Abstract

The two primary photoreceptor-specific tetraspanins are retinal degeneration slow (RDS) and rod outer segment membrane protein-1 (ROM-1). These proteins associate together to form different complexes necessary for the proper structure of the photoreceptor outer segment rim region. Mutations in RDS cause blinding retinal degenerative disease in both rods and cones by mechanisms that remain unknown. Tetraspanins are implicated in a variety of cellular processes and exert their function via the formation of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains. This review focuses on correlations between RDS and other members of the tetraspanin superfamily, particularly emphasizing protein structure, complex assembly, and post-translational modifications, with the goal of furthering our understanding of the structural and functional role of RDS and ROM-1 in outer segment morphogenesis and maintenance, and our understanding of the pathogenesis associated with RDS and ROM-1 mutations.

Keywords: RDS, ROM1, Tetraspanin, Eye

Introduction

Retinal degeneration slow (RDS) is a tetraspanin protein critical for the formation and maintenance of photoreceptor outer segments (OSs). Mutations in RDS cause a variety of rod- and cone-dominant blinding diseases including autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, cone–rod dystrophy, and various forms of macular dystrophy (http://www.retina-international.com/sci-news/rdsmut.htm). The majority of work done on RDS has referred primarily to the body of vision literature, but it has become apparent that significant insight into RDS regulation and assembly may come from consideration of the function of other tetraspanin proteins and their similarities to RDS.

The variety in RDS-associated phenotypes seen in patients coupled with data from cone- and rod-dominant mouse models suggest that rods and cones have different requirements for RDS. Loss-of-function RDS mutations such as C214S and N244K have a greater effect on rods than on cones and cause autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa as a result of haploinsufficiency. In contrast, gain-of-function mutations such as R172W and N244H tend to cause cone-dominant diseases such as macular dystrophy. It is not clear why the two cell types should be so differently affected by different mutations.

Tetraspanin proteins in general are known to form large, multiprotein complexes known as the “tetraspanin web” or “tetraspanin-enriched microdomains” (TEMs) which mediate their function. Similarly, it has been hypothesized that differences in the composition of a larger protein complex, of which RDS oligomers are a major part, might help explain the differential requirement for RDS in rods versus cones. Tetraspanins are post-translationally modified and these modifications are functionally relevant for the formation of TEMs. This review focuses on parallels between RDS and other tetraspanins; specifically on protein structure, assembly, and post-translational modifications, with the goal of furthering our understanding of divergent rod and cone requirements for RDS.

Function

The main function of proteins within the tetraspanin family is to compartmentalize and concentrate a variety of cell-surface receptors within the plasma membrane. Each tetraspanin protein has the ability to interact with specific binding partners and with other family members in both homo- and heterocomplexes. These interactions combine to form the detergent-resistant lipid microdomains referred to as TEMs [1–3]. As a general rule, the function of these microdomains is determined by the binding partners of the individual tetraspanin proteins rather than by the intrinsic properties of the tetraspanins themselves. For example, tetraspanin proteins CD9 and CD81 link EWI-2, a cell-surface member of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) and known cytoskeletal regulator, with α3β1 integrin [4]. By mediating interactions between matrix and cytoskeletal regulatory components, CD9 and CD81 play a role in cell adhesion and motility. Similarly, CD81 and CD9 form a complex with αVβ5 integrin in retinal pigment epithelial cells which is important for phagocytosis of photoreceptor OSs [5]. As a result of this organizing function, tetraspanins and TEMs have been implicated in a variety of cellular functions including cell migration and invasion, cell fusion, intracellular trafficking, viral fusion and cell–cell adhesions. Insight into the physiological roles of tetraspanins comes from genetic as well as biochemical/physiological studies. For example, genetic studies have shown that mutations in the tetraspanin TM4SF2/A15 are associated with mental retardation while CD81 knockout mice exhibit immune system defects, particularly in B cells [6]. Other roles for tetraspanins include promoting gamete fusion (CD9/CD81), maintaining renal morphogenesis and function (CD53), maintaining OSs (RDS and its nonglycosylated homologue rod outer segment membrane protein-1, ROM-1), promoting (CD151) or inhibiting tumor metastasis (CD9, CD63, CD82), and modulating some types of infection (CD81) [6–10].

Rod photoreceptors mediate dim light vision and their photosensing OSs are composed of a tightly packed stack of membranous discs fully enclosed by the plasma membrane (Fig. 1a, b left). In contrast, the OSs of cone photoreceptors (which mediate day-time vision) are composed of a tightly packed stack of lamellae which are continuous with the plasma membrane (Fig. 1b right). RDS protein is exclusively located in the rim region of rod and cone OS discs and lamellae, and is not found in either the plasma membrane or the body of the disc [11]. RDS plays a fundamental role in maintaining OS structure, particularly the rim region [12]. Pinching of the rim is further discussed in subsequent sections, but mutations that interrupt the quaternary structure of RDS (C150S for example) can lead to the formation of large open membranous structures in the OS, rather than nicely flattened discs or lamellae [13]. In the wild-type rod-dominant mouse retina, the absence of RDS causes slow photoreceptor degeneration and an overt failure of OS formation [14]. In the heterozygous background, rod OSs form but are severely abnormal [15]. There are no discrete discs in the rds +/−; rather, large whorls of OS membrane form in a circular, fingerprint-like pattern [15, 16]. These phenotypes underscore the importance of RDS for both maintenance of OS structure and also initial elaboration of OSs. Specifically, the OS ultrastructure of the rds +/− suggests that RDS plays a key role in disc sizing and disc formation.

Fig. 1.

Photoreceptor structure. a Light micrograph (left) of the murine retina. The outer four retinal layers (OS outer segment, IS inner segment, ONL outer nuclear layer, OPL outer plexiform layer). Second order neurons synapse in the OPL and make up the rest of the retina (INL inner nuclear layer, IPL inner plexiform layer, GCL ganglion cell layer). Right Electron microscopic image of a rod OS/IS showing the flattened, completely enclosed discs. b Schematic diagram of rods and cones demonstrating the rim localization of RDS and ROM-1. c Schematic representation of RDS/ROM-1 complex assembly

In support of this, several studies using various lipid mixing assays have shown that RDS can actually mediate membrane fusion by a mechanism similar to that used by viral fusion proteins [17–21]. The fusion domain is found in the C-terminal region of RDS (Fig. 2), thus giving this region direct functional significance [22–25]. This function is an important difference between RDS and other tetraspanin proteins. The role of RDS as a direct fusogenic protein is unique among the tetraspanin family [24]. While other tetraspanin proteins have been implicated in membrane fusion, they are thought to participate as protein organizers rather than as actual fusion proteins [2]. The fusogenic region of the RDS C-terminus consists of an α-helical region from position 313 to 327 [25]. The proline at position 296 has been shown to be particularly important: it enhances the fusogenic capabilities of RDS [24]. Early hypotheses posited that RDS is involved in pinching off or zipping the disc rim at the base of the OS in rods when the discs reach the appropriate size and may be involved in the regulation of disc shedding at the apical side of the OS [17, 26]. These functional hypotheses are consistent with biochemical data on RDS-mediated membrane fusion [18, 25].

