Parathyroidectomy is the mainstay of treatment for hyperparathyroidism. Operative intervention in a previously unexplored neck can yield cure rates greater than 95% 1,2. Unfortunately, once a patient has undergone neck surgery, such as in the case of failed parathyroidectomy, reoperation leads to cure rates of only 80% 3,4. Similarly, complication rates associated with parathyroidectomy have been found to be much greater during reoperations than initial surgeries 3. The significantly lower success rate for reoperation combined with the higher complication rate, illustrates the need for a surgeon to achieve eucalcemia at the initial operation.

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is as an elevation in parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels (normal 10-65 pg/mL) causing hypercalcemia (normal 8.5-10.5 mg/dL). The symptoms of hyperparathyroidism are varied and at times vague, affecting multiple organ systems (Table 1) 5. For patients with distinct symptoms which can be attributed to the elevation in calcium levels, such as nephrolithiasis, bone disease, and cardiovascular abnormalities, surgical intervention is warranted. Many other patients with hyperparathyroidism are asymptomatic and are found to have an elevated calcium level on routine blood testing. Although these patients appear asymptomatic studies have shown that they have vague neurologic symptoms which improve with surgery 6,7. Furthermore, quality of life markedly improves in “asymptomatic patients” after parathyroidectomy 8. Similarly, data have shown that bone mass increases significantly in patients after parathyroidectomy 9. In 2009 guidelines were established for when asymptomatic patients should undergo surgery (Table 2) 10.

Table 1.

The symptoms of hyperparathyroidism are non-specific and varied, affecting multiple organ systems. Data from Doherty GM. Parathyroid Glands. In: Mulholland MW, ed. Greenfield's Surgery: Scientific Principles and Practice. Fourth ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

| SYMPTOMS OF HYPERPARATHYROIDISM |

|---|

| 1. Neurologic manifestations |

| Depression |

| Muscle weakness |

| Fatigue |

| Memory loss |

| Ataxia |

| Coma |

| 2. Gastrointestinal manifestations |

| Constipation |

| Nausea and vomiting |

| Pancreatitis |

| Peptic ulcer disease |

| 3. Renal manifestations |

| Uremia |

| Nephrolithiasis |

| 4. Cardiovascular manifestations |

| Hypertension |

| Arrhythmias |

| Coronary artery disease |

| Shortened QT interval |

| 5. Bone manifestations |

| Bone pain |

| Fractures |

Table 2.

Guidelines for surgical intervention in patients found to be hyperparathyroid, who appear to have no clinical symptoms of the disease. Data from Bilezikian J, Khan A, Potts JJ, Hyperthyroidism TIWotMoAP. Guidelines for the management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: summary statement from the third international workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Feb 2009;94(2):335-339.

| GUIDELINES FOR ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS UNDERGOING PARATHYROIDECTOMY |

|---|

| 1. Total serum calcium >1.0 mg/dL above the upper limit of normal. |

| 2. Age < 50. |

| 3. Decrease in creatinine clearance to <60 mL/min. |

| 4. Bone mineral density T score <-2.5 and/or history of fragility fracture. |

| 5. Inability to comply with annual surveillance. |

Most commonly hyperparathyroidism is due to a primary disorder of the parathyroid glands. A single parathyroid adenoma accounts for around 80% of the cases of primary hyperparathyroidism, with double adenomas and multi-gland hyperplasia making up the remaining 20% 11,12. Rarely, primary hyperparathyroidism will be the result of parathyroid carcinoma. In the United States primary hyperparathyroidism is a fairly common disease with an annual incidence of approximately 100,000 individuals 13. The incidence is increased in the elderly and in women, with 2/1000 women over 60 years of age being affected yearly 13. The mainstay of treatment for patients suffering from primary hyperparathyroidism is parathyroidecotmy.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is an excess secretion of PTH that occurs in response to hypocalcemia, most often due to chronic renal failure. It has been estimated that as many as 90% of patients with renal failure who require hemodialysis suffer from secondary hyperparathyroidism 14. Malabsorption and other disorders causing calcium and vitamin D deficiencies such as rickets and osteomalacia are less common causes of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Up to 2% of patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism will require parathyroidectomy 15.

