Abstract

Iron deficiency in early human life is associated with abnormal neurological development. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of postnatal iron deficiency on emotional behavior and dopaminergic metabolism in the prefrontal cortex in a young male rodent model. Weanling, male, Sprague-Dawley rats were fed standard nonpurified diet (220 mg/kg iron) or an iron-deficient diet (2–6 mg/kg iron). After 1 mo, hematocrits were 0.42 ± 0.0043 and 0.16 ± 0.0068 (mean ± SEM; P < 0.05; n = 8), liver nonheme iron concentrations were 2.3 ± 0.24 and 0.21 ± 0.010 μmol/g liver (P < 0.05; n = 8), and serum iron concentrations were 47 ± 5.4 and 23 ± 7.1 μmol/L (P < 0.05; n = 8), respectively. An elevated plus maze was used to study emotional behavior. Iron-deficient rats displayed anxious behavior with fewer entries and less time spent in open arms compared to control rats (0.25 ± 0.25 vs. 1.8 ± 0.62 entries; 0.88 ± 0.88 vs. 13 ± 4.6 s; P < 0.05; n = 8). Iron-deficient rats also traveled with a lower velocity in the elevated plus maze (1.2 ± 0.15 vs. 1.7 ± 0.12 cm/s; P < 0.05; n = 8), behavior that reflected reduced motor function as measured on a standard accelerating rotarod device. Both the time on the rotarod bar before falling and the peak speed attained on rotarod by iron-deficient rats were lower than control rats (156 ± 12 vs. 194 ± 12 s; 23 ± 1.5 vs. 28 ± 1.6 rpm; P < 0.05; n = 7–8). Microdialysis experiments showed that these behavioral effects were associated with reduced concentrations of extracellular dopamine in the prefrontal cortex of the iron-deficient rats (79 ± 7.0 vs. 110 ± 14 ng/L; P < 0.05; n = 4). Altered dopaminergic signaling in the prefrontal cortex most likely contributes to the anxious behavior observed in young male rats with severe iron deficiency.

Introduction

Iron deficiency is the most common single-nutrient deficiency disease in the world. The greatest prevalence of iron deficiency is found in infants between 6 and 24 mo of age, a stage when rapid brain growth occurs and cognitive and motor skills are developing. Among the numerous biological effects of iron, it is known that iron sufficiency is important for normal neurological function and iron deficiency during infancy, and early childhood is associated with diminished mental, motor, and behavioral functions (1). The effects of iron deficiency in infancy persist even after reversal of anemia with iron treatment (2–6).

Brain iron concentrations are highest in the substantia nigra, globus pallidus, nucleus caudate, red nucleus, and putamen, suggesting that the rapid accumulation of iron observed during the development of the nervous system may participate in behavioral organization (7). The biological basis for functional deficits of iron deficiency have been considered mainly in 3 areas: morphology, neurochemistry, and bioenergetics (8). Iron deficiency in early development affects brain myelination and consequently behavioral development (5, 9–13). Iron is required for the development and function of many neuronal circuits, especially the monoaminergic pathways (6, 14–22). Iron deficiency has also been linked to alterations in γ-amino butyric acid-mediated neurotransmission (20). Metabolism is affected by iron concentrations (23), e.g., the metabolic activity of cytochrome oxidase is reduced in prenatal iron deficiency, thus altering the generation and utilization of metabolic energy in the hippocampus (24).

Given the prevalence of iron deficiency in infants and the susceptibility of the developing brain to nutrient factors, understanding the neurochemical and behavioral effects of iron deficiency is critical to evaluate the metal’s role in mental health. Numerous animal studies have addressed the relationship between iron status and behavior. As early as 1972, decreased activity and disturbed diurnal rhythm were reported in iron-deficient rats (25). Many subsequent studies have consistently shown that iron-deficient animals are hypoactive (26–30). Iron deficiency also was reported to alter the response to environmental stimuli, stereotypic behavior, and exploratory behavior (22, 29, 31–34). Iron-deficient animals display deficits in fear conditioning (35, 36) and impaired spatial memory (6, 34). Other behavioral studies of emotion have led to inconclusive results; Beard et al. observed increased anxiety (37), whereas Eseh and Zimmerberg (38) reported no effect in adult rats with previous iron deficiency. In this investigation, we examined different aspects of behavioral function in the same cohort of young male rats with severe iron deficiency. Changes in neurotransmitter, receptor, and transporter concentrations were also explored with a focus on the dopaminergic pathway in the prefrontal cortex.

