Abstract

Aims

Genetic research on substance use disorders usually defines phenotypes as a binary diagnosis, resulting in a loss of information if the disorder is inherently dimensional. The DSM-IV criteria for drug dependence were based on a theoretically dimensional (linear) model. Considerable investigation has been conducted on DSM-IV alcohol criteria, but less is known about the dimensionality of DSM-IV cannabis criteria for abuse and dependence. The aim of this study is to assess whether DSM-IV cannabis dependence (including withdrawal) and abuse criteria fit a linear measure of severity and whether a consumption criterion adds linearly to severity.

Design/Setting/Participants/Measurements

Participants were 8,172 in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions who had ever used cannabis. Wald statistics were used to test whether categorical, dimensional or hybrid forms best fit the data. We examined the following as criterion sets: (1) dependence; (2) dependence and abuse; and (3) dependence, abuse and frequency of use. Validating variables included family history of drug problems, early onset of cannabis use, and antisocial personality disorder.

Findings

For cannabis dependence, no evidence was found for categorical or hybrid models; Wald tests indicated that models representing the seven DSM-IV dependence criteria as a linear severity measure best described the association between the criteria and validating variables. However, significant differences from linearity occurred after adding the four cannabis abuse criteria (p=0.03) and the use indicator (p=0.01) for family history and antisocial personality disorder.

Conclusion

With ample power to detect non-linearity, cannabis dependence was shown to form an underlying continuum of severity. However, adding abuse criteria, with and without a measure of consumption, resulted in a model that differed significantly from linearity for two of the three validating variables.

Keywords: cannabis, substance use disorders, diagnostic criteria, dimensionality, DSM-IV

1. Introduction

1.1

Cannabis is the most widely used illegal drug in many countries (Copeland & Swift 2009; Stinson, Ruan, Pickering & Grant, 2006; Hall, Teesson, Lynskey & Degenhardt, 1999). Cannabis use may result in withdrawal (Budney, Hughes, Moore & Vandrey, 2004; Haney et al., 2004; Hasin, Keyes, Alderson, Wang, Aharonovich & Grant, 2008) and diagnoses of abuse and dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Since 1994, DSM-IV has provided diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders that have been used across mental health disciplines for many purposes. However, research developments and experience with DSM-IV have raised issues now under consideration regarding DSM-V. These include (1) whether diagnoses should have dimensional representations, (2) whether related disorders should be consolidated into a single category, and (3) whether adding new criteria improves a particular diagnosis.

1.1.1, Issue 1: Dimensional representation

The basis of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV substance dependence criteria (Rounsaville, Spitzer & Williams, 1986) was the Dependence Syndrome (Edwards & Gross, 1976; Edwards, Arif & Hadgson, 1981; Edwards, 1986), a construct assumed to be dimensional (i.e., occurring in gradations of severity) that represented impaired control over substance use. The neuroadaptive changes that produce impaired control were hypothesized to be similar across all substances (Koob, 1992; Nestler, Hope & Widnell, 1993; Hasin, Grant, Harford & Endicott, 1988). If the same neuronal systems mediate reinforcement of all addictive drugs, then a similar gradient of clinical manifestations should be seen across all substances. If a given substance disorder is inherently graded, then etiologic research using dichotomized measures (i.e. defining yes/no categories), as is presently the case in DSM-IV, imposes an artificial threshold, which may result in the loss of potentially important information and increased difficulty in identifying etiologic factors. The validity of a dimensional representation of substance use disorders (SUDs) is currently under study as a potential addition to DSM-V (Helzer, Bucholz & Gossop, 2007).

1.1.2. Issue 2: Combining highly related disorders

DSM-IV operationalized dependence and abuse (consequences) as two separate and hierarchical disorders, with dependence taking precedence over abuse if criteria for both are met. However, questions for DSM-V include the validity of the hierarchical division of SUDs into dependence and abuse, and whether the two disorders should be combined (Hasin, Hatzenbuehler, Keyes & Ogburn, 2006a; Schuckit & Saunders, 2006; Saha, Chou & Grant, 2006; Martin, Chung, Kirisci & Langenbucher, 2006).

1.1.3. Issue 3: Adding new criteria

A set of diagnostic criteria lacking important elements will be less sensitive or specific than a set incorporating all relevant elements. However, reasons for not adding criteria include (1) keeping criteria sets simpler for clinical use (Hasin et al., 2003), and (2) expanded heterogeneity. Thus, when new criteria are proposed, their effect on the psychometric performance of the entire criteria set requires scrutiny to justify their addition. For current alcohol use disorders, such a proposed criterion is current binge drinking, defined as 5+ drinks per occasion at least weekly for men, and 4+ drinks for women (Saha, Stinson & Grant, 2007; Li, Hewitt & Grant, 2007; Keyes, Geier, Grant & Hasin, 2009). A parallel criterion proposed for cannabis is based on weekly use (Compton, Saha, Conway & Grant, 2009). A second criterion for possible addition to DSM-V is cannabis withdrawal.

1.2. Approaches to investigating abuse and dependence criteria

Latent variable analyses including latent class analyses (LCA), factor analyses and item response theory analyses (IRT) have been used to address the psychometric properties of cannabis abuse and dependence (Helzer et al., 2007). In both population-based (Grant et al., 2006) and treated adolescents, (Chung & Martin, 2005), LCA identified classes of cannabis users based largely on severity. Investigators using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (Agrawal & Lynskey, 2007), male Virginia twins (Gillespie, Neale, Prescott, Aggen & Kendler, 2007) and the Australian general population (Teesson, Lynskey, Manor & Baillie, 2002) showed that 1- and 2-factor models corresponding to cannabis dependence and abuse fit the data well. However, they chose the 1-factor model due to high factor correlations in the 2-factor model, with two studies (Teesson et al., 2002; Agrawal & Lynskey, 2007) dropping some abuse items to achieve unidimensionality. Using NLAES data (Blanco, Harford, Nunes, Grant & Hasin, 2007), two factors were also found for cannabis abuse and dependence criteria, with a correlation of .77 between the two factors. A criterion for weekly cannabis use fit a one-factor model of current cannabis abuse and dependence criteria in current users in NESARC and showed low severity in an IRT analysis (Compton et al., 2009). Large sample sizes are better at showing smaller effect sizes to be statistically significant, which may favor models showing a greater number of factors (Agrawal & Lynskey, 2007); but this does not explain the significantly better fit of two-factor models in small studies such as Teesson et al., 2002.

1.3. Gaps in knowledge

While many investigators have preferred the unidimensional concept of abuse and dependence, the repeated appearance of two factors warrants additional attention. Further, none of the latent variable studies directly test whether a dimensional or binary model fit the data better, whether dimensionality is found only after the DSM-IV diagnostic threshold has been exceeded, or whether the criteria are dimensional in relation to known risk factors for SUDs. We therefore extended a statistical method used previously (Kendler & Gardner, 1998; Kendell & Brockington, 1980; Hasin, Liu, Alderson & Grant, 2006b; Hasin & Beseler, 2009), the “discontinuity approach” (Hasin & Beseler, 2009) to examine these issues.

