Abstract

Fatty acid synthase (FASN), a key metabolic enzyme for liponeogenesis highly expressed in several human cancers, displays oncogenic properties such as resistance to apoptosis and induction of proliferation when overexpressed. To date, no mechanism has been identified to explain the oncogenicity of FASN in prostate cancer.

We generated immortalized prostate epithelial cells (iPrEC) overexpressing FASN, and found that 14C-acetate incorporation into palmitate synthesized de novo by FASN was significantly elevated in immunoprecipitated Wnt-1 when compared to isogenic cells not overexpressing FASN. Overexpression of FASN caused membranous and cytoplasmic β-catenin protein accumulation and activation, while FASN knockdown by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) resulted in a reduction in the extent of β-catenin activation. Orthotopic transplantation of iPrEC cells overexpressing FASN in nude mice resulted in invasive tumors that overexpressed β-catenin.

A strong significant association between FASN and cytoplasmic (stabilized) β-catenin immunostaining was found in 862 cases of human prostate cancer after computerized subtraction of the membranous β-catenin signal (P<0.001, Spearman’s rho=0.33). We propose that cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin through palmitoylation of Wnt-1 and subsequent activation of the pathway is a potential mechanism of FASN oncogenicity in prostate cancer.

Keywords: β-catenin, Fatty Acid Synthase, Prostate cancer, Image analysis, Immunohistochemistry, Palmitoylation, Wnt1

Prostate cancer is the most prevalent non cutaneous malignancy in males in the U.S. Prostate cancer has also been associated with obesity, high fat intake and the so-called metabolic syndrome.1–3 Fatty acid synthase (FASN) is a key enzyme for liponeogenesis in the metabolic syndrome.4

Cancer cells display increased anaerobic glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen (the so-called Warburg effect), as well as significantly increased de novo synthesis of fatty acids through FASN.5 In fact FASN is minimally expressed in most normal human tissues with the exception of the liver and adipose tissue while up-regulation of FASN is a common feature of many tumor cell-lines and tissues. In addition, FASN overexpression has been correlated to poor prognosis or shorter disease free survival in patients with several human malignancies.6–12 In the prostate, FASN overexpression has been associated with both early and late phases of carcinogenesis. In vitro, the expression of FASN in the androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells LNCaP is enhanced by androgens whereas silencing of the FASN gene by RNA interference induces apoptosis.13,14 In vivo, prostate adenocarcinomas with FASN up-regulation display a more aggressive biologic behavior.15,16 The overexpression and copy number gain of the FASN gene were also demonstrated in tissues from prostate cancer patients and associated with different molecular tumor signatures.8,17 In addition, high cellular levels of FASN in prostate cancer samples were inversely correlated with the expression of PTEN and were associated with activation and nuclear localization of Akt.18,19 Taken together these observations suggest that FASN overexpression confers selective growth advantage to prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Nevertheless, no specific mechanism has been identified so far to explain the oncogenicity of FASN in prostate cancer.

The principal enzymatic product of FASN is palmitic acid.20 Palmitoylation, as well as other lipid modifications such as myristoylation, represent key regulatory switches in most signal transduction pathways including the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.21,22β-catenin is a dual function member of the Wnt signaling pathway that exists in three cellular pools: at the membrane where it is involved in cell-cell adhesion and in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus where it acts as a transcription factor activator.23 In the absence of Wnt signal, β-catenin is bound to the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC)/Axin/GS3Kβ complex, phosphorylated and then degraded through the ubiquitin/proteasome system.24 Under activated Wnt signaling or in case of β-catenin gene mutations, the protein does not complex to APC, it stabilizes in the cytoplasm, it is carried into the nucleus where it activates members of the Tcf/Lef transcription factor family and can be in equilibrium with the cytoplasmic pool.23 In the prostate, β-catenin promotes androgen signaling through its ability to bind to the androgen receptor and activate transcription of androgen-regulated genes.25,26 In vitro, β-catenin is overexpressed in several prostate cancer cell-lines, while, in vivo, activation of the APC gene and stabilization of β-catenin in the murine prostate result in prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (PIN) and prostate cancer.27–29 Overexpression of β-catenin in prostate cancer tissues also correlates with advanced stage and hormone refractory progression of the disease.29,30 β-catenin is thus involved in prostate carcinogenesis despite the evidence that less than 5% of human prostate cancer harbor mutations of this gene.31,32 Subcellular localization of the β-catenin protein is also peculiar in prostate cancer compared to other epithelial tumors: it has been described as membranous and cytoplasmic while its nuclear expression is seen rarely if at all.29,33,34 Here we hypothesized that FASN overexpression in immortalized human prostate epithelial cells (iPrEC) cells would lead to a specific pattern of palmitoylation involving the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. We then analyzed the relationship between FASN and β-catenin in orthotopic xenografts of androgen receptor-expressing iPrEC cells (AR-iPrEC) overexpressing FASN and in human prostate cancer cell-lines and tissue samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of FASN-overexpressing immortalized prostate epithelial cells and culture conditions