Materials and Methods

Animals and diets.

Animal protocols were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Taconic (Taconic Farms) at 3 wk old. Upon receipt, rats were weighed and ranked in order of descending weight. Alternate rats were assigned to be fed either an iron-deficient diet containing 2–6 mg Fe/kg (TD99397, Harlan Teklad) or a control diet containing 220 mg Fe/kg (PicoLab 5053, LabDiet) (Supplemental Table 1). The latter was higher than typically considered adequate (35 mg Fe/kg). Other micronutrients known to influence behavior were present at adequate concentrations in the iron-deficient diet, e.g. zinc (36 mg/kg) and vitamin A (1.7 μg/g). Although higher concentrations of micronutrients were present in the control diet, their ratio to iron was still lower compared to the iron-deficient diet. Impaired behavior due to high iron or interactions with other micronutrients might be reflected in the control rats. In a previous neurobehavioral study of high dietary iron, Sobotka et al. (39) used the same reference level (35 mg Fe/kg) to compare behavior in rats fed higher iron diets of 350, 3500, and 20,000 mg/kg. Significant impairment was observed only at 20,000 mg Fe/kg, nearly 100 times greater than the concentration used in our experiments.

Rats were maintained on a 12-h-light/-dark cycle and consumed reverse osmosis deionized water ad libitum. Daily food consumption by the iron-deficient group was measured and the amount of food provided to the control group was adjusted to 120–125% to maintain the same body weight between 2 groups (pair-feeding). Behavioral tests were performed between postnatal d 45 and 52. At the end of the study, rats were killed by isoflurane overdose followed by exsanguination for collection of blood, liver, and brain tissues to analyze hematocrit, nonheme iron, and neurochemistry.

Elevated plus maze.

Emotional behavior was tested using an elevated plus maze (EPM, Harvard Apparatus). The apparatus was composed of 2 open arms (45 L × 10 W cm) and 2 closed arms (45 L × 10 W × 50 cm, height of wall). The EPM was 66 cm from the floor. At postnatal d 45, each rat was placed in the center of the maze, facing one of the open arms, and allowed to explore the maze for 5 min. The light intensity was dimmed and the test area was enclosed by black curtains. The latency of the first entry into an open arm, number of entries, and time spent in the center, open, and closed arms were recorded by a CCD camera (Sony Color Camera, 1.3 Lens, 0.7 Lux) and analyzed by Smart software v2.5 (Panlab, Harvard Apparatus). The EPM was cleaned with Quatricide TB (Phamacal Research Laboratories) between each animal test.

Rotarod.

Motor function was assessed with a standard accelerating rotarod device (Panlab, Harvard Apparatus), which consisted of a motor-driven knurled nylon cylinder 6 cm in diameter mounted horizontally 35.5 cm above a padded surface. Before the test, rats were trained on the rotarod with 3 sessions/d, 3 min/trial, with 5-min inter-trial intervals, at fixed speeds after habituation on the stationary rotarod for 1 min. Day 1 training speeds were 4, 7, and 10 rpm; d 2 training speeds were 7, 10, and 13 rpm; and d 3 training speeds were 10, 13, and 16 rpm. On d 4, rats of postnatal d 52 were tested on the rotarod with accelerating speed from 4 to 40 rpm over 5 min or until the rats fell off. Each rat was tested on the rotarod twice with a 10-min inter-trial interval. The rotarod device was cleaned using Quatricide TB between trials. Time on bar and speed attained on the rotarod before falling were recorded and the best score of each rat between 2 trials was used for analysis.

Nonheme iron analysis.

Nonheme iron in plasma and tissues was spectrophotometrically determined and expressed as μmol iron/g of wet tissue weight.

Neurotransmitter analysis.

