Abstract

AIM: To compare the presentation and impact on quality of life of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in old and young age groups.

METHODS: Data from adult patients with GERD diagnosed by endoscopic and symptomic characteristics were collected between January and November 2009. Exclusion criteria included combined peptic ulcers, malignancy, prior surgery, antacid medication for more than 2 mo, and pregnancy. Enrolled patients were assigned to the elderly group if they were 65 years or older, or the younger group if they were under 65 years. They had completed the GERD impact scale, the Chinese GERD questionnaire, and the SF-36 questionnaire. Data from other cases without endoscopic findings or symptoms were collected and these subjects comprised the control group in our study.

RESULTS: There were 111 patients with GERD and 44 normal cases: 78 (70.3%) and 33 patients (29.7%) were in the younger and elderly groups, respectively. There were more female patients (60.3%) in the younger group, and more males (72.7%) in the elderly group. The younger cases had more severe and frequent typical symptoms than the elderly patients. Significantly more impairment of daily activities was noted in the younger patients compared with the elderly group, except for physical functioning.

CONCLUSION: Elderly patients with GERD were predominantly male with rare presentation of typical symptoms, and had less impaired quality of life compared with younger patients in a Chinese population.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Quality of life, Age factors

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic disease which has a considerable, impact on the everyday lives of affected individuals, and interferes with physical activity, impairs social functioning, disturbs sleep and reduces productivity at work[1]. The prevalence of the disease increases with age[2,3], and advanced age has been identified as a significant risk factor for relapse of esophagitis[4,5]. Furthermore, elderly patients present less frequently with the typical symptoms of heartburn, acid regurgitation, and abdominal or chest pain, which are quite different from those of young subjects[6,7]. Several previous studies assessed clinical symptoms and quality of life of GERD patients using the GERD impact scale[8], Chinese GERD questionnaire (GERDQ)[9], and the Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire[10,11]. However, to date, no studies have been conducted to compare the quality of life of young and old patients with GERD. The aim of this study was to compare the presentation and impact on quality of life of GERD in younger and elderly patients in a Chinese population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data from consecutive patients with GERD in our hospital were collected between January 2009 and November 2009. All patients underwent an open-access transoral upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and those who were diagnosed with erosive esophagitis, or had typical symptoms, were considered for inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) GERD combined with other structural gastrointestinal disorders, such as peptic ulcer disease, esophageal or gastric malignancy; (2) prior gastric surgery; (3) use of chronic antacid medication, such as proton pump inhibitors or H2-receptor antagonists, for more than 2 mo prior to enrollment; and (4) pregnancy.

The enrolled patients were assigned to the younger group if they were under the age of 65 years; patients 65 years and over were assigned to the elderly group. All cases were asked to complete the GERD impact scale, the Chinese GERDQ, and the SF-36 questionnaire (Chinese

version), and results were compared between the two groups. Data from other cases without endoscopic findings of erosive esophagitis or symptoms related with GERD were collected and these subjects served as the control group in our study. All study participants completed the SF-36 questionnaire, a widely used health survey.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD deviation for each of the measured parameters. A P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical comparisons were made using Pearson’s χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test, to compare the effects of gender and endoscopic or clinical reflux esophagitis severity, and the independent Student t test was used to analyze scores of each scale and questionnaire.

RESULTS

Among all enrolled consecutive patients between January and November 2009, there were 111 with GERD and 44 normal cases. Patients’ characteristics and endoscopic reflux esophagitis severity are shown in Table 1. Among the patients with GERD, there were 78 patients (70.3%) in the younger group and 33 cases (29.7%) in the elderly group. A similar duration of symptoms was noted between the younger cases (mean 2.82 years) and the elderly cases (mean 2.50 years). Comparing the gender of each group, there were significantly more female patients (60.3%) in the younger group, and more male patients (72.7%) in the elderly group. The elderly patients had greater endoscopic disease severity than the younger patients, based on the Los Angeles classification.

Table 1.