Immortalized human prostate epithelial cell lines (iPrEC) and androgen receptor (AR) expressing iPrEC (AR-iPrEC) were engineered. The human FASN cDNA (7536 bp) was generated, sequenced and subcloned into the pBabe retroviral vector containing a puromycin resistance gene (Addgene, Cambridge, MA). To obtain stable FASN-expressing cell lines, 293T-packaging cells plated in 60 mm dishes were co-transfected with the retroviral vector pBabe-FASN (2ug) and the packaging plasmid pCL (1ug) using the Fugene 6 transfection agent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Cells were transduced through infection using 10mg/mL polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, MO); at 48 hr after infection, 2ug/mL puromycin (Sigma) was added to the culture medium to select for puromycin-resistant cells. Cells infected with pBabe vector alone (iPrEC-vector or AR-iPrEC-vector) were used as control. iPrEC and AR-iPrEC cell lines were grown in PrEBM medium obtained from Cambrex Bioscience (Walkersville, MD).

Protein labeling, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting

iPrEC-vector and iPrEC-FASN cells were starved for 3 hrs and then pulsed for 2–3 hr in medium containing 0.3 mCi/ml of 3[H]-palmitate (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). Labeled cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50mM Tris, 1mM EDTA, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.1%SDS) containing complete protease inhibitor mix with EDTA (Roche), 1mM Na3VO4, 1mM NaF, and the whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE under non reducing conditions. For immunoprecipitation, the lysates were cleared with protein A- or G-Sepharose. Anti-Wnt1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was incubated for 1 h at 4 C, followed by overnight incubation with protein A- or G-Sepharose. Finally, the beads were washed with lysis buffer and immune complexes were subjected to SDS-PAGE under non reducing conditions. Gels were transferred to PVDF membrane and then exposed to BioMax MS Film using intensifying screens for 2–7 days at −80°C.

Wnt-1 palmitoylation assay

iPrEC-vector and iPreC-FASN cells (at 70% confluence) were washed twice with PBS, then pulsed for 24 hr in medium containing 2 uCi/ml of [2-14C] acetate sodium (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Labeled cells were lysed in RIPA buffer. After 30 min at 4°C, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm. Protein quantification was performed and 500ug of proteins were used for immunoprecipitation. After 1 hr pre-clearing with protein G-Sepharose, anti-Wnt 1 polyclonal antibody (Zymed, Invitrogen, Rockville, MD) was incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by 1 hr incubation with protein G-Sepharose.

Purified rabbit IgG were used as negative control of immunoprecipitation. Immune complexes were collected by centrifugation, washed five times in lysis buffer, and resuspended in 300μl of lysis buffer. Each sample was placed in a vial filled with liquid scintillation mixture and counted in a beta counter (Beckman 5801 LS). Mean cpm in immune complex from lysates of iPrEC-vector and iPrEC-FASN subtracted the background count (cpm in the negative control sample) were measured.

Western blotting

iPrEC and AR-iPrEC cells were lysed in RIPA buffer. Cellular debris was then pelleted by centrifugation, and supernatants were quantitated using a Bradford protein assay (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein were resolved on a precast 4–12% Tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen), and transferred to Hybond nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes were blocked for 1 hour in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and then incubated overnight with the primary antibody. The following antibodies were used: anti-FASN, anti-β catenin, (both from BD Transduction laboratories, San Diego, CA) at 1:1,000 dilution, anti-active β catenin (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 1:2,000 dilution, and anti-β actin antibody (Sigma) at 1:5,000 dilution. After incubation with peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad), blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) and exposed to X-ray films (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

RNAi

To stably suppress FASN, we used pLKO.1 lentiviral constructs containing 3 different shRNA sequences generated by the RNAi Consortium (shFASN#1: CATGGAGCGTATCTGTGAGAA, shFASN#2: CGAGAGCACCTTTGATGACAT, shFASN#3: CCTCCCACAATTAAACCGCAT). Lentiviral infections were performed as previously described with some modifications. 35 Briefly, 0.5×106 293T cells were seeded in 60 mm dishes. The following day the 293T cells were transfected using Fugene 6 (Roche) with PLKO.1 plasmids simultaneously with packaging plasmids gag-pol and VSV-g. The media containing the progeny virus released from the 293T cells was collected and used to infect target cell-lines (LNCaP, CL1, PC3 and DU145) for 3–6 hours in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma). The target cells were selected with 2ug/ml of puromycin (Sigma Aldrich) for 48 hours, incubated for additional 48 hours without puromycin and then lysed for western blotting analysis. Three different shRNAs were utilized (data not shown) and the shFASN #2 was selected as the optimal, since it resulted in the most profound knockdown of the target. The experiments were performed in triplicate, showing comparable results.

Xenografts

AR-iPrEC-FASN (5×106) were injected orthotopically in six-week-old immunodeficient mice into the anterior lobe of prostate tissue as previously described.36 Tumor size was monitored every 3 days and mice were sacrificed when the tumor size reached a diameter of ~1.5 cm.

