Abstract

This study attempted to assess the notion that a “good divorce” protects children from the potential negative consequences of marital dissolution. A cluster analysis of data on postdivorce parenting from 944 families resulted in three groups: cooperative coparenting, parallel parenting, and single parenting. Children in the cooperative coparenting (good divorce) cluster had the smallest number of behavior problems and the closest ties to their fathers. Nevertheless, children in this cluster did not score significantly better than other children on 10 additional outcomes. These findings provide only modest support for the good divorce hypothesis.

Keywords: coparenting, divorce, divorce interventions, parent-child relations

A substantial body of research shows that divorce is associated with behavioral, psychological, and academic problems among children. Research also indicates, however, that children’s reactions to divorce vary substantially. The quality of the family environment prior to separation, for example, is one predictor of how well children adjust to divorce. That is, children tend to show improvements in well-being when divorce removes them from high-conflict households and decrements in well-being when divorce removes them from low-conflict households (Booth & Amato, 2001; Jekeliek, 1998; Strohschein, 2005). Family relationships after divorce also appear to matter. As we describe later, research suggests that children’s adjustment is facilitated when nonresident and resident parents are positively involved in their children’s lives within the context of cooperative coparental relationships.

This research literature has led some scholars to embrace the notion of a “good divorce.” Ahrons (1994) described a good divorce as “one in which both the adults and children emerge as least as emotionally well as they were before the divorce” (p. 2). With respect to children, she stated,

In a good divorce, a family with children remains a family…The parents—as they did when they were married—continue to be responsible for the emotional, economic, and physical needs of their children. The basic foundation is that ex-spouses develop a parenting parentership, one that is sufficiently cooperative to permit the bonds of kinship—with and through their children—to continue (p. 3).

The belief that a good divorce can result in minimal distress—and even promote the development of children and adults—has pervaded the thinking of therapists, family courts, family scholars, and the general public.

To demonstrate the widespread influence of this notion, a GOOGLE search using the term “good divorce” produced over 400,000 hits (conducted on November 26, 2010). To examine the content of these websites, the authors randomly sampled 200 web pages from the first 680 listed. The majority of websites (60%) were not relevant to the current topic (e.g., How to find a good divorce lawyer.) The remaining websites (40%) contained articles from internet news services, magazines, or blogs that described or debated the notion of a good divorce; advice on how to have a good divorce; and reviews of relevant books dealing with this topic. The large number of GOOGLE hits indicates that the notion of a good divorce is widely discussed on the internet.

Although an intriguing possibility, the construct of a good divorce has rarely been examined directly. We use a nationally representative sample and cluster analysis to identify general patterns of postdivorce family life. We assume that a group of families with most of the characteristics of good divorces can be identified empirically. We then examine the extent to which children’s general adjustment and well-being vary between families with good divorces and those with other postdivorce parenting patterns.

Background

Postdivorce Parenting and Children’s Well-Being

The research literature indicates that divorce is associated with an increased risk of behavioral, psychological, and academic problems among children (Amato, 2000, 2010; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Kelly & Emery, 2003). Nevertheless, children’s reactions to divorce vary a great deal, with some children adjusting quickly and others showing long-term problems in adjustment. A number of studies have suggested that children’s adjustment following divorce depends on the quality of postdivorce family relationships. Most of this research has focused on (a) the quality of children’s relationships with nonresident parents and (b) the quality of coparental relationships.

Research is equivocal with respect to whether frequent contact with nonresident parents (usually fathers) benefits children. In an early study from the National Survey of Children, Furstenberg and Nord (1985) found that the frequency of nonresident parent-child contact was not related to measures of children’s well-being. A subsequent study based on the same data set (Furstenberg, Morgan, & Allison 1987) found that contact between children and nonresident parents consisted primarily of social rather than instrumental exchanges. That is, interaction frequently involved sharing a meal or playing together but rarely involved helping with homework or working on a school project together—a trend that may explain why contact does not necessarily translate into improvements in children’s development and well-being. Studies using other data sets also have failed to find significant associations between contact and child outcomes (Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1996; King, 1994; King & Heard 1999; Martinez & Forgatch, 2002).

Irrespective of the frequency of contact, however, children appear to benefit when they have close and supportive relationships with nonresident parents. Amato and Gilbreth’s (1999) meta-analysis of 63 studies documented significant associations between indicators of children’s well-being and the extent to which nonresident parents engaged in authoritative forms of behavior, such as talking with children about their problems, providing emotional support, helping with homework and everyday problems, setting rules, and monitoring children’s behavior. Studies conducted since then have continued to replicate this finding (Carlson, 2006; Harper & Fine, 2006; King & Sobolewski, 2006). Of course, nonresident parents who rarely see their children have few opportunities to engage in authoritative parenting. A moderate level of contact with nonresident parents, therefore, would appear to be a necessary but not a sufficient condition for enhancing children’s well-being.

Other research shows that the quality of the coparental relationship is associated with a range of child outcomes following union disruption. Children appear to benefit when parents communicate regularly, parents maintain similar rules in both households, and resident parents support the nonresident parent’s authority and parenting role. Correspondingly, children appear to suffer when parents argue frequently, maintain inconsistent rules, and attempt to undermine one another’s authority or relationships with children (Buchanan, Maccoby & Dornbusch, 1996; Harper & Fine, 2006; Sandler, Miles, Cookston, & Braver, 2008). Being pressured to take sides in parental disputes appears to be especially distressing for children (Buchanan, Maccoby & Dornbusch, 1996).