1.4. The discontinuity approach

The discontinuity approach directly incorporates the relationship of an observed criterion set to important external validating variables. Assuming an inherent threshold exists in the diagnostic set, two underlying assumptions hold. (1) After a diagnostic threshold has been met, cases will show a stronger association between the number of criteria and a risk factor than non-cases. (2) The statistical association between the number of criteria and risk factors will be homogeneous within groups of cases and non-cases, i.e., among those designated a ‘non-case’, there will be no association between risk factors and number of criteria met. A theoretical depiction of these assumptions has been published previously (Hasin & Beseler, 2009). If the criteria are inherently dimensional and no threshold exists, then each additional criterion adds in equal measure to the severity of the disease resulting in a monotonically increasing linear relationship to a validating variable.

With the discontinuity approach focused on alcohol use disorders, we previously examined whether a dimensional representation of a disorder is warranted, whether abuse and dependence should be combined, and whether a new alcohol use criterion should be added to DSM-IV alcohol use disorder criteria. We found that the dependence criteria related to risk factors in a monotonic fashion, with no support for any model of alcohol dependence that included a category (Hasin et al., 2006b; Hasin & Beseler, 2009). Results did not support the addition of a binge drinking criterion (Hasin & Beseler, 2009). We now extend this approach to study lifetime criteria for cannabis dependence, abuse and use among the lifetime cannabis users from a national representative general population sample. We hypothesized that (1) the alcohol dependence syndrome applies to cannabis; (2) cannabis dependence and abuse criteria, like alcohol criteria, will show a linear relationship with the validating variables; (3) cannabis use will not fit on a linear continuum with other DSM-IV criteria.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

Respondents were participants in the NESARC. The full survey included 43,093 respondents, with over-sampling of African-Americans, Hispanics, and young adults (Grant et al., 2004). The NESARC face-to-face survey conducted by NIAAA in 2001-2002 targeted the adult civilian non-institutionalized population residing in the US, the District of Columbia, Alaska and Hawaii. The overall response rate was 81%. The sample analyzed consisted of the 8,172 NESARC participants who ever used cannabis during their lifetime. These respondents were 65.4% white, 15.9% black and 14.4% Hispanic, and 54.0% were male. By age, 26.7% were 18-29, 43.4% 30-44, 28.4% 45-64 and 1.5% were 65 or older.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. DSM-IV Diagnostic Interview

The structured interview used in NESARC was the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) designed for lay interviewers (Grant et al., 2004). Professional interviewers administered the AUDADIS-IV using laptop computer-assisted software with built-in skip logic and consistency checks (Grant et al., 2004). Training and quality control procedures are described elsewhere (Grant et al., 2004; Grant et al., 2005; Hasin, Stinson, Ogburn & Grant, 2007). The diagnostic measures for the substance use disorders and their reliability and validity have been described extensively (Grant et al., 2003; Grant et al., 2004; Hasin et al., 2007; Compton, Thomas, Stinson & Grant, 2007). Lifetime use of cannabis and age at first use as measured in AUDADIS have good to excellent reliability (Grant, Harford, Dawson, Chou & Pickering, 1995; Hasin, Carpenter, McCloud, Smith & Grant, 1997).

2.2.2. Cannabis abuse dependence and use

Six DSM-IV criteria for cannabis dependence and four criteria for abuse are measured in the AUDADIS among individuals that ever used cannabis (Grant et al., 1995). The six criteria of cannabis dependence include (1) tolerance; (2) persistent desire or unsuccessful attempts to reduce use; (3) time spent using cannabis or recovering from its effects; (4) giving up or reducing occupational, social and/or recreational activities to use; (5) impaired control; and (6) continued cannabis use despite physical or psychological problems. The four criteria for cannabis abuse included (1) failure to fulfill major role obligations; (2) recurrent physically hazardous use; (3) recurrent substance-related legal problems; and (4) continued substance use despite having persistent social or interpersonal problems related to use. Although cannabis withdrawal was not included in DSM-IV, numerous studies support its addition in DSM-V (Budney et al., 2004; Haney, 2005; Agrawal & Lynskey, 2007; Hasin et al., 2008), therefore, we added a withdrawal criterion to make a set of seven cannabis dependence criteria, analogous to the other substances in DSM-IV. We created the withdrawal variable by requiring two or more out of the following, after reduction or cessation in use: anxiety, insomnia, vivid or unpleasant dreams, hallucinations, restlessness, shaking, depressed mood, hypersomnia, psychomotor retardation, feeling weak or tired, bad headaches, muscle cramps, runny eyes or nose, yawning, nausea, sweating, fever, and seizure, and by requiring that the withdrawal symptoms caused significant distress. The definition of withdrawal was based on a previous report where withdrawal using a cutoff of two criteria, when added to the six DSM-IV dependence criteria, increased the prevalence of cannabis dependence from 16% to 32.3%; a cutoff of three withdrawal criteria resulted in a 30.1% prevalence (Hasin, Keyes, Alderson, Wang, Aharonovich & Grant, 2008). Further, the two latent factors representing withdrawal were each significantly associated with distress over symptoms. We tested whether requiring two or three criteria resulted in changes in linearity with the six dependence criteria and no significant differences were noted. For these reasons we used a cut-off of two withdrawal criteria and presence of distress due to experiencing the symptoms.

Cannabis consumption was ascertained from a question asking how often cannabis was used when using the most. Responses were as follows: (1) every day; (2) nearly every day; (3) 3-4 times per week; (4) 1-2 times per week; (5) 2-3 times per month; (6) once a month; (7) 7-11 times per year; (8) 3-6 times per year; (9) 2 times per year; and (10) once a year. Respondents who endorsed using 1-2 times per week or more often were coded as weekly users and zero if less often. This variable was dichotomized (at least weekly vs. less frequently) at the point that corresponded most closely to the binge drinking variable studied previously (Saha et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007; Hasin & Beseler, 2009; Compton et al., 2009).

2.2.3. Validating variables

The dimensionality of cannabis criteria was tested using three validating variables: family history of drug problems (Milne et al., 2009; Heiman, Ogburn, Gorroochurn, Keyes & Hasin, 2008; Bierut et al., 1998), age of onset of cannabis use (Copeland & Swift, 2009; Swift, Coffey, Carlin, Degenhardt & Patton, 2008) and DSM-IV antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) (Mariani et al., 2008; Compton, Conway, Stinson, Colliver & Grant, 2005; Fu et al., 2002). We considered treatment as a validating variable because we previously showed a strong linear relationship between the alcohol criteria and seeking treatment for an alcohol use disorder. However, because only 8% of the cannabis users were ever in treatment for their cannabis use, numbers were too small to use treatment as a validating variable. Family history was defined as the proportion of first-degree relatives with a drug problem relative to the total number of first-degree relatives that attained the initial age of risk for first drug use (> 10 years of age). Age of onset of cannabis use was dichotomized at 15 years (<15=1) from the question asking about age first used cannabis (possible responses, 5-64 years). Fifteen was chosen because analyses in the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse showed an increased risk of cannabis dependence in those who initiated use at 11-15 years of age (Chen, O’Brien & Anthony, 2005) and to be consistent with the previous alcohol dimensionality study (Hasin & Beseler, 2009). Sensitivity analyses dichotomizing at 14 and 16 did not alter the linear relationship between the dependence criteria and early age of onset. ASPD was diagnosed if respondents met full criteria for child conduct disorder as well as the adult symptoms required by DSM-IV. Control variables included sex (Guxens, Nebot & Ariza, 2007), age (a continuous variable) and race (whites compared to all others; Stinson et al., 2006).