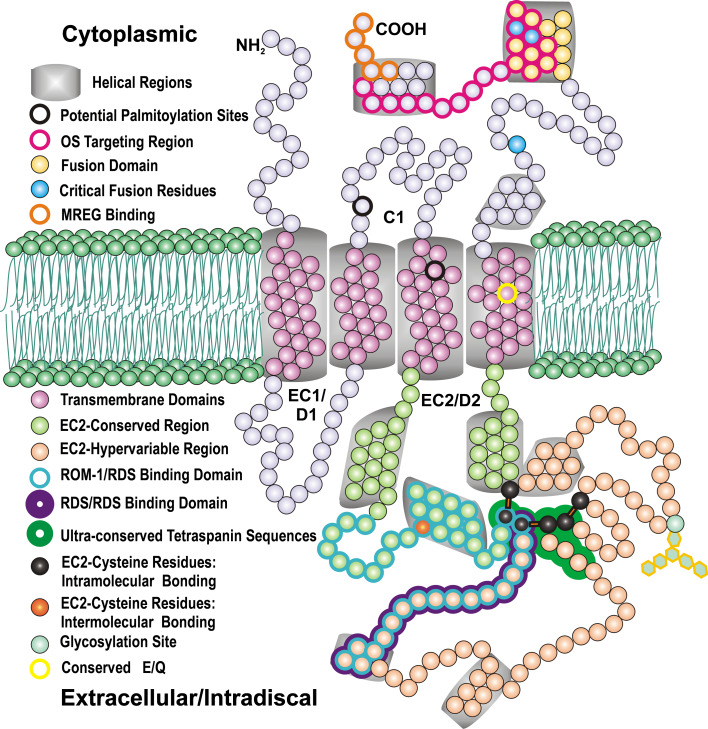

Fig. 2.

Structural features of RDS. RDS and ROM-1 contain four transmembrane domains (pink), two intradiscal/extracellular loops (EC1/D1, EC2/D2), cytoplasmic N- and C-termini, and a small cytoplasmic loop (C1). The D2 loop contains a highly conserved tetraspanin region (light green) and a hypervariable region (peach). Several helical regions (gray) are found in both the D2 loop and the C-terminal region. Several sites are relevant for RDS complex assembly: the RDS–RDS interacting region (purple outline), the RDS–ROM-1 interacting region (teal outline), and the RDS–melanoregulin (MREG) interacting region (orange outline). Residues important for post-translational modifications are also indicated: glycosylation (pale aqua), intermolecular disulfide bonding (orange), intramolecular disulfide bonding (black), and potential palmitoylation (black outline)

Localization and trafficking

Tetraspanins typically localize to the plasma membrane. A few notable exceptions include RDS and ROM-1, but also CD63, which is ubiquitously expressed and localizes predominantly to late endosomal membranes and lysosomes as well as the cell surface [27]. RDS is localized to the rim region of photoreceptor OS discs and lamellae. In keeping with this altered localization, the domains of RDS that would be extracellular in other tetraspanins are located inside the rod photoreceptor disc lumen and extracellularly in cone lamellae.

While the cytoplasmic domains of tetraspanins are varied within the tetraspanin family, they are conserved among the various orthologues of individual tetraspanins [28]. This is especially true for the C-terminal region of most tetraspanins and suggests that the C-terminal region may play a significant role in the function of individual family members [28]. The trafficking sequence necessary for the proper subcellular localization of tetraspanins is present within the cytoplasmic domains with specific sequences being found within the C-terminal region. Several tetraspanins have a YXXØ motif (where Ø is a bulky, hydrophobic residue) in the C-terminus thought to be important for trafficking. This motif has been shown to be necessary for targeting CD63 to its proper location, the late endosome [28]. It should be noted that several members of the tetraspanin family localize to specific cellular membranes towards which they have no obvious targeting sequence. This is thought to be regulated through cis interactions with other proteins including other tetraspanin proteins which are capable of directed sorting [28].

In common with other tetraspanins, RDS also has a trafficking signal in its C-terminus, but it does not share the common YXXØ motif. Experiments using GFP fusion proteins in Xenopus photoreceptors indicate that RDS transport from the trans-Golgi in the inner segment to the OS rims is directed by the region 317–336 (Figs. 2 and 3 bright pink); [29]. This region is completely conserved among mammalian RDS orthologues, but is not found in ROM-1, non-glycosylated binding partner of RDS. As a result of the unique architecture of the photoreceptor inner segment/OS and the specific localization of RDS within that structure, it is not surprising that RDS has a different trafficking signal than other tetraspanins. The major membrane component of the OSs is opsin. Much is known about the mechanism of opsin-based vesicular targeting to the OS, and it has been shown that opsin and RDS traffic in separate vesicles by separate pathways [13, 30]. Aside from this, little else is known about the precise mechanism of RDS trafficking to rod and cone OSs.

Fig. 3.

Sequence alignment of RDS and ROM-1 orthologues: human, bovine, dog, cat, rat, mouse and skate, RDS; CRDS1 and CRDS2 chicken RDS; XRDS 35, 36 and 38 Xenopus RDS; and human, bovine and mouse ROM-1. The coloring is consistent with Fig. 2: light pink transmembrane domains, teal glycosylation consensus sites, orange intermolecular bonding site, green ultraconserved tetraspanin sequences, blue critical fusion residues, bright pink OS targeting region, yellow highly conserved E/Q in TM4; asterisks completely conserved residues, square symbols highly conserved residues

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis indicates that the tetraspanin superfamily (TM4SF) comprises four major families; (1) the CD family, containing many common vertebrate and invertebrate tetraspanins including CD9, CD81, and CD151, (2) the CD63 family, which contains CD63 and several Drosophila tetraspanins, (3) the uroplakin family, and (4) the RDS family which contains RDS, ROM-1, TSPAN10, TSPAN5, TSPAN14, and TSPAN15 among others [31]. In addition, at the base of the TM4SF gene tree there are several plant/fungi/amoebae tetraspanins that are not part of the four major families [31, 32] but which share a common ancestor with them. In addition to conserved amino acid sequence/protein structure (discussed below) many tetraspanins share conserved gene structure and intron/exon boundaries. The most common tetraspanin gene structure involves eight exons, or nine exons with the first being nontranslated. This pattern is found in genes from all four of the large TM4SF families. Interestingly, however, RDS, ROM-1 and other closely related members of the RDS family have a divergent genetic structure. RDS, ROM-1, and TSPAN10 homologues most often have only three exons. This three-exon structure is highly conserved among RDS/ROM-1 genes, with only a few diverging.

