Abstract

Motivation: Research in the biomedical domain can have a major impact through open sharing of the data produced. For this reason, it is important to be able to identify instances of data production and deposition for potential re-use. Herein, we report on the automatic identification of data deposition statements in research articles.

Results: We apply machine learning algorithms to sentences extracted from full-text articles in PubMed Central in order to automatically determine whether a given article contains a data deposition statement, and retrieve the specific statements. With an Support Vector Machine classifier using conditional random field determined deposition features, articles containing deposition statements are correctly identified with 81% F-measure. An error analysis shows that almost half of the articles classified as containing a deposition statement by our method but not by the gold standard do indeed contain a deposition statement. In addition, our system was used to process articles in PubMed Central, predicting that a total of 52 932 articles report data deposition, many of which are not currently included in the Secondary Source Identifier [si] field for MEDLINE citations.

Availability: All annotated datasets described in this study are freely available from the NLM/NCBI website at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/CBBresearch/Fellows/Neveol/DepositionDataSets.zip

Contact: aurelie.neveol@nih.gov; john.wilbur@nih.gov; zhiyong.lu@nih.gov

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research in the biomedical domain aims at furthering our knowledge of biological processes and improving human health. Major contributions toward this goal can be achieved by sharing the results of research efforts with the community, including datasets produced in the course of the research work. While such sharing behavior is encouraged by funding agencies and scientific journals, recent work has shown that the ratio of data sharing is still modest compared with actual data production. For instance, Ochsner et al. (2008) found the deposition rate of microarray data to be <50% for work published in 2007.

Piwowar and Chapman (2007) show that data deposition results in increased citation of papers reporting on data production. While this should serve as an incentive to deposit data and announce it to the community, in a more recent study these same authors (Piwowar and Chapman, 2010) show that data deposition is significantly associated with high-profile journals and experienced researchers. In the course of this work, these authors have found the identification of data deposition statements to be a challenging task that can be addressed using natural language processing and machine learning methods (Piwowar and Chapman, 2008a). Information about the declaration of data deposition in research papers can be used in different ways. First, for data curation: databases such as MEDLINE® use accession numbers for certain databases as metadata that can be searched with PubMed® queries using the [si] field. Journals can benefit from such a tool to check whether their data deposition policies are enforced. This aspect is also important for researchers looking to re-use datasets and build on existing work. Second, for the analysis of emerging research trends: the type of data produced gives indications on current important research topics. In a study based on the analysis of Medical Subject Headings® (MeSH®) indexing, Moerchen et al. (2008) show that such metadata may be used to predict future research trends, including recommendations of main headings to be added to the MeSH thesaurus. Our long-term research interest is in assessing the value of using deposition statements for predicting future trends of data production. The initial step of automatically identifying deposition statements could then lead to an assessment of the need for storage space of incoming data in public repositories. In this study, we aim at identifying articles containing statements reporting the deposition of biological data.

As explained above, the study of data deposition has generated a growing interest in the past few years. In response to a Nature Methods editorial (Anonymous, 2008) describing the deposition of data such as genome sequence or microarrays as ‘routine’, Ochsner et al. (2008) used a manually built query to retrieve articles likely to report the production of microarray data in 2007 publications. They manually analyzed 398 articles reporting the production of microarray data and concluded that only ~50% report deposition of microarray data in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) or other databases. Piwowar and Chapman (2008a) further studied the links existing between microarray data deposition in public repositories (e.g. GEO and ArrayExpress) and reports of data deposition in the literature. They used machine learning to build a query suitable for retrieving research articles in PubMed Central reporting on data deposition. Piwowar and Chapman (2008b) also addressed the classification of articles (at the article level) for data sharing in five databases (GenBank, Protein DataBank, GEO, ArrayExpress, Stanford Microarray Database). The authors compared pattern matching versus machine learning. The best results were obtained with a J48 decision tree on ArrayExpress (96% F-measure), although the corresponding dataset was rather small: 29 documents including 12 positive results. Overall performance on the five databases was 69% F-measure. Kim et al. (2010) compared Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Bayes classifiers for the identification of sentences containing database accession numbers. This task was tailored to the specific need for curation of accession numbers in databases such as MEDLINE. These authors discussed the errors linked to ambiguity of accession numbers with other reference numbers such as PMIDs. However, they did not discuss or investigate the occurrence of accession numbers for purposes other than data deposition. For instance, accession numbers can be given in sentences reporting the re-use of previously deposited data. They can also be used in sentences discussing datasets that were produced separately from the context of the experiments reported in the article. Finally, in an effort to bridge the gap between specific gene or genomic regions and related research articles, Haeussler et al. (2011) show that the extraction of short DNA sequences from full-text articles can be used to automatically map articles to GenBank entries without relying on mentions of gene names or accession numbers.

