Abstract

Motivation: Assembling genomes from short read data has become increasingly popular, but the problem remains computationally challenging especially for larger genomes. We study the scaffolding phase of sequence assembly where preassembled contigs are ordered based on mate pair data.

Results: We present MIP Scaffolder that divides the scaffolding problem into smaller subproblems and solves these with mixed integer programming. The scaffolding problem can be represented as a graph and the biconnected components of this graph can be solved independently. We present a technique for restricting the size of these subproblems so that they can be solved accurately with mixed integer programming. We compare MIP Scaffolder to two state of the art methods, SOPRA and SSPACE. MIP Scaffolder is fast and produces better or as good scaffolds as its competitors on large genomes.

Availability: The source code of MIP Scaffolder is freely available at http://www.cs.helsinki.fi/u/lmsalmel/mip-scaffolder/.

Contact: leena.salmela@cs.helsinki.fi

1 INTRODUCTION

Present high-throughput sequencing machines can produce hundreds of millions of short reads in a single run. Initially, this technology was targeted at resequencing applications but is nowadays also deployed in de novo sequencing projects. Apart from single reads, the sequencing machines can also produce mate pairs, i.e. pairs of reads whose approximate distance in the target genome is known. Although there are good methods to assemble reads produced by the older Sanger technology, new approaches are needed to deal with data from the second-generation sequencing machines, because the characteristics of the data like read length and sequencing errors are different (Pop, 2009).

In a de novo sequencing project, the read data is typically first quality trimmed and filtered to ensure high-quality data for subsequent processing. A method to correct sequencing errors may also be used. The next step is to assemble the reads into contigs, which are gapless sequences of nucleotides. In the last step, the contigs are ordered into scaffolds based on mate pair reads (Pop, 2009).

Here we consider the scaffolding problem. The input to the scaffolding problem is the contigs produced by a contig assembler, the mappings of the mate pair reads to the contigs and the insert sizes of the mate pair libraries. The objective is to find a linear ordering of the contigs, which maximizes the number of mate pairs whose pairwise distance equals the insert size. In practise, a linear ordering of all the contigs is not achieved, because the data may be incomplete and the organism may have several chromosomes. Instead each contig is assigned to a scaffold and given an orientation and position within the scaffold.

Kececioglu and Myers (1995) have shown that even determining the orientation of the contigs is NP-hard. Therefore, all practical methods to solve the scaffolding problem use heuristics and achieve only an approximate solution.

Many assemblers like Velvet (Zerbino and Birney, 2008), Allpaths (Butler et al., 2008) and SOAPdenovo (Li et al., 2010) contain a scaffolding module. Some stand-alone scaffolders have also been developed. Bambus (Pop et al., 2004) is designed for Sanger data, and SOPRA (Dayarian et al., 2010) and SSPACE (Boetzer et al., 2011) are developed for second-generation sequencing data. Bambus and SSPACE are based on a greedy method, whereas SOPRA relies on statistical optimization and partitioning the scaffolding problem. Our new approach uses a partitioning scheme similar to SOPRA but unlike SOPRA we restrict the size of the partitions and thus we can solve the subproblems exactly with mixed integer programming.

The rest of the article is outlined as follows. In Section 2, we present a theoretical framework for scaffolding based on mixed integer programming and partitioning the scaffolding problem. Section 3 presents a practical implementation of this framework. We compare the new scaffolder to SOPRA and SSPACE in Section 4. Finally, we conclude in Section 5.

2 ALGORITHM

The input to a scaffolder is a set of contigs produced by an assembler and a set of mate pairs. First, we map the mate pairs to the contigs. This yields links between contigs that we represent as a graph. The graph is then partitioned into subproblems, which we solve with mixed integer programming. Finally, we combine the solutions of the subproblems to solve the whole scaffolding problem. Each of these tasks is discussed in more detail below. In Section 3, we address practical issues in implementing our approach.

