Abstract

Context:

Yoga is an ancient science, which originated in India. Pranayama has been assigned a very important role in yogic system of exercises. It is known that regular practice of breathing exercises (pranayama) increases parasympathetic tone, decreases sympathetic activity, and improves cardiovascular functions. Different types of breathing exercises alter autonomic balance for good by either decrease in sympathetic or increase in parasympathetic activity. Mukh Bhastrika (yogic bellows), a type of pranayama breathing when practiced alone, has demonstrated increase in sympathetic activity and load on heart, but when practiced along with other types of pranayama has showed improved cardiac performance.

Aim:

The present study was conducted to evaluate the effect of long term practice of fast pranayama (Mukh Bhastrika) on autonomic balance on individuals with stable cardiac function.

Settings and Design:

This interventional study was conducted in the department of physiology.

Materials and Methods:

50 healthy male subjects of 18 - 25 years age group, fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria underwent Mukh Bhastrika training for 12 weeks. Cardiovascular autonomic reactivity tests were performed before and after the training.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The parameters were analyzed by Student t test.

Results:

This study showed an increase in parasympathetic activity i.e., reduced basal heart rate, increase in valsalva ratio and deep breathing difference in heart rate; and reduction in sympathetic activity i.e., reduction in fall of systolic blood pressure on posture variation.

Conclusion:

It can be concluded that Mukh Bhastrika has beneficial effect on cardiac autonomic reactivity, if practiced for a longer duration.

Keywords: Cardiovascular autonomic reactivity, Mukh Bhastrika, valsalva ratio, yogic bellows

INTRODUCTION

Yoga is an ancient science, which originated in India.[1] Yoga includes diverse practices such as physical postures (asanas), regulated breathing (pranayama), meditation and lectures on philosophical aspects of yoga.[2] Pranayama has been assigned a very important role in yogic system of exercises and is said to be much more important than yogasanas for keeping a sound health.[3] With increased awareness and interest in health and natural remedies, yogic techniques including pranayamas are gaining importance and are becoming acceptable to scientific community.[4] Mukh Bhastrika, a type of pranayama breathing,[3] is a term derived from the “bellow” used by the blacksmith to keep his coal furnace alive.[5]

It is known that regular practice of breathing exercises (pranayama) increases parasympathetic tone, decreases sympathetic activity, improves cardio-vascular and respiratory functions, decreases the effect of stress and strain on the body and improves physical and mental health.[6] Yogis are capable of controlling their autonomic functions.[7] Different types of breathing exercises alter autonomic balance for good by either decreasing sympathetic or increasing parasympathetic activity.[8,9] However, previous studies on fast pranayamas,one on Bhastrika alone demonstrated increase in sympathetic activity and load on heart,[10] and only few others such as kapalbhati, similar to Bhastrika, have shown to reduce the sympathetic activity.[11] Hence, it implies that individually fast pranayamas have variable effect on cardiac autonomic balance. Hence, we designed a study to evaluate the effect of long term practice of fast pranayama, Mukh Bhastrika (yogic bellows) on autonomic balance on individuals with stable cardiac function.

In today's ever-changing, technologically advanced, and highly competitive environment, humans are exposed to persistent stress. Acute stresses improve the performance by increasing sympathetic discharge for a short time; however, chronic stress increases sympathetic discharge for a longer time, and is characterized by a change in the set point of hypothalamo pituitary axis activity, leading to immediate effects on heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, respiratory rate, plasma catecholamine and corticosteroids. Thus, sympathetic over-activity for a longer time is associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.[8] Such issues can be tackled by simple modification in life style like diet, exercise, yoga and various other relaxation techniques, as preventive as well as curative methods. One such method is practice of various types of pranayamas, the results of which can be beneficial in a similar manner, and widely applicable in day- to-day life, to all people from various social, environmental, cultural, and religious backgrounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Fifty healthy male individuals (age group 18-25 years) were studied. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institution. All the subjects had a uniform pattern of diet and activity, were not trained athletes/yoga performers, smokers, alcoholics, were not taking drugs or other forms of tobacco, and were not having any kind of cardiovascular disorders as assessed by, detailed history and thorough physical and clinical examination. Prior to participation, the potential risks and benefits of the research study were explained to all the patients, and an informed written consent was obtained from each participant.