In our work, we propose to identify articles reporting data deposition through the classification of sentences. The general topics of text classification and specifically sentence classification have been well studied in the past decade (Sebastiani, 2002). In the biomedical domain, many tasks can be approached as a sentence classification problem. Often, the small number of classes studied makes the problem amenable to the use of machine learning methods. For instance, several efforts aiming at the retrieval of text passages as evidence for biological or clinical phenomena performed sentence classification. Demner-Fushman et al. (2005) addressed the classification of MEDLINE abstract sentences between seven clinical outcome categories in order to automatically identify outcome-related information in the medical text. They reported the precision of the top ranked sentence between 50% and 60% depending on category. Kim et al. (2011) used the same dataset for classifying sentences for evidence-based medicine. Their best performance for SVM classification was 81% F-measure obtained for the outcome category of sentences in structured abstracts. Results for unstructured abstracts and other categories were less successful. Polajnar et al. (2011) addressed the identification of MEDLINE abstract sentences denoting protein–protein interaction as a binary classification problem. Using SVM classifiers and protein annotations as features, they reported best F-measure performance of ~70%. While these efforts were limited to abstracts, other work used full-text articles. In the BioCreative II challenge (Krallinger et al., 2008), the interaction sentences subtask required participants to retrieve passages of up to three consecutive full-text sentences providing evidence for protein–protein interaction. The best performing team obtained ~20% precision when automatically extracted passages were compared with evidence sentences manually selected by curators. These results reflect the difficulty of the task of extracting evidence statements from full-text articles.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this study, we are interested in identifying statements declaring the deposition of biological data (such as microarray data, protein structure, gene sequences) in public repositories. In the rest of this article, we will refer to such statements as ‘deposition statements’. We take these statements as a primary method of identifying articles reporting on research that produced the kind of data deposited in public repositories. (1) and (2) show examples of such statements, with varying degrees of specificity. In (1) both the data and location are referred to in a highly specific manner [i.e. ‘the sequence of labA’ and ‘DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL databases (accession no AB281186)’], whereas in (2) data and deposition location are both very general (‘the microarray data’ and ‘MIAMExpress’). While the mention of data, public repositories and accession numbers are strong indicators of deposition statements, (3) and (4) show that these elements can also occur when authors refer to previous work. In the remainder of this article, we will refer to statements that do not report the deposition of data in public repositories—such as (3) and (4) as ‘non-deposition statements’.

The sequence of labA has been deposited in the DDBJ/GenBank/ EMBL databases (accession no AB281186) (PMID 17210789).

The microarray data were submitted to MIAMExpress at the EMBL-EBI (PMID 18535205).

Histone TAG Arrays are a repurposing of a microarray design originally created to represent the TAG sequences in the Yeast Knockout collection (Yuan et al., 2005; NCBI GEO Accession Number GPL1444) (PMID 18805098).

Therefore, the primary sequence of native Acinetobacter CMO is identical to the gene sequence for chnB deposited under accession number AB006902 (PMID 11352635).