2.1 Scaffolding graph

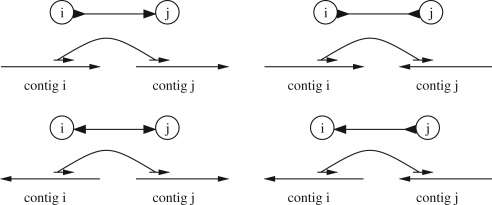

The input to the scaffolding problem can be represented as a bidirected graph called the scaffolding graph. Each contig is represented by a node in the graph. There is an edge between two contigs if there are mate pairs linking them. The edge is directed at both endpoints indicating the orientation of the contigs with regard to each other. Figure 1 shows the four possible ways of linking two contigs. Here the mate pair ends are oriented as in SOLiD data, where both reads of the pair are from the same strand of the genome.

Fig. 1.

The four possible ways of linking two contigs with a mate pair and the bidirected edge representing each case.

Several mate pairs can induce the same edge in the scaffolding graph. The total number of these mate pairs is the support sk of the edge k. These mate pairs are used to estimate the distance dk between the two contigs.

The scaffolding problem can now be formulated as removing a set of edges with minimum combined support from the scaffolding graph such that each node can be assigned a position and orientation that satisfy the constraints imposed by the remaining edges. Each scaffold can then be constructed in two equivalent ways: the other way can be obtained by reversing the whole scaffold.

2.2 Mixed integer programming formulation

In this section, we will develop a mixed integer programming (MIP) formulation for the scaffolding problem. As a convention, we will use italic type to denote variables and roman type to denote constants for those quantities that are present in the MIP formulation. There are n contigs. Let us denote the length of contig i by ai. Let L be an estimate of the upper bound of possible scaffold length (e.g. an estimated upper bound of the length of the entire genome or the longest chromosome).

The solution to the MIP problem will assign values to the following variables. For each contig i (1≤i≤n), we have two integer-valued variables:

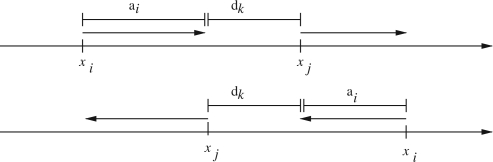

xi∈{1,…, L}: the location of contig i in its scaffold. The location is always the position that aligns with the beginning of the contig. So if the contig aligns to the scaffold in reverse, the location is still the position where the beginning of the contig aligns. See Figure 2 for examples.

oi∈{0, 1}: the orientation of the contig, 0 meaning reverse orientation and 1 forward orientation.

Fig. 2.

The two possible placements of contigs i and j when an edge with orientation corresponding to the top left case in Figure 1 is used in a scaffolding. The top figure shows the case when both contigs are forward oriented and the bottom one shows the case when they are reverse oriented.

Additionally, there is one real-valued variable for each edge in the scaffolding graph:

Ik∈[0, 1]: how well the distance constraint imposed by edge k is satisfied. Ik=1 means that in the solution the distance between contigs of edge k is exactly dk.

We have thus 2n+m variables in total where m is the number of edges in the scaffolding graph.

Each edge k imposes a set of constraints. We give here the constraints for an edge where the two contigs, i and j, are oriented and positioned with regard to each other according to the top left case in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows the two possible placements of the contigs in a scaffold so that the mate pairs are satisfied. We see that here both contigs are either forward oriented or reverse oriented. Thus, oi=oj and we get the following constraints:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where the indicator variable Ik is used to relax the constraints because if the mate pairs are not satisfied in the solution, then the orientations may not match either.

From the top case of Figure 2, we see that the following should hold when both contigs are forward oriented:

We get the following relaxed constraints:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where C is a large enough constant to relax the constraints if either this edge is not included in the solution or the two contigs are reverse oriented. A good choice for C is 2L as xi≤L and xj≤L. Similarly, we get the relaxed constraints for the case where both contigs are reverse oriented (see bottom of Fig. 2):

| (5) |

| (6) |

The constraints for edges corresponding to the other three cases shown in Figure 1 are derived similarly. For each edge, we thus get six constraints corresponding to Equations (1-6). In total, we get 6m constraints where m is the number of edges in the scaffolding graph.