Histological samples

A series of 862 men who underwent radical prostatectomy was used to assess the correlation between the expression of FASN and β-catenin. At least 3 cores from each prostate cancer sample were included in 9 high-density tissue microarrays (TMAs). Benign prostate tissue cores (n=40) were also included in the TMAs. The men were participants in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/hpfs/) and the Physicians’ Health Study (http://phs.bwh.harvard.edu/), and were diagnosed with prostate cancer between 1982 and 2004. The median age (SD) at cancer diagnosis was 66 (3.7 years). 61% of the cases were Gleason 7, and 15% Gleason 8 to 10. Quality control specimens were included in each array to assess possible drift or batch variability in staining.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence experiments, 5×104 cells were seeded in four-well chamber slides (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) for 24 hr. Cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at RT, and permeabilized with PBS/0.1% Triton X 100 for 5 min at RT. After 2 washes with PBS, cells were blocked with PBS/1% BSA for 1 hr, followed by incubation with the primary antibody diluted in PBS/1% BSA for 1 hr at RT. The antibodies used were anti-β catenin, (BD Transduction laboratories, 1:100 dilution) and anti-active β catenin (Millipore, 1:250 dilution). Cells were rinsed three times with PBS and then incubated with Texas-Red anti mouse IgG (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA, 1:200 dilution) for 1 hr at RT. Cells were washed three times, followed by incubation with 1uM Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) for 5 min and three additional washes. Finally, the chamber slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector laboratories). Cells were imaged at ×63 with a Plan-Apochromat oil immersion lens on an Axioplan 2 Apoptome epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

Four μm thick sections were cut from each TMA and from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded xenograft tumor samples and used for subsequent immunohistochemical analysis. Sections were incubated using a rabbit polyclonal antibody for FASN (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI, diluted 1:400) and a mouse monoclonal antibody for β-catenin (Dako, Hamburg, Germany, diluted 1:200). Antigen retrieval for FASN was performed in microwave for 15 minutes in citrate buffer. Antigen retrival for β-catenin was performed in pressure cooker at 120° for 5 minutes in citrate buffer. Antigen-antibody reactions were revealed with standardized development times using the streptavidin method with diaminobenzidine (DAB) as substrate on an automated Biogenex i6000 immunostainer (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA).

QD-labeled anti-rabbit (Qdot 605nm, yellow) and anti-mouse (Qdot 655nm, red) IgG antibodies (Invitrogen) were used for QDot multiplex immunostaining. Signal was detected using a Leitz Diaplan fluorescence microscope and a CRI Nuance spectral analyzer (CRI Inc., Woburn, MA). Image files were collected at 5-nm wavelength intervals from 450 to 700 nm. The composite image file was deconvoluted using the spectra of autofluorescence and the QD emission spectrum, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Computer-based image analysis system for immunohistochemical scoring of TMAs

TMA slides were scanned using the Ariol instrument SL-50 (Applied Imaging, Grand Rapids, MI) and tumor areas of each core were selected for quantitative analysis. FASN and β-catenin immunostainings were quantitatively scored by Ariol as the area of staining. Linear progressive values were obtained from each core and finally normalized using a logaritmic scale. Total and membrane β-catenin stainings were then analysed separately by the Ariol and the cytoplasmic area was obtained by subtracting the membrane from the total staining. Finally, the area of cytoplasmic β-catenin was normalized using a logaritmic scale.

Statistical analyses

FASN and β-catenin expression scores were summarized as mean (std) and median (range) of values for the normal and tumor samples. Comparisons between the paired normal and tumor samples were conducted using Wilcoxon signed rank test. The association between FASN and cytoplasmic β-catenin was statistically evaluated using a two sided Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Two-tailed P value <.05 was used to define statistical significance. The statistical analysis was undertaken using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Statistical significance of the results of the palmitoylation assay was determined by using 1 tail t-test and GraphPad Prism 4.0 software.

RESULTS

Stable overexpression of FASN in immortalized human prostate cells results in a unique pattern of protein palmitoylation

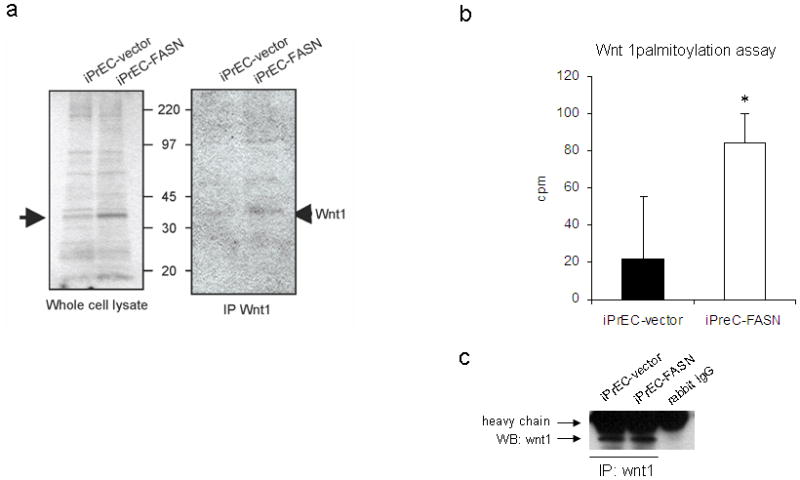

We first sub-cloned the human FASN cDNA (7536 bp) into a pBabe retroviral vector and used it to infect immortalized prostate epithelial (iPrEC-FASN) cells. iPrEC-FASN and iPrEC-vector cells were supplemented with exogenous 3H-palmitate, the main product of FASN activity. Cell lysates of iPrEC-FASN cells showed different levels of palmitoylation of a variety of as yet unidentified proteins when compared to iPrEC-vector (Figure 1a left). A high level of palmitoylation of a band of approximately 45 Kd, corresponding to Wnt1, was found in iPrEC-FASN cells after immunoprecipitation (Figure 1a right).

