Abstract

Consistent individual differences in behaviour are widespread in animals, but the proximate mechanisms driving these differences remain largely unresolved. Parasitism and immune challenges are hypothesized to shape the expression of animal personality traits, but few studies have examined the influence of neonatal immune status on the development of adult personality. We examined how non-pathogenic immune challenges, administered at different stages of development, affected two common measures of personality, activity and exploratory behaviour, as well as colour-dependent novel object exploration in adult male mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). We found that individuals that were immune-challenged during the middle (immediately following the completion of somatic growth) and late (during the acquisition of nuptial plumage) stages of development were more active in novel environments as adults relative to developmentally unchallenged birds or those challenged at an earlier developmental time point. Additionally, individuals challenged during the middle stage of development preferred orange and avoided red objects more than those that were not immune-challenged during development. Our results demonstrate that, in accordance with our predictions, early-life immune system perturbations alter the expression of personality traits later in life, emphasizing the role that developmental plasticity plays in shaping adult personality, and lending support to recent theoretical models that suggest that parasite pressure may play an important role in animal personality development.

Keywords: activity, Anas platyrhynchos, developmental plasticity, exploratory behaviour, immune function, personality

1. Introduction

Individual animals show consistent differences in behaviour that are maintained both over time and across contexts (reviewed in [1–5]). Such traits are referred to as an individual's temperament or personality [2,5], and have been shown to have a genetic basis [6–8] and be under natural [9–11] and sexual [12,13] selection. Recently, evolutionary and behavioural ecologists have begun to investigate the mechanisms underlying personality differences among individuals. For example, temporal and spatial variation in the environment results in fluctuating selection pressures, thus maintaining genetic variation in personalities (e.g. [14,15]). Another possibility, which remains relatively unexplored, is that perinatal and neonatal environmental factors may shape adult personality [16,17]. Specifically, conditions during ontogeny may alter the development of behaviours, resulting in personality traits that maximize an individual's fitness with respect to a similar (i.e. continued or predicted) future environment.

Phenotypic plasticity can be driven by early-life conditions, and individuals that experience adverse neonatal conditions may have lower-quality territories [18], reduced ornamentation [19], impaired learning and memory [20], and decreased immune function [21] as adults. While it has previously been established that parasites can evoke immediate changes in host behaviour [22–24], early-life challenges resulting from parasite exposure, or immune challenges in general, may also influence the development, formation and evolution of personality traits [25,26]. Thus, the behavioural effects of immune challenges may not be simply transient (i.e. sickness behaviours that cease post-disease recovery), but may instead lead to long-lasting behavioural effects, especially if challenges occur during early, sensitive periods of life. In rodents, recent studies have demonstrated the importance of neonatal immune challenges in shaping adult brain structure [27], immune response [28] and exploratory behaviour [29]. However, questions remain regarding the importance of the timing (i.e. developmental stage) and intensity of infection in shaping adult personality, especially in non-rodent species.

Because mounting an immune response to parasite or pathogen exposure can be energetically costly [30–32], and an individual's personality is linked to food acquisition [33], it is possible that resource-accruing personality traits are related to an individual's past or current immune status [25]. However, experimental tests of this idea are extremely limited. To evaluate the hypothesis that adult personality traits are sensitive to immune status during development [29], we issued an immune challenge (i.e. experimentally induced antibody production) during multiple developmental stages (early, middle and late) to mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos), a precocial species that is easy to rear in captivity (thus minimizing maternal effects), and quantified variation in adult personality. In both novel and familiar environments, we quantified activity and exploratory behaviour, both of which are personality traits that have been identified in a variety of taxa including arthropods (Acheta domesticus [34]), fish (Gasterosteus aculeatus [35]), birds (Parus major [7]) and mammals (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus [36]). Because work in rodents has shown that immune challenges during development increase exploratory behaviours later in life [29], and because selection may favour individuals that are more active when exposed to pathogens (and thus more likely to leave a pathogen-rich site [26]), we predicted that developmentally immune-challenged individuals would show increased activity and exploratory behaviour as adults relative to control, developmentally unchallenged individuals. Furthermore, because perturbations earlier in life can have stronger effects on adult phenotype than those occurring later in life [37], we predicted that exploration and activity levels would be highest in individuals that were immunologically challenged earlier in development. We also measured colour-specific object exploration by examining responses of ducks to novel objects of varying colours (i.e. red, orange, green and white). Coloration can be an indicator of nutritious food items [38], toxic or chemically defended food (i.e. aposematism [39]), or valuable courtship objects (e.g. bower decorations used by bowerbirds, Ptilonorhynchus violaceus [40]). Anecdotal evidence in mallards suggests generalized preferences for green and avoidance of red and orange objects [41], but also that individuals can differ substantially in their colour preferences [42]. Wariness of aposematic (e.g. red or orange) prey has been shown to be negatively correlated with exploratory behaviour in great tits (Parus major) [43]; therefore, we predicted that immune-challenged birds, in addition to being more exploratory, would also be more likely to approach traditionally avoided colours (e.g. red and orange) than control birds.

