Abstract

The objective was to determine the relationship between dietary energy density (ED; kcal/g) and measured weight status in children. The present study used data from a nationally representative sample of 2442 children between 2 and 8 y old who participated in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Survey measures included 24-h dietary recall data, measurement of MyPyramid servings of various food groups, and anthropometry. The relationship among dietary ED, body weight status as calculated using the 2000 CDC growth charts, and food intake was evaluated using quartiles of ED. Additionally, other dietary characteristics associated with ED among children are described. Specific survey procedures were used in the analysis to account for sample weights, unequal selection probability, and the clustered design of the NHANES sample. In this sample, dietary ED was positively associated with body weight status in U.S. children aged 2–8 y. Obese children had a higher dietary ED than lean children (2.08 ± 0.03 vs. 1.93 ± 0.05; P = 0.02). Diets high in ED were also found to be associated with greater intakes of energy and added sugars, more energy from fat; and significantly lower intake of fruits and vegetables. Interventions that lower dietary ED by means of increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat consumption may be an effective strategy for reducing childhood obesity.

Introduction

The percent of overweight and obese children in the United States has grown considerably since the 1960s. According to the most recent national data, 21.2% of children aged 2–5 y are considered overweight, with 10.4% considered obese as categorized by CDC-defined BMI percentile cutpoints; in children age 6–11 y, the percentages increase to 35.5 and 19.6%, respectively (1). Given the high prevalence rate of childhood obesity, it is important to identify dietary behaviors and patterns that contribute to this epidemic.

Epidemiological data have suggested that dietary ED3 is related to weight status in U.S. adults (2, 3); however, a recent review summarizes the limited information about this relationship in children (4). In the studies that have been conducted in children, the results are mixed. Findings from 1994–1996 and 1998 CSFII have indicated a positive association between dietary ED and various predictors of childhood obesity; however, this finding was based on self-reported anthropometric measures and measured body weight and height were not used (5). Another earlier analysis of the CSFII found no association between ED and BMI percentile in U.S. children (6). Other epidemiological studies have shown a positive relationship between dietary ED and energy intake in both adults and children (3, 7).

Experimental feeding studies have shown that decreasing the ED of a meal significantly decreases meal energy intake in diverse groups of children ages 3–6 y (8, 9). Following these studies, groups such as the WHO and the American Academy of Pediatrics have made specific recommendations regarding consumption of energy-dense foods in children (10, 11). Both groups recommended that children limit consumption of energy-dense foods in children as a strategy for preventing childhood obesity.

In addition to limiting consumption of high-ED foods, The American Academy of Pediatrics also encourages consumption of low-ED foods, such as fruits and vegetables, and a macronutrient-balanced diet based on the 2005 and 2010 Dietary Guidelines (10, 12). Epidemiological evidence indicates that adults who eat the recommended servings of fruits and vegetables have lower dietary ED as well as lower body weights than those who do not (3).

There has been some controversy regarding the energy cost of consuming diets rich in low-ED foods. Several articles have indicated that low-ED foods, such as fruits and vegetables, have a higher energy cost than high-ED foods, making high-ED foods more affordable for individuals of low socioeconomic status (13, 14). Further, consumption of low-ED foods is positively related to socioeconomic status in adults, whereas consumption of high-ED foods is positively related to obesity in groups of low socioeconomic status (13, 15). Given these findings, socioeconomic status may be an important mediator of the relationship between dietary ED and childhood obesity. The NHANES provides ample information to control for this confounding variable. The present study seeks to investigate these relationships in a representative sample of U.S. children 2–8 y years of age in which height and weight were measured. Longitudinal studies have indicated that unhealthy eating behaviors practiced in early childhood predict patterns in adolescence (16). Children aged 2–8 y were examined to identify early dietary patterns associated with overweight and obesity so that strategies can be designed that target dietary behaviors developed during this important transition period.

Methods

The NHANES.