Characteristics and endoscopic symptoms in younger and elderly cases with gastroesophageal reflux disease

| Variable | Younger group(n = 78, 70.3%) | Elderly group(n = 33, 29.7%) | |||

| n (%) | mean ± SD | n (%) | mean ± SD | P value | |

| Mean age (yr) | 37.73 ± 10.17 | 72.94 ± 9.58 | |||

| Symptom duration (yr) | 2.82 ± 3.92 | 2.50 ± 2.99 | 0.3841 | ||

| Gender | 0.0012 | ||||

| M | 31 (39.7) | 24 (72.7) | |||

| F | 47 (60.3) | 9 (27.3) | |||

| Endoscopic reflux esophagitis severity | |||||

| NERD | 15 (19.2) | 0 | 0.0013 | ||

| L.A. Grade A | 50 (64.1) | 16 (48.5) | |||

| L.A. Grade B | 8 (10.3) | 8 (34.2) | |||

| L.A. Grade C | 5 (6.4) | 6 (18.2) | |||

| L.A. Grade D | 0 | 3 (9.1) | |||

Pearson’s χ2 test,

Independent t test,

Fisher’s exact test. F: Females; M: Males; L.A.: Los Angeles classification; SD: standard derivation; NERD: Non erosive reflux disease.

The presentation of the younger and elderly patients with GERD in our study are summarized in Table 2, which show the results of the GERD impact scale. As shown in Table 2, the young cases had a higher prevalence of typical symptoms than the elderly patients, including burning (48.7% vs 15.2%, P = 0.005), pain in chest (64.3% vs 33.3%, P = 0.001), regurgitation of food (79.5% vs 54.6%, P = 0.058), hoarseness (73.1% vs 39.4%, P = 0.010) and chronic conditions related to heartburn (44.8% vs 33.3%, P = 0.708).

Table 2.

Symptom presentation measured by gastroesophageal reflux disease impact scale in younger and elderly patients

| GERD impact scale | Young group(n = 78, 70.3%) | Elderly group(n = 33, 29.7%) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | P value | |

| Burning | 0.005 | ||

| None of the time | 30 (38.50) | 22 (66.70) | |

| A little of the time | 34 (43.60) | 1 (3.00) | |

| Some of the time | 9 (11.50) | 9 (27.30) | |

| All of the time | 6 (6.40) | 1 (3.00) | |

| Pain in chest | 0.001 | ||

| None of the time | 40 (51.30) | 28 (84.80) | |

| A little of the time | 28 (35.90) | 4 (12.20) | |

| Some of the time | 9 (11.50) | 0 | |

| All of the time | 1 (1.30) | 1 (3.00) | |

| Food coming into mouth | 0.058 | ||

| None of the time | 16 (20.50) | 15 (49.40) | |

| A little of the time | 48 (61.50) | 13 (39.40) | |

| Some of the time | 7 (9.00) | 2 (6.10) | |

| All of the time | 7 (9.00) | 3 (9.10) | |

| Hoarseness | 0.01 | ||

| None of the time | 21 (55.20) | 20 (60.60) | |

| A little of the time | 37 (26.90) | 8 (24.20) | |

| Some of the time | 15 (11.50) | 4 (12.20) | |

| All of the time | 5 (6.40) | 1 (3.00) | |

| Chronic heartburn | 0.708 | ||

| None of the time | 43 (55.20) | 22 (66.70) | |

| A little of the time | 21 (26.90) | 6 (18.10) | |

| Some of the time | 9 (11.50) | 3 (9.10) | |

| All of the time | 5 (6.40) | 2 (6.10) | |

All were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

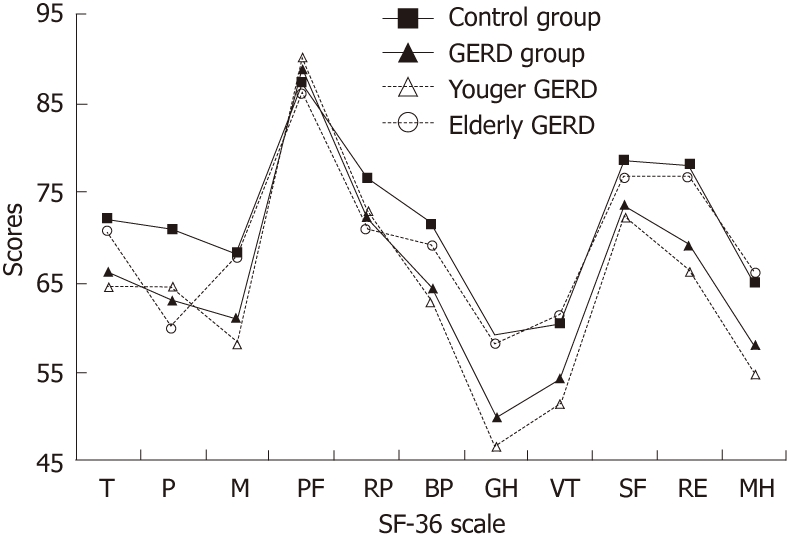

The quality of life results in the two groups measured by the GERD impact scale are shown in Table 3, and the SF-36 questionnaire results are shown in Table 4 and Figure 1. As shown in Table 3, significantly impaired activities of daily living, including sleep disturbance (52.6% vs 18.2%, P = 0.004), feeding and drinking problems (64.1% vs 12.1%, P = 0.001), and impact on social activites (43.6% vs 15.2%, P = 0.005), were noted in the younger patients.