2.2.4. Statistical analysis

Variables created for analysis

Dimensional Variables

Unidimensionality means that a sloping straight line describes the relationship between the number of DSM-IV criteria met (the X axis on a graph), and the risk for the validating variables (the Y axis on a graph). In our case, we hypothesized that such a line would be found, with its lowest point in the lower left quadrant of the graph, and its highest point at the upper right quadrant of a graph. In this case, each criterion endorsed would add linearly and equally to the shape of the line. We created a dimensional or linear representation (a sum score) by adding up the number of criteria endorsed by each participant. We used the sum score variable in separate regression models (referred to below as MNDimensional where N=7 dependence criteria, 11 dependence and abuse criteria and 12 dependence, abuse and use criteria depending on the model).

Dummy Variables

We next created a set of dummy variables, each representing one subset of the sample defined by the number of criteria they experienced. Dummy variables were used to avoid advance assumptions about the shape of the relationship between the number of criteria and the risk for the validators, instead allowing the actual relationships to form the shape of the line in regression models (which might have been linear, U-shaped, J-shaped, or without shape at all). For example, a person experiencing one criterion would be coded as positive (=1) for the dummy variable representing having endorsed one criterion and negative (=0) for all the rest of the dummy variables. A person who endorsed two criteria would be coded as positive=1 for the variable representing experiencing two criteria and negative=0 for all the rest of the dummy variables. Using this procedure, in analyses of dependence criteria, each individual contributed to only one of the seven variables representing one to seven dependence criteria, with similar procedures followed for the 11dependence and abuse criteria, and the twelve criteria for dependence, abuse and use. The seven (M7Dum), eleven (M11Dum) and twelve (M12Dum) dummy variables representing the various levels of severity were used in regression models.

To test a model in which those below the diagnostic threshold were homogeneous, but those above the threshold represented gradients of severity according to the number of dependence criteria met, we combined the dummy variables for 0 to 2 criteria into a single group representing being below the diagnostic threshold of 3 criteria. The dummy variables representing 3 to 7 criteria were not combined. We used this to create an artificial threshold at three criteria while allowing for a slope at or above three or more criteria (M7Threshtrend). We also created a DSM-IV model by allowing for no slope if fewer than 3 criteria were endorsed, a threshold at three criteria and no slope for three or greater criteria (MDSM-IV). In this way we could impose artificial thresholds and test whether they differed significantly from the model with seven dummy variables (Hasin et al., 2006b; Hasin & Beseler, 2009).

Regression models

Analyses were conducted with three sets of lifetime criteria: (1) cannabis dependence (range, 0-7); (2) cannabis dependence and abuse (range, 0-11); and (3) cannabis dependence, abuse and weekly use (range, 0-12). To determine the association between the criteria set and family history, Poisson regression models were used, with the outcome log ((EY)/N), where Y is the count of affected relatives and N is the total number of relatives in each family. Early onset of drinking and ASPD were modeled using logistic regression. Survey Data Analysis software (SUDAAN, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) was used to apply these models because it calculates correct estimates of the standard errors (via Taylor linearization) in complex survey designs such as the NESARC. We tested whether withdrawal fit a linear model in relation to the validating variables when added to the six dependence criteria. We also tested for a threshold at 3, 4 or 5 criteria after combining abuse and dependence criteria. All models were adjusted for age, gender and race.

Dimensionality of lifetime cannabis dependence criteria

Following the method we used previously (Hasin et al., 2006b; Hasin & Beseler, 2009), we began with a dummy variable model (M7Dum) with ten predictors: three control variables (age, gender and race) and seven non-ordered dummy variables to represent the seven levels of severity (1–7) of the cannabis dependence criteria. Participants with no cannabis dependence criteria constituted the reference group. Participants with one dependence criterion were compared to the reference group, as were participants with two dependence criteria, etc., up to participants with seven dependence criteria. Consistently increasing regression coefficients for dummy variables, as indicated by the slope of the regression line, would suggest an underlying dimensional relationship between the criteria and the validating variable. The regression line produced from the dimensional model (M7Dimensional) was compared to the line produced by dummy variable model (M7Dum) to determine whether they differed significantly. In addition to testing a purely linear model (M7Dimensional), we compared the M7Threshtrend to M7Dum to determine whether those endorsing 0-2 criteria were homogeneous (slope=0) but those with three or greater criteria showed an increasing level of dependence (slope> 0). Lastly, we tested whether the DSM-IV categorical model (MDSM-IV) fit the dummy variable model, i.e., those endorsing 0-2 criteria were homogeneous (slope=0) and those endorsing three or greater criteria were homogeneous (slope=0), but with the second category showing a greater level of cannabis dependence (a threshold effect).

To compare the models incorporating the weights reflecting the complex sample design, the Wald test was used to test the hypothesis that the slope parameters for the two models were identical. Each model was compared with the dummy variable model in the Wald test. While differences in the fit of nested models are often compared using the likelihood ratio test, this test cannot be used with weighted data. We used the Wald statistic to determine whether alternative parameterizations of the association between the validating variable and the number of dependence criteria produce significantly different estimates between M7Dum and M7Dimensional, with a single linear predictor (i.e., (β1, β2, …, β7) compared with (1β, 2β,…, 7β). The Wald test statistic is calculated using the squared distance between two vectors of estimated effects in the two nested models. Similar to the likelihood ratio test, it follows a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom defined as the difference in the number of parameters in the two nested models. With large samples such as the NESARC, the likelihood ratio test and Wald test are generally equivalent in testing the hypotheses on model parameters for the pattern in the association between outcome and predictors if no sampling weights applied (Pawitan, 2001). Little or no difference between the dummy variable model and the linear model would support the use of M7Dimensional, as it is most parsimonious. Following our previous methods, we considered that the dimensional model ‘fit’ the pattern in the dummy variable model better if the difference between the dummy and dimensional models were small (non-significant), while the difference between, for example, the dummy and DSM-IV model were not small (e.g. significantly different). For all tests, statistical significance was set at 0.05.

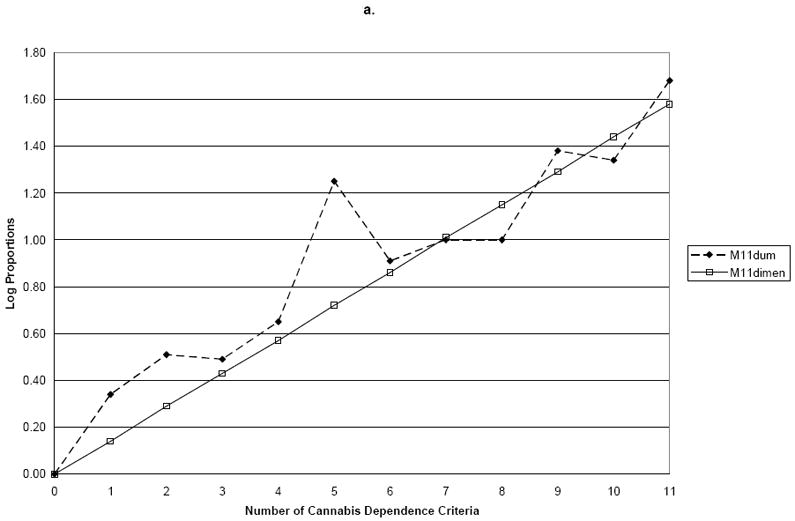

Dimensionality of lifetime cannabis dependence and abuse criteria

We analyzed only the dummy variable model with 7 dependence and 4 abuse criteria (M11Dum) and the criteria count variable model (M11Dimensional) using the same validating variables because no threshold is defined for the combined criteria. M11Dum, representing levels of severity (range 0-11), was compared with M11Dimensional, which used a continuous dimensional measure of criteria (range 0-11).