Parameters

Before and after training the subjects for Mukh Bhastrika, the following cardiovascular autonomic reactivity tests were performed: [results of tests were expressed as ratios and differences which have been accepted by Ewing and Clarke; accepted by Ewing and Clarke[12] , and heart rate recording was done by an electrocardiogram (ECG) and blood pressure (BP) was recorded by using a portable non-invasive BP monitor (Omron Inc., japan)]

Heart rate response to valsalva manoeuvre (valsalva ratio);

Heart rate variation to deep breathing (deep breathing difference: - DBD);

Blood pressure response to standing.

Mukh Bhastrika

Mukh Bhastrika training was carried out in Yoga Centre, everyday in the morning 7 to 7.30 a.m., 5 days a week, for 12 weeks, on empty stomach. Subjects were asked not to practice any other type of yoga, pranayama or exercise and have food only in the college mess during this period.

The procedure of Mukh Bhastrika

Sit on padmasana. Keep the body, neck and head erect. Close the mouth. Inhale and exhale quickly ten times like the bellows of the blacksmith i.e.,with hissing sound. Start with rapid expulsion of breath following one another in rapid succession. After ten expulsions, the final expulsion is followed by the deepest possible inhalation. Breath is suspended as long as it can be done with comfort. Deepest possible exhalation is done very slowly. This completes one round of Bhastrika. Rest a while after one round is over by taking a few normal breaths. Start with the next round. Practice up to three rounds. After completion of Bhastrika training for 12 weeks, there were no dropouts from the training session. The subjects were again subjected to the tests described above, individually.

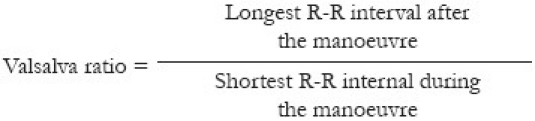

Valsalva ratio

Valsalva ratio is a measure of change of heart rate that takes place during a period of forced expiration against a closed glottis or mouth piece (valsalva manoeuvre). The subject was allowed to sit in erect posture in a chair with rubber clip over the nose; and, resting ECG was recorded for fifteen seconds in lead II. Later, the subject was asked to blow the mercury manometer up to 40 mm Hg and maintain the mercury column there (that is, at 40 mm Hg) for fifteen seconds, by continued blowing into the mouth piece connected to mercury sphygmomanometer. A continuous electrocardiogram recording was done during and fifteen seconds following the manoeuvre. The result was expressed as the valsalva ratio derived from the following formula-

For every subject, such three recordings of valsalva ratio were derived. The highest among the three was considered for further analysis.

A valsalva ratio of:

1.21 or greater – taken as normal

1.11 to 1.20 – as borderline.

1.10 or less – was taken as an abnormal response.

(This is a test for the parasympathetic system functioning.)

Heart rate response to deep breathing (deep breathing difference, DBD)

The subject in sitting position was asked to breathe quietly and deeply at a rate of six breaths per minute (five seconds in and five seconds out for every breath). An ECG was recorded throughout the period of deep breathing. The onset of inspiration and expiration was marked. The maximum and minimum R-R intervals were measured during expiration and inspiration respectively, and heart rate calculated as beats per minute. The difference between the maximum and minimum heart rates was calculated after taking three such recordings at an interval of five minutes between each; and, the best of the three was considered.

A difference of:

15 beats or more / minute – taken as Normal

11 to 14 beats / minute – as borderline.

10 beats or less / minute – was taken as an abnormal response

(This is a test for the parasympathetic system functioning.)

Blood pressure response to standing

Subject's BP was recorded in the upper arm with the help of sphygmomanometer when lying quietly, and again recorded immediately when he stood up. The postural fall of blood pressure was taken as difference between the systolic blood pressure on lying down and the systolic blood pressure on standing. This difference was considered after taking three recordings and using the best of the three values (erect blood pressure with least fall compared to the supine blood pressure), was considered.

A postural fall of systolic blood pressure of:

10 mm Hg or less was taken as normal.

11 – 29 mm Hg was taken as borderline.

30 mm Hg or more was taken as an abnormal response.

(This is a test for the sympathetic system functioning.)

