Abstract

Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) refers to the delivery of mechanical respiratory support without the use of endotracheal intubation (ETI). The present review focused on the effectiveness of NPPV in children > 1 month of age with acute respiratory failure (ARF) due to different conditions. ARF is the most common cause of cardiac arrest in children. Therefore, prompt recognition and treatment of pediatric patients with pending respiratory failure can be lifesaving. Mechanical respiratory support is a critical intervention in many cases of ARF. In recent years, NPPV has been proposed as a valuable alternative to invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in this acute setting. Recent physiological studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of NPPV in children with ARF. Several pediatric clinical studies, the majority of which were noncontrolled or case series and of small size, have suggested the effectiveness of NPPV in the treatment of ARF due to acute airway (upper or lower) obstruction or certain primary parenchymal lung disease, and in specific circumstances, such as postoperative or postextubation ARF, immunocompromised patients with ARF, or as a means to facilitate extubation. NPPV was well tolerated with rare major complications and was associated with improved gas exchange, decreased work of breathing, and ETI avoidance in 22-100% of patients. High FiO2 needs or high PaCO2 level on admission or within the first hours after starting NPPV appeared to be the best independent predictive factors for the NPPV failure in children with ARF. However, many important issues, such as the identification of the patient, the right time for NPPV application, and the appropriate setting, are still lacking. Further randomized, controlled trials that address these issues in children with ARF are recommended.

Introduction

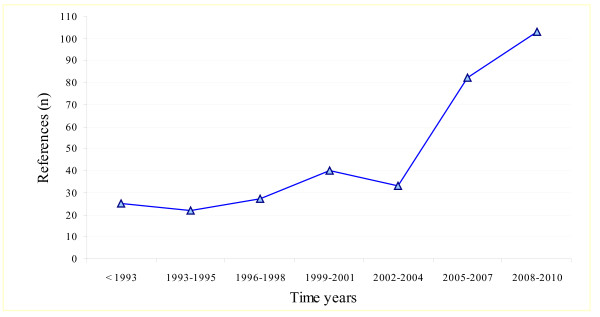

Breathing difficulties are common symptoms in children and common reason for visits to the emergency department [1]. In United Kingdom, respiratory illnesses (both acute and chronic) accounted for 20% of weekly general practitioner consultations, 15% of hospital admissions, and 8% of deaths in childhood in 2001 [2]. Although the great majority of cases are benign and self-limited, requiring no intervention, some patients will require a higher level of respiratory support. Invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) is a critical intervention in many cases of acute respiratory failure (ARF), but there are definite risks associated with endotracheal intubation (ETI) [3]. By providing respiratory support without ETI, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) may be, in appropriately selected patients, an extremely valuable alternative to IMV. It is generally much safer than IMV and has been shown to decrease resource utilization and to avoid the myriad of complications associated with ETI, including upper airway trauma, laryngeal swelling, postextubation vocal cord dysfunction, and nosocomial infections [3]. NPPV usually refers to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel respiratory support, including expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) and inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP), i.e., biphasic positive airway pressure (BIPAP) and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), delivered through nasal prongs, facemasks, or helmets. Although there is high-level evidence in the literature to support the use of NPPV for the treatment of ARF due to different causes, such as exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [4] and acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema [5] in adults, there are few reports about its use in this acute setting in children. So far, case series constitute the vast majority of the available knowledge in this age group. However, there is an increasing interest in the use of NPPV as a therapeutic tool for children with respiratory distress that is clear from the increasing number of published studies over time (Figure 1); a research of studies on the use of NPPV in children > 1 month of age, published before December 30, 2010 (database: MEDLINE via PubMed; keywords: noninvasive ventilation, non-invasive ventilation, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, bipap, continuous positive airway pressure; age limits: children from 1 month to 18 years old) identified 332 relevant articles, of which 48% were published during the past 5 years. This concise review is designed to focus on the effectiveness of NPPV in children > 1 month of age with ARF (excluding patients with neurologic or chronic lung disease).

Figure 1.

Time course of published references on noninvasive mechanical ventilation in children aged 1 month to 18 years.

Acute respiratory failure in children

The frequency of ARF is higher in infants and young children than in adults. This difference can be explained by defining anatomic compartments and their developmental differences in pediatric patients that influence susceptibility to ARF [6]. In addition, respiratory failure often precedes cardiopulmonary arrest in children, unlike in adults where primary cardiac disease often is responsible. Therefore, prompt recognition and treatment of pediatric patients with pending respiratory failure can be lifesaving [6].

Respiratory failure is a syndrome in which the respiratory system fails in one or both of its gas exchange functions: oxygenation and carbon dioxide elimination. In general, patients with respiratory failure may be classified into two groups, depending on the component of the respiratory system that is involved: hypoxemic respiratory failure and hypercapnic respiratory failure [7].

Hypoxemic respiratory failure (known as type I)

Hypoxemic respiratory failure (type I) can be associated with virtually all acute diseases of the lung, such as status asthmaticus, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary edema, which interfere with the normal function of the lung and airway. The predominant mechanism in type I failure is uneven or mismatched ventilation and perfusion (intrapulmonary shunt) in regional lung units. This is the most common form of respiratory failure, characterized by a PaO2 < 60 mmHg with a normal or low PaCO2. The primary treatment of type I respiratory failure in children is to administer supplemental oxygen at a level sufficient to increase the arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) to greater than 94%. In situations when a fraction of oxygen in inspired gas (FiO2) of greater than 0.5 is necessary to achieve this goal, this often is referred to as "acute hypoxemic respiratory failure" [7]. In this setting, NPPV may be considered.

