Abstract

The identification of specific cell surface markers that can be used to isolate liver progenitor cells will greatly facilitate experimentation to determine the role of these cells in liver regeneration and their potential for therapeutic transplantation. Previously, the cell surface marker, CD24, was observed to be expressed on undifferentiated bipotential mouse embryonic liver stem cells and 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine-induced oval cells. Here, we describe the isolation and characterization of a rare, primary, nonhematopoietic, CD24+ progenitor cell population from normal, untreated mouse liver. By immunohistochemistry, CD24-expressing cells in normal adult mouse liver were colocalized with CK19-positive cholangiocytes. This nonhematopoietic (CD45−, Ter119−) CD24+ cell population isolated by flow cytometry represented 0.04% of liver cells and expressed several markers of liver progenitor/oval cells. The immunophenotype of nonhematopoietic CD24+ cells was CD133, Dlk, and Sca-1 high, but c-Kit, Thy-1, and CD34 low. The CD24+ cells had increased expression of CK19, epithelial cell adhesion molecule, Sox 9, and FN14 compared with the unsorted cells. Upon transplantation of nonhematopoietic CD24+ cells under the sub-capsule of the livers of Fah knockout mice, cells differentiated into mature functional hepatocytes. Analysis of X and Y chromosome complements were used to determine whether or not fusion of the engrafted cells with the recipient hepatocytes occurred. No cells were found that contained XXXY or any other combination of donor and host sex chromosomes as would be expected if cell fusion had occurred. These results suggested that CD24 can be used as a cell surface marker for isolation of hepatocyte progenitor cells from normal adult liver that are able to differentiate into hepatocytes.

Introduction

Mature adult hepatocytes can respond to hepatic injury, such as partial hepatectomy or hepato-specific toxins, to restore the mass of liver through cell proliferation. However, when hepatocyte replication is blocked, liver progenitor cells, called oval cells in rodents, are able to proliferate and differentiate into mature hepatocytes [1]. A number of different liver progenitor cell populations derived from adult liver have been reported [2–10]. Oval cells are considered to be transit amplifying cells and are reported to differentiate into both the hepatocytic and cholangiocytic lineages in vitro [11]. Liver progenitor/oval cells have been reported to express various cell surface markers in common with hematopoietic stem cells, such as Sca-1, c-Kit, Thy-1, and CD34 [12–15].

Tremendous effort has been made by several groups to identify new specific cell surface markers that are unique to adult liver stem/progenitor cells. Yovchev et al. carried out gene expression profiling of rat oval cells that were activated by 2-acetylaminofluorene treatment followed by partial hepatectomy [16]. Rat liver progenitor/oval cell surface markers such as CD133, CD24, epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCaM), and CD44 were identified, but the previously reported hematopoietic stem cell markers Thy-1, c-kit, and CD34 were absent. Subsequently, the repopulation capacity of EpCAM-positive oval cells into the injured rat liver indicated that the EpCAM-positive population contained bi-potential progenitors [9]. Of note, EpCAM was also found expressed on human hepatic stem cells (hHpSCs) [17]. Additionally, CD133 was shown to be a marker of mouse liver oval cells in animals that had undergone lineage-specific injury [18]. CD133-positive oval cells isolated from mice treated with DDC (3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine) and grown in vitro were able to engraft and express hepatocyte markers in vivo when transplanted into Fah (fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase) knockout mice, suggesting that CD133 might permit isolation of liver progenitor/oval cells, although transplantation without prior in vitro growth was not described [8].

Dorrell et al. used an unbiased cell immunization technique similar to that used to develop blood cell surface markers, to obtain differential labeling of normal and oval cells in the mouse. This procedure produced a panel of surface reactive monoclonal antibodies for oval cells [19]. Although the repopulation capacity of cells isolated by the reported monoclonal antibodies remains to be examined, these are very promising reagents that will be useful in the study of many aspects of liver biology.

Adult liver progenitor/oval cells share phenotypic characteristics with fetal liver stem/progenitor cells or hepatoblasts; both are proliferative, capable of bilineage differentiation, and express common marker genes (AFP, CK19, Dlk, and A6 antigen). These observations led to the speculation that oval cells may be a subset of undifferentiated fetal liver cells that remain in adulthood. To identify new surface markers for adult hepatic progenitor cells, we and others took advantage of fetal liver stem/progenitor cell lines that could be cultured in vitro and induced to differentiate into both hepatocyte-like and cholangiocyte-like cells. Using the powerful analytic tool of gene expression profiling, undifferentiated mouse embryonic fetal liver cells were compared with the differentiated counterparts or to adult liver cells [20,21]. A variety of potential cell surface markers were reported. Both groups reported that CD24 was highly expressed in undifferentiated fetal liver stem cells, but not in cells induced to the hepatocyte-like state. In addition, we showed that CD24 was specifically expressed on oval cells in the DDC-treated livers, which was in line with the finding that CD24 was expressed by oval cells activated by 2-acetylaminofluorene treatment followed by partial hepatectomy (2-AAF/PH) in rat liver [16].

Although a panel of cell surface markers has been described for adult liver progenitor/oval cells, to date, the repopulation capacity of cells isolated by those markers has been tested only in oval cell populations induced by carcinogenic agents such as DDC or by cells that have undergone in vitro expansion. Here we provide evidence that a rare, primary, nonhematopoietic cell population isolated by the cell surface marker, CD24, from normal, untreated adult, mouse liver differentiated into hepatocytes without apparent fusion after transplantation into livers of Fah knockout mice. These cells expressed previously identified liver progenitor/oval cell marker genes. These findings suggest that CD24 is a cell surface marker that can be used to isolate progenitor cells from normal, untreated adult liver and thus provide a tool for facilitating our understanding of the role of these cells in liver regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains and liver injury models

We are grateful to have obtained Fah knockout mice from Dr. Markus Grompe, which were used as transplantation recipients. Donor cells for transplantation were from untreated Rosa26LacZ mice (Jackson Laboratory). All Fah mutants were maintained on water containing 2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC) at a dose of 1 mg/kg (body weight)/day.

For induction of oval cells to be used in comparative immuno-characterizations, wild-type C57BL/6 mice were treated with DDC (0.1% wt/wt in PicoLab 5015 mouse chow) for 3 weeks. No transplantation studies were done with cells from DDC-treated animals. DDC was purchased from Sigma and a formulated diet containing 0.1% DDC was generated by TestDiet (Purina Mills, LLC).

