Abstract

Systemic and microvascular hemodynamic responses to transfusion of oxygen using functional and non-functional packed fresh red blood cells (RBCs) from hemorrhagic shock were studied in the hamster window chamber model to determine the significance of RBCs on rheological and oxygen transport properties. Moderate hemorrhagic shock was induced by arterial controlled bleeding of 50% of the blood volume, and a hypovolemic state was maintained for one hour. Volume restitution was performed by infusion of the equivalent of 2.5 units of packed cells, and the animals were followed for ninety minutes. Resuscitation study groups were non oxygen functional fresh RBCs where the hemoglobin (Hb) was converted to methemoglobin (MetHb) [MetRBC], fully oxygen functional fresh RBCs [OxyRBC] and 10% hydroxyethyl starch [HES] as a volume control solution. Measurement of systemic variables, microvascular hemodynamics and capillary perfusion were performed along the hemorrhage, hypovolemic shock and resuscitation. Final blood viscosities after the entire protocol were 3.8 cP for transfusion of RBCs and 2.9 cP for resuscitation with HES (baseline: 4.2 cP). Volume restitution with RBCs with or without oxygen carrying capacity recovered higher mean arterial pressure (MAP) than HES. Functional capillary density (FCD) was substantially higher for transfusion vs. HES, and the presence of MetHb in the fresh RBC did not change FCD or microvascular hemodynamics. Oxygen delivery and extraction were significantly lower for resuscitation with HES and MetRBC compared to OxyRBC. Incomplete re-establishment of perfusion after resuscitation with HES could also be a consequence of the inappropriate restoration of blood rheological properties which unbalance compensatory mechanisms, and appear to be independent of the reduction in oxygen carrying capacity.

Keywords: Microcirculation, hemorrhage, hemodilution, plasma expander, intravascular oxygen, methemoglobin, functional capillary density

INTRODUCTION

The results from studies investigating the effects of RBC transfusion on oxygen transport showed that transfusion of stored RBCs impaired oxygen delivery compared to fresh RBCs, and did not have a beneficial effect in terms of systemic oxygen consumption or survival 1–3. Although it is difficult to assess the functional properties of RBCs during sepsis, these observations question the efficacy of the transfusion of stored RBCs. One of the most notable biochemical changes in stored blood is the rapid decline in the level of 2,3 DPG, the major allosteric modifier of Hb oxygen affinity. Although synthesis of DPG does occur in RBCs after transfusion, it is a slow process, taking up to 24 hours to reach normal levels 4,5.

As a result of the increased affinity of the Hb, the availability of oxygen to the tissues may become limited, and this may lead to tissue hypoxia. Studies have shown that transfusion increases oxygen content, but does not augment oxygen utilization in critically ill patients, suggesting that stored blood is less efficacious than anticipated. However, it restores blood volume and blood viscosity. Furthermore, it provides rapid clinical benefits 1–3,5.

Severe hemorrhage is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after trauma 6. The persistent depression of microvascular blood flow despite successful restoration of hemodynamics has been suggested to promote multiple organ failure after hemorrhagic shock 7,8. Volume restitution with plasma expanders and autotransfusion as a response to hemorrhage dilute the blood components. In particular, the dilution of RBCs lowers oxygen carrying capacity, blood viscosity, and therefore the viscosity dependant component of peripheral vascular resistance. Although it is generally perceived that lowering peripheral vascular resistance (within limits) is beneficial, the range of this effect is not well defined. Recent studies on the physiology of hemodilution have advanced the hypothesis that the functional lower limit in the decrease of RBC concentration is mainly determined by the drop in blood viscosity rather than the reduction in oxygen carrying capacity 8,9.

The rationale for this hypothesis originates from experimental studies in hemorrhagic shock and extreme hemodilution, showing that there is a threshold of blood/plasma viscosity required to maintain microvascular perfusion and functional capillary density (FCD) in particular 10–13. A new interpretation for the decision to maintain blood volume via transfusion of blood is to maintain blood viscosity at physiological levels 14–16. Current studies have shown that if blood viscosity is severely decreased by hemodilution, microvascular functions are impaired, and tissue survival is jeopardized due to the local microscopic maldistribution of blood flow, rather than the deficit in oxygen delivery 10–12,14. According to these reports, maintenance of FCD in conditions of prolonged hemorrhagic shock differentiates between survival and non survival independent of oxygen carrying capacity and tissue pO2 10,17. Clearly, hemoglobin and oxygen carrying capacity become limited when oxygen delivery and metabolic oxygen needs are no longer maintained. Thus, the limit of intrinsic blood oxygen carrying capacity is lower than the point at which a blood transfusion is deemed necessary if the viscosity of blood remains sufficiently elevated 12,13.

The present study was carried out to show that restoration of systemic hemodynamics and microhemodynamics in moderate hemorrhagic shock is determined primarily by the restoration of blood viscosity, and secondarily by oxygen carrying capacity. To test this hypothesis, we subjected our experimental hamster model to hemorrhagic shock (50% of blood volume) and resuscitation (25% of blood volume) by transfusion of fresh RBCs with or without oxygen carrying capacity. Fresh RBCs without oxygen capacity were obtained by reacting Hb within the RBC with sodium nitrite, converting the Hb into MetHb. These findings were compared to resuscitation with oxygen functional fresh RBCs and a colloid solution of 10% hydroxyethyl starch.