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism occurs in those patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism due to chronic renal failure who undergo renal transplantation and continue to have persistent hyperparathyroidism. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism affects up to 30% of kidney transplant recipients and 1-5% will require surgical management 15-17.

Parathyroidectomy is the standard treatment for patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and for those with secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism requiring surgical intervention. Therefore regardless of the cause, the ability to perform a safe and successful operation is imperative for surgeons treating this population of patients.

Surgical Failure

Surgical failure for hyperparathyroidism results in persistent disease, where hypercalcemia either continues after the initial surgery or recurs within 6 months of the operation. In contrast, recurrent hyperparathyroidism occurs when a patient becomes hypercalcemic after 6 months of normal post-operative calcium levels. Although there are instances where re-operative surgery is unavoidable, for many patients their second operations are due to inadequate or inappropriate initial surgeries. Mitchell and colleagues examined this in a study on patients undergoing reoperations for thyroid and parathyroid surgery 18. They established criteria for avoidable and unavoidable parathyroid reoperations (Table 3). According to them avoidable reoperations occurred due to errors in judgment, illustrated by a surgeon performing a focal exploration or re-exploration without appropriate pre-operative localization which then leads to persistent hyperparathyroidism. Technical errors are also responsible for avoidable re-operative parathyroidectomy, such as a missed gland in its normal anatomic location. In a review of l30 patients undergoing re-operative parathyroidectomy, Udelsman and associates, reported that 91 glands were found in their normal anatomic locations 19. The remaining glands were found in the retroesophageal space, mediastinal thymus, carotid sheath, submandibular space, aortopulmonary window, or were intrathyroidal. Regardless of the location of the abnormal gland, Udelsman was able to achieve a 95% success rate, demonstrating that experienced surgeons with knowledge of the ectopic locations of parathyroid glands can perform successful parathyroidectomies and had they operated on these patients initially, a majority of reoperations could have been avoided.

Table 3.

Classification of parathyroid reoperations as either avoidable or unavoidable. Avoidable operations were either due to technical errors during the case or due to errors in judgement occurring pre-operatively or during the operation. Data from Mitchell J, Milas M, Barbosa G, Sutton J, Berber E, Siperstein A. Avoidable reoperations for thyroid and parathyroid surgery: effect of hospital volume. Surgery. Dec 2008;144(6):899-906; discussion 906-897.

| CLASSIFICATION OF PARATHYROID REOPERATIONS | |

|---|---|

| Avoidable |

Unavoidable |

| 1. Missed gland in a normal anatomic location | 1. Persistent hyperparathyroidism after appropriate pre-operative imaging and intra-operative PTH drop |

| 2. Persistent hyperparathyroidism after exploration without localization or intra-operative PTH drop | |

| 2. Persistent hyperparathyroidism due to ectopic gland not visualized on pre-operative imaging | |

| 3. Persistent hyperparathyroidism in patients with secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism or MEN syndrome after less than a subtotal parathyroidecotmy | |

| 3. Persistent hyperparathyroidism due to a supernumerary gland | |

| 4. Recurrent hyperparathyroidism | |

| 4. Re-exploration without appropriate pre-operative imaging | |

In the early nineties there began to be an increased interest in the correlation between hospital and/or surgeon volume and clinical outcomes. Several studies of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, colectomy, gastrectomy, and pancreatic resection demonstrated that high volume centers and surgeons had better outcomes than those considered to be less experienced 20-22. Similar studies have been performed by multiple authors regarding hospital and/or clinician volume as it correlates to outcomes in endocrine surgery. One of the first studies by Sosa and colleagues in 1998 demonstrated that high volume surgeons performing more than 50 parathyroidectomies yearly had significantly lower complication rates after both initial and re-operative parathyroidectomy 3. In the same study the authors also showed a significantly higher in-hospital mortality rate if parathyroidecotmy was performed by a low volume surgeon. Several years later, Stavrakis and collaborators showed a decrease in morbidity, mortality, and length of stay after thyroidectomy and parathyroidecotmy with an increase in hospital and surgeon experience 23.