Fah mutant and Rosa26LacZ mice were maintained in a C57BL/6/129 mixed background. Animal care and experiments were all in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunohistochemistry

Liver tissues were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) and 10 μm sections were cut and stored at −80°C till use. Frozen sections were fixed in ice-cold acetone for 5–10 min at room temperature. For double detection of CD24 and CK19 or single detection of either antibody, fixed sections were blocked with 10% mouse serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then with a block for endogenous biotin using the Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit (Vector Laboratories; SP-2001). For Fig. 3A Biotinylated monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD24 IgG2b antibody (BD Biosciences; 553260, 1:50) was incubated with sections overnight at 4°C and with Avidin D coupled to Texas Red (Vector Laboratories; A1100, 1:50) for 30 min at room temperature. Rat anti-mouse monoclonal anti-body CK19 IgG2a (TROMA III clone, a generous gift from Rolf Kemler at the Max-Planck Institute) (1:200) was subsequently incubated with sections. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse anti-rat IgG2a secondary antibody (Serotec; MCA278F, 1:100) was used to detect CK19 specifically. For individual antibody staining of A6 and CD24 (Fig. 3B), biotinylated monoclonal rat antimouse CD24a IgG2b antibody (BD Biosciences; 553260, 1:50) was used and the secondary antibody for CD24 was FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rat polyclonal antibody (1:200). Rat anti-mouse A6 antibody (1:200) was incubated with sections. FITC-conjugated donkey antirat polyclonal secondary antibody was used to detect A6. Slides were mounted with coverslips using Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Vector Laboratories; H-1200). All experiments included a negative control without primary antibody. The stained sections were examined using fluorescence microscopy.

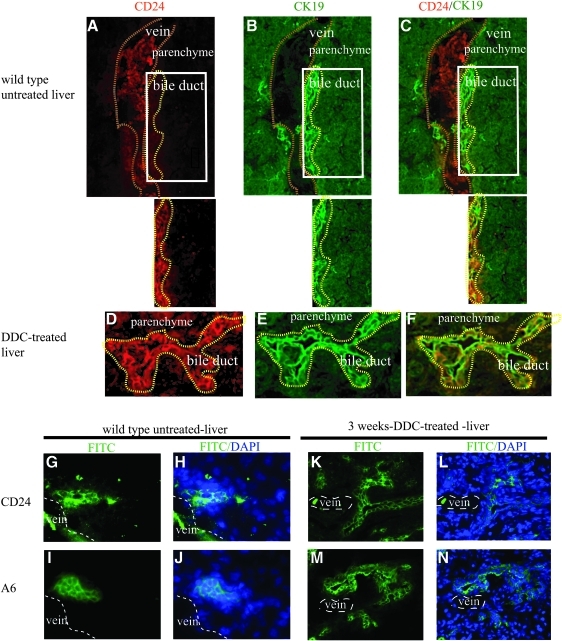

FIG. 3.

CD24 expression in normal, untreated, and DDC-treated liver. (A–F) Colocalization of CD24 and CK19 expression in wild-type untreated and DDC-treated livers. CD24 expression on bile duct epithelium was weak in untreated liver compared with red blood cells (A). Note that red blood cells in the vein (A) are strongly stained with CD24, but are CK19 negative in the merged view. To eliminate the high background signal from the red blood cells, the microscopic field was limited to the bile duct area outlined in yellow. The panel below each frame (A–C) shows staining of cells in ductular regions. CD24 (A, D, red) colocalized with CK19 (B, E, green) in the periportal zone in both untreated and DDC-treated liver (C, F). CD24 is induced in DDC-treated ductal cells (D), which correlated with the expansion of expression of CK19 (E). The magnification is 400×. (G–N) Immunohistochemical staining of CD24 and A6 antibodies on adjacent sections of normal wildtype and DDC-treated liver. In normal, untreated, wildtype liver, CD24 was expressed on red blood cells in the vein (labeled by lines) and ductal cells (G, H, green). In the same location of adjacent slides, A6 expression showed ductular staining similar to that of CD24 (I, J, green). In DDC-treated liver, the ductal expansion of CD24 expression (K, L, green) was similar to that of A6 (M, N, green). DNA is stained with DAPI blue. The magnification is 200×. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Rabbit FAH antibody (a gift from Dr. Markus Grompe) was incubated overnight at 4°C with frozen sections that were fixed in Zamboni fixation buffer (Newcomer supply; cat# 1459) for 30 min and blocked in 3% H2O2/PBS for 10 min and subsequently in Background Buster (Accurate; cat# H7988) for 30 min at room temperature. Then slides were incubated with Dako EnVision–labeled polymer antirabbit IgG (Dako; cat#K4002) for 30 min, and Romulin AEC chromogen (BioCare Medical; cat# RAEC810 L, M) was applied till the desired intensity was achieved. The sections were counterstained in hematoxylin and covered in Krystalon after dehydration in ethanol and xylene.

Rabbit Ki67 antibody (Novus; NB 110–8717) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min after fixation in 2% formalin/PBS and blocked with peroxidase blocking reagent and 2% goat serum. Antirabbit antibody (Vector; BA 1000) was incubated with the tissue and detected with the Vector Elite ABC kit, rinsed, and mounted with aqueous mounting medium.

Liver perfusion and cell separation

Livers from Rosa26LacZ adult animals (untreated) were perfused with 0.28 mg/mL collagenase IV (Sigma; C-5138) through the inferior vena cava. The dissociated cells were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer to remove clumps and undigested tissue. Cells were centrifuged mildly at 10 g for 5 min to pellet down hepatocytes and supernatant cells were collected by centrifugation at 350 g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in 90 μL of running buffer (PBS pH 7.2, 0.5% BSA, and 2 mM EDTA) per 107 cells, incubated with 10 μL each of anti-mouse CD45 and anti-mouse Ter119 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec; 130-052-301, 130-049-901) at 4°C for 15 min, and applied to an AutoMACS sorter (Miltenyi Biotec) to deplete CD45 and Ter119-positive cells. The suspension was then incubated with antibodies for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis and/or sorting.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

After depletion of CD45+ and Ter119+ cells using AutoMACS, the remaining population was incubated on ice for 10 min with antiCD24, antiCD45, and antiTer119 antibodies to isolate CD24+, CD45−, and Ter119− cells for transplantation. For FACS analysis, an additional antibody was added to the incubation (c-Kit, Thy-1, CD34, Dlk, CD133, or Sca-1). Fluorescence-conjugated antibodies purchased from BD Biosciences were CD24PE (553262), CD45FITC (553080), CD45APC (Allophycocyanin) (559864), Ter119FITC (557915), Ter119APC (557909), c-KitAPC (553356), Thy-1APC (553007), and CD34FITC (560238). DlkFITC was from MBL (D187-4), CD133APC was from (Miltenyi Biotec; 130-092-335), and Sca-1APC was from eBioscience (17-5981-81). Cells were washed once and suspended in Hank's balanced salt solution+[Hank's balanced salt solution, 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS)] medium with 2 μg/mL propidium iodide to discriminate dead from viable cells. Cells were analyzed and sorted by a Dako Cytometer. Positive and negative gates were determined by using IgG-isotype and unstained controls.