Dimensionality of lifetime cannabis dependence, abuse and use criteria

The variables were generated as described above, using a dummy variable model with 7 dependence, 4 abuse, and a criterion for weekly use. M12Dum contained 12 dummy variables and M12Dimensional contained a single indicator of criteria counts (range 0-12). M12Dum was compared to M12Dimensional.

Testing the dummy variable model

Prior to conducting these analyses, we used the Wald statistic to test whether the set of dummy variables in M7Dum, M11Dum and M12Dum were associated with each of the validating variables. For example, the null hypothesis on the parameters of M7Dum was (β1, β2, …, β7)=(0, 0, …, 0) for no association between the dependence criteria count and the validating variable, adjusting for age, gender and race. The null hypotheses were rejected (all p-values <0.0001).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

Table 1 shows the prevalence of dependence, abuse and weekly use criteria among this sample of lifetime cannabis users. Weekly use showed the highest prevalence, at 45.7% and withdrawal had the lowest prevalence (3.2%). Approximately 73% of the sample endorsed two or fewer criteria and less than 1% endorsed 10 or more criteria.

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence of cannabis abuse and dependence criteria and weekly use in NESARC lifetime cannabis users (N=8,134)

| Cannabis criterion | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Abuse | |

| Neglect roles | 8.4 |

| Hazardous use | 33.7 |

| Legal problems | 5.9 |

| Social/interpersonal problems | 16.0 |

| Dependence | |

| Tolerance | 10.0 |

| Withdrawal * | 3.2 |

| Larger/longer | 7.9 |

| Quit/control | 33.3 |

| Time spent | 11.5 |

| Activities given up | 5.5 |

| Physical/psychological problems | 10.6 |

| Consumption | |

| Weekly use | 45.7 |

Based on requiring two or more, after reduction or cessation in use: anxiety, insomnia, vivid or unpleasant dreams, hallucinations, restlessness, shaking, depressed mood, hypersomnia, psychomotor retardation, feeling weak or tired, bad headaches, muscle cramps, runny eyes or nose, yawning, nausea, sweating, fever, and seizure, and by requiring that the withdrawal symptoms caused significant distress.

3.2. Dimensionality of lifetime cannabis dependence criteria

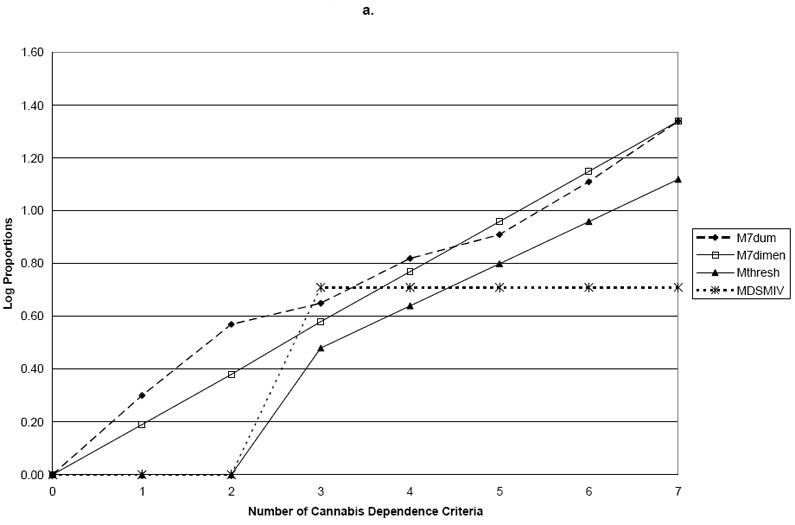

Using family history of drug problems as the validator, the log proportions for family history plotted against the seven dummy variables representing criterion counts (M7Dum) shows a monotonic, increasing linear relationship between the number of criteria and family history of drug use (Figure 1). Slope coefficients and their standard errors for the four dependence models are shown in Table 2. Comparing these points to the plotted line representing the continuous dimensional model (M7Dimensional) with a slope coefficient of 0.19 (s.e.=0.02) showed no significant difference between the two parameterizations of the criteria with family history (Wald=3.97; p=0.68). However, MThreshtrend and MDSM-IV significantly differed from M7Dum (p<0.0001). Using early age at onset as the validator, the plot of the log odds ratios for the dummy variable model shows points lying very close to the line representing the dimensional model (Figure 2). In this model, the M7Dimensional model had a slope coefficient of 0.20 (s.e.=0.02). No statistically significant differences were observed between M7Dum and M7Dimensional (Wald=9.84; p=0.13). However, MThreshtrend and MDSM-IV significantly differed from M7Dum (p<0.0001). Using ASPD as a validator, the plot shows that the points do not deviate greatly from the line representing the dimensional model (Figure 2). The slope coefficient for M7Dimensional was 0.37; s.e.=0.02. No statistically significant differences were observed between M7Dum and M7Dimensional (Wald=2.80; p=0.83) but MThreshtrend and MDSM-IV significantly differed from M7Dum (p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

a. Family History

b. Age of Onset

c. Antisocial Personality Disorder

Table 2.

Comparison of five models* representing cannabis dependence criteria in different forms: NESARC (N=8,172)

| Outcome | Criterion Count (K) | M7DumEstimate | M7dimensionaEstimatea | Mthreshtrend Estimatea | MDSM-IV Estimatea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log P(K)/P(0)b | |||||

| Family History | 1 | 0.30 (0.08) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 2 | 0.57 (0.13) | 0.38 (0.04) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | |

| 3 | 0.65 (0.14) | 0.58 (0.05) | 0.48 (0.31) | 0.71 (0.09) | |

| 4 | 0.82 (0.18) | 0.77 (0.07) | 0.64 (0.34) | 0.71 (0.09) | |

| 5 | 0.91 (0.18) | 0.96 (0.09) | 0.80 (0.38) | 0.71 (0.09) | |

| 6 | 1.11 (0.20) | 1.15 (0.11) | 0.96 (0.42) | 0.71 (0.09) | |

| 7 | 1.34 (0.21) | 1.34 (0.13) | 1.12 (0.47) | 0.71 (0.09) | |

| P-value for test of difference with M7Dum | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Log (Odds(K)/Odds(0))b | |||||

| Age of Onset | 1 | 0.04 (0.10) | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 2 | 0.64 (0.14) | 0.41 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | |

| 3 | 0.61 (0.16) | 0.61 (0.07) | 0.48 (0.39) | 0.72 (0.10) | |

| 4 | 0.70 (0.20) | 0.82 (0.10) | 0.66 (0.43) | 0.72 (0.10) | |

| 5 | 0.96 (0.23) | 1.02 (0.12) | 0.85 (0.49) | 0.72 (0.10) | |

| 6 | 1.23 (0.25) | 1.22 (0.14) | 1.03 (0.54) | 0.72 (0.10) | |

| 7 | 1.25 (0.39) | 1.43 (0.17) | 1.21 (0.60) | 0.72 (0.10) | |

| P-value for test of difference with M7Dum | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Log (Odds(K)/Odds(0))b | |||||

| Antisocial Personality | |||||

| 1 | 0.42 (0.12) | 0.37 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | |

| 2 | 0.88 (0.15) | 0.73 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | |

| 3 | 1.34 (0.22) | 1.10 (0.07) | 1.09 (0.48) | 1.43 (0.11) | |

| 4 | 1.58 (0.21) | 1.47 (0.09) | 1.34 (0.53) | 1.43 (0.11) | |

| 5 | 1.81 (0.21) | 1.83 (0.11) | 1.59 (0.58) | 1.43 (0.11) | |

| 6 | 2.08 (0.23) | 2.20 (0.14) | 1.85 (0.64) | 1.43 (0.11) | |

| 7 | 2.36 (0.33) | 2.57 (0.16) | 2.10 (0.71) | 1.43 (0.11) | |

| P-value for test of difference with M7Dum | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

K represents number of criteria present compared to the reference group with 0 criteria

Adjusted for age (continuous), gender (0=female, 1=male) and race (white=1, others=0).