Brains were micro-dissected to obtain prefrontal cortex and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80° until analysis. Total tissue neurotransmitter concentrations were measured as described (40) using a Shisedo Capcell PAK MG C18 column (50 × 1.5 mm, 3-μm particles, ESA) for separation and ESA Coulochem III for detection.

Microdialysis.

Rats were anesthetized with urethane (1 g/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting). A mid-sagittal incision was made over the skull and a small hole was drilled to expose the dura on the right side to allow for implantation of a guide cannula for the subsequent insertion of a precalibrated 3-mm concentric microdialysis probe (CMA-12 Elite, CMA/Microdialysis) into the right prefrontal cortex (Bregma: AP+3.2 mm, LR–0.8, DV–6.0). Following probe implantation, artificial cerebrospinal fluid (K+ 2.7 mmol/L) was continuously perfused at a rate of 1 μL/min with a Harvard Apparatus infusion pump for 2 h to allow for stabilization of injury-mediated release of neurotransmitters, after which four 20-min baseline samples were collected, followed by sample collection for an additional 60–80 min after s.c. injection of d-amphetamine (1 mg/kg) to stimulate dopamine release. Microdialysates were collected in a protective solution to prevent oxidative degradation (41). Samples were stored at –80° until analyzed as described above.

Western-blot analysis of dopamine receptors and transporters.

Prefrontal cortex was microdissected and homogenized in 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) in the presence of protease inhibitors (Complete Mini Roche). Samples (50 μg protein) were electrophoresed on a 4–15% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Biorad) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore) in SDS-free transfer buffer (2 mmol/L Tris base, 15 mmol/L glycine, 20% methanol). The membrane was blocked in 5 mmol/L Tris base, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.4 containing 5% nonfat dry milk, and incubated in goat anti-human dopamine transporter (DAT) antibody (Santa Cruz; 1:100; Supplemental Fig. 1) or mouse anti-human dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) antibody (Santa Cruz, 1:100) in the same buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 2% nonfat dry milk. As a control for loading, the immunoblot was also incubated with mouse anti-actin (MP Biomedicals; 1:10,000). After washing, blots were incubated with IRDye800-conjugated secondary antibody (Li-COR, 1:10,000) and scanned using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging system (Li-COR). Relative intensities of protein bands normalized to actin were determined using Odyssey version 2.1 software.

Statistical analysis.

Data shown are the means ± SEM and based on power calculations, 6–8 rats/group were used for behavioral studies. Comparisons between groups were performed with either Student’s t test or Wilcoxon’s Rank Sum test as appropriate (NCSS 2004 and PASS 2005). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Body weights, hematocrit, and nonheme iron concentrations.

Young male rats (postnatal d 52) were fed a control (220 mg Fe/kg) or iron-deficient (2–6 mg Fe/kg) diet for 1 mo. Body weights and brain weights did not significantly differ from pair-fed controls (Table 1). Hematocrit and nonheme iron concentrations in serum, liver, and brain were 51–92% lower in rats fed the low-iron diet than in controls (P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of control and rats fed iron-deficient diet for 4 wk (postnatal d 52)1

| Control | n | Iron-deficient | n | |

| Body weight, g | 221 ± 6.4 | 8 | 223 ± 12 | 8 |

| Brain weight, g | 1.9 ± 0.042 | 8 | 1.9 ± 0.061 | 8 |

| Hematocrit, volume fraction | 0.42 ± 0.0043 | 8 | 0.16 ± 0.0068† | 8 |

| Liver nonheme iron, μmol/g | 2.3 ± 0.24 | 8 | 0.21 ± 0.010* | 8 |

| Serum nonheme iron, μmol/L | 47 ± 5.4 | 8 | 23 ± 7.1* | 8 |

| Brain nonheme iron, μmol/g | 0.19 ± 0.026 | 4 | 0.12 ± 0.012* | 4 |

Values are means ± SEM. †Different from control, < 0.05 (Wilcoxon's Rank Sum test); *different from control, P < 0.05 (2-tailed Student's t test).

Elevated plus maze.