Hypercapnic respiratory failure (known as type II)

Hypercapnic respiratory failure (type II) is a consequence of ventilatory failure and can occur in conditions that affect the respiratory pump, such as depressed neural ventilatory drive, acute or chronic upper airway obstruction, neuromuscular weakness, marked obesity, and rib-cage abnormalities. Alveolar hypoventilation is characterized by a PaCO2 > 50 mmHg [7]. The onset of type II failure may be insidious and may develop when respiratory muscle fatigue complicates preexisting disorders, such as pneumonia or status asthmaticus, which present initially with hypoxemia without hypoventilation. Aministration of oxygen alone is not an appropriate treatment for hypercapnic respiratory failure and can result in the patient retaining even more carbon dioxide, especially in situations where the child has adapted to chronic hypercapnia and is relatively dependent on oxygen-sensitive peripheral chemoreceptors to maintain ventilatory drive. In addition to supplemental oxygen, therapies to reduce the load on the respiratory muscles and increase the level of alveolar ventilation should be instituted in children with type II respiratory failure.

When to use NPPV for acute respiratory failure?

When the cause of ARF is reversible, medical treatment works to maximize lung function and reverse the precipitating cause, whereas the goal of ventilatory support is to "gain time" by unloading respiratory muscles, increasing ventilation, and thus reducing dyspnea and respiratory rate and improving gas exchange. Two recent physiological studies have demonstrated these beneficial effects of NPPV in children with ARF [8,9]. NPPV is increasingly used for treatment of ARF in children. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the studies reporting the effectiveness of NPPV in children with ARF of various etiologies [8,10-36]. However, the determinants of success of NPPV relate more prominently to the primary diagnosis as discussed below.

Table 1.

NPPV in pediatric ARF from different causes

| Study | Cause of ARF (n) | Location, Patients (n) | Age (yr) | NPPV type, Interface | Avoided ETI (%) | Other reported outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARF due to acute airway obstruction | ||||||

|

Beers et al. [10] retrospective |

Status asthmaticus | ED, 73 | 2-17a | BiPAP Nasal mask |

97 | Improved RR, SaO2 Avoided PICU admission: 22% Major complication: 0% |

|

Carroll et al. [11] retrospective |

Status asthmaticus | PICU, 5 | 9.6b | BiPAP Nasal mask |

100 | Improved RR, MPIS Major complication: 0% |

|

Needleman et al. [12] prospective, physiological |

Status asthmaticus | PICU, 15 | 8-21a | BiPAP Nasal mask |

- | Improved RR, thoracoabdominal synchrony, fractional inspired time: 80% |

|

Akingbola et al. [13] case reports |

Status asthmaticus | PICU, 3 | 9-15a | BIPAP Nasal mask |

100 | Improved RR, PaCO2, pH Major complication: 0% |

|

Till et al. [14] prospective, randomized, crossover |

Acute lower airway obstruction | PICU, 16 | 4 (0.2-14)a,c | BiPAP Nasal or facial mask |

- | Improved RR, CAS, O2 requirement Major complication: 0% |

|

Yanez et al. [15] multicentric, prospective, randomized, controlled (NPPV subgroup) |

Bronchiolitis- pneumonia (18), asthma (4), pneumonia (3) |

PICU, 25 | 1.3 (0.1-13)a,c | BIPAP, BiPAP Facial mask |

72 | Improved RR, HR, PaO2/FiO2 at 1 hr Major complication: 4% (interstitial emphysema) |

|

Thia et al. [16]d prospective, randomized, crossover |

Bronchiolitis | PICU, 29 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4)c,e | CPAP Nasal prongs |

- | Improved PaCO2 Major complication: 0% |

|

Cambonie et al. [17]d prospective, physiological |

Bronchiolitis | PICU, 12 | 0.1b | CPAP Nasal mask |

100 | Improved HR, PtcCO2 , O2 requirement, respiratory distress score, MABP at 1 hr Major complication: 0% |

| Javouhey et al. [18]d retrospective (NPPV subgroup) | Bronchiolitis | PICU, 15 | 0.1c | BiPAP, CPAP Nasal mask |

67 | Major complication: 7% (bacterial pulmonary coinfections) |

|

Larrar et al. [19]d prospective, noncontrolled (NPPV subgroup) |

Bronchiolitis | PICU, 53 | 0.1 (0.01-1)a,b | CPAP Nasal prongs |

75 | Improved RR, PaCO2 at 2 hrs Death: 0% Major complication: 0% |

|

Campion et al. [20]d,f prospective, noncontrolled (NPPV subgroup) |

Bronchiolitis-pneumonia | PICU, 69 | 0.1 (0.03-1)a,c | BIPAP, CPAP Nasal prongs, facial mask |

83 | Improved PaCO2, pH at 2 hrs Death: 0% Major complication: 0% |

|

Essouri et al. [21] prospective, randomized, controlled |

Laryngomalacia (5), tracheomalacia (3), others (2) | PICU, 10 | 0.8 (0.2-1.5)a,c | BiPAP, CPAP Nasal mask |