Figure 1.

Substantiation of the hypothesis that Wnt1 is palmitoylated in iPrEC cells stably overexpressing FASN. (a) Overexpression of FASN led to a specific pattern of palmitoylation in lysates of iPrEC-FASN compared to iPrEC-vector cells pulsed in medium containing 3H-palmitate (left panel). A band of approximately 45 kD corresponding to Wnt1 was revealed after immunoprecipitation (right panel). (b) The Wnt 1 palmitoylation assay showed increased incorporation of labeled acetate in immunoprecipitated Wnt-1 in iPrEC-FASN compared to iPrEC-vector cells. Cpm in Wnt 1 immune complex samples after subtraction of the background (cpm in the negative control sample: rabbit purified igG immunoprecipitation) are shown in the graph. Error bars represent mean standard error (P<0.05). (c) Representative western blotting of immunoprecipitatated Wnt-1 in the same samples used for the palmitoylation assay.

We thus hypothesized that FASN overexpression would lead to a specific pattern of palmitoylation of Wnt 1, an upstream key regulator of β-catenin, in tumor cells.

FASN dependent-activation of Wnt1 occurs via its palmitoylation

In order to assess whether FASN was responsible for the increase in Wnt1 palmitoylation we quantified the incorporation of labeled acetate, the required precursor of palmitate in de novo fatty acid synthesis. iPrEC cells stably overexpressing FASN showed significantly increased incorporation of 14C-acetate in immunoprecipitated Wnt-1 (Figure 1b–c).

The result of the Wnt1 palmitoylation assay suggests that a portion of the palmitate synthesized de novo by FASN in iPrEC-FASN cells is utilized for the palmitoylation of Wnt-1 which may affect, at least in part, the activation of β-catenin.

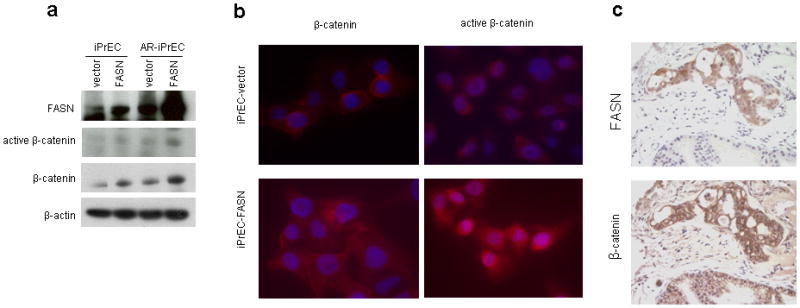

FASN overexpression in immortalized prostate epithelial cells results in activation and stabilization of β-catenin

We then assessed whether, palmitoylation of Wnt1 was associated with activation of β-catenin. Significantly, higher levels of β-catenin protein were detected in iPrEC-FASN and AR-iPrEC-FASN cells compared to the control cells (Figure 2a). In addition, using a specific antibody for the active form of the protein, i.e. an antibody raised against Ser37-and Thr41-dephosphorylated β-catenin, we also found that β-catenin was activated in iPrEC-FASN and AR-iPrEC cells compared to the control cells (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

In vitro and in vivo stabilization and activation of β-catenin in immortalized prostate cells stably overexpressing FASN. (a) Immunoblot analysis of FASN and β-catenin in iPrEC-FASN and AR-iPrEC-FASN cell lines and their respective controls. An increase of β-catenin total expression and a slight increase of its activated form were observed in correspondence to FASN overexpression. (b) a predominant cytoplasmic staining for total and active β-catenin was detectable by immunofluorescence in iPrEC-FASN cells (bottom pictures) while the signal in iPrEC-vector (top pictures) was mainly at the membrane (DAPI-Texas Red staining, ×63 magnification). (c) Co-localization between mixed membrane/cytoplasmic staining for β-catenin and FASN was found by immunohistochemistry in AR-iPrEC-FASN xenograft tumors. The upper panel shows intense immunostaining for FASN in the tumor cells and no staining in the normal surrounding mouse prostate tissue. The lower panel shows mixed membrane/cytoplasmic staining for β-catenin in the tumor cells and exclusively membrane staining in the surrounding normal mouse prostate glands (DAB, ×200 magnification).

Immunofluorescence staining for total β-catenin showed a mixed cytoplasmic and membrane positivity in iPrEC-FASN compared with a predominant membrane staining in iPrEC-vector cells (Figure 2b left). Accordingly, an increased cytoplasmic staining for the active form of β-catenin was detected in iPrEC-FASN compared to iPrEC-vector cells (Figure 2b right).