More recently, researchers have begun to examine whether surgeon and hospital volume affects surgical cure rates in parathyroidectomy. In Mitchell's study, after defining avoidable and unavoidable parathyroid reoperations, they sought to determine if hospital volume correlated with the incidence of avoidable reoperations 18. They defined low volume centers as those performing less than 20 cases per year and high volume centers as greater than 20 cases annually. They examined 146 cases of re-operative parathyroidectomies and found that the low volume centers had significantly higher rates of avoidable reoperations when compared to the high volume centers (76% vs. 22%, p<0.001). Interestingly, when they compared high volume centers performing 21-50 cases per year to those performing greater than 50, they found that the high volume centers performing the fewest cases were responsible for the majority of avoidable parathyroid reoperations. These findings are supported by a paper by Chen and colleagues, where they defined preventable operative failures as those occurring due to a missed abnormal gland in a normal anatomic location 24. They defined high volume hospitals as those performing greater than 50 cases yearly and low volume centers as performing less than 50 per year. They identified 159 patients who underwent initial unsuccessful parathyroidectomy who were later cured with reoperation. Patients operated on at low volume centers were more likely to have a missed parathyroid gland in a normal anatomic location compared to those undergoing parathyroidectomy at a high volume hospital (89% vs. 13%, p<0.0001). During their follow-up all 159 patients undergoing remedial parathyroid operations were cured of their disease. These studies illustrate the importance of not only surgical experience in being able to perform a curative parathyroidectomy at the initial operation, but in having a high volume surgeon perform the reoperation.

Reoperation for hyperparathyroidism

Re-operative parathyroid surgery is technically challenging due to the presence of scar tissue, loss of previous tissue planes, and changes in normal anatomy. This not only contributes to a lower cure rate, but an increase in injuries to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and remaining parathyroid glands. To achieve a higher cure rate and lower complication rate experts in the field of endocrine surgery who perform many re-operative parathyroidectomies annually recommend adjuncts to improve outcomes. Prior to undertaking re-operative surgery, a detailed pre-operative assessment should be performed in an attempt to localize the aberrant tissue. If this is unsuccessful, several intra-operative adjuncts can aide a surgeon in executing a successful parathyroid re-operation.