- | Improved RR, respiratory effort in both types of NPPV Patient-ventilator asynchrony with BiPAP |

|

Padman et al. [22]f prospective, noncontrolled (upper airway obstruction subgroup) |

Inspiratory stridor | PICU, 3 | 13b | BiPAP Nasal mask |

100 | Improved RR, HR, gas exchange, serum HCO3, dyspnea score at 72 hrs Major complication: 0% |

| ARF due to parenchymal lung disease | ||||||

|

Munoz-Bonet et al. [23]]f prospective, noncontrolled (pneumonia subgroup) |

Pneumonia | PICU, 13 | 0.2-15.8a | BIPAP Facial mask |

100 | Improved RR, HR, PaCO2, SaO2, pH, clinical score within the first 6 hrs Death: 0% Major complication: 0% |

|

Bernet et al. [24]d prospective, noncontrolled (pneumonia subgroup) |

Pneumonia | PICU, 14 | 2.4 (0.01-18)g | BIPAP, CPAP Nasal or facial mask |

50 | Improved RR, HR, PaCO2, serum HCO3 within the first 8 hrs Death: 0% |

|

Fortenberry et al. [25]f retrospective, (pneumonia subgroup) |

Pneumonia | PICU, 21 | 0.7-17a | BiPAP Nasal mask |

90 | Improved RR, PaCO2, PaO2, pH, SaO2, PaO2/FiO2 at 1 hr Death: 5% Major complication: 0% |

|

Joshi et al. [26] retrospective (primary parenchymal lung disease subgroup) |

Pneumonia, ARDS | PICU, 29 | 13c | BiPAP Facial mask |

62 | Improved RR, PaCO2, O2 requirement Major complication: 0% |

|

Essouri et al. [27] retrospective (primary parenchymal lung disease subgroup) |

CAP (23), ARDS (9), ACS (9) | PICU, 41 | 8 (0.2-16)a,b | BIPAP Nasal or facial mask |

87 (CAP) 22 (ARDS) 100 (ACS) |

Improved RR, PaCO2 at 2 hr Death: 4% (CAP), 22% (ARDS), 0% (ACS) Major complication: 0% |

|

Padman et al. [22]f prospective, noncontrolled (primary parenchymal lung disease subgroup) |

Pneumonia (13), ACS (5 episodes) | PICU, 17 | 10.6b | BiPAP Nasal mask |

85 (CAP) 80 (ACS) |

Improved RR, HR, gas exchange, serum HCO3, dyspnea score at 72 hrs Major complication: 0% |

|

Padman et al. [28] retrospective |

ACS (25 episodes) | Inpatient ward, 9 | 11.8 (4-20)a,b | BiPAP Nasal mask |

100 | Improved RR, HR, SaO2, O2 requirement Avoided PICU admission: 44% |

ACS, acute chest syndrome; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF, acute respiratory failure; BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; BIPAP, biphasic positive airway pressure; CAS, clinical asthma score; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ED, emergency department; ETI, endotracheal intubation; FiO2, fraction of oxygen in inspired gas; HR, heart rate; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; MPIS, modified pulmonary index score; NPPV, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PaCO2, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; PtcCO2, transcutaneous PCO2; RR, respiratory rate; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

aRange.

bMean.

cMedian.

dNeonatal cases also were included in the study.

eInterquartile range.

fCertain patients included in the study had underlying neurologic or chronic lung disease.

gThe numbers represent the median (range) age of the patients (n = 42) with ARF of various causes included in the study.

Table 2.

NPPV in specific circumstances

| Study | Cause of ARF (n) | Location, Patients (n) | Age (yr) | NPPV type, Interface | Avoided ETI (%) | Other reported outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPPV in postoperative ARF | ||||||

|

Stucki et al. [8]a prospective, crossover (cardiac surgery) |

Interstitial pulmonary oedema | PICU, 6 | 0.4 (0.04-0.6)b,c | BIPAP Nasal mask |

100 | Improved RR, PTPes, dPes, dyspnea score Death: 0% |

|

Bernet et al. [24]a prospective, noncontrolled (cardiac surgery subgroup) |

ND | PICU, 11 | 2.4 (0.01- 18)d |

BIPAP, CPAP Nasal or facial mask |

64 | Improved RR, HR, PaCO2, pH, serum HCO3 within the first 8 hrs Death: 0% |

|

Joshi et al. [26] retrospective (postoperative subgroup) |

Atelectasis | PICU, 16 | 12b | BiPAP Facial mask |

94 | Improved RR, PaCO2, O2 requirement, SaO2 Major complication: 0% |

|

Essouri et al. [27]a retrospective (postextubation subgroup)e |

ND | PICU, 61 | 3.2 (0.04- 15)c,f |

BIPAP Nasal or facial mask |

67 | Improved RR, PaCO2 at 2 hrs Death: 11% Major complication: 0% |

|

Kovacikova et al. [29] case reports (cardiac surgery) |

Bilateral diaphragm paralysis | PICU, 2 | 0.9-3.5c | BIPAP Facial mask, Nasopharyngeal tube |