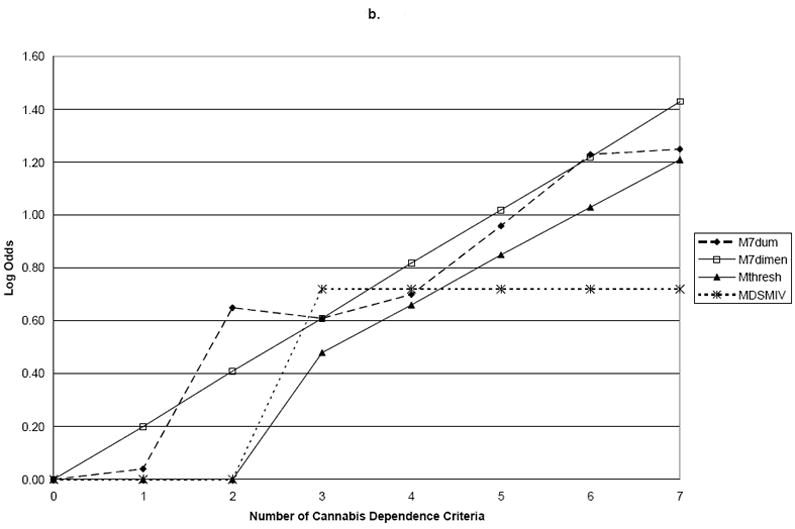

Figure 2.

a. Family History

b. Age of Onset

c. Antisocial Personality Disorder

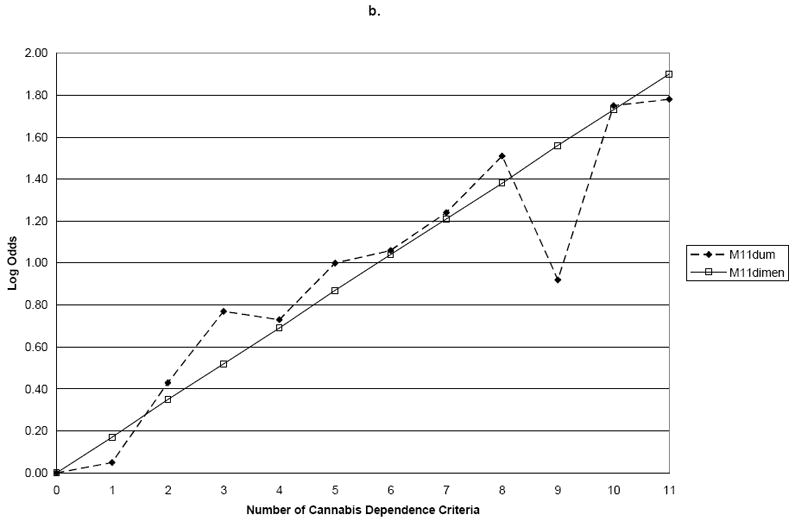

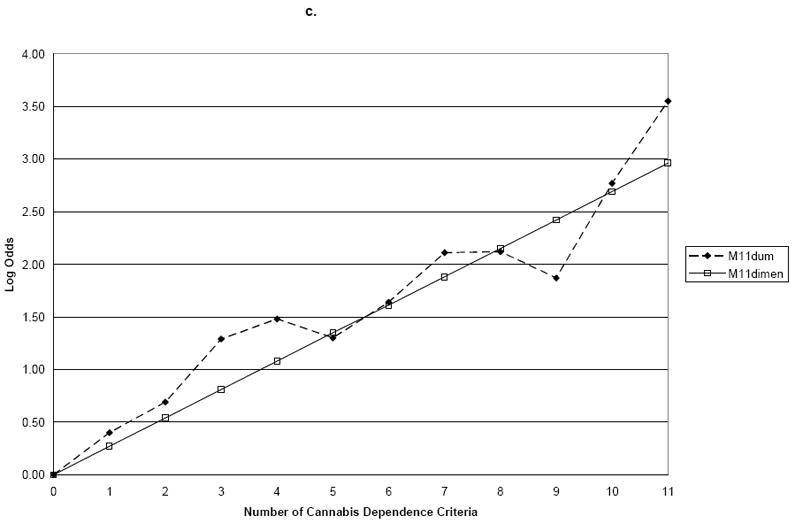

3.3. Dimensionality of lifetime cannabis dependence and abuse criteria

We next examined the combination of cannabis dependence and abuse criteria. The slope coefficient for M11Dimensional was 0.14 (s.e.=0.01) for family history, 0.17 (s.e.=0.02) for age of onset, and 0.27 (s.e.=0.02) for ASPD (Table 3). In contrast to the results for cannabis using only the dependence criteria, the addition of four cannabis abuse criteria resulted in significant deviations from linearity in relation to the validating variables family history (Wald=20.1, p=0.03) and ASPD (Wald=20.0, p=0.03), but not early age of onset (Wald=15.2, p=0.12) (Table 3 and Figure 2). Thus, when the cannabis abuse criteria were added to the dependence criteria, a single continuum of severity was no longer found for two of the three validating variables. Further, there was no evidence for a threshold at endorsement of 3, 4 or 5 cannabis dependence and abuse criteria (results not shown).

Table 3.

Comparison of the dummy variable model M11Dum to the dimensional model M11dimensional, representing 11 cannabis dependence and abuse criteria in NESARC participants (N=8,172)*

| Outcome | Criterion Count (K) | M11Dum Estimate | M11dimensional Estimate* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log P(K)/P(0)a | |||