Table 3.

Quality of life measured by quality of life of gastroesophageal reflux disease impact scale in younger and elderly cases

| GERD impact scale | Young group(n = 78, 70.3%) | Elderly group(n = 33, 29.7%) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | P value | |

| Sleep disturbance | 0.004 | ||

| None of the time | 37 (47.40) | 27 (81.80) | |

| A little of the time | 26 (33.30) | 4 (12.10) | |

| Some of the time | 8 (10.30) | 0 | |

| All of the time | 7 (9.00) | 2 (6.10) | |

| Food and drink problems | 0.001 | ||

| None of the time | 28 (35.90) | 29 (78.90) | |

| A little of the time | 31 (39.70) | 3 (9.10) | |

| Some of the time | 6 (7.7) | 0 | |

| All of the time | 13 (16.70) | 1 (3.00) | |

| Social interference | 0.005 | ||

| None of the time | 44 (56.40) | 28 (84.80) | |

| A little of the time | 27 (34.60) | 3 (9.10) | |

| Some of the time | 6 (7.70) | 0 | |

| All of the time | 1 (1.30) | 2 (6.10) | |

All were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Table 4.

Scores of SF36 questionnaire in younger and elderly cases with gastroesophageal reflux disease

| SF-36 | Younger group(n = 78, 70.3%) | Elderly group(n = 33, 29.7%) | |

| mean ± SD | mean ± SD | P value | |

| Total SF 36 score | 64.58 ± 16.84 | 70.73 ± 18.50 | 0.106 |

| Total physical health scores | 64.54 ± 15.96 | 60.03 ± 19.06 | 0.24 |

| Total metal health scores | 54.77 ± 16.18 | 66.18 ± 15.10 | 0.011 |

| Physical functioning | 90.26 ± 15.52 | 88.36 ± 21.00 | 0.342 |

| Role-physical | 72.76 ± 41.91 | 71.21 ± 39.09 | 0.853 |

| Bodily pain | 62.70 ± 18.35 | 69.18 ± 17.99 | 0.089 |

| General perception | 46.47 ± 18.06 | 58.09 ± 19.60 | 0.005 |

| Vitality | 51.22 ± 18.36 | 61.63 ± 19.46 | 0.013 |

| Social functioning | 72.18 ± 18.70 | 76.76 ± 19.73 | 0.263 |

| Role-emotional | 66.24 ± 45.76 | 76.82 ± 36.78 | 0.203 |

| Mental health | 54.77 ± 16.18 | 66.18 ± 15.10 | 0.001 |

All were analyzed by independent t test.

Figure 1.

Scores of SF36 questionnaire among the control cases, and younger and elderly cases with gastroesophageal reflux disease. T: Total SF36 scores; P: Total physical health scores; M: Total metal health scores; RP: Role-physical; RF: Physical functioning; BP: Bodily pain; GH: General perception; VT: Vitality; MH: Mental health; SF: Social functioning; RE: Role-emotional; GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

As shown in Figure 1, comparing the quality of life between cases with and without GERD, patients with GERD had lower scores in all items of the SF-36 questionnaire, except physical functioning. With regard to age, as shown in Table 3, younger patients had higher scores than elderly patients in the items of physical functioning (mean 90.26 vs 86.39, P = 0.342), role-physical limitations (mean 72.76 vs 71.21, P = 0.853), and total physcial health status (mean 64.54 vs 60.03, P = 0.240). In contrast, younger patients had lower scores than elderly patients for the following items: bodily pain (mean 62.70 vs 69.18, P = 0.089), general perception of health (mean 46.47 vs 58.09, P = 0.005), vitality (mean 51.22 vs 61.36, P = 0.013), social functioning (mean 72.18 vs 76.76, P = 0.263), emotional limitations (mean 66.24 vs 76.82, P = 0.203), mental health status (mean 54.77 vs 66.18, P = 0.001), total mental health status (mean 58.15 vs 67.76, P = 0.011), and total health status (mean 64.58 vs 70.73, P = 0.106).