The NHANES is a large, cross-sectional survey conducted by National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES is designed to monitor the health and nutritional status of noninstitutionalized civilians in the US; data are collected on a continual basis and released in 2-y increments. Complete details regarding the NHANES sampling methodology, data collection, and interview process are available on the NHANES web site (17). Data from the 2001–2002 and 2003–2004 survey cycles were combined for this study to maximize statistical power. These cycles were chosen due to the inclusion of USDA-specified MyPyramid food group servings as part of the dietary data set (12). Specific status codes were used to indicate the quality, reliability, and completeness of the dietary data. Dietary recall data were collected by trained interviewers. Children who participated in the NHANES provided 1 d of dietary recall data during their visit to the Mobile Examination Unit with the assistance of their parent or guardian.

Participants.

For the present analyses, all children aged 2–8 y who had complete dietary and anthropometric data were included; children who were currently breastfeeding or missing outcome measures (BMI percentile) were excluded for a final analytical sample of 2442. Age (in months) at the time of exam, sex, race, physical activity, and socioeconomic status were all provided in the NHANES data set. Socioeconomic status was quantified using PIR, or the family size:family income ratio as a percentage of the poverty threshold.

The outcome measure for this study was weight status as measured by BMI percentile. Age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles based on the 2000 CDC growth charts were calculated from the dataset using a SAS program provided by the CDC (18). Weight status was classified using CDC-defined BMI percentile cutpoints (19). Per these guidelines, children with a BMI less than the 85th percentile were classified as lean, children between the 85th and 95th percentiles were classified as overweight, and children with a BMI greater than the 95th percentile were defined as obese.

Dietary data analysis.

The USDA Food and Nutrition Database, version 2.0, was used to process NHANES dietary data. Dietary ED was calculated by dividing the energy content (in kcal) by weight of foods (or foods + beverages) consumed. There are several methods to calculate ED (20). For this study, ED (kcal/g) was calculated using two methods: 1) using only foods; and 2) using all foods and all beverages excluding water. Water consumption was measured differently between the 2 NHANES cycles, making its intake difficult to calculate. USDA food codes were used to identify which items were foods and which were beverages. Because the mean dietary ED of this population varied significantly by age and sex, age- and sex-specific quartiles of ED were created to examine the relationship among dietary ED, weight status, and other dietary factors. These quartiles were created using food-only ED values.

Food group intake analysis was conducted stratified by age group (one group aged 2–3 y, the other 4–8 y) in accordance with the USDA Dietary Guidelines (12). Food group analysis was based on NHANES-provided MyPyramid serving equivalents. The former MyPyramid and current MyPlate guidelines categorize food intake into food group-specific serving sizes (i.e., cup equivalents for fruits and vegetables; ounce equivalents for grains) to allow for grouping of like foods (i.e., determining total vegetable intake or total grain intake). The NHANES database includes 100% juice and white potatoes toward the total number of cups of fruit and vegetables consumed; however, for this study, fruit and vegetable servings were totaled both with and without juice and white potatoes to determine the impact of juice and potatoes on dietary ED.

Statistical methods.

All data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute). Specific survey procedures were used in the analysis to account for sample weights, unequal selection probability, and clustered design. Because the present study examined a small age range of children, it was not possible to further categorize the children into age, sex, and racial groups and maintain the integrity of the statistical analyses. As such, race was included as a covariate in all statistical models. Chi square tests (SAS PROC SURVEYFREQ) were used to determine the bivariate relationship between various demographic characteristics and outcome measures. All significant relationships were included as covariates in the final models. Categorical variables representing the quartiles of ED were entered into models as indicator variables with the lowest quartile as the referent group. Regression models (SAS PROC SURVEYREG) were used to estimate mean intakes of fruits and vegetables by quartile of dietary ED. To conduct trend tests across levels, variables based on the median values for each quartile were created and used in regression models. All models were adjusted for age, race, sex, physical activity, socioeconomic status, and survey cycle. Results are presented as adjusted means with significance determined at P < 0.05. For reporting purposes, the term “low-ED” diet refers to the lowest quartile of ED; conversely, “high-ED” diet refers to the highest quartile of ED. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Pennsylvania State University.

Results

Weight status and dietary ED.