| Family History | 1 | 0.34 (0.09) | 0.14 (0.01) |

| 2 | 0.51 (0.11) | 0.29 (0.02) | |

| 3 | 0.49 (0.15) | 0.43 (0.03) | |

| 4 | 0.65 (0.15) | 0.57 (0.05) | |

| 5 | 1.25 (0.15) | 0.72 (0.06) | |

| 6 | 0.91 (0.19) | 0.86 (0.07) | |

| 7 | 1.00 (0.27) | 1.01 (0.08) | |

| 8 | 1.00 (0.20) | 1.15 (0.09) | |

| 9 | 1.38 (0.21) | 1.29 (0.10) | |

| 10 | 1.34 (0.31) | 1.44 (0.11) | |

| 11 | 1.68 (0.31) | 1.58 (0.12) | |

| Pvalue for test of difference with M11Dum | 0.03 | ||

| Log (Odds(K)/Odds(0))a | |||

| Age of Onset | 1 | 0.05 (0.12) | 0.17 (0.02) |

| 2 | 0.43 (0.14) | 0.35 (0.03) | |

| 3 | 0.77 (0.15) | 0.52 (0.05) | |

| 4 | 0.73 (0.17) | 0.69 (0.06) | |

| 5 | 1.00 (0.19) | 0.87 (0.08) | |

| 6 | 1.06 (0.24) | 1.04 (0.09) | |

| 7 | 1.24 (0.27) | 1.21 (0.11) | |

| 8 | 1.51 (0.27) | 1.38 (0.12) | |

| 9 | 0.92 (0.30) | 1.56 (0.14) | |

| 10 | 1.75 (0.37) | 1.73 (0.15) | |

| 11 | 1.78 (0.51) | 1.90 (0.17) | |

| Pvalue for test of difference with M11Dum | 0.12 | ||

| Log (Odds(K)/Odds(0))a | |||

| Antisocial Personality | 1 | 0.40 (0.14) | 0.27 (0.02) |

| 2 | 0.69 (0.16) | 0.54 (0.03) | |

| 3 | 1.29 (0.19) | 0.81 (0.05) | |

| 4 | 1.48 (0.20) | 1.08 (0.06) | |

| 5 | 1.30 (0.23) | 1.35 (0.08) | |

| 6 | 1.64 (0.25) | 1.61 (0.09) | |

| 7 | 2.11 (0.25) | 1.88 (0.11) | |

| 8 | 2.12 (0.25) | 2.15 (0.12) | |

| 9 | 1.87 (0.28) | 2.42 (0.14) | |

| 10 | 2.77 (0.32) | 2.69 (0.15) | |

| 11 | 3.55 (0.52) | 2.96 (0.17) | |

| Pvalue for test of difference with M11Dum | 0.03 | ||

K represents number of criteria present compared to the reference group with 0 criteria

Adjusted for age (continuous), gender (0=female, 1=male) and race (white=1, others=0).

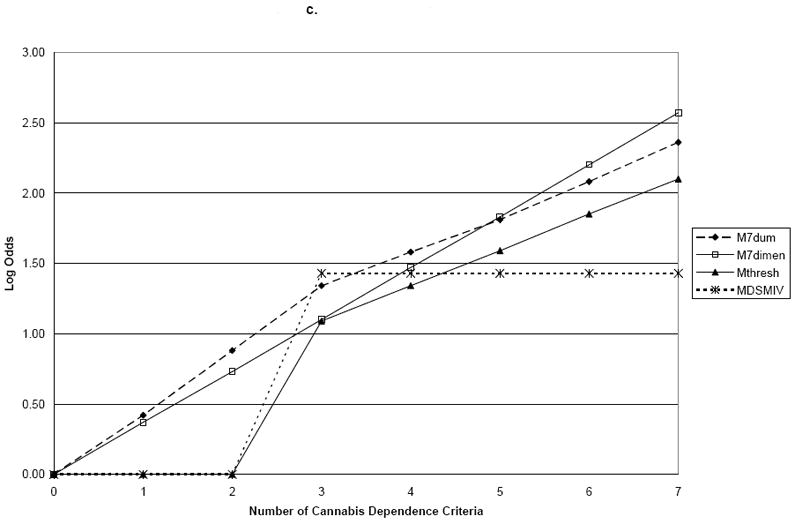

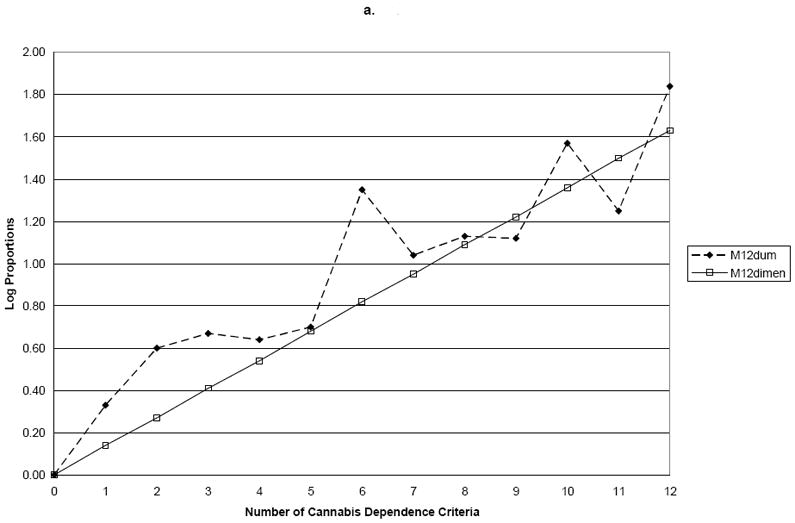

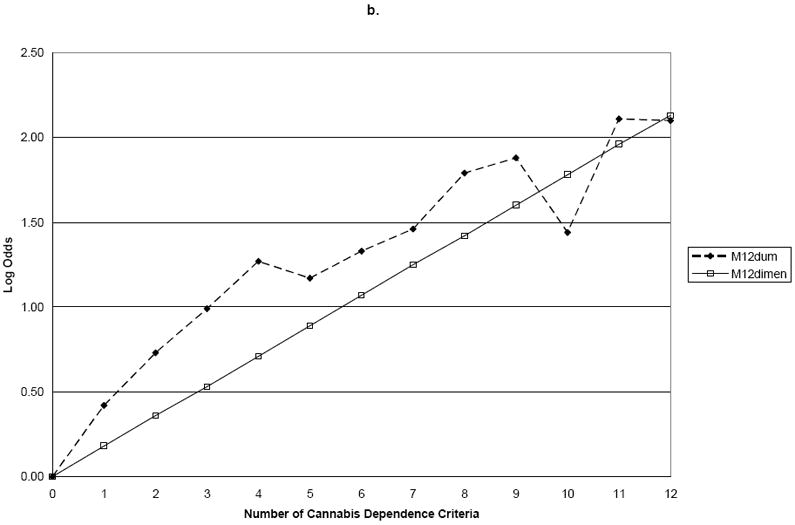

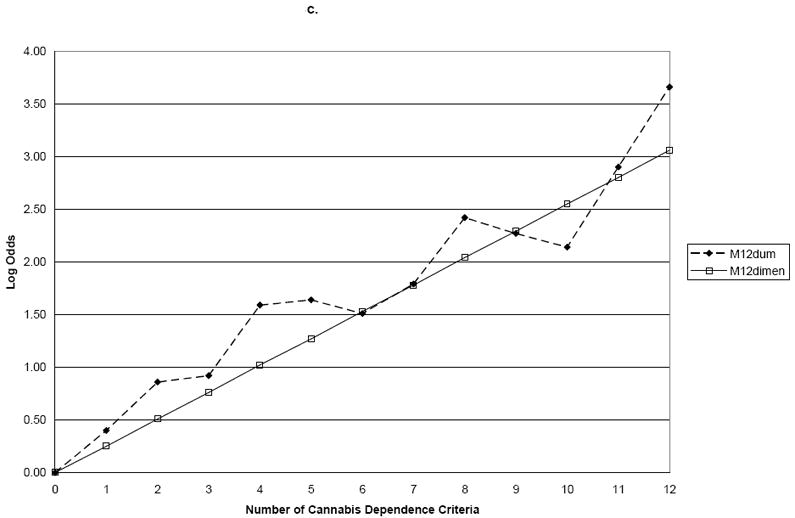

3.4. Dimensionality of lifetime cannabis dependence, abuse and use criteria

Finally, we examined the combination of cannabis dependence and abuse criteria with the addition of cannabis use. The slope coefficient for M12Dimensional was 0.14 (s.e. 0.01) for family history, 0.18 (s.e. 0.01) for age of onset, and 0.25 (s.e. 0.01) for ASPD (Table 4 and Figure 3). M12Dum and M12Dimensional differed significantly for family history (Wald=26.7, p=0.01) and ASPD (Wald=24.5, p=0.01), but not for early age of onset (Wald=19.2, p=0.06) (Table 5 and Figure 4). Thus, when cannabis abuse criteria and a consumption measure were added to the dependence criteria, a single continuum of severity was not found for family history or ASPD.