These two broad aspects of postdivorce parenting—parent-child relationships and coparental relationships—appear to be positively correlated. In a meta-analysis of relevant studies, Whiteside and Becker (2000) found that cooperative coparenting was associated with greater father-child visitation. Similarly, Sobolewski and King (2006) found that cooperative parenting was positively associated with the quality of the nonresident parent-child relationship as well as the frequency of visitation. In a study of unmarried mothers, Carlson, McLanahan, and Brooks-Gunn (2008) found that positive coparenting led to higher levels of father involvement over time. Other studies have shown that maternal satisfaction with the nonresident father-child relationship is associated with more frequent contact (King & Heard, 1999). In summary, previous research suggests that the quality of parenting and coparenting following divorce matters for children.

Typologies of Postdivorce Parenting

Although a large number of studies have examined postdivorce parenting, we know of only two studies that combined multiple dimensions of parenting to create typologies. Ahrons (1994) studied 98 divorced families in a Wisconsin county and used a cluster analysis of 13 interview items to create a typology of parenting styles. The items referred to how often former spouses argued; had stressful or tense conversations; accommodated changes in each other’s schedules; and had pleasant conversations with one another about their children, friends, and families. The analysis produced four groups of parents: “cooperative colleagues” (moderate interaction and high quality communication), “perfect pals” (high scores on interaction and communication), “angry associates” (infrequent interaction and moderate quality communication), and “fiery foes” (low scores on both dimensions). The first two groups represented good divorces. Ahrons also noted a fifth group of parents, “dissolved duos,” who had little or no communication, although she did not include this group in her analysis. This study was innovative because it drew attention to a subset of divorced parents that had not been the focus of previous research.

Maccoby and Mnookin (1992) studied 1,100 divorced families in two Northern California counties. Their analysis was restricted to families in which children spent at least some time with both parents during the school year, which represented between two thirds and three fourths of their full sample. A factor analysis of interview items yielded two factors: discord (e.g., frequent arguing, deliberate undermining of the other parent, multiple logistical problems regarding visitation) and cooperative communication (e.g., frequent communication about children, not avoiding contact with one another, and coordinating rules across households). To form groups, the authors split their sample at the median on each dimension. “Cooperative” parents scored high on communication and low on discord whereas “conflicted” parents scored low on communication and high on discord. “Parallel” parents scored low on both dimensions and dealt with conflict by avoiding one another. The fourth group was “mixed,” with high scores on both dimensions. (The fourth group was small and received little attention from the authors.)

Half of the parents in Ahrons’ study had positive relationships (38% cooperative colleagues and 12% perfect pals) compared with only one quarter (26%) of the parents in Maccoby and Mnookin’s sample. The difference may reflect variation in the period that parents divorced (the 1970s versus the 1980s), region of the country (Wisconsin versus California), or study methodology (cluster analysis versus factor analysis). Time since divorce also may be relevant. Maccoby and Mnookin (1992) found that high-conflict parenting decreased from 34% to 26% and parallel parenting increased from 29% to 41% between the first interview (about six months following divorce) and the third interview (about 3 ½ years after divorce). Consequently, estimates of the percentage of parents with positive coparental relationships may change with the length of time since union disruption.

In a follow-up of young adult children from the original sample, Ahrons (2004, 2007) and Ahrons and Tanner (2003) reported that youth had better relationships with their fathers and extended family members when their parents had good divorces. Buchanan, Maccoby, and Dornbusch (1996) also interviewed the adolescent children from their sample. Unfortunately, their study of adolescent outcomes did not use the parenting typology developed in the original report (Maccoby & Mnookin, 1992). Nevertheless, the authors reported that close relationships with nonresident parents and low levels of conflict between parents were associated with more positive adolescent outcomes.

Theoretical Considerations

The construct of a good divorce emphasizes the importance of multiple family relationships following divorce. As Ahrons (1994) noted, a family following divorce is still a family in the sense that mothers and fathers continue to be responsible for their children and need to cooperate to facilitate children’s well-being. This perspective appears to follow from a family systems perspective, in which the unit of analysis is not the individual but the larger family system. Family systems theory argues that a family consists of interconnected members, with each member influencing the others to maintain (or fail to maintain) a healthy system (Bowen, 1978; Minuchin, 1974). Influence involves patterns of communication and interaction, the extent to which family members are separate or connected, and adaptation to stress in the context of the entire family. In this sense, a well functioning postdivorce family is similar in many respects to a well functioning two-parent family: Mothers and fathers enact the parent role competently, children have close ties with both parents, and parents coordinate their activities to promote children’s development and well-being. Of course, divorced parents no longer have a romantic relationship or live together. But this difference does not mean that a postdivorce family cannot function in many respects like a healthy two-parent family. According to this perspective, if divorced parents emulate the behaviors and relationships of married parents in well-functioning families, then children will thrive.

An alternative perspective views divorce as a potentially stressful experience for children (Amato, 2000). According to stress theory, a large number of changes concentrated within a short time can have adverse effects on the mental and physical health of adults and children (Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005). Moreover, studies indicate that exposure to stressors during childhood predicts mental and physical health problems in adulthood (e.g., Clark, Caldwell, Power, & Stansfeld, 2010). Divorce brings about significant changes in most children’s lives, including the departure of one parent from the household, a decline in standard of living, moving to a new residence and neighborhood, giving up pets, changing schools, losing contact with friends and classmates, dealing with parents’ new romantic partners or spouses, living with step or half siblings, and adjusting to parents’ future union disruptions. Given that children thrive on stability (Cherlin, 2009), the cumulative effect of multiple changes concentrated within a short time increases children’s risk for a variety of problems. Even among children who do not develop clinically significant disorders, parental divorce can generate long-term feelings of unhappiness, confusion, and pain—despite parents’ best efforts to be supportive (Laumann-Billings & Emery, 2000; Marquardt, 2005). If mothers and fathers enact their parental roles competently and cooperate in raising their children, then some of the potentially negative effects of divorce can be avoided. But good parenting and coparenting only partly mitigate the full range of risk factors that often accompany divorce. According to this perspective, children who experience good divorces will benefit in some respects but will still experience many of the same problems as children in other types of postdivorce families.