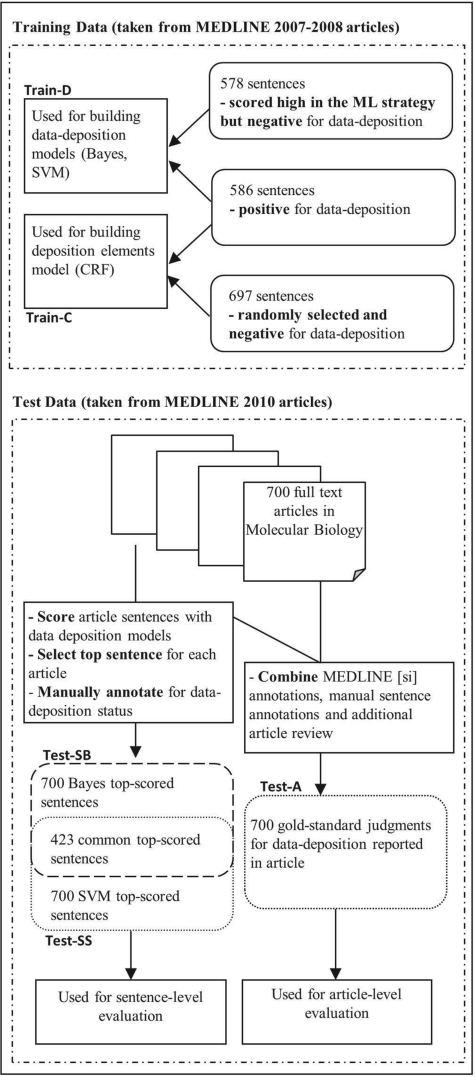

Figure 1 gives an overview of the annotated datasets used in the training and test phases of this work. The various datasets shown on Figure 1 are provided as Supplementary Material and are also freely available to the research community from the NLM/NCBI website. The following sections describe details of the datasets and experiments. In Section 2.1, we describe the method used to collect the training datasets, and the analysis of deposition sentences that we carried out in order to gain an understanding of the variety and common characteristics of these statements. In Sections 2.2 and 2.3, we explain how the training datasets were used to automatically identify deposition elements and perform sentence classification. Finally, in Section 2.4 we present the test set and in Section 2.5 we describe the experiments performed on the test set.

Fig. 1.

Overview of annotated datasets used in this work.

2.1 Training corpus collection and analysis

Corpus collection: to gain a better understanding of the variety of deposition statements across data types, journals and databases, we compiled a corpus of deposition statements based on previous work by Piwowar and Chapman (2008a) and Ochsner et al. (2008) that we extended.

Specifically, 112 microarray deposition statements from 105 articles were obtained using the existing corpora. After a manual review of these statements, two strategies were devised to collect additional statements. Our regular expression strategy consisted in two steps. First, the Ochsner et al. query1 was used to retrieve 2008 articles in PubMed Central. Second, articles were segmented into sentences and sentences likely to report data deposition were retrieved if they met the three following criteria: (i) sentence length was between 50 and 500 characters to avoid section titles and sentence segmentation errors; (ii) sentence contained a mention of GEO or ArrayExpress, which are the largest databases for microarray data (Stokes et al., 2008) or a mention of a GEO or ArrayExpress accession number or the pattern [micro]?array … data| experiment/analys| analyz; and (iii) sentence contained one deposition action seed from the following: deposit, found, submit, submission, available, access, uploaded, entered, posted, provided, assigned, archived.

After manual review, 133 of the 243 candidate sentences were added to the pool of deposition statements. The remaining 110 sentences [such as (3) and (4)] were kept as examples of non-deposition statements, and used in our machine learning strategy to retrieve deposition statements for data other than microarray.

In the machine-learning strategy, we aimed at enriching our training corpus, as proposed by Yeganova et al. (2011). A simple (i.e. only using sentence tokens as features) Naïve Bayes (NB) model was built using the 243 microarray data deposition statements as positive examples and ~ 33 000 sentences (the 110 above non-deposition statements, plus sentences from MEDLINE abstracts that contained the word ‘deposit’ or ‘deposited’) used as negative examples.

In spite of our blanket assumption that the sentences extracted from MEDLINE abstracts were non-deposition statements, we did expect a small number of them to be actual deposition statements. Our reasoning was that the proportion of true non-deposition statements would be high enough to train an efficient model; while applying the model on the set of so-called negatives, it would rank the deposition statements high enough to collect them and adjust our training sets. By iterating on this method recursively, we finally obtained a training set of 586 positive or deposition statements (including the initial 243 microarray deposition statements) and 578 negative or non-deposition statements that scored high with the model (including the initial 110 non-deposition statements). This set was used as training data for building NB and SVM data deposition models, and will be referred to as Train-D (Fig. 1).

Analysis of deposition elements: to better characterize deposition statements, sentences were tagged for components referring to data, deposition action and deposition location using the following guidelines:

‘Data’: a phrase referring to biological data that can be found in public repositories. Patient data and data relevant to ClinicalTrials.gov were not considered. However, generic references to data were marked, when used in the context of biological data. This included expressions such as ‘the data’, ‘the protein’, ‘RNA’, ‘DNA’. In addition, specific references to data such as ‘p53 conditional knockout mouse aCGH data’ were also marked.

‘Action’: a phrase describing the action undertaken by authors regarding depositing data. This includes phrases such as: deposit, submit, upload/download, is available, can be found, etc.

‘General Location’: reference to the location of data deposition, e.g. public repository name or website URL (e.g. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). This also includes a reference to an organization hosting a public repository in the context of data deposition.

‘Detailed Location’: detailed reference to the location of data deposition. This includes accession numbers and specific URLs allowing direct access to the data deposited (e.g. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/GQ386843).

(1t-4t) show how the statements exemplified in (1–4) were tagged.

(1t) <data>The sequence of labA</data> <action>has been deposited </action> <location = “general”> in the DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL databases </location>(<location = "detail">accession no AB281186 </location>).