RDS and ROM-1 are only found in vertebrates [31]. Using the ENSEMBL database (http://www.ensembl.org/ [33]) we generated a gene tree for the RDS/ROM-1 gene family. This analysis predicts that the group of ROM-1 genes arose as a duplication in the Euteleostomi (bony vertebrates) clade. We have previously characterized a well-conserved RDS homologue in skate [34] (cartilaginous fish – Chondrichthyes) which diverged prior to the duplication that gave rise to ROM-1. In keeping with this earlier divergence, skate RDS consists of only two exons. Exon 1 of skate RDS corresponds to exon 1 in other RDS/ROM-1 family members while skate RDS exon 2 corresponds to exons 2–3 [34].

RDS is highly conserved in bony fish, birds, and mammals. ROM-1 is present in most but not all analyzed fish and mammalian species. It is not found in the bird genomes analyzed. Of particular interest is the absence of ROM-1 in several primate genomes including the mouse lemur, a species gaining popularity as a laboratory animal. The absence of ROM-1 in these genomes supports its role as a supportive player in retinal structure, in contrast to the primary role of RDS. Table 1 summarizes the RDS/ROM-1 genes found in the gene tree we generated. More detailed amino acid sequence analysis on the species shown in Fig. 3 indicates that pathological mutations that cause RP are completely conserved in all the species examined. Mutations that cause macular dystrophy are highly conserved in mammalian species, but exhibit some divergence in chicken and frog, suggesting that the role of RDS in cones may vary by species [34].

Table 1.

List of RDS/ROM-1 genes found in a vertebrate gene tree generated using all vertebrate species in the ENSEMBL database

| Clade | Common name | Species | No. of genes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDS | ROM-1 | |||

| Tetrapoda | Frog | Xenopus tropicalis | 2 | 1 |

| Clupeocephala | Medaka | Oryzias latipes | 3 | 2 |

| Stickleback | Gasterosteus aculeatus | 4 | 2 | |

| Fugu | Takifugu rubripes | 4 | 2 | |

| Zebrafish | Danio rerio | 4 | 2 | |

| Tetraodon | Tetraodon nigroviridis | 4 | 1 | |

| Sauria | Turkey | Meleagris gallopavo | 2 | 0 |

| Chicken | Gallus gallus | 2 | 0 | |

| Zebra finch | Taeniopygia guttata | 2 | 0 | |

| Anole lizard | Anolis carolinensis | 2 | 0 | |

| Mammalia | Armadillo | Dasypus novemcinctus | 1 | 1 |

| Hyrax | Procavia capensis | 1 | 1 | |

| Lesser hedgehog | Echinops telfairi | 1 | 1 | |

| Tree shrew | Tupaia belangeri | 1 | 1 | |

| Wallaby | Macropus eugenii | 1 | 1 | |

| Opossum | Monodelphis domesctica | 2 | 1 | |

| Platypus | Ornithorhynchus anatinus | 1 | 0 | |

| African elephant | Loxodonta africana | 1 | 1 | |

| Laurasiatheria | Megabat | Pteropus vampyrus | 1 | 1 |

| Microbat | Myotis lucifugus | 1 | 1 | |

| Panda | Ailuropoda melanoleuca | 1 | 1 | |

| Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | 1 | 1 | |

| Cat | Felis catus | 1 | 1 | |

| Alpaca | Vicugna pacos | 1 | 0 | |

| Pig | Sus scrofa | 1 | 0 | |

| Cow | Bos taurus | 1 | 1 | |

| Horse | Equus caballus | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottlenose dolphin | Tursiops truncatus | 1 | 1 | |

| Hedgehog | Erinaceus europaeus | 1 | 1 | |

| Glires | Guinea pig | Cavia porcellus | 1 | 1 |

| Rat | Rattus norvegicus | 1 | 1 | |

| Mouse | Mus musculus | 1 | 1 | |

| Kangaroo rat | Dipodomys ordii | 1 | 1 | |

| Rabbit | Oryctolagus cuniculus | 1 | 1 | |

| Squirrel | Spermophilus tridecemlineatus | 1 | 0 | |

| Pika | Ochotona princeps | 1 | 1 | |

| Primates | Human | Homo sapiens | 1 | 1 |

| Chimpanzee | Pan troglodytes | 1 | 1 | |

| Gorilla | Gorilla gorilla | 1 | 1 | |

| Orangutan | Pongo abelii | 1 | 1 | |

| Gibbon | Nomascus leucogenys | 1 | 1 | |

| Macaque | Macaca mulatta | 1 | 1 | |

| Marmoset | Callithrix jacchus | 1 | 1 | |

| Tarsier | Tarsius syrichta | 1 | 0 | |

| Mouse lemur | Microcebus murinus | 1 | 0 | |

| Bushbaby | Otolemur garnettii | 1 | 0 | |

Structure and complex assembly

The tetraspanin family of integral membrane proteins is differentiated from other proteins with four transmembrane (TM) domains by conserved secondary and tertiary structures along with conserved sequence motifs [2]. Tetraspanins, including RDS and ROM-1 exhibit a conserved heptad repeat (abcdefg)n in TM1–3 characterized by specific residues at the a and d positions [35]. Conservation at these residues is thought to be important for proper protein packing in the membrane [35]. The fourth tetraspanin TM domain is characterized by conservation of a glutamine/glutamate, and this residue is found in all known RDS/ROM-1 orthologues (Figs. 2 and 3 yellow). Both the N- and C-terminal domains are on the cytosolic side of the membrane, and the TM domains are linked by two extracellular loops and one cytosolic loop. The two extracellular loops are not symmetrical: extracellular loop 1 (EC1) which links TM domains 1 and 2 is usually much smaller than extracellular loop 2 (EC2) which links TM domains 3 and 4 (Figs. 2 and 3).

EC2 is the domain in which the majority of tetraspanin-defining features reside. This region contains all of the conserved cysteine residues that form disulfide bonds. Furthermore, EC2 is also important for the formation of multiprotein complexes (TEMs) and for homo- and hetero-oligomer formation [1, 36]. X-ray crystallography of EC2 from CD81 and extensive computational modeling of other tetraspanins (including RDS) indicate that EC2 consists of two regions [37, 38]. The first region is highly conserved between tetraspanins while the second is hypervariable in both sequence and length, and exhibits almost no sequence homology across family members other than a few ultraconserved cysteine residues (as shown in RDS in Fig. 2) [38]. Seigneuret et al. provide an excellent discussion of the secondary and tertiary structure of tetraspanin EC2s [38]. The conserved region of the EC2 loop consists of three alpha helical structures with the variable region between the second and third conserved helices. The three conserved alpha helices are thought to associate into a stable disulfide-linked tertiary structure that is common to all tetraspanins. In RDS, the conserved region corresponds approximately to residues 125–67 and 250–263, while the variable region is one of the largest within the tetraspanin family and corresponds to residues 168–249 [38]. In addition to the three conserved helical regions in the EC2, RDS is also predicted to have two smaller helical regions in its EC2 hypervariable region [38].

