Abstract

The Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program's goal is to foster the next generation of clinical investigators and to help build international health research partnerships between American and international investigators and institutions. Through June 2012, 61 sites in 27 countries have hosted 436 Scholars (American students or junior trainees from the host countries) and/or 122 Fellows (American and host country postdoctoral fellows) for year-long experiences in global health research. Initially, the program was oriented toward infectious diseases, but recently emphasis on chronic disease research has increased. At least 521 manuscripts have been published, many in high-impact journals. Projects have included clinical trials, observational studies, translational research, clinical-laboratory interface initiatives, and behavioral research. Strengths of the program include training opportunities for American and developing country scientists in well-established international clinical research settings, and mentorship from experienced global health experts.

Introduction

In the past decade, a groundswell of interest in experiences and training opportunities in global health has occurred among students of medical, public health, and other health professions in the United States. This trend is shown by substantial increases in numbers of medical students seeking international rotations;1 the creation of partnerships between U.S. health care institutions and teaching hospitals in developing countries;2 and increased numbers of training experiences in research, clinical care, and public health in resource-limited settings.3–6

The optimal venue in which to provide global health research training for U.S. and international trainees is in situ, embedded in public health, treatment, and research programs in low-income and middle-income countries that are designed to provide mutual benefit to both sending and hosting institutions.7 Recognizing this fact, in 2003 the Fogarty International Center (FIC) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), with additional support from other NIH institutes and centers and the Ellison Medical Foundation, established a program to provide training opportunities for professional and doctoral students in global clinical research. In 2008, the program was expanded in size and scope, with postdoctoral clinical and research fellows included. We provide a program description and report early outcomes.

Program description and trainee selection

Scholars Program.

The Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars Program (FICRS, www.fogartyscholars.org) was initiated in 2003 with the goal of fostering the next generation of clinical investigators and to help build international health research partnerships between American and international investigators and institutions. It is a one-year mentored training experience that provides opportunities for U.S. graduate students and matched international trainees in the health professions and medical sciences to participate in clinical research, gaining hands-on experience at vetted research centers funded by the U.S. NIH in low-income and middle-income countries in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and eastern Europe (Table 1).

Table 1.

Research training sites, countries, and affiliated U.S. institutions*

| Country (city) | Performance site | U.S. or other partner institution | Scholar site | Fellow site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina (Buenos Aires) | Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy (IECS) | Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine | x | |

| Argentina (Buenos Aires) | Fundacion Infant | Vanderbilt University Medical Center | x | |

| Bangladesh (Dhaka) | International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research | Massachusetts General Hospital | x | x |

| Bangladesh (Dhaka) | International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research | None | x | x |

| Botswana (Gaborone) | Botswana-Harvard School of Public Health AIDS Initiative Partnership (BHP) | Harvard University, Harvard School of Public Health | x | x |

| Botswana (Gaborone) | Botswana–University of Pennsylvania Partnership | University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine | x | |

| Brazil (Fortaleza) | Federal University of Ceara, Institute of Biomedicine; Clinical Research Unit | University of Virginia, Center for Global Health | x | |

| Brazil (Rio de Janeiro) | Fundacao Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) | None | x | |

| Brazil (Salvador) | Federal University of Bahia | Weill Cornell Medical College, Division of International Medicine and Infectious Diseases | x | x |

| Chile (Santiago) | Universidad del Desarrollo | University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center | x | |

| China (Beijing) | National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, China CDC | Vanderbilt University Institute for Global Health | x | x |

| China (Beijing) | The George Institute for International Health | None | x | |

| China (Beijing) | National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, China CDC | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Gillings School of Global Public Health | x | x |

| China (Nanjing) | National Center for STD and Leprosy Control, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College | UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases | x | x |

| China (Nanjing) | National Center on AIDS/STD Control and Prevention | University of California, San Francisco | x | |

| China (Shanghai) | Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention | Vanderbilt University, Epidemiology Center | x | x |

| Costa Rica (San José) and Mexico (Chiapas) | Comprehensive Center for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases in Mesoamerica and the Dominican Republic | RAND Corporation | x | |

| Guatemala (Guatemala City) | Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP) | RAND Corporation | x | |

