 9.5 | −0.1 | 1.0 | 16.2 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 15.2 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 0.5 |

| Insomnia | 5.7 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 9.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 7.9 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| Headache or migraine | 10.0 | 3.6 | 11.7 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 10.7 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 7.1 | 1.5 | 6.9 | 1.5 |

| Arthritis | 6.1 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 5.6 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 1.8 |

| Pain | 0.9 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 11.0 | 2.4 | 21.8 | 5.2 | 19.6 | 2.1 | 25.7 | 2.9 | 14.3 | 1.5 | 21.5 | 2.3 |

| Cardiovascular | 2.7 | 6.7 | 2.5 | 6.2 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 2.7 | 7.6 | 2.8 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 6.3 | 2.3 |

| Respiratory | 10.7 | 3.0 | 9.2 | 2.9 | −1.1 | 2.6 | −1.2 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1.4 |

| Diabetes | 4.0 | 6.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 9.6 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 8.6 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| Digestive | −4.3 | 4.8 | −1.5 | 1.8 | −0.4 | 4.0 | −0.2 | 1.5 | 16.6 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| Neurological | 33.7 | 23.0 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 18.6 | 7.0 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 15.3 | 7.4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 17.4 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| Cancer | 19.4 | 17.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | −4.2 | 12.9 | −0.3 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| All disorders | 15.3 | 1.9 | 58.1 | 5.7 | 12.5 | 1.7 | 59.2 | 7.2 | 18.4 | 0.8 | 66.6 | 2.6 | 16.5 | 0.7 | 62.2 | 2.1 |

| All mental | 10.5 | 3.1 | 13.7 | 4.3 | 12.8 | 2.3 | 20.7 | 3.1 | 11.3 | 1.7 | 16.0 | 2.2 | 11.9 | 1.4 | 16.5 | 1.8 |

| All physical | 12.6 | 3.1 | 42.7 | 8.3 | 9.3 | 1.9 | 39.9 | 7.9 | 16.3 | 1.0 | 52.7 | 3.4 | 14.1 | 0.8 | 47.6 | 2.7 |

Abbreviations: GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; PARP, population attributable risk proportion; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; WHO, World Health Organization; WMH, World Mental Health.

Additional to those estimated for the average individual without the disorder.

In Table 5, the population attributable risk proportion (PARP) of days totally out of role for each condition is also presented. Pain disorders contribute the highest proportion (21.5% on average), followed by headache/migraine (6.9%), cardiovascular (6.3%) and depression (5.1%). For each condition, PARPs tended to be fairly similar across country types, especially between lower- and middle-income countries (Spearman correlations 0.32).

Individual effects and PARPs for all countries combined are presented in Figure 1. The figure clearly shows that the most impacting disorders according to their individual-level effect—most notably neurological, bipolar and pain disorders—(Figure 1a) are quite different from those that have the most impact at the societal level—pain, cardiovascular and depression (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Yearly days totally out of role because of each of the 19 health conditions considered: (a) Among those suffering from the condition (‘individual effect'); and (b) population attributable risk proportion (PARP). All countries: WHO World Mental Health surveys.

Discussion

A number of limitations must be considered before interpreting our results. First, only a restricted set of the most common conditions was included in the analysis and some were pooled to form larger disorder groups. Some burdensome conditions, such as dementia and psychosis, were not included. Although the conditions that we did consider and include were among those most commonly reported in previous population studies,5 an expansion and disaggregation of these conditions is clearly needed in future studies. Second, diagnoses of chronic physical conditions were based on self-reports. Prior research has demonstrated reasonable correspondence between self-reported chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and asthma, and general practitioner records,32 but some bias might account for the generally higher prevalence estimates of these conditions in developed than developing countries. Likely, higher rates of medical treatment and detection in developed countries artificially inflate prevalence country differences. Third, we only considered the days out of role that the respondents reported they were totally unable to do their work or usual activities. It is common that individuals perform their role activities less or worse than expected (for example, presenteeism);33 therefore, information about days out of role underestimates total productivity loss. Finally, to increase validity of self-reporting, we assessed restriction of activities in the 30 days previous to the interview and then projected the numbers in this recall interval to the whole year, improving the comparability with published literature.5 But some mismatch between severity of the disease and its prevalence may exist; for more episodic conditions, this recall period might have missed a severe exacerbation present in the previous year but not in the month before the interview. Because of the relative large number of events assessed, we expect this to cancel out with the opposite situation and overall not affect our estimates.

