Abstract

Many jurisdictions have considered relaxing Sunday alcohol sales restrictions, yet such restrictions' effects on public health remain poorly understood. This paper analyzes the effects of legalization of Sunday packaged liquor sales on crime, focusing on the phased introduction of such sales in Virginia beginning in 2004. Differences-in-differences and triple-differences estimates indicate the liberalization increased minor crime by 5% and alcohol-involved serious crime by 10%. The law change did not affect domestic crime or induce significant geographic or inter-temporal crime displacement. The costs of this additional crime are comparable to the state's revenues from increased liquor sales.

Keywords: alcohol, crime

I. Introduction

Miller et al. (2006) estimate the annual cost of crimes attributable to alcohol at $84 billion, while Greenfeld (1998) estimates that nationally more than 3 million violent crimes are committed each year in which the offender is likely to have used alcohol, and alcohol is a factor in two-thirds of all domestic violence cases. Policymakers have implemented a variety of strategies aimed at managing the negative social consequences of unhealthy alcohol consumption, including crime. Among other restrictions on the location and timing of alcohol sales, limits on the sale of liquor on Sundays remain common in the United States. As of 2010, fourteen states and numerous individual localities had statues limiting Sunday liquor sales. However, there is a growing movement to repeal such laws, with six states enacting repeals of Sunday liquor laws since 2002.

Despite the fact that numerous state legislatures have recently re-examined and modified laws governing the sale of alcoholic beverages on Sunday, empirical evidence regarding the public health effects of these laws remains relatively limited. A handful of studies have examined whether repeals of Sunday alcohol laws impact traffic fatalities (McMillan and Lapham 2006, Lovenheim and Steefel 2010), finding mixed results. To date no studies have examined whether Sunday alcohol restrictions affect crime in the United States.

This paper uses detailed crime incident data surrounding a period in which Virginia relaxed Sunday sales restrictions in certain jurisdictions to estimate the causal effect of laws restricting Sunday packaged liquor purchases on crime. Employing a difference-in-differences and triple-differences methodology to control for confounding factors affecting crime rates, I demonstrate that the Sunday sales repeal led to a 5% increase in lower-level property and public order crime and an 10% percent increase in alcohol-involved serious crime. As expected, these effects are concentrated among crime types and locations that are most plausibly affected by alcohol policy, and the results are robust to the use of alternative samples and statistical specifications. A simple cost analysis suggests that the monetized social cost of the additional crime generated by the repeal roughly equals the revenue generated for the state from additional liquor sales.

Section 2 of the paper selectively reviews prior work examining links between alcohol availability and crime. Existing research provides ambiguous guidance regarding the expected effect of Sunday sales restrictions on crime. Section 3 describes the policy experiment that occurred in Virginia and outlines the data used in the analysis. Section 4 presents the differences-in-differences and triple-differences approaches used to measure the effects of the law change. Section 5 reports the primary results, including a series of robustness checks. Section 6 presents the cost analysis, and Section 7 concludes.

II. Why Might Sunday Liquor Laws Impact Crime?

There is a robust body of evidence linking general availability of alcohol to crime. This literature would seem to suggest that policies that restrict alcohol availability such as Sunday sales restrictions might lower crime. At the same time, the applicability of existing research to Sunday liquor laws remains unclear given that these laws likely have different effects on alcohol consumption and associated routine activities than other commonly used proxies for availability, such as taxes or outlet density.

Numerous individual-level studies demonstrate a correlation between measures of alcohol availability and crime.1 Saffer (2001) demonstrates that self-reported arrest and property crime are lower in states with higher alcohol taxes. Using data from the Monitoring the Future Study, Markowitz (2001) documents a similar relationship between alcohol and violence. Using an innovative regression discontinuity design, Carpenter and Dobkin (2008) show that both alcohol consumption and violent arrests increase substantially just after individuals attain the legal drinking age.

Research has also demonstrated a relationship between alcohol availability and crime on a community and state level. Using UCR data from 1979–1987, Cook and Moore (1993) demonstrate that state-level alcohol consumption is associated with increases in assaults, rape, and burglary. They also demonstrate that increased alcohol taxes are associated with decreases in rape and robbery. Sloan et al. (1994) and Berman et al. (2000) show an inverse relation between jurisdictional alcohol regulation and homicide. Speer et al. (1998) and Scribner et al. (1995) perform a tract-level analysis of alcohol outlets in individual cities and demonstrate that homicides are more likely to occur in tracts with a high density of licensed alcohol providers. Ray et al. (2008) demonstrate a dose-response effect, showing that hospitalizations for assault are increasing in the volume of alcohol sold in neighborhood outlets.

Beyond general violent crime, there is also evidence that alcohol availability affects family violence. Using self-reported violence data from the 1985–1987 panel of the National Family Violence Survey, Markowitz (2000) demonstrates that female-directed domestic violence is lower in areas with high alcohol prices, her proxy for availability. Markowitz and Grossman (2000) similarly demonstrate a negative relationship between alcohol prices and child abuse.

Although the correlational evidence suggests expanded availability might increase crime, the role of many specific alcohol control measures remain poorly understood. Moreover, even for policies that have been more extensively studied, such as zoning laws, there exist few credible estimates of causal policy effects.2 In the specific case of Sunday sales restrictions, the theoretical links between the policy and crime are particularly murky.

Several lines of reasoning suggest the repeal of a selective liquor restriction would be unlikely to affect crime. Perhaps the strongest argument against a significant effect is the fact that packaged liquor purchased on Sundays in highly substitutable with other forms of alcohol. Liquor is readily storable, so individuals wishing to consume packaged liquor on Sundays can easily purchase it on other days of the week and then consume during periods when sales are restricted. The sales ban affects packaged liquor but does not affect packaged beverages with lower alcohol content, such as beer, nor does it affect liquor sold by the glass in restaurants. These products are likely close substitutes for packaged liquor. Finally, residents near Maryland and Kentucky can also cross the border and purchased packaged liquor on Sundays in selected jurisdictions in those states. The seemingly high degree of intertemporal, geographic, and product substitutability for packaged liquor purchased on Sundays argues against a large effect of the repeal of the ban on consumption or associated harms.

However, some existing scholarly work does offer evidence suggesting the repeal of these laws might have a less benign effect. Olsson and Wikström (1982) argue that the temporary closure of state-run monopoly liquor stores in Sweden on Saturdays during a three-month period appreciably reduced public order crime, domestic disturbances, and assaults.3 Stehr (2007) presents evidence that overall alcohol sales rise in states that repeal Sunday sales bans, and Carpenter and Eisenberg (2009) examine a repeal of a ban on off-premises alcohol sales in Ontario, Canada and find that the repeal did not increase overall alcohol consumption but did increase Sunday consumption.4 Grunewald et al. (2006) demonstrate that the density of off-premises alcohol outlets is more strongly correlated with crime patterns than restaurants or bars. Although this evidence is only correlational in nature, it suggests the possibility that displacement of alcohol from consumption in bars or restaurants to consumption in other locations might affect crime even absent an increase in overall consumption. More broadly, there is a growing literature indicating that situational factors, including those associated with alcohol use, can have important short-run effects on crime (Jacob and Lefgren 2003; Jacob, Lefgren, and Moretti 2007; Dahl and DellaVigna 2009; Rees and Schnepel 2009; Card and Dahl 2010). Thus, existing theory and empirical work do not provide a strong basis for predicting the likely effects of repealing a Sunday liquor ban on crime.