| Haiti (Port Au Prince) | Haitian Group for the Study of Kaposi's Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections (GHESKIO) | Weill Cornell Medical College, Division of International Medicine and Infectious Diseases | x | x |

| Honduras (Santa Rosa de Copan) | Hospital Regional del Occidente | None | x | |

| India (Chennai) | YR Gaitonde Center for AIDS Research and Education (YRG CARE) | The Miriam Hospital; Brown University | x | |

| India (Mumbai) | Partners for Urban Knowledge, Action, and Research (PUKAR) | None | x | |

| India (New Delhi) | All India Institute of Medical Sciences | None | x | |

| India (New Delhi) | Public Health Foundation of India | Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University | x | x |

| India (Vellore) | Christian Medical College | Tufts University School of Medicine | x | x |

| India (Bangalore) | St. John's Medical College and Research Institute | None | x | |

| Jamaica (Mona) | University of the West Indies, Mona Campus | None | x | |

| Kenya (Eldoret) | Moi University School of Medicine | The Miriam Hospital; Brown University | x | x |

| Kenya (Nairobi) | University of Nairobi | University of Washington, International AIDS Research and Training Program (IARTP) | x | x |

| Kenya (Nairobi) | Kenya Medical Research Institute | University of Washington, International AIDS Research and Training Program (IARTP), Tufts University Medical Center | x | |

| Malawi (Lilongwe) | UNC Project | University of North Carolina Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases | x | x |

| Mali (Bamako) | University of Bamako/Mali Service Center, Malaria Research and Training Center | University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore | x | x |

| Mexico (Baja) | Universidad Autonoma de Baja California, Instituto Mexicano del Sueguro Social | Scripps Health | x | |

| Mexico (Juarez) | Mexico-Juarez–UTEP | University of Texas at El Paso | x | |

| Mozambique (Maputo) | Faculty of Medicine, University of Eduardo Mondlane; Friends in Global Health | Vanderbilt University Institute for Global Health | x | |

| Nigeria (Ibadan) | University of Ibadan, University College Hospital | University of California, Los Angeles | x | |

| Nigeria (Ilorin) | Sobi Specialist Hospital (Ilorin, Kwara) | Vanderbilt University Institute for Global Health | x | |

| Peru (Lima) | Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Investigación Medica en Salud (INMENSA) | University of Washington IARTP | x | x |

| Peru (Lima) | Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, A.B. PRISMA | Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of International Health | x | x |

| Peru (Lima) | Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia | The University of Texas Medical Branch | x | |

| Rwanda (Kigali) and Zambia (Lusaka) | Rwanda–Zambia HIV Research Group | Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health | x | |

| Rwanda (Kigali) | Rwinkwavu Hospital | Brigham and Women's Hospital | x | |

| South Africa (Cape Town) | Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town | None | x | |

| South Africa (Cape Town) | Desmund Tutu HIV Center and Institute of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape Town | None | x | |

| South Africa (Cape Town) | Stellenbosch University | None | x | |

| South Africa (Durban) | Center for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) | Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University | x | x |

| South Africa (Durban) | Nelson Mandela School of Medicine, University of Kwazulu-Natal | None | x | |

| South Africa (Johannesburg) | Reproductive Health and HIV Research Unit, University of Witwatersrand | None | x | |

| Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) | Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) | Harvard School of Public Health | x | x |

| Tanzania (Moshi) | Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC) | Duke University, Hubert Yeargan Center for Global Health | x | x |

| Thailand (Bangkok) | Chulalongkorn University | None | x | |

| Thailand (Chiang Mai) | Research Institute for Health Educations Sciences, Chiang Mai University | Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health | x | x |

| Thailand (Mae Sot) | Shoklo Malaria Research Unit | None | x | |

| Tunisia (Sousse) | University Hospital Farhat Hached | Duluth Medical Research Institute, University of Minnesota Medical School | x | |

| Uganda (Kampala) | Joint Clinical Research Center, Makerere University | Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), AIDS International Training and Research Program | x | x |

| Uganda (Kampala) | Mulago Hospital Complex, Makerere University, Infectious Diseases Institute | None | x | x |

| Uganda (Mbara) | Mbara University of Science and Technology | None | x | |

| Vietnam (Ho Chi Minh City) | Oxford University, Clinical Research Unit | Oxford University | x | |

| Vietnam (Hanoi) | Vietnam National University | None | x | |

| Zambia (Lusaka) | Center for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ) | University of Alabama at Birmingham, Division of International Women's Health | x | x |

| Zambia (Lusaka) | University of Zambia School of Medicine | Vanderbilt University, Institute for Global Health | x |

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; STD = sexually transmitted disease; Div. = Division; CDC = Center for Disease Control; UTEP = University of Texas at El Paso; HIV = human immunodeficiency syndrome.