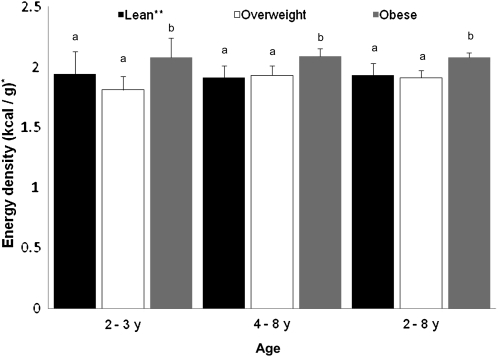

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The sample population for this study was almost identical in percentage of boys and girls; nearly one-third of the sample was overweight or obese, which was similar for both genders. The relationship between dietary ED and body weight status was examined stratified by age group (Fig. 1). The results indicate that dietary ED, calculated using food only, is positively associated with body weight in a combined sample of children aged 2–8 y (Fig. 1). When examining children in all age groups, lean children had lower dietary ED than that of obese children (P = 0.002), calculated using the food-only method. The relationship between dietary ED and other anthropometric measures was also examined (Table 2). The relationship between BMI percentile and dietary ED (food only) differed by age group (P-interaction = 0.04). In children aged 2–3 y, the relationship between BMI percentile and dietary ED was not linear across ED quartiles (P-trend = 0.16); however, in children 4–8 y old, there was a positive linear relationship between prevalence of obesity and dietary ED (P = 0.03). In this age group, children in the lowest quartile of ED (median ED = 1.37) had lower sex- and age-specific BMI percentiles (59th vs. 67th percentile; P = 0.002) than those of children in the highest ED category (median ED = 2.63) after controlling for age in months, race, sex, physical activity, socioeconomic status, and survey cycle. No association was found between weight status and ED when calculated with foods and all beverages (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of children age 2–8 y (NHANES 2001–2004)1

| Variable | n | Weighted n | Weighted % |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1187 | 12,734,336 | 50.1 |

| Female | 1255 | 12,698,107 | 49.9 |

| Age | |||

| 2–3 y | 798 | 6,630,778 | 26.1 |

| 4–8 y | 1644 | 18,801,665 | 73.9 |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 748 | 15,451,312 | 60.8 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 762 | 3,669,073 | 14.4 |

| Mexican American | 698 | 3,467,188 | 13.6 |

| Other | 234 | 2,844,870 | 11.2 |

| Weight status2 | |||

| Lean | 1725 | 18,108,072 | 71.2 |

| Overweight | 363 | 3,670,095 | 14.4 |

| Obese | 354 | 3,654,276 | 14.4 |

| Survey cycle | |||

| 2001–2002 | 1284 | 12,370,581 | 48.6 |

| 2003–2004 | 1158 | 13,061,862 | 51.4 |

Values are unweighted counts, weighted n, and weighted percent. Sample n = 2442 is based on number of observations. Weighted n and weighted percent were determined using NHANES survey weights.

Weight status based on BMI percentile using CDC guidelines; <85th percentile, lean; 85–94.99th percentile, overweight; >95th percentile, obese (19).

FIGURE 1.

Dietary ED by body weight status in children aged 2–8 y (NHANES 2001–2004). Total unweighted n = 2442. Values are means ± SE. Means adjusted for age in months, sex, race, socioeconomic status, physical activity, and survey cycle. Specific survey procedures were applied to account for sample weights and complex survey design. Means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. *Dietary ED, ED (kcal/g), calculated using only food, excluding all beverages. **Lean, overweight, and obese defined using CDC cutpoints base on BMI percentile. Lean, <85th percentile; overweight, 85–95th percentile; obese, >95th percentile (19). ED, energy density.

TABLE 2.

Dietary and anthropometric characteristics of children aged 2–8 y (NHANES 2001–2004)1

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

| Children aged 2–3 y (n = 798) | n = 212 | n = 193 | n = 213 | n = 180 |

| Overall intake2 | ||||

| Median food-only ED, kcal/g | 1.24 | 1.64 | 1.99 | 2.56 |

| Total food energy, kcal/g | 1069 ± 28a | 1148 ± 42b | 1187 ± 60b | 1221 ± 48c |

| Total food + beverage energy, kcal/g | 1397 ± 30a | 1577 ± 56b | 1594 ± 65b | 1627 ± 57c |

| Total beverage energy, kcal/g | 328 ± 16a | 429 ± 19b | 407 ± 19c | 406 ± 28c |