Cytospin

Sorted cells were resuspended in FBS:PBS (1:1) at a concentration of 105 cells/mL. Slides were placed in the cyto-centrifuge chamber (Shandon CytoSpin 4 cytocentrifuge) and 100–200 μL of cell suspension was added. About 50 μL of FBS:PBS solution was added to upper channel of cyto-centrifuge chamber. The cells were spun down at 500 rpm for 10 min using low acceleration. Slides were removed, air-dried, and fixed in ice-cold acetone for 5 min, followed by washing in water and air-drying for overnight if needed. Slides were store at −80°C until use.

RNA isolation

Total RNA from FACS-sorted cells and liver tissues was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy micro and mini kits. RNase-free DNase was used to digest DNA on-column according to the manufacturer's handbook.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was transcribed into cDNA by the SuperScript II RNase H Reverse transcription kit at 37°C for 60 min (Invitrogen). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted using cDNA, gene-specific primers, and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR was performed using the ABI Prism 7,000 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). PCR cycling conditions consisted of 95°C 30 s and 60°C 30 s for 40 cycles. Gene primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1 of supplementary results (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd). Data were analyzed using ABI Prism 7,000 SDS Software.

Transplantation

FACS-sorted cells isolated from untreated Rosa-26 donor livers were delivered under the liver sub-capsule of Fah knockout mice by a 10 μL Hamilton syringe. Donor cells wee transplanted immediately after isolation without a period of in vitro culture. The injection sites were labeled by India ink. The sex for donor and recipient was always different. Fah-deficient mice were maintained with NTBC-containing drinking water until transplantation. After transplantation, the mice received regular water for 2 weeks, returned to the NTBC for 4–6 days, and withdrawn again for 6–8 weeks after transplantation. The injected liver tissues were harvested and embedded in OCT, and stored at −80°C.

X-gal staining

For screening of X-gal-positive nodules, 10 μm frozen section was collected for X-gal staining and another four 5 μm sections were collected for antibody staining. Then, 200 μm was trimmed and started to another round of collection for X-gal and antibody staining. For X-gal staining, sections were fixed in X-gal fixation buffer (0.2% glutaradehyde, 2% PFA, 5 mM EDTA, and 2 mM MgCl2 in 0.1M phosphate buffer pH 7.3) for 2 min at room temperature. Slides were rinsed 3 times for 5 min each with 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.2% NP40, and 2 mM MgCl2 in 0.1M phosphate buffer pH 7.3 (rinse buffer). Then, slides were stained overnight with 1 mg/mL X-gal, 5 mM K ferricyanide, and 5 mM K ferrocyanide in Rinse buffer in the dark. Slides were rinsed again with rinse buffer, counterstained with nuclear fast red, and mounted with aqueous mounting medium.

X and Y chromosomes FISH assay

The bacterial artificial chromosome clones for chromosomes X (RP23-298N24) and Y (RP24-241O12) were labeled by nick translation using Spectrum red and Spectrum green (Abbott Laboratories), respectively. Hybridization and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed as described previously [22]. The slides were counterstained with DAPI, and the images were captured using Nikon E-800 microscope equipped with Quips Pathvysion (Applied Imaging).

Results

Isolation of CD24+ cells from normal adult liver by FACS

CD24 is known to be expressed by erythrocytes and myeloid lineage. Based on our previous observations that cells expressing CD24 did not express the pan-hematopoietic marker CD45 [20], we chose to isolate primary CD24+ cells from normal untreated liver in CD45 and Ter119 (erythrocyte marker) negative populations. Hereafter, this nonhematopoietic (CD45−, Ter119−) CD24+ cells are referred to as CD24+ cells.

To isolate primary CD24+ cells from normal untreated adult liver, a serial enrichment protocol was developed using perfusion of the liver followed by centrifugation and FACS (Fig. 1A). Hepatocytes constitute ∼60% of the cells in the liver. To enrich for nonparenchymal cells following perfusion, we employed a low-speed (10 g for 5 min) centrifugation to preferentially pellet hepatocytes. This step removed 48% of the cells, which were mainly hepatocytes, and enriched for the nonparenchymal cells (cholangiocytes, Kupffer cells, stellate cells, hematopoietic cells, and endothelial cells) and putative progenitors in the supernatant. The supernatant was partially depleted CD45- and Ter119-expressing cells by AutoMacs and then was sorted based on expression of CD24, CD45, and Ter119.

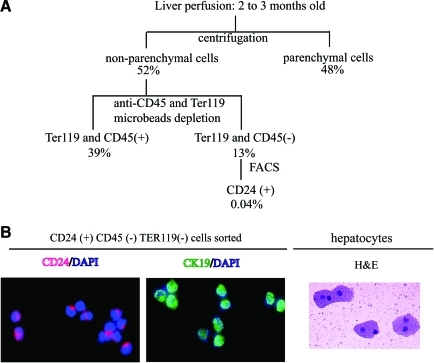

FIG. 1.

Strategy for isolation of CD24+ cells from normal untreated liver. (A) Schematic representation of the strategy for the isolation of CD24+ cells. The percentage yield of each population compared with the starting number of cells after liver perfusion is shown. (B) Immunostaining of CD24 and CK19 on isolated CD24+ cells. FACS-sorted cells were cytospun onto the slides. Eighty-nine percent of cells were CD24 positive (red) and 60% of cells were CK19 positive (green). DAPI (blue) stains nuclei. Cytospun hepatocytes stained with hematoxylin and eosin were larger than CD24 cells. The magnification is 400× for all 3 panels. DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

FACS-sorted CD24+ cells were cytospun onto slides, stained with DAPI, and either antiCD24 or antiCK19 antibody. Eighty-nine percent of cells were CD24 positive (red) and 60% were CK19 positive (green) (Fig. 1B, left and center panels, 100×). The morphology of these cells was different from cytospun hepatocytes (stained with hematoxylin and eosin, 100×, Fig. 1B, right panel) and of smaller size. Some of the hepatocytes are binucleate, a typical property of this cell type.