Within the context of these limitations, we identified a number of disorders that cause a great deal of disability. For the overall sample (Table 4), sufferers of bipolar disorder, PTSD and panic disorder have the highest disability, followed closely by those with generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia. These results show that mental disorders are among the most strongly associated with productivity loss. This finding is broadly consistent with previous studies.34 Nevertheless, as comorbidity is so frequent, and especially so for mental disorders, the observed associations in previous studies, which failed to adjust adequately for comorbidity, could have been due not to the particular conditions themselves, but to their high comorbidity. This possibility was addressed in the analysis reported here by controlling for comorbidity. In Table 5 (individual effect), we observe that the rank ordering of disorders in terms of relative impacts on days out of role change when we adjust for comorbidity. It is consequently important to consider comorbidity in assessing the relative effects of particular disorders on days out of role.

Our results show that the 19 health conditions considered in our study account for almost two-thirds of all days of role in the general populations of the countries studied (PARP=62.2%). Physical conditions accounted for 47.6% and mental disorders for 16.5%. It should be noted that the physical conditions include neurological disorders (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and stroke), pain conditions (including severe headache/migraine) and insomnia. If insomnia was considered a mental disorder instead of a physical disorder, mental disorders would account for up to 20.3% of days out of role (data not shown, but available from the authors). Pain conditions are disabling and highly prevalent and they are, by far, the most important contributor to days totally out of role in the population. Also, cardiovascular disorders, depression and migraine are major contributors to population-level days out of role. These conditions should be prioritized in trying to improve the productivity of our societies. Nonetheless, although PARPs indicate the theoretical proportion of outcome events that could be avoided if the exposure (the disorders in our study) was completely eliminated, and are useful for identifying the burdensome targets for population intervention, it should be borne in mind that disability days avoided by removing one disorder might limit the opportunity of avoiding the same days by removing another condition.35

With a few exceptions, the results presented in this study are similar across the type of countries studied. We had anticipated that cultural, social and economic differences could modulate the association of disorders with days out of role. First, the differences across type of countries in the average proportion of individuals reporting days they were totally unable to carry out normal activities were small. Nevertheless, the mean number of yearly days lost among those with days out of role tended to vary more across type of country. These differences might be because of not only a higher prevalence of disorders, but also a more developed welfare system in higher income countries. Some country differences, nevertheless, deserve further research.

Implications

A first implication is the identification of the relative contribution of different common disorders to the population loss of productivity. Lowering the impact of common and disabling conditions, such as pain, migraine, as well as cardiovascular and depression, would have major productivity returns. If we take into account that indirect costs are usually higher than direct medical and social services costs to care for disorders,6, 36, 37 prevention and treatment of these disorders may be cost effective.

Another implication is that interactions were found to be sub-additive in the best-fitting model. This does not mean that comorbidity is not highly disabling. On the contrary, there is clear evidence of its high burden.38 But it does mean that disability increases at a decreasing rate when comorbid conditions exist. This finding has an important implication for the prevention of disability: addressing only one disorder (treatment or prevention) when it coexists with other disorders will render a less effective outcome than addressing all the coexisting conditions.39

Acknowledgments

The analysis for this paper was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the Mental Health Burden Study (Contract number HHSN271200700030C), the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, the Eli Lilly & Company Foundation, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Shire. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The Chinese World Mental Health Survey Initiative is supported by the Pfizer Foundation. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999–01042; SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000–158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The Israel National Health Survey is funded by the Ministry of Health with support from the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (LEBANON) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), Fogarty International, Act for Lebanon, anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche and Novartis. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria) and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708) and the John W Alden Trust.

Dr Kessler has been a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Kaiser Permanente, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire Pharmaceuticals and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly & Company, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has had research support for WMH and other epidemiological studies from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer and Sanofi-Aventis. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ACOEM Guidance Statement Healthy workforce/healthy economy: the role of health, productivity, and disability management in addressing the nation's health care crisis: why an emphasis on the health of the workforce is vital to the health of the economy. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:114–119. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318195dad2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, Collins SR, Doty MM, Ho A, Holmgren A. Health and productivity among US workers. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2005;856:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhrcke M, Arce RA, McKee M, Rocco L. Economic Costs of Ill Health in the European Region. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, World Health Organization: Copenhaguen; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loeppke R, Taitel M, Haufle V, Parry T, Kessler RC, Jinnett K. Health and productivity as a business strategy: a multiemployer study. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:411–428. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a39180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, Stang PE, Ustun TB, Von Korff M, et al. The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andlin-Sobocki P, Jonsson B, Wittchen HU, Olesen J. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12 (Suppl 1:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff MR.Global perspectives on mental-physical comorbidityIn: Von Korff MR, Scott KM, Gureje O (eds).Global Perspectives on Mental-Physical Comorbidity in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys Cambridge University Press: New York, NY; 20091–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stang PE, Brandenburg NA, Lane MC, Merikangas KR, Von Korff MR, Kessler RC. Mental and physical comorbid conditions and days in role among persons with arthritis. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:152–158. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195821.25811.b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Data & statistics, country groups by incomeAvailable at: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications , 2007