The U.S. Scholars are professional or graduate students in doctoral programs in all disciplines of the health sciences who express serious interest in potential careers in global health research. They are selected through a competitive application and interview process. Typical cohorts comprise doctoral candidates in allopathic or osteopathic medicine, public health (e.g., epidemiology, international health, and behavioral sciences), veterinary medicine, dentistry, nursing, and pharmacy. All U.S. Scholars are matched or twinned with foreign national Scholars chosen by the international research sites through individually administered selection processes. The non-U.S. Scholars need not be students, but can be junior post-graduate trainees. The U.S. and international Scholars may collaborate on common research projects, or they may engage in different projects. International Scholars serve as resources for the U.S. Scholars in research, cultural understanding, and, typically, friendship. In turn, U.S. Scholars may bring specific clinical or research skills that are shared in-country with their counterparts. By completing research training entirely in the international sites, the program provides a mentored opportunity for both training and capacity building in the foreign research sites.

Scholar candidates from the United States apply online annually, and finalists selected by an external review committee are interviewed individually by representatives of the international training sites at a meeting held on the NIH campus. Applicants and site representatives then submit rank order preference lists that are used to match applicants to sites.

Fellows Program.

The program was expanded in 2008 to include postdoctoral trainees. The Fogarty International Clinical Research Fellows (FICRF) Program is intended to fill a critical gap in global health research training between the completion of a professional or academic doctoral program and readiness to apply for more advanced career development awards or research grants. Eligible applicants are U.S. and international medical residents and Fellows, and postdoctoral scientists enrolled in health-related training programs.

Fellow applicants apply online annually, including a description of a research project. Finalists selected by an external review committee are subsequently interviewed via telephone by members of a separate committee. Fellowships are awarded on the basis of evaluations of the applications and interviews, and the priorities of the available funding sources for the given year. Together, the Scholars and Fellows programs are called the Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program (FICRS-F).

Site selection.

The initial 14 training sites were selected from supplemental award proposals received from FIC training grant recipients. Eligibility was restricted to sites with NIH-funded research, post-graduate educational programs, on-site full-time mentors, and consideration of other factors such as housing, safety, and language requirements. Subsequent sites were added to provide greater geographic diversity and breadth of research activities. In 2008, all the sites were re-competed; 25 sites were selected for the Scholars and the Fellows programs and an additional 24 sites were approved for the Fellows program alone. As Fellow applicants have applied to work in new sites, additional Fellows sites have been added.

Training experience.

The training experience for all U.S. and international Scholars and Fellows begins with a two-week July orientation and training session held on the NIH campus. The orientation reviews key principles of clinical and translational research, the histories and contributions of key organizations involved in global health, particularly the NIH, issues in cultural competency and integration, and talks by global health scientists and leaders from NIH and around the world. Typically, Scholars and Fellows visit the U.S. institutions affiliated with their respective training sites for a brief orientation to their specific programs (Table 1), and then depart for 10–11 months at the training sites. Several U.S. Scholars and Fellows have brokered additional resources to continue their overseas training for an extended stay abroad to complete ongoing research projects.

The FICRS-F Program defines clinical research as research directly related to human health and designed to clarify a problem in human physiology, pathophysiology or disease, human behavior, public health, or disease etiology. Typical disciplines engaged during training include epidemiology, behavioral science, physiology, molecular biology, immunology, information technology, behavioral sciences, implementation science, health services research, development of new technologies, therapeutic interventions, and clinical trials. Work related to prevention of disease is encouraged.

Funding and administration.