DISCUSSION

GERD is a chronic disease that tends to relapse and develop complications[12], and it is reported to be more severe and to have a higher incidence of severe complications in older vs younger patients[4,13,14]. Moreover, clinical features of GERD in old patients are quite different from those of younger adult subjects, with the elderly presenting less frequently with the typical symptoms of heartburn, acid regurgitation, and pain[15]. Our study findings showed similar results in that most typical symptoms of GERD occurred in the younger patients, but occurred more rarely in the older subjects. The only exception in our study was that acid regurgitation was more frequent in older patients than in young ones, but this difference was non-significant. Hence, the typical esophageal symptoms of GERD, such as heartburn, are unreliable markers when diagnosing this disease in elderly patients[16].

Interestingly, the symptom of hoarseness, which is often considered an extraesophageal symptom of GERD[17], was also more frequently noted in the younger patients. Our results demonstrated that the younger patients with GERD not only had more typical esophageal symptoms but also more extraesophageal symptoms than in the elderly group. Furthermore, a previous study reported roughly one-third of elderly patients may have none of the symptoms usually associated with GERD[6]. It has been suggested that old patients may display symptoms in a different manner compared with young patients.

Patients with GERD may present with a broad range of troublesome symptoms that can damage the quality of their daily lives[18,19]. The negative effects of GERD are dependent on the frequency and severity of symptoms rather than the presence of esophagitis. Studies conducted in Sweden’s general population, which assessed the impact of the severity and frequency of GERD symptoms showed that even symptoms rated as mild are associated with a clinically meaningful reduction in wellbeing[20]. A German study determined that patients with symptoms of GERD had substantially impaired physical and psychosocial aspects of wellbeing compared with the general population, and felt restricted as a result of food and drink problems, disturbed sleep, and impaired vitality and emotional wellbeing[18]. A Chinese study reported that the largest decrements in quality of life scores among all subscales in subjects with GERD symptoms were related to bodily pain and role limitations[21]. Another study found that patients with GERD reported more impairment due to pain but less impairment with regard to physical and role functioning[11]. Our study yielded similar results, namely, that patients with GERD reported impaired quality of life in all dimensions, except physical functioning, compared with quality of life in the normal population.

The quality of life findings revealed slightly lower physical scores in elderly patients with GERD. It is possible that the increased disability or frailty associated with aging may account for the lower physical functioning. In addition, compared with elderly patients, significantly impaired mental health and vitality in the younger GERD patients was found in our study. That is, severity and frequency of symptoms of GERD were associated with impaired quality of life. This finding is consistent with the results of a previous study which showed both severity and perceived discomfort of symptoms were valid markers of the degree of quality of life impairment[22,23].

There were some limitations in our study. Firstly, some personal matters and other co-morbidity of diseases, which tend to influence quality of life, such as psychiatric factors[24], central obesity[25], chronic heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma[26] were not considered. These might have led to scoring bias in the questionnaire. Secondly, overlap of GERD with inflmmatory bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia should be considered. The overlaps were common and might worsen scores of questionnaries in our study according to a previous report[27]. Thirdly, our study design was hospital-based. Further research should include representative samples from the general population to confirm these results.

In conclusion, in the present study, elderly and younger adult patients with GERD in a Chinese population had different characteristics. Elderly GERD patients were predominantly male, rarely presented with typical GERD symptoms and their quality of life was less impaired compared with younger GERD patients.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic disease which has an impact on the everyday lives of affected individuals. The prevalence of the disease increases with age, but elderly patients present less frequently with typical symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation, which are quite different from symptoms of young subjects.

Research frontiers

Several previous studies assessed clinical symptoms and quality of life of GERD patients using the questionnaire. However, to date, no studies have been conducted to compare the quality of life of young and old patients with GERD. The aim of this study was to compare the presentation and impact of quality of life in younger and elderly GERD patients in a Chinese population.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The study found more female patients in the younger group, and more males in the elderly group. The younger cases had more severe and frequent typical symptoms than the elderly patients. Significantly impaired daily activities were noted in the younger patients compared with the elderly group, except for physical functioning.