2. Methods

(a). Origin and maintenance of birds

We acquired 44 one-day-old male mallard ducklings from a commercial breeder (Metzer Farms, Gonzales, CA, USA) during December 2008. For the first 45 days of life, birds were reared indoors in wire cages (60 × 60 × 60 cm) and maintained at approximately 30°C under a 13 L : 11 D cycle. Individuals were housed in randomly assigned groups of four until they were 20 days old, in groups of three from 20 to 23 days of age, and in groups of two from 23 to 45 days old; this was done to mimic typical brood sizes and to avoid stress associated with individual housing of ducklings (M. W. Butler 2007, personal observation). At day 45, all birds were moved outside and housed individually (in the same wire cages) to ensure typical plumage development [44]. From arrival until individuals were 52 days old, infrared heat lamps were placed outside of each cage to create a constant 30°C environment, and photoperiod followed the natural light–dark cycle (approximately 10.5 L : 13.5 D at 45 days old to 13.75 L : 10.25 D at 21 weeks old). In all instances, cedar wood chips were provided as bedding, and food (Waterfowl Starter for the first 7 weeks, and Waterfowl Maintenance thereafter; Mazuri, Richmond, IN, USA) and tap water were provided ad libitum throughout the study.

(b). Developmental manipulation and sample collection

Ducklings were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups—EARLY, MIDDLE and LATE—or a control group (n = 11 for each), and cage mates were not assigned to the same treatment. Individuals in the EARLY group received immune challenges during the period of maximum somatic growth (at 3–5 weeks of age [45]), MIDDLE individuals received immune challenges when somatic growth was complete but prior to the acquisition of nuptial plumage (at 8–10 weeks of age) and LATE individuals received immune challenges when ducks were undergoing molt into their nuptial plumage (at 13–15 weeks of age [44]). Immune challenges consisted of a total of three injections, administered once a week over the three-week treatment period. The first injection consisted of 0.2 ml packed sheep red blood cells (SRBC; Innovative Research, suspended at 10 per cent in saline) emulsified in 0.5 ml Complete Freund's Adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) administered intra-abdominally (sensu [46]). The second and third injections were similarly administered, and consisted of 0.2 ml SRBC suspended in 10 per cent saline emulsified in 0.5 ml of Incomplete Freund's Adjuvant (IFA; Sigma F5506, St Louis, MO, USA). We chose to administer this specific immune challenge because it stimulates both the humoral and innate immune systems, and induces the primary and secondary immune responses of individuals. We did not administer sham treatments to CONTROL individuals (n = 11) due to the likelihood of inadvertently eliciting a small immune response when puncturing the skin during injection (sensu [47]). However, CONTROL birds were handled for a similar amount of time as experimental birds, such that birds experienced similar levels of handling stress in all groups.

At the beginning and end of each treatment period, we measured body mass (to the nearest gram) for all individuals. As part of a separate immunological study, all individuals received a series of injections when they were 18 weeks old: a subcutaneous phytohaemagglutinin injection of 0.2 ml of 1 mg ml−1 PHA (Sigma L8754) suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Fisher BP399) and two intra-abdominal injections of 0.2 ml SRBC mixed with 0.25 ml of 1 mg ml−1 aqueous keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Sigma H7017) emulsified in 0.25 ml of IFA. This stimulation of the immune system at the adult stage may have influenced adult behaviour [48], although we lack the data to assess the extent to which individuals were still producing antibodies during the behavioural trials. Therefore, we interpret the results of our behavioural test as representing a possible interaction of developmental immune history with an adult immune challenge. We recorded mass at the end of this adult immune assessment and used this value in all behavioural analyses presented here; we did this because all behavioural trials were concluded within 10 days of this measurement, and because individual mass at this age is correlated with mass at 13, 14, 15 and 16 weeks of age and throughout the adult immune assessment (all R > 0.7, all p < 0.0001).

(c). Behavioural trials

When individuals were 21 weeks of age (i.e. the age at which males typically begin exhibiting courtship behaviour and are thus considered sexually mature [49]), we conducted two rounds of behavioural trials. Round 1 was conducted in a novel environment (figure 1) containing four objects (see below). Round 2 was conducted in the same environment (i.e. now a familiar environment), but incorporated four different objects (i.e. we selected items that were of novel shape and appearance for each round). In round 1, objects consisted of small flat-bottomed plastic bowls (24 cm diameter × 9 cm height) primed with plastic primer (Rust-Oleum Specialty) and painted one of four different colours: red (Gloss Apple Red, 1966830), green (Gloss Meadow Green, 1934830), orange (Gloss Real Orange, 1953830) or white (Gloss White, 1992830; all paints Rust-Oleum Painter's Touch, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). In round 2, novel objects consisted of small toy ducks (approx. 9 cm long × 7 cm wide × 7 cm high) painted in an identical fashion. In all instances, each novel object was placed at the centre of a chalk circle (approx. 55 cm diameter) drawn on the floor of the arena. These chalk circles allowed observers to objectively define instances of interactions with novel objects, because individuals within that circle were deemed to be close enough to touch the object. All novel objects were placed equidistant (approx. 120 cm) from the point of bird release in the test arena (figure 1), and relative arrangement of the different coloured objects was randomly selected within a treatment, but balanced among treatments.

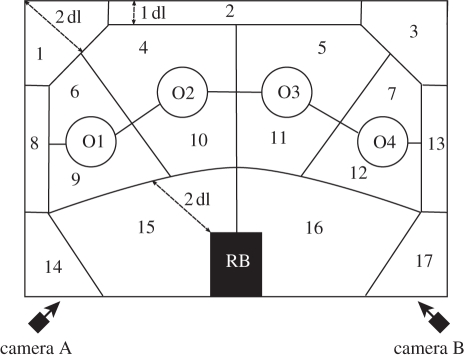

Figure 1.