Table 4.

Comparison of the dummy variable model M12Dum to the dimensional model M12dimensional representing 12 cannabis dependence, abuse and weekly consumption criteria in NESARC participants (N=8,172)*

| Outcome | Criterion Count (K) | M12Dum Estimate | M12dimensional Estimate* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log P(K)/P(0)a | |||

| Family History | 1 | 0.33 (0.09) | 0.14 (0.01) |

| 2 | 0.60 (0.11) | 0.27 (0.02) | |

| 3 | 0.67 (0.12) | 0.41 (0.03) | |

| 4 | 0.64 (0.15) | 0.54 (0.04) | |

| 5 | 0.70 (0.17) | 0.68 (0.05) | |

| 6 | 1.35 (0.15) | 0.82 (0.06) | |

| 7 | 1.04 (0.18) | 0.95 (0.07) | |

| 8 | 1.13 (0.31) | 1.09 (0.08) | |

| 9 | 1.12 (0.20) | 1.22 (0.09) | |

| 10 | 1.57 (0.20) | 1.36 (0.10) | |

| 11 | 1.25 (0.34) | 1.50 (0.11) | |

| 12 | 1.84 (0.31) | 1.63 (0.12) | |

| Pvalue for test of difference with M12Dum | 0.01 | ||

| Log (Odds(K)/Odds(0))a | |||

| Age of Onset | 1 | 0.42 (0.15) | 0.18 (0.01) |

| 2 | 0.73 (0.15) | 0.36 (0.03) | |

| 3 | 0.99 (0.16) | 0.53 (0.04) | |

| 4 | 1.27 (0.18) | 0.71 (0.06) | |

| 5 | 1.17 (0.20) | 0.89 (0.07) | |

| 6 | 1.33 (0.22) | 1.07 (0.08) | |

| 7 | 1.46 (0.24) | 1.25 (0.10) | |

| 8 | 1.79 (0.27) | 1.42 (0.11) | |

| 9 | 1.88 (0.31) | 1.60 (0.13) | |

| 10 | 1.44 (0.30) | 1.78 (0.14) | |

| 11 | 2.11 (0.39) | 1.96 (0.15) | |

| 12 | 2.10 (0.54) | 2.13 (0.17) | |

| Pvalue for test of difference with M12Dum | 0.06 | ||

| Log (Odds(K)/Odds(0))a | |||

| Antisocial Personality | 1 | 0.40 (0.15) | 0.25 (0.01) |

| 2 | 0.86 (0.16) | 0.51 (0.03) | |

| 3 | 0.92 (0.18) | 0.76 (0.04) | |

| 4 | 1.59 (0.19) | 1.02 (0.06) | |

| 5 | 1.64 (0.21) | 1.27 (0.07) | |

| 6 | 1.51 (0.24) | 1.53 (0.08) | |

| 7 | 1.79 (0.24) | 1.78 (0.10) | |

| 8 | 2.42 (0.24) | 2.04 (0.11) | |

| 9 | 2.27 (0.26) | 2.29 (0.13) | |

| 10 | 2.14 (0.28) | 2.55 (0.14) | |

| 11 | 2.90 (0.34) | 2.80 (0.16) | |

| 12 | 3.66 (0.54) | 3.06 (0.17) | |

| Pvalue for test of difference with M12Dum | 0.01 | ||

K represents number of criteria present compared to the reference group with 0 criteria

Adjusted for age (continuous), gender (0=female, 1=male) and race (white=1, others=0).

Figure 3.

a. Family History

b. Age of Onset

c. Antisocial Personality Disorder

4. Discussion

Lifetime cannabis dependence criteria represented a continuum of severity in those who ever used cannabis in relation to family history of drug use, early age of onset and ASPD. No support was found for a model including categories either below the DSM-IV diagnostic threshold for cannabis dependence, at the present DSM-IV threshold, or at any of several thresholds. Therefore, results for cannabis dependence criteria supported the dimensional construct underlying the Dependence Syndrome (Edwards & Gross, 1976). Our results are consistent with previous analyses showing that cannabis dependence criteria share an underlying construct (Swift, Hall & Teesson, 2001; Nelson, Rehm, Ustun, Grant & Chatterjial, 1999; Feingold & Rounsaville, 1995; Denson & Earleywine, 2006). The findings on cannabis dependence criteria, including withdrawal, contribute to the existing literature showing that cannabis dependence is a unidimensional construct by relating this continuum to validating variables with well-established relationships to a cannabis use disorder. These results are in agreement with our previous studies on the unidimensionality of alcohol dependence using family history and age of onset as validating variables (Hasin et al., 2006b; Hasin & Beseler, 2009).

In contrast, when cannabis dependence and abuse criteria were combined, they no longer showed a linear relationship to family history or ASPD, although a linear relationship was still seen for age of onset of cannabis use. The non-linearity of family history to the combined criteria suggests that caution should be taken when combining cannabis dependence and abuse criteria to create a phenotypic quantitative variable in genetics studies, as doing so may introduce heterogeneity.

To explore heterogeneity in the family history models, which have direct implications for genetic research, we removed each abuse criterion one at a time. We ran the models with three abuse criteria; two abuse criteria; and, finally, only one abuse criterion to identify which criterion or criteria were creating the non-linearity in the relationship to the validating variables. The family history model became linear in relation to the cannabis criteria after excluding legal problems and hazardous use. Addition of a consumption variable resulted in greater deviations from linearity, representing increased heterogeneity.

Combining cannabis dependence and abuse criteria in DSM-V requires that the question of a diagnostic threshold be addressed. We tested for a discontinuity at endorsing 3, 4 and 5 dependence and abuse criteria and found no evidence for a threshold. The lack of evidence for a diagnostic threshold indicates that a decision regarding a threshold for DSM-V will require taking into account considerations other than empirical evidence for a natural threshold or division between cases and non-cases.

The discontinuity approach differs from CFA, LCA and IRT model analysis in important ways. These differences may account for some of the discrepant results between the present report and the IRT approach where cannabis use was found to fit a single factor and fall on a spectrum of severity in the current timeframe in NESARC (Compton et al., 2009). First, the discontinuity approach is based on the number of criteria endorsed and not on the properties of the individual items. Second, the approach directly incorporates validation of the criteria set through their relationship to key risk factors. Third, the approach allows for adjustment for important covariates such as gender and age, a feature not available in IRT analysis. Fourth, the method addresses observed rather than latent variables, which are the “variables” actually used in clinical practice. Further, the discontinuity approach has been described as advantageous since it avoids the assumptions required of LCA and IRT that are not always met in practice (Helzer et al., 2007). Thus, while latent variable approaches have contributed important information that has greatly informed discussions about the structure of substance diagnoses, the discontinuity approach offers the advantage of an additional methodology in evaluating alterations to existing sets of diagnostic criteria.