| Total food, g/d | 857 ± 20a | 700 ± 26b | 594 ± 30c | 465 ± 22d |

| Total food + beverages, g/d | 1520 ± 38a | 1570 ± 61a | 1430 ± 51a | 1320 ± 68b |

| Macronutrient intake | ||||

| Fat, % energy | 27.9 ± 0.6a | 31.3 ± 0.5b | 33.3 ± 0.6c | 35.8 ± 1.2d |

| Protein, % energy | 15.2 ± 0.4a | 15.4 ± 0.7a | 13.9 ± 0.3b | 12.7 ± 0.5c |

| Carbohydrate, % energy | 57.9 ± 1.2a | 54.1 ± 1.3a | 52.8 ± 0.9b | 51.6 ± 2.0b |

| Added sugars, tsp/d | 10.8 ± 0.6a | 12.3 ± 1.0a | 13.7 ± 0.8b | 15.4 ± 0.9c |

| Food group intake3 | ||||

| All fruits and vegetables, USDA servings/d | 5.7 ± 0.3a | 4.9 ± 0.3b | 4.1 ± 0.3c | 3.3 ± 0.2d |

| Fruits and vegetables excluding white potatoes and juice, USDA servings/d | 3.6 ± 0.2a | 2.6 ± 0.2b | 1.8 ± 0.1c | 1.0 ± 0.1d |

| Fruit, including juice, cups/d | 1.9 ± 0.1a | 1.7 ± 0.1a | 1.4 ± 0.1b | 1.2 ± 0.1c |

| Vegetables, cups/d | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 0.7 ± 0.1b | 0.7 ± 0.1b | 0.5 ± 0.0c |

| White potatoes, cups/d | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| Grains, oz. equivalents/d | 4.1 ± 0.2a | 4.6 ± 0.2a,b | 4.8 ± 0.2b | 5.1 ± 0.3c |

| Whole grains, oz. equivalents/d | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Total dairy food, including milk and cheese, cups/d | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Milk, cups/d | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| Mean no. times per week you play or exercise hard | 6.6 ± 0.7 | 7.5 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 0.5 | 5.8 ± 0.2 |

| Mean family PIR4 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| Prevalence of obesity5 | 6.3 ± 1.9 | 6.4 ± 2.1 | 12.3 ± 2.7 | 7.9 ± 2.7 |

| BMI percentile | 59.2 ± 4.0a | 61.5 ± 2.1a | 61.1 ± 2.9a | 63 ± 2.8b |

| Children aged 4–8 y (n = 1644) | n = 398 | n = 442 | n = 410 | n = 394 |

| Overall intake | ||||

| Median food-only ED, kcal/g | 1.37 | 1.75 | 2.15 | 2.63 |

| Total food energy, kcal/d | 1410 ± 35a | 1552 ± 48b | 1611 ± 39c | 1569 ± 46d |

| Total food + beverage energy, kcal/d | 1801 ± 43a | 1905 ± 52b | 1993 ± 51b | 1967 ± 54b |

| Total beverage energy, kcal/d | 391 ± 18 | 352 ± 19 | 381 ± 22 | 398 ± 15 |

| Total food, g/d | 1071 ± 29a | 885 ± 27b | 753 ± 19c | 581 ± 19d |

| Total food + beverages, g/d | 1866 ± 53a | 1674 ± 62b | 1582 ± 57c | 1437 ± 41d |

| Macronutrient intake | ||||

| Fat, % kcal | 27.8 ± 0.6a | 31.2 ± 0.5b | 33.9 ± 0.4c | 35.2 ± 0.5d |

| Protein, % kcal | 14.8 ± 0.3a | 14.1 ± 0.3a | 13.0 ± 0.3b | 12.5 ± 0.3b |

| Carbohydrate, % kcal | 58.9 ± 0.8a | 56.1 ± 0.6a | 54.3 ± 0.9b | 53.8 ± 0.8b |

| Added sugars, tsp/d | 18.1 ± 0.8a | 20.0 ± 1.3b | 21.7 ± 0.9b | 22.4 ± 0.9c |

| Food group intake3 | ||||

| All fruits and vegetables, USDA servings/d | 5.8 ± 0.3a | 4.2 ± 0.2b | 3.4 ± 0.2c | 2.8 ± 0.2d |