The Current Study

Although our review is necessarily brief, it highlights some of the features that define a good divorce. Specifically, good divorces can be conceptualized as those in which children maintain close ties with both parents within the context of cooperative relationships between parents. Undoubtedly, some postdivorce families in the population fit this definition. Nevertheless, the number of prior studies is too small to determine how common these arrangements are. Moreover, the samples from prior studies were limited in several important respects. Ahrons’ (1994) sample was relatively small, came from a single county in Wisconsin, and was predominately White, middle class, and young. The Maccoby and Mnookin (1992) sample resided in two counties in the San Francisco Bay Area and was socioeconomically advantaged, contained fewer Black and more Hispanic families than expected, and over-represented families with joint physical custody. Set against this background, the current study has three goals.

First, we conduct a cluster analysis of families from Wave II of the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH) to create a typology of postdivorce parenting patterns. Although collected some years ago (1992–94), this data set contains an unusually rich set of questions dealing with relationships between nonresident parents and children and between nonresident and resident parents. Cluster analysis is primarily an exploratory method. Nevertheless, we anticipate a cluster that meets most of the criteria of a good divorce, as outlined earlier, as well as a cluster of nonresident parents who have little or no involvement with their children or former spouses. In addition, we anticipate clusters that correspond either to a high conflict pattern (at least moderate nonresident parent-child contact and a high level of conflict between former partners) or a parallel parenting pattern (at least moderate nonresident parent-child contact and little or no communication between former partners). The current analysis will determine how common these clusters were in the general population at the time of the survey. A second—primarily descriptive—goal of the current study is to examine how demographic and economic characteristics vary across parenting clusters.

Our third goal is to assess how measures of children’s adjustment and well-being vary across clusters. Prior literature suggests the “good divorce hypothesis,” that is, that children show the most positive profile of outcomes when their parents communicate frequently, conflict between parents is minimal, nonresident parents have frequent contact with children, and so on. An advantage of the NSFH Wave II dataset is that we are able to use resident parents’ reports of parenting and focal children’s reports of well-being, thus avoiding problems with shared method variance (or same-source bias). The current study examines a range of outcomes during adolescence in Wave II, including school grades, feelings about school, behavior problems, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and substance use. In addition, we utilize data from Wave III (collected in 2001–03) to assess offspring outcomes after they reach early adulthood. These outcomes include substance use, early sexual activity, the number of sexual partners, early union formation, and emotional closeness to mothers and fathers. Prior research has shown that all of these outcomes are related to parental divorce (Amato & Keith, 1991; Amato & Booth, 1997, Kelly & Emery, 2003). To our knowledge, the current study is the most extensive attempt to assess the implications of good divorces for children.

Although most studies have focused on divorce, we assume that this body of research is broadly applicable to families in which parents were never married to one another. That is, frequent contact with the nonresident parent in the context of a cooperative relationship between parents should benefit children, irrespective of whether parents were formally married. Despite our inclusion of unmarried parents in the current study, we retain the term “good divorce” because of its frequent use in scholarly literature and popular discourse. Readers should be aware that we use the term “divorce” to refer broadly to divorces, separations, and disruptions of nonmarital unions.

Method

Sample

The NSFH began in 1987–88 as a national probability sample of 13,017 households in the United States. The response rate for main respondents was 74%. In Wave I, parents in these households answered a series of questions about 3,806 randomly chosen focal children. In 1992–94 second interviews were conducted with 10,007 of the main (adult) respondents, and first interviews were conducted with 3,505 children. The third wave of data collection (in 2001–03) involved interviews with 4,123 children. (This total included some children not interviewed in Wave II.) Of the 3,055 parents interviewed in Wave II, 1,247 lived with focal a child who had a biological parent living in a different household. We restricted the sample to focal children between the ages of 7 and 19 in Wave II (mean = 12.4) and between the ages of 19 and 33 in Wave III (mean = 22.7). Finally, we restricted the analysis to 944 parent-child pairs in which we had data on at least one child outcome. (See Sweet and Bumpass, 2002, for methodological details on all three waves of data.) In this sample, 784 resident parents were previously married to the nonresident parent and 160 were never married to the nonresident parent.

Variables

Parenting types

We relied on a series of questions (asked of the resident parent) for the cluster analysis (described later). Although these questions do not saturate the good divorce construct as defined earlier, they cover the majority of criteria. Items that dealt with contact between the nonresident parent and the child included: “About how often did (child) talk on the telephone or receive a letter from (parent) during the last 12 months?” (1 = not at all, 6 = more than once a week), “During the last 12 months, how often did (child) see (parent) in person?” (1 = not at all, 6 = more than once a week), and “In the last 12 months, did (child) ever stay overnight with (parent)?” (1 = yes, 0 = no).

We relied on five items to assess the extent of coparental conflict: “How much conflict do you have about how (child) is raised? …how you spend money on (child)? …how (nonresident parent) spends money on (child)? …the time (nonresident parent) spends with child? …(nonresident parent’s) financial contribution to (child’s) support?” (0= none, 4 = a great deal). These items were equally weighted and combined to form a scale of coparental conflict (α = .73).

Additional items included, “During the last 12 months, how much help did you get from (nonresident parent) in raising (child)?” (0 = none, 4 = a great deal), “During the last 12 months, how much influence did (nonresident parent) have in making major decisions about such things as education, religion, and health care?” (0 = none, 4 = a great deal), “How often during the last 12 months did you talk about (child) with (nonresident parent)?” (0 = not at all, 4 = a great deal), “During the last 12 months, how much did (nonresident parent) interfere with the way you were raising (child)?” (0 = not at all, 4 = a great deal). Finally, resident parents were asked, “On a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is very unhappy and 10 is very happy, how happy are you with (nonresident parent) as a parent?”