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD). Statistical analysis was done using Student's t test. P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

The mean age (in years) of fifty male subjects was 19.48 ± 1.21, mean height (in cm) was 168.50 ± 9.57 and mean weight (in kg) was 56.88 ± 6.10. The autonomic reactivity test results are discussed below:

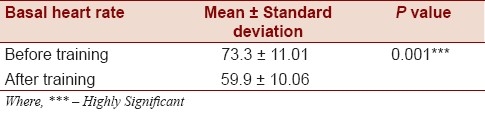

Basal pulse rate : The basal pulse rate (beats per minute) reduced from 73.3 ±11.01 to 59.9 ±10.06 after 12 weeks of Mukh Bhastrika training [Table 1].

Table 1.

Basal pulse rate before and after Mukh Bhastrika training in the participants of the study

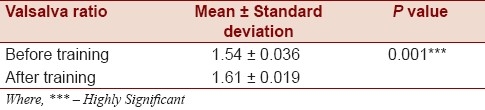

Heart rate response to valsalva manoeuvre (valsalva ratio): The valsalva ratio significantly increased from1.54 ±0.036 to 1.61 ±0.019 after Mukh Bhastrika training [Table 2].

Table 2.

Valsalva ratio before and after Mukh Bhastrika training in the participants of the study

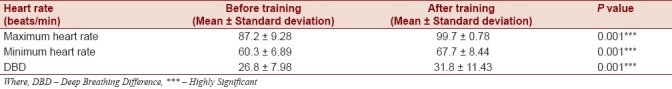

Heart rate variation to deep breathing difference (DBD): Both the maximum and the minimum heart rates achieved during deep breathing were increased after Mukh Bhastrika training compared to the control values; and, so also was the DBD in heart rates [Table 3].

Table 3.

Deep breathing difference before and after Mukh Bhastrika training in the participants of the study

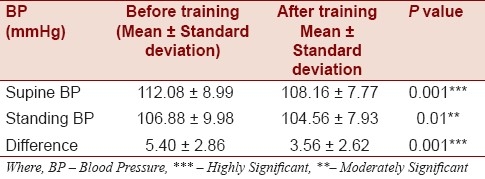

Blood pressure response to standing: The supine and standing BP reduced significantly after 12 weeks of Mukh Bhastrika training as compared to control values; and so did the postural fall in BP on standing [Table 4].

Table 4.

Postural difference in blood pressure before and after Mukh Bhastrika training in the participants of the study

DISCUSSION

The present study reveals improved cardiovascular autonomic reactivity, i.e. increase in the parasympathetic and decrease in sympathetic activity with twelve weeks of Mukh Bhastrika training. In normal resting subjects, the HR is determined mainly by background vagal activity. The basal HR is hence the function of the parasympathetic system.[13] In the present study, there was a significant decrease in basal HR indicating improvement in vagal activity/ parasympathetic tone. This finding is in accordance with another study where nadi-shodhana pranayama and savitri pranayama were included along with Mukh Bhastrika training for three months.[4] Studies on fast pranayama when practiced along with other pranayamas have shown improved cardiovascular autonomic reactivity, as found in this study with Mukh Bhastrika alone. A study on pranayama (which included nadishuddi, pranav and savitri pranayama along with Mukh Bhastrika) training for three months showed enhanced parasympathetic and reduced sympathetic activity.[4] Another study wherein pranayama included various types of pranayama along with kapalbhati (a fast Pranayama similar to Mukh Bhastrika) also showed better cardiac autonomic reactivity.[14] Yet another study on fast pranayama for three months has reported no effect on autonomic functions.[8] A study on pranayama (both fast and slow) showed an increase in vagal tone and a decrease in sympathetic activity.[6]