From the side and forward scatter data (Fig. 2A left panel) of live cells (judged by a lack of propidium iodide staining), the cells were gated into 3 groups. Gate 1 was composed of cell debris. Gate 2 contained dying and live hepatocytes (based on cell size and trypan blue staining of sorted cells, data not shown). Gate3 was composed of viable and relative smaller size cells. To reduce contamination of large cells (which include hepatocytes) and enrich for putative progenitors of smaller size, Gate 3 was chosen to sort cells based on CD24, CD45, and Ter119 expression. The middle panel of Fig. 2A shows the nonhematopoietic CD24+ cells formed a tight group of cells that were clearly distinguished from nonhematopoietic (CD45−, Ter119−) CD24− cells (hereafter referred to as CD24−) and hematopoietic (CD45+, Ter119+) cells.

FIG. 2.

Isolation of CD24+ cells by FACS. (A) Representative FACS sorting plot of nonparenchymal cells depleted for CD45+ and Ter119+ cells. The gate 3 (G3) cells in the left panel were selected to isolate CD24-positive cells. In the G3 population (middle panel), CD24-positive, CD45−, Ter119− (CD24+) cells were clearly separated from CD24 negative (CD24−) cells and from CD24+, CD45+, and Ter119+ population. In the right panel, the side scatter versus forward scatter of CD24+ cells is shown. The spread of CD24+ cells along forward scatter axis indicates that the size of CD24+ cells is variable. The gate used to select CD24+ cells and CD24− cells was based on the negative unstained control. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of CD24, CK19, and EpCAM expression in FACS-isolated CD24+ cells showed reduced levels in the untreated wild-type cell population compared with that from the DDC-treated liver. DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; EpCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Calculating back to the starting cell population, nonhematopoietic CD24+ cells accounted for 0.04% of all the cells obtained by perfusion of the liver and are a relatively rare population in the normal adult liver.

CD24 expression was detected in ductal cells of untreated and DDC-treated livers

We investigated CD24 expression by immunostaining of the livers from untreated and DDC-treated wild-type animals. Immunostaining of frozen sections of normal adult liver using the CD24 antibody identified a relatively rare population of CD24-positive cells located in region of the ductular epithelial cells. To examine coexpression of CD24 and CK19 (a marker for cholangiocytes and oval cells), a biotinylated monoclonal rat antimouse CD24a IgG2b antibody was used that could be distinguished from the rat antimouse monoclonal antibody CK19 IgG2a (see Materials and Methods section). The signal of CD24 expression was very strong in red blood cells located in the lumen of the vein (outlined by dotted lines), relatively weak in normal cholangiocytes and absent in hepatocytes (Fig. 3A–C). Isolating the microscopic field to the bile duct region (in the panel below Fig. 3A–C) shows CD24-positive bile duct epithelial cells. The signal of CD24 expression colocalized with CK19-positive cholangiocytes and was distinct from the surrounding hepatocytes (Fig. 3A–C). Immunohistochemical staining of hepatic oval cell marker A6 and CD24 on the adjacent sections of normal untreated liver showed that CD24-positive ductal cells may also express A6 (Fig. 3G–J).

CD24 expression was strongly induced in the liver after 3 weeks of treatment by DDC (Fig. 3D). The colocalization of CD24 and CK19 expression in DDC-treated liver revealed that CD24 was expressed on expanding primitive ductal cells (Fig. 3E, F). The ductular expression of CD24 in DDC-treated liver showed a similar pattern to that of the oval cell marker A6 in an adjacent tissue section (Fig. 3K–N).

Subsequent qPCR analysis of sorted primary, nonhematopoietic, CD24+ cells from livers of untreated, and DDC-treated mice showed that the expression of CD24 was upregulated more than 5-fold in DDC-treated cells compared with CD24+ cells in untreated livers, whereas expression of CK19 and EpCAM showed an increase of less than double and 2.6-fold, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Expression of marker genes of cholangiocytes, stellate cells, and Kupffer cells in CD24+ cells

To determine the purity of sorted CD24+ cells, immunohistochemical analysis was performed for cell-type-specific markers, including desmin and F4/80 on cytospun CD24+ cells isolated by FACS as described above. As just shown in Fig. 1B, 89% of cells were CD24 positive, 60% were positive for CK19, a cholangiocyte marker, but only 0.005% cells were positive for the stellate cell marker desmin, and no cell was positive for F4/80, a macrophage cell marker (data not shown). These results indicated that CD24+ cells isolated as described were enriched for cells expressing markers for cholangiocytes, but not for stellate cells that were previously identified as liver progenitor cells [5,23] and there was little or no contamination of hematopoietic macrophage cells, which were reported to be able to repopulate the liver in Fah knockout mice by fusion with resident hepatocytes [24].

It was observed that <1% of cells in the CD24+ cell population were larger cells (diameter around 20–25 μm) with increased nuclear size that could have been hepatocytes based on morphology. However, when these larger cells were assessed by Trypan Blue Dye exclusion for viability, they took up the dye and were judged to be nonviable (data not shown).