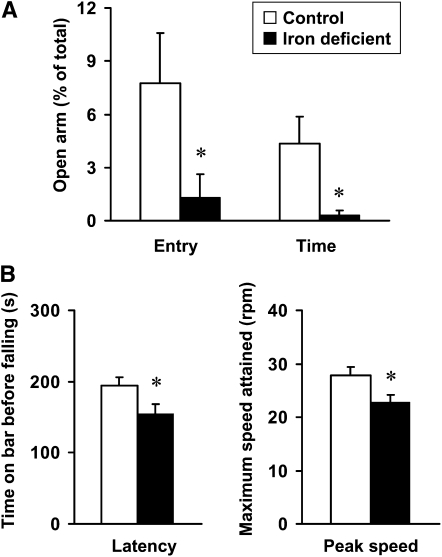

To compare the emotional behavior of iron-deficient and control rats, an elevated plus maze was used to test anxiety beginning at postnatal d 45. Rats fed the low-iron diet had fewer entries into open arms and spent less time in open arms (Fig. 1). Iron-deficient rats traveled with a lower velocity (P = 0.021) (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Elevated plus maze (A) and standard accelerating rotarod (B) tests of behavior and motor coordination of rats fed a control or iron-deficient diet for 4 wk on postnatal d 45 and 52, respectively. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 8. *Different from control, P < 0.05 (Wilcoxon’s Rank Sum test).

TABLE 2.

Behavior in elevated plus maze of rats fed control and iron-deficient diet (postnatal d 45)1

| Control | Iron-deficient | |

| Entries, n | ||

| Open arm | 1.8 ± 0.62 | 0.25 ± 0.25† |

| Closed arm | 9.5 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.0* |

| Central area | 11 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 1.0* |

| Total | 22 ± 2.3 | 9.9 ± 2.2* |

| Time, s | ||

| Open arm | 13 ± 4.6 | 0.88 ± 0.88† |

| Closed arm | 256 ± 10 | 265 ± 10 |

| Central area | 31 ± 5.6 | 34 ± 9.4 |

| Latency, s | 153 ± 56 | 264 ± 36 |

Values are mean ± SEM, = 8. †Different from control, P < 0.05 (Wilcoxon's Rank Sum test); *different from control, P < 0.05 (2-tailed Student's t test).

Rotarod.

To evaluate the effect of iron deficiency on motor function, rats were tested at postnatal d 52 on an accelerating rotarod. Iron-deficient rats fell off the rotarod sooner than control rats (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). The peak speed attained on the rotarod by iron-deficient rats was less than that attained by control rats (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B).

Neurotransmitter concentrations in the prefrontal cortex.