When defining the constraints imposed by edge k, we allowed the distance dk to vary by C (1 − Ik). Our objective is to minimize the amount by which we need to stretch these constraints:

where the sum is over all edges in the scaffolding graph. This is equivalent to the objective function:

| (7) |

where again the sum is over all edges in the scaffolding graph. Note that if Ik were integer-valued, this would correspond to maximizing the number of satisfied mate pairs.

The solution to the MIP problem assigns values to the variables xi, oi and Ik. We then remove from the scaffolding graph those edges that are stretched or contracted by >1000 bp (i.e. Ik is not close to 1). Each connected component of the graph then forms a scaffold and the variables xi and oi give the position and orientation of each contig i within its scaffold.

The above formulation allows two contigs to be positioned in the solution so that they overlap. As post-processing, we detect such overlapping contigs and remove one of them from the scaffold if the overlap is long and the overlapping sequences of the contigs are not similar.

2.3 Partitioning the scaffolding problem

Dayarian et al., (2010) noticed that the scaffolding problem can be partitioned into subproblems that can be solved independently. If the removal of a contig divides the scaffolding graph into two components, then the scaffolding can be solved independently for these two components both of which also include the removed node. Since the two parts of the graph only share one contig, the independent solutions can be easily combined. In graph theoretical terms, this corresponds to dividing the scaffolding graph into its biconnected components, and the contigs whose removal disconnects the graph are the articulation nodes.

If there are no errors in mate pairs or their mappings, all contigs longer than the insert length of the mate pair library are articulation nodes in the scaffolding graph, because no mate pair spans over them. Thus, long contigs should divide the other contigs into those that come before them and those that come after. In real data, there are chimeric mate pairs and mate pairs that map to several locations in the genome. Therefore, not all long contigs in real data are articulation nodes.

When combining the scaffolds from independent solutions, overlaps between contigs have to be observed. If combining two solutions would cause two contigs with sequence similarity <90% to overlap, we do not combine the solutions. Instead we keep one solution as it is and remove the contig corresponding to the articulation node from the other solution and split that solution into two scaffolds, those contigs that are placed before the removed one and those that are placed after.

3 IMPLEMENTATION

3.1 General

MIP Scaffolder is implemented as a set of C++ programs. We use Lemon graph library (http://lemon.cs.elte.hu/) to implement the scaffolding graph and lp_solve (http://lpsolve.sourceforge.net/) to solve the MIP problems.

As input MIP Scaffolder takes the contigs as FASTA files and the alignments of the mate pairs to the contigs as SAM files. MIP Scaffolder can use several mate pair libraries with different insert sizes simultaneously. The output of MIP Scaffolder is the scaffolds in a FASTA file.

3.2 Filtering mate-pair mappings

We first use a read mapper like the readaligner tool by Mäkinen et al., (2010) to map the mate pairs to the contigs. For further processing, we use only those mate pairs whose both ends map to a unique position in the contig collection.

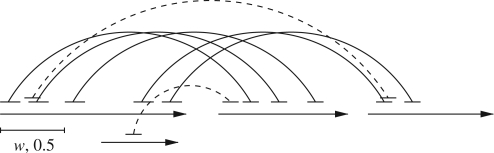

To improve the quality of the mate pair mappings, we filter the mappings so that we only keep mappings that are consistent with other mate pairs mapping to approximately the same location. We call a mate pair mapping (w, p)-consistent if for both ends of the mate pair the following holds: if a mate pair end maps to a contig, then there exists a window of length w on this contig such that if in total r mate pair ends map into the same window and link the contig to the same direction, then at least p· r of all these mate pairs link the same pair of contigs as the original mate pair. We only keep the mate pairs mappings that are (w, p)-consistent for some w and p which are parameters of our method. Figure 3 shows examples of (w, 0.5)-consistent and inconsistent mate pair mappings. Consistent mate pair mappings can be found by sliding a window of length w on each contig. If the window contains r mappings and p· r of these link the same pair of contigs, then the p· r mate pair ends are marked consistent. We then scan all the mate pair mappings and keep those whose both ends are marked consistent.

Fig. 3.

Examples of (w, 0.5)-consistent and inconsistent mate pair mappings. The arrows denote contigs and the short lines mate pairs. The mate pair ends are connected with arcs. The mate pairs with solid line arcs connecting them are consistent and the mate pairs with dashed line arcs connecting them are not consistent.