| Fruits and vegetables (excluding white potatoes and juice), USDA servings/d | 3.8 ± 0.2a | 2.4 ± 0.2b | 1.7 ± 0.1c | 1.1 ± 0.1d |

| Fruit, cups/d | 1.9 ± 0.1a | 1.7 ± 0.1a | 1.3 ± 0.1b | 0.2 ± 0.1c |

| Vegetables, cups/d | 1.1 ± 0.1a | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 0.8 ± 0.1b | 0.7 ± 0.1b |

| White potatoes, cups/d | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Grains, oz. equivalents/d | 5.7 ± 0.3a | 6.4 ± 0.2a | 6.9 ± 0.3b | 7.1 ± 0.2c |

| Whole grains, oz. equivalents/d | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Total dairy food, including milk and cheese, cups/d | 2.6 ± 0.1 a | 2.3 ± 0.1 b | 2.2 ± 0.1 b | 2.2 ± 0.1 b |

| Milk, cups/d | 2.1 ± 0.1a | 1.7 ± 0.1b | 1.5 ± 0.1b | 1.3 ± 0.1c |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| Mean no. times per week you play or exercise hard | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 6.8 ± 0.2 |

| Mean family PIR4 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Prevalence of obesity5 | 12.8 ± 3.1 | 15.5 ± 2.5 | 15.9 ± 3.5 | 21.9 ± 3.5 |

| BMI percentile | 67.6 ± 2.0a | 73.7 ± 1.7b | 67.1 ± 2.7a | 76.1 ± 2.4b |

Data are mean ± SE except as noted. Means in a row with superscripts without a common letter differ, < 0.05. Models adjusted for age, sex, race, physical activity, survey cycle, and socioeconomic status (as measured by PIR). ED, energy density; PIR, poverty:income ratio.

Sample represents unweighted n. Survey weights were applied for all statistical procedures. Q1–Q4 indicates grouping based on quartile cutpoints of dietary ED calculated using food only.

All food group intake values are based on USDA MyPyramid/MyPlate Dietary Guidelines for Americans (12).

PIR calculated by family size.

Unadjusted prevalence of children ≥the 95th percentile of BMI for age and sex is presented (19).

Dietary behaviors by age group and ED category.

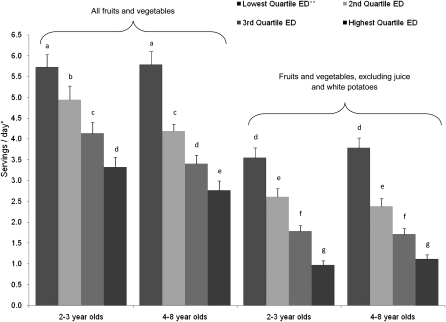

Intake of various food groups was evaluated using MyPyramid equivalent servings (Table 2). In children aged 2–3 y, those with low-ED diets consumed significantly less energy from foods, beverages, and foods and all beverages combined than children with high-ED diets. Despite consuming less energy, these children consumed significantly more grams of food; children in the lowest group consumed nearly double the weight of food as children in the highest group (P < 0.0001) while still consuming less energy. As expected, children with the lowest ED diets consumed significantly less fat, but they also consumed nearly five fewer teaspoons of added sugars than those with the highest ED diets (P = 0.03). Fruit and vegetable intake data were stratified by age (Fig. 2. Children with low-ED diets consumed twice as many servings of fruits and vegetables as children with high-ED diets, with a significant linear trend (P < 0.0001). Examination of the intakes of fruits and vegetables as separate groups indicated that these children consumed twice as many fruits and over twice as many vegetables compared to those with high-ED diets (Table 2). Children with low-ED diets also consumed significantly fewer grains than children with high-ED diets. No differences were observed in total dairy food intake (including milk, cheese, and yogurt), milk intake alone, or whole grain intake.

FIGURE 2.

Fruit and vegetable intake by ED quartile in children aged 2–8 y (NHANES 2001–2004). Total unweighted n = 2442. Data are adjusted mean ± SE. Means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05; significance was calculated using age and fruit/vegetable classification category. Intake was adjusted for age, sex, race, socioeconomic status (as measured by family PIR) physical activity, and survey cycle. *Servings/d is based on USDA dietary guidelines for vegetables measured in cup equivalents (12). **Dietary ED calculated kcal/g. Quartiles of ED were calculated using food only. ED, energy density; PIR, poverty:income ratio.