III. Institutional Background and Data

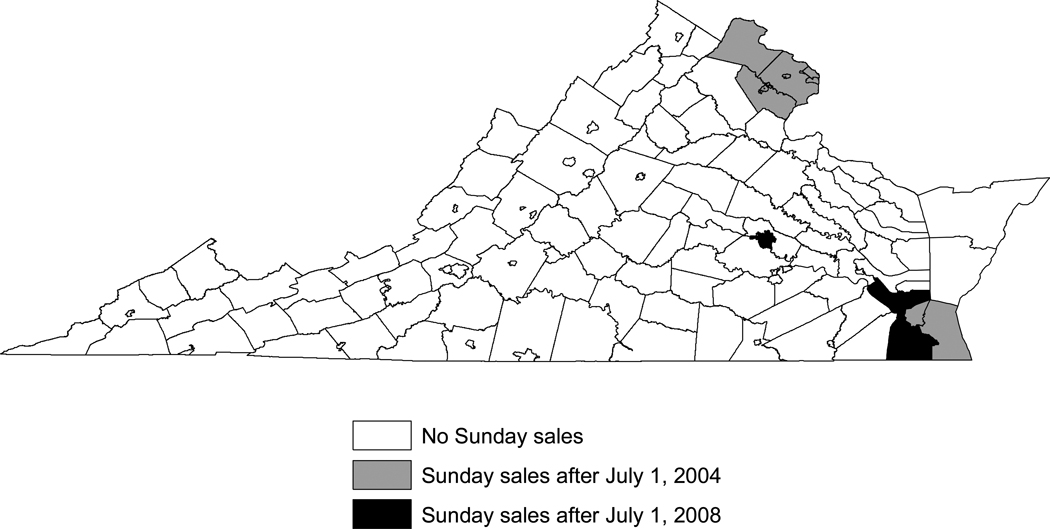

To empirically resolve this question, I exploit a series of laws that progressively expanded the jurisdictions in which packaged liquor could be purchased on Sundays in Virginia. As in many states, alcohol licensing and sales are regulated in Virginia by a state Department of Alcohol Beverage Control (VABC). Liquor by-the-glass can be purchased in restaurants on weekdays and Sundays in most jurisdictions within the state.5 Although beer and wine are available in grocery stores, container sales of beverages exceeding 14% alcohol by volume are restricted to state-run ABC stores. Prior to 2004, all Virginia ABC stores were closed on Sundays pursuant to state law. In April 2004, Virginia passed HB 1314, which amended its alcoholic beverage control law to permit ABC stores in 11 of the state’s 134 independent cities and counties to open on Sundays.6 Beginning in July 2004, 50 ABC outlets in these areas began selling alcohol from 1–6 p.m. each Sunday. Citing the success of its 2004 approval of Sunday alcohol sales, in July 2008 the Virginia General Assembly expanded Sunday sales to an additional 36 stores in Portsmouth, Hampton, Newport News, Richmond and Chesapeake. Appendix Figure 1 displays a map of Virginia with the affected jurisdictions highlighted.

Appendix Figure 1.

Jurisdictions with Changes in Sunday Liquor Availability

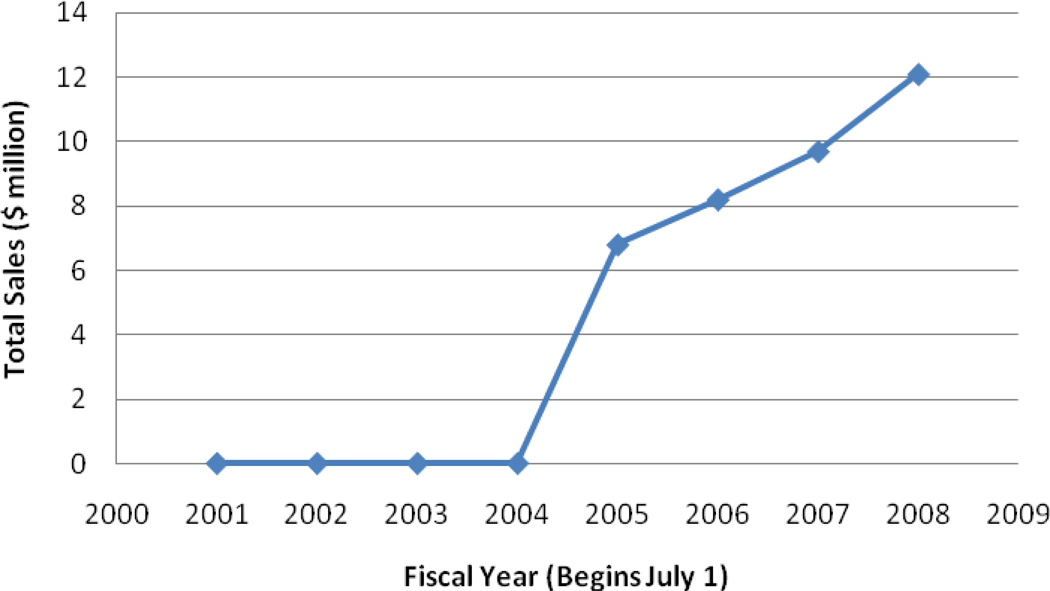

Appendix Figure 2 plots revenue from Sunday container liquor sales in Virginia by fiscal year. Sales were zero prior to July 2004 because Sunday liquor sales were illegal. Over time, Sunday liquor purchases have increased steadily, generating revenue of over $12 million by FY2008. Based upon aggregate sales and purchase data, this $12 million in revenue translates to roughly 170,000 gallons of liquor sold on Sundays in FY2008, or roughly 1 gallon for every 10 adult residents in the jurisdictions permitting alcohol sales.

Appendix Figure 2.

Sunday Sales at VABC Liquor Stores

It is worth noting there are numerous ways to restrict the availability of alcohol on Sundays, including limits on beer and wine sales and limits on sales in bars and restaurants. The law change examined in this paper is one specific type of restriction focused on a particular class of beverages (liquor) and a particular type of sale (off-premise packaged sales). Thus the degree to which the findings here generalize to other Sunday alcohol control policies remains uncertain. At the same time, the particular type of restriction examined here is commonplace, affecting residents of fourteen other states. Moreover, several of the states that have repealed Sunday sales laws or are considering repeals have alcohol control policies similar to those in place prior to Virginia’s repeal.

To analyze the impacts of the law change on crime, I draw from the public-use files for the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). Designed as a replacement for the FBI's Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program, NIBRS collects detailed information regarding each crime reported to participating local police agencies. Although NIBRS has not yet been implemented nationwide, in 2001–2008, the years of the analysis, all major state and local police agencies in Virginia were NIBRS participants.7

NIBRS divides crimes into two major categories, Group A and Group B crimes. Group A crimes are more serious crimes, including the FBI Part I Index crimes8 along with other crimes such as simple assault, fraud, drug offenses, and weapons law violations. For each Group A crime, I observe a rich set of information drawn from each crime report, including the date and time of the incident, the type of offense, the responding police agency, and the type of location at which the crime was occurred. Gender, race, and age of the offender are recorded when observed by the victim. The data also include information about suspected alcohol, drug, and weapon involvement with the offense; the demographics of the victim (where applicable); the nature of the victim/offender relationship; and property damaged or stolen. If an arrest is made, information about the date of the arrest and the demographic characteristics of the arrestee are included. The data thus allow me to identify crimes that occurred on Sundays, compare crime rates across jurisdictions, observe domestic incidents, and separately analyze violent crimes.9

Group B crimes are lower-level crimes that always involve an arrest. Included in this category of crimes are DUI, public drunkenness, disorderly conduct, trespassing, and several other public order offenses. Although they include basic information such as the date of the crime and arresting agency, NIBRS records for Group B crimes are less comprehensive than Group A records, most notably omitting the hour of the crime and the separate indicator for alcohol/drug involvement. These records do include demographic information about the arrestee.

Table 1 summarizes the NIBRS data, reporting the average number of daily crimes per police jurisdiction across several crime categories. As is apparent from the crime and population counts, the fifteen jurisdictions that have been affected by the repeal are larger than average. For our primary specifications, we focus attention on a control group consisting of other urban jurisdictions in the state10; the final column of the table suggests that non-urban jurisdictions have crime levels an order of magnitude below the treated jurisdictions, and thus these localities may constitute a less apt comparison group.11 Table 1 indicates that Group A crime accounts for the bulk of reported crime in the state, with Group A property crime accounting for roughly half of all crime. A minority of Group A crimes involve alcohol or domestic interactions. In all four sets of jurisdictions, a less than proportionate share of crime occurs on Sunday. Among Group B crimes, DUI and drunkenness are relatively prevalent, but it is also notable that a significant fraction of Group B crimes are not specifically categorized.

Table 1.

Summary Daily Crime Counts for Jurisdictions in Virginia, 2001–2008

| Original (2004) Repeal Jurisdictions |

Later (2008) Repeal Jurisdictions |

Other Urban Jurisdictions |

Other Non- Urban Jurisdictions |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of jurisdictions | 10 | 5 | 20 | 99 |

| Share of crime occurring on Sunday | 12.9% | 11.6% | 12.0% | 12.5% |

| Average daily total crimes | 57.05 | 67.40 | 22.69 | 5.47 |

| Group A crimes | ||||

| Total | 42.98 | 53.60 | 16.16 | 3.75 |

| Violent | 8.57 | 13.30 | 3.45 | 0.81 |

| Property | 30.68 | 34.22 | 10.96 | 2.46 |

| Public order | 3.72 | 6.08 | 1.74 | 0.47 |

| Alcohol-involved | 2.73 | 3.99 | 1.14 | 0.31 |

| Domestic | 1.59 | 1.59 | 0.57 | 0.16 |

| Group B crimes | ||||

| Total | 14.07 | 13.80 | 6.54 | 1.72 |

| Disorderly conduct | 0.65 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.04 |

| DUI | 2.13 | 1.10 | 0.69 | 0.29 |

| Drunkenness | 2.41 | 1.79 | 0.87 | 0.25 |

| Liquor law violation | 0.98 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.08 |

| Unclassified (Other) | 6.42 | 7.62 | 3.15 | 0.86 |

| Average population | 245,636 | 163,945 | 56,312 | 26,927 |

| Average land area (sq. mi.) | 161 | 105 | 56 | 366 |

Note: Reported crime counts represent the average daily number of crimes of each type per locality. Data for Fairfax City has been excluded due to inconsistent NIBRS reporting during the sample period.