Overhead schematic view of the test arena. Birds entered the test arena from the release box (RB). The room contained four novel objects placed at the centre of a blue chalk circle (approx. 55 cm diameter) drawn on the floor of the arena (O1–O4). The test arena was divided into an additional 17 sections; divisions between sections were visually estimated by observers during data collection using the relative size of the duck (i.e. distances are approximated in duck lengths; dl, length from beak tip to tail tip).

All trials were run between the hours of 08.30 and 19.00 in one of two indoor rooms (approx. 2.8 m long × 3.4 m wide) that were visually and acoustically isolated from the outdoor enclosures and used typical indoor, incandescent lighting conditions. The behaviour of each bird was filmed with two digital camcorders (ZR830, Canon USA, Inc., Lake Success, NY, USA; Everio, JVC USA Inc., Wayne, NJ, USA), which were mounted to provide a full view of the test arena; sheets of cardboard separated the testing arena from the cameras and associated wires. Prior to each trial, we removed all debris and faecal matter from the floor of the arena to ensure that no faecal cues influenced the behaviour of subsequent individuals. All birds were tested on one day for round 1, and then again 3 days later for round 2. At the beginning of each trial, a single duck was transferred from its home cage to the experimental release box (a rectangular solid wooden frame covered by an opaque cloth) within the test arena (figure 1) and left to acclimate in the dark. After 2 min, the lights were turned on while a remote pulley system was used to simultaneously lift the cloth covering the release box, thus allowing the focal bird to explore the test arena in isolation. Trials lasted 20 min (from the time the lights were turned on) and, at the end of each trial, birds were returned to their home cages. Trials were sequentially alternated among birds from the four immune treatments to avoid time-of-day confounds.

Videos were later analysed by two individuals blind to experimental treatments. Observers recorded all interactions with novel objects and performed instantaneous scan samplings at 20 s intervals to quantify both the location of the focal individual within the arena and whether the individual was active (e.g. flying, running, walking) or inactive (e.g. standing, sitting). We quantified activity level as (i) the total number of transitions (or the number of times an individual was observed in different sections of the test arena between consecutive scans), and (ii) the frequency with which focal birds were recorded as standing or sitting (i.e. inactivity [34]). We defined exploratory behaviour as (i) the total number of approaches to novel objects (defined as the duck being within the chalk circle, regardless of body orientation or travel direction; repeated approaches were counted), (ii) the number of different novel objects visited (each object included only once [50]), and (iii) the total number of unique room sections visited, where sections were defined by dividing the test arena into 22 segments [51,52] (see figure 1). Finally, we also assessed colour-dependent novel object exploration by recording the colour of each novel object approached and calculating the total number of approaches to objects of each colour (i.e. red, orange, white and green).

(d). Statistical analysis

During round 1, one duck exited the test arena (entering the compartment holding the video cameras) and was excluded from statistical analyses for that round. We found no differences between observers in their calculations of the total number of approaches to each coloured novel object, the total number of objects visited, the number of room sections visited, the total number of transitions or the number of inactivity observations for round 1 (all p > 0.27) or round 2 (p > 0.34); thus, we pooled data from the two observers, calculated an average score for each behavioural measure and used that value in all subsequent analyses.

To test for differences in activity level, we performed multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs), with treatment as a fixed factor, time of day and body mass as covariates, and total number of transitions between different room sections and amount of time spent inactive as the dependent variables for each round. To test for differences in exploratory behaviour within novel and familiar environments, we ran MANCOVAs with the same independent variables as described above, and total number of approaches to novel objects, number of different novel objects visited and number of room sections visited as dependent variables for each round. To test whether overall patterns of behaviour were correlated within individuals across rounds, which is a prediction of personality measures [53], we generated residuals for each MANCOVA and calculated Pearson's correlation coefficients between residuals for both rounds (i.e. novel and non-novel contexts) for both exploratory behaviour and activity level.

We used chi-square analysis to test for treatment differences in colour-dependent novel object exploration. If differences were detected as a function of both treatment and colour, we identified where these differences existed by running follow-up chi-square analyses within each colour, and compared 95 per cent confidence intervals (CI) to expected proportions (i.e. the proportion at which CONTROL birds approached objects of that colour). Because these were post hoc chi-square analyses, we Bonferroni-corrected our α to 0.0125 to reflect the fact that we were running four separate follow-up tests. When differences were not detected as a function of both treatment and colour, we pooled treatments and ran a follow-up chi-square analysis to test for differences by colour alone, and compared 95 per cent CI to the null hypothesis (25% for each colour). All statistics were performed in SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC), the residuals from all analyses were normally distributed, and, unless otherwise stated, we used an α level of 0.05 to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

(a). Within-individual patterns of behaviour

All behaviours were correlated within individual mallards across rounds (behaviour as a function of individual: all F43,43 > 1.87, all p < 0.022, R2 > 0.65), with the exception of total number of approaches to novel objects (F43,43 = 1.50, p = 0.094, R2 = 0.60), demonstrating the general behavioural consistency within individuals across contexts. Additionally, residuals from MANCOVAs were significantly correlated within individuals between round 1 and round 2 for activity level (r = 0.43; p = 0.0038) and exploratory behaviour (r = 0.38; p = 0.0118), also indicating behavioural consistency of individuals across contexts, demonstrating that our measures of exploration and activity represent personality traits.