The formation of multiprotein complexes (TEMs) and their segregation in detergent-resistant membrane fractions that are distinct from lipid rafts is essential for tetraspanin function. Complex formation is governed by primary and secondary interactions between individual tetraspanin proteins and their various binding partners. Tetraspanins typically emerge from the Golgi as noncovalently bound homo- and heterodimers with other tetraspanins [39]. These interactions are thought to occur predominantly within the conserved region of the EC2 loop [39]. Crystallographic data support this idea and indicate that CD81 homodimerization occurs between the first and the third conserved EC2 helices of two adjacent monomers [37].

Once at their target membranes, tetraspanins interact either directly or indirectly with a variety of proteins including other tetraspanins, integrins, members of the IgSF, other cell surface receptors and the cellular cytoskeleton to form TEMs [3]. A distinction is usually made between primary tetraspanin binding partners, whose interactions are preserved in detergents such as Brij 96 and Triton X-100, and looser secondary interacting partners, whose interactions are harder to detect and are usually only preserved in the presence of milder detergents such as CHAPS and Brij 99 or in the presence of divalent cations/absence of EDTA. Some of these interactions are mediated by the EC2 loop, some are mediated or enhanced by tetraspanin palmitoylation [40] (see below), and some are mediated by the cytoplasmic domains. For example, CD9 and CD82 have both been shown to associate with protein kinase C at either their N or C termini [41].

In the rod photoreceptor inner segment, RDS assembles into noncovalently bound homo- or heterotetramers with its nonglycosylated homologue ROM-1 [42, 43]. These tetramers are trafficked into the OS where they further assemble into intermediate and higher order oligomers held together by disulfide bonds (Fig. 1c; further discussed below) [44, 45]. Based on studies in the cone-dominant nrl −/− retina, rods and cones have similar types of RDS complexes, (i.e. tetrameric, intermediate, and higher order oligomers) [42], but it is not clear whether complex assembly, trafficking, and relative quantity are the same in both rods and cones.

The primary binding partners of RDS are itself and ROM-1. Noncovalent RDS homo associations are mediated by EC2 (also known as the D2 loop since it is intradiscal in the case of RDS), specifically by the region between C165 and N182, while the hetero associations between RDS and ROM-1 are mediated by the region between Y140 and N182 [36]. RDS/ROM-1 hetero associations require the conserved region of EC2, consistent with tetraspanin–tetraspanin interactions in other tissues. Interestingly, in contrast to other tetraspanins, noncovalent RDS homo interactions occur in the hypervariable region of EC2, rather than in the conserved region. This difference may be related to the necessity for RDS to form higher order homo-oligomers, in contrast to other tetraspanins, which usually form only homodimers and larger heteromeric complexes.

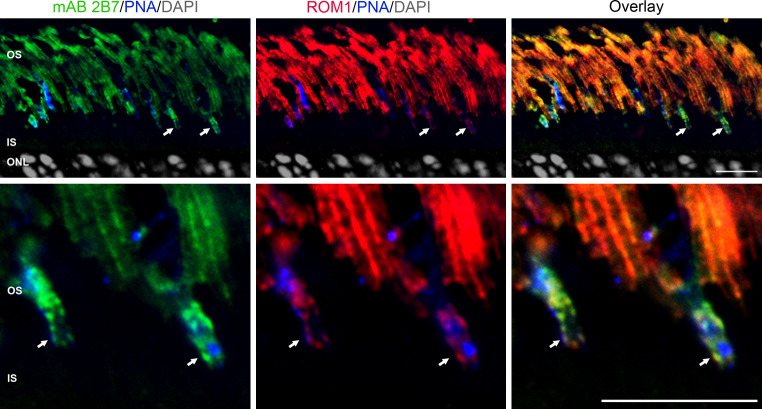

Elimination of ROM-1 causes only mild rod defects, primarily an enlargement of OS discs [46], but the role of ROM-1 in cones has not been studied. We have demonstrated that ROM-1 does not participate in higher order RDS homo-oligomers, and is only found in tetramers and intermediate sized RDS complexes [42]. We have also shown that cones are more sensitive than rods to small conformational changes in the higher order oligomers [13]. It is possible that differences in ROM-1/RDS interactions or differences in the ratio of ROM-1/RDS levels may explain part of the apparent differential requirement for RDS in rods versus cones. The relative levels of RDS and ROM-1 in cones versus rods have not been determined since cones and rods cannot be separated biochemically. To qualitatively assess the ratio of ROM-1/RDS in rods versus cones, we colabeled retinal sections with ROM-1 polyclonal (ROM-1 red) and RDS monoclonal (mAb 2B7 green) antibodies. Sections were counterlabeled with peanut agglutinin (PNA blue) and DAPI (gray) to mark cone OSs and nuclei, respectively. As demonstrated by the anti-ROM-1 and anti-RDS labeling in Fig. 4, ROM-1 and RDS are expressed in cone and rod OSs (arrows point to cone OSs). However, the overlay panel qualitatively shows that the ratio of ROM-1/RDS is much lower in cones than rods (observe greenish–yellow in cones compared to orangeish–yellow in rods).

Fig. 4.

The ratio of ROM-1/RDS is lower in cones than rods. Frozen retinal sections taken from P30 mice were labeled with mAb 2B7 against RDS (green) and rabbit polyclonal antibody against ROM-1 (red). Sections were counterlabeled with peanut agglutinin (PNA blue) to mark cone OS (arrows), and DAPI (gray). Bottom row higher magnification of top row; arrows cone OS. Both cones and rods express RDS and ROM-1, but the color of cones versus rods in the overlay indicates that the ratio of the two proteins (ROM-1/RDS) is less in cones than rods. images shown are single planes from a confocal stack (scale bar 20 μm)

It has been demonstrated that ROM-1 enhances the fusogenic activity of RDS, although ROM-1 alone cannot mediate membrane fusion [19]. If one of the roles of ROM-1 is to assist in RDS-mediated membrane fusion, it makes sense that rods require more ROM-1 relative to RDS than cones, since membrane fusion at the base of the OS occurs in rods but not in cones. Furthermore, if cones require more higher order RDS homo-oligomers (as a fraction of total RDS) than rods, it also makes sense to have less ROM-1 in cones.