IV. Empirical Approach

I use differences-in-differences (DD) and triple-differences (DDD) comparisons to estimate the effect of legalizing Sunday packaged liquor sales on crime. A key empirical challenge in estimating the effect of the law is accounting for external factors, such as law enforcement practices, that may be correlated with the passage of the law and independently affect crime rates but which may be unobservable to the researcher. The differences-in-differences estimates account for such factors by using crimes on other days of the week as a control group for crimes on Sundays and crime patterns in the pre-reform period as controls for crime patterns following the reform. This approach differences away the effects of macroeconomic trends as well as any confounding factors that are shared equally across days of the week. For example, if the law change coincided with an unobserved increase in law enforcement personnel, because these personnel would likely affect enforcement on both Sundays and other days of the week, their influence would not bias the difference-in-difference estimates.

The differences-in-differences estimation approach can be implemented in a regression framework in which the unit of observation is a day within a jurisdiction.12 Let yijt denote the number of crimes committed on date t in locality j where i indexes the day of the week. The primary explanatory variable is CanSellijt, which is an indicator variable equal to 1 on Sundays if Sunday liquor sales are permitted in jurisdiction j in time t and 0 otherwise. Let Di denote a set of indicator variables for each day of the week, Lj jurisdiction indicators, Mt time indicators13, and Xjt time-varying control covariates. In the regression:

| (1) |

The coefficient β measures the effect of legalizing Sunday liquor sales on crime. Because crime varies seasonally and across days of the week, we control for these factors using Di and Mt. Li controls for time-invariant factors specific to a jurisdiction that might affect crime, such as geography. Xjt includes indicators for major holidays and, in some specifications, jurisdiction specific time trends. I separately consider different types of crimes such as violent crime, property crime, alcohol-involved crime, and domestic violence as outcomes. Given the count nature of the data, I estimate (1) using Poisson regression.14

Although the differences-in-differences approach provides a stronger research design than simple pre-post comparisons, other unobserved factors affecting time use on Sundays might possibly still explain changes in relative crime rates over time.15 The fact that liquor sales restrictions were lifted in only a limited set of jurisdictions in Virginia provides an additional source of variation that we can exploit. In particular, in addition to conducting differences-indifferences comparisons as described above, we can include an additional difference comparing affected and unaffected jurisdictions in a triple-differences framework. This can be achieved estimating regressions of the form:

| (2) |

where the notation is as in equation (1) and, for example, Di · Lj denotes interactions between each jurisdiction and the day of the week. A notable feature of these regressions is that they include a full set of interactions between location and day of week, day of week and time, and location and pre/post implementation status. These interaction terms render the triple-differences analysis robust to unobserved changes in daily activity patterns that are specific to particular time periods or particular jurisdictions. For example, if additional TV advertisements for alcoholic beverages were aired on Sundays after July 2004, the differences-in-differences analysis might confound the effects of these advertisements with the effects of the law change. However, provided that the unobserved confounding factors occurred in both treated and untreated jurisdictions (which is likely true for TV advertising), the triple-differences approach removes the confounders.

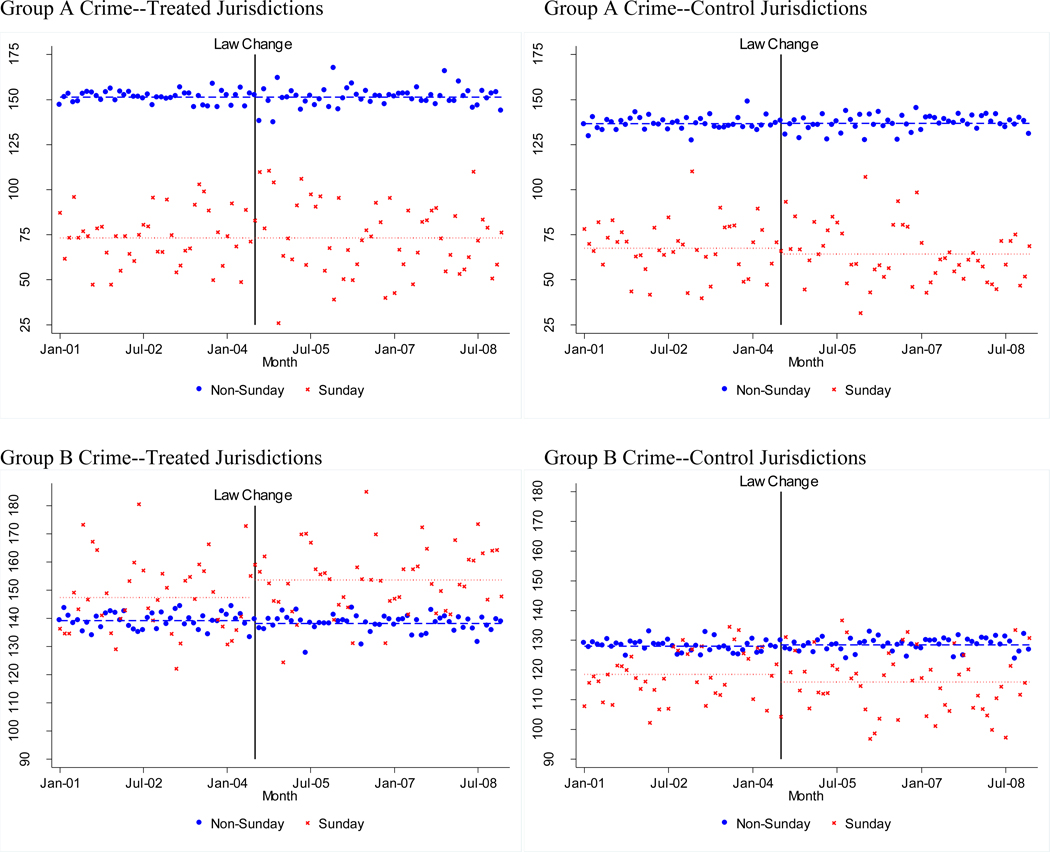

Figure 1 illustrates the DD and DDD identification approaches by plotting trends in aggregate crime counts in the 11 jurisdictions which had legalized Sunday packaged liquor sales after July 1, 2004 as compared to all other urban jurisdictions in Virginia that have not yet legalized such sales. Group A and Group B crimes are separately considered, and the data have been adjusted to remove seasonal effects. The figure indicates that Group A crime is less common on Sundays than on other days of the week in both repeal and non-repeal jurisdictions. More significantly, there is no evidence of an important change in the average number of Group A crimes in the repeal jurisdictions on either Sundays or other days of the week following the repeal. Similar stability in average Group A crime counts is observable in the non-repeal jurisdictions.

Figure 1.

Crime Patterns in Treated and Control Jurisdictions

Note: This figure plots the average daily crime counts by month for Group A and Group B crime in the eleven original jurisdictions in which Sunday packaged liquor sales were first legalized ("Treated Jurisdictions") and the other urban areas of Virginia ("Control Jurisdictions") in which such sales have not yet been legalized. Crime counts have been de-trended and de-seasonalized. Dashed lines represent the pre- and post-reform average crime counts.

For Group B crimes, a different pattern emerges. In the repeal jurisdictions, crime remains stable on days other than Sunday after July 2004, but increases on Sundays. In the control jurisdictions, in contrast, Sunday Group B crime actually fell slightly after July 2004. Figure 1 thus indicates that Group B crime rose after July 2004, but only on Sundays and only in repeal jurisdictions, as would be expected if these changes occurred because of the law change.

V. Results

The patterns in Figure 1 suggest that law change may have impacted some types of crime. Table 2 reports coefficient estimates from DD and DDD Poisson regressions that more formally test for this possibility as described above.16 These and all subsequent regressions reported in the paper also control for the occurrence of major holidays that may affect alcohol consumption, such as the Fourth of July or New Year's Day. Neither the DD nor the DDD specifications estimate a statistically significant effect of the law change on total Group A crime. Separately examining violent, property, and public order Group A crime also yields little evidence of an important effect of the law change on these crime categories, and for violent and property crime the DDD estimates are sufficiently precise so as to exclude increases of more than a few percentage points.17 However, for Group B crime there is evidence of a statistically significant impact of the liquor law repeal on crime, with the DDD estimate implying a 5.4% increase in Group B crime on Sundays following the law change.