(b). Activity level

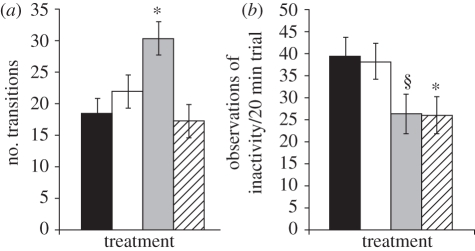

In round 1 (novel environment), activity level differed significantly by developmental immune treatment (Wilks's λ = 0.59, F6,72=3.66, p = 0.0031; figure 2) and time of day (Wilks's λ = 0.72, F2,36 = 6.84, p = 0.0030), but not body mass (Wilks's λ = 0.98, F2,36 = 0.33, p = 0.72). Post hoc contrasts revealed that MIDDLE birds made more transitions (p = 0.036) and tended to be inactive less frequently (p = 0.0596) compared with CONTROL birds, while LATE birds spent significantly less time standing or sitting than CONTROL birds (p = 0.031). In round 2 (familiar environment), however, there was no effect of treatment, time of day or individual mass on activity variables (all Wilks's λ > 0.86, F < 1.54, p > 0.23).

Figure 2.

Differences in activity level in round 1 as a function of developmental immune treatment. (a) Number of transitions between sections; (b) incidence of inactivity. Shown are mean with SEM error bars for CONTROL (black bars), EARLY (open bars), MIDDLE (grey bars) and LATE (hatched bars) birds (see text for definitions of treatment groups). Least-squares mean comparisons revealed that MIDDLE birds made significantly more transitions between room sections in consecutive 20 s scans compared to CONTROL birds, and LATE birds were inactive less frequently than CONTROL birds (*p < 0.05). MIDDLE birds also tended to be inactive less frequently than CONTROL birds (§0.05 < p < 0.06).

(c). Exploratory behaviour

For round 1, exploratory behaviour did not differ by immune treatment (Wilks's λ = 0.81, F9,85.3 = 0.88, p = 0.54) or body mass (Wilks's λ = 0.96, F3,35 = 0.49, p = 0.69), though there was a non-significant trend for exploratory behaviour to increase later in the day (Wilks's λ = 0.82, F3,35 = 2.61, p = 0.067). Similarly, exploratory behaviour in round 2 did not differ by treatment, mass or time of day (all Wilks's λ > 0.74, F < 1.78, p > 0.17).

(d). Colour-dependent novel object exploration

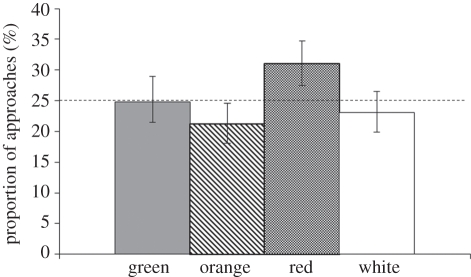

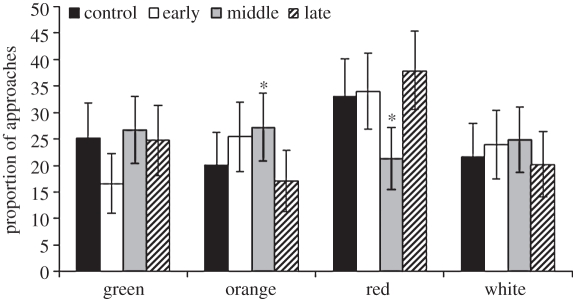

In round 1, the frequency of colours visited did not differ by treatment (χ29 = 14.8, p = 0.096), although the total number of object approaches did differ by colour (χ23 = 13.96, p = 0.0030), with individuals approaching red and avoiding orange objects more often than expected by chance (95% CI did not encompass 25% proportion; figure 3). In contrast, the number of approaches to objects of different colours varied by treatment in round 2 (χ29 = 19.41, p = 0.022). To uncover where these differences existed, within each colour we compared the 95 per cent CI of the approaches of each treatment group to the approaches of CONTROL birds within round 2 (orange, 20.1%; white, 21.6%; green, 25.2%; red, 33.0%), using a Bonferroni-corrected α = 0.0125. Birds in the MIDDLE experimental group significantly differed from CONTROL birds (χ23 = 13.47, p = 0.0037), approaching orange and avoiding red objects more often than CONTROL individuals (figure 4). Approaches by EARLY individuals tended to differ from those by CONTROL birds (χ23 = 7.89, p = 0.0484), with EARLY birds tending to avoid green more than CONTROL birds (figure 4). There were no differences in colour of the objects approached between LATE and CONTROL birds (χ23 = 2.08, p = 0.55; figure 4).

Figure 3.

Colour-dependent novel object exploration in round 1 (novel environment). Irrespective of treatment, birds approached red objects and avoided orange objects more often than expected by chance (95% CI did not encompass 25% proportion for either). Proportions are presented with 95% CI, and horizontal dashed line represents 25% value.

Figure 4.

Colour-dependent novel object exploration of adult mallards during round 2 (familiar environment) as a function of developmental immune treatment and object colour. Proportions are presented with 95% confidence intervals. EARLY birds tended to avoid green more often than CONTROL birds, while MIDDLE birds avoided red and approached orange objects more often than CONTROL individuals (*p<0.05). There was no difference in colour-dependent novel object exploration between LATE and CONTROL birds.