In the 4–8 y-of-age category, children with the lowest ED diets consumed significantly less energy overall as well as significantly less energy from food than those with the highest ED diets; these children still consumed almost double the weight of food (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Interestingly, there were no observed differences in energy from beverages between children in the lowest ED quartile and those in the highest ED quartile. Children with low-ED diets consumed ~23 g less fat (P < 0.0001) and four fewer teaspoons of added sugars (P < 0.01). In the food group analysis, there was a negative linear relationship between dietary ED and fruit and vegetable consumption (P < 0.0001). Figure 2 shows the relationship between dietary ED and vegetable consumption by age group. Children with low-ED diets consumed twice as many servings of fruits and vegetables as children with high-ED diets (P < 0.0001). When evaluating fruit and vegetable consumption that excluded juice and white potatoes, the difference in consumption between the low- and high-ED groups was even more notable: children in the lowest ED category consumed 2 cups of fruit, whereas children in the high-ED category consumed only 0.2 cups (P < 0.001). In this age group, children with low-ED diets consumed more milk and dairy products (including milk, cheese, yogurt, etc.) than children with high-ED diets (P < 0.01). No differences in whole grain intake or potato intake were observed across categories of ED.

Discussion

In a representative sample of U.S. children, dietary ED was positively associated with body weight in children aged 2–8 y when calculated using the food-only method, excluding all beverages. At present, there is no standardized method for which types of energy sources to use when calculating ED (i.e. foods, beverages, or both); however, most recent publications calculate ED using the food-only method, excluding beverages. Previous studies have indicated that the relationship between ED and body weight is found only when calculating ED using only food (3, 20). In the present study, the data support this notion, as no relationship between the ED of foods and all beverages and body weight was observed. This finding in children is similar to the positive association between dietary ED and body weight found in adults (3, 21–23). Intervention studies in children have found differences between ED and other outcome measures only when calculating ED using only food, excluding beverages (24). An earlier epidemiological study of children reported no association between dietary ED and BMI percentile in children aged 3–5 y (6). There may be several reasons why this finding differs from those in the present study. Like several earlier epidemiological studies, that study (6) focused on data from the 1994–1996 CSFII, which relied on parental reporting of height and weight. The NHANES data includes measured height and weight, which increases the accuracy of calculated BMI percentile in children. Additionally, it is possible that there has been a change in dietary behaviors in young children between the time of the CSFII 1994–1996 and the NHANES 2001–2004. Finally, the more recent NHANES data collection included improved measures for assessing dietary intake that may have enhanced the accuracy of collection. Our study observed a small but meaningful difference of 0.11 kcal/g between the dietary ED of lean children and that of obese children. This would translate to a calculated difference of ~600 kcal/wk based on a mean intake of 690 g/d of food. In young children, this difference in energy intake would most certainly affect weight gain over time.

When examining the relationship between dietary ED and weight status by age group, different trends were seen. In children aged 4–8 y, there was an inverse association between dietary ED and BMI percentile (P = 0.047); children in the lowest ED quartile had significantly lower BMI than children in the highest quartile. In children 2–3 y old, this association was not observed. There are several possible explanations for this association with regard to the age of the children. Previous authors have demonstrated that weight status and age are significantly related and that obese children report lower energy intake than lean children (25). Another possible explanation may relate to the different methods used to calculate BMI percentile in very young children. In children older than 24 mo, standing height is assessed along with measured weight; in children up to 24 mo old, head circumference and recumbent length are assessed along with measured weight. In the present study, some of the 2-y-old children had recumbent length measured, while others had standing height measured. In children 4–8 y old, the relationship between dietary ED and weight status was also seen when examining the prevalence rates of obesity in each ED quartile such that the percentage of obese children increased steadily as ED quartiles increased. An important question is whether obese children are consuming larger portions of high-ED foods or simply not consuming enough low-ED foods during the day. By examining USDA-defined food components that are consumed in each category of dietary ED, potential factors that contributed to low- and high-ED diets could be examined. Several dietary behaviors were associated with dietary ED, including fruit and vegetable consumption, dietary fat, and consumption of added sugars.