Table 2.

Effects of Repeal on Group A and Group B Crime

| Crime Type | Mean crime count |

Estimation DD |

Approach DDD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Crime | 39.1 | .0595** | .0215* |

| (.0174) | (.0097) | ||

| Total Group A | 29.3 | .0257 | .0032 |

| (.0148) | (.0089) | ||

| Violent | 6.35 | .0527 | −.0187 |

| (.0309) | (.0181) | ||

| Property | 20.0 | .0270 | .0076 |

| (.0160) | (.0128) | ||

| Public Order | 2.94 | .0055 | .0120 |

| (.0427) | (.0485) | ||

| Total Group B | 9.77 | .1287* | .0530* |

| (.0565) | (.0209) | ||

| Disorderly conduct | 0.40 | .1772** | .1645* |

| (.0523) | (.0759) | ||

| Drunkenness | 1.45 | −.0006 | −.0211 |

| (.0498) | (.0388) | ||

| DUI | 1.17 | .0281 | −.0170 |

| (.0445) | (.0342) | ||

| Liquor law violations | 0.64 | .0670 | −.0048 |

| (.0499) | (.0642) | ||

| Other | 6.10 | .1137* | .0735* |

| (.0576) | (.0300) | ||

| N | 43375 | 99989 | |

Note: This table reports coefficients from Poisson regressions where the outcome variable is the count of crimes that occurred in a locality on a specific day and the primary explanatory variable is an indicator equal to 1 when Sunday packaged liquor sales are legal. The unit of observation is a locality/day. Each table entry reports a coefficient from a separate regression. For the differences-in-differences (DD) regressions, the first difference compares crimes committed on Sunday to crimes committed on other days of the week and the second difference compares crimes committed prior to the law change to crimes committed after the law change. The sample for the DD regressions is the 15 localities affected by the law change. The DD regressions include a full set of locality fixed effects, and all specifications include indicator variables controlling for the occurrence of New Year's Day, Christmas, Easter, Valentine's Day, the Fourth of July, and the Super Bowl. The DDD regressions expand the sample to the other 20 urban localities in the state, and identify the effects of the law change using an additional comparison of affected to unaffected localities. These regressions include a full set of locality/Sunday, day-of-week/month, and locality/month interactions as additional controls. For the DD regressions, standard errors are obtained through a wild cluster bootstrap procedure with 500 iterations; see Cameron, Gelbach, and Miller (2008) for further details. Unreported standard errors using traditional clustering are of very similar magnitude. For the DDD regressions, standard errors clustered on locality are reported in parentheses.

denotes an estimate that is statistically significant at the two-tailed 5% level, and

at the 1% level.

Among Group B crimes, there is a statistically significant increase of about 18% in disorderly conduct arrests following the liquor law repeal, which seems intuitive given that disorderly conduct is often precipitated by alcohol consumption. Whether one would expect increased DUI following repeal of a ban on liquor sales seems unclear--clearly if people consume packaged liquor purchased on Sunday before driving, this would tend to increase DUI, but greater availability of packaged liquor might also encourage consumption away from bars or restaurants, which could conceivably reduce intoxicated driving. Table 2 indicates that the law change did not affect drunk driving, at least as detected by police. This finding echoes that of Lovenheim and Steefel (2010), who find no relationship between repeal of Sunday sales bans and fatal vehicle accidents. There is also no apparent effect of the law change on liquor law violations, although this is perhaps unsurprising given that most such violations involve the sale of alcohol to minors in bars or restaurants, a phenomenon which may not be sensitive to policies related to packaged liquor sales. A considerable fraction of the overall effect of the law change on Group B crime is attributable to uncategorized or "Other" crimes, which increased by over 7% following the repeal.

The fact that much of the increase in Group B crime occurs for the “Other” category is disadvantageous as it is unclear exactly what types of crimes are represented by this miscellaneous classification. Intuitively, we expect the effect of a liquor law change to be most pronounced for crimes which may arise as a result of alcohol misuse. Because the NIBRS Group B records do not include a separate measure of alcohol involvement, we cannot directly examine whether the “Other” Group B crimes are indeed likely to involve alcohol use.

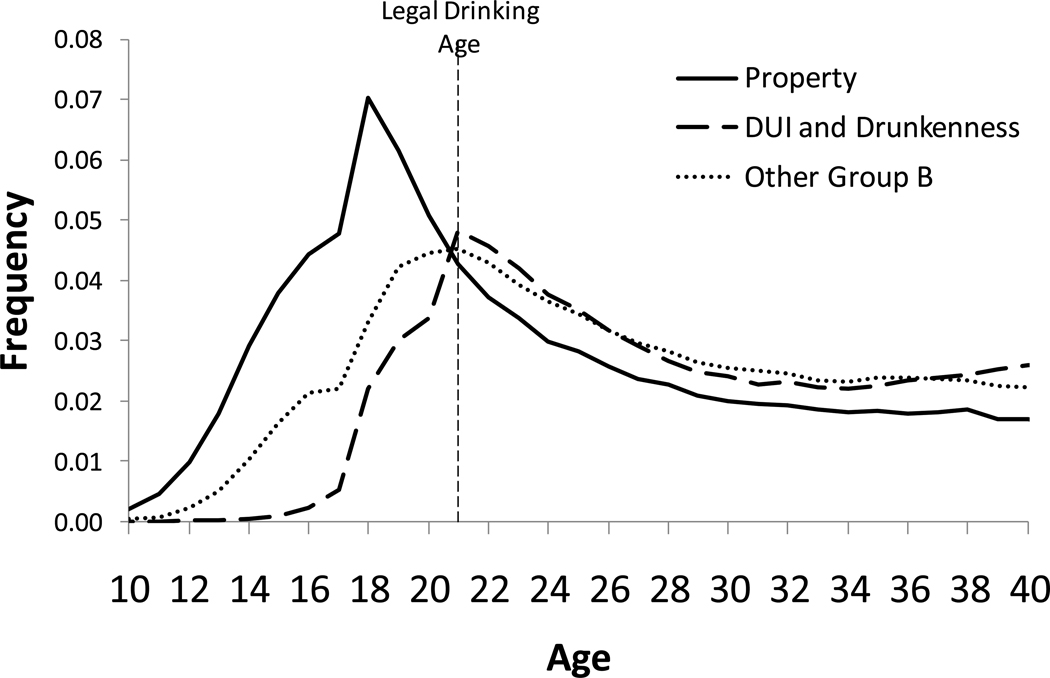

Nevertheless, one piece of evidence strongly suggests that these crimes do indeed often involve alcohol misuse. For typical crimes in the U.S., the rate of offending is highest in the late teenage years, leading to an age-crime curve that peaks in late adolescence (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1983, Farrington 1986, Laub and Sampson 2003). For crimes involving the misuse of alcohol, in contrast, the age-crime curve tends to peak around age 21, because alcohol use increases substantially once individuals reach the legal drinking age. Such disparate patterns are illustrated in Figure 2, which uses the Virginia NIBRS data to plot the age distribution of arrestees for various crimes. For property crime, the age-crime distribution follows the typical pattern, peaking prior to age 20 and declining steadily thereafter.18 When focusing on two crimes that by definition involve alcohol consumption, DUI and public intoxication, I obtain an age-crime distribution that is right-shifted and peaks at or shortly after the minimum legal drinking age. For the "Other" Group B crimes, the age-crime distribution peaks at age 21 and more closely resembles the distribution of alcohol-involved crimes rather than more general types of crime. Thus, the age-crime pattern for the “Other” Group B crimes strongly suggests that these crimes do indeed frequently involve the misuse of alcohol.

Figure 2.

Age Distribution of Arrestees in Virginia NIBRS Data

Note: This figure plots the frequency distribution by age of arrestees for various types of crime in Virginia. The figure is based on 372,886 property arrests, 427,673 DUI and drunkenness arrests, and 739,491 "Other" Group B (code 90Z) arrests. The age-crime curve for Other Group B crimes resembles those of alcohol-involved crimes rather than more standard types of crime.

Although Table 2 suggests that overall and specific categories of Group A crime were not affected by the repeal, it is nevertheless possible that certain more specific types of Group A crime were affected. Two categories of crime of particular interest are domestic crimes and crimes with reported involvement of alcohol. To identify domestic crimes, I use the NIBRS "Victim" data segment that records the relationship of each offender to each victim. I code as domestic any crime in which one of the offenders was a parent, spouse, or intimate partner of the victim; using this criterion approximately 7% of all Group A crimes are domestic crimes. The Group A records also include a separate indicator for crimes in which the offender was suspected of using drugs or alcohol shortly before or during the crime. 3.7% of all Group A crimes are coded as involving suspected alcohol use and 4.8% are coded as involving drug use. Given that these rates are below the levels of suspected alcohol and drug use in other sources of crime data, such as the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) (Greenfield 1998), it seems likely that this measure only captures crimes in which there was fairly obvious evidence of substance use by offenders.19 My estimates are thus likely to represent a lower bound on the true effect of the law change on these types of crimes.