METHODS

Animal Preparation

Investigations were performed in 55 – 65 g male Golden Syrian Hamsters (Charles River Laboratories, Boston, MA) fitted with a dorsal skinfold window chamber. Animal handling and care followed the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The experimental protocol was approved by the local animal care committee. The hamster window chamber model is widely used for microvascular studies in the unanesthetized state, and the complete surgical technique is described in detail elsewhere 18,19. The experimental animal was allowed at least 2 days for recovery before the preparation was assessed under the microscope for any signs of edema, bleeding, or unusual neovascularization. Animals were anesthetized again, and arterial and venous catheters filled with a heparinized saline solution (30 IU/ml) were implanted. Catheters were tunneled under the skin, exteriorized at the dorsal side of the neck, and securely attached to the window frame. The microvasculature was examined 3 to 4 days after the initial surgery and only animals with window chambers whose tissue did not present regions of low perfusion, inflammation, and edema were entered into the study 14.

Inclusion Criteria

Animals were suitable for the experiments if: 1) systemic variables were within normal range, namely, heart rate (HR) > 340 beat/min, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) > 80 mmHg, systemic Hct > 45%, and arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) > 50 mmHg; and 2) microscopic examination of the tissue in the chamber observed under a ×650 magnification did not reveal signs of edema or bleeding. Hamsters are a fossorial species with a lower arterial PO2 than other rodents due to their adaptation to the subterranean environment. However, microvascular PO2 distribution in the chamber window model is the same as in other rodents such as mice 20.

Acute hemorrhage and volume replacement protocol

Acute hemorrhage was induced by withdrawing 50% of estimated total blood volume (BV) via the carotid artery catheter within 5 min. Total BV was estimated as 7% of body weight. One hour after hemorrhage induction, animals were randomized and received a single volume infusion of 50% of the shed blood volume (25% of blood volume) of the resuscitation fluid (see experimental groups) within 10 min via the jugular vein catheter. Restoration of 25% of the blood volume does not cause hypervolemia (reinstating normovolemia) in the hamster window model, because autotransfusion (from the extravascular space) restores about half of the shed volume during the shock period. Volume restitution was performed by infusion of the equivalent to 2.5 units of packed cells. Transfusion and colloids resuscitation volume were identical. Animals did not receive any additional fluid during the experiment. Variables were recorded before hemorrhage (baseline), after hemorrhage (shock), and up to 90 min after volume replacement (resuscitation).

Experimental groups

Animals were divided at random into the following three experimental groups 50 min into the hypovolemic shock: 1) MetRBC, resuscitation was performed with fresh packed RBCs where Hb has been converted to MetHb (Hct of 84 – 88%); 2) OxyRBC, resuscitation was performed with fresh packed RBCs (Hct of 84 – 88%); 3) HES, resuscitation was performed with 10% hydroxyethyl starch (Pentaspan, B. Braum, Irvine, CA.). Table 1 lists the physical characteristics of the three study groups.

Table 1.

Properties of resuscitation materials

| Description | Hct | OxyHb | Viscosity | COP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | g/dl | cp | mmHg | ||

| HES | 10% Hydroxyethyl starch | 0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 85 |

| MetRBC | Pack fresh MetRBCs | 84 – 88 | 0.0 – 1.0 | 8.9 | 4 |

| OxyRBC | Pack fresh RBCs | 84 – 88 | 26.0 – 27.0 | 8.9 | 4 |

Shear rate of 160 s−1 at 37°C; COP, colloid osmotic pressure (COP) at 27°C.

Systemic Variables

MAP and heart rate (HR) were recorded continuously (MP 150, Biopac kSystem; Santa Barbara, CA). Hct was measured from centrifuged arterial blood samples taken in heparinized capillary tubes (25 µl, ~50% of the heparinized glass capillary tube is filled). Hb content was determined spectrophotometrically from a single drop of blood (B-Hemoglobin, Hemocue, Stockholm, Sweden).

Blood Chemistry and Biophysical Properties

Arterial blood was collected in heparinized glass capillaries (0.05 ml) and immediately analyzed for PaO2, PaCO2, base excess (BE) and pH (Blood Chemistry Analyzer 248, Bayer, Norwood, MA). The comparatively low PaO2 and high PaCO2 of these animals are a consequence of their adaptation to a fossorial environment. Blood samples for viscosity and colloid osmotic pressure measurements were quickly withdrawn from the animal into a heparinized 5 ml syringe at the end of the experiment for immediate analysis or refrigerated for next-day analysis. Viscosity was measured in a DV-II plus (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Middleboro, MA) cone/plate viscometer with a CPE-40 cone spindle at a shear rate of 160/sec. Colloid osmotic pressure was measured using a 4420 Colloid Osmometer (Wescor, Logan, UT).

Microvascular Experimental Setup

The unanesthetized animal was placed in a restraining tube with a longitudinal slit from which the window chamber protruded, then fixed to the microscopic stage of a transillumination intravital microscope (BX51WI, Olympus, New Hyde Park, NY). The animals were given 20 min to adjust to the change in the tube environment before measurements were made. The tissue image was projected onto a charge-coupled device camera (COHU 4815) connected to a videocassette recorder and viewed on a monitor. Measurements were carried out using a 40X (LUMPFL-WIR, numerical aperture 0.8, Olympus) water immersion objective. The same sites of study were followed throughout the experiment so comparisons could be made directly to baseline levels.

Functional Capillary Density (FCD)

Functional capillaries, defined as those capillary segments that have RBC transit of at least one RBC in a 45s period in 10 successive microscopic fields were assessed, totaling a region of 0.46 mm2. Each field had between two and five capillary segments with RBC flow. FCD (cm−1), i.e., total length of RBC perfused capillaries divided by the area of the microscopic field of view, was evaluated by measuring and adding the length of capillaries that had RBC transit in the field of view. The relative change in FCD from baseline levels after each intervention is indicative of the extent of capillary perfusion 16,21.