Taken together, these observations demonstrate that β-catenin is up-regulated and stabilized in immortalized human prostate cells overexpressing FASN in vitro.

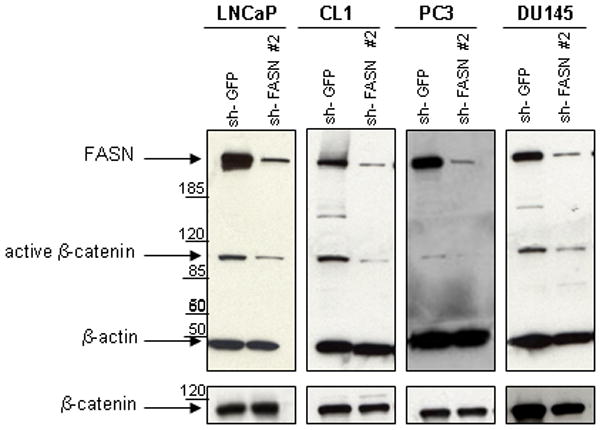

FASN knockdown causes inactivation of β-catenin in androgen-dependent and independent prostate cancer cells

To assess the effect of FASN downregulation on β-catenin activity, we checked the expression of the active form of β-catenin after knockdown of FASN by shRNA in androgen-dependent (LNCaP) and androgen-independent (CL-1, PC3, DU145) prostate cancer cell-lines.

Figure 3 shows that downregulation of FASN by shRNA is consistently associated with decreased expression of the active form of β-catenin in all the cell-lines examined. In contrast, the expression of total β-catenin did not change after FASN knockdown. Four days after the infection with FASN shRNA, cells were still viable but showed a slower growth rate than the control cells infected with GFP-shRNA (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Activation and expression of β-catenin in FASN-knockdown human prostate tumor cell-lines. Treatment of LNCaP, CL1, PC3 and DU145 prostate cancer cell-lines with a shRNA against FASN resulted in marked down-regulation of FASN. A significant decrease of the active form of β-catenin was found in all the prostate cancer cell-lines after 4 days since the infection with the pKLO.1 plasmid encoding the sh-FASN #2. No significant difference in total β-catenin expression levels was observed after FASN inhibition.

This experiment strongly suggests that the activation of β-catenin is modulated by FASN levels in prostate cancer cell-lines.

Association of FASN and cytoplasmic β-catenin in AR-iPrEC-FASN cells orthotopically transplanted in vivo

To confirm the association between FASN and β-catenin in vivo we created an orthotopic (anterior lobe) xenograft prostate tumor model by injecting the AR-iPrEC-FASN cells in nude mice. AR-iPrEC-FASN cells formed invasive adenocarcinoma in mouse prostate tissue with 90% efficiency, while AR-iPrEC-vector cells formed tumors in about 30% of injected mice (data not shown). In addition, immunohistochemical analysis of FASN and β-catenin in these tumors showed co-localization of the two proteins (Figure 2c). Both membrane and cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin was observed in these tumors while nuclear immunostaining was never detected.

Thus, the stabilized cytoplasmic fraction of β-catenin co-localizes with FASN in the cytosol of the AR-iPrEC-FASN xenograft tumors.

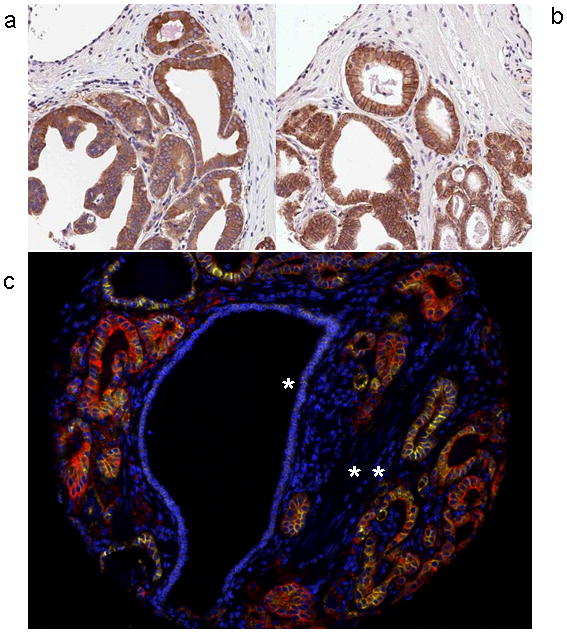

FASN and stabilized β-catenin are co-expressed in the cytoplasm of human prostate cancer specimens

We next determined whether high FASN levels correlate with stabilized β-catenin by immunohistochemical staining in TMAs containing 862 cases of prostate cancer and representative cores of normal prostate tissue. FASN expression in normal prostate tissue was weak and limited to occasional cells in the secretory cell layer. β-catenin immunostaining in normal prostate was always membranous in both basal and secretory cells. Increased FASN expression and increased cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin were significantly associated with prostatic adenocarcinoma compared to paired normal samples (p<0.0001 Wilcoxon test). All the prostate cancer cores showed cytoplasmic staining for FASN and either membranous or cytoplasmic staining for β-catenin, with a considerable variability in the localization of the staining (Figure 4a,b). The co-localization of FASN and β-catenin in the cytoplasm of the same prostate cancer cells was demonstrated using dual quantum dot immunohistochemistry followed by deconvolution by multispectral imaging (Figure 4c). Nuclear localization of β-catenin was never seen by immunohistochemistry in our series of prostate cancers.