Table 3 reports DD and DDD estimates of the impact of the law change on alcohol-involved and domestic Group A crimes. Effects on both overall domestic crime and domestic violence are small and statistically indistinguishable from zero. However, for alcohol-involved crime, I obtain a statistically-significant DDD coefficient of .10, indicating a 10.5% increase in alcohol-involved Group A crime following repeal. The DD estimate, while only marginally significant (p=.105), is of comparable magnitude.

Table 3.

Effects of Repeal on Domestic and Alcohol-Involved Group A Crime

| Type of Group A Crime | Estimation DD |

Approach DDD |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic | .0368 | −.0295 |

| (.0318) | (.0237) | |

| Domestic Violent | .0338 | −.0273 |

| (.0360) | (.0222) | |

| Alcohol Involved | .1043 | .1001* |

| (.0645) | (.0499) | |

| N | 43375 | 99989 |

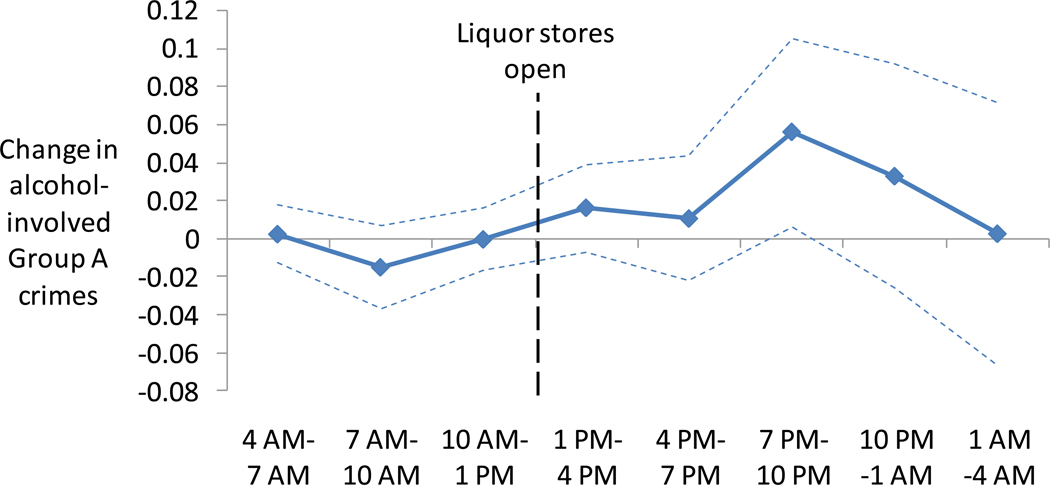

If the increase in alcohol-involved Group A crimes truly results from the expansion of packaged liquor sales on Sundays, we would probably expect the resulting crimes to occur during periods of the day when packaged liquor was available for purchase or consumption. Because Virginia ABC stores do not open until 1 p.m., increases in crime that occur prior to this hour seem unlikely to represent effects of the policy change. Figure 3 plots coefficients from DDD models in which the outcome is crime committed within specific three-hour windows on Sundays. To facilitate comparison of coefficient magnitudes across hours of the day, these models are estimated using OLS.20 Relative to the control jurisdictions, Sunday crime in the treatment jurisdictions is quite similar prior to 1 p.m., with no evidence of statistically significant differences, but crime differences rise beginning in the early afternoon, reaching a peak between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m., when alcohol consumption tends to be higher. The timing of the shift in crime is consistent with a crime effect arising from alcohol availability rather than other factors.

Figure 3.

Increase in Sunday Alcohol-Related Group A Crime by Time of Occurrence

Note: This figure plots coefficient estimates from triple-differences OLS regressions designed to measure the number of additional alcohol-related Group A crimes that occurred by time of occurrence as a result of the repeal. Dotted lines denote 95% confidence intervals. Further details regarding the regression specification can be found in the Table 2 notes.

We would also probably expect the crimes resulting from an increase in packaged liquor sales to occur in homes or on the road rather than in places such as bars or restaurants. In unreported regressions I estimated the impact of the repeal on crimes committed in specific locations. Although the resulting estimates were insufficiently precise to draw strong conclusions, the largest point estimates were observed for crime committed around residences, parking lots, and roads. There was no evidence of a change in Sunday Group A crime occurring in bars and restaurants or grocery and convenience stores following the law change.

Table 4 demonstrates that the basic finding that the repeal increased Group B crime generally and disorderly conduct specifically and alcohol-involved Group A crime persists across alternative specifications. For reference, in the first row I report the coefficient estimates from the original specifications discussed previously. Because Sunday liquor laws have only been repealed in larger, urban localities, for the main analysis I restricted attention to urban jurisdictions. Specification 2 of Table 4 re-examines the results using all jurisdictions in Virginia as the comparison group. Broadening the set of comparison geographies yields coefficients that are similar in magnitude and significance to the baseline.

Table 4.

Robustness Checks

| Crime Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specification | Total Crime |

Total Group B |

Disorderly Conduct |

Alcohol- Involved Group A |

| 1. Original (N=99989) | .0215* | .0530* | .1645* | .1001* |

| (.0097) | (.0209) | (.0759) | (.0499) | |

| 2. Include all urban and rural jurisdictions (N=387167) | .0260** | .0326 | .1715** | .0893* |

| (.0091) | (.0210) | (.0644) | (.0414) | |

| 3. Collapse into three groups (N=8766) | .0234 | .0459 | .2445** | .0883* |

| (.0125) | (.0255) | (.0569) | (.0409) | |

| 4. Negative binomial (N=99989) | .0185 | .0414 | .2063* | .1300* |

| (.0111) | (.0287) | (.0944) | (.0534) | |

| 5. OLS (N=99989) | 1.0202 | .9853* | .1487** | .1256* |

| (.5744) | (.4158) | (.0497) | (.0496) | |

| 6. Include locality-specific time trends (N=99989) | .0270** | .0482* | .1499* | .1054* |

| (.0093) | (.0193) | (.0715) | (.0437) | |

| 7. Measure days from 12 a.m. to 12 a.m. (N=99989) | .0173 | .0530* | .1645* | .0831* |

| (.0091) | (.0209) | (.0759) | (.0408) | |

| 8. Exclude tourist season (N=66028) | .0273* | .0840** | .2734** | .0887 |

| (.0122) | (.0250) | (.0857) | (.0543) | |

| 9. Limit sample to only repeal jurisdictions (N=43375) | .0344** | .0413 | .3925** | .0819 |

| (.0110) | (.0275) | (.0895) | (.0717) | |

| 10. First set of repeal jurisdictions only (N=85744) | .0176 | .0619* | .1122 | .1261* |

| (.0144) | (.0266) | (.0835) | (.0625) | |

| 11. Second set of repeal jurisdictions only (N=70859) | −.0249 | .0226 | .2402 | −.0056 |

| (.0249) | (.0784) | (.2253) | (.1097) | |

| Falsification Tests | ||||

| 12. Use Thursday as affected day (N=85720) | −.0065 | −.0195 | −.0016 | −.0252 |

| (.0069) | (.0189) | (.0873) | (.0485) | |

| 13. Use arrest rates as outcome (N=97403) | .0007 | |||

| (.0060) | ||||

Note: This table reports DDD estimates of the effects of the law change on crime using various samples and specifications. Specification 1 replicates results reported in Tables 2–3; see notes for those tables. Specification 2 expands the analysis sample to include all jurisdictions in Virginia. Specification 3 creates three synthetic jurisdictions by aggregating across the jurisdictions that early legalizers, later legalizers, and non-legailzers. Specification 4 estimates the effects of the law change using a negative binomial rather than Poisson model. Specification 5 uses OLS rather than Poisson; raw OLS coefficients are reported in the table. Specification 6 includes a full set of locality-specific quadratic time trends as additional controls. Specification 7 measures crime timing based on a 24-hour day beginning at 12 a.m. rather than 6 a.m. Specification 8 excludes May 15-Sept. 15 from the sample. Specification 9 limits the sample to the 15 jurisdictions in which the law had been repealed by 2008. Specification 10 limits the sample to the 10 jurisdictions with legal Sunday sales as of July 1, 2004 and the control jurisdictions. Specification 11 limits the sample to the 5 jurisdictions that legalized Sunday sales in 2008 and the control jurisdictions. Specification 12 assumes that Thursday crime rather than Sunday crime was affected by the law change. Specification 13 uses the daily share of incidents resulting in arrest (mean=.275) as an outcome and tests whether this changed due to the law change. This regression is estimated using OLS and is weighted by the total daily crime count. Due to the large samples and numbers of fixed effects included as covariates, Specifications 2, 4, and 6 include day-specific quintic polynomial time trends rather than a full set of day/month interactions. Each table entry reports the results from a unique regression.