Filtering out mate pairs that are not consistent has two benefits. First, it ensures that mate pairs mapping to repeat regions are not used in the scaffolding process even if the repeat region is present only once in the contig collection. If all repeat regions would be present several times, keeping only unique mappings should suffice. Second, the insert length distributions tend to have long tails. Mate pairs whose insert length deviates significantly from the mean may be filtered out allowing us to estimate the distance between contigs more accurately.

3.3 The scaffold graph

To estimate the distance dk associated with an edge k linking two contigs, we use edge bundling (Pop et al., 2004) combined with a maximum likelihood method (Gnerre et al., 2011; Simpson et al., 2009). For each mate pair library, we estimate the mean insert size gmean and the insert size range [gmin, gmax] and using these values we compute minimum and maximum suggested distances between the contigs based on each mate pair. We then find a maximum set of mate pairs such that the intersection of the suggested distance ranges is a non-empty range. The final distance dk is then computed as a maximum likelihood estimate based on the mean insert size.

Contigs from repeat regions complicate the scaffolding process, because they do not have a unique placement in the genome. Like previous approaches (Dayarian et al., 2010), we attempt to recognize such contigs based on their high degree in the scaffolding graph or much higher than expected coverage and remove them from the scaffolding graph. By default, contigs with coverage >2.5 times the average coverage of contigs or degree >50 are classified as repeat contigs. Both thresholds can be adjusted by the user.

3.4 Restricting the size of partitions

If the biconnected components of the scaffolding graph are large, it is not feasible to solve the corresponding MIP problem. Furthermore, solutions to MIP problems of such large partitions often place many contigs so that they overlap with other contigs even if the overlapping sequences are not similar. This complicates the post-processing of the solutions.

Therefore, we restrict the size of the biconnected components by using a suitable subgraph of the scaffolding graph. We use the technique by Westbrook and Tarjan (1992) to keep track of the biconnected components dynamically as new edges are added to the scaffolding graph. We measure the size of a biconnected component by the number of edges. First, we sort the potential edges of the scaffolding graph in decreasing order according to their support sk. We then add the edges to the graph in this order but only if the addition of an edge does not create a too large biconnected component. This allows us to demand high support edges for those parts of the genome that are well sampled by the mate pair library, while also being able to utilize lower support edges for those parts of the genome that have a lower coverage in the mate pair library. We show in our experiments that a relatively small threshold for the component size yields the best scaffolding results.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Mate pair libraries and contigs

The read sets used to test our approach are summarized in Table 1. The first two read sets are SOLiD reads from the Escherichia coli DH10B substrain and the Caernorhabditis Elegans genome. The E.coli read set is produced by Applied Biosystems, and we used the filtered subset available at http://hts.rutgers.edu/. This set is quality filtered and trimmed to 35 bp. We used the mean filter distributed with SOPRA to filter the C.elegans read set and kept reads with average quality at least 19 and no indeterminate colors. The third read set is an Illumina paired end library for Pseudomonas syringae and the fourth read set consists of two Illumina mate pair libraries for the human genome. The human Illumina mate pair libraries were first trimmed to 36 bp and then we filtered out all reads where >30% of the bases had quality score ≤10. The statistics in Table 1 are for the filtered sets.

Table 1.

The test datasets

| E.coli | C.elegans | P.syringae |

H.sapiens |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference organism | |||||

| Name | Escherichia coli | Caenorhabditis elegans | Pseudomonas syringae | Homo sapiens | |

| Genome size (Mbp) | 4.6 | 100.3 | 6.1 | 3080 | |

| Dataset | |||||

| Accession number (SRA/ERA) | NA | SRR033650 | ERR005143 | SRR067771 | SRR067773 |

| SRR067777 | SRR067779 | ||||

| SRR067781 | SRR067778 | ||||

| SRR067776 | SRR067786 | ||||

| Read length (bp) | 35 | 25 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Number of reads | 2× 7.4 M | 2× 24 M | 2× 3.6 M | 2× 298.6 M | 2× 342.0 M |

| Coverage | 110× | 10× | 42× | 7× | 8× |

| Spanning coverage | 1930× | 427× | 236× | 223× | 311× |

| Insert size | 1200 | 1785 | 400 | 2300 | 2800 |

| Sequencing platform | SOLiD | SOLiD | Illumina | Illumina | Illumina |

The statistics are given for the sets after trimming and filtering. The spanning coverage is the total coverage of the read pairs and the bases in between them.