100 | Improved RR, gas exchange Major complication: 100% (respiratory tract infection) |

|

Chin et al. [30] retrospective (liver transplantation) |

Atelectasis, hypercapnia +/-hypoxemia, pleural effusion, pneumonia |

PICU, 15 | 0.2-14c | BiPAP Nasal or facial mask |

87 | Improved PaCO2, SaO2, atelectasis Death: 13% |

| NPPV for facilitation of ventilation weaning/rescue of failed extubation (not postoperatively) | ||||||

|

Lum et al. [31]a prospective, noncontrolled (prior IMV subgroup) |

Post-extubation failure (51), weaning facilitation (98) | PICU, 149 | 0.5 (0.1- 2)b,g | BiPAP Nasal or facial mask |

75 (failure group), 86 (weaning group) | Improved RR, HR, FiO2 within the first 24 hrs Death: 5% Major complication: 11% (pneumonia) |

|

Mayordomo-Colunga et al. [32]a,h prospective, noncontrolled |

Post-extubation failure (20), weaning facilitation (21) |

PICU, 36 (41 episodes) |

1.7 (0.04- 17)b,c |

BiPAP, CPAP Nasal or facial mask, helmet |

50 (failure group), 81 (weaning group) | Death: 5% Major complication: 5% (hypercapnia), 12% (upper airway obstruction), 7% (apnea), 10% (other) |

| NPPV in immunocompromised patients | ||||||

|

Munoz-Bonet et al. [23] prospective, noncontrolled (immunocompromised subgroup) |

Pnemonia (3), ARDS (5) | PICU, 8 | 1.5-13.8c | BIPAP Facial mask |

100 (pneumonia), 40 (ARDS) |

Improved RR, HR, PaCO2, SaO2, pH, clinical score within the first 6 hrs Death: 0% Major complication: 0% |

|

Essouri et al. [27] retrospective (immunocompromised subgroup) |

ND | PICU, 12 | 8 (3-16)c,f | BIPAP Nasal or facial mask |

92 | Improved RR, PaCO2 at 2 hrs Death: 8%, Major complication: 0% |

|

Schiller et al. [33] retrospective |

Pneumonia (5), ARDS (10), pulmonary mass (1) |

PICU, 14 (16 episodes) |

13.3f | BiPAP Facial mask |

80 | Improved RR, PaO2 at 1 hr Death: 20% Major complication: 0% |

|

Piastra et al. [34] prospective, noncontrolled |

ARDS | PICU, 23 | 10.2f | BIPAP Facial mask, Helmet |

54 | Improved gas exchange at 1 hr (82%), sustained (74%) Death: 35% Major complication: 0% |

|

Desprez et al. [35] case reports |

Pneumonia (1), ARDS (1) | PICU, 2 | 13-14c | BIPAP Facial mask |

100 | Death: 0% Major complication: 50% (upper and lower digestive hemorrhage) |

|

Pancera et al. [36] retrospective (NPPV subgroup) |

ND | PICU, 120 | 9i | BIPAP Nasal mask |

74 | Death: 22.5% |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF, acute respiratory failure; BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; BIPAP, biphasic positive airway pressure; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; dPes, oesophageal inspiratory pressure swing; ETI, endotracheal intubation; HR, heart rate; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; ND, not determined; NPPV, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation; PaCO2, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PTPes, oesophageal pressure-time product; RR, respiratory rate; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

aNeonatal cases also were included in the study.

bMedian.

cRange.

dNumbers represent the median (range) age of the patients (n = 42) with ARF of various causes included in the study.

e32 patients were intubated for liver transplantation, 11 for other abdominal surgery, and 18 for respiratory distress.

fMean.

gInterquartile range.

hCertain patients included in the study had underlying neurologic disease.

iNumber represent the mean age of the patients (n = 239) included in the study, of which 120 had NPPV.

NPPV in pediatric ARF from primary respiratory disease

Acute lower airway obstruction

Lower airway disease is a common cause of ARF. Asthma accounts for the largest percentage of this group, but infections, such as viral bronchiolitis, also are common and predominantly impact the small airways. Physicians caring for acutely ill children are regularly faced with this condition. Both non-invasive and invasive ventilation may be options when medical treatment fails to prevent respiratory failure. ETI and positive pressure ventilation in children with lower airway obstruction may increase bronchoconstriction, increase the risk of airway leakage, and has disadvantageous effects on circulation and cardiac output. Therefore, ETI should be avoided unless respiratory failure is imminent despite adequate institution of all available treatment measures. NPPV can be an attractive alternative to IMV for these patients. Clinical trials in children with acute lower respiratory airway obstruction have suggested that NPPV may improve symptoms and ventilation without significant adverse events and reduce the need for IMV [10-20]. NPPV theoretically improves the respiratory status of patients with lower respiratory airway obstruction by several mechanisms [37]. During acute bronchospastic episodes, patients have an increase in airway resistance and expiratory time constant. The combination of prolonged expiratory time constant and premature closure of inflamed airways during exhalation results in dynamic hyperinflation, which causes increased positive pressure in the alveoli at end-expiration (auto-PEEP). Because the alveolar pressure must be reduced to subatmospheric levels to initiate the next breath, this auto-PEEP increases the inspiratory load and induces respiratory muscle fatigue. The EPAP delivered by NPPV may help to decrease dynamic hyperinflation by maintaining small airway patency and may reduce the patient's work of breathing by decreasing the drop in alveolar pressure needed to initiate a breath. In addition, inspiratory support, i.e., IPAP delivered by NPPV, helps to support fatigued respiratory muscles, thereby improving dyspnea and gas exchange. Needleman et al., in a physiological study, found that the NPPV use in children with status asthmaticus was associated with a decrease in respiratory rate and fractional inspired time and an improvement of thoracoabdominal synchrony in 80% of patients [12]. A few clinical studies of small size (3-73 patients) reported the use of NPPV for treatment of status asthmaticus in children (Table 1) [10,11,13,14]. NPPV was well tolerated with no major complications and was associated with an improvement of gas exchange and respiratory effort (Table 1).