Child well-being

Parents were asked a series of questions about problems that their children might have experienced, including repeating a grade, skipping school, being suspended or expelled from school, being asked to meet with a teacher or principal because of the child’s behavior, getting in trouble with the police, seeing a doctor or therapist because of an emotional or behavioral problem, and whether the child was particularly difficult to raise (0 = no, 1 = yes). The total number of problems served as the measure. Parents’ responses were available for 944 children.

Other measures of adjustment and well-being were obtained from the Wave II interviews with children (n = 455). Children were asked about their grades in school (1 = mostly F’s, 8 = mostly A’s) and how they felt about school (1 = hate it, 5 = love it). To assess self-esteem, children were asked four questions, including: “I feel that I’m a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others” and “I am able to do things as well as most other people” (1= strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree; α = .74). Overall satisfaction with life was based on the following item: “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is really bad and 10 is absolutely perfect, how would you say your life is going?” Finally, offspring were asked three questions about substance use: whether they had smoked a cigarette, consumed alcohol, or used marijuana within the last month (0 = no, 1 = yes). The sum of the items served as the scale score. The amount of missing data was no more than 5% for any outcome.

To assess long-term outcomes of postdivorce parenting styles, we used responses from 296 young adults interviewed in Wave III. We relied on a summary measure of substance use identical to the measure for Wave II adolescents. In addition, we included questions dealing with whether offspring had initiated sexual intercourse prior to the age of 16 (0 = no, 1 = yes), whether offspring had married or engaged in nonmarital cohabitation prior to the age of 20 (0 = no, 1 = yes), and the lifetime total number of sexual partners. In the NSFH, only about one-third (35%) of youth had sex prior to the age of 16, and only 13% had formed a cohabiting or marital union as teenagers. We included these questions because early initiation of sexual activity, early union formation, and having a large number of sexual partners are risk factors for nonmarital births as well as future union instability (Amato et al., 2008; Lichter, Turner, & Sassler, 2010; Sassler, Addo, & Hartmann, 2010). Finally, offspring were asked to rate the quality of their relationships with mothers and fathers on a 10-point scale, with 0 representing the worst possible relationship and 10 representing the best possible relationship. The amount of missing data was no more than 5% for any long-term outcome.

In a preliminary analysis involving simple mean comparisons, we found that children with divorced parents had lower levels of well-being than did children with continuously married parents on all 12 of the outcomes described above (p < .05). These findings suggest the appropriateness of using these outcomes in the main analysis.

RESULTS

Cluster Analysis

Because cases with missing data tend to differ from cases with complete data, listwise deletion tends to make a sample less representative of the population from which it was drawn. For this reason we used the expectation maximization (EM) procedure, implemented in SPSS, to impute missing data for the cluster analysis. The first step in this procedure involves a series of regression analyses to estimate missing values, with all variables in the dataset serving as predictors. The algorithm replaces missing values with the estimated values, and the regressions are run a second time. The algorithm then replaces the estimated values with updated estimates, and the procedure continues in an iterative fashion until changes in the estimated values are minimal. A limitation of the EM procedure is that it tends to underestimate the standard errors of imputed variables. Because cluster analysis does not involve significance testing, however, the EM procedure was appropriate for this purpose. (For a general discussion of these issues, see Allison, 2001).

We used the Two-Step Clustering procedure in SPSS (release 13.0) to cluster the 944 couples with dissolved unions. All variables were standardized (to have equal weights) prior to analysis. During the first step of this procedure, each case was either merged into a previously formed sub-cluster or started a new sub-cluster, depending on the mean and variance of each of the variables used in the categorization process. During the second step, SPSS used a hierarchical clustering method to cluster the sub-clusters. Both steps were based on a log-likelihood distance measure, with the distance between two clusters defined as the decrease in log-likelihood when the two clusters were combined into a single cluster. The algorithm also calculated the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for various clustering solutions and used this value to find an initial estimate of the optimal number of clusters. This estimate was then refined by finding the largest increase in the distance between cluster centers at each step. In the current analysis, the clustering procedure indicated that a three-cluster solution provided an optimal fit to the data.

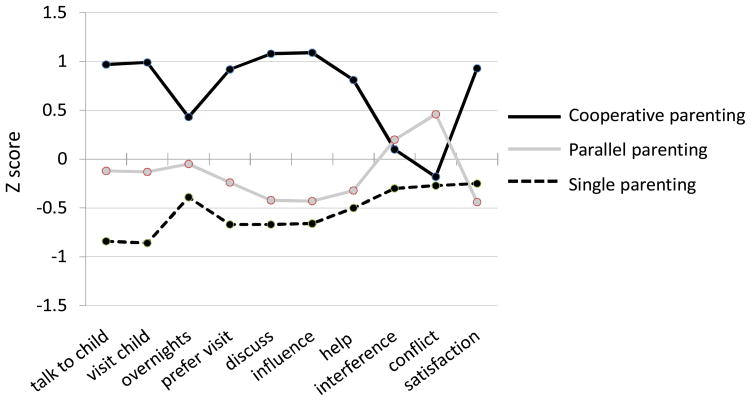

We labeled the three clusters “cooperative coparenting,” “parallel parenting,” and “single parenting.” Figure 1 shows the means of the parenting items for each cluster. To facilitate comparisons, differences between clusters were represented as Z scores. The figure shows that the differences between the three clusters were substantial for most indicators.

Figure 1.

Profile of Parenting Clusters

Resident parents in the high-contact, cooperative coparenting cluster reported the highest scores on children talking to, visiting, and staying overnight with nonresident parents. Resident parents in this cluster also had frequent discussions with nonresident parents, felt that nonresident parents had a substantial degree of influence on children, and agreed that nonresident parents helped to raise the children. These resident parents also reported little interference, only a modest level of conflict, and a high level of satisfaction with nonresident parents. This cluster, which displayed most of the characteristics of a good divorce, represented 29% of all families (weighted to be nationally representative).