Microhemodynamics

Arteriolar and venular blood flow velocities were measured online by using the photodiode cross-correlation method 22 (Photo Diode/Velocity Tracker Model 102B, Vista Electronics, San Diego, CA). The measured centerline velocity (V) was corrected according to vessel size to obtain the mean RBC velocity 23. A video image-shearing method was used to measure vessel diameter (D) 24. Blood flow (Q) was calculated from the values measured as Q = π × V (D/2)2. Changes in arteriolar and venular diameter from baseline were used as indicators of a change in vascular tone. This calculation assumes a parabolic velocity profile and has been found to be applicable to tubes of 15 – 80 µm internal diameters and for Hcts in the range of 6 – 60% 23. Wall shear stress (WSS) was defined by WSS = WSR × η, where WSR is the wall shear rate given by 8VD−1, and η is the microvascular blood viscosity or plasma viscosity.

Microvascular pO2 distribution

High resolution non-invasive microvascular PO2 measurements were made using phosphorescence quenching microscopy (PQM) 14,25. PQM is based on the oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence emitted by albumin-bound metalloporphyrin complex after pulsed light excitation. PQM is independent of the dye concentration within the tissue and is well suited for detecting hypoxia because its decay time is inversely proportional to the PO2 level, causing the method to be more precise at low PO2s. This technique is used to measure both intravascular and extravascular PO2 since the albumin-dye complex continuously extravascates from the circulation into the interstitial tissue 14,25. Tissue PO2 was measured in tissue regions between functional capillaries. PQM allows for precise localization of the PO2 measurements without subjecting the tissue to injury. These measurements provide a detailed understanding of microvascular oxygen distribution and indicate whether oxygen is delivered to the interstitial areas.

Oxygen delivery and extraction

The microvascular methodology used in our studies allows a detailed analysis of oxygen supply in the tissue. Calculations are made using equation 1 and 2 16:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where RBCHb is the hemoglobin in RBCs [gHb/dlblood], γ is the oxygen carrying capacity of saturated hemoglobin [1.34 mlO2/gHb], SA% is the arteriolar oxygen saturation, (1 - Hct) is the fractional plasma volume [dlplasma/dlblood], α is the solubility of oxygen in plasma [3.14 × 10−3 mlO2/dlplasma mmHg], pO2 A is the arteriolar partial pressure of oxygen, A-V indicates the arteriolar/venular differences, and Q is the microvascular flow. The oxygen saturation for the hamster RBCs was published previously 17.

Preparation of RBCs containing methemoglobin

Fresh RBCs and plasma were collected from the donor animal before the start of the experiment. Blood was centrifuged, supernatant plasma was removed and stored, and RBC-buffy coat was discarded. RBCs were transferred into tubes and re-suspended in an equivalent amount of normal saline and mixed gently for 2 min with sodium nitrite (100 µl of 1 M sodium nitrite per 5 ml of RBCs). The cells were then centrifuged at 2,100 g, washed three times with 5 ml of heparinized saline and stored as packed cells at 4 °C. Blood was used within 2 hours of collection. Aliquots of these cells were tested, and only those cells with 95–100% MetHb were used. RBCs containing MetHb were resuspended in fresh plasma to produce an 84 – 88% Hct (26 – 27 g/dl). RBC manipulation (pipette, reaction and transfer) was performed in a laminar flow hood for sterility.

Data analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Data within each group were analyzed using analysis of variance for repeated measurements (ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test). When appropriate, post hoc analyses were performed with the Dunns multiple comparison test. Microhemodynamic measurements were compared to baseline levels obtained before the experimental procedure. The box-whisker plot separates the data into quartiles, with the top of the box defining the 75th percentile, the line within the box giving the median, and the bottom of the box showing the 25th percentile. The upper "whisker" defines the 95th percentile; the lower whisker, the 5th percentile. Microhemodynamic data are presented as absolute values and ratios relative to baseline values. A ratio of 1.0 signifies no change from baseline while lower and higher ratios are indicative of changes proportionally lower and higher than baseline (i.e., 1.5 would mean a 50% increase from the baseline level). The same vessels and capillary fields were followed so that direct comparisons to their baseline levels could be performed, allowing for more robust statistics for small sample populations. All statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism 4.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Changes were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Eighteen animals were entered into this study; all tolerated the entire hemorrhage shock resuscitation protocol without visible signs of discomfort. Animals were randomly assigned to the following experimental groups: HES (n = 6); MetRBC (n = 6); and OxyRBC (n = 6). Systemic and microhemodynamic data set for baseline and shock were obtained by combining data from all experimental groups.

Systemic variabless

Systemic hemodynamic and blood variables are presented in detail on Table 2. Hemorrhage reduced Hct and Hb (30 ± 1%; 9.7 ± 0.6 g/dl, 50 min after hemorrhage) from baseline (49 ± 1 %). Resuscitation by means of transfusion with packed red cell restored Hct and total Hb (MetRBC: 46 ± 2%; 14.6 ± 1.1 g/dl, OxyRBC: 47 ± 2 %; 14.8 ± 0.9 g/dl). Resuscitation with HES decreased Hct and Hb from the hemorrhagic shock level (25 ± 1%; 7.9 ± 0.6 g/dl). Transfusion of fresh RBCs where Hb was converted to MetHb before infusion introduced 6.2 ± 0.6 g/dl of MetHb in the blood, creating a condition where only 8.2 ± 0.4 g/dl of Hb is capable of binding oxygen. Blood typing and crossmatching tests are not necessary with the hamster, based on previous experience with the species; no changes in body temperature were detected during the protocol as early immune responses against inappropriate transfusion. The hamster hemorrhage model does not challenge considerable variability at its responses to shock, as observed by the consistency observed 50 min into the hypovolemic shock. Therefore, the spleen in the hamster is a minor RBC reservoir during hemorrhage and the early hypovolemic stage.

Table 2.