4. Discussion

A wave of recent reviews in the animal personality literature has suggested that more attention be paid to developmental and immunological aspects of behavioural development [16,17,26]. Here, we show that immune challenges (i.e. stimulation of antibody production) administered during development significantly affected personality traits in adult, recently immune-challenged ducks, and that the age at which an individual was challenged differentially affected the expression of these personality traits. Specifically, we found that immune challenges during the MIDDLE and LATE developmental periods increased activity levels of adult male mallards in a novel environment, and that immune challenges during the MIDDLE developmental period affected colour-dependent novel object exploration behaviour, such that MIDDLE birds preferred the orange objects they had traditionally avoided [41].

The evolution of animal personalities may have been favoured as a mechanism for maximizing fitness in the face of pathogen pressure [25,26]. For example, while immune system activation can incur significant fitness costs (e.g. reductions in adult ornamentation [54,55] and survival [30,46]), the extent of such costs may be modulated by personality, driving inter-individual differences in resource acquisition. Consistent with these models of parasite/immune system-mediated personality variation, we found that individuals that were immune-challenged during development expressed behaviours that are consistent with resource-accruing personalities (e.g. greater activity in novel environments for MIDDLE and LATE birds; more tolerant of typically-avoided orange novel objects for MIDDLE birds). These behaviours contrast with traditional sickness behaviours (e.g. inactivity [48]), which are exhibited concurrently with immune response. We found that developmentally immune-challenged birds were more active in novel environments, suggesting that (i) developmental immune challenges can shape adult personality in general, (ii) duration of time between developmental and adult immune challenges can affect adult personality or (iii) developmental immune history interacts with adult immune challenges, reducing the expression of typical sickness behaviours at adulthood. However, because all mallards were challenged as adults three weeks prior to behavioural tests, we currently lack the ability to distinguish between these three possibilities. Additionally, though we did not quantify boldness, we found that MIDDLE birds exhibited shifts in colour-dependent novel object exploration (i.e. individuals appeared to overcome an inherent avoidance of orange objects) that are consistent with boldness or risk-taking behaviour. Recent studies have demonstrated a link between boldness and mate selection (i.e. bolder males establish pair bonds earlier [56]), even when controlling for an individual's coloration [57]. Thus, in our study system, elevated activity levels in a novel environment may influence both resource acquisition and reproductive success (via an increase in the likelihood of mate location and acquisition). Although such behaviours are not without their risks (e.g. increased likelihood of being detected by predators [58]), the elevated activity levels of MIDDLE and LATE male mallards in novel environments may reflect behavioural responses that both compensate for the costs associated with immune system activation and also maximize fitness.

An additional (but not mutually exclusive) hypothesis to explain our results is that immune system activation may induce individuals to disperse to new environments where pathogen pressure is lower [59]. Recent studies have documented personality-dependent dispersal tendencies in some animals; dispersing individuals show differences in activity pattern, boldness and aggressiveness compared with non-dispersing individuals (reviewed in [60]). More specifically, higher activity levels are associated with dispersal tendencies or greater dispersal distances in North American red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus [36]), mole rats (Heterocephalus glaber [61]), and common lizards (Lacerta vivipara [62]). Moreover, immune challenges promote dispersal events in insects [63], and early life parasitism is associated with increased natal dispersal in cliff swallows (Hirundo pyrrhonota [64]). Thus, the greater activity levels in novel environments induced by immune challenges may manifest in nature as greater post-growth dispersal tendencies and distances that reduce the costs of staying in an environment that promotes infection.

Contrary to our predictions, individuals challenged during the earliest part of development did not show the greatest change in adult personality; in fact, these individuals showed similar levels of activity and exploration behaviour to birds in the control group. These results suggest that challenges during the growth period of development may have less of an effect on the development of personality traits than similar challenges later in life. While individuals in all three experimental groups exhibited an immunological response to the treatment (increased constitutive IgG titre, M. W. Butler 2009, unpublished data), EARLY birds, which were in an active growth period during developmental treatment, may have had to allocate a greater proportion of resources to somatic development and, as a consequence of resource trade-offs, fewer resources to neonatal immune response. Although a comprehensive understanding of the neurological basis of personality expression is currently lacking, it is plausible that changes in brain physiology or structure at different stages of development could affect personality. Immune challenges can affect multiple aspects of neural physiology and structure, including neurogenesis [27], synthesis of proinflammatory cytokine [65] or transcription factors [66] in the brain, and modification of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [28]. Alterations to these processes at different developmental stages may have differential effects; thus, differences between birds that were immune-challenged at different ages may be mechanistically linked to age-specific patterns of neural development. However, these processes are not well understood in many species and their relationship to personality development remains to be explored.