In the parallel parenting cluster, nonresident parents had moderate levels of contact with children but low scores on discussions, influence, and helping to raise children. Resident parents reported little interference on the part of nonresident parents but a moderate degree of conflict and a low level of satisfaction. Nonresident parents in this cluster were involved with their children but communicated with resident parents infrequently and were perceived by resident parents as having a limited role in their children’s lives. This cluster represented 35% of all families in the sample (weighted). Although we refer to this cluster as “parallel parenting,” a more complete label would be “parallel parenting with some conflict.”

The third group represented 35% of families (weighted). We refer to the third cluster as “single parenting” because nonresident parents rarely saw their children, had little or no influence in their children’s lives, and had little or no communication with the resident parent. In this sense, resident parents in this group were true single parents. This cluster represented 36% of families (weighted).

We anticipated that clusters reflecting parallel parenting (high to moderate contact between nonresident parents and children with little or no communication between parents) and conflicted parenting (high to moderate contact between nonresident parents and children with a high level of conflict between parents) would emerge. The second cluster, however, appeared to incorporate elements of both groups. We suspect that a pure conflicted parenting group did not emerge from the analysis because this family pattern is (a) most likely to exist in the immediate aftermath of divorce and (b) highly unstable. That is, conflicted parenting is likely to change into either parallel parenting or single parenting with the passage of time (Maccoby & Mnookin, 1992).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the covariates separately for each of the three clusters. The previous marital status of parents (married versus never married) did not vary across clusters, which suggests that this variable had few implications for patterns of post union parenting. Resident parents in the cooperative coparenting cluster, however, were the least likely to be remarried (or married for the first time), which suggests the possibility that parental marriage interferes with the quality of postdivorce parenting (Amato & Sobolewski, 2004).

Table 1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Covariates by Parenting Cluster.

| Overall Sample | Cooperative Coparenting (CC) | Parallel Parenting (PP) | Single Parenting (SP) | Significant Differences (p < .05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents never married | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.23 | |

| Resident parent remarried | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.34 | CC < PP, SP |

| Resident parent is father | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.09 | CP > PP, SP |

| Resident parent education | 12.23 (2.04) | 12.68 (2.01) | 12.36 (1.96) | 11.75 (2.07) | CC, PP > SP |

| Income (1,000s) | 19.24 (16.32) | 24.59 (17.81) | 18.72 (15.53) | 15.33 (15.13) | CC > SP |

| Resident parent is White | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.55 | |

| Resident parent is Black | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.26 | |

| Resident parent is Hispanic | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.17 | |

| Resident parent is other | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Child age | 12.41 (3.52) | 12.24 (3.54) | 12.14 (3.49) | 12.78 (3.52) | |

| Child is son | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.47 | CC > SP |

| Months since separation | 81.04 (53.42) | 56.01 (49.69) | 74.55 (49.9) | 87.16 (57.67) | CC < PP < SP |

Note: Standard deviations (in parentheses) are not shown for binary or categorical variables. Means and proportions are weighted. All data were obtained from Wave II interviews. Unweighted sample sizes: cooperative coparenting (n = 254), parallel parenting (n = 328), single parenting (n = 362).

Nonresident parents were most likely to be mothers in the cooperative coparenting cluster (20%) and least likely to be mothers in the single parenting cluster (9%). This finding is consistent with research showing that nonresident mothers are more likely than nonresident fathers to maintain close relationships with their children following union disruption (Hawkins, Amato, & King, 2006). Correspondingly, parents had the highest levels of education and household income in the cooperative parenting cluster and the lowest levels in the single parenting cluster. (Note that income includes child support payments.) These findings are consistent with research showing that socioeconomic status is positively associated with nonresident parent-child contact and cooperative relationships between parents (Amato & Sobolewski, 2004).

Finally, the number of months since parental separation was lowest in the cooperative coparenting cluster and highest in the single parenting cluster. This finding suggests that some cooperative parents shifted into patterns of parallel or single parenting over time, as reported by Maccoby and Mnookin (1992). Consistent with this assumption, 38% of cases in the current analysis fell into the good divorce cluster when the analysis was restricted to divorces that occurred within the previous two years, whereas only 21% of cases fell into this cluster when the analysis was restricted to divorces that occurred at least five years ago.

Family Clusters and Children’s Well-Being

We regressed the 12 indicators of children’s adjustment and well-being on the family clusters and the control variables. In the first analysis, clusters 1 and 2 were represented by dummy variables and cluster 3 served as the omitted comparison group. In a second analysis, shifting the omitted group made it possible to assess all group differences for significance. We relied on full information maximum likelihood estimation to deal with missing data. This method adjusts covariance matrices for patterns of missingness and allows all nonmissing data to contribute to the results (Allison, 2001). Because behavior problems, substance use, and the number of sexual partners were count variables, we relied on Poisson regression for these outcomes. We relied on logistic regression for early sexual activity and early union formation because these were binary variables.

The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 2. For each outcome, the mean for cluster 3 (single parenting) was set at 0, and the means for clusters 1 (cooperative parenting) and 2 (parallel parenting) were based on standardized difference scores. In other words, the differences between family clusters in the table can be interpreted as effect sizes. These means were also adjusted for all covariates in Table 1. The table shows pairs of means that differed significantly at p < .05 (two-tailed).

Table 2.