To provide programmatic support to the FICRS-F Program, the FICRS-F Support Center at Vanderbilt was established through an R24 research support grant by FIC in 2007.8 The Support Center provides overall program management, information dissemination and applicant selection, communication, program coordination and logistics, program monitoring and evaluation, organization of educational programs and conferences, and tracking and maintenance of relationships with program alumni. Assessment of mentorship and the quality of the training experience, as well as the productivity of the trainee, are vital components of the Support Center's responsibilities. Outreach to numerous health-science fields is also conducted by the original partner in the Support Center, the Association of American Medical Colleges, with its focus on medical students and clinical residents and Fellows, complemented by the Association of Schools of Public Health, which focuses on all other health science disciplines.

The cost of a Scholar pair or a single Fellow is approximately $100,000, although costs vary significantly depending on the country of training and type of trainee. Approximately 70–90% of the funds support the trainees' direct costs, such as stipends, insurance, training funds, travel, and orientation. The remainder supports infrastructure and capacity-building at the host international sites, and program administration costs. Significant economies of scale were achieved by having a central support center that required only approximately 7% of total costs. Several NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs) partner with the FIC by contributing support to the program to increase trainee numbers and to focus some Scholar and Fellow placements on research activities related to the participating ICs' areas of scientific interest. As more ICs have shown interest in the FICRS-F Program (Table 2), research diversity for trainees has expanded to encompass not only infectious diseases, but oncology, chronic disease, ophthalmology, nursing, and veterinary medicine. For example, 11 FICRS-F sites are also Collaborating Centers of Excellence in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/United Health Chronic Disease Initiative in low- and middle-income countries (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/globalhealth/). Participation as FICRS-F sites was a requirement for eligibility for the Centers of Excellence network in an effort to bridge the training and research mission of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–supported sites.

Table 2.

Participating NIH institutes and centers*

| NIH institute or center | Year of initial FICRS-F participation |

|---|---|

| John E. Fogarty International Center (FIC) | 2003 |

| Office of the Director (OD) | |

| Office of AIDS Research (OAR) | 2007 |

| Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) | 2008 |

| Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) | 2009 |

| National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD)† | 2004 |

| National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) | 2005 |

| National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) | 2009 |

| National Cancer Institute (NCI) | 2007 |

| Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) | 2007 |

| National Eye Institute (NEI) | 2008 |

| National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) | 2007 |

| National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) | 2005 |

| National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) | 2008 |

| National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) | 2007 |

| National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) | 2007 |

| National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) | 2007 |

NIH = National Institutes of Health; FICRS-F = Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program.

In 2010, the NCMHD was re-designated as the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD).

Tracking and outcome evaluation.

Scholars' and Fellows' career trajectories are followed-up for 20 years after completion of their FICRS-F year, as required by the FIC/NIH, to estimate the program's impact on the global health research workforce. Mid-year and end-of-year assessments of the training experience are administered by the Support Center though the Vanderbilt University online survey and database tool, REDCap™.8 Survey topics include quality of the training experience and evolving interest in global health and research.

In this follow-up, trainees submit updated curricula vitae every year to the Support Center, including a report of presentations, publications, and other activities. Field training site principal investigators help ensure completeness of documentation. Captured in the REDCap™ database, productivity indices are reported in a Research Accomplishments book maintained by the Support Center and in CareerTrac, an online reporting system developed by the Fogarty International Center. Publication outcomes reported here are based on records as of July 2011.