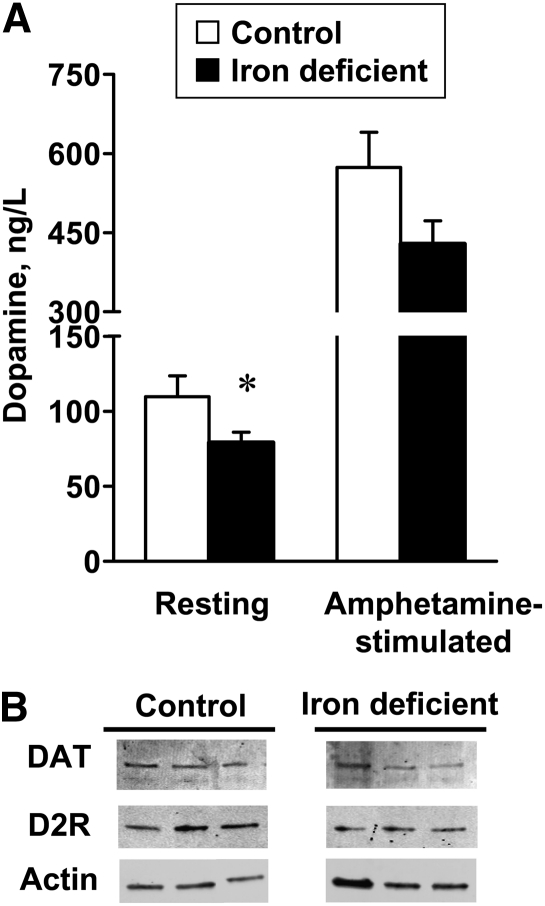

Tissue serotonin in the prefrontal cortex did not differ between control (374 ± 18 ng/g) and iron-deficient rats (459 ± 50 ng/g, P = 0.19; n = 4/group). Tissue dopamine also did not differ between control (107 ± 46 ng/g) and iron-deficient rats (61 ± 15 ng/g, P = 0.40; n = 4/group). Microdialysis experiments demonstrated resting concentrations of extracellular dopamine were significantly lower in iron-deficient rats compared to controls (Fig. 2A). When stimulated by amphetamine, extracellular dopamine in the prefrontal cortex increased to the same extent for control (5.5-fold) and iron-deficient rats (5.3-fold); extracellular dopamine remained lower in iron-deficient rats since the basal resting concentration was reduced compared to controls. No significant changes in dopamine transporters or dopamine receptors were detected by Western-blot analysis of prefrontal cortex lysates (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Microdialysis measurements of extracellular resting and stimulated dopamine (A) and Western-blot analysis of DAT and D2R (B) in prefrontal cortex of rats fed a control iron-deficient diet for 4 wk. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 4. *Different from control, P < 0.05 (Wilcoxon’s Rank Sum test). Western blot shows 3 representative samples with similar results observed for 7–8 different rats in each group. D2R, dopamine D2 receptor; DAT, dopamine transporter.

Discussion

The influence of postnatal iron deficiency on emotional behavior in young male rats was examined. Human studies suggest that anxiety-driven behavior is sensitive to poor iron status. Lozoff et al. (42) observed that anemic infants afflicted with iron deficiency display “increased fearfulness” even after treatment with iron therapy. Deinard et al. (43) showed that infants with even marginal iron deficiency display excessive fearfulness. Beard et al. (37) explored such behavior in a study of young iron-deficient rats at 6 wk of age and observed anxiety-related activities in light/dark box measures of distance traveled, repeated movements, center time, number of nose-pokes, and habituation to a novel environment. These investigators observed that iron-deficient rats moved more rapidly into dark compartments, although the time spent in dark compared to light did not differ from that of control (iron replete) rats. The iron-deficient rats also spent less time in the center of the box and such observations led to the proposal that the young rat is a model organism for behavioral studies to explore the influence of iron deficiency on brain function (37), particularly given the similarity of behaviors observed in iron-deficient children (42, 44). In this study, the elevated plus maze model was used to test for anxious behaviors based on avoidance of open and elevated spaces. Our results strongly support the idea that young male rats with severe iron deficiency display anxious behavior.

Eseh and Zimmerberg (38) also tested the behavioral influences of iron deficiency using ultrasonic vocalization to study rat pups born to iron-deficient or control dams. Although iron deficiency was associated with more distress calls, when later supplemented with iron, these rat pups did not have anxious responses. We have not tested whether anxious behavior could be reversed by iron supplementation and because our observations were made for postnatal iron deficiency, it is not appropriate to compare these results with observations reported for gestational and/or lactational iron deficiency. Many studies have shown that the period of development during which nutritional deficiency occurs later affects both behavioral and physiological endpoints (45). Interestingly, anxious responses in the elevated plus maze also have been observed in adult rats receiving daily i.p. injections of iron (46). Other behavioral impairments have been reported with dietary iron loading with carbonyl iron diet containing 20,000 mg Fe/kg (39). Clearly, imbalanced iron metabolism plays a critical role in anxiety and emotional behavior.

Another notable observation from our study is that iron-deficient rats also traveled in the elevated plus maze at a significantly lower speed, a result correlating with decreased physical activity (25, 28). Motor performance was directly tested in our study to confirm reduced activity due to iron deficiency. Testing on a standard accelerating rotarod device showed impaired motor function. Decreased physical activity and impaired skeletal motor activity along with reduced motivation caused by iron deficiency are observed in both human and animal studies (25, 27–29, 37, 44, 47–52). Iron deficiency may potentially affect many aspects related to motor function, including but not limited to neurochemistry, skeletal muscle strength, energy production, and oxygen supply. Behavioral alterations in motor performance could reflect the sum of these influences and contribute to the anxious behavior observed in the iron-deficient rats.