Pre-operative assessment

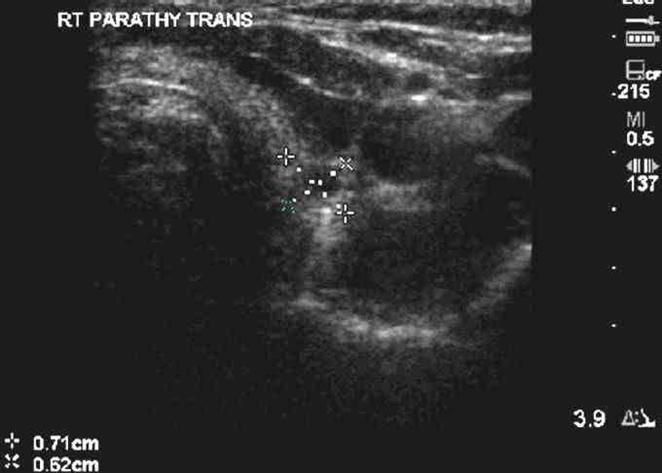

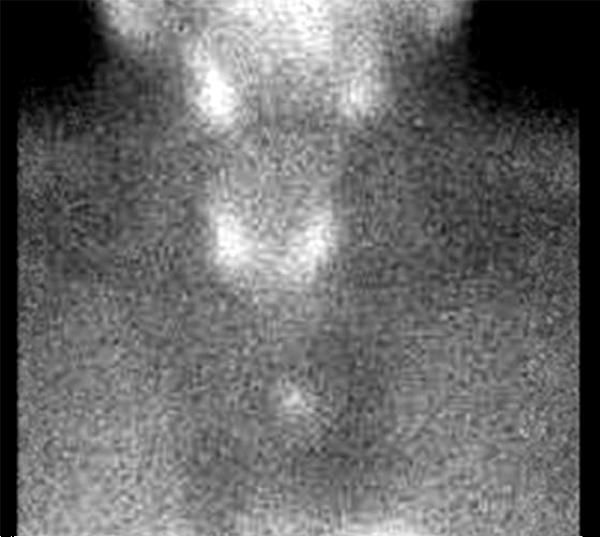

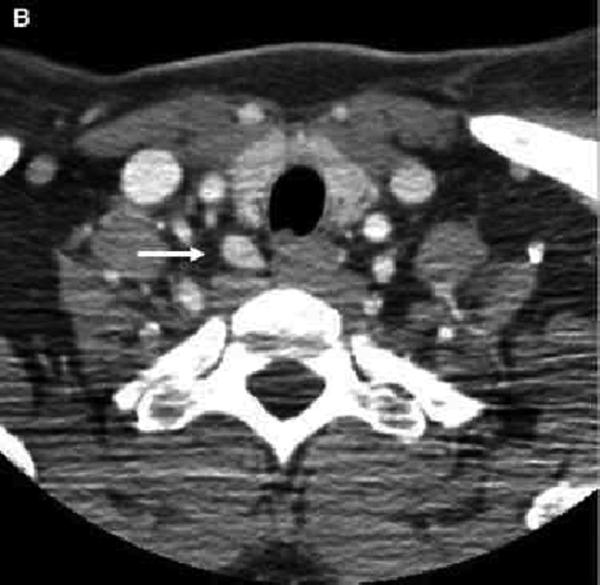

Many studies on re-operative parathyroidectomy have demonstrated improved cure rates with the utilization of various pre-operative imaging modalities (Table 4). One of the most commonly used studies is ultrasonography due to its ease of use, low cost, and non-invasive nature. Ultrasound can visualize intra-thyroidal parathyroid glands and those in the area of the carotid sheath and jugular vein, but glands which are retroesophageal or retrotracheal are difficult to localize (Figure 1). The sensitivity and positive predictive value of ultrasound varies depending on operator experience, size of the parathyroid gland, and image resolution, but have been found to be as high as 86% and 100% respectively 25,26. Sestamibi scintigraphy is another commonly used noninvasive technique for localizing parathyroid tissue and can visualize glands in ectopic locations (Figure 2). Similar to neck ultrasounds, the sensitivity and positive predictive value of sestamibi is variable, but can reach 90% and 100% respectively 25,26. For glands that can not be localized by ultrasound or sestamibi scanning, either computed tomography (CT) scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET) can be utilized. These modalities are more expensive, but may be the only method for identifying disease in the mediastinum and other ectopic locations (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Multiple non-invasive imaging techniques are available for pre-operative assessments of patients undergoing reoperations for hyperparathyroidism. In the event that the non-invasive techniques are unsuccessful, invasive modalities such as fine needle aspiration biopsy, arteriography, and venous sampling may be undertaken.

| PRE-OPERATIVE STUDIES IN RE-OPERATIVE PARATHYROIDECTOMY |

|---|

| Non-Invasive Techniques |

| Ultrasonography |

| Sestamibi scintigraphy |

| Computed tomography scan |

| Magnetic resonance imaging |

| Positron emission tomography scanning |

| Invasive Techniques |

| Fine-needle aspiration |

| Arteriography |

| Venous sampling |

Figure 1.

Neck ultrasound revealing an intrathyroidal right parathyroid gland.

Figure 2.

Sestamibi scintigraphy revealing a left inferior parathyroid gland in the mediastinum.

Figure 3.

CT scan demonstrating a right sided parathyroid adenoma in the tracheoesophageal groove. From Powell A, Alexander H, Chang R, et al. Reoperation for parathyroid adenoma: a contemporary experience. Surgery. Dec 2009;146(6):1144-1155; with permission.