Results

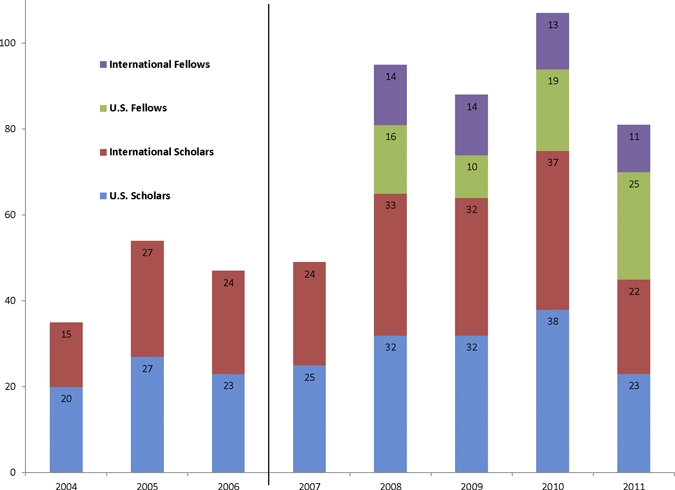

Through June 2012, eight cohorts of Scholars have engaged in mentored international clinical research, including 221 U.S. Scholars and 215 international Scholars selected by the foreign sites (Figure 1 and Table 3). The four cohorts of Fellows have totaled 70 U.S. Fellows and 52 international Fellows, bringing the total to 558 trainees to date, working in 61 sites in 27 countries (Table 4). All but three of 391 (0.8%) Scholars in the completed cohorts to date (2004–2011) have completed the program, and all but one (1.1%) of 87 Fellows in the finished cohorts (2008–2011) have completed the program.

Figure 1.

Numbers of U.S. and international scholars and fellows by year deployed, 2004–2011. Vertical line indicates the year in which the Support Center grant was awarded to the Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health.

Table 3.

Demographics of scholars and fellows*

| Characteristic | U.S. scholars | International scholars | U.S. fellows | International fellows |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 221 | 215 | 70 | 52 |

| Female, % | 56.4 | 46.5 | 58.6 | 60 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 27 (26–29) | 32 (29–35) | 32 (31–35) | 34 (32–38) |

| Current discipline, % | ||||

| Biomedical sciences | 0.0 | 15.0 | 5.7 | 3.9 |

| Dentistry | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Medicine | 80.0 | 53.3 | 71.4 | 64.7 |

| Medicine and public health | 2.7 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 13.7 |

| Mental and behavioral health | 0.5 | 1.4 | 7.1 | 2.0 |

| Missing or other | 0.9 | 9.8 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Nursing | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nutrition | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ophthalmology | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 0.0 |

| Osteopathic medicine | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Pharmaceutical sciences | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| Public health | 6.8 | 6.1 | 2.9 | 7.8 |

| Veterinary medicine | 3.2 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

IQR = interquartile range.

Table 4.

Scholars and fellows by country

| Location | Center | Scholars | Fellows | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Botswana | 18 | 2 | 20 |

| Kenya* | 29 | 21 | 50 | |

| Malawi | 6 | 9 | 15 | |

| Mali | 14 | 0 | 14 | |

| Mozambique | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Nigeria | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Rwanda | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Rwanda/Zambia | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| South Africa* | 27 | 19 | 45 | |

| Tanzania* | 26 | 4 | 30 | |

| Uganda* | 25 | 1 | 26 | |

| Zambia | 25 | 9 | 32 | |

| 11 countries | 244 | |||

| Asia, Eastern Europe | Bangladesh* | 22 | 0 | 22 |

| China* | 39 | 7 | 46 | |

| India* | 43 | 7 | 50 | |

| Russia | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| Thailand | 24 | 3 | 28 | |

| Vietnam | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 6 countries | 151 | |||

| Central and South America, Caribbean | Argentina | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Brazil | 29 | 2 | 30 | |

| Haiti | 17 | 1 | 18 | |

| Honduras | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Jamaica | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mexico | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Peru* | 85 | 14 | 98 | |

| 7 countries | 163 | |||

Countries with more than one site and more than one affiliated U.S. institution.

Basic demographics of the trainees are shown in Table 3. Except for international Scholars, most trainees have been women. The U.S. Scholars have tended to be younger than their international twins, who had typically completed all formal training before being selected for the Program. Most cohorts have been physicians; public health comprised the second most common background.

Scholars and Fellows have pursued research in a wide variety of topic areas (Table 5). The preponderance of research is related to infectious diseases, especially human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), including disease transmission, diagnostic methods, treatment, and detection and management of complications. However, projects focusing on chronic conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, trauma, and mental illness are growing with support from partnering NIH ICs (Table 2).

Table 5.