Laboratory Parameters

| Shock |

Resuscitation 60 min |

Resuscitation 90 min |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

50 min |

MetRBC |

OxyRBC |

HES |

MetRBC |

OxyRBC |

HES |

||

| Hct, % | 49 ± 1 | 30 ± 1† | 46 ± 2† | 47 ± 2†§ | 25 ± 1†‡ | 45 ± 2† | 46 ± 1†§ | 24 ± 1†‡ | |

| Hb, g/dl | 14.8 ± 0.6 | 9.7 ± 0.6† | 14.6 ± 1.1† | 14.8 ± 0.9†§ | 7.9 ± 0.6†‡ | 14.3 ± 0.8† | 14.7 ± 0.9†§ | 7.6 ± 0.5†‡ | |

| MetHb, g/dl | 6.2 ± 0.6†★ | 5.9 ± 0.5†★ | |||||||

| MAP, mmHg | 110 ± 7 | 39 ± 4† | 84 ± 7†★ | 94 ± 8†§ | 71 ± 7†‡ | 82 ± 7†★ | 96 ± 9†§ | 67 ± 8†‡ | |

| Heart Rate, bpm | 432 ± 35 | 453 ± 42 | 406 ± 27 | 442 ± 31§ | 387 ± 41† | 408 ± 34 | 422 ± 38§ | 378 ± 32† | |

| PaO2, mmHg | 56.4 ± 5.6 | 84.2 ± 8.0† | 75.1 ± 6.6†★ | 67.4 ± 6.7†§ | 79.6 ± 7.4† | 73.2 ± 5.2†★ | 64.8 ± 5.8†§ | 80.4 ± 6.1†‡ | |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 54.2 ± 4.2 | 37.3 ± 5.7† | 39.8 ± 3.9†★ | 45.4 ± 5.8†§ | 37.5 ± 5.7† | 41.5 ± 6.6†★ | 48.3 ± 6.4†§ | 36.4 ± 5.0† | |

| Arterial pH | 7.34 ± 0.02 | 7.29 ± 0.03† | 7.34 ± 0.02★ | 7.36 ± 0.01†§ | 7.33 ± 0.02† | 7.35 ± 0.01 | 7.35 ± 0.01§ | 7.33 ± 0.01†‡ | |

| BE, mmol/l | 3.0 ± 1.4 | −5.8 ± 2.2† | 0.1 ± 1.5† | 1.4 ± 1.3†§ | −1.9 ± 1.8† | 0.6 ± 1.5† | 1.8 ± 1.7§ | −3.1 ± 1.7†‡ | |

| Viscosity, cP | |||||||||

| Blood | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.3† | 3.8 ± 0.2†§ | 2.9 ± 0.3†‡ | |||||

| Plasma | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1†§ | 1.5 ± 0.2†‡ | |||||

| COP, mmHg | 17.8 ± 1.6 | 16.9 ± 1.3 | 17.2 ± 1.4 | 16.3 ± 0.8 | |||||

Plasma, Fresh plasma; MetRBC, Methemoglobin loaded fresh RBC; RBC, fresh RBC. Values are means ± SD. Baseline included all the animals in the study. Hct, systemic hematocrit; Hb, hemoglobin content of blood; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; PaO2, arterial partial O2 pressure; PaCO2, arterial partial pressure of CO2; BE, base excess. Shear rate of 160 s−1 at 37°C; COP, colloid osmotic pressure at 27°C. Values are means ± SD.

P<0.05 compared to baseline;

P<0.05 between OxyRBC and MetRBC;

P<0.05 between OxyRBC and HES;

P<0.05 betewen MetRBC and HES.

Hemorrhage and shock decreased MAP from 110 ± 7 mmHg to 39 ± 4 mmHg. Resuscitation with HES partially restored MAP to 71 ± 7 and 67 ± 8 mmHg, 60 and 90 min after resuscitation, respectively (P < 0.05 compared to baseline and transfused groups). Resuscitation by transfusion with packed cells for both groups, with or without oxygen carrying capacity, statistically restored MAP higher than resuscitation with HES at 60 and 90 min post transfusion. Resuscitation with fresh RBCs in which Hb was MetHb restored MAP to 84 ± 7 and 82 ± 7 mmHg, after 60 and 90 min post transfusion respectively. Similar results were obtained with oxygen functional RBC, restoring MAP to 94 ± 8 and 96 ± 9 mmHg at 60 and 90 min after transfusion, respectively. In all groups, MAP was statistically lower than at baseline. Heart rate was different from baseline after resuscitation with HES, and between fully functional RBC and HES at 60 and 90 min.

Gas laboratory variables and calculated acid base balance paralleled the restoration of MAP. Resuscitation with HES partially recovered systemic values. Transfusion with functional or oxygen inactivated RBCs consistently provided better restoration of systemic values than HES (Table 2). In the transfused groups, the changes in viscosity and flow were counteracted by changes in vascular geometry due to autoregulatory processes. Table 2 compares blood rheological properties and COP after resuscitation. Blood viscosities were statistically reduced from baseline in animals that received HES; resuscitation by transfusion restored blood viscosity. In contrast, plasma viscosities were increased by the addition of HES. Rheological properties and colloid osmotic pressures for baseline were obtained from blood of hamsters that did not undergo the shock protocol.