Viral bronchiolitis, mainly due to respiratory syncytial virus, represents the largest cohort of children treated with NPPV [15-20]. Use of NPPV in infant with severe bronchiolitis was associated with improved respiratory rate [15,19] and PaCO2 [16,19,20], decreased work of breathing [17], and ETI avoidance in 67-100% of patients (Table 1) [17,18].

Acute upper airway obstruction

In children, dynamic upper airway obstruction can present as an acute life-threatening condition and leads to severe alveolar hypoventilation. In 2006, a survey of French PICU group found that 67% of pediatric intensivists applied frequently or systematically NPPV in the management of dynamic upper airway obstruction in children [38]. However, there is a paucity of literature on the use of NPPV in the acute setting of upper airway obstruction in children. NPPV was associated with a significant decrease in respiratory effort [21] and a sustained improvement in gas exchange [22] in children with dynamic upper airway obstruction (Table 1).

Parenchymal lung disease

The main goals of NPPV in patients with parenchymal lung disease, such as pneumonia, acute lung injury (ALI), and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), are to improve oxygenation, to unload the respiratory muscles, and to relieve dyspnea. The first goal can usually be achieved by using EPAP to recruit and stabilize previously collapsed lung tissue [39]. Unloading of the respiratory muscles during NPPV with IPAP has been reported by L'Her et al. in adult patients with ALI [39]. The authors concluded that adding IPAP to EPAP may be indispensable in patients with ALI treated with NPPV [39]. Indeed, IPAP allows a better respiratory system muscle unloading, alveolar recruitment, oxygenation, and CO2 washout improvement.

Although NPPV seems disappointing in ARF owing to pneumonia in adult patients, with failure rates of up to 66% [40], several noncontrolled trials have suggested that NPPV could improve symptoms and ventilation without significant adverse events and reduce the need for IMV in children with ARF due to pneumonia [22-27]. Use of NPPV in this acute setting in children was associated with reduction in ETI rates ranging from 50-100% (Table 1) [23,24].

The most challenging application of NPPV may be in patients with ARDS. Studies of NPPV for the treatment of ARDS in adult population have reported failure rates of 50-80% [40]. A meta-analysis of the topic in adult population concluded that NPPV was unlikely to have any significant benefit [41]. In children, the use of NPPV for the treatment of ARDS was associated with a failure rate of 78%, and 22% of them died (Table 1) [27]. Therefore, NPPV use in such a patient group is rarely justified. However, if a trial of NPPV is initiated, patients should be closely monitored and promptly intubated if their conditions deteriorate, so that inordinate delays in needed interventions are avoided.

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) is one of the leading causes of death and hospitalization among patients with sickle cell disease [42]. Approximately 70% of patients (adults or children) with ACS are hypoxic [43]. Indeed, patients with sickle cell disease are prone to infarctive crises. Thoracic bone infarction (usually in the ribs) in such patients leads to pain, splinting, hypoventilation, and the clinical signs of ACS. In situ red blood cell sickling in the lung vasculature is possibly a consequence of hypoventilation with subsequent infarction of lung parenchyma. NPPV has been proposed as a therapeutic option for patients with ACS. By improving patient oxygenation, NPPV could prevent progression from painful crisis to ACS, and ultimately to ARDS. Three retrospective studies reported favorable outcomes in children with ACS treated with NPPV (Table 1) [22,27,28].

NPPV in specific circumstances

Postoperative respiratory failure

Postoperative pulmonary complications are a major cause of morbidity, mortality, prolonged hospital stay, and increased cost of care [44]. It has been reported that 5-10% of all surgical adult patients experience postoperative pulmonary complications [45]. Atelectasis, postoperative pneumonia, ARDS, and postoperative respiratory failure have all been classified as postoperative pulmonary complications. Postoperative respiratory failure is most commonly defined as the inability to be extubated 48 hours after surgery [46], although some investigators have used 5 days [47]. NPPV has been successfully used to treat postoperative respiratory failure in both pediatric and adult patients. Compared with standard treatment, NPPV used after major abdominal surgery improved hypoxemia and reduced the need for ETI in adult population [48]. NPPV application in children with postoperative respiratory failure was associated with improved respiratory effort, gas exchange, oxygen saturation, and reduced the need for ETI (Table 1) [8,24,26,27,29,30].