Very few references are available on the effect of practicing fast pranayamas on the autonomic functions in individuals. One study, wherein only Bhastrika training (three weeks) was incorporated, has reported an increase in sympathetic activity.[10] This is in contrast to the results of the present study, which may be because of longer duration of training (twelve weeks). One more study reported that practice of kapalbhati alone reduces sympathetic activity similar to the present study.[11] The explanation for the changes in autonomic activity by breathing exercises is that there are known anatomical asymmetries in the respiratory, cardiovascular and nervous system and that the coupling mechanisms between each of these systems:- lung-heart, heart-brain and lungs-brain-are also asymmetrical. These asymmetrical vector forces resulting from the mechanical activity of the lungs, heart and blood moving throughout the circulatory system, will also produce a lateralization effect in the autonomic balance. They postulate the existence of negative feedback loops between brain autonomic controls and mechanical functions in the body as a fundamental part of the body's homeostatic mechanisms. A long-term improvement in autonomic balance as well as in respiratory, cardiovascular and brain function can be achieved if mechanical forces are applied to the body with the aim of reducing existing imbalances of mechanical force vectors. This technique implies continually controlling the body functions for precise timings like in pranayamic breathing techniques.[15]

One more study has hypothesized how pranayamic breathing interacts with the nervous system affecting metabolism and autonomic functions- During inspiration, stretching of lung tissue produces inhibitory signals by action of slowly adapting stretch receptors (SARs) and hyperpolarization current by action of fibroblasts. Both the inhibitory impulses and hyperpolarization current are known to synchronize neural elements leading to the modulation of the nervous system and decreased metabolic activity indicative of the parasympathetic state.[16]

As the number of female subjects who came to practice Mukh Bhastrika pranayama was very small, it was decided to take up only male subjects inorder to make the results more reliable. Thus, it can be concluded from the present study that Mukh Bhastrika, practiced for a longer duration, has beneficial effects on the cardiovascular autonomic reactivity, and the study results can be widely applicable in day- to-day life, to all people from various social, environmental, cultural, and religious backgrounds. In conditions of chronic stress, which involves excessive sympathetic activation and thus, a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases like hypertension and coronary artery disease, practice of Mukh Bhastrika alone may be beneficial, although in this regard further studies in such affected population is essential. Also, further studies on larger sample size which includes female population, training for longer duration, and using advanced imaging technologies for evaluation can enable us to have a better understanding of underlying mechanisms and quantitative evidence of it.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vivekananda Kendra. Chennai: Vivekananda Kendra Prakashana Trust; 2005. Yoga- the science of holistic living. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagendra HR. Bangalore: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashan; 2005. Yoga its basis and application. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray S Dutta. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 1998. Yogic Exercises - Physiologic and Psychic Process. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Udupa K, Madanmohan, Bhavanani AB, Vijayalakshmi P, Krishnamurthy N. Effect of Pranayama training on cardiac function in normal young volunteers. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhavanani AB, Madanmohan, Udupa K. Acute effect of Mukh Bhastrika (a yogic bellows type breathing) on reaction time. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47:297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhargava R, Gogate MG, Mascarenhas JF. Autonomic response to breath holding and its variations following Pranayama. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;38:133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinna GS. The voluntary control of autonomic responses in yogis. Proc Int Union Physiol Sci. 1974;10:103–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pal GK, Velkumary S, Madanmohan Effect of short- term practice of breathing exercises on autonomic functions in normal human volunteers. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:115–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telles S, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. Breathing through a particular nostril can alter metabolism and autonomic activities. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;38:133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MadanMohan, Udupa K, Bhavani AB, Vijayalakshmi P, Surendiran A. Effect of slow and fast pranayama on reaction time and cardiorespiratory variables. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;49:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghuraj P, Ramakrishnan AG, Nagendra HR, Telles S. Effect of two selected yogic breathing techniques on heart rate variability. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;42:467–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewing DJ, Clarke BF. Diagnosis and management of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Br Med J. 1982;285:916–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6346.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganong WF. 20th ed. San Franscisco: Mc Graw-Hill; 2001. Review of medical physiology; pp. 575–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhimani NT, Kulkarni NB, Kowale A, Salvi S. Effect of pranayama on stress and cardiovascular autonomic tone and reactivity. Nat J Integ Res Med. 2011;2:48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullok S, Maver C, Backon J, Kullok J. Interactions between non-symmetric mechanical vector forces in the body and the autonomic nervous system: Basic requirements for any mechanical technique to engender long-term improvements in autonomic function as well as in the functional efficiency of the respiratory, cardiovascular and brain. Med Hypotheses. 1990;32:173–80. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(90)90120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jerath R, Edry JW, Branes VA, Jerath V. Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: Neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. Med Hypothesis. 2006;67:56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]