(2t) <data>The microarray data</data> <action>were submitted</action> <location = “general”> to MIAMExpress at the EMBL-EBI </location>

(3t) <data>Histone TAG Arrays</data> are a repurposing of a microarray design originally created to represent <data>the TAG sequences</data> in the Yeast Knockout collection (Yuan et al., 2005 <location = “general”>NCBI GEO</location> <location = “detail”>Accession Number GPL1444</location>)

(4t) Therefore, <data>the primary sequence of native Acinetobacter CMO</data> is identical to <data>the gene sequence for chnB</data> <action>deposited</action> <location = “detail”>under accession number AB006902</location>

Based on this tagging effort, Table 1 shows a summary of component occurrences over the corpus of 586 deposition statements. Only 16% of sentences contain information that is not included in one of the four tags (7% for full-text sentences, 24% for abstract sentences).

Table 1.

Overview of component occurrences in data deposition statements

| Component | Unique occurrences | Total occurrences | Variability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data | 468 | 645 | 73 |

| Action | 77 | 611 | 13 |

| Location (general) | 387 | 584 | 66 |

| Location (detailed) | 521a | 534 | 98 |

aWhen accession numbers were unified, the variability lessened considerably with 71 unique occurrences only.

‘Data’ is a category with high variability. While general references to data such as ‘the data reported in this paper’ (25 occurrences), ‘the microarray data’ (22 occurrences) and ‘the sequences’ (20 occurrences) are the most frequent phrases used, they are not prevalent overall.

‘Action’ is the category with the least variability. It is expressed by verbs in most cases. In other (rare) cases, nominalization expresses the action, e.g. ‘the deposition/accession number is …’. In more than two-thirds of cases, the action is expressed using a passive verb form, or a present verb + adjective, which is a similar construct. Future tense was used only once in the corpus. (Note that the variability on ‘actions’ is slightly skewed due to the selection of MEDLINE abstract sentences with the words ‘deposit’ or ‘deposition’—variability for actions is otherwise ~20%.)

‘General Location’ is also of high variability, in spite of the fact that there are a limited number of locations referenced, such as GenBank or GEO. Variation factors are as follows: (i) preposition introducing the location at/from/in/into/through/to/on/via/with/within; (ii) URL used (e.g. ~5 variants for GEO); (iii) use of full name and/or abbreviation for institutes (NCBI, EBI) and database (GEO); (iv) typos, spelling errors and other variation (e.g. database versus data bank). ‘Detailed Location’ is a category with relatively low variability if we consider accession numbers as one token type. Variation factors are as follows: (i) preposition introducing the location through/under/with; (ii) reference to ‘accession number’: code/number/no/(super)series; and (iii) list of numbers versus only one number. In the case of a list, a specific data description may be embedded within the list.

2.2 Automatic identification of deposition components in sentences

Based on the analysis above, the identification of the four deposition components defined (data, deposition action, general location and specific location) in deposition statements appeared to be important for extracting specific deposition information. To provide a complete description of the sentences, any part not covered by the four tags was considered as belonging to a fifth default tag, ‘nil’. In addition, we anticipated that these components might be useful features for the classification of deposition statements. For this reason, in addition to the 586 data deposition statements tagged, another 697 non-deposition statements were also tagged manually. The negative sentences tagged here are different from the 578 negative sentences used to train the SVM classifier in order to provide a good balance of sentences that were partly or entirely covered with the ‘nil’ tag. These tagged sentences were then used as a training set (that we will call Train-C) for training a conditional random fields (CRFs) model using MALLET.2

2.3 Automatic identification of deposition sentences

Using the final sets of 586 positive and 578 negative sentences obtained as described in the previous section (Train-D), we built several machine learning models in order to assess the contribution of the following features to the automatic identification of data deposition statements:

Tokens from the sentences (also used in our simple model above)

Sentence relative position in article or abstract

Part-of-Speech (POS) tags obtained with MEDPOST (Smith et al., 2004)

Component tags obtained with CRF model (trained using Train-C)

We compared NB and SVM models built using these features. Table 2 presents the performance (in terms of average precision) of each machine learning method and feature set using 5-fold cross-validation.

Table 2.

Average precision of SVM and NB models for 5-fold cross-validation with various feature sets

| Token | Position tags | POS tags | Component | SVM | NB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-feature set | X | 95.68 | 94.95 | |||

| Two-feature sets | X | X | 95.91 | 94.96 | ||

| Two-feature sets | X | X | 97.33 | 96.11 | ||

| Two-feature sets | X | X | 97.02 | 96.75 | ||

| Three-feature sets | X | X | X | 97.40 | 96.11 | |

| Three-feature sets | X | X | X | 97.04 | 96.75 | |

| Three-feature sets | X | X | X | 97.98 | 97.23 | |

| All four-feature sets | X | X | X | X | 98.06 | 97.23 |

The best performance is shown in bold characters.