Facilitation of ventilation weaning/rescue of failed extubation

The need for reintubation after failed extubation is associated with increased morbidity and high mortality [49]. NPPV has been proposed as a means of "facilitating" weaning from IMV, and as a "curative" treatment for postextubation respiratory failure. Although several studies have shown the efficacy of NPPV in weaning from IMV in adult population [50], its application for postextubation respiratory failure is not supported by randomized, controlled trials [51]. In children, two noncontrolled trials assessed the efficacy of NPPV in these settings: the application of NPPV as a means of "facilitating" ventilation weaning, and as "curative" treatment for postextubation respiratory failure was associated with success rates of 81-86% and 50-75%, respectively [31,32].

Immunocompromised children

ARF in immunocompromised patients most often results from infections, pulmonary localization of the primary disease, or even postchemotherapy cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Treatment of such patients often requires intubation and mechanical ventilation. Avoidance of the infectious complications associated with IMV is particularly attractive in these high-risk patients, in whom this could be devastating, if not fatal. Results of randomized, controlled trials have proven the beneficial effects of NPPV in immunocompromised adult patients [52,53]. Some case series reported the use of NPPV in the treatment of respiratory failure in immunocompromised children (Table 2) [23,27,33-36]. The likelihood of NPPV success in immunocompromised children seems to be related rather to the type of pulmonary disease: the ETI avoidance rates varied from 40% for ARDS to 100% for pneumonia (Table 2).

Are there predictive factors of NPPV failure in children with ARF?

It is not always apparent which patients will initially benefit from NPPV; some patients do not obtain adequate ventilation with NPPV. The NPPV failure rate may be fairly consistent for certain diseases, and NPPV failure eventually requires intubation. Inability to early identify patients who will fail NPPV can cause inappropriate delay of intubation, which can cause clinical deterioration and increase morbidity and mortality. Knowing the predictors of NPPV failure in patient with ARF is therefore crucial in deciding if and when to apply this ventilatory technique. Several authors have identified different predictive factors of NPPV failure in children with ARF: the results of studies are given in Table 3[20,24,26,27,31,54,55]. The best predictive factors for the NPPV failure in ARF appear to be the level of FiO2 and PaCO2 on admission or within the first hours after starting NPPV (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictive factors for the outcome of NPPV in children with ARF

| Study | Population (n) | Age (yr) | Success rate (%)a | Predictors of failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Campion et al. [20]b,c prospective noncontrolled |

Bronchiolitis (69) | 0.1 (0.03-1)d,e | 83 | Apnea Higher PaCO2 on admission Higher PRISM score at 24 hrs |

|

Bernet et al. [24]b prospective noncontrolled |

Pneumonia (14), bronchiolitis (4), postoperative ARF (11), other (13) | 2.4 (0.01-18)d,e | 57 | FiO2 > 0.8 at 1 hr |

|

Joshi et al. [26] retrospective (primary parenchymal lung disease subgroup) |

Pneumonia or ARDS (29) | 13d | 62 | Age ≤ 6 yr FiO2 > 0.6 within the first 24 hrs PaCO2 ≥ 55 mmHg within the first 24 hrs |

|

Essouri et al. [27]b retrospective |

CAP (23), ARDS (9), ACS (9), immune deficiency (12), postextubation ARF (61) | 5.3 (0.04-16)e,f | 73 | ARDS High PELOD score |

|

Lum et al. [31]b prospective noncontrolled |

Pulmonary diseases (129), postextubation ARF (149) | 0.7 (0.3-2.8)d,g | 76 | Higher FiO2 needs at start of NPPV Higher PRISM score on admission Sepsis at start of NPPV |

|

Munoz-Bonet et al. [54] prospective noncontrolled |

Pneumonia (20), ARDS (10), postextubation ARF (11), other (6) | 7.1 (0.1-16)e,f | 81 | MAP > 11.5 cm H2O FiO2 > 0.6 |

|

Mayordomo-Colunga et al. [55]b prospective noncontrolled |

Type I ARF (38), type II ARF (78) | 0.9 (0.05-14)d,e | 84 | Lower RR decrease at 1 hr and 6 hrs Higher PRISM score at start and at 1 hr Type I ARF |

ACS, acute chest syndrome; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF, acute respiratory failure; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; FiO2, fraction of oxygen in inspired gas; MAP, mean airway pressure; NPPV, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation; PaCO2, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PELOD, pediatric logistic organ dysfunction; PRISM, pediatric risk of mortality; RR, respiratory rate.

aNPPV was considered successful when endotracheal intubation was avoided.

bNeonatal cases also were included in the study.

cCertain patients included in the study had underlying neurologic or chronic lung disease.

dMedian.

eRange.

fMean.

gInterquartile range.

Conclusions

During recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the use of NPPV for children with ARF. There are some promising studies supporting its use in this acute setting. NPPV was well tolerated with rare major complications and was associated with improved gas exchange, decreased work of breathing, and decreased need for ETI. Both critical care ventilators and portable ventilators have been used for NPPV. However, the vast majority of the available knowledge in this acute setting results from noncontrolled trials and case series of small size. As such, many important issues, such as the identification of the patient, the right time for NPPV application, and the appropriate setting, are still lacking. Further randomized, controlled trials addressing these issues in children with ARF are needed to define better the patients who are likely to benefit from this alternative method of respiratory support. Also, the respective place of NPPV and high flow oxygen therapy in children with ARF due to different conditions has to be determined [56].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AN and FL contributed to query the literature and to draft the manuscript. They approved the final version.