In addition to ROM-1, RDS is known to interact with three additional proteins. First, it has been shown by coimmunoprecipitation that in rods, RDS interacts with the glutamic acid-rich protein (GARP). The gene encoding GARP exhibits three splice forms: two are free cytoplasmic forms and the third is the β subunit of the rod cyclic nucleotide gated (CNG) channel which exhibits the GARP domain on its N-terminus. This channel is expressed in the rod OS plasma membrane, and it has been hypothesized that binding of RDS to CNG-GARP might anchor the disc rim to the plasma membrane, while binding of RDS to free GARP might bridge adjacent discs [47]. Although the region of RDS which binds to GARP has not been mapped, logic suggests that a cytoplasmic region is involved. Interestingly, GARP is not expressed in cones, either in free form or as part of the cone CNG channel, and RDS does not bind to the β subunit of the cone CNG channel [48].

The second known RDS binding partner is melanoregulin (MREG). MREG is a regulator of organelle biogenesis originally identified as a requirement for melanosome transport but is found expressed in the inner segment and basal OS of rod photoreceptors [23]. There is no conclusive data about MREG expression or localization in cones. MREG has been shown to bind the last five residues of the RDS C-terminus. Membrane fusion assays have demonstrated that the rate of RDS-mediated membrane fusion is reduced in the presence of soluble MREG. It has been proposed that when MREG binds the C-terminal region of RDS, it blocks the fusogenic properties of this domain, thereby regulating nascent disc formation in rods [23].

Calmodulin (CaM) is another regulator of RDS membrane fusion activity that has been found to be associated with RDS. CaM binds RDS in a calcium-dependent manner [49]. The putative CaM binding site is predicted to be between residues E314 and G329, roughly corresponding to the membrane fusion domain of the RDS C-terminus. It has been proposed that this binding plays a role in the apical shedding of the rod OS by regulating the fusogenic properties of the RDS C-terminus [49]. MREG and CaM binding data suggest that RDS-mediated membrane fusion is differently regulated based on subcellular localization of the interacting partners and cellular conditions.

Although it is a subject of interest, no additional RDS binding partners or other members of a putative RDS-mediated TEM have yet been identified. Strikingly, in spite of the role RDS plays in maintaining OS structure and the precedents set by other tetraspanins for tetraspanin-mediated regulation of matrix/cytoskeleton, no RDS binding partners with matrix/cytoskeletal regulatory functions have yet been found.

Post-translational modifications

Cysteine residues and disulfide bond formation

All tetraspanins contain at least four cysteine residues in EC2, including an absolutely conserved CCG motif and a conserved PXSCC motif (Figs. 2 and 3) [28]. Most tetraspanins contain an additional pair of EC2 cysteines for a total of six [28]. These cysteines form intramolecular disulfide bonds with each other to help define the tertiary structure of EC2 [1, 28]. Since EC2 is responsible for a variety of intermolecular interactions, destabilization and disorganization of this region through the loss of disulfide bonds can have a negative impact on the ability of tetraspanin proteins to associate with each other and with their binding partners. For example, mutations in two separate cysteine residues of the EC2 loop of CD81 have been shown to create a protein that has lost a disulfide bond and is incapable of forming dimers [50]. RDS has these six highly conserved cysteine residues (C165, C166, C213, C214, C222, C250) in EC2 which form intramolecular disulfide bonds [44]. If any of these six residues are mutated, RDS fails to form normal complexes and also forms large aggregates, probably due to improper folding [44]. Interestingly, RDS and ROM-1 contain an additional cysteine in the EC2. This seventh cysteine (C150) is necessary for the formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds [42, 44]. Although this cysteine resides in the region of EC2 that is highly conserved, no other tetraspanins exhibit a cysteine in this region. As shown in Fig. 2, C150 is located between the first and second putative conserved EC2 helical region at the edge of a small loop that protrudes into the intradiscal space.

As a result of this seventh EC2 cysteine, RDS forms covalent homocomplexes in addition to noncovalent ones. In mice which only express transgenic RDS without this cysteine (C150S-RDS) noncovalently bound tetramers are detected but they do not assemble into higher order oligomers [42, 44]. Furthermore, C150S-RDS is not able to support OS formation in the absence of endogenous RDS. In vivo higher order disulfide-bonded RDS homo-oligomers are responsible for maintaining the pinched morphology of the OS disc rim. Support for this role has been found from in vitro experiments using C150S-RDS [51]. In this study, wild-type RDS was able to flatten microsomal vesicles, giving them a disc-like shape; however, this striking morphology was lost in the presence of C150S-RDS [51].

As mentioned above, ROM-1 is not found in higher order RDS homo-oligomers, although it has a seventh unpaired cysteine in its EC2. The presence of ROM-1 dimers on nonreducing SDS-PAGE gels suggests that ROM-1 can form intermolecular disulfide bonds, but it is not clear whether it ever forms them with RDS. Interestingly, ablation of C150-mediated disulfide bonding has a much more severe effect in cones than in rods. C150S-RDS causes a severe, dominant structural and functional degeneration in cones but leaves rods unaffected when endogenous RDS is present. This striking difference underscores a potential difference in the role of RDS higher order complexes in cones versus rods. The critical role of intermolecular disulfide bonding for RDS function highlights an area of divergence from other tetraspanins.

Palmitoylation

One of the most common and functionally relevant tetraspanin posttranslational modifications is palmitoylation. While there is no known palmitoylation consensus sequence, S-acylation usually occurs on a cysteine residue near or just within the TM domains on the cytoplasmic side of the protein. Palmitoylated residues on tetraspanins play a key role in the formation of secondary associations that enable the assembly of TEMs [40]. Palmitoylation has been shown to increase the affinity of tetraspanins for their primary binding partners, but has no effect on transport to the plasma membrane or partitioning to the detergent-resistant membrane fraction [40]. Studies in which palmitoylated cysteines in CD9 were sequentially mutated to serine have demonstrated that unpalmitoylated CD9/CD81 complexes are more sensitive to EDTA disruption than the palmitoylated complexes [52]. Similarly, inhibition of palmitoylation has been shown to prevent the association of CD63 and CD9 with integrin αIIbβ3 in activated platelets [53]. Abolishing this interaction prevents the activation of integrin-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangements in platelets and prevents platelet aggregation in vitro [53]. As a whole, palmitoylation has been shown to be critical to the overall ability of tetraspanins to form TEMs.