We ran the initial contig assembly with Velvet (Zerbino and Birney, 2008). The reads in the C.elegans dataset were too short and the coverage too low to assemble the reads into contigs. We were also not able to assemble contigs for the complete human genome because of memory constraints. Instead we used the wgsim tool distributed with SAMtools (Li et al., 2009) to generate synthetic reads of length 100 from the reference genome and built the contigs based on these reads. For the human genome, the reads were generated and assembled one chromosome at a time to keep the memory requirements on a reasonable level. The coverage of these synthetic reads was 30× for C.elegans. For the human genome, we generated paired reads with insert size 500 and 20× coverage. These reads were not made available for scaffolding.

When running Velvet, we kept contigs >150 bp. We used the following other parameters:

E.coli: hash length 19 and coverage cutoff 6.

C.elegans: hash length 61 and coverage cutoff 6.

P.syringae: hash length 21 and coverage cutoff 6.

H.sapiens: hash length 57, coverage cutoff 6, and expected coverage 20, no scaffolding.

The E.coli dataset was in color space and we used the contig translation of SOPRA to get contigs in base space. For the other datasets, the reads used to build the contigs were in base space and so we could directly use the contigs produced by Velvet. The statistics of the produced contigs are included in Tables 3–6.

Table 3.

The length and validation statistics of scaffolds produced from the E.coli data set by the scaffolders

| Scaffolder | Number of scaffolds | N50 (bp) | Total length (bp) | Genome coverage | Scaffold coverage | Normalized N50(bp) | Validity at 10kb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With gaps | No gaps | With gaps | No gaps | ||||||

| Contigs | 4341 | – | 1499 | – | 4 362 035 | 0.922 | 0.998 | 1496 | – |

| SOPRA | 168 | 203 090 | 185 290 | 4 840 884 | 4 354 534 | 0.912 | 0.988 | 185 227 | 0.910 |

| MIP Scaffolder | 207 | 182 666 | 170 864 | 4 558 212 | 4 327 789 | 0.889 | 0.968 | 170 796 | 0.972 |

When computing colinear chaining to obtain genome coverage, scaffold coverage and normalized N50 values, gaps were restricted to at most 2000 bp.

Table 6.

The length and validation statistics of scaffolds produced from the H.sapiens dataset by the scaffolders

| Scaffolder | Number of scaffolds | N50 (bp) | Total length (bp) | Genome | Scaffold | Normalized | Validity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With gaps | No gaps | With gaps | No gaps | ||||||

| Contigs | 349 514 | – | 18 994 | – | 2 785 310 070 | 0.863 | 0.959 | 18 185 | – |

| SSPACE | 97 525 | 348 941 | 348 566 | 2 834 193 333 | 2 783 020 651 | 0.640 | 0.719 | 179 418 | 0.869 |

| MIP Scaffolder | 83 909 | 328 665 | 325 444 | 2 823 814 726 | 2 776 643 640 | 0.684 | 0.769 | 190 008 | 0.870 |

When computing colinear chaining to obtain genome coverage, scaffold coverage and normalized N50 values, gaps were restricted to at most 5000 bp.

4.2 Evaluation of scaffolds

The produced scaffolds were compared for the length of the scaffolds and for their correctness. For length comparison, we used the N50 measure as well as the total length of the scaffolds.