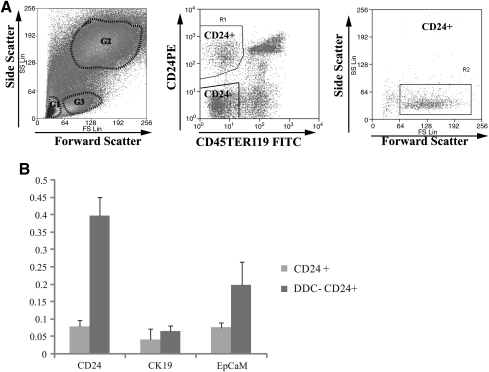

Expression of liver progenitor markers by CD24+ cells

To know whether CD24+ cells from normal, untreated adult liver were similar to previously reported liver progenitor/oval cells, we assessed several markers by FACS and real-time PCR. These included the cell surface protein, CD133, first identified as a hematopoietic stem cell marker, was reported to be expressed on stellate cells [5] and identified as a marker for normal cholangiocytes and DDC-induced oval cells [8,18]; Dlk-1, a type-I membrane protein, which was demonstrated to be expressed on hepatoblasts in embryonic liver [25] and transit-amplifying oval cells [25,26]; Sca-1 and CD34, hematopoietic stem cell markers, also reported to be markers of liver oval cells [12]. Thy-1, previously thought to express on oval cells, was found on myofibroblast/stellate cells, adjacent to oval cells [27]. The expression of c-kit on oval cells is still controversial [18,28]. Immunophenotypic analysis of the above markers on CD24+ cells showed that a high percentage expressed CD133 (89%), Dlk (80%), and Sca-1 (80%), but few cells expressed Thy-1 (3%), CD34 (3%), and c-Kit (0.5%) (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Expression of previously reported liver progenitor cell markers. (A) A representative immunophenotypic analysis of CD24+ cells by FACS. The percentage of the CD24+ cells that were positive for each antigen tested is shown in the right top corner. CD24+ cells have a high concordance with CD133, Sca-1, and Dlk-positive cells, whereas c-Kit, Thy-1, and CD34 are virtually absent in CD24+ cells. The gate was chosen based on the negative unstained control. The percentage was the mean acquired from 3 independent experiments. (B) Real-time PCR expression of CD24, EpCAM, CK19, Sox9, Fn14, CD133, Abcg2, Hnf4, c-Kit, and Thy-1 in CD24+ cells (dark black bar) compared with unsorted (light gray bar) and CD24− cells (gray bar). The expression level of each gene in the CD24+ and the CD 24− populations was compared with the level in unsorted cells, which was set to 1. RT-PCR data were the mean from 3 independent experiments, each test performed in triplicate, with fold change in log 10 base. APC, allophycocyanin.

Liver progenitor/oval cell marker expression was also examined at mRNA level in the same 3 cell populations (CD24+, CD24−, and unsorted cells) from normal untreated liver (Fig. 4B). First of all, CD24 expression was examined. CD24 expression level in CD24+ cells showed a 100-fold increase over that in the CD24− and the unsorted cell populations, suggesting that flow-sorted CD24+ cells were indeed enriched for CD24-expressing cells.

Second, previously reported oval cell markers such as EpCaM, CK19, Fn14, CD133, Abcg2, c-Kit, and Thy-1 were examined. EpCaM, a marker for isolation of hepatic stem cells from human liver and oval cells from the rat liver [9,17], was highly expressed (100-fold) in CD24+ cells over CD24− and unsorted cells. CK19 expression was nearly 90-fold higher in CD24+ cells versus CD24− and unsorted cells, which is also consistent with IHC results (Fig. 1B). Since CK19 is not only a progenitor cell marker [14], but also a marker for cholangiocytes, we tested another cholangiocyte marker, Sox9 [29], for expression in the CD24+ pool. Sox9 expression was also highly elevated (20-fold) in CD24+ cells, showing that the CD24+ population shares 2 markers of cholangiocytes. Fn14, the TWEAK (TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis) receptor, which was found expressed on oval cells [30], was over 10-fold greater in CD24+ cells compared with the other 2 populations, whereas expression of CD133 was 70-fold greater in the CD24+ cells compared with the CD24− cells and 7-fold greater than unsorted cells. Abcg2, a marker for the side population phenotype reported initially in hematopoietic stem cells [31–33] and also found in diverse adult tissue progenitor cells [34–37] including hepatic oval cells [38], was less highly expressed in CD24+ cells than the unsorted cells from normal adult liver. The expression of c-Kit and Thy-1 was very low (10-fold less) in CD24+ versus the unsorted cells, which was consistent with the FACS analysis of those markers.

In addition, hepatocyte markers, albumin and Hnf4, were elevated in the unsorted cell fraction consistent with that pool having mature hepatocytes present. Neither CD24+ cells nor CD24− cells expressed significant amounts of these two hepatocyte-specific genes. The expression of α-FP, desmin, CD4, and CD8 was not detectable in CD24+ cells (data not shown).

Taken together, these results indicate that the CD24+ pool isolated from normal adult liver shares expression of several liver progenitor/oval cell markers.

CD24+ cells engraft and differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo

We next tested whether FACS-sorted CD24+ cells isolated from normal, uninjured Rosa26LacZ livers could reconstitute hepatic tissues in vivo by sub-capsular injection into the livers of Fah null mice of a different gender from that of the donor. CD24+ cells isolated from RosaLacZ mice (detectable by staining for β-galactosidase activity) were transplanted into Fah knockout mouse livers and the recipient animals were cycled on NTBC free or supplemented water for several weeks, ranging from 4 to 6 as described in the Materials and Methods section, to achieve a selective advantage for transplanted cells. The livers were harvested from the Fah knockout recipient mice and screened by X-gal staining of sections at intervals of ∼100 μm through the injected lobe (Fig. 5A). Engrafted X-gal-positive nodules were observed in 3 out of 8 (37.5%) transplanted mice. Table 1 shows the numbers of animals injected and the frequency of engraftment and X-gal-positive nodules. The average number of cells in the engrafted nodules on one 10 μm section is about 100 cells. The clusters ranged from 100 to 790 μm in depth as measured with serial sections described in Materials and Methods. Based on the average diameter of mature hepatocytes about 25 μm, the number of engrafted cells was estimated to range from 2,160 to 10,000 cells.

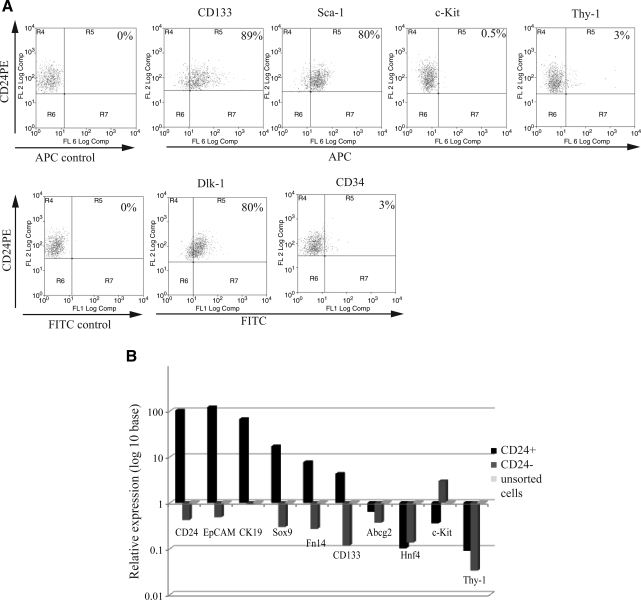

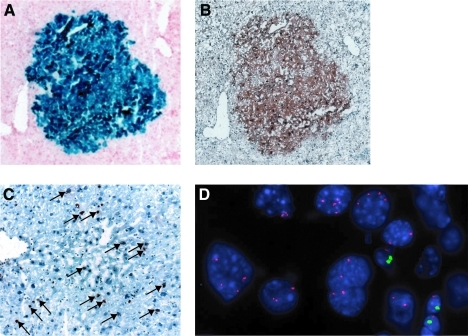

FIG. 5.