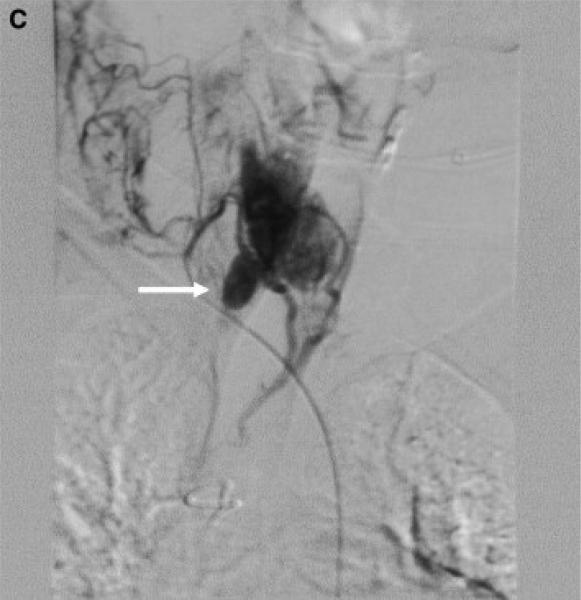

When non-invasive imaging studies are unable to localize an aberrant gland, more invasive tests need to be undertaken. If a suspicious gland if visualized on ultrasound, the diagnosis can be confirmed with fine needle aspiration biopsy. A PTH greater than 1,000 pg/mL is indicative of an abnormal gland 27. Arteriography and venous sampling can be done pre-operatively as well as in the operating room (Figure 4). These two invasive techniques are expensive and associated with complications such as arterial injuries and venous thrombosis and are therefore used less frequently than other studies.

Figure 4.

Arteriogram demonstrating a parathyroid gland in the right tracheoesophageal groove. From Powell A, Alexander H, Chang R, et al. Reoperation for parathyroid adenoma: a contemporary experience. Surgery. Dec 2009;146(6):1144-1155; with permission.

In his series of 130 patients undergoing re-operative exploration for primary hyperparathyroidism, Udelsman and colleagues described the use of multiple pre-operative imaging techniques in planning their surgeries 19. They routinely used sestamibi scanning, ultrasound, MRI, CT, venous localization, and fine needle aspiration biopsy with sensitivities of 79%, 74%, 47%, 50%, 93%, and 78% respectively. Similarly, in a study by Yen and associates, they reported their series of 39 patients undergoing reoperation for recurrent or persistent hyperparathyroidism with a success rate of 92%, higher than most published reports for re-operative parathyroidectomy 28. They advocated that all patients undergoing re-operative surgery for hyperparathyroidism should undergo both sestamibi scanning and ultrasonography of the neck. Powell and colleagues have also shown improved cure rates of 92% and a decrease in the use of invasive imaging with the use of both sestamibi and ultrasound imaging 29. In their review of 46 patients, Hessman and co-authors utilized sestamibi, PET, ultrasound, fine needle aspiration biopsy, and selective venous sampling to achieve a 98% cure rate, emphasizing that with appropriate pre-operative imaging and planning surgical cure for re-operative hyperparathyroidism is attainable.

Operative technique

Once the decision to take a patient back to the operating room has been made a surgeon has several ways to approach the operation. Many surgeons favor a medial approach through the patient's previous incision which allows for bilateral neck exploration 30. This approach can be technically difficult due to adhesions and distortion of the normal anatomy. The lateral approach is another option, which avoids the previous operative planes by dissecting lateral to the strap muscles, but in the event the abnormal parathyroid gland is not located, further dissection will be necessary. Pre-operative imaging allows for a surgeon to better plan their operative approach and at times, if the abnormal gland can not be located both a medial and lateral approach may be necessary. There are patients in whom the abnormal parathyroid gland can not be resected via a neck incision and either a median sternotomy or a transthoracic approach may be necessary to retrieve an intrathymic gland or one near the aortopulmonary window 31,32.