2.4 Test corpus

We built a test corpus relying on MEDLINE curation of accession numbers. Specifically, we used the following query to retrieve full-text articles indexed with accession numbers and published in 2010 (we selected 2010 as a publication date to avoid any overlap with our training data):

– (GenBank[si] OR GEO[si] OR PDB[si] OR OMIM[si] OR RefSeq[si] OR PubChem-Substance[si] OR GDB[si]) AND pubmed pmc local[sb] AND 2010[dp] (N = 2,029)

These articles were considered as ‘positive’ for data deposition and were therefore expected to contain a data deposition statement.

Based on the use of the MeSH term Molecular Sequence Data for indexing articles containing references to various types of biological data (as per Chapter 28 of the NLM indexer manual http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/indman/chapter_28.html), we used the following query to retrieve full-text articles containing reference to biological data but no deposition information referenced in MEDLINE:

– Molecular Sequence Data [mh] NOT (GenBank[si] OR GEO[si] OR PDB[si] OR OMIM[si] OR RefSeq[si] OR PubChem-Substance[si] OR GDB[si]) AND pubmed pmc local[sb] AND 2010 [dp] (N=4,708)

These articles were considered as ‘negative’ for data and were therefore not expected to contain data deposition statements.

All articles (N=6737) were downloaded from PubMed Central in xml format and converted to text format for processing. A subset of the corpus comprising 700 articles (including 210 articles from the positive set and 490 articles from the negative set reflecting real-data balance) was selected for testing. The MEDLINE [si] field for the 210 articles selected contained annotations for GenBank (110 articles), PDB (50 articles), GEO (47 articles), RefSeq (4 articles) and GDB (1 article).3

Sentence-level gold standard: the 700 articles were segmented into sentences that were scored both with the NB and SVM classifiers. In order to avoid favoring one particular method, for each method, the top-scored sentence was selected for each article, forming two sets of 700 sentences that were manually annotated to determine whether they were data deposition statements. The set composed of sentences that were top-ranked according to the SVM model was called Test-SS. The set composed of sentences that were top-ranked according to the NB model was called Test-SB. Out of the two sets of 700 sentences, 423 sentences were selected by both methods, so that the manual annotation was performed on one whole set of 700 sentences, and completed by annotating the remaining 277 sentences. The three annotators involved in this task (the authors) were not shown the scores assigned to the sentences by either classifier, and they did not know whether a given sentence came from an article in the positive or negative set. All three annotators first assessed a common set of 100 sentences (30 from the positive article set and 70 from the negative article set to preserve balance) in order to check the inter-annotator agreement and allow some discussion of potentially ambiguous sentences. The remaining 600 sentences for this set were divided evenly between the annotators in three subsets that preserved the overall data balance. Finally, the 277 diverging sentences from the other set were also processed by one annotator.

Article-level gold standard: the 210 articles with an accession number reported in MEDLINE were considered as positive for data deposition in our gold standard. In addition, based on the manual annotation of sentences carried out for building the two sentence-level test sets, articles corresponding to a sentence annotated as positive for data deposition were also considered as positive in the article-level gold standard. This allowed us to add to the gold standard 70 articles reporting the deposition of data in repositories that are not currently covered by MEDLINE curation, such as EMBL/EBI databases. The remaining 420 articles were considered as negative for data deposition in our gold standard. The dataset comprising gold standard judgments on these 700 articles is now referred to as Test-A.

2.5 Sentence and article classification

Classification was performed based on the scoring of article sentences. At the sentence level, a classification decision was made by comparison of the score assigned to the sentence with a threshold, set at the 25th percentile score for positive sentences in the training set: if the score was above the threshold, the sentence was classified as positive for data deposition. Otherwise, the sentence was classified as negative. At the article level, a classification decision was made based on the top-scored sentence. If the top-scored sentence was classified as positive for data deposition, so was the article.