CD24+ cells integrated and proliferated in the liver of FAH knockout mice. (A) X-gal staining shows a blue cluster of X-gal-positive cells in the recipient parenchyma. (B) Immunostaining of FAH (brown) on the adjacent serial section shows that the X-gal-positive cells are also FAH positive. (C) The clusters of X-gal- and FAH-positive cells are composed of proliferating cells as shown by the nuclear staining of Ki67 in an adjacent section (arrows indicate the positive staining). (D) X and Y chromosomes FISH assay on the engrafted nodule. In this case, the donor was from a female and the recipient was a male. Both tetraploid and diploid female cells are seen in the large hepatocyte nuclei. The size of the XY-containing cells of the recipient suggests that these may be infiltrating lymphocytes. FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Table 1.

Liver Engraftment of CD24 Cells

| Type of transplanted cells | No. of transplanted cells | No. of transplanted lobes and injection sites | No. of lobes with X-gal positive | No. of clusters and total engrafted cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD24+ | 56,500 | 1 lobe, 3 sites | 1 | 11 clusters 10,000 cells |

| CD24+ | 75,591 | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 0 | 0 |

| CD24+ | 100,143 | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 2 | #1 lobe: 4 clusters 9,520 cells |

| #2 lobe: 2 clusters 2,160 cells | ||||

| CD24+ | 54,933 | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 0 | 0 |

| CD24+ | 78,974 | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 1 | 6 clusters 5,440 cells |

| CD24+ | 80,614 | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 0 | 0 |

| CD24+ | 50,000 | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 0 | 0 |

| CD24+ | 50,000 | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 0 | 0 |

| CD24− | 50,000 each for 5 mice | 2 lobes, 4 sites For each mouse | 0 | 0 |

| CD24− | 100,000 each for 5 mice | 2 lobes, 4 sites | 0 | 0 |

The X-gal-positive engrafted cells were also positive for FAH antibody staining (Fig. 5B), confirming that the engrafted cells were derived from the Fah+/+ Rosa-26 donor and were functional, mature hepatocytes. CD24 expression was lost in the engrafted nodules (data not shown). The engrafted cells had a high rate of division as determined by immunostaining for Ki67, a marker of cell proliferation (Fig. 5C). As a control, 10 animals were transplanted with CD24− cells from Rosa26LacZ donors. Five mice received 50,000 cells and 5 mice received 100,000 cells. None had any X-gal-positive nodules after NTBC cycling.

As confirmation that the engrafted cells were from the donor and because bone marrow and macrophage cells have been shown to fuse with the resident hepatocytes [24,28,39], we tested whether engrafted CD24+ cells were the results of fusion with recipient hepatocytes. A fused cell would express donor traits (X-gal, FAH, and the sex chromosomes of the donor) and the recipient sex chromosome complement. Therefore, we took advantage of a chromosome-specific FISH assay to examine the X-gal-positive nodules for their complement of X and Y chromosome. Having used donors and recipients of the opposite sex, we could distinguish any cells that had the combined complement of parental chromosomes as a fused cell. We counted the number of X and Y chromosomes in 3 X-gal-positive clusters from independent transplantations as well as the number of X and Y chromosomes of the host cells that were located adjacent to the engrafted clusters (Table 2). In engrafted clusters, a total of 274 cells were counted (101, 82, and 91 cells from 3 independent transplantation clusters, respectively); none was found with an XXXY karyotype. Indeed, the vast majority of engrafted cells had the chromosomal complement of the donor (88%–100%). Of the total number of cells scored, 8 (8/278=2.87%) had an XXX karyotype and could have originated from fusion between donor and host. In addition, 23 cells (5.5%) contained 1X, 1Y, or had no chromosome signal. It is likely that these 23 cells reflect the plane of the section that may have excluded one, or both members of the sex chromosome pair. In the regions adjacent to the engrafted clusters, a total of 284 cells were counted (93, 104, and 87 cells counted from 3 recipients). No cells had the karyotype of the donor or had an XXXY karyotype. Figure 5D shows an example of cells from a female donor engrafted within a male host. The cells in the engrafted nodule with large nuclei, typical of hepatocytes were XX, whereas the host cells with smaller nuclei (possibly inflammatory cells seen in Fah null mice) were XY (X: red, Y: green).

Table 2.

The Sex Chromosome Composition of Hepatocytes in Engrafted Clusters and Adjacent Host Cells

| Donor sex | Recipient sex | Total cells counted | Cells with n(XY) (tetraploid/diploid) | Cells with n(XX) (tetraploid/diploid) | Cells with n(XXXY) | Cells with n(XXX) | Cells undetermineda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster1 | XX | XY | 101 | 0 | 94 (29/65) | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Cluster2 | XY | XX | 82 | 72 (25/47) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| Cluster3 | XY | XX | 91 | 85 (35/50) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Outside of cluster1 | XX | XY | 93 | 87 (70/17) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Outside of cluster2 | XY | XX | 104 | 0 | 93 (71/22) | 0 | 2 | 11 |

| Outside of cluster3 | XY | XX | 87 | 0 | 82 (51/31) | 0 | 0 | 5 |

Undetermined means cells bear either 1X, or 1Y or no X and Y chromosome signals at all.

Thus, these results clearly showed that CD24+ cells can differentiate into morphologically mature hepatocytes expressing the liver gene, Fah, in vivo with no evidence of cells containing the XXXY karyotype, or other combination of donor and host sex chromosomes that would be expected if cell fusion had occurred.

Discussion

We report herein that a nonhematopoietic cell population of progenitor cells in normal, untreated, adult mouse liver can be isolated by the cell surface marker CD24. Previous publications have described engraftment and differentiation of cells either isolated from injured (chemical or surgical) livers or isolated from normal adult or fetal livers and then passaged in vitro before transplantation. Our study established that primary cells from normal untreated livers are capable of differentiation into hepatocytes following transplantation without toxin injury or in vitro manipulation that has the potential to alter cell proliferation pathways [40].

CD24, a GPI-anchored cell surface protein, was found to be expressed by several cell types, including hematopoietic cell sub-populations (B cells, T cells, and granulocytes) and nonhematopoietic cells such as neural stem/progenitor cells in the developing brain, regenerating muscle cells and differentiating keratinocytes [41,42]. The Canal of Hering is thought to be the compartment in which liver progenitor/oval cells reside. In the present study, we found that CD24 expression colocalized with the bile duct epithelial cell marker CK19 in the periportal area of mouse adult normal liver. Those cells also expressed hepatic oval cell antigen A6. Whether cells in the canal of hering express CD24 needs further examination. However, similar ductal expansion of CD24, CK19, and A6 in DDC-treated liver supported previous observations regarding oval cell expansion from the bile duct epithelial compartment following injury [43].