There are two intra-operative adjuncts available to surgeons that can improve cure rates in re-operative parathyroidectomy. Use of the intra-operative parathyroid hormone assay (IoPTH) allows for rapid identification of a fall in PTH levels after the abnormal gland is resected 2. Prior to undergoing surgical exploration, a baseline PTH value is obtained and once the abnormal gland is excised PTH values are drawn at 5, 10, and 15 minutes after excision. By definition, the PTH must fall by at least 50% from the baseline or highest value to be considered adequate 33. If a fall of 50% is not achieved then further exploration should be performed looking for another abnormal gland or for hyperplasia. The use of IoPTH in improving outcomes in initial parathyroidectomy has been reported in multiple studies 34,2. Similarly, its utilization in remedial parathyroid surgery has been shown to be equally effective. In a study from Powell and colleagues, they reported a sensitivity and specificity of IoPTH of 99% and 80% respectively, and had an overall cure rate of 92% 29. Irvin and colleagues demonstrated an improvement in their cure rates for reoperation from 76% to 94% with the introduction of IoPTH 35.

The radio-guided gamma probe is another useful intra-operative adjunct that has been shown to increase cure rates in re-operative parathyroidectomy. With this technique patients are injected with radio-labeled sestamibi 1-2 hours prior to parathyroidectomy. Background counts are obtained by placing the probe on the skin overlying the thyroid isthmus prior to incision. Once the operation is begun the probe is used to scan the field for counts greater than the initial background count. When the abnormal gland is identified and excised the ex vivo count should be greater than 20% of the background count 36,37. In a review by Cayo and colleagues they reported a case of a patient in whom pre-operative sestamibi had identified a right inferior gland, but he had previously undergone 2 failed parathyroid explorations 38. With the use of the gamma probe, they were able to locate an enlarged parathyroid gland on right directly on the spine behind the esophagus and the patient was subsequently cured. In a series of 110 patients undergoing reoperation, Pitt and associates reported a cure rate of 96% with the use of the radio-guided gamma probe 39. Concern has been raised as to whether the gamma probe is useful in the setting of a negative sestamibi scan, but Chen and colleagues were able to demonstrate utility of the radio-guided gamma probe regardless of the pre-operative sestamibi findings 40. In this study, all 769 patients had their abnormal glands localized by the gamma probe, regardless of the pre-operative sestamibi findings with a final cure rate of 98%.

More recently, with the increased use of IoPTH and the radio-guided gamma probe surgeons have been performing minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. With this approach, a small incision is made to allow for a limited dissection to resect the parathyroid gland. This approach is only recommended if pre-operative imaging has definitively identified the abnormal parathyroid tissue, but with the use of these intra-operative adjuncts success rates comparable to those of open parathyroidectomy have been reported. In their series of 656 consecutive patients, Udelsman and colleagues performed 61% of cases using the standard technique and 39% via the minimally invasive approach 1. They demonstrated an overall 98% success rate for the series with no difference between the two approaches. Similarly, Chen and associates also demonstrated a 98% success rate with the minimally invasive approach with the combination of radio-guided gamma probe and IoPTH 36.

Despite a surgeon's best efforts, there are patients in which the abnormal parathyroid gland remains unidentified. In this instance many surgeons advice performing ligation of the blood supply to the missing gland 19. Since the parathyroid glands have an end organ blood supply, it can be eliminated by tying off the ipsilateral inferior thyroidal artery. Udelsman and colleagues reported their success with this technique which led to surgical cure in 3 patients undergoing re-operative parathyroidectomy 19.