We evaluated the correctness of the scaffolds as follows. Using swift by Rasmussen et al. (2006), we searched for maximal approximate local matches between the scaffold and the genome sequence. With E.coli and P.syringae, we used parameters 11 for the seed length, 0.05 for the maximum error level and 30 for the minimum length of a maximal match. With C.elegans, we used the same seed length, 0.02 for the maximum error level and 35 for the minimum length of a maximal match. With the human scaffolds, we used 0.01 for the maximum error level, and 100 for the minimal length of a maximal match. This produced a set of tuples each representing a match between a substring range of scaffold and substring range of genome. To obtain an alignment for the whole scaffold inside the genome, we implemented the colinear chaining algorithm (Abouelhoda, 2007) that finds a subset of the tuples that retains the linear order in both source (scaffold) and target (genome), and maximizes the overall coverage of the source (scaffold). Additionally, we restricted the length of gaps in the colinear chaining algorithm to 2000 bp on the E.coli and P.syringae datasets and to 5000 bp on the C.elegans and human datasets. This way we could obtain a reliable alignment without resorting into laborious sequence-level dynamic programming.

Three measures were computed based on the colinear chaining. Genome coverage denotes the proportion of positions inside the genome taking part into the alignment. Scaffold coverage denotes the proportion of positions inside scaffolds taking part into the alignment. We also extracted those parts of the scaffolds that took part into the alignment and repeated the colinear chaining computation recursively for the remaining part until no parts having a maximal local approximate match remained. Finally, we computed the N50 length statistic for all extracted parts. We call this N50 value the normalized N50 statistic. Note that the extracted parts of scaffolds do not contain gaps and so the normalized N50 statistic should be compared to the N50 value computed on the complete scaffolds excluding gaps.

The validity of scaffolds was additionally measured similarly to Gnerre et al. (2011). Pairs of sequences separated by a given distance were extracted randomly from the scaffolds. These pairs were then mapped to the reference and we measured the proportion of pairs whose orientation matched and distance was within 10% of the given distance. The validity of contigs was not measured in this fashion as they were not long enough.

4.3 Parameters and runtime of the scaffolders

For the E.coli, C.elegans and P.syringae datasets, we used readaligner (Mäkinen et al., 2010) to map the mate pairs to contigs and for the human dataset we used SOAP2 (Li et al., 2009). For the E.coli and P.syringae datasets, the results for SOPRA are for the version which is integrated with Velvet and thus directly uses the placement of reads as designated by Velvet. We allowed at most two edit operations (mismatches and indels) when running readaligner and at most three mismatches when running SOAP2. We were able to map 91% of the E.coli reads, 87% of the C.elegans reads and 87% of the P.syringae reads. For the human dataset, SOAP2 reported a unique match for 70% of the reads.

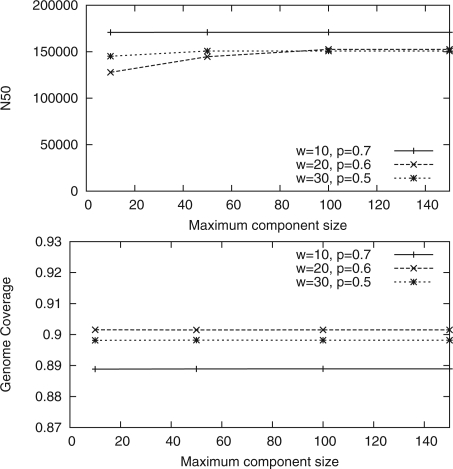

We tried several parameter combinations for MIP Scaffolder. Figure 4 shows how the N50 value and the genome coverage of the scaffolds for the E.coli dataset evolve as we vary w and p when determining (w,p)-consistent mappings. The longest scaffolds are produced with fairly loose filtering but the loosest filtering also gives less accurate scaffolds. Figure 5 shows how the N50 value and the genome coverage evolve when the maximum size of the biconnected component is varied. Here, we notice that the maximum size of the component does not affect the scaffold lengths or correctness much. For the analysis of the scaffolds, we used (10, 0.7)-consistent mappings and maximum component size 100.

Fig. 4.

The effect of filtering (w,p)-consistent mappings for the E.coli dataset. Here we used the maximum component size of 100 edges.

Fig. 5.

The effect of maximum component size for (w,p)-consistent mappings for various combinations of w and p for the E.coli dataset.

We similarly experimented with different parameters on the other datasets and chose those parameters that produced longest scaffolds. For the C.elegans dataset, we used (30, 0.75)-consistent read mapping and maximum component size 50, for the P.syringae dataset (30, 0.5)-consistent read mappings and maximum component size 50 and for the human dataset (50, 0.75)-consistent read mappings and maximum component size 50.