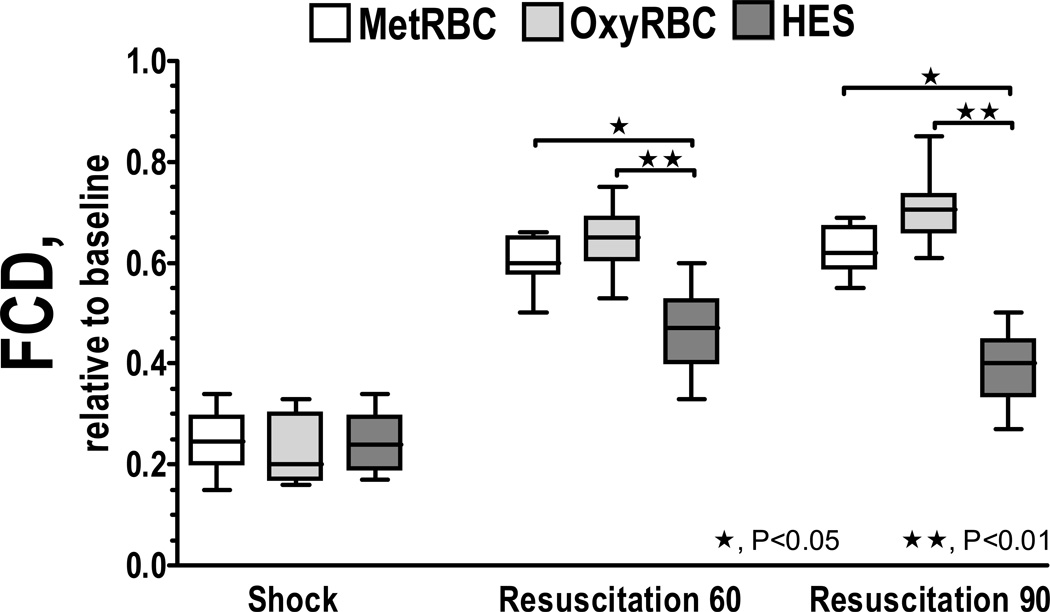

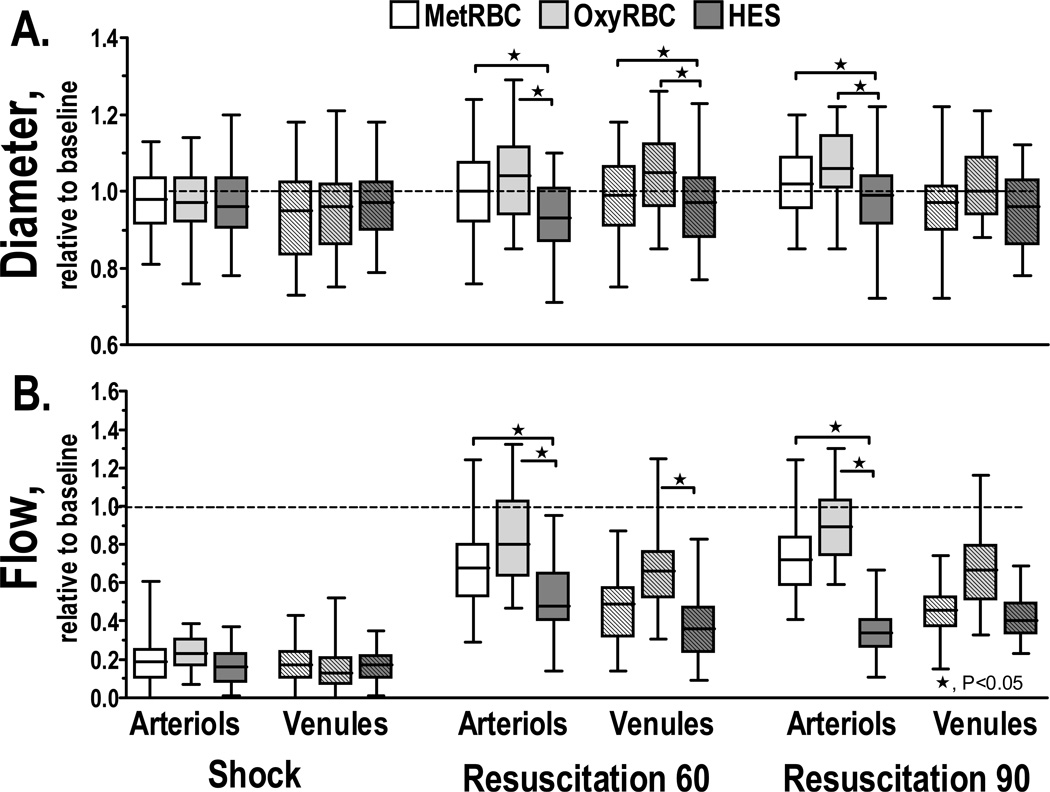

Microvascular measurements are presented in Figure 2. Arteriolar and venular diameters 60 min after resuscitation with HES were statistically decreased from transfused groups. Arteriolar and venular flows were also statistically lower for the HES group compared to the transfused groups, mostly due to vascular constriction. Surprisingly, the difference in oxygen carrying capacity among transfused groups did not produce any significant difference in vascular tone. Changes in capillary perfusion during the protocol are presented in Figure 2. FCD was significantly reduced after hemorrhage and shock. Resuscitation partially restored FCD in all groups. Differences in FCD between groups were observed at 60 min, where HES resuscitated animals were statistically lower than transfused groups. At 90 min, FCD differences among groups evidenced a more significant recovery for transfused animals with oxygen functional RBC.

Figure 2.

Effects of resuscitation on capillary perfusion during hemodilution. Functional capillary density (FCD) was drastically reduced after hemorrhage. FCD was lower after resuscitation with HES compared to volume restitution with RBCs. FCD (cm−1) at baseline was as follows: HES (107 ± 10); MetRBC (112 ± 12); and OxyRBC (105 ± 12). ★, P < 0.05 and ★★, P<0.01 among groups.