Trainee research project topics

| Research focus | No. |

|---|---|

| Behavioral studies, stigma | 40 |

| Bioassays, diagnostics, drug resistance | 8 |

| Cancer | 18 |

| Cardiovascular disease, diabetes | 8 |

| Child or infant health, adolescent health | 30 |

| Chronic disease, aging | 8 |

| Climate | 4 |

| Dental/oral health | 3 |

| Diarrheal and gastrointestinal diseases | 15 |

| Economics, education, trauma and injury | 3 |

| Eye or ear disease | 5 |

| Genetics | 9 |

| HIV/AIDS, opportunistic infections | 91 |

| Infectious diseases, disease transmission | 28 |

| Maternal/women's health, pregnancy, contraceptives | 20 |

| Mental health, neurological disorders, stroke | 12 |

| Nutrition | 12 |

| Parasitic disease, including malaria | 23 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 18 |

| Substance abuse, tobacco-related diseases | 10 |

| Tuberculosis | 24 |

| Vaccines, viral diseases including hepatitis | 10 |

| Zoonoses, including leptospirosis | 4 |

HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Many trainees work on more than project during their training year. This list reflects all projects with Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program trainee participation. Topics that covered two topics, such as oral health manifestations of HIV, are listed under both topics.

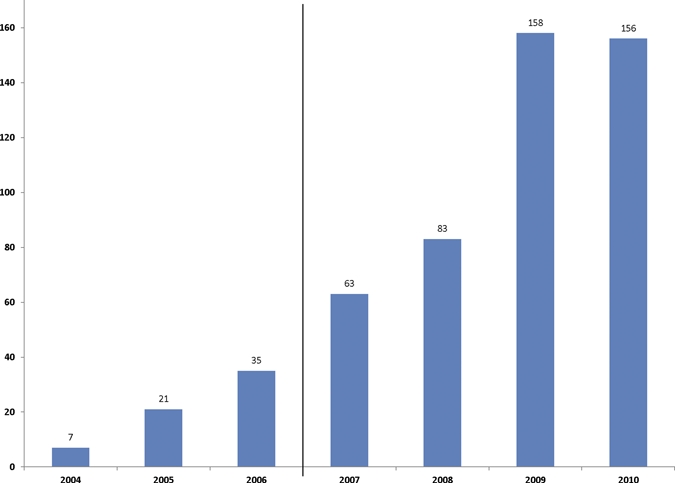

At least 521 manuscripts have been published by FICRS-F alumni from the 2003–2010 cohorts from their work during and after FICRS-F support, including many in relatively high-impact journals (Table 6). A FICRS-F trainee appears as first author in 223 publications, and at least 105 publications have more than one trainee as a coauthor. Among these are publications that influenced international guidelines for co-treatment of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis9; documented social determinants of the resurgence of syphilis in China10 and proposed worldwide adoption of rapid syphilis testing11; modeled a nationwide analysis of the utility of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA testing as a primary screen for cervical cancer in China12; and outlined opportunities for research training in cardiology in the developing world.13 Fellows are more advanced in their careers than are Scholars and often publish several papers while still in their year of FICRS-F support (Figure 2).

Table 6.

Number of Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program alumni publications in high-impact journals as of December 2010

| Journal name | No. | Impact factor* |

|---|---|---|

| New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, Journal of the American Medical Association, Science | 12 | 30–47 |

| Journal of Clinical Oncology, Lancet Infectious Diseases, Circulation, Lancet Oncology, British Medical Journal, PLoS Medicine | 15 | 13–18 |

| American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Annual Review of Medicine, Archives of Internal Medicine, PLoS Genetics, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA, PLoS Pathogens | 9 | 9–11 |

| Clinical Infectious Diseases | 20 | 8.2 |

| Neurology, Emerging Infectious Diseases, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | 6 | 6.3–8.2 |

| Journal of Infectious Diseases | 12 | 5.9 |

| Journal of Immunology, American Journal of Epidemiology, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, Journal of Virology, Mayo Clinic Proceedings | 10 | 5.0–5.7 |

| AIDS | 12 | 4.9 |

| Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Atherosclerosis, Antiviral Therapy | 12 | 4.3–4.8 |

| PLoS One | 13 | 4.4 |

| Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes | 17 | 4.2 |

| Infection and Immunity | 10 | 4.2 |

| Journal of Clinical Microbiology, Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, Gynecologic Oncology, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, Vaccine, Journal of Vascular Surgery | 15 | 3.5–4.2 |

| Cancer Causes and Control, Preventive Medicine, Menopause (New York, NY), Virology, Malaria Journal, Obesity Surgery, Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal | 16 | 2.9–3.2 |

| American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, World Journal of Surgery, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, BMC Infectious Diseases, International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, Sexually Transmitted Infections, International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica | 63 | 2.2–2.8 |

Impact factors from the Journal Citations database of the Information Sciences Institute Web of Knowledge (www.isiknowledge.com/).