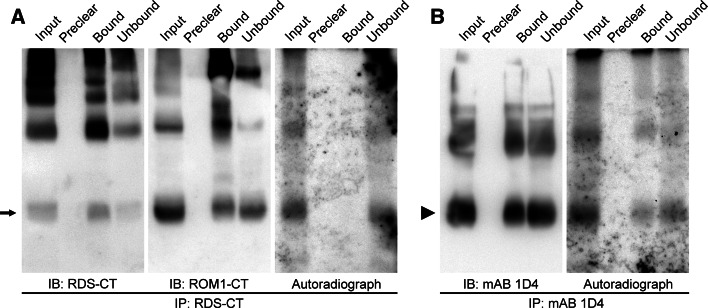

RDS has two cytoplasmic cysteines, C82 and C105 (Figs. 2 and 3 red), that could potentially be palmitoylated. In contrast, ROM-1 does not have any membrane-proximal cytoplasmic cysteines (Fig. 3 light purple). To examine whether RDS is palmitoylated, isolated wild-type murine retinas were incubated in media supplemented with [3H]-palmitate for 12 h. Retinal lysates underwent immunoprecipitation using antibodies for the C-terminus of RDS (RDS-CT) as described previously [45]. Immunoprecipitants were separated via SDS-PAGE on paired reducing gels and subsequently analyzed by either western blotting or autoradiography. Immunoprecipitation for rhodopsin (mAb 1D4), which is known to be palmitoylated, was used as a positive control. Western blot analysis (Fig. 5a, b left panels) demonstrated that both RDS and ROM-1 proteins were pulled down using anti-RDS-CT (arrow) antibodies and that rhodopsin was pulled down using mAb 1D4 (arrowhead). No palmitoylated RDS or ROM-1 was detected based on the absence of a band on the [3H]-palmitate autoradiograph (Fig. 5a, right panel) corresponding to the size of RDS/ROM-1 (about 37 kDa, arrowheads). Consistent with previous reports, palmitoylated rhodopsin was detected (Fig. 5b, right panel) [54].

Fig. 5.

RDS and ROM-1 are not palmitoylated. Retinas from P30 mice were isolated and incubated for 12 h with [3H]-palmitate. Retinal lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated using antibodies for the C-terminus of RDS (RDS-CT) (a) or rhodopsin (mAb 1D4) (b). Immunoprecipitants were separated by reducing SDS-PAGE and subsequently analyzed by western blotting and autoradiography. a Although immunoprecipitation using RDS-CT antibodies pulls down both RDS and ROM-1 (arrow), no palmitoylated band is detected by autoradiography. b Rhodopsin (immunoprecipitated with mAb 1D4, arrowhead) is palmitoylated consistent with previous reports. This experiment was repeated independently three times with different preparations

The lack of detection of palmitoylated RDS suggests that this protein is either not palmitoylated or is palmitoylated at very low levels. C82 is conserved among RDS family members, but C105 is not, and neither is it reported to be associated with retinal disease (http://www.retina-international.org/sci-news/rdsmut.htm). Coupled with the lack of detected ROM-1 palmitoylation and the lack of proximal membrane cysteines in ROM-1, these data suggest that RDS and ROM-1 diverge from traditional tetraspanins with regard to palmitoylation. The significance of this divergence is unknown, but several possible explanations exist. The simplest is that RDS forms a different type of TEM from other tetraspanins. RDS function may not require it to interact with palmitoylation-dependent binding partners, such as integrins, which are common among other tetraspanins. In fact, absence of RDS palmitoylation may help ensure that RDS does not make abnormal associations with some of the more common tetraspanin binding partners which could adversely affect its proper localization and unique complex assembly. Palmitoylation of tetraspanins often functions to enhance the formation of loose secondary protein associations. If RDS were palmitoylated, formation of these loose secondary interactions could impair the formation of the tight, covalently bound RDS complexes. In addition, it is possible that as a result of the quaternary structure of RDS/ROM-1 tetrameric and higher order oligomeric complexes, potential RDS palmitoylation sites are unavailable and that artificially induced palmitoylation might destabilize RDS/ROM-1 complexes.

Glycosylation

N-glycosylation sites are not highly conserved in location or number among different members of the tetraspanin family [1]. Glycosylation has been implicated as a determinant of protein interactions in tetraspanins on a protein-by-protein basis [2]. For example, the glycosylation of CD82 has a dramatic effect on its association with integrin receptors. All three CD82 glycosylation sites are in EC2, and complete glycosylation of this tetraspanin inhibits its ability to associate with α3 or α5 integrin [55]. Functionally, cells expressing glycosylation-deficient CD82 exhibit α5-mediated alterations in cell motility [55]. In spite of the functional role glycosylation plays in the case of CD82, many tetraspanins are not glycosylated, including CD9 which also binds with α3 and α5 integrins [56].

RDS is glycosylated only at N229 in EC2, although there is a second poorly conserved and nonglycosylated N-glycosylation motif in EC1 (D1) [51, 57, 58]. The glycosylation motif at position 229–231 (N–N–S) is highly conserved among all known RDS orthologues, with skate RDS being the only orthologous protein with an N–S–S glycosylation motif at that location. In spite of the other structural similarities between the two proteins, ROM-1 lacks an N-X-S glycosylation motif in EC2 [59, 60]. The most intriguing feature of the N229 glycosylation of RDS, given its high level of conservation, is that no discernible function for it has been elucidated. Kedzierski et al. investigated the possible role of RDS glycosylation in vivo by generating a transgenic mouse line expressing nonglycosylated S231A-RDS under the control of a 6.5-kb fragment of the rhodopsin promoter [57]. Their results indicated that nonglycosylated transgenic protein is biochemically and functionally similar to wild-type RDS [57]. Nonglycosylated RDS is able to form homodimers and interact with ROM-1 to produce heteromeric complexes [51, 57]. When expressed in the rds −/− background, the nonglycosylated RDS is able to independently promote elaboration of OSs [57]. These results suggest that N-glycosylation plays no significant role in RDS function. However, it is possible that the functional role for glycosylation is cell-specific. Rods and cones have a differential requirement for RDS [61] and the study on S231A-RDS used a rod-specific promoter [57], so the role of RDS glycosylation in cones has not yet been evaluated.

Phosphorylation

Tetraspanins have been shown to be important for organizing proteins that are phosphorylated [62]. However, consistent with their role as structural/organizational proteins as opposed to signaling proteins, there is no precedent for phosphorylation of tetraspanins themselves. In spite of this, there is some evidence that RDS may be phosphorylated.

Early [31P]-NMR studies suggested that a protein with similar electrophoretic mobility to RDS might be phosphorylated [63], but due to the overwhelming quantity of phosphorylated rhodopsin in OS preparations, phosphorylation of other proteins was difficult to evaluate. Subsequent studies in which RDS was purified from intact bovine rod OS preparations which had been incubated with [γ-32P]-labeled ATP showed that RDS is phosphorylated in a two to one molar ratio [22]. Phosphorylated RDS was detected by autoradiography and by probing with phosphoserine antibodies, but was only detected when the rod OS preparations were exposed to light [22]. The only cytosolic serine residues are within the C-terminal region of RDS and therefore it is hypothesized that phosphorylation occurs in this area [22]. In lipid mixing assays, light-exposed rod OS membrane preparations exhibited higher rates of membrane fusion than those not exposed to light, but it was not possible to conclusively attribute this difference to RDS phosphorylation due to the abundance of other light-sensitive and phosphorylated proteins present in the assay [22]. These results suggest that phosphorylation could be another regulator (in addition to the protein binding discussed above) of RDS-mediated fusion, but no further investigations have been undertaken and RDS phosphorylation remains a controversial issue.