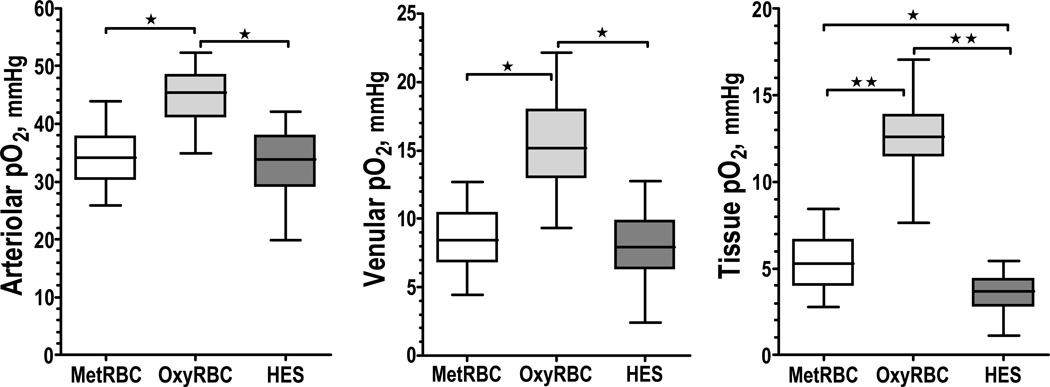

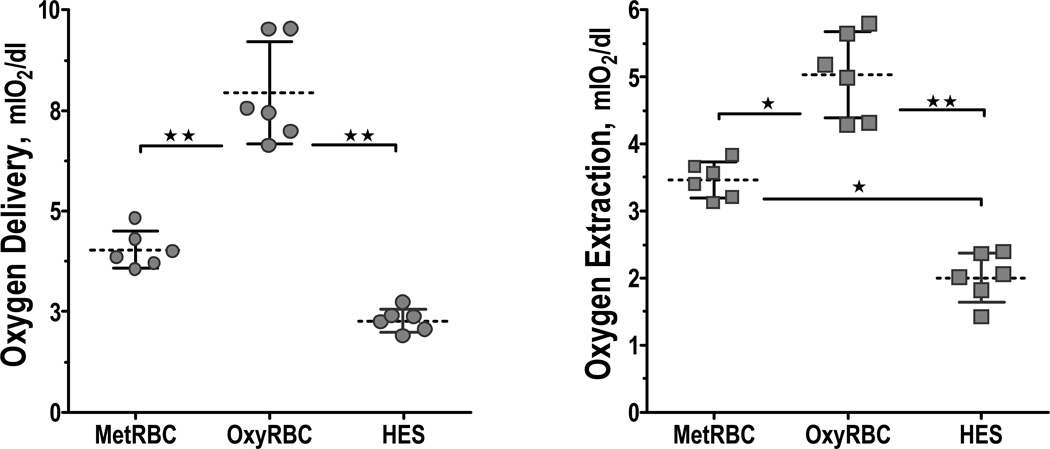

Intravascular and tissue oxygen tensions are presented in Figure 3, and differences in oxygen carrying capacity are reflected in the oxygen distribution. Restoration of perfusion in the group transfused with oxygen inactivated RBCs increased tissue PO2 compared to HES, but was lower than oxygen functional RBC. Calculated oxygen delivery and extraction are presented in Figure 4. Resuscitation with HES and with oxygen inactivated RBCs had a lower oxygen delivery and extraction compared to transfusion with oxygen functional RBCs.

Figure 3.

Microvascular oxygen partial pressure (arterioles, venules and tissue) 90 min after resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock. ★, P < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Microvascular oxygen delivery and extraction 90 min after resuscitation. ★, P<005. Calculations of global oxygen transport are not directly measurable in our model. However, the changes relative to baseline can be calculated using the measured variables. The extraction was calculated as the difference of averaged arterioles and venules for each animal. The difference in oxygen delivery and extraction between HES and MetRBC are not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study is that hemorrhagic shock resuscitation by transfusion provides superior restoration of systemic and microhemodynamic parameters when compared to simple volume restoration by means of a colloid solution. The importance of fully restored blood oxygen carrying capacity is presented by the pronounced recovery to baseline conditions after resuscitation with OxyRBC, compared with other groups. MetRBC and HES had similar oxygen carrying capacities after resuscitation, therefore the difference observed between groups are due to blood rheological properties. The initial recovery response observed after infusion of RBCs should be due to the rapid blood volume restoration complementing the autotransfusion that took place during shock. Our results suggest that the principal factor in ensuring hemodynamic restoration by RBCs besides the volume is the restoration of blood viscosity for the levels of oxygen carrying capacity loss tested in this study (decrease in intrinsic oxygen carrying capacity by 40% of baseline).

The role of blood viscosity in maintaining systemic blood pressure and blood gases are highlighted by the results obtained, since transfusion of RBCs for resuscitation, regardless of oxygen carrying capacity, provided consistent restoration of homeostasis compared to resuscitation with HES. Acid base balance post volume restitution with HES clearly presented a weak trend of recovery compared to transfusion. The beneficial effects of maintaining blood viscosity after resuscitation from hemorrhage were similar to results found using high viscosity plasma expanders to enhance blood rheological properties without adding Hct in a similar protocol 12,13.

Transfusion of RBCs provided a 25% increase in whole blood viscosity relative to resuscitation with HES. This difference may account for the increase in MAP, microvascular perfusion and FCD by restitution of shear mediated factors. Shear stress exerted by blood moving near the endothelial surface influences vessel diameter and modulates the release of dilatory autocoids (prostacyclin, nitric oxide). A previous study by Tsai et al. 26 showed in the microcirculation preparation that increased shear stress was associated with an increase in the measured concentration of perivascular nitric oxide, with concomitant vasodilator effects. Another possibility is that the viscous drag exerted is sensed via the glycocalyx, triggering the activation of endothelial mechanisms 27,28. Even in vital organs like the heart where ion channels are imperative, nonselective channels could be activated by stretching the cell membrane by fluid shear stress 28,29. Current studies show that if blood viscosity is severely decreased by blood dilution, microvascular function is impaired, and tissue survival is jeopardized due to the local microscopic maldistribution of blood flow as well as the deficit in oxygen delivery 9,14. Also in hemorrhagic shock, a limit is reached when the diluted blood is no longer able to maintain the metabolic requirements of the tissue 17.