Conclusion

Hyperparathyroidism is a disease that is seen often in the United States. Patients may present with a wide variety of symptoms affecting multiple organs, but frequently they are found to be hyperparathyroid on a routine blood examination. Although, these patients may be asymptomatic, new consensus guidelines exist for when they should undergo surgery and several studies have shown multiple benefits from operative intervention. Surgical cure rates can be over 95%, but in the event that the initial surgery is unsuccessful, the cure rate becomes 80%. In the hands of experienced surgeons, both initial cure rates and those for reoperations are much higher, illustrating that surgical volume does affect failure in parathyroid surgery.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Udelsman R. Six hundred fifty-six consecutive explorations for primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Surg. 2002 May;235(5):665–670. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00008. discussion 670-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, Pruhs Z, Starling J, Mack E. Intraoperative parathyroid hormone testing improves cure rates in patients undergoing minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. Surgery. 2005 Oct;138(4):583–587. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.046. discussion 587-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sosa J, Powe N, Levine M, Udelsman R, Zeiger M. Profile of a clinical practice: Thresholds for surgery and surgical outcomes for patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: a national survey of endocrine surgeons. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Aug;83(8):2658–2665. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.8.5006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson G, Grant C, Perrier N, et al. Reoperative parathyroid surgery in the era of sestamibi scanning and intraoperative parathyroid hormone monitoring. Arch Surg. 1999 Jul;134(7):699–704. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.7.699. discussion 704-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty GM. Parathyroid Glands. In: Mulholland MW, editor. Greenfield's Surgery: Scientific Principles and Practice. Fourth ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark O, Wilkes W, Siperstein A, Duh Q. Diagnosis and management of asymptomatic hyperparathyroidism: safety, efficacy, and deficiencies in our knowledge. J Bone Miner Res. 1991 Oct;6(Suppl 2):S135–142. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650061428. discussion 151-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon B, Schaaf M, Smallridge R. Psychologic symptoms before and after parathyroid surgery. Am J Med. 1994 Feb;96(2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler J, Sippel R, Schaefer S, Chen H. Surgery improves quality of life in patients with “mild” hyperparathyroidism. Am J Surg. 2009 Mar;197(3):284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverberg S, Gartenberg F, Jacobs T, et al. Increased bone mineral density after parathyroidectomy in primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995 Mar;80(3):729–734. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.3.7883824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilezikian J, Khan A, Potts JJ, Hyperthyroidism TIWotMoAP. Guidelines for the management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: summary statement from the third international workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Feb;94(2):335–339. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Zeiger M, Gordon T, Udelsman R. Parathyroidectomy in Maryland: effects of an endocrine center. Surgery. 1996 Dec;120(6):948–952. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80039-0. discussion 952-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowney J, Weber B, Johnson S, Doherty G. Minimal incision parathyroidectomy: cure, cosmesis, and cost. World J Surg. 2000 Nov;24(11):1442–1445. doi: 10.1007/s002680010238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health NIo. [October 1, 2010];Hyperparathyroidism. http://endocrine.niddk.nih.gov/pubs/hyper/hyper.htm.