- Heeringa SG, Wells JE, Frost H, Mneimneh ZN, Chiu GT, Sampson NA, et al. Sample designs and sampling proceduresIn: Kessler RC, Üstün TB (eds).The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders Cambridge University Press: New York; 200814–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pennell BE, Mneimneh ZN, Bowers A, Chardoul S, Wells JE, Viana MC, et al. Implementation of the World Mental Health Surveys. Chapter 3. Part I. MethodsIn: Kessler RC, Üstün TB (eds).The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders Cambridge University Press: New York; 200833–57. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness J, Pennell BE, Villar A, Gebler N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bilgen I.Translation procedures and translation assessment in the World Mental Health Survey InitiativeIn: Kessler RC, Üstün TB (eds).The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders Cambridge University Press: New York; 200891–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, et al. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Health, United States, 2004. US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Schiller JS. Summary health statistics for the US population: National Health Interview Survey, 2000. Vital Health Stat 10. 2003;214:1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M, Stewart-Brown S, Fletcher L. Estimating health needs: the impact of a checklist of conditions and quality of life measurement on health information derived from community surveys. J Public Health Med. 2001;23:179–186. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MM, Stabile M, Deri C. What Do Self-Reported, Objective Measures of Health Measure? National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Crane PK, Alonso J, Vilagut G, Angermeyer MC, Bruffaerts R, et al. Modified WHODAS-II provides valid measure of global disability but filter items increased skewness. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:1132–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO WHODAS IIAvailable at: http://www.who.int/icidh/whodas/index.html . Accessed 26 February 2010.

- Vazquez-Barquero JL, Vazquez Bourgon E, Herrera Castanedo S, Saiz J, Uriarte M, Morales F, et al. Versión en lengua española de un nuevo cuestionario de evaluación de discapacidades de la OMS (WHO-DAS-II): fase inicial de desarrollo y estudio piloto. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2000;28:77–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ormel J, Demler O, Stang PE. Comorbid mental disorders account for the role impairment of commonly occurring chronic physical disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:1257–1266. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000100000.70011.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki DA, Irwin D, Reblando J, Simon GE. The accuracy of self-reported disability days. Med Care. 1994;32:401–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199404000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA, Loeppke R, McKenas DK, Richling DE, et al. Using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:S23–S37. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000126683.75201.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O.The pattern and nature of mental-physical comorbidity: specific or generalIn: Von Korff MR, Scott KM, Gureje O (eds).Global Perspectives on Mental-Physical Comorbidity in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA; 200951–83. [Google Scholar]

- Seber GAF, Wild CL. Nonlinear Regression. Wiley: New York; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23:525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer-Verlag: New York; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute inc.(Copyright 2002-2003) SAS/STAT software, version 9.1 for Windows. SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients' self- reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1407–1417. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson K, Andrews G. Common mental disorders in the workforce: recent findings from descriptive and social epidemiology. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:63–75. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polder JJ, Achterberg PW. Cost of Illness in the Netherlands. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment: Bilthoven, The Netherlands; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K, Armstrong B. An overview of methods for calculating the burden of disease due to specific risk factors. Epidemiology. 2006;17:512–519. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000229155.05644.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DP, Miller LS. Health economics and cost implications of anxiety and other mental disorders in the United States. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;34:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit F, Cuijpers P, Oostenbrink J, Batelaan N, de Graaf R, Beekman A. Costs of nine common mental disorders: implications for curative and preventive psychiatry. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006;9:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Hollenbeak CS, Weiner M, Ten Have T, Tang SS. Effect of unrelated comorbid conditions on hypertension management. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:578–586. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-8-200804150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber M, McLaughlin KA, et al. Twelve-month prevalence and severity of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A)in press).