Figure 2.

Alumni publications by year, 2004–2010. Vertical line indicates the year in which the Support Center grant was awarded to the Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health. Includes only trainees who have completed a Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program–supported year.

We have further catalogued 461 scientific posters, 147 oral conference presentations, 35 book chapters, 69 post-training funding awards (27 from NIH), and 122 additional honors or awards; alumni have mentored at least 36 students after their research years. The program is young enough that many of even the earliest Scholar alumni have only recently completed their final training, and many are still in postdoctoral clinical or research training fellowships. Thus, the final career paths of the alumni are largely yet to be determined. Nonetheless, career paths of FICRS-F alumni include many positions of note. One alumna is a University of KwaZulu Natal faculty member and Head of Treatment Research Program at a large HIV/AIDS clinic at the Center for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa. Another alumna is Assistant Professor of Medicine (Infectious Diseases) at the University of North Carolina, spending six months each year researching syphilis onsite in Guangzhou, China. One alumna is Instructor in Medicine (Infectious Diseases) at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, spending nine months each year in research on HIV and cancer in Botswana. Some U.S. alumni now conduct research full-time overseas, and nearly all international alumni continue to work in their home countries.

An Alumni Symposium held near the NIH campus in September 2010 brought 138 U.S. and foreign FICRS-F alumni to present their scientific output, showcase their career trajectories, and interact with mentors, program faculty, and NIH officials, including the NIH director and several IC directors. Nine alumni of the Doris Duke Clinical Research Fellowship for medical students (http://www.ddcf.org/mrp-crf) who had conducted their fellowships in developing countries also participated. Trainees cited the huge impact the program has had on their career development. The Alumni Symposium also renewed and strengthened the international interdisciplinary network among FICRS-F alumni, site mentors, and NIH staff.

Discussion

The Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program was founded to train and inspire doctoral students in the health professions and medical scientists for careers in global health research. Now expanded to include postdoctoral Fellows, the FICRS-F program has made a substantial contribution to the numbers of young U.S. and international scientists and health professionals trained specifically to conduct research in resource-limited settings. By placing trainees in sites that already have substantial biomedical and biobehavioral research underway, dedicated national staff closely linked to U.S.-based scientists and academic institutions help mentor the U.S. and local Scholars and Fellows within world-class research teams. Scholars and Fellows participate in top-quality ongoing research projects and, with the approval of the site directors, may initiate ancillary projects of their own design or add components to the ongoing research that could not be done without their input.

The program periodically encounters challenging issues. Some relate to the level and availability of on-site mentorship. Obtaining Institutional Review Board and ethical review certifications and approvals across multiple institutions and countries can cause delays that, although unavoidable, can threaten the relatively short training period. Safety can be tenuous in environments that have inherent risks from motor vehicle accidents, violence, or tropical diseases. Trainees have experienced all of these, most tragically in the case of a U.S. scholar in Uganda who died after a motor vehicle accident in 2010, the only fatality in the program's history. Comprehensive safety counseling is part of the orientation at the NIH, but risks are extant nonetheless. Results of end-of-year trainee evaluations and first-hand experiences with such challenges are examined on an ongoing basis to strengthen FICRS-F programming. The Support Center maintains basic standard procedures that are available, and plans to share obstacles and lessons learned in future publications.

As the FICRS-F Program matures, the Support Center at Vanderbilt is engaged in monitoring and documenting career paths of FICRS-F alumni. A significant limitation with regard to documenting the impact of the FICRS-F Program is the lack of an appropriate comparison group, making it difficult to prove that it was participation in FICRS-F and not a prior passion or other factors that were responsible for ultimate career paths in global health research.