Figure 4.

Representative images of immunohistochemistry showing overexpression of FASN (a) and mixed membrane/cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin (b) (DAB, 100X magnification). (c) Pseudo-colorized dual quantum dot imaging of benign prostate epithelium (one star) and prostate adenocarcinoma (two stars). FASN (Qdot 605nm, yellow) and β-catenin (Qdot 655nm, red) were seen to co-localize in the cytoplasm of the prostate adenocarcinoma glands with minimal colocalization and expression in the adjacent benign epithelium (QDots, 100X magnification).

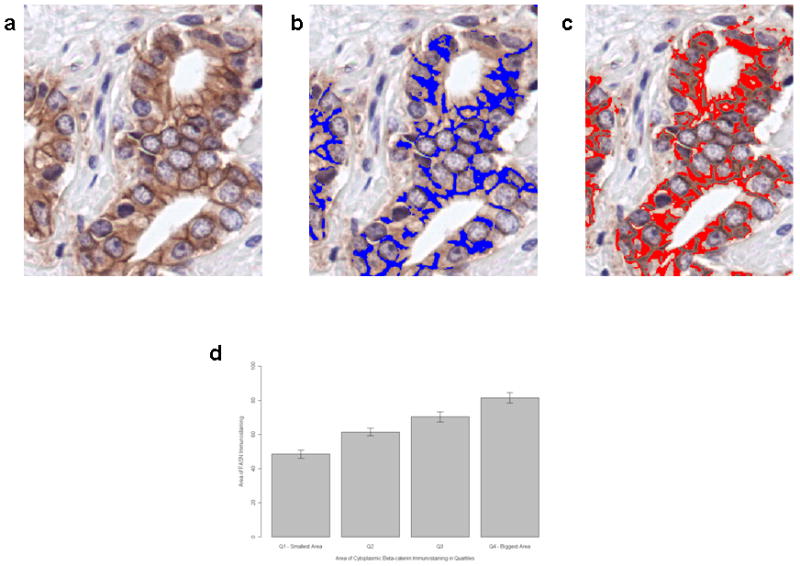

Digital quantitative assessment of FASN and cytoplasmic β-catenin expression

To avoid the bias derived from human scoring both FASN and β-catenin immuno-stainings were acquired and automatically scored by image analysis. Figures 5a,b and c depict how we achieved and quantitated the cytoplasmic immunostaining for β-catenin after digital subtraction of the membrane area from the overall area of immunostaining. A strong significant association was found between FASN immunostaining and cytoplasmic β-catenin (P<0.001, Spearman’s rho=0.33, n=862) (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Quantitative assessment of cytoplasmic β-catenin immunostaining by computerized digital analysis in a case of prostate cancer Gleason grade 3. (a) The section stained for β-catenin is digitally acquired. (b) The membranous immunostaining is pseudo-colorized in blue. (c) The cytoplasmic immunostaining is pseudo-colorized in red and then it can be quantified by digital subtraction of the membranous from the total staining. Finally a score based on the area of staining is generated. (d) Correlation between the area of cytoplasmic β-catenin, divided into quartiles, and the area of FASN immunostaining in serial sections of the same cores (100X magnification).

Overexpression of FASN and cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin are thus strongly associated in human prostate cancer tissues.

DISCUSSION

Prostate cancer is currently the second cause of tumor-related death after lung cancer in U.S. males.1 A diet rich in fat and carbohydrate as well as high body-mass index (BMI) have been correlated to a higher risk of dying from prostate cancer.37 FASN plays a key role in the metabolic conversion of excess dietary carbohydrates into fatty acids and it is overexpressed in prostate cancer. Although several mechanisms of FASN-mediated oncogenicity have been hypothesized, clear pathways linking the activity of this enzyme and cancer have not been elucidated to date. 38,39

Here we hypothesized that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a potential mediator of FASN oncogenicity in the prostate. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has previously been implicated as an oncogenic factor in prostate cancer progression. Wnt proteins are hydrophobic and are post-transcriptionally modified by palmitoylation, thus explaining their poor solubility.40 Furthermore palmitoylation is required for receptor activation by Wnt proteins.21 Our data demonstrated that Wnt-1 palmitoylation is increased in prostate epithelial cells stably overexpressing FASN when compared to their isogenic counterpart, as determined by increased incorporation into Wnt-1 of de novo synthesized 14C-acetate, the precursor of palmitate. FASN-mediated palmitoylation could also affect other transduction pathways apart from Wnt/β-catenin. In addition, since the pattern of palmitoylation in the lysates of FASN overexpressing cells differs from that obtained from untransfected cells, the effects of increased synthesis of palmitate in prostate tumor cells, may have additional pleiotropic effects as a result of palmitoylation and subsequent activation or altered subcellular localization of target proteins.