The performance of sentence classification was assessed using accuracy to allow for indicative comparison with inter-annotator agreement. Specifically, accuracy was computed as the number of sentences that were correctly classified as positive or negative according to our gold standard over the total number of sentences in the test set (N=700). We also computed precision, recall and F-measure to allow for a direct comparison with article classification. The performance of article classification was assessed using precision, recall and F-measure based on positive sentences only, to allow for indicative comparison with related work. Specifically, precision was computed as the number of articles that were positive in our gold standard and also classified as positive by the algorithm over the total number of articles classified as positive. Recall was computed as the number of articles that were positive in our gold standard and also classified as positive by the algorithm over the total number of positive articles in the gold standard. F-measure was then computed as the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sentence-level classification

Table 3 shows the performance of selected NB and SVM models for sentence classification on the two sentence test sets (the NB models were applied to Test-SB while the SVM models were applied to Test-SS). While differences between the models were very small for cross-validation on the training set, some of them are emphasized on the test set, in particular between the different feature sets. The best overall performance obtained was 80% F-measure—which corresponds to 87% accuracy. This accuracy compares favorably to the inter-annotator agreement computed on a subset of 100 sentences that was found to be 95%. The classification results from the best model comprised 39 sentences misclassified as negative and 56 sentences misclassified as positive.

Table 3.

Overall precision (P), recall (R), F-measure (F) and accuracy (A) of NB and SVM models for sentence classification

| Model | Features | P | R | F | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | Tokens, position, POS tags | 60 | 84 | 70 | 75 |

| Above features plus component tags | 81 | 78 | 79 | 86 | |

| SVM | Tokens, position, POS tags | 74 | 81 | 77 | 84 |

| Above features plus component tags | 78 | 83 | 80 | 87 |

Threshold is set at the 25th percentile of model scores on the training set Train-D. The best performance is shown in bold characters.

We performed an error analysis in order to assess the underlying cause of these errors, and manually reviewed all misclassified sentences. We found that error causes and distribution was similar for NB and SVM. The breakdown of errors by cause (for SVM) is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Error analysis for SVM sentence classification

| Classification error | Error type | Cases |

|---|---|---|

| False negative | Low score | 34 |

| GS dispute | 2 | |

| Ambiguous sentence | 3 | |

| Total | 39 | |

| False positive | Data reuse | 32 |

| Database mention | 7 | |

| Ambiguous sentence | 7 | |

| GS dispute | 6 | |

| Non biological data | 4 | |

| Total | 56 |

The major sources of error are top sentences that score low in spite of being deposition sentences and sentences that report data reuse and not data deposition. The error analysis also brought to attention eight sentences (marked as ‘GS dispute’ in Table 4) that proved difficult to judge and/or were examples of genuine errors in the gold standard. These problematic sentences seem to be within the limits of 95% annotation consistency determined on the 100 sentences set.

3.2 Article-level classification

Table 5 shows the performance of NB and SVM models for article classification on the test set (both models were applied to Test-A, based on their respective results obtained from Test-SB for NB and Test-SS for SVM). As could be expected, the best results are obtained with the models including component tags as features, which also perform best for sentence classification.

Table 5.

Positive precision (P), recall (R) and F-measure (F) of SVM models for article classification on test set

| Model | Features | P | R | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | Tokens, position, POS tags | 67 | 82 | 74 |

| Above features plus component tags | 83 | 78 | 81 | |

| SVM | Tokens, position, POS tags | 82 | 75 | 79 |

| Above features plus component tags | 86 | 76 | 81 |

Threshold is set at the 25th percentile of model scores on the training set Train-D. The best performance is shown in bold characters.

The classification results from the best NB model comprised 61 articles misclassified as negative and 44 articles misclassified as positive. For this part of the study, we focused the error analysis on positive articles that were classified as negative by our system, in order to assess the underlying cause of the errors. Each case was manually reviewed. The breakdown by cause is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Error analysis for article classification with NB model

| Error type | Cases |

|---|---|

| Low score | |

| Ranked in top 5 | 49 |

| Ranked in top 10 | 2 |

| Other rank | 2 |

| No deposition sentence found in article | 6 |

| Sentence not scored (length >500) | 2 |

| Total | 61 |

The major cause for article misclassification is a direct result of a sentence classification error: the relevant deposition sentence was assigned a score below the threshold. Nonetheless, in these cases relevant sentences appear in the top five scored sentences in 49 out of 53 low scoring cases. Another interesting result from the error analysis is the fact that six articles did not contain a deposition sentence in the full text, and therefore could not be classified properly by our system.

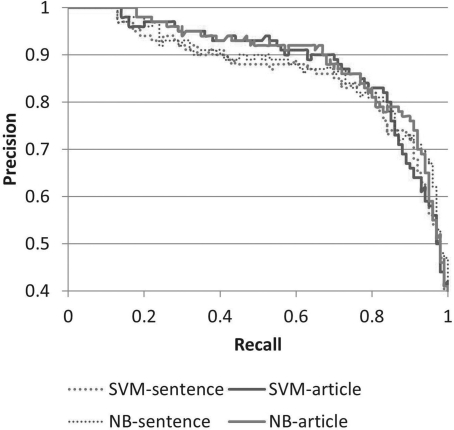

Figure 2 presents a more specific comparison between NB and SVM models built using all feature types. This figure also allows a comparison between sentence-level and article-level classifiers. It can be seen that the overall performance on sentence-level classification and article-level classification is similar.