The lifeblood of the FICRS-F Program is clearly the consistent and passionate support of the FIC and its co-sponsoring NIH ICs and engaged U.S. and international mentors. The total size of the trainee cohort depends heavily on the degree of IC co-funding. A minority of the 27 NIH ICs participate currently (Table 2), and substantially greater opportunity could be opened, and impact anticipated, if more ICs participated.

In summary, the FICRS-F Program is a groundbreaking effort to nurture a new generation of researchers focused on chronic and infectious diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Since it was established by the Fogarty International Center in 2003, U.S. and international alumni of the FICRS-F Program are scientists and health professionals with substantial exposure to field research. These individuals are primed for future leadership positions in research, health care, governmental and nongovernmental organizations, and academic institutions in the United States and in low-income and middle-income countries worldwide. The long-term impact of the program on the global health research workforce will evolve and will be documented through tracking of outputs and impacts of FICRS-F alumni. The investment of NIH vision and resources into this program will yield results for decades to come, building U.S. and international research human power and improving the health of persons in resource-limited nations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Roger Glass, Kenneth Bridbord, and Myat Htoo Razak (Fogarty International Center), the FICRS-F Site Principal Investigators and mentors, and participating NIH institute and center directors and staff for their support.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director, Fogarty International Center, Office of AIDS Research, National Cancer Institute, National Eye Institute, National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute On Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Health, through the Fogarty International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt–Association of American Medical Colleges (R24 TW007988). Further support in 2010 and 2011 was received from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds (http://recovery.nih.gov/).

Disclosure: The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Authors' addresses: Douglas C. Heimburger, Catherine Lem Carothers, Tokesha L. Warner, and Sten H. Vermund, Institute for Global Health, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, E-mails: douglas.heimburger@vanderbilt.edu, catherine.lem@vanderbilt.edu, tokesha.warner@vanderbilt.edu, and sten.vermund@vanderbilt.edu. Pierce Gardner, Office of the Dean, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, E-mail: gardnep@mail.nih.gov. Aron Primack, Silver Spring, MD, E-mail: primack@rcn.com.

References

- 1.Panosian C, Coates TJ. The new medical “missionaries”: grooming the next generation of global health workers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1771–1773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riviello R, Ozgediz D, Hsia RY, Azzie G, Newton M, Tarpley J. Role of collaborative academic partnerships in surgical training, education, and provision. World J Surg. 2010;34:459–465. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0360-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah SK, Nodell B, Montano SM, Behrens C, Zunt JR. Clinical research and global health: mentoring the next generation of health care students. Glob Public Health. 2010;6:1–13. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.494248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McElmurry BJ, Misner SJ, Buseh AG. Minority international research training program: global collaboration in nursing research. J Prof Nurs. 2003;19:22–31. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2003.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman DO, Gotuzzo E, Seas C, Legua P, Plier DA, Vermund SH, Casebeer LL. Educational programs to enhance medical expertise in tropical diseases: the Gorgas Course experience 1996–2001. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:526–532. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84:320–325. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crump JA, Sugarman J. Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:1178–1182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermund SH, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Khedkar S, Jia Y, Etherington C, Vergara A. Building global health through a center-without-walls: the Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health. Acad Med. 2008;83:154–164. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318160b76c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, Padayatchi N, Baxter C, Gray A, Gengiah T, Nair G, Bamber S, Singh A, Khan M, Pienaar J, El-Sadr W, Friedland G, Abdool Karim Q. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker JD, Chen X-S, Peeling RW. Syphilis and social upheaval in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1658–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker JD, Bu J, Brown LB, Yin Y-P, Chen X-S, Cohen MS. Accelerating worldwide syphilis screening through rapid testing: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:381–386. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao F-H, Lin MJ, Chen F, Hu S-Y, Zhang R, Belinson JL, Sellors JW, Franceschi S, Qiao Y-L, Castle PE. Performance of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA testing as a primary screen for cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from 17 population-based studies from China. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70256-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloomfield GS, Huffman MD. Global chronic disease research training for fellows: perspectives, challenges, and opportunities. Circulation. 2010;121:1365–1370. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.923144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]