We also quantified colour-dependent novel object exploration behaviour and found that, in a novel environment, birds (irrespective of treatment) showed consistent among-individual colour preferences, tending to associate more with red objects (contrary to previous work [41]) and less with orange ones (in accordance with previous work [41]). While we cannot explicitly test the mechanism behind such a red object preference, we suspect that this behaviour may be due at least in part to the fact that their automatic water bowls had red plastic bottoms (the only highly chromatic structure in their cages). Thus, these birds may have habituated to, or even experienced positive reinforcement for, associating with red objects. We had predicted that immune-challenged individuals would be more exploratory, and would therefore approach avoided colours (e.g. orange [41]) more frequently than controls. Indeed, immune challenges during development were associated with changes in the propensity to explore novel objects of a specific colour (i.e. treatment effects absent in round 1 manifested in round 2). Specifically, MIDDLE birds shifted their colour-dependent novel object exploration away from red and towards orange. One possible explanation for this finding is that MIDDLE birds may have been faster to learn that orange items are not costly, although previous work with rats has tied prenatal immune challenges with impairment of both memory [67] and learning [68]. Nonetheless, our findings highlight that behaviours that appear innate (colour-dependent novel object approaches) are not only affected by developmental history, but may also change over time (i.e. there were no differences by treatment in round 1, but there were some in round 2).