The fact that jurisdictions that experienced repeal are clustered together geographically (Appendix Figure 1) might raise concerns regarding the appropriateness of approaching each affected jurisdiction as though it was independently treated. In Specification 3, I aggregate the data into three synthetic jurisdictions--early legalizers, later legalizers, and the rest of the state--and conduct the DDD analysis using only these three groups. Estimated impacts are quite similar to the baseline in both magnitude and significance.

Specification 4 uses a negative binomial model rather than a Poisson model to estimate the effects of the repeal. Estimated effects on total crime and total Group B crime become only marginally significant, but these point estimates are of comparable magnitude to the baseline, and effects on disorderly conduct and alcohol-involved Group A crime remain positive and significant. Specification 5 uses OLS rather than a count model and obtains equivalent results. In Specification 6, I include a set of locality-specific quadratic time trends as additional controls; these controls more fully account for the possibility that crime patterns over time might vary across jurisdictions in ways correlated with treatment. Because the basic identification approach contrasts crime across days of the week, one would not expect such trends, if they occur, to confound the estimates, and indeed controlling for additional time trends changes the estimates very little.

Although it seems most sensible to associate crimes occurring in the early morning with alcohol exposure on the prior day, specification 7 replicates the estimates defining the day using the traditional 24-hour period from 12 AM to 12 PM.21 Effects on alcohol-involved Group A crime decline slightly to 8.6%, but remain statistically significant. Specification 8 excludes the tourist season (May 15–Sept. 15) from the analysis to examine whether there is evidence that effects are driven primarily by changes in tourist traffic. I obtain point estimates of similar size when confining attention to periods of lower tourist activity, suggesting the impact of the laws is not driven solely by tourism. Specification 9 confines the analysis to only the jurisdictions in which the law was changed, either in 2004 or 2008. The "later legalizers" were presumably viewed by lawmakers as more comparable to the original legalizing jurisdictions than the state as a whole, so these localities might seem like a natural comparison group to use in constructing counterfactual crime rates for the early legalizers between July 2004 and July 2008. Defining the sample in this way increases the estimated impact on disorderly conduct but leaves the other point estimates relatively unchanged, although the smaller sample renders the effect estimate for alcohol-involved Group A crime somewhat imprecise.

Are increases in crime observed following both the original and subsequent liberalization of Sunday alcohol laws? Specification 10 limits the sample to jurisdictions that experienced a repeal in 2004 and the never-treated control jurisdictions, while Specification 11 focuses on the 2008 legalizers as compared to the never-treated control jurisdictions. Much of the effect of the law change appears concentrated among the earlier legalizers, with this sample demonstrating an 6.4% increase in Group B crime and a 13.4% increase in alcohol-involved Group A crime following repeal. Evidence of an impact of the law change on the later legalizers is weaker, with the largest estimated effect accruing for disorderly conduct, but no effect on alcohol-involved Group A crime. Because the number of treatment observations was relatively small for this latter sample (26 Sundays per jurisdiction between July 1, 2008 and the end of the sample), my ability to precisely estimate the effects of the law change is limited, so these results are not fully conclusive.

The next specifications of Table 4 report results of two falsification tests designed to examine the robustness of the triple-differences identification strategy. In the first falsification test (specification 12), I use crime occurring on Thursday rather than on Sunday as an outcome. Because crime displacement between Sundays and Thursdays is unlikely, if the triple-differences approach appropriately controls for unobserved differences across time and across jurisdictions, one should not expect to observe statistically significant effects on Thursday crime. Indeed, for this specification the point estimates are practically small and none is statistically significant, suggesting the DDD methodology may effectively account for confounding factors.

In the final row of Table 4 I test for the possibility that there were changes in enforcement associated with the law change. If police leaders believed that the additional availability of liquor would result in public disorder or unsafe driving, they may have increased the number of officers working Sunday shifts or otherwise shifted resources in an effort to respond to the policy. In this case, the increase in crime observed following the repeal might simply represent an increase in enforcement rather than a true change in the underlying amount of criminal activity. Although it seems doubtful to think that police leaders in most jurisdictions were closely attuned to current policies governing the availability of alcohol, enforcement adjustments could at least in theory explain some of my results.

Although I lack direct measures of enforcement effort, I am able to observe the share of reported crime incidents that resulted in arrest, which provides one proxy for the level of enforcement. Past research (e.g. Mas 2006) has demonstrated a correlation between enforcement inputs and the arrest/clearance rate. Specification 13 reports the law change coefficient from an OLS regression where the outcome is the share of Group A crime incidents in a particular day/jurisdiction that were ultimately were resolved with an arrest (mean=.275). The coefficient thus measures the extent to which the arrest probability changed for incidents occurring on Sundays in affected jurisdictions following the law change. Given many arrests are on-view arrests that occur when officers encounter criminal activity as a part of normal patrol duties, it seems plausible to expect that an increase in enforcement would be manifest in a higher arrest rate. However, the table demonstrates that there was almost no change in Sunday arrest rates following the law change, and the estimated coefficient is sufficiently precise so as to rule out changes in arrest rates of more than a few percentage points. It does not appear that these results can be explained primarily by changes in enforcement.

Although the robustness checks confirm that the repeal increased certain types of crime on Sunday, it is possible that this change did not represent a net increase in crime, but rather displacement of crime from other days of the week or other jurisdictions to those that were treated. For example, if prior to the law change consumers anticipated that liquor would be unavailable on Sunday and therefore purchased and consumed more liquor on Saturday than they would have otherwise, the law change might have reduced Saturday consumption and associated harms, including crime. Alternatively, the law change may have shifted general activity away from neighboring jurisdictions towards the affected jurisdictions on Sunday, in which case crime might increase in affected jurisdictions due to larger population exposure but decrease in neighboring jurisdictions.

Fortunately, the available data permit direct tests of these possibilities. Table 5 reports regression coefficients from augmented versions of equation (2) that include additional interactions between Saturdays and Mondays and the post-law change period in affected jurisdictions, thus allowing for the possibility of differential crime changes on Saturdays or Mondays. Similarly, I estimate specifications allowing separate impacts in jurisdictions neighboring the affected jurisdictions to test for geographic displacement. Although we continue to observe statistically significant effects of the law change on crime on Sundays (Specification 1), with effect sizes similar to those reported in Tables 2–3, the coefficients on Saturday and Monday crime are smaller, not statistically significant, and generally positive. This pattern suggests that the laws did not simply displace criminal activity from other days of the week. Specification 2, which tests for displacement across jurisdictions, indicates that the effects of the law remain positive and significant in the affected jurisdictions under an augmented specification. Point estimates on total crime and total Group B crime in neighboring jurisdictions are negative, which would indicate displacement, although these coefficients are imprecisely estimated, precluding strong conclusions. For disorderly conduct and alcohol involved Group A crime, however, there is no evidence of geographic displacement. Overall the estimates in Table 5 suggests that the law change generated net increases in crime rather than simply displacing crime.22

Table 5.

Intertemporal and Geographic Displacement

| Crime Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crime Impact On/In: | Total Crime | Total Group B | Disorderly Conduct |

Alcohol-Involved Group A |

| Specification 1 | ||||

| Saturday | .0013 | .0232 | .1518 | .0242 |

| (.0101) | (.0258) | (.1156) | (.0340) | |

| Sunday | .0278** | .0369 | .1931* | .1010* |

| (.0089) | (.0242) | (.0869) | (.0397) | |

| Monday | .0097 | −.0017 | −.0724 | .0402 |

| (.0061) | (.0176) | (.1192) | (.0344) | |

| Specification 2 | ||||

| Affected Jurisdiction | .0223* | .0241 | .1788** | .0954* |

| (.0093) | (.0219) | (.0660) | (.0421) | |

| Neighboring Jurisdiction | −.0225 | −.0535 | .0731 | .0355 |

| (.0174) | (.0339) | (.1080) | (.0876) | |

Note: This table reports triple-differences regression estimates of the effect of the repeal on crimes, allowing for the possibility of negative or positive crime spillovers from neighboring days or neighboring jurisdictions. Specification 1 measures the effects of the repeal on affected Sundays and the Saturdays and Mondays preceding and following these days. Specification 2 measures the effect of the repeal on affected jurisdictions allowing for separate impacts in neighboring jurisdictions. There are 7 neighboring jurisdictions potentially affected by the 2004 law change and 9 additional neighboring jurisdictions affected by the 2008 law change. Each specification/column reports coefficients from a unique regression. The samples includes all jurisdictions in Virginia and N=387167. See notes forTable 2.