Study strengths and limitations are noted. First, dependence and abuse symptoms were measured via retrospective structured self-report rather than observation, as was family history, early drinking onset and ASPD However, all variables had good to excellent test-retest reliability and the measures of substance use disorders have been validated in many paradigms. Second, the study was cross-sectional. A prospective study is needed to confirm these relationships. Third, cannabis, as an illicit substance, may be associated with ASPD through disinhibitory personality traits and not directly related to cannabis use in some people. Fourth, it would have been of interest to conduct this research with additional substances, but the number of participants using other substances was too limited. Other strengths of the work include a focus on lifetime rather than current variables, a timeframe that is important for epidemiologic and genetic studies.

5. Conclusion

Our study evaluated the dimensionality of lifetime cannabis abuse and dependence criteria to provide information for DSM-V, to identify the set of criteria that best discriminates problem cannabis users and facilitates treatment decisions and for refining variables used in genetic and epidemiological studies. Using a method that connects the criteria to established severity indicators, we showed that combining abuse and dependence can introduce heterogeneity that may be unwanted for some genetic and epidemiological purposes. A useful quantitative phenotype should be correlated with diagnosis and also represent severity of a disease (Almasy, 2003). Using validating variables such as family history, age of onset, or ASPD gives meaningful context because these variables reflect susceptibility (Almasy, 2003). Finally, the results contribute information about the performance of cannabis abuse, dependence and consumption as criteria for cannabis use disorders in DSM-V based on a different approach from that provided by CFA, IRT and LCA. These findings are clinically useful for identifying the set of criteria that best discriminates problem cannabis users and facilitates treatment decisions. The results are timely as they contribute to a convergent picture for the DSM-V Substance Use Disorders Workgroup.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Does gender contribute to heterogeneity in criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence? Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasy L. Quantitative risk factors as indices of alcoholism susceptibility. Annals of Medicine. 2003;35:337–343. doi: 10.1080/07853890310004903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Dinwiddie SH, Begleiter H, Crowe RR, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger JI, Porjesz B, Schuckit MA, Reich T. Familial transmission of substance dependence: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and habitual smoking: a report from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:982–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Harford TC, Nunes E, Grant B, Hasin D. The latent structure of marijuana and cocaine use disorders: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Vandrey R. Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1967–1977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, O’Brien MS, Anthony JC. Who becomes cannabis dependent soon after onset of use? Epidemiological evidence from the United States: 2000-2001. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS. Classification and short-term course of DSM-IV cannabis, hallucinogen, cocaine, and opioid disorders in treated adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:995–1004. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Saha TD, Conway KP, Grant BF. The role of cannabis use within a dimensional approach to cannabis use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Swift W. Cannabis use disorder: Epidemiology and management. International Reviews of Psychiatry. 2009;21:96–103. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Earleywine M. Pothead or potsmoker? a taxometric investigation of cannabis dependence. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy. 2006;1:22. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Arif A, Hadgson R. Nomenclature and classification of drug- and alcohol-related problems: a WHO memorandum. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1981;59:225–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Gross M. Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. British Medical Journal. 1976;1:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G. The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome: a concept as stimulus to enquiry. British Journal of Addiction. 1986;81:171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Rounsaville B. Construct validity of the dependence syndrome as measured by DSM-IV for different psychoactive substances. Addiction. 1995;90:1661–1669. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901216618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Nelson E, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, True WR, Jacob T, Tsuang MT, Eisen SA. Shared genetic risk of major depression, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:1125–1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie NA, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Factor and item-response analysis DSM-IV criteria for abuse of and dependence on cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, sedatives, stimulants and opioids. Addiction. 2007;102:920–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Smith S, Saha TD, Huang B. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1351–1361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Neuman RJ, Todorov AA, Price RK, Bucholz KK. A comparison of the latent class structure of cannabis problems among adult men and women who have used cannabis repeatedly. Addiction. 2006;101:1133–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guxens M, Nebot M, Ariza C. Age and sex differences in factors associated with the onset of cannabis use: a cohort study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Teesson M, Lynskey M, Degenhardt L. The 12-month prevalence of substance use and ICD-10 substance use disorders in Australian adults: findings from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Addiction. 1999;94:1541–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Hart CL, Vosburg SK, Nasser J, Bennett A, Zubaran C, Foltin RW. Marijuana withdrawal in humans: effects of oral THC or divalproex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:158–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M. The marijuana withdrawal syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2005;7:360–366. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;14:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E. Substance use disorders: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) Addiction. 2006a;1:59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Liu X, Alderson D, Grant BF. DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a categorical or dimensional phenotype? Psychological Medicine. 2006b;36:1695–1705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Beseler CL. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol abuse, dependence, and binge drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF, Harford TC, Endicott J. The drug dependence syndrome and related disabilities. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Keyes KM, Alderson D, Wang S, Aharonovich E, Grant BF. Cannabis withdrawal in the United States: results from NESARC. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1354–1363. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Schuckit MA, Martin CS, Grant BF, Bucholz KK, Helzer JE. The validity of DSM-IV alcohol dependence: what do we know and what do we need to know? Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:244–252. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000060878.61384.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman GA, Ogburn E, Gorroochurn P, Keyes KM, Hasin D. Evidence for a two-stage model of dependence using the NESARC and its implications for genetic association studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer J, Bucholz KK, Gossop M. A dimensional option for the diagnosis of substance dependence in DSM-V. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16:S24–S33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell R, Brockington I. The identification of disease entities and the relationship between schizophrenic and affective psychoses. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:324–31. doi: 10.1192/bjp.137.4.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Geier T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Influence of a drinking quantity and frequency measure on the prevalence and demographic correlates of DSM-IV alcohol dependence. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Gardner CJ. Boundaries of major depression: an evaluation of DSM-IV criteria. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:172–177. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1992;13:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Hewitt BG, Grant BF. The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome, 30 years later: a commentary. Addiction. 2007;102:1522–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani JJ, Horey J, Bisaga A, Aharonovich E, Raby W, Cheng WY, Nunes E, Levin FR. Antisocial behavioral syndromes in cocaine and cannabis dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:405–414. doi: 10.1080/00952990802122473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenbucher JW. Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne BJ, Caspi A, Harrington H, Poulton R, Rutter M, Moffitt TE. Predictive value of family history on severity of illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:738–747. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CB, Rehm J, Ustun TB, Grant B, Chatterji S. Factor structures for DSM-IV substance disorder criteria endorsed by alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and opiate users: results from the WHO reliability and validity study. Addiction. 1999;94:843–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9468438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hope BT, Widnell KL. Drug addiction: a model for molecular basis of neural plasticity. Neuron. 1993;11:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90213-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawitan Y. All Likelihood: Statistical modeling and inference using likelihood. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Proposed changes in DSM-III substance use disorders: description and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143:463–468. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha T, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha T, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The role of alcohol consumption in future classifications of alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Saunders JB. The empirical basis of substance use disorders diagnosis: research recommendations for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V) Addiction. 2006;101:170–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, Grant BF. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift W, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Patton GC. Adolescent cannabis users at 24 years: trajectories to regular weekly use and dependence in young adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103:1361–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift W, Hall W, Teesson M. Characteristics of DSM-IV and ICD-10 cannabis dependence among Australian adults: results from the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M, Lynskey M, Manor B, Baillie A. The structure of cannabis dependence in the community. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]