One of the most notable differences in dietary behaviors between groups was observed in fruit and vegetable intake. In this sample of children aged 2–3 y, only children in the lowest ED category met the current USDA requirement for vegetable intake. Fruit intake yielded interesting results. When including 100% juice toward the total cups of fruit, all children exceeded the 1-cup recommendation; however, when juice was removed from the total number of fruit servings, only children in the lowest ED category met the recommendation. This indicates that most 2- to 3-y-old children are meeting the fruit requirement by drinking 100% juice. The high prevalence rate of juice consumption that was observed is similar to that found in the recent Feeding Infants and Toddlers study, where they reported that almost two-thirds of children consumed juice (26). Similar findings were observed in a recent study of a diverse sample of preschool children in Texas (27). There is an ongoing controversy about the benefits of juice consumption in preschool children; the proposed 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans describe the benefits of whole-fruit (as opposed to juice) consumption in children (12). Our results indicated that children consuming the highest ED diets (and subsequently had the highest BMI) were also consuming the most servings of juice. The relationship between juice consumption and body weight is controversial, because the evidence regarding the association has yielded mixed results. Some epidemiological evidence suggests that sweetened beverage consumption may be linked to obesity in both children and adults (28), whereas other studies have indicated that consumption of 100% fruit juice is not related to body weight in children and adolescents (29–31). Future studies are needed to investigate this relationship.

For children aged 4–8 y, similar patterns of intake were observed. When excluding juice and white potatoes, children in the lowest ED category were the only group that met the USDA recommendation for fruit and vegetable intake. Children in the other ED categories met the requirement for fruit intake only when juice was included and counted toward total intake. Though children in the lowest ED group consumed significantly more cups of vegetables than children in the highest ED group, they did not meet the requirement for 1.5 cups/d. Additionally, there were significant differences in the amount of added sugars in the diet between groups. Previous NHANES data suggest that almost 40% of daily energy intake in children comes from added sugars and solid fats (32). The presence of added sugars in the high-ED diet group may also play a role in the increased ED of the diet, which in turn may relate to weight status.

This study has several strengths. It is the first study to our knowledge to examine the relationship between dietary ED and body weight status in a large national dataset of children that included measured height and weight and included MyPyramid food group servings. Additionally, this study calculated dietary ED using multiple methods and it was determined that the calculation of food-only dietary ED provided the clearest picture of the results. There are a few limitations to this research. First, the data from this study is cross-sectional. Therefore, although a strong association was observed, we were not able to determine whether there is a causal relationship between dietary ED and weight status in children. Second, the data are based on a limited number of days of dietary recall. As with any self-reported data, there are inherent limitations to this method of dietary assessment. Our findings would be strengthened by repeating this analysis in a larger longitudinal data set. Finally, it is possible that the association of ED and body weight differs by racial or ethnic group. Earlier studies of ED in adults have found that dietary ED differs by race/ethnicity (33). The present study uses a subset of children aged 2–8 y; dividing this small age range into even smaller racial or ethnic subgroups would impair the reliability of the statistical procedures for this weighted survey data. Future studies may examine the influence of race or gender on the association between ED and weight status by looking at a larger age-range sample of children.

In conclusion, in a nationally representative sample of U.S. children between the ages of 2–3 and 4–8 y, the data demonstrated a positive association between dietary ED and weight status such that diets higher in ED were associated with greater prevalence of overweight and obesity. Children with low-ED diets reported consuming significantly more grams of food and significantly less energy than children with high-ED diets. Additionally, children with low-ED diets reportedly consumed significantly more servings of fruits and vegetables, significantly less energy from fat, and less added sugars than children with high-ED diets. Interventions that lower dietary ED by means of increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat consumption may be an effective strategy to reduce childhood obesity.

Acknowledgments

J.A.V., D.C.M., T.J.H., and B.J.R. designed the research; J.A.V. analyzed the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; D.C.M., T.J.H., and B.J.R. provided critical edits to the manuscript; and J.A.V. had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported in part by NIH DK082580 and DK059853.