- 14.Memmos D, Williams G, Eastwood J, et al. The role of parathyroidectomy in the management of hyperparathyroidism in patients on maintenance haemodialysis and after renal transplantation. Nephron. 1982;30(2):143–148. doi: 10.1159/000182451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triponez F, Clark O, Vanrenthergem Y, Evenepoel P. Surgical treatment of persistent hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation. Ann Surg. 2008 Jul;248(1):18–30. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181728a2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerby J, Rue L, Blair H, Hudson S, Sellers M, Diethelm A. Operative treatment of tertiary hyperparathyroidism: a single-center experience. Ann Surg. 1998 Jun;227(6):878–886. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199806000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilgo M, Pirsch J, Warner T, Starling J. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation: surgical strategy. Surgery. 1998 Oct;124(4):677–683. doi: 10.1067/msy.1998.91483. discussion 683-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell J, Milas M, Barbosa G, Sutton J, Berber E, Siperstein A. Avoidable reoperations for thyroid and parathyroid surgery: effect of hospital volume. Surgery. 2008 Dec;144(6):899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.022. discussion 906-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Udelsman R, Donovan P. Remedial parathyroid surgery: changing trends in 130 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2006 Sep;244(3):471–479. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234899.93328.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan E, O'Donnell J, Kilburn HJ, Bernard H, Yazici A. Investigation of the relationship between volume and mortality for surgical procedures performed in New York State hospitals. JAMA. 1989 Jul;262(4):503–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieberman M, Kilburn H, Lindsey M, Brennan M. Relation of perioperative deaths to hospital volume among patients undergoing pancreatic resection for malignancy. Ann Surg. 1995 Nov;222(5):638–645. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jollis J, Peterson E, DeLong E, et al. The relation between the volume of coronary angioplasty procedures at hospitals treating Medicare beneficiaries and short-term mortality. N Engl J Med. 1994 Dec;331(24):1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412153312406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stavrakis A, Ituarte P, Ko C, Yeh M. Surgeon volume as a predictor of outcomes in inpatient and outpatient endocrine surgery. Surgery. 2007 Dec;142(6):887–899. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.09.003. discussion 887-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H, Wang T, Yen T, et al. Operative failures after parathyroidectomy for hyperparathyroidism: the influence of surgical volume. Ann Surg. 2010 Oct;252(4):691–695. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f698df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seehofer D, Steinmüller T, Rayes N, et al. Parathyroid hormone venous sampling before reoperative surgery in renal hyperparathyroidism: comparison with noninvasive localization procedures and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2004 Dec;139(12):1331–1338. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.12.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hessman O, Stålberg P, Sundin A, et al. High success rate of parathyroid reoperation may be achieved with improved localization diagnosis. World J Surg. 2008 May;32(5):774–781. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9537-5. discussion 782-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conrad D, Olson J, Hartwig H, Mack E, Chen H. A prospective evaluation of novel methods to intraoperatively distinguish parathyroid tissue utilizing a parathyroid hormone assay. J Surg Res. 2006 Jun;133(1):38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yen T, Wang T, Doffek K, Krzywda E, Wilson S. Reoperative parathyroidectomy: an algorithm for imaging and monitoring of intraoperative parathyroid hormone levels that results in a successful focused approach. Surgery. 2008 Oct;144(4):611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.06.017. discussion 619-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell A, Alexander H, Chang R, et al. Reoperation for parathyroid adenoma: a contemporary experience. Surgery. 2009 Dec;146(6):1144–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prescott J, Udelsman R. Remedial operation for primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg. 2009 Nov;33(11):2324–2334. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9962-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold J, Donovan P, Udelsman R. Partial median sternotomy: an attractive approach to mediastinal parathyroid disease. World J Surg. 2006 Jul;30(7):1234–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7904-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chae A, Perricone A, Brumund K, Bouvet M. Outpatient video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for ectopic mediastinal parathyroid adenoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008 Jun;18(3):383–390. doi: 10.1089/lap.2007.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook M, Pitt S, Schaefer S, Sippel R, Chen H. A rising ioPTH level immediately after parathyroid resection: are additional hyperfunctioning glands always present? An application of the Wisconsin Criteria. Ann Surg. 2010 Jun;251(6):1127–1130. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3d264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cayo A, Sippel R, Schaefer S, Chen H. Utility of intraoperative PTH for primary hyperparathyroidism due to multigland disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 Dec;16(12):3450–3454. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irvin Gr, Molinari A, Figueroa C, Carneiro D. Improved success rate in reoperative parathyroidectomy with intraoperative PTH assay. Ann Surg. 1999 Jun;229(6):874–878. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00015. discussion 878-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H, Mack E, Starling J. A comprehensive evaluation of perioperative adjuncts during minimally invasive parathyroidectomy: which is most reliable? Ann Surg. 2005 Sep;242(3):375–380. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179622.37270.36. discussion 380-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy C, Norman J. The 20% rule: a simple, instantaneous radioactivity measurement defines cure and allows elimination of frozen sections and hormone assays during parathyroidectomy. Surgery. 1999 Dec;126(6):1023–1028. doi: 10.1067/msy.2099.101578. discussion 1028-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cayo A, Chen H. Radioguided reoperative parathyroidectomy for persistent primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Nucl Med. 2008 Oct;33(10):668–670. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318184b465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pitt S, Panneerselvan R, Sippel R, Chen H. Radioguided parathyroidectomy for hyperparathyroidism in the reoperative neck. Surgery. 2009 Oct;146(4):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.031. discussion 598-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Sippel R, Schaefer S. The effectiveness of radioguided parathyroidectomy in patients with negative technetium tc 99m-sestamibi scans. Arch Surg. 2009 Jul;144(7):643–648. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]