In conclusion, we found evidence that at least one adult animal personality trait (activity level) was affected by neonatal immune challenges. Importantly, we demonstrate (for the first time, to our knowledge) that the specific timing of immune challenges during development differentially shapes adult personality expression. These results emphasize the importance of early-life conditions for adult personality traits and suggest that developmental plasticity of personality traits may contribute to the evolution and maintenance of inter-individual differences in behaviour. Furthermore, this study, though centred on non-infectious challenges, supports recent hypotheses positing that parasites and pathogens may generate variation in personality. We suggest that future studies investigating the ecological roles (e.g. resource acquisition, dispersal patterns) and underlying mechanisms (e.g. neural development, nutrient assimilation ability) of developmentally plastic personality traits are necessary to understand the evolutionary origin and maintenance of inter-individual differences in animal personality traits.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank David Anderson, Geoff Kimmel, Melissa Meadows, Kasey Pierson, Christy Ross, Todd Schuster and Elizabeth Tourville for animal and laboratory assistance. Funding was provided to M.W.B. by the American Ornithologists' Union, the Arizona State University Graduate and Professional Student Association (Research Grant and JumpStart Grant), and the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology, to M.B.T. by the National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant (IOS-0923694), and to K.J.M. by the National Science Foundation (IOS-0746364). We would also like to thank L. Martin, J. Grindstaff and two anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved the quality of the manuscript. All procedures were approved under Arizona State University's IACUC, approval number 07-910R. Author contributions: all authors designed the research; M.W.B., M.B.T. and M.R. secured funding; M.W.B. and M.B.T. performed the research; M.W.B. and M.R. analysed samples and data; all authors wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Wilson D. S., Clark A. B., Coleman K., Dearstyne T. 1994. Shyness and boldness in humans and other animals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 442–446 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90134-1 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(94)90134-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gosling S. D. 2001. From mice to men: what can we learn about personality from animal research? Psychol. Bull. 127, 45–86 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.45 (doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.45) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sih A., Bell A., Johnson J. C. 2004. Behavioral syndromes: an ecological and evolutionary overview. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 372–378 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.009 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sih A., Bell A. M., Johnson J. C., Ziemba R. E. 2004. Behavioral syndromes: an integrative overview. Quart. Rev. Biol. 79, 241–277 10.1086/422893 (doi:10.1086/422893) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Réale D., Reader S. M., Sol D., McDougall P. T., Dingemanse N. J. 2007. Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol. Rev. 82, 291–318 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00010.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00010.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koolhass J. M., Korte S. M., De Boer S. F., Van Der Vegt B. J., Van Reenen C. G., Hopster H., De Jong I. C., Ruis M. A. W., Blokhuis H. J. 1999. Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress-physiology. Neurosci. Behav. Rev. 23, 925–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingemanse N. J., Both C., Drent P. J., van Oers K., van Noordwijk A. J. 2002. Repeatability and heritability of exploratory behavior in great tits from the wild. Anim. Behav. 64, 929–938 10.1006/anbe.2002.2006 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.2006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drent P. J., van Oers K., van Noordwijk A. J. 2003. Realized heritability of personalities in the great tit (Parus major). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 45–51 10.1098/rspb.2002.2168 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2168) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Réale D., Festa-Bianchet M. 2003. Predator-induced natural selection on temperament in bighorn ewes. Anim. Behav. 65, 463–470 10.1006/anbe.2003.2100 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2100) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dingemanse N. J., Réale D. 2005. Natural selection and animal personality. Behaviour 142, 1159–1184 10.1163/156853905774539445 (doi:10.1163/156853905774539445) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boon A. K., Réale D., Boutin S. 2007. The interactions between personality, offspring fitness and food abundance in North American red squirrels. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1094–1104 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01106.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01106.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Oers K., Drent P. J., Dingemanse N. J., Kempenaers B. 2008. Personality is associated with extrapair paternity in great tits, Parus major. Anim. Behav. 76, 555–563 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.03.011 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.03.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuett W., Tregenza T., Dall S. R. X. 2010. Sexual selection and animal personality. Biol. Rev. 85, 217–246 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00101.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00101.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dingemanse N. J., Both C., Drent P. J., Tinbergen J. M. 2004. Fitness consequences of avian personalities in a fluctuating environment. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 847–852 10.1098/rspb.2004.2680 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2680) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith B. R., Blumstein D. T. 2008. Fitness consequences of personality: a meta-analysis. Behav. Ecol. 19, 448–455 10.1093/beheco/arm144 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arm144) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Réale D., Dingemanse N. J., Kazem A. J. N., Wright J. 2010. Evolutionary and ecological approaches to the study of personality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 3937–3946 10.1098/rstb.2010.0222 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0222) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamps J. A., Groothuis T. G. G. 2010. Developmental perspectives on personality: implications for ecological and evolutionary studies of individual differences. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 4029–4041 10.1098/rstb.2010.0218 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0218) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haywood S., Perrins C. M. 1992. Is clutch size in birds affected by environmental conditions during growth? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 249, 195–197 10.1098/rspb.1992.0103 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1992.0103) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohlsson T., Smith H. G., Råberg L., Hasselquist D. 2002. Pheasant sexual ornaments reflect nutritional conditions during early growth. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 21–27 10.1098/rspb.2001.1848 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1848) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pravosudov V. V., Lavenex P., Omanska A. 2005. Nutritional deficits during early development affect hippocampal structure and spatial memory later in life. Behav. Neurosci. 119, 1368–1374 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1368 (doi:10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1368) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Block M., Stoks R. 2008. Compensatory growth and oxidative stress in a damselfly. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 781–785 10.1098/rspb.2007.1515 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1515) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen S. B., Gerritsma S., Yusah K. M., Mayntz D., Hywel-Jones N. L., Billen J., Boomsma J. J., Hughes D. P. 2009. The life of a dead ant: the expression of an adaptive extended phenotype. Am. Nat. 174, 424–433 10.1086/603640 (doi:10.1086/603640) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart B. L. 1988. Biological basis of the behavior of sick animals. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 12, 123–137 10.1016/S0149-7634(88)80004-6 (doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(88)80004-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore J. 2002. Parasites and the behavior of animals. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barber I., Dingemanse N. J. 2010. Parasitism and the evolutionary ecology of animal personality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 4077–4088 10.1098/rstb.2010.0182 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0182) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kortet R., Hedrick A. V., Vainikka A. 2010. Parasitism, predation and the evolution of animal personalities. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1449–1458 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01536.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01536.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bland S. T., Beckley J. T., Young S., Tsang V., Watkins L. R., Maier S. F., Bilbo S. D. 2010. Enduring consequences of early-life infection on glial and neural cell genesis within cognitive regions of the brain. Brain Behav. Immun. 24, 329–338 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.012 (doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galic M. A., Spencer S. J., Mouihate A., Pittman Q. J. 2009. Postnatal programming of the innate immune response. Integrat. Comp. Biol. 49, 237–245 10.1093/icb/icp025 (doi:10.1093/icb/icp025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rico J. L. R., Ferraz D. B., Ramalho-Pinto F. J., Morato S. 2010. Neonatal exposure to LPS leads to heightened exploratory activity in adolescent rats. Behav. Brain Res. 215, 102–109 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.07.001 (doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2010.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eraud C., Jacquet A., Faivre B. 2009. Survival cost of an early immune soliciting in nature. Evolution 63, 1036–1043 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00540.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00540.