Many reports have demonstrated that iron deficiency affects monoaminergic pathways in the brain (53). The anxious behavior and motor dysfunction observed would reflect impaired dopaminergic functions. Iron deficiency has been associated with reduced dopamine receptor densities, but we are only aware of one study that reported findings in the prefrontal cortex (37) showing that D2R but not dopamine D1 receptor densities were reduced as measured by radioactive tracer binding. Western-blot analysis used in our study did not detect any difference in D2R between iron-deficient and control rats. Beard et al. (37) studied rats of similar age (~50 d) to our study cohort and a similar level of diet-induced postnatal iron deficiency was achieved, so the discordant data may simply reflect the different approaches used to detect D2R. Our results suggest that emotional behavior reflects changes in the neurotransmitter dopamine, which was reduced in iron-deficient rats. Although the fold-increase was similar to the amphetamine-evoked response observed in control rats, extracellular concentrations of the neurotransmitter were lower in iron-deficient rats.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine the influence of iron deficiency on extracellular dopamine concentrations in the prefrontal cortex. Previous investigations using microdialysis determined extracellular dopamine increased in the caudate putamen of iron-deficient rats (17, 53). These observations correlated with decreased DAT (18), suggesting that dopamine uptake was affected by iron deficiency in this particular brain region. In contrast, we did not observe decreased DAT in the prefrontal cortex by Western-blot analysis. These combined observations may reflect differential regulation of the transporter by iron in different brain regions. Tissue serotonin in the prefrontal cortex of the iron-deficient rats was similar to controls. The fact that extracellular dopamine is significantly lower compared to control rats prompts the notion that neurotransmitter available for evoked release may be limiting in the prefrontal cortex of iron-deficient rats. Iron is a cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase, a key enzyme in dopamine synthesis; whether its activity is specifically affected in the prefrontal cortex during iron deficiency must be better explored (54).

Male rats were used in this study, because estrogen effects on dopaminergic function in the context of iron deficiency have been reported (55). Establishing specific outcomes of the influence of iron deficiency in the prefrontal cortex will allow future study of gender effects. Whether iron repletion can reverse the behavioral influence of iron deficiency is another important question [reviewed in (56)]. We chose to induce postnatal iron deficiency in 21-d-old weanling rats, since newborn pups have immature development compared to humans with considerable and rapid brain growth until the weaning stage. Our study design was such that weanlings were fed iron-restricted diet to establish a cohort of young male rats (45–52 d old) with severe iron deficiency for behavioral and functional experiments after 4 wk. Future studies should explore supplementation to better understand how iron therapy influences the functional effects observed in the prefrontal cortex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Y.L., J.K., and M.W-R. designed research; Y.L., J.K., M.B., and P.D.B. conducted research; M.B. and T.J.M. contributed to the design of behavioral experiments and neurotransmitter analyses; Y.L. and J.K. analyzed data; Y.L., J.K., and M.W-R. wrote the paper; and M.W-R. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH R01 ES014638 (M.W-R.).

Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Figures 1 are available from the “Online Supporting Material” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at jn.nutrition.org.