We tried several parameters for running SOPRA and show the results for those parameters that gave the longest scaffolds measured by the N50 value. The E.coli and the P.syringae scaffolds were produced with the version of SOPRA that is integrated with Velvet, and the C.elegans and human scaffolds were produced using pregenerated contigs. For the E.coli dataset, we got best results with support threshold (-w) 6. The original paper reports result with support threshold 5 but our scaffolds are slightly longer. This might be due to the stochastic nature of the algorithm which means that even different runs with the same parameters may produce different results. For the C.elegans and P.syringae datasets, we got longest scaffolds with support thresholds 20 and 4, respectively. We could not run SOPRA on the human dataset because it ran out of memory.

SSPACE does not support mate pair libraries from the SOLiD technology and so we ran it only on the P.syringae and human datasets. SSPACE was run with default parameters.

The scaffolders were run on a server with 16 cores operating at 2.93 GHz and 128 GB of memory. Table 2 shows the runtimes of the different scaffolders. We see that MIP Scaffolder is the fastest of the scaffolders except on the human dataset. On the human dataset, MIP Scaffolder spent half of its time preprocessing the read mappings. As further work, we plan to improve the efficiency of this phase.

Table 2.

Runtimes (in hours) of the scaffolders

| E.coli | C.elegans | P.syringae | H.sapiens | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOPRA | 0.17 | 3.12 | 0.03 | – |

| SSPACE | – | – | 0.02 | 9.5 |

| MIP Scaffolder | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.004 | 18.8 |

4.4 Comparison of scaffolds

Tables 3–6 show the length and validation statistics of the scaffolds produced by SOPRA, SSPACE and MIP Scaffolder for the various datasets. We report the scaffold lengths both including gaps and without gaps. The length statistics without gaps are more important, because the statistics with gaps can vary if the insert length of the mate pair library is estimated incorrectly (Pop et al., 2004).

For the E.coli data, SOPRA produces longest scaffolds that are also the most accurate as measured by genome coverage. The validity at 10 kb of these scaffolds is low because SOPRA's estimate of the insert size is not accurate. For the C.elegans data, MIP Scaffolder produces longest scaffolds that are almost as accurate as those produced by SOPRA. On this dataset, we note that scaffolds produced by SOPRA have a higher genome coverage than the contigs which is likely due to our method maximizing the scaffold coverage instead of genome coverage; contigs can be easier aligned to the same region in genome than scaffolds. For the P.syringae data, MIP Scaffolder produces longest scaffolds that are not quite as accurate as those produced by the other methods. We also note that SSPACE performs better than SOPRA on this dataset. For the human scaffolds, the coverage figures are quite low for both MIP Scaffolder and SSPACE. This is partly due to the strict alignment criteria that was used to make running the validation feasible. Also the coverage of the contigs is low for this dataset indicating that a larger portion of the contigs are chimeric. A chimeric contig incorporated into a scaffold breaks the alignment of the scaffold against the reference into two parts of which only the longer one is considered in our validation method when computing genome and scaffold coverage. Structural variation between individuals may also cause lower coverage in the human data as the contigs are built on simulated reads from the reference genome, while the mate pairs are real data. Also validity at 50 kb is low indicating problems with scaffolding.

Table 4.

The length and validation statistics of scaffolds produced from the C.elegans dataset by the scaffolders

| Scaffolder | Number of scaffolds | N50 (bp) | Total length (bp) | Genome coverage | Scaffold coverage | Normalized N50 (bp) | Validity at 10 kb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With gaps | No gaps | With gaps | No gaps | ||||||

| Contigs | 31 419 | – | 14 717 | – | 96 249 755 | 0.943 | 1.000 | 14 717 | – |

| SOPRA | 17 951 | 132 547 | 130 346 | 98 595 934 | 96 243 554 | 0.945 | 0.999 | 130 346 | 0.990 |

| MIP Scaffolder | 10 721 | 189 704 | 187 796 | 98 273 945 | 95 406 856 | 0.933 | 0.986 | 183 891 | 0.973 |

When computing colinear chaining to obtain genome coverage, scaffold coverage and normalized N50 values, gaps were restricted to at most 5000 bp.