Hamsters are adapted to a fossorial environment, and in normal conditions have low central PaO2, namely 57 mmHg, corresponding to an Hb O2 saturation of 84%. Because arteriolar pO2 is 57 mmHg (Hb O2 saturation 81%), calculation of the premicrovascular oxygen consumption shows that this species is very efficient in delivering oxygen to the tissue because very little oxygen exits the circulation before arrival at the microcirculation, with the change in blood saturation only 3%. The present experiments showed that when the oxygen supply limitation was reached, oxygen uptake in the lungs increased, raising blood PaO2 to near-normal levels in most species, 80 mmHg (Table 2). Figure 4 presents information on changes in blood flow and the intrinsic oxygen carrying capacity due to the change in OxyHb and microvascular oxygen levels. This shows that after OxyRBC resuscitation, the amount of oxygen delivery was two or three times the oxygen delivery for MetRBC or HES. However, oxygen extraction was only 45% higher for OxyRBC compared to MetRBC. Regardless of the shift in oxygen distribution, the efficiency of oxygen extraction (O2 extraction/O2 delivery) was higher after MetRBC and HES resuscitation (85.8% and 88.1%, respectively), compared to OxyRBC (63.4%). This calculation showed that in conditions of reduced oxygen carrying capacity, the organism is capable of increasing the oxygen extraction from the pool of oxygen available, subsequently the most important parameter to reestablish is the perfusion. Recovering perfusion after resuscitation will maintain oxygen supply, but most crucially will guaranty the wash out of metabolites.

Our aim was to compare two extremes of the oxygen carrying capacity function of RBCs to demonstrate how blood viscosity related to RBC concentration (Hct) affects the resuscitation process. Thus we compared fresh RBCs with maximal oxygen carrying capacity, and fresh RBCs whose Hb oxygen carrying capacity was inactivated by conversion of Hb to Met-Hb. In this scenario, both RBCs have essentially identical physical properties. We did not study the effect of RBC storage time, which in principle would show effects due to intermediate oxygen carrying capacity, as a function of the level of 2–3DPG depletion. Storage time and the preparation before storage involving repeated washing changes the physical properties of RBCs, leading to alterations that are collectively labeled as storage lesion effects, not present in fresh RBCs.

Blood conserved by conventional means for transfusion carries a limited amount of oxygen upon introduction into the circulation. Oxygen transport by transfused RBCs begins several (2 – 5) hours later 30. Consequently, a conventional blood transfusion (using stored blood) may not fully restore oxygen carrying capacity in acute conditions. However, it restores blood volume and blood viscosity. Blood transfusions have immediate subjective as well as physiological and clinical beneficial effects which are not fully explained by the restoration of oxygen carrying capacity since this occurs up to several hours later, depending on the storage period of the transfused blood. Recent studies showed that an increase in Hct in a normal organism led to a rapid increase in nitric oxide production via increased shear stress 31. Similar effects were obtained when Hct was decreased via hemodilution and plasma viscosity was increased, raising shear stress and consequently augmenting the levels of microvascular perivascular nitric oxide, producing a stable and homogeneously perfused microcirculation 26. Therefore, the beneficial effects of blood transfusion may be, in part, linked to the increase or restoration of shear stress and mechanotransduction by blood viscosity.

In conclusion, this study shows restoration of vascular homeostasis during hemorrhagic shock requires the compensation of microvascular malfunction. Compromised vital organ perfusion and consequently maldistributed oxygenation may affect survival. Restoration of volume using a fluid with rheological properties similar to those of blood appears to yield similar results as maintaining viscosity by transfusion of non oxygen functional fresh RBCs. Particularly evident in the initial period of recovery, post blood transfusions were restorations of volume maintaining viscosity, which may be a key to mending shock state. Previous studies showed that transfusions of stored RBCs, which do not necessarily raise the effective capacity of blood to transport oxygen upon transfusion, still provided beneficial effects because of the effectiveness in restoring perfusion, which is a crucial factor for oxygen delivery and flushing out metabolites produced during shock state. The restoration of blood viscosity with fresh RBC is directly linked to the increase in shear stress in the circulation, which directly influences endothelial integrity and thus permeability 32. Shear stress also promotes expression of anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, antiapoptotic and antioxidative genes 32. All these will present additional benefits in reducing the effects of systemic inflammatory conditions associated with hemorrhage.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Relative changes to baseline in arteriolar and venular hemodynamics for HES, MetRBC and OxyRBC. Broken line represents baseline level. †, P < 0.05 relative to baseline; ★, P<0.05. Diameters (µm, mean ± SD) in Figures 1A (arteriolar) and 1B (venular) for each animal group were as follows: Baseline: HES (arterioles (A): 59.1 ± 9.4, n = 42; venules (V): 59.9 ± 8.0, n = 44); MetRBC (A: 58.1 ± 9.4, n = 44; V: 56.8 ± 9.6, n = 47); OxyRBC (A: 57.9 ± 8.6, n = 43, V: 58.6 ± 8.9, n = 44). n = number of vessels studied. RBC velocities (mm/s, mean ± SD) in Figures 2C (arteriolar) and 2D (venular) for each animal group were as follows: Baseline: HES (A: 4.4 ± 1.1, V: 2.4 ± 0.8); MetRBC (A: 4.4 ± 0.9; V: 2.4 ± 0.8); OxyRBC (A: 4.5 ± 0.8; V: 2.6 ± 0.6). Calculated flows (nl/s, mean ± SD) in Figures 2E (arteriolar) and 2F (venular) for each animal group were as follows: Baseline: HES (A: 11.5 ± 3.6; V: 6.7 ± 2.3); MetRBC (A: 11.5 ± 3.1; V: 6.6 ± 2.0); OxyRBC (A: 11.0 ± 2.5; V: 6.5 ± 2.1).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Bioengineering Research Partnership grant R24-HL64395 and grants R01-HL62354, R01-HL62318 and R01-HL76182. The authors thank Froilan P. Barra and Cynthia Walser for the surgical preparation of the animals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement,