Fig. 2.

Precision/recall curves for SVM and NB models built using all features.

Nonetheless, sentence-level performance is slightly lower than article performance. This is explained by cases where the gold standard judgments differ at the sentence and article level. In some cases, the top-scored sentence that was assessed at the sentence level is an ambiguous sentence that may have been classified as negative for data deposition because of the lack of additional context. In some cases, the top-scored sentence is truly negative for data deposition, but the article contains another sentence that is positive for data deposition.

3.3 Overall estimation of data deposition statement prevalence in the biomedical literature

To estimate the prevalence of data deposition statements in the biomedical literature, we processed all the PubMed Central articles available to us in full-text XML as of 2 June 2011 (N=827 762) and used the NB model (with component tags as features) to classify them according to data deposition status. In total, ~6.4% of articles (N=52 932) were found to contain a data deposition statement according to our method. For the subset of articles that are part of the MEDLINE database (N=774 442), we also processed abstracts with our method and found that <0.1% contained a data deposition sentence. About 4.2% of the PubMed Central articles included in MEDLINE (N=32 651) had a curated [si] field. Most of these PubMed Central articles were also classified as positive for data deposition by our method (N=22 428). This is consistent with the results of our evaluation.

4 DISCUSSION

Choice of features: interestingly, the difference in performance with and without component tags observed in the cross-validation was greatly magnified on the test sets both for sentence-level and article-level classification. We think this is due to the more challenging nature of the test data. In previous work (e.g. Kim et al., 2011) on MEDLINE abstract sentence classification, structure information has proved to be a useful feature when it is available. Our position feature was intended to serve as a substitute for structure information, but had little impact. Structure information could be considered for future improvement of the sentence classifier; however, this information is not trivial to extract from abstracts (McKnight and Srinivasan, 2003; Ripple et al., 2011); similar issues with added complexity can be anticipated for full text.

Portability of the method: although trained mainly on microarray data deposition statements, the method adapts well to the identification of statements reporting on the deposition of other data such as gene sequences or protein coordinates. This is evidenced by the database breakdown of articles in our test corpus according to the MEDLINE [si] field: 110 articles reported data deposition in GenBank, 50 in PDB and only 47 in GEO.

Comparison to other work: while similar to other work mentioned in the related work section, our approach is not directly comparable to any of the previous studies on data deposition. At the article level, we perform an automatic classification of articles containing data deposition statements, in contrast with Ochsner et al. who performed a one-time manual classification in order to assess the rate of data deposition in 2008. Piwowar et al. assessed machine learning and rule-based algorithms for article classification. However, their approach focused on five databases and relied on the identification of predetermined database names in the full text of articles. In contrast, our approach is generic and aiming at the automatic identification of any biological data deposition in any public repository. Nonetheless, as an indicative comparison, it can be noted that our overall performance for article-level classification is 81% F-measure, compared with overall 69% for Piwowar et al. (on a different evaluation corpus).

Furthermore, in addition to article classification, our approach also retrieves specific data deposition elements allowing for a finer-grained characterization of both data and deposition location. At the statement level, this is also different from the classification of databank accession number sentences performed by Kim et al. (2010) in two ways: first, we are only interested in retrieving sentences containing accession numbers if these sentences are deposition statements (versus comment on the data, or data re-use) and second, we are also interested in retrieving data deposition statements that do not contain accession numbers.

Interest of this study: one general interest of this study is our application of the method proposed by Yeganova et al. in order to build a training corpus when large amounts of unlabeled data are available. We showed that the method of Yeganova et al. could be easily and successfully adapted to our specific classification scenario. More specific to data deposition statement classification, the method presented in this article can be used as a curation aid in MEDLINE or other databases indexing articles with accession numbers; this tool can also be used to help updating current databases. For instance, as announced in York (2006) GEO accession numbers have only been indexed in the [si] field of MEDLINE citations from March 2006 onward. The application of our tool to articles published prior to 2006 could help complete MEDLINE citations with relevant GEO accession numbers. In future work, we are planning to conduct such large-scale studies in order to identify the growth of data production and data deposition in recent years.