VI. Cost Analysis

One natural question that arises in light of my finding that repeals of Sunday liquor sales restrictions increase crime is how the costs of this additional crime compare to the benefits of repeal. Unfortunately, a full-fledged cost-benefit analysis of the law change is infeasible, primarily due to the fact that an important benefit of the repeals is increased convenience to consumers from being able to more easily obtain packaged liquor on Sundays, but the value of this benefit to consumers remains unclear. However, given that packaged liquor sales are monopolized by the state of Virginia (as in many other states), one natural comparison that arises in the present context is a comparison of the costs of additional crime relative to the state revenues generated by additional Sunday sales.

Although the Virginia Department of Alcohol Beverage Control (VABC) does not specifically report profits from Sunday sales, these amounts can be estimated based upon information in the VABC annual financial statements. In FY 2008, VABC reported that sales of distilled spirits accounted for 99% of alcohol sales by revenue, and alcohol sales accounted for 96% of total revenue (VABC 2009).23 Thus, the vast majority of VABC profits can be attributed to liquor sales. FY 2008 total sales were $641 million and these sales generated $209 million in sales taxes and profits, suggesting that roughly 33% of the total amount of sales are returned to the state treasury.24 Between FY2005 and the end of 2008, VABC annual reports indicate that Sunday sales totaled approximately $37 million. Assuming that none of these purchases represent displaced sales from other days of the week, the repeal yielded roughly $12.2 million in additional state revenue.

A growing scholarly literature attempts to approximate the cost of representative crimes for use in policy analysis.25 Typical crime cost calculations attempt to incorporate such factors as pain and suffering of victims, lost offender and victim productivity, property losses, and costs to the criminal justice system. As noted by Miller, Cohen, and Wiersema (1996), a seminal work in this area, crime cost calculations are affected by multiple sources of uncertainty, however, meaning that crime cost calculations should be treated with appropriate caution. To monetize the losses to society resulting from additional crime generated by the policy change, we require estimates of the cost of a typical Group B crime and a typical alcohol-involved Group A crime. Cohen and Piquero (2009) estimate that low-level public order crimes generate about $500 per incident in total costs in 2007 dollars, with these costs essentially attributable to criminal justice costs. This value is roughly commensurate with Aos et al.'s (2001) estimate based on data from Washington state that a typical misdemeanor arrest generates approximately $1000 in police and prosecution costs. In the calculations that follow I consider costs in the range of $500 to $1000 per Group B crime.26

To calculate the cost of a representative alcohol-involved Group A crime in Virginia, I use the crime-specific cost values reported in Cohen and Piquero (2009) and McCollister, French, and Fang (2010) and apply them to the actual distribution of alcohol-involved crimes by type observed in the NIBRS data for Virginia. This calculation requires assuming that alcohol-involved crimes have similar costs or severity to crimes of the same type that do not involve alcohol use. Based on the crime cost estimates in Cohen and Piquero (2009), a typical alcohol-involved Group A crime cost $21,000 in year 2007 dollars. The McCollister, French, and Fang (2010) cost estimates yield a cost value of $34,100. Because homicides are considerably more costly than other types of crime, homicide can have a disproportionate impact on crime cost calculations. Excluding homicide from the calculations yields expected costs of $16,200 and $25,800 respectively.

A 5.4% increase in Group B crimes on Sundays following the repeal in the original set of repeal jurisdictions represents 1700 additional Group B crimes, generating a social cost of $.85 million–$1.7 million.27 Roughly 350 additional alcohol-involved Group A crimes can be attributed to the repeal, generating a social cost of $7.4 million–$11.9 million when including homicide or $5.7 million–$9.0 million if excluding homicide. Total estimated crime costs between 2004 and 2008 are on the order of $6.6–$13.6 million, a range similar in magnitude to the state revenues generated by the policy change. Although the Sunday liquor sales repeal may represent a net financial gain for the state, since many crime costs are not borne by state and local governments, the data suggest that crime costs may represent an important factor mitigating the benefits of Sunday liquor law liberalization.

VII. Conclusions

Although opponents of liberalization of laws governing the availability of alcohol on Sundays argue that heightened availability will generate negative social consequences, including increasing crime, prior empirical evidence for this proposition has been limited. When focusing on specific restrictions commonly in place in the U.S., such as restrictions on off-premises versus on-premises sales or sales of beer versus liquor, the theoretical relationship between availability and crime becomes even murkier due to the potential substitutability across forms of alcohol. This paper provides some of the first convincing evidence that expansion of Sunday alcohol sales can increase crime, demonstrating that the introduction of Sunday packaged liquor sales in selected jurisdictions in Virginia increased low-level property/public order crime by 5% and alcohol-involved serious crime by 10%. The timing and location of crime effects are consistent with a causal story based on alcohol availability, and the data suggest that these effects represent a net increase in crime rather than displacement across days of the week or localities. The social costs of these crimes are roughly equivalent to the state revenues generated through additional alcohol sales.

Debate over the proper level of alcohol availability, which benefits consumers, retailers, and tax authorities but which may also generate health care and crime externalities must clearly incorporate perspectives beyond the public health perspective. Nevertheless, clearly measuring the public health effects of alcohol restrictions represents a necessary pre-requisite for sensibly evaluating alcohol policy. Although the paper considers a specific form of alcohol restriction in a single state, given the widespread implementation of similar restrictions in other states its findings are likely to inform policy debates in a number of jurisdictions. Moreover, in demonstrating that alcohol sales expansions can be detrimental even when alternative means of consumption are already widely available, it provides new evidence that seemingly modest changes in alcohol policy can have important effects on public health. This fact counsels caution in the formulation of alcohol regulations, a policy domain in which even incremental changes can apparently have significant effects on local communities.

Research Highlights.

New legislation allowing sales of packed liquor on Sundays increased minor crime by 5% and alcohol-involved serious crime by 10%.

Allowing Sunday packed liquor sales had no effect on domestic violence.

The social cost of this additional crime approximately equaled state revenues from additional liquor sales.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Greg Ridgeway, Jens Ludwig, Mireille Jacobson, and numerous seminar participants for helpful comments. This publication was made possible by grant number R03AA018426 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) at the National Institutes of Health. The author bears sole responsibility for the contents of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Carpenter and Dobkin (2010) review this literature. Room and Rossow (2001) provide an overview of work linking alcohol consumption to crime.

Two exceptions are zero tolerance laws, examined in Carpenter (2007), and the minimum legal drinking age, analyzed in Carpenter and Dobkin (2008).

The findings of this study contributed to a decision to close Swedish monopoly stores on Saturdays beginning in 1982. However, in 2000 Saturday sales were re-introduced in two phases, and the effects of the re-introduction were evaluated in Norstrom and Skog (2003, 2005). They found no evidence of increases in assaults following the opening of stores on Saturdays.

An important difference between their setting and that of the present paper is that beer and wine are generally not sold in grocery and convenience stores in Canada.

Individual localities retain some autonomy over alcohol policy. In 2007, for example, by-the-glass liquor sales were legal in all of Virginia's independent cities but were not permitted in 11 of the state's 95 counties.

More specifically, Sunday sales were permitted in ABC stores located in the counties of Arlington, Fairfax, Prince William, and Loudoun, and the cities of Fairfax, Alexandria, Manassas, Manassas Park, Falls Church, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach. These jurisdictions were selected because of their substantial travel/tourism industries, which were perceived as being harmed by the sales restrictions.

In contrast to many other states, Virginia incorporates independent cities which have jurisdictional powers equivalent to counties. Because of this, even though both city and county departments are found in the state, individual agencies are almost always contained within a single jurisdiction.

Murder, rape, aggravated assault, robbery, burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, and arson.

NIBRS data classify offenses using 57 distinct offense codes that have been standardized across jurisdictions.

Specifically, I consider all non-treated jurisdictions with at least 10,000 residents that were more than 80% urban in 2000 as defined by the Census. All of the treated jurisdictions satisfy these criteria.

As demonstrated in Section V, my conclusions are not sensitive to this choice of control group.

Consistent with prior literature, for Group A crimes, which include data on the hour of occurrence of the crime, I measure days using periods from 6 a.m.–6 a.m. given that late evening alcohol use can often precipitate crimes that occur in the early morning hours.