Regression Coefficients (and Standard Errors) for Child Outcomes by Parenting Cluster

| Parenting Cluster

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperative Parenting (CP) | Parallel Parenting (PP) | Single Parenting (SP) | ||

| Adolescence | ||||

| School Grades | −.089 (.110) | −.290 (.098) | .000 | PP < SP |

| Like School | .072 (.120) | −.095 (.107) | .000 | |

| Behavior Problems | −.160 (.078) | .032 (.070) | .000 | CP < PP, SP |

| Self-Esteem | .088 (.118) | −.054 (.106) | .000 | |

| Substance Use | −.156 (.108) | .023 (.097) | .000 | |

| Life Going Well | .174 (.118) | .152 (.107) | .000 | |

| Young Adulthood | ||||

| Substance Use | .200 (.147) | .047 (.139) | .000 | |

| N sexual Partners | −.071 (.151) | .241 (.144) | .000 | PP > CP, SP |

| Early sex | .780 (.127) | .850 (.120) | 1.000 | |

| Early Unions | 1. 020 (.117) | 1.070 (.201) | 1.000 | |

| Close to Mother | .038 (.146) | −.189 (.135) | .000 | |

| Close to Father | .541 (.137) | .141 (.134) | .000 | CP > PP, SP |

Note: Table values (except for early sex and early unions) are standardized mean differences between children in the CP and PP clusters and children in the SP cluster (with standard errors in parenthesis). Table values for early sex and early unions are odds ratios. Value for children in the single parenting cluster are set to zero because this group served as the omitted reference category. Regression models include all covariates listed in Table 1. Unweighted samples sizes: cooperative coparenting (n = 254), parallel parenting (n = 328), single parenting (n = 362).

With respect to school grades, the mean for children in the parallel parenting cluster was .29 of a standard deviation lower than the mean for children in the single parenting cluster—a statistically significant difference (p < .05, two-tailed). Children in the cooperative coparenting cluster did not differ significantly from children in the other two groups. This result is not consistent with the hypothesis that children who experience a good divorce have the most positive outcomes. Contrary to the good divorce hypothesis, children in the single parenting cluster had the highest grades (although not significantly higher than children in the cooperative coparenting cluster).

With respect to behavior problems, children in the cooperative parenting cluster had the lowest mean score and were significantly different from children in the other two clusters (both p < .05). Specifically, children in the cooperative parenting cluster scored about one-fifth of a standard deviation below children in the parallel parenting cluster and about one-sixth of a standard deviation below children in the single parenting cluster. Although these effect sizes are modest, they were in the direction predicted by the good divorce hypothesis.

The results for the remaining four outcomes—self-esteem, substance use, liking school, and life satisfaction—revealed no significant differences between clusters. These results are not consistent with the good divorce hypothesis.

Table 2 also shows the results for older offspring in Wave III. Significant between-group differences emerged for two outcomes. First, children who experienced parallel parenting had a larger number of sexual partners than did children in the other two clusters. Children in the cooperative parenting group, however, did not differ from children in the single parenting group. Second, children in the cooperative parenting cluster had the closest relationships with their fathers. This particular finding is consistent with the hypothesis that children have the most positive outcomes when they experience a good divorce. Nevertheless, the other outcomes—substance use, early unions, early sexual activity, and closeness to mothers—did not differ significantly across clusters.

To examine whether these findings were affected by the inclusion of never married parents with disrupted unions in the sample, the analyses were done again with these individuals excluded. The results of these analyses did not substantively change the pattern of results reported in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

The cluster analysis revealed a group of families that met most of the criteria for a good divorce. Nonresident parents in these families saw their children frequently, had positive relationships with resident parents, and appeared to be part of a well functioning family system. Two of the child outcomes provided support for the good divorce hypothesis. Youth in the good divorce cluster exhibited fewer behavior problems (as reported by resident parents) and rated their relationships with fathers more positively than did youth in the other two parenting clusters. Adolescents in the good divorce cluster, however, were no better off than were adolescents in the single parenting cluster with respect to self-esteem, school grades, liking school, substance use, or life satisfaction. Correspondingly, young adults in the good divorce cluster were no better off than were young adults in the single parenting cluster with respect to substance use, early sexual activity, number of sexual partners, cohabiting or marrying as a teenager, and closeness to mothers. Overall, these results provide only partial support for the good divorce hypothesis.

Our findings appear to clash with prior studies suggesting that positive postdivorce family relationships have substantial benefits for children, as reviewed earlier. One explanation for this discrepancy involves methodological limitations of the current study. For example, the sample sizes were relatively small for some outcomes. If differences in child outcomes between clusters are small in the population, then the current study may not have had adequate statistical power to detect these differences. Although this explanation may contain some truth, it is somewhat unsatisfying in light of the strong claims that some have made about the benefits of good divorces for children. Another limitation of the current study is that we did not have the full range of variables to allow a more definitive identification of good divorces. Future data collection efforts that include larger sample sizes and appropriate interview items are needed to overcome these limitations.

Another concern is that the data from the current study come from the 1990s. It is possible that postdivorce families in the 2000s have better quality relationships than earlier cohorts of postdivorce families. Once again, this possibility can only be assessed with new data collection efforts. Nevertheless, claims about the benefits of good divorces emerged in the 1990s, so it is reasonable to assess these claims with data from the same decade.

Differences between the current studies and prior research also may reflect limitations of earlier studies. For example, most studies in this literature have relied on a single source for information for independent variables (postdivorce family relationships) and dependent variables (child outcomes). Common method variance tends to inflate the magnitude of associations and increase the risk of type I errors. For example, Buchanan, Maccoby, and Dornbusch (1996) found that adolescents’ reports of coparental conflict—but not parents’ reports of coparental conflict—were negatively and significantly associated with adolescents’ reports of well-being. With one exception, all of the independent and dependent variables in the current study were based on different sources (parents reporting on relationships and children reporting on outcomes), which minimizes this potential problem. These considerations suggest the possibility that common method variance accounts for many of the associations between postdivorce family relationships and child well-being reported in earlier studies.

Another possibility is that some earlier studies “cherry picked” the data. If the present study had focused only on parents’ reports of behavior problems and children’s reports of closeness to fathers, then the conclusion would be that good divorces have substantial benefits for children. But because we examined 12 diverse child outcomes, and because we reported null results along with significant results, the evidence in support of the good divorce hypothesis is weaker than anticipated.