Contributor Information

Abolfazl Najaf-Zadeh, Email: kazem.najafzadeh@yahoo.fr.

Francis Leclerc, Email: francis.leclerc@chru-lille.fr.

References

- Armon K, Stephenson T, Gabriel V, MacFaul R, Eccleston P, Werneke U, Smith S. Determining the common medical presenting problems to an accident and emergency department. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:390–392. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.5.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The burden of respiratory disease. Department of public health sciences St George's Hospital Medical School 2003. http://www.laia.ac.uk/factsheets/953.pdf

- Antonelli M, Conti G, Rocco M, Bufi M, De Blasi RA, Vivino G, Gasparetto A, Meduri GU. A comparison of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation and conventional mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:429–435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808133390703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightowler JV, Wedzicha JA, Elliott MW, Ram FS. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to treat respiratory failure resulting from exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326:185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng CL, Zhao YT, Liu QH, Fu CJ, Sun F, Ma YL, Chen YW, He QY. Meta-analysis: Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:590–600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotta AT, Wiryawan B. Respiratory emergencies in children. Respir Care. 2003;48:248–258. discussion 258-260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague WG. Noninvasive ventilation in the pediatric intensive care unit for children with acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;35:418–426. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki P, Perez MH, Scalfaro P, de Halleux Q, Vermeulen F, Cotting J. Feasibility of non-invasive pressure support ventilation in infants with respiratory failure after extubation: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1623–1627. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1536-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essouri S, Durand P, Chevret L, Haas V, Perot C, Clement A, Devictor D, Fauroux B. Physiological effects of noninvasive positive ventilation during acute moderate hypercapnic respiratory insufficiency in children. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:2248–2255. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers SL, Abramo TJ, Bracken A, Wiebe RA. Bilevel positive airway pressure in the treatment of status asthmaticus in pediatrics. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CL, Schramm CM. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for the treatment of status asthmaticus in children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96:454–459. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman J Sykes J Schroeder S Singer L Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Treatment of Pediatric Status Asthmaticus Pediatric Asthma, Allergy & Immunology 200417272–277. 10.1089/pai.2004.17.27221597304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akingbola OA, Simakajornboon N, Hadley EF Jr, Hopkins RL. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation in pediatric status asthmaticus. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2002;3:181–184. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200204000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thill PJ, McGuire JK, Baden HP, Green TP, Checchia PA. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation in children with lower airway obstruction. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:337–342. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000128670.36435.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez LJ, Yunge M, Emilfork M, Lapadula M, Alcantara A, Fernandez C, Lozano J, Contreras M, Conto L, Arevalo C. et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of noninvasive ventilation in pediatric acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:484–489. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318184989f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thia LP, McKenzie SA, Blyth TP, Minasian CC, Kozlowska WJ, Carr SB. Randomised controlled trial of nasal continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) in bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:45–47. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.091231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambonie G, Milesi C, Jaber S, Amsallem F, Barbotte E, Picaud JC, Matecki S. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure decreases respiratory muscles overload in young infants with severe acute viral bronchiolitis. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1865–1872. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javouhey E, Barats A, Richard N, Stamm D, Floret D. Non-invasive ventilation as primary ventilatory support for infants with severe bronchiolitis. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1608–1614. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrar S, Essouri S, Durand P, Chevret L, Haas V, Chabernaud JL, Leyronnas D, Devictor D. Effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure ventilation in infants with severe acute bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr. 2006;13:1397–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion A, Huvenne H, Leteurtre S, Noizet O, Binoche A, Diependaele JF, Cremer R, Fourier C, Sadik A, Leclerc F. Non-invasive ventilation in infants with severe infection presumably due to respiratory syncytial virus: feasibility and failure criteria. Arch Pediatr. 2006;13:1404–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essouri S, Nicot F, Clement A, Garabedian EN, Roger G, Lofaso F, Fauroux B. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in infants with upper airway obstruction: comparison of continuous and bilevel positive pressure. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:574–580. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padman R, Lawless ST, Kettrick RG. Noninvasive ventilation via bilevel positive airway pressure support in pediatric practice. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:169–173. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199801000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Bonet JI, Flor-Macian EM, Rosello PM, Llopis MC, Lizondo A, Lopez-Prats JL, Brines J. Noninvasive ventilation in pediatric acute respiratory failure by means of a conventional volumetric ventilator. World J Pediatr. 2010;6:323–330. doi: 10.1007/s12519-010-0211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernet V, Hug MI, Frey B. Predictive factors for the success of noninvasive mask ventilation in infants and children with acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:660–664. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000170612.16938.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, Del Toro J, Jefferson LS, Evey L, Haase D. Management of pediatric acute hypoxemic respiratory insufficiency with bilevel positive pressure (BiPAP) nasal mask ventilation. Chest. 1995;108:1059–1064. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Tobias JD. A five-year experience with the use of BiPAP in a pediatric intensive care unit population. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22:38–43. doi: 10.1177/0885066606295221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essouri S, Chevret L, Durand P, Haas V, Fauroux B, Devictor D. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation: five years of experience in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7:329–334. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000225089.21176.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padman R, Henry M. The use of bilevel positive airway pressure for the treatment of acute chest syndrome of sickle cell disease. Del Med J. 2004;76:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacikova L, Dobos D, Zahorec M. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for bilateral diaphragm paralysis after pediatric cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;8:171–172. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.187096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin K, Uemoto S, Takahashi K, Egawa H, Kasahara M, Fujimoto Y, Sumi K, Mishima M, Sullivan CE, Tanaka K. Noninvasive ventilation for pediatric patients including those under 1-year-old undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:188–195. doi: 10.1002/lt.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum LC, Abdel-Latif ME, de Bruyne JA, Nathan AM, Gan CS. Noninvasive ventilation in a tertiary pediatric intensive care unit in a middle-income country. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e7–13. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181d505f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayordomo-Colunga J, Medina A, Rey C, Concha A, Menendez S, Los Arcos M, Garcia I. Non invasive ventilation after extubation in paediatric patients: a preliminary study. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller O, Schonfeld T, Yaniv I, Stein J, Kadmon G, Nahum E. Bi-level positive airway pressure ventilation in pediatric oncology patients with acute respiratory failure. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24:383–388. doi: 10.1177/0885066609344956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piastra M, De Luca D, Pietrini D, Pulitano S, D'Arrigo S, Mancino A, Conti G. Noninvasive pressure-support ventilation in immunocompromised children with ARDS: a feasibility study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1420–1427. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desprez P, Ribstein AL, Didier C, Barats A, Scheib C, Defaix A, Lutz P, Astruc D. Non invasive ventilation for acute respiratory distress with febrile aplastic anemia. Arch Pediatr. 2009;16:750–751. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(09)74137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancera CF, Hayashi M, Fregnani JH, Negri EM, Deheinzelin D, de Camargo B. Noninvasive ventilation in immunocompromised pediatric patients: eight years of experience in a pediatric oncology intensive care unit. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:533–538. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181754198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll L. Noninvasive Ventilation for the Treatment of Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Diseases in Children. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 2009;10:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cpem.2009.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pouyau R Javouhey E Enquête de prévalence et de pratique de ventilation non invasive en aigu dans les services de réanimation pédiatrique francophone [abstract] Réanimation 200716s3221618693 [Google Scholar]