Our results also show that β-catenin is stabilized in FASN overexpressing cells. The cell lysates of iPrEC-FASN and AR-iPrEC-FASN cells contained higher amounts of total and active β-catenin compared to non FASN-overexpressing cells. The specific antibody for the active form of β-catenin is directed against an epitope containing two of the four non-phosphorylated residues of the protein, which are dephosphorylated when β-catenin is activated.41 Its detection is thus informative for the stabilized, non-phosphorylated form of β-catenin. The evidence of a link between the overexpression of FASN and the activation of β-catenin was in fact supported by a decrease in the active form of β-catenin after FASN knockdown in both androgen-dependent and independent prostate cancer cell-lines. Taken together, these data suggest that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is activated in FASN overexpressing prostate cells and that this activation is associated with an increase in the cytoplasmic fraction of β-catenin.

In order to quantitate the amount of cytoplasmic, i.e. stabilized and activated β-catenin immunostaining in prostate cancer, we developed a computer-based quantitative method. We were able to quantify by image analysis the area of cytoplasmic β-catenin after digital subtraction of the membrane staining from total immunostaining. In normal conditions cytoplasmic β-catenin is bound to the APC/GS3K/Axin complex and degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Under Wnt signaling, the destruction complex disassembles. β-catenin is not phosphorylated and can either accumulate in the cytoplasm or shift into the nucleus to bind transcription factors of the TCF family.23 Once in the nucleus the fate of β-catenin is activation of transcription while a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttle mediated by chaperone proteins occurs.24 Therefore, cytoplasmic β-catenin can be considered a bona fide surrogate of nuclear immunostaining.

Importantly, we show that FASN and the cytoplasmic stabilized form of β-catenin co-localize in human prostate cancer samples. It might be argued that the stabilization of β-catenin in the cytoplasm might result in an increase in the nuclear fraction with subsequent activation of downstream effectors of the Wnt pathway. Nuclear localization of β-catenin has been described in many human solid tumors such as colo-rectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma in association with mutations of the CTNNB1 gene (very rare in prostate cancer).32,33,42 Interestingly, nuclear localization of β-catenin in prostate cancer is a rare event.30,33,34 In fact, we also failed to identify any nuclear staining for β-catenin in our 862 prostate cancer samples. Further, cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin has been previously described in apoptosis-resistant, hormone-refractory prostate cancer.29,30 Thus, cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin can be considered a surrogate of activated β-catenin in prostate cancer.

The androgen receptor (AR) and β-catenin functionally interact and increased AR expression is consistently associated with the development of androgen-independent prostate cancers.25,43 Therefore, β-catenin may play an important role in the maintenance/progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer.44 Interestingly, high levels of FASN, Wnt-1 and β-catenin expression have been previously found to be associated with advanced, metastatic, hormone refractory prostate cancer.8,29 It is tempting to speculate that FASN overexpression may result in β-catenin activation through Wnt1 palmitoylation with subsequent ligand-independent AR activation.

On the basis of our findings, we hypothesized a new model for the mechanism of action of FASN in prostate oncogenesis. We propose that stabilization of β-catenin through the palmitoylation of Wnt1 is a potential effector of FASN oncogenicity in prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work (to ML) was obtained from the National Cancer Institute (PO1CA89021, P50 CA90381 and CA55075), the Prostate Cancer Foundation, DFCI-Novartis Drug Development Program, the Linda and Arthur Gelb Center for Translational Research, a gift from Nuclea Biomarkers to the Jimmy Fund and the Loda lab, and the Samuel Waxman Foundation (SPA P01-Waxman-CS01). Support to MEH from NIH grant GM38903.

GZ and EP are supported by grants from the American-Italian Cancer Foundation. We are grateful to Dr. William C. Hahn for the engineering of the immortalized human prostate epithelial cell lines and to Dr. Phillip Febbo and Dr. Ramesh A. Shivdasani for helpful suggestions.