In general, the well-know bias to publish only significant results may have led to an abundance of false positives in this research literature. During the last decade, medical scientists have become increasingly sensitive to this issue (see Ioannidis, 2005, for a discussion). In the current context, the notion that a good divorce is a panacea for children’s problems was compelling for many scholars in the 1990s. Many researchers and observers wanted it to be true. Under these circumstances, it would have been difficult for null results to find their way into the research literature. After an idea has gained widespread acceptance, however, it becomes easier for researchers to publish null findings, because results that contradict established ideas become “interesting.” These considerations suggest that the time may be appropriate to reconsider the notion of the good divorce.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Court-related policies

To minimize the level of conflict between divorcing parents, many courts have adopted non-adversarial methods of dispute resolution, such as mediation. Mediation, which is mandatory in many courts when parents cannot agree on issues such as custody and access, provides parents with the option of settling their disputes out of court (Douglas, 2006). A basic assumption is that through mediation, both partners have the opportunity to “win,” whereas in a contested case there is a clear “winner” and “loser.” In essence, the goal of mediation is to shift parents from an adversarial divorce to a good divorce. To the extent that mediation limits the level of ongoing acrimony between parents and increases children’s access to both parents following divorce, children should benefit.

In a series of studies, Emery and his colleagues produced some of the most compelling evidence in support of mediation (Emery, Matthews, & Kitzmann, 1994; Emery, Laumann-Billings, Waldron, Sbarra, & Dillon 2001). Parents who went through mediation were less likely to appear before a judge to settle their case, settled in less time, exhibited greater compliance with child support orders, and reported greater satisfaction with the process twelve years later. This research also found that mediation resulted in more communication between parents, more nonresident parent-child contact, and greater involvement of the nonresident parent in children’s lives. A twelve-year follow-up, however, did not reveal differences in the psychological well-being of children (Emery, Sbarra, & Grover, 2005).

Divorce education classes for parents are currently mandated by courts to varying degrees in most states (Blaisure & Geasler, 2006). These programs teach divorcing couples about the benefits for children of having two involved parents, engaging in cooperative coparenting, and minimizing children’s exposure to interparental conflict (Douglas, 2006). As with mediation, the goal of divorce education is to assist parents in having a good divorce. Evaluation studies indicate that most parents find these classes to be useful, even when attendance is compulsory. Many parents also report declines in conflict and improvements in communication and cooperation (Pollet & Lombreglia, 2008). Moreover, parents who participate in these programs report better child adjustment than do other parents (Fackrell, Hawkins, & Kay, in press). Nevertheless, these findings should be treated cautiously. In most studies, parents are not assigned randomly to treatment and control groups, and studies that look at children’s adjustment are based entirely on parents’ reports and, hence, may be contaminated by same-source bias.

Although mediation and divorce education classes are useful, helping parents to have good divorces may be insufficient to buffer children from the full range of risk factors that often accompany marital dissolution. In addition to teaching mothers and fathers about effective parenting styles, parents also need to learn strategies for reducing children’s exposure to a variety of potential stressors, such as a decline in standard of living, changing residences, and the integration of parents’ new partners into children’s lives. Expanding the content of parenting classes to address these issues may be useful direction. In addition, court-connected interventions for children (rather than parents) could be more widely available (Geelhoed, Blaisure, & Geasler, 2001). In contrast to interventions for parents, programs for children—many of which are set in schools—have been carefully evaluated and appear to benefit children (Kalter, & Schreier, 1993; Lee, Picard, & Blain, 1994; Pedro-Carroll, 2010). These programs (a) provide children with cognitive and social skills that help them navigate the transition to postdivorce family life, and (b) increase children’s social support by connecting them with peers in similar situations. Court referrals to these child-focused interventions are likely to be a useful supplement to parent-focused interventions.

Marital Therapy

A national survey revealed that 60% of marriage therapists are neutral about marriage and divorce (Wall, Browning, & James, 1999). These individuals believe that their most important role is to help their clients be happy, irrespective of whether their clients’ marriages improve or end in disruption. In contrast, only about one third of marriage therapists believe that their most important role is to improve and save the marriages of their clients. As Doherty (2002) argued, a “neutral” stance toward marriage and divorce often involves implicit value judgments. When spouses in therapy reveal that they are thinking seriously about divorce, many therapists assume that these marriages cannot be salvaged and, hence, conclude that their best option is help these couples achieve good divorces. The findings of the current study suggest that this strategy is limited, at least for couples with children. Creating a positive postdivorce family environment—although worthwhile—is no guarantee that children will be unharmed by marital dissolution. For couples not yet fully committed to ending their marriages, focusing more strongly on rebuilding and improving the marital relationship makes a great deal of sense, especially when serious problems such as domestic violence are not present (Doherty, 2002).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the notion of a good divorce has captured the attention of the general public, the media, marriage therapists, and the family court system. Interventions that help parents maintain strong relationships with their children and cooperate in the postdivorce years are undoubtedly of value. Nevertheless, these interventions may be insufficient to counter the full range of problems associated with divorce. Although additional research needs to be conducted, the current study suggests that a good divorce is not a panacea for improving children’s well-being in postdivorce families. Not all children with divorced parents experience long-term problems. But people’s willingness to accept the good divorce hypothesis is reason for concern if some parents are lulled into believing that their children are adequately protected from all of the potential risks of union disruption.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work benefited from core support to the Population Research Institute at Pennsylvania State University under NIH Grant R24 HD41025 as well as a grant for interdisciplinary training in demography from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; T-32HD007514, Gordon DeJong, principal investigator).