- L'Her E, Deye N, Lellouche F, Taille S, Demoule A, Fraticelli A, Mancebo J, Brochard L. Physiologic effects of noninvasive ventilation during acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1112–1118. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-226OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino N, Vagheggini G. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in the acute care setting: where are we? Eur Respir J. 2008;31:874–886. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00143507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal R, Reddy C, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. Is there a role for noninvasive ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome? A meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2006;100:2235–2238. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, Klug PP. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn CT, Buchanan GR. The acute chest syndrome of sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1999;135:416–422. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence VA, Hilsenbeck SG, Mulrow CD, Dhanda R, Sapp J, Page CP. Incidence and hospital stay for cardiac and pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:671–678. doi: 10.1007/BF02602761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DH, Weber EC, Schell MJ, Wong AB, Anderson CT, Barker SJ. Factors associated with postoperative pulmonary complications in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:276–284. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199502000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson LG, Hess KR, Coselli JS, Safi HJ, Crawford ES. A prospective study of respiratory failure after high-risk surgery on the thoracoabdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:271–282. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.30624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Money SR, Rice K, Crockett D, Becker M, Abdoh A, Wisselink W, Kazmier F, Hollier L. Risk of respiratory failure after repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Surg. 1994;168:152–155. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(94)80057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squadrone V, Coha M, Cerutti E, Schellino MM, Biolino P, Occella P, Belloni G, Vilianis G, Fiore G, Cavallo F, Ranieri VM. Continuous positive airway pressure for treatment of postoperative hypoxemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:589–595. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein SK, Ciubotaru RL, Wong JB. Effect of failed extubation on the outcome of mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1997;112:186–192. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KE, Adhikari NK, Keenan SP, Meade M. Use of non-invasive ventilation to wean critically ill adults off invasive ventilation: meta-analysis and systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338:b1574. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan SP, Powers C, McCormack DG, Block G. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation for postextubation respiratory distress: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:3238–3244. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.24.3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli M, Conti G, Bufi M, Costa MG, Lappa A, Rocco M, Gasparetto A, Meduri GU. Noninvasive ventilation for treatment of acute respiratory failure in patients undergoing solid organ transplantation: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;283:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert G, Gruson D, Vargas F, Valentino R, Gbikpi-Benissan G, Dupon M, Reiffers J, Cardinaud JP. Noninvasive ventilation in immunosuppressed patients with pulmonary infiltrates, fever, and acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:481–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Bonet JI, Flor-Macian EM, Brines J, Rosello-Millet PM, Cruz Llopis M, Lopez-Prats JL, Castillo S. Predictive factors for the outcome of noninvasive ventilation in pediatric acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:675–680. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181d8e303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayordomo-Colunga J, Medina A, Rey C, Diaz JJ, Concha A, Los Arcos M, Menendez S. Predictive factors of non invasive ventilation failure in critically ill children: a prospective epidemiological study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:527–536. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibler A, Pham TM, Dunster KR, Foster K, Barlow A, Gibbons K, Hough JL. Reduced intubation rates for infants after introduction of high-flow nasal prong oxygen delivery. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(5):847–52. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]