Conclusions

Here we have highlighted significant similarities between RDS, ROM-1, and other members of the tetraspanin superfamily. Of particular interest is the high degree of structural conservation in EC2 among tetraspanin family members including RDS. However, in addition to these similarities RDS exhibits differences in complex assembly, post-translational modifications, and trafficking compared to other superfamily members. A key feature of tetraspanins is how much their function can vary from cell to cell based on the presence or absence of additional binding partners in the TEM. Reference to the body of tetraspanin literature significantly enhances our ability to further study divergent requirements for RDS in rods and cones and understand the pathobiology of RDS-associated retinal disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Martin Hemler for his comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [EY10609 (MIN), EY018656 (MIN), and EY018512 (SMC)], Core Grant for Vision Research EY12190, the Foundation Fighting Blindness (MIN).

References

- 1.Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Tetraspanins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58(9):1189–1205. doi: 10.1007/PL00000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemler ME. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(10):801–811. doi: 10.1038/nrm1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanez-Mo M, Barreiro O, Gordon-Alonso M, Sala-Valdes M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Tetraspanin-enriched microdomains: a functional unit in cell plasma membranes. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(9):434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stipp CS, Kolesnikova TV, Hemler ME. EWI-2 regulates alpha3beta1 integrin-dependent cell functions on laminin-5. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(5):1167–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Y, Finnemann SC. Tetraspanin CD81 is required for the alpha v beta5-integrin-dependent particle-binding step of RPE phagocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 17):3053–3063. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemler ME. Specific tetraspanin functions. J Cell Biol. 2001;155(7):1103–1107. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziyyat A, Rubinstein E, Monier-Gavelle F, Barraud V, Kulski O, Prenant M, Boucheix C, Bomsel M, Wolf JP. CD9 controls the formation of clusters that contain tetraspanins and the integrin alpha 6 beta 1, which are involved in human and mouse gamete fusion. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 3):416–424. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charrin S, Manie S, Billard M, Ashman L, Gerlier D, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Multiple levels of interactions within the tetraspanin web. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304(1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00545-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farjo R, Naash MI. The role of rds in outer segment morphogenesis and human retinal disease. Ophthalmic Genet. 2006;27(4):117–122. doi: 10.1080/13816810600976806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caplan MJ, Kamsteeg EJ, Duffield A. Tetraspan proteins: regulators of renal structure and function. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16(4):353–358. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328177b1fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arikawa K, Molday LL, Molday RS, Williams DS. Localization of peripherin/rds in the disk membranes of cone and rod photoreceptors: relationship to disk membrane morphogenesis and retinal degeneration. J Cell Biol. 1992;116(3):659–667. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molday RS, Hicks D, Molday L. Peripherin A rim-specific membrane protein of rod outer segment discs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28(1):50–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakraborty D, Conley SM, Stuck MW, Naash MI. Differences in RDS trafficking, assembly and function in cones versus rods: insights from studies of C150S-RDS. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(24):4799–4812. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanyal S, Jansen HG. Absence of receptor outer segments in the retina of rds mutant mice. Neurosci Lett. 1981;21(1):23–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng T, Peachey NS, Li S, Goto Y, Cao Y, Naash MI. The effect of peripherin/rds haploinsufficiency on rod and cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17(21):8118–8128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08118.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkins RK, Jansen HG, Sanyal S. Development and degeneration of retina in rds mutant mice: photoreceptor abnormalities in the heterozygotes. Exp Eye Res. 1985;41(6):701–720. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(85)90179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boesze-Battaglia K, Goldberg AF. Photoreceptor renewal: a role for peripherin/rds. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;217:183–225. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(02)17015-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boesze-Battaglia K, Goldberg AF, Dispoto J, Katragadda M, Cesarone G, Albert AD. A soluble peripherin/Rds C-terminal polypeptide promotes membrane fusion and changes conformation upon membrane association. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77(4):505–514. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(03)00151-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boesze-Battaglia K, Stefano FP, Fitzgerald C, Muller-Weeks S. ROM-1 potentiates photoreceptor specific membrane fusion processes. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boesze-Battagliaa K, Stefano FP. Peripherin/rds fusogenic function correlates with subunit assembly. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75(2):227–231. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.TC Edrington, 5th, Lapointe R, Yeagle PL, Gretzula CL, Boesze-Battaglia K. Peripherin-2: an intracellular analogy to viral fusion proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46(12):3605–3613. doi: 10.1021/bi061820c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boesze-Battaglia K, Kong F, Lamba OP, Stefano FP, Williams DS. Purification and light-dependent phosphorylation of a candidate fusion protein, the photoreceptor cell peripherin/rds. Biochemistry. 1997;36(22):6835–6846. doi: 10.1021/bi9627370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boesze-Battaglia K, Song H, Sokolov M, Lillo C, Pankoski-Walker L, Gretzula C, Gallagher B, Rachel RA, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Morris F, Jacob J, Yeagle P, Williams DS, Damek-Poprawa M. The tetraspanin protein peripherin-2 forms a complex with melanoregulin, a putative membrane fusion regulator. Biochemistry. 2007;46(5):1256–1272. doi: 10.1021/bi061466i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damek-Poprawa M, Krouse J, Gretzula C, Boesze-Battaglia K. A novel tetraspanin fusion protein, peripherin-2, requires a region upstream of the fusion domain for activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):9217–9224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boesze-Battaglia K, Lamba OP, Napoli AA, Jr, Sinha S, Guo Y. Fusion between retinal rod outer segment membranes and model membranes: a role for photoreceptor peripherin/rds. Biochemistry. 1998;37(26):9477–9487. doi: 10.1021/bi980173p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinberg RH, Fisher SK, Anderson DH. Disc morphogenesis in vertebrate photoreceptors. J Comp Neurol. 1980;190(3):501–508. doi: 10.1002/cne.901900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pols MS, Klumperman J. Trafficking and function of the tetraspanin CD63. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(9):1584–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stipp CS, Kolesnikova TV, Hemler ME. Functional domains in tetraspanin proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28(2):106–112. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tam BM, Moritz OL, Papermaster DS. The C terminus of peripherin/rds participates in rod outer segment targeting and alignment of disk incisures. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(4):2027–2037. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fariss RN, Molday RS, Fisher SK, Matsumoto B. Evidence from normal and degenerating photoreceptors that two outer segment integral membrane proteins have separate transport pathways. J Comp Neurol. 1997;387(1):148–156. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971013)387:1<148::AID-CNE12>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia-Espana A, Chung PJ, Sarkar IN, Stiner E, Sun TT, Desalle R. Appearance of new tetraspanin genes during vertebrate evolution. Genomics. 