Literature Cited

- 1.Beard JL, Connor JR. Iron status and neural functioning. Annu Rev Nutr. 2003;23:41–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Wolf AW. Long-term developmental outcome of infants with iron deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:687–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozoff B, Wolf AW, Jimenez E. Iron-deficiency anemia and infant development: effects of extended oral iron therapy. J Pediatr. 1996;129:382–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Hagen J, Mollen E, Wolf AW. Poorer behavioral and developmental outcome more than 10 years after treatment for iron deficiency in infancy. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwik-Uribe CL, Golub MS, Keen CL. Chronic marginal iron intakes during early development in mice alter brain iron concentrations and behavior despite postnatal iron supplementation. J Nutr. 2000;130:2040–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felt BT, Beard JL, Schallert T, Shao J, Aldridge JW, Connor JR, Georgieff MK, Lozoff B. Persistent neurochemical and behavioral abnormalities in adulthood despite early iron supplementation for perinatal iron deficiency anemia in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;171:261–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Andraca I, Castillo M, Walter T. Psychomotor development and behavior in iron-deficient anemic infants. Nutr Rev. 1997;55:125–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beard J. Recent evidence from human and animal studies regarding iron status and infant development. J Nutr. 2007;137:S524–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu GS, Steinkirchner TM, Rao GA, Larkin EC. Effect of prenatal iron deficiency on myelination in rat pups. Am J Pathol. 1986;125:620–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor JR, Mnzies SL. Relationship of iron to oligodendrocytes and myelination. Glia. 1996;17:83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de los Monteros AE, Korsak RA, Tran T, Vu D. de VJ, Edmond J. Dietary iron and the integrity of the developing rat brain: a study with the artificially-reared rat pup. Cell Mol Biol. 2000;46:501–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beard JL, Wiesinger JA, Connor JR. Pre- and postweaning iron deficiency alters myelination in Sprague-Dawley rats. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:308–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz E, Pasquini JM, Thompson K, Felt B, Butkus G, Beard J, Connor JR. Effect of manipulation of iron storage, transport, or availability on myelin composition and brain iron content in three different animal models. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:681–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Shachar D, Ashkenazi R, Youdim MB. Long-term consequence of early iron-deficiency on dopaminergic neurotransmission in rats. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1986;4:81–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youdim MB, Ben-Shachar D. Minimal brain damage induced by early iron deficiency: modified dopaminergic neurotransmission. Isr J Med Sci. 1987;23:19–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shukla A, Agarwal KN, Chansuria JP, Taneja V. Effect of latent iron deficiency on 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1989;52:730–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beard JL, Chen Q, Connor J, Jones BC. Altered monamine metabolism in caudate-putamen of iron-deficient rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:621–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson C, Erikson K, Pinero DJ, Beard JL. In vivo dopamine metabolism is altered in iron-deficient anemic rats. J Nutr. 1997;127:2282–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erikson KM, Jones BC, Beard JL. Iron deficiency alters dopamine transporter functioning in rat striatum. J Nutr. 2000;130:2831–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beard J, Erikson KM, Jones BC. Neonatal iron deficiency results in irreversible changes in dopamine function in rats. J Nutr. 2003;133:1174–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burhans MS, Dailey C, Beard Z, Wiesinger J, Murray-Kolb L, Jones BC, Beard JL. Iron deficiency: differential effects on monoamine transporters. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8:31–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burhans MS, Dailey C, Wiesinger J, Murray-Kolb LE, Jones BC, Beard JL. Iron deficiency affects acoustic startle response and latency, but not prepulse inhibition in young adult rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:917–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward KL, Tkac I, Jing Y, Felt B, Beard J, Connor J, Schallert T, Georgieff MK, Rao R. Gestational and lactational iron deficiency alters the developing striatal metabolome and associated behaviors in young rats. J Nutr. 2007;137:1043–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Deungria M, Rao R, Wobken JD, Luciana M, Nelson CA, Georgieff MK. Perinatal iron deficiency decreases cytochrome c oxidase (CytOx) activity in selected regions of neonatal rat brain. Pediatr Res. 2000;48:169–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glover J, Jacobs A. Activity pattern of iron-deficient rats. BMJ. 1972;2:627–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson AM, Ng KT. Behavioral effects of iron deficiency in the adult rat. Physiol Behav. 1980;24:561–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youdim MB, Ben-Shachar D, Yehuda S. Putative biological mechanisms of the effect of iron deficiency on brain biochemistry and behavior. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:607–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt JR, Zito CA, Erjavec J, Johnson LK. Severe or marginal iron deficiency affects spontaneous physical activity in rats. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:413–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piñero D, Jones B, Beard J. Variations in dietary iron alter behavior in developing rats. J Nutr. 2001;131:311–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unger EL, Paul T, Murray-Kolb LE, Felt B, Jones BC, Beard JL. Early iron deficiency alters sensorimotor development and brain monoamines in rats. J Nutr. 2007;137:118–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinberg J, Levine S, Dallman PR. Long-term consequences of early iron deficiency in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1979;11:631–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Findlay E, Ng KT, Reid RL, Armstrong SM. The effect of iron deficiency during development on passive avoidance learning in the adult rat. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:1089–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unger EL, Bianco LE, Burhans MS, Jones BC, Beard JL. Acoustic startle response is disrupted in iron-deficient rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;84:378–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourque SL, Iqbal U, Reynolds JN, Adams MA, Nakatsu K. Perinatal iron deficiency affects locomotor behavior and water maze performance in adult male and female rats. J Nutr. 2008;138:931–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McEchron MD, Cheng AY, Liu H, Connor JR, Gilmartin MR. Perinatal nutritional iron deficiency permanently impairs hippocampus-dependent trace fear conditioning in rats. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8:195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gewirtz JC, Hamilton KL, Babu MA, Wobken JD, Georgieff MK. Effects of gestational iron deficiency on fear conditioning in juvenile and adult rats. Brain Res. 2008;1237:195–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beard JL, Erikson KM, Jones BC. Neurobehavioral analysis of developmental iron deficiency in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2002;134:517–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eseh R, Zimmerberg B. Age-dependent effects of gestational and lactational iron deficiency on anxiety behavior in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2005;164:214–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobotka TJ, Whittaker P, Sobotka JM, Brodie RE, Quander DY, Robl M, Byrant M, Barton CN. Neurobehavioral dysfunctions associated with dietary iron overload. Physiol Behav. 1996;59:213–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gamache P, Ryan E, Svendsen C, Murayama K, Acworth IN. Simultaneous measurement of monoamines, metabolites and amino acids in brain tissue and microdialysis perfusates. J Chromatogr. 1993;614:213–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kankaanpää A, Meririnne E, Ariniemi K, Seppala T. Oxalic acid stabilizes dopamine, serotonin, and their metabolites in automated liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2001;753:413–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lozoff B, Brittenham G, Viteri FE, Urrutia JJ. Behavioral abnormalities in infants with iron deficiency anemia. : Pollitt E, Leibel L, Iron deficiency: brain biochemistry and behavior. New York: Raven Press; 1982. p. 183–94 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delinard A, Gilbert A, Dodds M, Egeland B. Iron deficiency and behavioral deficits. Pediatrics. 1981;68:828–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lozoff B, Klein NK, Nelson EC, McClish DK, Manuel M, Chacon ME. Behavior of infants with iron-deficiency anemia. Child Dev. 1998;69:24–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao R, Georgieff MK. Iron in fetal and neonatal nutrition. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12:54–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maaroufi K, Ammari M, Jeljeli M, Roy V, Sakly M, Abdelmelek H. Impairment of emotional behavior and spatial learning in adult Wistar rats by ferrous sulfate. Physiol Behav. 2009;96:343–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinberg J, Dallman PR, Levine S. Iron deficiency during early development in the rat: behavioral and physiological consequences. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1980;12:493–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhatia D, Seshadri S. Anemia, undernutrition and physical work capacity of young boys. Indian Pediatr. 1987;24:133–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwik-Uribe CL, Golubt MS, Keen CL. Behavioral consequences of marginal iron deficiency during development in a murine model. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1999;21:661–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harahap H, Jahari AB, Husaini MA, Saco-Pollitt C, Pollitt E. Effects of an energy and micronutrient supplement on iron deficiency anemia, physical activity and motor and mental development in undernourished children in Indonesia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54 Suppl 2:S114–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoltzfus RJ, Kvalsvig JD, Chwaya HM, Montresor A, Albonico M, Tielsch JM, Savioli L, Pollitt E. Effects of iron supplementation and anthelmintic treatment on motor and language development of preschool children in Zanzibar: double blind, placebo controlled study. BMJ. 2001;323:1389–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Angulo-Kinzler RM, Peirano P, Lin E, Garrido M, Lozoff B. Spontaneous motor activity in human infants with iron-deficiency anemia. Early Hum Dev. 2002;66:67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Q, Beard JL, Jones BC. Abnormal rat brain monoamine metabolism in iron deficiency anemia. J Nutr Biochem. 1995;6:486–93 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yehuda S, Youdim MBH. Brain iron: a lesson from animal models. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:618–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erikson KM, Jones BC, Hess EJ, Zhang Q, Beard JL. Iron deficiency decreases dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in rat brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:409–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCann JC, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relationship between iron deficiency during development and deficits in cognitive or behavioral function. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:931–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.