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klasing K. C. 2004. The costs of immunity. Acta Zool. Sinica 50, 961–969 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lochmiller R. L., Deerenberg C. 2000. Trade-offs in evolutionary immunology: just what is the cost of immunity? Oikos 88, 87–98 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880110.x (doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880110.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurvers R. H. J. M., Prins H. H. T., van Wieren S. E., van Oers K., Nolet B. A., Ydenberg R. C. 2010. The effect of personality on social foraging: shy barnacle geese scrounge more. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 601–608 10.1098/rspb.2009.1474 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1474) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson A. D. M., Godin G. J. 2010. Boldness and intermittent locomotion in the bluegill sunfish Lepomis macrochirus. Behav. Ecol. 21, 57–62 10.1093/beheco/arp157 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arp157) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell A. M., Stamps J. A. 2004. Development of behavioural differences between individuals and populations of sticklebacks Gasterosteus aculeatus. Anim. Behav. 68, 1339–1348 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.05.007 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.05.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boon A. K., Réale D., Boutin S. 2008. Personality, habitat use, and their consequences for survival in North American red squirrels Gasterosteus aculeatus. Oikos 117, 1321–1328 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16567.x (doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16567.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindström J. 1999. Early development and fitness in birds and mammals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 343–348 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01639-0 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01639-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaefer H. M., McGraw K. J., Catoni C. 2008. Birds use fruit colour as honest signal of dietary antioxidant rewards. Funct. Ecol. 22, 303–310 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01363.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01363.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skelhorn J., Rowe C. 2010. Birds learn to use distastefulness as a signal of toxicity. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1729–1734 10.1098/rspb.2009.2092 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2092) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borgia G. 2008. Experimental blocking of UV reflectance does not influence use of off-body display elements by satin bowerbirds. Behav. Ecol. 19, 740–746 10.1093/beheco/arn010 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arn010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oppenheim R. W. 1968. Color preferences in the pecking response of newly hatched ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 66, 1–17 10.1037/h0026537 (doi:10.1037/h0026537) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pickens A. L. 1935. Studies in avian color reaction. Condor 37, 279–281 10.2307/1363706 (doi:10.2307/1363706) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Exnerová A., Svádová K. H., Fučíková E., Drent P., Štys P. 2010. Personality matters: individual variation in reactions of naive bird predators to aposematic prey. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 723–728 10.1098/rspb.2009.1673 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butler M. W., McGraw K. J. 2009. Indoor housing during development affects molt, carotenoid circulation, and beak coloration of mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). Avian Biol. Res. 2, 203–211 10.3184/175815509X12570082777157 (doi:10.3184/175815509X12570082777157) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butler M. W., McGraw K. J. 2011. Past or present? Relative contributions of developmental and adult conditions to adult immune function and coloration in mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). J. Comp. Phys. B 181, 551–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanssen S. A., Hasselquist D., Folstad I., Erikstad K. E. 2004. Costs of immunity: immune responsiveness reduces survival in a vertebrate. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 925–930 10.1098/rspb.2004.2678 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adler K. L., Peng P. H., Peng R. T., Klasing K. C. 2001. The kinetics of hemopexin and α1-acid glycoprotein levels induced by injection of inflammatory agents in chickens. Avian Dis. 45, 289–296 10.2307/1592967 (doi:10.2307/1592967) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Owen-Ashley N. T., Wingfield J. C. 2007. Acute phase responses of passerine birds: characterization and seasonal variation. J. Ornithol. 148, S583–S591 10.1007/s10336-007-0197-2 (doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0197-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drilling N., Titman R., Mckinney F. 2002. Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). Birds of North America Online (ed. Poole A.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; See http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/658 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verbeek M. E. M., Drent P. J., Wiepkema P. R. 1994. Consistent individual differences in early exploratory behavior of male great tits. Anim. Behav. 48, 1113–1121 10.1006/anbe.1994.1344 (doi:10.1006/anbe.1994.1344) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones K. A., Godin G. J. 2010. Are fast explorers slow reactors? Linking personality type and anti-predator behavior. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 625–632 10.1098/rspb.2009.1607 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1607) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurvers R. H. J. M., Eijkelenkamp B., van Oers K., van Lith B., van Wieren S. E., Ydenberg R. C., Prins H. H. T. 2009. Personality differences explain leadership in barnacle geese. Anim. Behav. 78, 447–453 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.06.002 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.06.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dingemanse N. J., Kazem A. J. N., Réale D., Wright J. 2010. Behavioural reaction norms: animal personality meets individual plasticity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 81–89 10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.013 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peters A., Delhey K., Denk A. G., Kempenaers B. 2004. Trade-offs between immune investment and sexual signaling in male mallards. Am. Nat. 164, 51–59 10.1086/421302 (doi:10.1086/421302) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butler M. W., McGraw K. J. 2010. Past or present? Relative contributions of developmental and adult conditions to adult immune function and coloration in mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). J. Comp. Physiol. B. 10.1007/s00360-010-0529-z (doi:10.1007/s00360-010-0529-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garamszegi L. Z., Eens M., Török J. 2008. Birds reveal their personality when singing. PLoS ONE 3, e2647. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002647 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002647) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Godin J.-G. J., Dugatkin L. A. 1996. Female mating preference for bold males in the guppy Poecilia reticulata. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 10 262–10 267 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10262 (doi:10.1073/pnas.93.19.10262) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stankowich T. 2003. Marginal predation methodologies and the importance of predator preferences. Anim. Behav. 66, 589–599 10.1006/anbe.2003.2232 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2232) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Phillips B. L., Kelehear C., Pizzatto L., Brown G. P., Barton D., Shine R. 2010. Parasites and pathogens lag behind their host during periods of host range advance. Ecology 91, 872–881 10.1890/09-0530.1 (doi:10.1890/09-0530.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cote J., Clobert J., Brodin T., Fogarty S., Sih A. 2010. Personality-dependent dispersal: characterization, ontogeny and consequences for spatially structured populations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 4065–4076 10.1098/rstb.2010.0176 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0176) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Riain M. J., Jarvis J. U. M., Faulkes C. 1996. A dispersive morph in the naked mole rat. Nature 380, 619–621 10.1038/380619a0 (doi:10.1038/380619a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aragón P., Meylan S., Clobert J. 2006. Dispersal status-dependent response to the social environment in the Common Lizard Lacerta vivipara. Funct. Ecol. 20, 900–907 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01164.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01164.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suhonen J., Honkavaara J., Rantala M. J. 2010. Activation of the immune system promotes insect dispersal in the wild. Oecologia 162, 541–547 10.1007/s00442-009-1470-2 (doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1470-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown C. R., Brown M. B. 1992. Ectoparasitism as a cause of natal dispersal in cliff swallows. Ecology 73, 1718–1723 10.2307/1940023 (doi:10.2307/1940023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Layé S., Parnet P., Goujon E., Dantzer R. 1994. Peripheral administration of lipopolysaccharide induces the expression of cytokine transcripts in the brain and pituitary of mice. Mol. Brain Res. 27, 157–162 10.1016/0169-328X(94)90197-X (doi:10.1016/0169-328X(94)90197-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rivest S. 2001. How circulating cytokines trigger the neural circuits that control the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Psychoneuroendocrinol 26, 761–788 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00064-6 (doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00064-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Graciarena M., Depino A. M., Pitossi F. J. 2010. Prenatal inflammation impairs adult neurogenesis and memory related behavior through persistent hippocampal TGFβ1 downregulation. Brain Behav. Immun. 24, 1301–1309 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.06.005 (doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2010.06.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hao L. Y., Hao X. Q., Li S. H., Li X. H. 2010. Prenatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide results in cognitive deficits in age-increasing offspring rats. Neuroscience 166, 763–770 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.006 (doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]