In nonliver cell types (adult brain stem/progenitor cells, skin, and cornea self-renewing epithelial cells), gain and loss of CD24 function may contribute to the production of differentiated cells by controlling the proliferation and differentiation balance between transit-amplifying and committed differentiated cells [42]. Although CD24 knockout mice were not reported to have alterations in liver development, it is possible that the CD24 deletion may affect the response to liver damage.

The phenotype of CD24+ liver cells in the normal adult mouse is similar to the reports by Yovchev et al. [9,16] in rats injured liver as they were enriched for CD133 (89%), Sca-1 (80%), and Dlk-1 (80%), whereas few expressed c-Kit (0.5%), Thy-1 (3%), or CD34 (3%). Real-time PCR analysis of rat oval cells showed that CD24+ cells expressed EpCAM, CK19, and Fn14. Thus, the phenotype of mouse CD24+ cells shows significant similarities to that of oval cells characterized by others [8,9,16,18].

It has been reported that bone marrow and myelomonocytes can undergo cell fusion with hepatocytes when transplanted into the liver. When bone marrow-derived cells were used as the donor population, the resulting hepatocyte-like nodules were virtually all derived from fusion events of monocytic cells and recipient hepatocytes [44]. Different groups have reported similar frequencies of cell fusion in studies of bone marrow-derived hepatocytes [24,28,45]. We used animals of different gender as the transplantation donor and recipient and employed in situ hybridization for X and Y chromosomes to distinguish the origin of engrafted cells and to determine whether the engrafted CD24+ cells fused with the recipient hepatocytes. From an analysis of multiple clusters from 3 different transplanted animals, no evidence of cell fusion products was found. Although cell fusion cannot be excluded in the small percentage of engrafted cells with an XXX karyotype, the data suggest that fusion and ploidy reduction, if it occurred at all, was not a major source of the hepatocytes in engrafted nodules.

Although we detected donor-derived clusters of hepatocytes, we did not detect engrafted bile duct epithelial cells. Fah is expressed primarily in hepatocytes and there is no direct injury to the bile duct epithelium in this model. Therefore, there is little or no selection for engraftment of donor cells in the cholangiocyte compartment. Consequently, our experiments do not address whether the CD24+ population has the ability to become bile duct epithelial cells in vivo.

In adulthood, CD24 is not detected by IHC in the mature hepatocytes, but is present in the adjacent CK19-positive cholangiocytes. Moreover, after transplantation of CD24+ cells, we found that CD24 expression was lost in the clusters of mature hepatocytes engrafted into the liver of Fah knockout mice. The decline in CD24 expression during maturation of hepatocytes was in line with the report that CD24 expression was detected on the fetal liver stem/progenitor cells, but not on mature hepatocytes by FACS analysis [21]. The loss of CD24 in the developing liver may support the speculation that the adult liver stem/progenitor cells described herein were from a subset of embryonic stem/progenitor cells that may have remained undifferentiated through adulthood.