Applications

The diagnostic features of GERD should be determined in the elderly, since these patients have rare presentations of typical symptoms, and less impaired quality of life compared with younger cases in a Chinese population.

Peer review

It's an interesting and important manuscript in which the vluable index based on patient has been shown.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Bernabe Matias Quesada, MD, Department of Surgery, Hospital Cosme Argerich, Talcahuano 944 9A, Buenos Aires 1013, Argentina

S- Editor Wu X L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Wiklund I. Review of the quality of life and burden of illness in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2004;22:108–114. doi: 10.1159/000080308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mold JW, Reed LE, Davis AB, Allen ML, Decktor DL, Robinson M. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in elderly patients in a primary care setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:965–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furukawa N, Iwakiri R, Koyama T, Okamoto K, Yoshida T, Kashiwagi Y, Ohyama T, Noda T, Sakata H, Fujimoto K. Proportion of reflux esophagitis in 6010 Japanese adults: prospective evaluation by endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:441–444. doi: 10.1007/s005350050293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDougall NI, Johnston BT, Collins JS, McFarland RJ, Love AH. Three to 4.5-year prospective study of prognostic indicators in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:1016–1022. doi: 10.1080/003655298750026688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeitoun P, Salmon L, Bouché O, Jolly D, Thiéfin G. Outcome of erosive/ulcerative reflux oesophagitis in 181 consecutive patients 5 years after diagnosis. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:470–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raiha I, Hietanen E, Sourander L. Symptoms of gastrooesophageal reflux disease in elderly people. Age Ageing. 1991;20:365–370. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilotto A, Di Mario F, Malfertheiner P. Upper gastrointestinal diseases in the elderly. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:801–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones R, Coyne K, Wiklund I. The gastro-oesophageal reflux disease impact scale: a patient management tool for primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1451–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong WM, Lam KF, Lai KC, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lam CL, Wong NY, Xia HH, Huang JQ, Chan AO, et al. A validated symptoms questionnaire (Chinese GERDQ) for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in the Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1407–1413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health related quality of life. Am J Med. 1998;104:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denta J, Brunb J, Fendrickc AM, Fennertyd MB, Janssense J, Kahrilasf PJ, Lauritseng K, Reynoldsh JC, Shawi M, Talley NJ. An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management - the Genval Workshop report. Gut. 1998;44:S1–S16. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.2008.s1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman J, Shohat V, Tsvang E, Arnon R, Safadi R, Wengrower D. Esophagitis is a major cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the elderly. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:906–909. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fass R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease revisited. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2002:31: S1–S10. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(02)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, Novello R, Di Mario F, Valerio G. Long-term clinical outcome of elderly patients with reflux esophagitis: a six-month to three-year follow-up study. Am J Ther. 2002;9:295–300. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson DA, Fennerty MB. Heartburn severity underestimates erosive esophagitis severity in elderly patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:660–664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahrilas PJ. Clinical practice. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1700–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulig M, Leodolter A, Vieth M, Schulte E, Jaspersen D, Labenz J, Lind T, Meyer-Sabellek W, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M, et al. Quality of life in relation to symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-- an analysis based on the ProGERD initiative. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:767–776. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley NJ. Review article: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease -- how wide is its span? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 5:27–37; discussion 38-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiklund I, Carlsson J, Vakil N. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and well-being in a random sample of the general population of a Swedish community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M, Xiong L, Chen H, Xu A, He L, Hu P. Prevalence, risk factors and impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a population-based study in South China. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:759–767. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dekel R, Green C, Quan S, Stephen G, Fass R. The relationship between severity and frequency of symptoms and quality of sleep (QOS) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Gastroenterol. 2003;124:A414. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Junghard O, Talley NJ, Agreus L. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms and health-related quality of life in the adult general population--the Kalixanda study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1725–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansson C, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Johnsen R, Hveem K. Stressful psychosocial factors and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a population-based study in Norway. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:21–29. doi: 10.3109/00365520903401967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nandurkar S, Locke GR, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, Cameron AJ, Talley NJ. Relationship between body mass index, diet, exercise and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in a community. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:497–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai MC, Lin HL, Lin CC, Lin HC, Chen YH, Pfeiffer S, Lin LH. Increased risk of concurrent asthma among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a nationwide population-based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1169–1173. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32833fb68c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaji M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Kohata Y, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe K, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Arakawa T. Prevalence of overlaps between GERD, FD and IBS and impact on health-related quality of life. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1151–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]