References

- Ahrons C. The Good Divorce: Keeping your family together when your marriage comes apart. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrons CR. Family ties after divorce: Long-term implications for children. Family Process. 2007;46:53–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrons C. We’re still family: What grown children have to say about their parents’ divorce. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrons CR, Tanner JL. Adult children and their fathers: Relationship changes 20 years after parental divorce. Family Relations. 2003;52:340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences (07–136) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. Missing Data. [Google Scholar]

- Amato P. The Consequences of Divorce for Adults and Children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1269–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:650–666. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental Divorce and Adult Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53(1):43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Booth A. A Generation at Risk: Growing up in an Era of Family Upheaval. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Gilbreth J. Nonresident fathers and children’s well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:557–573. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Sobolewski J. The effects of divorce on fathers and children: Nonresidential fathers and stepfathers. In: Lamb M, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 341–367. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Landale NS, Havasevich-Brooks TC, Booth A, Eggebeen DJ, Schoen R, McHale SM. Precursors of Young Women’s Family Formation Pathways. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1271–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaisure KA, Geasler MJ. Educational interventions for separating and divorcing parents and their children. In: Fine M, Harvey J, editors. Handbook of divorce and relationship dissolution. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 575–602. [Google Scholar]

- Booth Alan, Amato PR. Parental predivorce relations and offspring postdivorce well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. Family therapy in clinical practice. New York: Jason Aronson; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CM, Maccoby EE, Dornbusch SM. Adolescents after Divorce. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ. Family structure, father involvement, and adolescent behavioral outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, McLanahan SS, Brooks-Gunn J. Coparenting and Nonresident Fathers’ Involvement with Young Children after a Nonmarital Birth. Demography. 2008;45(2):461–488. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld SA. Does the influence of childhood adversity on psychopathology persist across the lifecourse? A 45-year prospective epidemiologic study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. New York: Alfred A. Knopt; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ. How therapists harm marriages and what we can do about it. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy. 2002;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas EM. Mending broken families: Social policies for divorced families. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Matthews SG, Kitzmann KM. Child custody mediation and litigation: parents’ satisfaction and functioning one year after settlement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:124–29. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Laumann-Billings L, Waldron M, Sbarra DA, Dillon P. Child custody mediation and litigation: Custody, contact, and co-parenting 12 years after initial dispute resolution. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:323–332. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Sbarra D, Grover T. Divorce Mediation: Research and Reflections. Family Court Review. 2005;43(1):22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fackrell TA, Hawkins AJ, Kay NM. How effective are court-affiliated divorcing parents education programs? Family Court Review (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Nord CW. Parenting Apart: Patterns of Childrearing after Marital Disruption. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1985;47(4):893–904. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Morgan SP, Allison PD. Paternal Participation and Children’s Well-being after Marital Dissolution. American Sociological Review. 1987;52(5):695–701. [Google Scholar]

- Geelhoed RJ, Blaisure KR, Geasler MJ. Status of court-connected programs for children whose parents are separating or divorcing. Family Court Review. 2001;39:393–4004. [Google Scholar]

- Harper SE, Fine MA. The effects of involved nonresidential fathers’ distress, parenting behaviors, inter-parental conflict, and the quality of father-child relationships on children’s well-being. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers. 2006;4(3):286–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins Daniel, Amato Paul R, King Valarie. Parent-Adolescent Involvement: The Relative Influence of Parent Gender and Residence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Kelly J. For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. NY: Norton; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JPA. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2(8):e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekielek SM. Parental conflict, marital disruption and children=s emotional well-being. Social Forces. 1998;76:905–935. [Google Scholar]

- Kalter N, Schreier S. School-based support groups for children of divorce. Special Services in the Schools. 1993;8:39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Emery RE. Children’s Adjustment Following Divorce: Risk and Resilience Perspectives. Family Relations. 2003;52(4):352–362. [Google Scholar]

- King V. Nonresident father involvement and child well-being: Can dads make a difference? Journal of Family Issues. 1994;15:78–96. [Google Scholar]

- King V, Heard HE. Nonresident father visitation, parental conflict, and mother’s satisfaction: What’s best for child well-being? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(2):385–396. [Google Scholar]

- King V, Sobolewski JM. Nonresident fathers’ contributions to adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:537–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann-Billings L, Emery RE. Distress among young adults from divorced families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:671–687. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Picard M, Blain MD. A methodological and substantive review of intervention outcome studies for families undergoing divorce. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Turner RN, Sassler S. National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation. Social Science Research. 2010;39:754–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Mnookin RH. Dividing the Child: Social and legal dilemmas of custody. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt E. Between two worlds: The inner lives of children of divorce. New York: Crown Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Forgatch MS. Adjusting to family change: Linking family structure transitions with parenting and boys’ adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:107–117. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin Salvador. Families and Family Therapy. Oxford: Harvard; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro-Carroll J. Putting children first: Proven strategies for helping children thrive through divorce. New York: Avery; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pollet SL, Lombreglia M. A Nationwide Survey of Mandatory Parent Education. Family Court Review. 2008;46(2):375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Miles J, Cookston J, Braver S. Effects of father and mother parenting on children’s mental health in high- and low-conflict divorces. Family Court Review. 2008;46:282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, Addo F, Hartmann E. The tempo of relationship progression among low-income couples. Social Science Research. 2010;39:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewski JM, King V. The importance of the coparental relationship for nonresident fathers’ ties to children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;67(5):1196–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein L. Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1286–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet JA, Bumpass LL. The National Survey of Families and Households -Waves 1, 2, and 3: Data description and documentation. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2002. ( http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/nsfh/home.htm) [Google Scholar]

- Wall JN, Browning DS, James S. The ethics of relationality: The moral views of therapists engaged in marital and family therapy. Family Relations. 1999;48:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, El ghormil, Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: An approach for molecular epidemiology studies. Jounal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96:434–442. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside MF, Becker BJ. Parental factors and young child’s postdivorce adjustment: A meta-analysis with implications for parenting arrangements. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:5–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]