Abbreviations used: CSFII, Continuing Survey of Food Intake for Individuals; ED, energy density; PIR, poverty:income ratio.

Literature Cited

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartline-Grafton HL, Rose D, Johnson CC, Rice JC, Webber LS. Energy density of foods, but not beverages, is positively associated with body mass index in adult women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:1411–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Kettel Khan L, Serdula MK, Seymour JD, Tohill BC, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density is associated with energy intake and weight status in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1362–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolls BJ, Leahy KE. Reductions in dietary energy density to moderate children's energy intake. : Dube L, Bechara A, Dagher A, Drewnowski A, Lebel J, James P, Yada RY, Obesity prevention: the role of brain and society on individual behavior. 1st ed London: Elsevier; 2010. p. 543–54 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Cheadle A, Christakis DA. Dietary energy density is associated with selected predictors of obesity in U.S. children. J Nutr. 2006;136:1318–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang TT, Howarth NC, Lin BH, Roberts SB, McCrory MA. Energy intake and meal portions: associations with BMI percentile in U.S. children. Obes Res. 2004;12:1875–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drewnowski A, Almiron-Roig E, Marmonier C, Lluch A. Dietary energy density and body weight: is there a relationship? Nutr Rev. 2004;62:403–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leahy KE, Birch LL, Fisher JO, Rolls BJ. Reductions in entree energy density increase children's vegetable intake and reduce energy intake. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:1559–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leahy KE, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Reducing the energy density of an entree decreases children's energy intake at lunch. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:41–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120 Suppl 4:S164–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003:160 [Google Scholar]

- 12.DGAC Report of the DGAC on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans; 2010. [cited 1 February 2011]. Available from: www.dietaryguidelines.gov [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drewnowski A, Specter SE. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:6–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1181–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monsivais P, Drewnowski A. Lower-energy-density diets are associated with higher monetary costs per kilocalorie and are consumed by women of higher socioeconomic status. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:814–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorito LM, Marini M, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Girls’ early sweetened carbonated beverage intake predicts different patterns of beverage and nutrient intake across childhood and adolescence. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:543–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHANES [cited 2011 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm

- 18.CDC Growth Chart SAS Program [cited 2011 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm

- 19. Growth Chart DatabaseCDC; 2010 [cited 2011 Jan 10]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/growthcarts.

- 20.Johnson L, Wilks DC, Lindroos AK, Jebb SA. Reflections from a systematic review of dietary energy density and weight gain: is the inclusion of drinks valid? Obes Rev. 2009;10:681–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stookey JD. Energy density, energy intake and weight status in a large free-living sample of Chinese adults: exploring the underlying roles of fat, protein, carbohydrate, fiber and water intakes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:349–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howarth NC, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Hankin JH, Kolonel LN. Dietary energy density is associated with overweight status among 5 ethnic groups in the multiethnic cohort study. J Nutr. 2006;136:2243–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Energy density of diets reported by American adults: association with food group intake, nutrient intake, and body weight. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29:950–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendoza JA, Watson K, Cullen KW. Change in dietary energy density after implementation of the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:434–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanctot JQ, Klesges RC, Stockton MB, Klesges LM. Prevalence and characteristics of energy underreporting in African-American girls. Obesity. 2008;16:1407–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox MK, Condon E, Briefel RR, Reidy KC, Deming DM. Food consumption patterns of young preschoolers: are they starting off on the right path? J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:S52–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans AE, Springer AE, Evans MH, Ranjit N, Hoelscher DM. A descriptive study of beverage consumption among an ethnically diverse sample of public school students in Texas. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29:387–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu FB, Malik VS. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Zanovec M, Fulgoni VL III. Diet quality is positively associated with 100% fruit juice consumption in children and adults in the United States: NHANES 2003–2006. Nutr J. 2011;10:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Kleinman R. Relationship between 100% juice consumption and nutrient intake and weight of adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24:231–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicklas TA, O'Neil CE, Kleinman R. Association between 100% juice consumption and nutrient intake and weight of children aged 2 to 11 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:557–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1477–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Seymour JD, Tohill BC, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density determined by eight calculation methods in a nationally representative United States population. J Nutr. 2005;135:273–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]