Limitations of the study: our study addressed the identification of data deposition statements in full-text articles. While the availability of full-text is definitely a limitation, our overall study of the prevalence of data deposition statements (Section 3.3) indicates that data deposition statements are significantly more often found in the full-text of articles, compared with abstract text. While our method is not limited to data deposition in databases specifically curated in MEDLINE, it is focused on the deposition of biological data as opposed to clinical data as might be recorded in ClinicalTrials.gov, one of the [si] curated databases. Finally, our classification results are obtained based on a threshold of sentence score, which was empirically established at the 25th percentile of model scores on the training data. Other methods of determining the threshold could be investigated in future wok.

5 CONCLUSION

We presented a method to automatically identify biological data deposition statements in biomedical text. The method, an SVM (or, equivalently, NB) classifier using CRF-determined features characterizing data deposition components, was able to correctly identify articles containing data deposition statements with 81% F-measure. Our analysis shows that deposition statements are scored high for all types of databases and biological data types, even those not currently curated in MEDLINE. This shows the potential impact of our method for literature curation. In addition, we believe it provides a robust tool for future work assessing the need for storage space of incoming data in public repositories.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr Won Kim for his assistance in implementing the NB and SVM classification tools.

Funding: Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine. Grant number LM000002-01.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Footnotes

1(microarray[All Fields] OR genome-wide[All Fields] OR microarrays[All Fields] OR ‘expression profile’[All Fields] OR ‘expression profiles’[All Fields] OR ‘transcription profiling’[All Fields] OR ‘transcriptional profiling’[All Fields]) AND (Endocrinology[jour] OR Mol Endocrinol[jour] OR J Biol Chem[jour] OR Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A[jour] OR Mol Cell Biol[jour] OR Nature[jour] OR Nat Med[jour] OR Nat Cell Biol[jour] OR Nat Genet[jour] OR Nat Struct Mol Biol[jour] OR Science[jour] OR Cancer Res[jour] OR FASEB J[jour] OR Cell[jour] OR Nat Methods[jour] OR Mol Cell[jour] OR J Immunol[jour] OR Immunity[jour] OR EMBO J[jour] OR Blood[jour]).

2McCallum, A. K. (2002) ‘MALLET: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit.’ http://mallet.cs.umass.edu.

3One article could be annotated with accession numbers from more than one database.

REFERENCES

- Anonymous Thou shalt share your data. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:209. [Google Scholar]

- Demner-Fushman D., et al. Automatically identifying health outcome information in MEDLINE records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006;13:52–60. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeussler M., et al. Annotating genes and genomes with DNA sequences extracted from biomedical articles. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:980–986. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., et al. IS&T/SPIE's 22nd Annual Symposium on Electronic Imaging. San Jose, CA: 2010. Naïve Bayes and SVM classifiers for classifying databank accession number sentences from online biomedical articles. 7534:75340U-1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.N., et al. Automatic classification of sentences to support Evidence Based Medicine. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl. 2):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S2-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krallinger M., et al. Overview of the protein-protein interaction annotation extraction task of BioCreative II. Genome Biol. 2008;9(Suppl. 2):S4. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-s2-s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight L., Srinivasan P. Categorization of sentence types in medical abstracts. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2003;2008:440–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerchen F., et al. Emerging trend prediction in biomedical literature. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2008:485–489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner S.A., et al. Much room for improvement in deposition rates of expression microarray datasets. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:991. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1208-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar H.A., et al. Sharing detailed research data is associated with increased citation rate. PLoS One. 2007;2:e308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar H.A., Chapman W.W. Proceedings of the BioLINK workshop at ISBM. Toronto, Canada: 2008a. Linking database submissions to primary citations with PubMed Central. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar H.A., Chapman W.W. Identifying data sharing in biomedical literature. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2008b;2008:596–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar H.A., Chapman W.W. Public sharing of research datasets: a pilot study of associations. J. Informetr. 2010;4:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polajnar T., et al. Protein interaction sentence detection using multiple semantic kernels. J. Biomed. Semantics. 2011;2:1. doi: 10.1186/2041-1480-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripple A.M., et al. A retrospective cohort study of structured abstracts in MEDLINE, 1992–2006. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2011;99:160–163. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.99.2.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani F. Machine learning in automated text categorization. ACM Comput. Surv. 2002;1:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L., et al. MedPost: a part-of-speech tagger for bioMedical text. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2320–2321. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes T.H., et al. ArrayWiki: an enabling technology for sharing public microarray data repositories and meta-analyses. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl. 6):S18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S6-S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeganova L., et al. Text mining techniques for leveraging positively labeled data. Proceedings of the ACL Workshop BioNLP. 2011:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Yorks M. GEO accession numbers in MEDLINE®. NLM Tech. Bull. 2006;349:e5. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.