In summary, CD24 is a cell surface marker for the isolation of normal adult mouse liver progenitor cells. This finding will facilitate the purification of a liver progenitor population that has not been subjected to toxic chemicals or in vitro culture conditions and will permit experimental characterization of this normal progenitor cell type.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by NIH AG028865. Administrative support was provided by Debra Meyer.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lazaro CA. Rhim JA. Yamada Y. Fausto N. Generation of hepatocytes from oval cell precursors in culture. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5514–5522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li WL. Su J. Yao YC. Tao XR. Yan YB. Yu HY. Wang XM. Li JX. Yang YJ. Lau JT. Hu YP. Isolation and characterization of bipotent liver progenitor cells from adult mouse. Stem Cells. 2006;24:322–332. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrera MB. Bruno S. Buttiglieri S. Tetta C. Gatti S. Deregibus MC. Bussolati B. Camussi G. Isolation and characterization of a stem cell population from adult human liver. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2840–2850. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuchiya A. Heike T. Baba S. Fujino H. Umeda K. Matsuda Y. Nomoto M. Ichida T. Aoyagi Y. Nakahata T. Long-term culture of postnatal mouse hepatic stem/progenitor cells and their relative developmental hierarchy. Stem Cells. 2007;25:895–902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kordes C. Sawitza I. Muller-Marbach A. Ale-Agha N. Keitel V. Klonowski-Stumpe H. Haussinger D. CD133+ hepatic stellate cells are progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conigliaro A. Colletti M. Cicchini C. Guerra MT. Manfredini R. Zini R. Bordoni V. Siepi F. Leopizzi M. Tripodi M. Amicone L. Isolation and characterization of a murine resident liver stem cell. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:123–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirata M. Amano K. Miyashita A. Yasunaga M. Nakanishi T. Sato K. Establishment and characterization of hepatic stem-like cell lines from normal adult rat liver. J Biochem. 2009;145:51–58. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki A. Sekiya S. Onishi M. Oshima N. Kiyonari H. Nakauchi H. Taniguchi H. Flow cytometric isolation and clonal identification of self-renewing bipotent hepatic progenitor cells in adult mouse liver. Hepatology. 2008;48:1964–1978. doi: 10.1002/hep.22558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yovchev MI. Grozdanov PN. Zhou H. Racherla H. Guha C. Dabeva MD. Identification of adult hepatic progenitor cells capable of repopulating injured rat liver. Hepatology. 2008;47:636–647. doi: 10.1002/hep.22047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright N. Samuelson L. Walkup MH. Chandrasekaran P. Gerber DA. Enrichment of a bipotent hepatic progenitor cell from naive adult liver tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fausto N. Campbell JS. The role of hepatocytes and oval cells in liver regeneration and repopulation. Mech Dev. 2003;120:117–130. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen BE. Grossbard B. Hatch H. Pi L. Deng J. Scott EW. Mouse A6-positive hepatic oval cells also express several hematopoietic stem cell markers. Hepatology. 2003;37:632–640. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X. Foster M. Al-Dhalimy M. Lagasse E. Finegold M. Grompe M. The origin and liver repopulating capacity of murine oval cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11881–11888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734199100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen BE. Zajac VF. Michalopoulos GK. Hepatic oval cell activation in response to injury following chemically induced periportal or pericentral damage in rats. Hepatology. 1998;27:1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosby HA. Kelly DA. Strain AJ. Human hepatic stem-like cells isolated using c-kit or CD34 can differentiate into biliary epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:534–544. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yovchev MI. Grozdanov PN. Joseph B. Gupta S. Dabeva MD. Novel hepatic progenitor cell surface markers in the adult rat liver. Hepatology. 2007;45:139–149. doi: 10.1002/hep.21448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmelzer E. Zhang L. Bruce A. Wauthier E. Ludlow J. Yao HL. Moss N. Melhem A. McClelland R. Turner W. Kulik M. Sherwood S. Tallheden T. Cheng N. Furth ME. Reid LM. Human hepatic stem cells from fetal and postnatal donors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1973–1987. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rountree CB. Barsky L. Ge S. Zhu J. Senadheera S. Crooks GM. A CD133-expressing murine liver oval cell population with bilineage potential. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2419–2429. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorrell C. Erker L. Lanxon-Cookson KM. Abraham SL. Victoroff T. Ro S. Canaday PS. Streeter PR. Grompe M. Surface markers for the murine oval cell response. Hepatology. 2008;48:1282–1291. doi: 10.1002/hep.22468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochsner SA. Strick-Marchand H. Qiu Q. Venable S. Dean A. Wilde M. Weiss MC. Darlington GJ. Transcriptional profiling of bipotential embryonic liver cells to identify liver progenitor cell surface markers. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2476–2487. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nierhoff D. Levoci L. Schulte S. Goeser T. Rogler LE. Shafritz DA. New cell surface markers for murine fetal hepatic stem cells identified through high density complementary DNA microarrays. Hepatology. 2007;46:535–547. doi: 10.1002/hep.21721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh L. Matsukuma S. Jones KW. Testis development in a mouse with 10% of XY cells. Dev Biol. 1987;122:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L. Jung Y. Omenetti A. Witek RP. Choi S. Vandongen HM. Huang J. Alpini GD. Diehl AM. Fate-mapping evidence that hepatic stellate cells are epithelial progenitors in adult mouse livers. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2104–2113. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willenbring H. Bailey AS. Foster M. Akkari Y. Dorrell C. Olson S. Finegold M. Fleming WH. Grompe M. Myelomonocytic cells are sufficient for therapeutic cell fusion in liver. Nat Med. 2004;10:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nm1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanimizu N. Nishikawa M. Saito H. Tsujimura T. Miyajima A. Isolation of hepatoblasts based on the expression of Dlk/Pref-1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1775–1786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen CH. Jauho EI. Santoni-Rugiu E. Holmskov U. Teisner B. Tygstrup N. Bisgaard HC. Transit-amplifying ductular (oval) cells and their hepatocytic progeny are characterized by a novel and distinctive expression of delta-like protein/preadipocyte factor 1/fetal antigen 1. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1347–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63221-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dezso K. Jelnes P. Laszlo V. Baghy K. Bodor C. Paku S. Tygstrup N. Bisgaard HC. Nagy P. Thy-1 is expressed in hepatic myofibroblasts and not oval cells in stem cell-mediated liver regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1529–1537. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X. Willenbring H. Akkari Y. Torimaru Y. Foster M. Al-Dhalimy M. Lagasse E. Finegold M. Olson S. Grompe M. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;422:897–901. doi: 10.1038/nature01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antoniou A. Raynaud P. Cordi S. Zong Y. Tronche F. Stanger BZ. Jacquemin P. Pierreux CE. Clotman F. Lemaigre FP. Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2325–2333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakubowski A. Ambrose C. Parr M. Lincecum JM. Wang MZ. Zheng TS. Browning B. Michaelson JS. Baetscher M. Wang B. Bissell DM. Burkly LC. TWEAK induces liver progenitor cell proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2330–2340. doi: 10.1172/JCI23486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spangrude GJ. Scollay R. A simplified method for enrichment of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 1990;18:920–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf NS. Kone A. Priestley GV. Bartelmez SH. In vivo and in vitro characterization of long-term repopulating primitive hematopoietic cells isolated by sequential Hoechst 33342-rhodamine 123 FACS selection. Exp Hematol. 1993;21:614–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodell MA. Brose K. Paradis G. Conner AS. Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1797–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redvers RP. Li A. Kaur P. Side population in adult murine epidermis exhibits phenotypic and functional characteristics of keratinocyte stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13168–13173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602579103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L. Hu J. Hong TP. Liu YN. Wu YH. Li LS. Monoclonal side population progenitors isolated from human fetal pancreas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oyama T. Nagai T. Wada H. Naito AT. Matsuura K. Iwanaga K. Takahashi T. Goto M. Mikami Y. Yasuda N. Akazawa H. Uezumi A. Takeda S. Komuro I. Cardiac side population cells have a potential to migrate and differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:329–341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds SD. Shen H. Reynolds PR. Betsuyaku T. Pilewski JM. Gambelli F. Di Giuseppe M. Ortiz LA. Stripp BR. Molecular and functional properties of lung SP cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L972–L983. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00090.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimano K. Satake M. Okaya A. Kitanaka J. Kitanaka N. Takemura M. Sakagami M. Terada N. Tsujimura T. Hepatic oval cells have the side population phenotype defined by expression of ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2/BCRP1. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:3–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63624-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vassilopoulos G. Wang PR. Russell DW. Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature. 2003;422:901–904. doi: 10.1038/nature01539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tirnitz-Parker JE. Tonkin JN. Knight B. Olynyk JK. Yeoh GC. Isolation, culture and immortalisation of hepatic oval cells from adult mice fed a choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented diet. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:2226–2239. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calaora V. Chazal G. Nielsen PJ. Rougon G. Moreau H. mCD24 expression in the developing mouse brain and in zones of secondary neurogenesis in the adult. Neuroscience. 1996;73:581–594. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nieoullon V. Belvindrah R. Rougon G. Chazal G. Mouse CD24 is required for homeostatic cell renewal. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;329:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paku S. Schnur J. Nagy P. Thorgeirsson SS. Origin and structural evolution of the early proliferating oval cells in rat liver. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camargo FD. Finegold M. Goodell MA. Hematopoietic myelomonocytic cells are the major source of hepatocyte fusion partners. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1266–1270. doi: 10.1172/JCI21301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alvarez-Dolado M. Pardal R. Garcia-Verdugo JM. Fike JR. Lee HO. Pfeffer K. Lois C. Morrison SJ. Alvarez-Buylla A. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.