Theoretically one could include a full set of calendar day fixed effects in Mt. As a practical matter, however, including thousands of fixed effects in a non-linear model significantly complicates estimation. For our basic specification we include a full set of month/year interactions in Mt, and we also consider other time controls such as polynomial trends in our robustness checks.

Although the Poisson maximum likelihood model is derived under the assumption of a Poisson data-generating process with equal mean and variance, Poisson regression provides consistent estimates of the conditional mean function across a wide range of data-generating processes, a feature that is not shared by other count models such as the negative binomial model (Wooldridge 2002). For this reason, the paper favors the Poisson model, although as robustness checks I report estimates using negative binomial models and linear models.

For example, a Major League baseball team relocated from Montreal to Washington D.C. at the end of 2004. This newly available entertainment option could have affected Sunday behavior, particularly in Northern Virginia.

Because the number of groups is arguably small in the DD regressions, for these regressions I follow Cameron, Gelbach, and Miller (2008) and report wild cluster-bootstrapped standard errors. For the DDD regressions I report cluster-robust standard errors with clustering at the jurisdiction level; these standard errors should be asymptotically consistent even when the Poisson assumption of equal mean and variance fails.

Further disaggregating into individual crimes such as rape or robbery yields no additional evidence of statistically significant impacts.

Drug crimes in the Virginia data show a very similar pattern.

Although levels of alcohol use vary between NIBRS and other data sources, other general patterns remain consistent--for example, in both the NCVS and NIBRS data, alcohol-using offenders are overrepresented among those committing rape and simple and aggravated assault.

Because the OLS DD and DDD estimates essentially involve comparisons of means across different groupings of the data and the number of observations underlying each mean are substantial, from various laws of large numbers we would expect even OLS to deliver consistent estimates of the effects of the law under a variety of data-generating processes.

This adjustment does not affect estimates for Group B crimes, because information on the hour of occurrence is not available for these crimes.

I also continue to obtain positive and significant effects on alcohol-involved Group A crime when coding treatment as occurring in affected or neighboring jurisdictions or on Sundays or Mondays.

VABC stores also sell lottery tickets.

Using data from prior years yields similar percentages.

Heaton (2010) summarizes the major approaches of this literature and discusses several prominent studies.

Because most of the impact occurs for “other” Group B crimes and the precise nature of these crimes is somewhat unclear, the true social cost of the additional Group B crimes cannot be known. However, it seems plausible to think that the cost of these crimes is relatively small.

Virginia's fiscal year begins July 1, so the revenue calculations do not include the second repeal period.

References

- Aos S, Phipps P, Barnoski R, Lieb R. The Comparative Costs and Benefits of Programs to Reduce Crime, v 4.0. 2001. Washington State Institute for Public Policy Report# 01-05-1201. [Google Scholar]

- Berman M, Hull T, May P. Alcohol Control and Injury Death in Alaska Native Communities: Wet, Damp and Dry under Alaska’s Local Option Law. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:311–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron C, Gelbach J, Miller D. Bootstrap-Based Improvements for Inference with Clustered Errors. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2008;90:414–427. [Google Scholar]

- Card D, Dahl G. Family Violence and Football: The Effect of Unexpected Emotional Cues on Violent Behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2010 doi: 10.1093/qje/qjr001. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C. Heavy Alcohol Use and Crime: Evidence from Underage Drunk-Driving Laws. Journal of Law and Economics. 2007;50:539–557. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C, Dobkin C. The Drinking Age, Alcohol Consumption, and Crime. 2008 Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C, Dobkin C. Alcohol Regulation and Crime. 2010. NBER Working Paper #15828. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C, Eisenberg D. The Effects of Sunday Sales Restrictions on Overall and Day-Specific Alcohol Consumption: Evidence from Canada. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(1):126–133. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Piquero A. New Evidence on the Monetary Value of Saving a High Risk Youth. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2009;29(1):25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Rust R, Steen S, Tidd S. Willingness-to-Pay for Crime Control Programs. Criminology. 2004;42:89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cook P, Moore M. Economic Perspectives on Reducing Alcohol-Related Violence. In: Martin Susan E., editor. Alcohol and Interpersonal Violence: Fostering Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1993. pp. 193–211. National Institutes of Health Publications No. 93-3469. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G, DellaVigna S. Does Movie Violence Increase Violent Crime? Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2009;124(2):677–734. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington D. Age and Crime. Crime and Justice. 1986;7:189–250. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld L. Alcohol and Crime: An Analysis of National Data on the Prevalence of Alcohol Involvement in Crime. Washington D.C: U.S. Department of Justice; 1998. Bureau of Justice Statistics Publication NCJ 168632. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald P, Freisthler B, Remer L, LaScala E, Treno A. Ecological Models of Alcohol Outlets and Violent Assaults: Crime Potentials and Geospatial Analysis. Addiction. 2006;101(5):666–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton P. Hidden in Plain Sight: What Cost-of-Crime Research Can Tell Us About Investing in Police. RAND OP-279-ISEC. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T, Gottfredson M. Age and the Explanation of Crime. American Journal of Sociology. 1983;89(3):552–584. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob B, Lefgren L. Are Idle Hands the Devils Workshop? Incapacitation, Concentration, and Juvenile Crime. American Economic Review. 2003;93(5):1560–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob B, Lefgren L, Moretti E. The Dynamics of Criminal Behavior: Evidence from Weather Shocks. Journal of Human Resources. 2007;42(3):489–527. [Google Scholar]

- Laub J, Sampson R. Shared Beginnings, Divergent Lives: Delinquent Boys to Age 70. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ligon J, Thyer B. The Effects of a Sunday Liquor Sales Ban on DUI Arrests. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1993;38:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ligon J, Thyer B, Lund R. Drinking, Eating, and Driving: Evaluating the Effects of Partially Removing a Sunday Liquor Sales Ban. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1996;42:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lovenheim M, Steefel D. Do Blue Laws Save Lives?: The Effect of Sunday Alcohol Sales Bans on Fatal Vehicle Accidents. 2010 Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz S. The Price of Alcohol, Wife Abuse, and Husband Abuse. Southern Economic Journal. 2000;67:279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz S. The Role of Alcohol and Drug Consumption in Determining Physical Violence and Weapon Carrying by Teenagers. Eastern Economic Journal. 2001;27:409–432. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz S, Grossman M. The Effects of Beer Taxes on Physical Child Abuse. Journal of Health Economics. 2000;19:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(99)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas A. Pay, Reference Points, and Police Performance. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2006;121(3):783–821. [Google Scholar]

- McCollister K, French M, Fang H. The Cost of Crime to Society: New Crime-Specific Estimates for Policy and Program Evaluation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108(1–2):98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan G, Lapham S. Legalized Sunday Packaged Alcohol Sales and Alcohol-Related Traffic Crashes and Crash Fatalities in New Mexico. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1944–1948. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T, Cohen M, Wersema B. Victim Costs and Consequences: A New Look. National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller T, Levy D, Cohen M, Cox K. Costs of Alcohol and Drug-Involved Crime. Prevention Science. 2006;7(4):333–342. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norström T, Skog O-J. Saturday Opening of Alcohol Retail Shops in Sweden: An Impact Analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:393–401. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norström T, Skog O-J. Saturday Opening of Alcohol Retail Shops in Sweden: An Experiment in Two Phases. Addiction. 2005;100:767–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson O, Wikström P-O. Effects of the Experimental Saturday Closing of Liquor Retail Stores in Sweden. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1982;11:325–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ray J, Moineddin R, Bell C, Thiruchelvam D, Creatore M, et al. Alcohol Sales and Risk of Serious Assault. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:725–731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D, Schnepel K. College Football Games and Crime. Journal of Sports Economics. 2009;10(1):68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Rossow I. The Share of Violence Attributable to Drinking: What Do We Need to Know and What Research Is Needed? Journal of Substance Use. 2001;6:218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Saffer H. Substance Abuse Control and Crime: Evidence from the National Household Survey of Drug Abuse. In: Grossman M, Hsieh C-R, editors. Economic Analysis of Substance Use and Abuse. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2001. pp. 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R, Mackinnon D, Dwyer J. The Risk of Assaultive Violence and Alcohol Availability in Los Angeles County. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(3):335–340. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan F, Reilly B, Schenzler C. Effects of Prices, Civil and Criminal Sanctions, and Law Enforcement on Alcohol-Related Mortality. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:454–465. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer P, Gorman D, Labouvie E, Ontkush M. Violent Crime and Alcohol Availability: Relationships in an Urban Community. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1998;19(3):303–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control. [accessed 10/7/2010];Annual Report 2008. 2009 Available at http://www.abc.state.va.us/admin/annual/annual.htm;

- Wooldridge J. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]