Table 5.

The length and validation statistics of scaffolds produced from the P.syringae dataset by the scaffolders

| Scaffolder | Number of scaffolds | N50 (bp) | Total length (bp) | Genome coverage | Scaffold coverage | Normalized N50 (bp) | Validity at 10 kb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With gaps | No gaps | With gaps | No gaps | ||||||

| Contigs | 2251 | – | 6972 | – | 5 925 601 | 0.964 | 0.981 | 6982 | – |

| SOPRA | 568 | 75 224 | 74 724 | 5 987 540 | 5 917 490 | 0.958 | 0.989 | 72 714 | 0.998 |

| SSPACE | 345 | 94 315 | 93 850 | 5 991 990 | 5 910 839 | 0.946 | 0.978 | 93 850 | 0.984 |

| MIP Scaffolder | 188 | 103 598 | 103 352 | 5 990 318 | 5 919 596 | 0.918 | 0.949 | 84 779 | 0.983 |

When computing colinear chaining to obtain genome coverage, scaffold coverage and normalized N50 values, gaps were restricted to at most 2000 bp.

5 CONCLUSION

We have presented MIP Scaffolder which partitions the scaffolding problem into subproblems of restricted size and solves these subproblems exactly with mixed integer programming. We compared MIP Scaffolder to SOPRA and SSPACE on four datasets. On two of the datasets, MIP Scaffolder produced longer scaffolds that are not quite as accurate as those produced by the other two methods. For the human dataset, MIP Scaffolder produced slightly shorter but more accurate scaffolds than SSPACE and on the E.coli dataset SOPRA outperformed MIP Scaffolder. Our experiments also showed that our approach is fast allowing the user to try out different parameter combinations easily to optimize for long scaffolds. It is also possible to optimize for accurate scaffolds if, for example, EST data or the sequence of a close relative species can be used to measure the correctness of scaffolding.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We wish to thank Rainer Lehtonen, Virpi Ahola, Ilkka Hanski, Panu Somervuo, Lars Paulin, Petri Auvinen, Liisa Holm, Patrik Koskinen and Pasi Rastas for insightful discussions about sequence assembly and scaffolding.

Funding: Academy of Finland [Grant numbers 118653 (ALGODAN) and 1140727]; Helsinki Graduate School in Computer Science and Engineering.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Abouelhoda M. Proceedings of SPIRE′07. Vol. 4726. Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. A chaining algorithm for mapping cdna sequences to multiple genomic sequences; pp. 1–13. of LNCS. [Google Scholar]

- Boetzer M., et al. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:578–579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J., et al. ALLPATHS: de novo assembly of whole-genome shotgun microreads. Genome Res. 2008;18:810–820. doi: 10.1101/gr.7337908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayarian A., et al. SOPRA: scaffolding algorithm for paired reads via statistical optimization. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:345. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnerre S., et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:1513–1518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017351108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kececioglu J.D., Myers E.W. Combinatorial algorithms for DNA sequence assembly. Algorithmica. 1995;13:7–51. [Google Scholar]

- Li H. The sequence alignment/map (SAM) format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 2010;20:265–272. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen V., et al. Algorithms and Applications: Essays Dedicated to Esko Ukkonen on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Vol. 6060. Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. Unified view of backward backtracking in short read mapping; pp. 182–195. of LNCS. [Google Scholar]

- Pop M. Genome assembly reborn: recent computational challenges. Brief. Bioinformatics. 2009;10:354–366. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop M., et al. Hierarchical scaffolding with Bambus. Genome Res. 2004;14:149–159. doi: 10.1101/gr.1536204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K., et al. Efficient q-gram filters for finding all epsilon-matches over a given length. J. Comp. Biol. 2006;13:296–308. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2006.13.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J.T., et al. ABySS: a parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res. 2009;19:1117–1123. doi: 10.1101/gr.089532.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook J., Tarjan R.E. Maintaining bridge-connected and biconnected components on-line. Algorithmica. 1992;7:433–464. [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino D.R., Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]