2008;91(4):326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang S, Yuan S, Dong M, Su J, Yu C, Shen Y, Xie X, Yu Y, Yu X, Chen S, Zhang S, Pontarotti P, Xu A. The phylogenetic analysis of tetraspanins projects the evolution of cell-cell interactions from unicellular to multicellular organisms. Genomics. 2005;86(6):674–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vilella AJ, Severin J, Ureta-Vidal A, Heng L, Durbin R, Birney E. EnsemblCompara GeneTrees: Complete, duplication-aware phylogenetic trees in vertebrates. Genome Res. 2009;19(2):327–335. doi: 10.1101/gr.073585.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C, Ding XQ, O’Brien J, Al-Ubaidi MR, Naash MI. Molecular characterization of the skate peripherin/rds gene: relationship to its orthologues and paralogues. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(6):2433–2441. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovalenko OV, Metcalf DG, DeGrado WF, Hemler ME. Structural organization and interactions of transmembrane domains in tetraspanin proteins. BMC Struct Biol. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding XQ, Stricker HM, Naash MI. Role of the second intradiscal loop of peripherin/rds in homo and hetero associations. Biochemistry. 2005;44(12):4897–4904. doi: 10.1021/bi048414i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitadokoro K, Ponassi M, Galli G, Petracca R, Falugi F, Grandi G, Bolognesi M. Subunit association and conformational flexibility in the head subdomain of human CD81 large extracellular loop. Biol Chem. 2002;383(9):1447–1452. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seigneuret M, Delaguillaumie A, Lagaudriere-Gesbert C, Conjeaud H. Structure of the tetraspanin main extracellular domain. A partially conserved fold with a structurally variable domain insertion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(43):40055–40064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovalenko OV, Yang X, Kolesnikova TV, Hemler ME. Evidence for specific tetraspanin homodimers: inhibition of palmitoylation makes cysteine residues available for cross-linking. Biochem J. 2004;377(Pt 2):407–417. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X, Kovalenko OV, Tang W, Claas C, Stipp CS, Hemler ME. Palmitoylation supports assembly and function of integrin-tetraspanin complexes. J Cell Biol. 2004;167(6):1231–1240. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang XA, Bontrager AL, Hemler ME. Transmembrane-4 superfamily proteins associate with activated protein kinase C (PKC) and link PKC to specific beta(1) integrins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(27):25005–25013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakraborty D, Ding XQ, Fliesler SJ, Naash MI. Outer segment oligomerization of rds: evidence from mouse models and subcellular fractionation. Biochemistry. 2008;47(4):1144–1156. doi: 10.1021/bi701807c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldberg AF, Molday RS. Subunit composition of the peripherin/rds–rom-1 disk rim complex from rod photoreceptors: hydrodynamic evidence for a tetrameric quaternary structure. Biochemistry. 1996;35(19):6144–6149. doi: 10.1021/bi960259n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldberg AF, Loewen CJ, Molday RS. Cysteine residues of photoreceptor peripherin/rds: role in subunit assembly and autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Biochemistry. 1998;37(2):680–685. doi: 10.1021/bi972036i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chakraborty D, Ding XQ, Conley SM, Fliesler SJ, Naash MI. Differential requirements for retinal degeneration slow intermolecular disulfide-linked oligomerization in rods versus cones. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(5):797–808. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clarke G, Goldberg AF, Vidgen D, Collins L, Ploder L, Schwarz L, Molday LL, Rossant J, Szel A, Molday RS, Birch DG, McInnes RR. Rom-1 is required for rod photoreceptor viability and the regulation of disk morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):67–73. doi: 10.1038/75621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poetsch A, Molday LL, Molday RS. The cGMP-gated channel and related glutamic acid-rich proteins interact with peripherin-2 at the rim region of rod photoreceptor disc membranes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(51):48009–48016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conley SM, Ding XQ, Naash MI. RDS in cones does not interact with the beta subunit of the cyclic nucleotide gated channel. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;664:63–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.TC Edrington, 5th, Yeagle PL, Gretzula CL, Boesze-Battaglia K. Calcium-dependent association of calmodulin with the C-terminal domain of the tetraspanin protein peripherin/rds. Biochemistry. 2007;46(12):3862–3871. doi: 10.1021/bi061999r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drummer HE, Wilson KA, Poumbourios P. Determinants of CD81 dimerization and interaction with hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328(1):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wrigley JD, Ahmed T, Nevett CL, Findlay JB. Peripherin/rds influences membrane vesicle morphology. Implications for retinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(18):13191–13194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900853199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Charrin S, Manie S, Oualid M, Billard M, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Differential stability of tetraspanin/tetraspanin interactions: role of palmitoylation. FEBS Lett. 2002;516(1–3):139–144. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Israels SJ, McMillan-Ward EM. Palmitoylation supports the association of tetraspanin CD63 with CD9 and integrin alphaIIbbeta3 in activated platelets. Thromb Res. 2010;125(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mustafi D, Palczewski K. Topology of class A G protein-coupled receptors: insights gained from crystal structures of rhodopsins, adrenergic and adenosine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75(1):1–12. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.051938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ono M, Handa K, Withers DA, Hakomori S. Glycosylation effect on membrane domain (GEM) involved in cell adhesion and motility: a preliminary note on functional alpha3, alpha5-CD82 glycosylation complex in ldlD 14 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279(3):744–750. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hakomori SSI. Inaugural article: the glycosynapse. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(1):225–232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012540899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kedzierski W, Bok D, Travis GH. Transgenic analysis of rds/peripherin N-glycosylation: effect on dimerization, interaction with rom1, and rescue of the rds null phenotype. J Neurochem. 1999;72(1):430–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wrigley JD, Nevett CL, Findlay JB. Topological analysis of peripherin/rds and abnormal glycosylation of the pathogenic Pro216–>Leu mutation. Biochem J. 2002;368(Pt 2):649–655. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bascom RA, Manara S, Collins L, Molday RS, Kalnins VI, McInnes RR. Cloning of the cDNA for a novel photoreceptor membrane protein (rom-1) identifies a disk rim protein family implicated in human retinopathies. Neuron. 1992;8(6):1171–1184. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moritz OL, Molday RS. Molecular cloning, membrane topology, and localization of bovine rom-1 in rod and cone photoreceptor cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(2):352–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farjo R, Skaggs JS, Nagel BA, Quiambao AB, Nash ZA, Fliesler SJ, Naash MI. Retention of function without normal disc morphogenesis occurs in cone but not rod photoreceptors. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(1):59–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Franco M, Muratori C, Corso S, Tenaglia E, Bertotti A, Capparuccia L, Trusolino L, Comoglio PM, Tamagnone L. The tetraspanin CD151 is required for met-dependent signaling and tumor cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(50):38756–38764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boesze-Battaglia K, Albert AD, Frye JS, Yeagle PL. Differential membrane protein phosphorylation in bovine retinal rod outer segment disk membranes as a function of disk age. Biosci Rep. 1996;16(4):289–297. doi: 10.1007/BF01855013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]