All authors do not have any financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) in their work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shah DM, Gottlieb ME, Rahm RL, et al. Failure of red blood cell transfusion to increase oxygen transport or mixed venous PO2 in injured patients. J Trauma. 1982;22:741–746. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yhap EO, Wright CB, Popovic NA, Alix EC. Decreased oxygen uptake with stored blood in the isolated hindlimb. J Appl Physiol. 1975;38:882–885. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.38.5.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purdy FR, Tweeddale MG, Merrick PM. Association of mortality with age of blood transfused in septic ICU patients. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:1256–1261. doi: 10.1007/BF03012772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valtis DJ. Defective gas-transport function of stored red blood-cells. Lancet. 1954;266:119–124. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(54)90978-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valeri CR, Hirsch NM. Restoration in vivo of erythrocyte adenosine triphosphate, 2,3, diphosphoglycerate, potassium ion, and sodium ion concentrations following the transfusion of acid-citrate-dextrose-stored human red blood cells. J Lab Clin Med. 1969;73:722–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapler CK, Cain SM, Stainsby WN. The effect of hyperoxia on oxygen uptake during acute anemia. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1984;62:809–814. doi: 10.1139/y84-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang P, Ba ZF, Burkhardt J, Chaudry IH. Measurement of hepatic blood flow after severe hemorrhage: lack of restoration despite adequate resuscitation. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:G92–G98. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.262.1.G92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messmer K, Kreimeier U. Microcirculatory therapy in shock. Resuscitation. 1989;18 Suppl:S51–S61. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(89)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrales P, Martini J, Intaglietta M, Tsai AG. Blood viscosity maintains microvascular conditions during normovolemic anemia independent of blood oxygen-carrying capacity. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:H581–H590. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01279.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerger H, Saltzman DJ, Menger MD, et al. Systemic and subcutaneous microvascular pO2 dissociation during 4-h hemorrhagic shock in conscious hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H827–H836. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.3.H827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matheson B, Kwansa HE, Bucci E, et al. Vascular response to infusions of a nonextravasating hemoglobin polymer. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1479–1486. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00191.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabrales P, Intaglietta M, Tsai AG. Increase plasma viscosity sustains microcirculation after resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock and continuous bleeding. Shock. 2005;23:549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Hyperosmotic-hyperoncotic vs. hyperosmotic-hyperviscous small volume resuscitation in hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2004;22:431–437. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000140662.72907.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai AG, Friesenecker B, McCarthy M, et al. Plasma viscosity regulates capillary perfusion during extreme hemodilution in hamster skin fold model. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H2170–H2180. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Alginate plasma expander maintains perfusion and plasma viscosity during extreme hemodilution. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:H1708–H1716. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00911.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Microvascular pressure and functional capillary density in extreme hemodilution with low and high plasma viscosity expanders. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:H363–H373. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01039.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabrales P, Nacharaju P, Manjula BN, et al. Early difference in tissue pH and microvascular hemodynamics in hemorrhagic shock resuscitation using polyethylene glycol-albumin- and hydroxyethyl starch-based plasma expanders. Shock. 2005;24:66–73. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000167111.80753.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colantuoni A, Bertuglia S, Intaglietta M. Quantitation of rhythmic diameter changes in arterial microcirculation. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:H508–H517. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.4.H508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Endrich B, Asaishi K, Götz A, Messmer K. Technical report: A new chamber technique for microvascular studies in unanaesthetized hamsters. Res Exp Med. 1980;177:125–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01851841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Frangos JA, Intaglietta M. Role of endothelial nitric oxide in microvascular oxygen delivery and consumption. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1229–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Winslow RM, Intaglietta M. Microvascular oxygen distribution in awake hamster window chamber model during hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1537–H1545. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00176.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Intaglietta M, Silverman NR, Tompkins WR. Capillary flow velocity measurements in vivo and in situ by television methods. Microvasc Res. 1975;10:165–179. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(75)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipowsky HH, Zweifach BW. Application of the "two-slit" photometric technique to the measurement of microvascular volumetric flow rates. Microvasc Res. 1978;15:93–101. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(78)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Intaglietta M, Tompkins WR. Microvascular measurements by video image shearing and splitting. Microvasc Res. 1973;5:309–312. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(73)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerger H, Groth G, Kalenka A, et al. pO2 measurements by phosphorescence quenching: characteristics and applications of an automated system. Microvasc Res. 2003;65:32–38. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(02)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai AG, Acero C, Nance PR, et al. Elevated plasma viscosity in extreme hemodilution increases perivascular nitric oxide concentration and microvascular perfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1730–H1739. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00998.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooke JP, Rossitch E, Jr, Andon NA, et al. Flow activates an endothelial potassium channel to release an endogenous nitrovasodilator. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1663–1671. doi: 10.1172/JCI115481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lansman JB, Hallam TJ, Rink TJ. Single stretch-activated ion channels in vascular endothelial cells as mechanotransducers? Nature. 1987;325:811–813. doi: 10.1038/325811a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohler R, Schonfelder G, Hopp H, et al. Stretch-activated cation channel in human umbilical vein endothelium in normal pregnancy and in preeclampsia. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1149–1156. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816080-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Intaglietta M. Microvascular perfusion upon exchange transfusion with stored RBCs in normovolemic anemic conditions. Transfusion. 2004;44:1626–1634. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martini J, Carpentier B, Chavez Negrete A, et al. Paradoxical hypotension following increased hematocrit and blood viscosity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2136–H2143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00490.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunningham KS, Gotlieb AI. The role of shear stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lab Invest. 2005;85:9–23. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.