References

- 1.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. Jama. 2005;293:2095–2101. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson SO, Wolk A, Bergström R, et al. Body size and prostate cancer: a 20-year follow-up study among 135006 Swedish construction workers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:385–389. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.5.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhajda FP, Pizer ES, Li JN, Mani NS, Frehywot GL, Townsend CA. Synthesis and antitumor activity of an inhibitor of fatty acid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3450–3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050582897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusakabe T, Maeda M, Hoshi N, et al. Fatty acid synthase is expressed mainly in adult hormone-sensitive cells or cells with high lipid metabolism and in proliferating fetal cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:613–622. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhajda FP, Jenner K, Wood FD, et al. Fatty acid synthesis: a potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6379–6383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi S, Graner E, Febbo, et al. Fatty acid synthase expression defines distinct molecular signatures in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;10:707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visca P, Sebastiani V, Botti C, et al. Fatty acid synthase (FAS) is a marker of increased risk of recurrence in lung carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:4169–4173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahiro T, Shinichi K, Toshimitsu S. Expression of fatty acid synthase as a prognostic indicator in soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2204–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shurbaji MS, Kalbfleisch JH, Thurmond TS. Immunohistochemical detection of a fatty acid synthase (OA-519) as a predictor of progression of prostate cancer. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:917–921. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:763–777. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swinnen JV, Esquenet M, Goossens K, Heyns W, Verhoeven G. Androgens stimulate fatty acid synthase in the human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1086–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Schrijver E, Brusselmans K, Heyns W, Verhoeven G, Swinnen JV. RNA interference-mediated silencing of the fatty acid synthase gene attenuates growth and induces morphological changes and apoptosis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3799–3804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swinnen JV, Roskams T, Joniau, et al. Overexpression of fatty acid synthase is an early and common event in the development of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:19–22. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein JI, Carmichael M, Partin AW. OA-519 (fatty acid synthase) as an independent predictor of pathologic state in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Urology. 1995;45:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(95)96904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah US, Dhir R, Gollin SM, Chandran UR, Lewis D, Acquafondata M, Pflug BR. Fatty acid synthase gene overexpression and copy number gain in prostate adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van de Sande T, Roskams T, Lerut E, et al. High-level expression of fatty acid synthase in human prostate cancer tissues is linked to activation and nuclear localization of Akt/PKB. J Pathol. 2005;206:214–219. doi: 10.1002/path.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandyopadhyay S, Pai SK, Watabe, et al. FAS expression inversely correlates with PTEN level in prostate cancer and a PI3-kinase inhibitor synergizes with FAS siRNA to induce apoptosis. Oncogene. 2005;24:5389–5395. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhajda FP. Fatty acid synthase and cancer: new application of an old pathway. Cancer res. 2006;66:5977–5980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miura GI, Treisman JE. Lipid modification of secreted signaling proteins. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1184–1188. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.11.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurayoshi M, Yamamoto H, Izumi S, Kikuchi A. Post-translational palmitoylation and glycosylation of Wnt-5a are necessary for its signaling. Biochem J. 2007;402:515–523. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daugherty RL, Gottardi CJ. Phospho-regulation of β-catenin adhesion and signaling functions. Physiology. 2007;22:303–309. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00020.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cong F, Varmus H. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of axin regulates subcellular localization of β-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2882–2887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307344101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Truica CI, Byers S, Gelmann EP. Beta-catenin affects androgen receptor transcriptional activity and ligand specificity. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4709–4713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yardy GW, Brewster SF. Wnt signaling and prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:119–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gounari F, Signoretti S, Bronson R, et al. Stabilization of beta-catenin induces lesions reminiscent of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, but terminal squamous transdifferentiation of other secretory epithelia. Oncogene. 2002;21:4099–4107. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruxvoort KJ, Charbonneau HM, Giambernardi TA, et al. Inactivation of Apc in the mouse prostate causes prostate carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2490–2496. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen G, Shukeir N, Potti A, et al. Up-regulation of Wnt-1 and beta-catenin production in patients with advanced metastatic prostate carcinoma: potential pathogenetic and prognostic implications. Cancer. 2004;101:1345–1356. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de la Taille A, Rubin M, Chen WM, et al. β-catenin-related anomalies in apoptosis-resistant and hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1801–1807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voeller HJ, Truica CI, Gelmann EP. Beta-catenin mutations in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2520–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chesire DR, Ewing CM, Gage WR, Isaacs WB. In vitro evidence for complex modes of nuclear beta-catenin signaling during prostate growth and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:2679–2694. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bismar TA, Humphrey PA, Grignon DJ, Wang HL. Expression of beta-catenin in prostatic adenocarcinomas: a comparison with colorectal adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:557–563. doi: 10.1309/4470-49GV-52H7-D258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horvath LG, Henshall SM, Lee CS, et al. Lower levels of nuclear beta-catenin predict for a poorer prognosis in localized prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:415–422. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moffat DA, Gruenemberg X, Yang SY, et al. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell. 2006;124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berger R, Febbo PG, Majumder PK, et al. Androgen-induced differentiation and tumorigenicity of human prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8867–8875. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright ME, Chang SC, Schatzkin, et al. Prospective study of adiposity and weight change in relation to prostate cancer incidence and mortality. Cancer. 2007;109:675–684. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baron A, Migita T, Tang D, Loda M. Fatty acid synthase: a metabolic oncogene in prostate cancer? J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:47–53. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:763–777. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, et al. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Noort M, Meeldijk J, van der Zee R, Destree O, Clevers H. Wnt signaling controls the phosphorylation status of beta-catenin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17901–17905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiorentino M, Altimari A, Ravaioli M, et al. Predictive value of biological markers for hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with orthotopic liver transplantation. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1789–1795. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeMarzo A, Nelson WG, Isaacs WB, Epstein JI. Pathological and molecular aspects of prostate cancer. Lancet. 2003;361:955–964. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12779-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulholland DJ, Dedhar S, Coetzee GA, Nelson CC. Interaction of nuclear receptors with the Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling axis: Wnt you like to know? Endocr Rev. 2005;26:898–915. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]