Abstract

Sulfonation is prized for its ability to impart water-solubility to hydrophobic molecules such as dyes. This modification is usually performed as a final step, since sulfonated molecules are poorly soluble in most organic solvents, which complicates their synthesis and purification. This work compares the intrinsic lability of different sulfonate esters, identifying new sulfonate protecting groups and mild, selective cleavage conditions.

There are many choices of protecting groups for alcohols, phenols, carbonyls, carboxylates, thiols, and amines, but few examples of protecting groups for sulfonic acids.1 Protection of sulfonates as simple esters is problematic because sulfonate esters are potent electrophiles. To overcome this issue, a number of sterically-hindered protecting groups for sulfonic acids have been proposed and utilized for the synthesis of sulfonated molecules. Secondary isopropyl (iPr) sulfonates react more slowly with nucleophiles, but are poorly stable to acidic conditions, chromatography, and prolonged storage.2,3,4 Isobutyl (iBu) sulfonates are more stable to acidic conditions and can be stored, but exhibit increased sensitivity to nucleophilic cleavage.2,5 Neopentyl (Neo) sulfonates are highly hindered and thus strongly resistant to nucleophilic displacement, but are difficult to remove.6 Trichloroethyl (TCE) sulfonates are stable to non-basic nucleophiles, but react with basic nucleophiles.7

Triggered “safety-catch” sulfonate protecting groups have been described that utilize the inherent stability of neopentyl sulfonates, combined with an intramolecular trigger that allows selective removal.6,8 Roberts et al.6 pioneered this approach, creating a Boc-containing neopentyl protecting group dubbed “Neo N-B”; removal of the Boc group with TFA followed by subsequent neutralization of the unmasked amine allows cyclative cleavage of the sulfonate. However, these triggered sulfonate protecting groups have not found wide use, in part due to the need for their multi-step synthesis, and inherent high cost. Ideally, protecting groups should be inexpensive, stable to a wide variety of conditions, and selectively cleaved to liberate the free sulfonate without requiring further purification steps.

There has been little direct comparison of the intrinsic stability properties of sulfonate esters formed from commercially-available alcohols to reaction conditions commonly encountered in organic synthesis. Since my lab routinely synthesizes sulfonated molecules, we are interested in expanding the range of available sulfonate protecting groups and in establishing the chemical stability of each sulfonate ester.

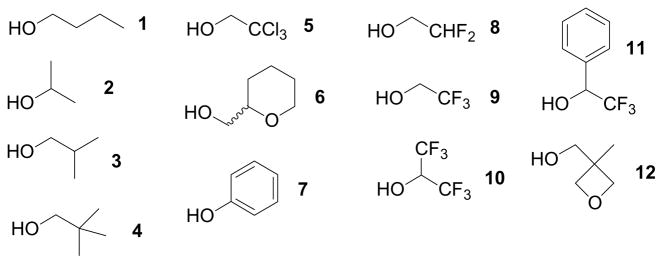

Beta-fluorinated electrophiles are particularly resistant to nucleophilic substitution due to electronic deactivation of reactivity.9 For example, trifluoroethyl iodide and trifluoroethyl sulfonates are highly recalcitrant to nucleophilic substitution; displacement requires high temperatures and extended reaction times.10 Potential sulfonate protecting groups thus include esters of difluoroethanol (DFE), hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), trifluoroethanol (TFE), and alpha-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl alcohol (TFMB).11 Other candidate sulfonate protecting groups include phenyl (Ph; because it is sp2-hybridized), tetrahydropyran-2-methyl (THPM; reported to be more stable to nucleophiles than iBu12), and 3-methyl-3-oxetane-methanol, which is nominally a neopentyl alcohol (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Commercially available alcohols as potential sulfonate protecting groups.

Dansyl sulfonate esters of twelve candidate alcohols were synthesized to screen the stability of each protecting group to different reaction conditions. Dansyl esters fluoresce yellow-green, while the liberated free dansyl sulfonate fluoresces blue. This allows the rapid detection of cleavage by TLC and by visual inspection of the reaction vial using a hand-held UV lamp. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stability profiles of dansylates formed from commercially-available alcohols.

| Dansylate | NaIa | Piperidineb | NaN3c | Fe(0)d | NaOHe | HBrf | BBr3g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nBu (1) | − | − | + | o | − | o | |

| iPr (2) | − | − | o | − | − | − | |

| iBu (3) | − | − | + | o | − | − | |

| Neo (4) | + | + | o | + | + | − | − |

| TCE (5) | + | R | R | − | − | + | + |

| THPM (6) | − | o | + | + | − | R | |

| Ph (7) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| DFE (8) | − | − | + | − | o | + | |

| TFE (9) | + | + | o | + | − | + | + |

| HFIP (10) | + | R | R | + | − | + | + |

| TFMB (11) | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Oxetane (12) | − | − | + | − | R | R |

For each condition, the dansylate was assessed to be stable (+), give partial cleavage (o), complete cleavage (−), or react to form other products (R).

1M NaI in acetone, reflux, 16h;

20% piperidine/DMF, rt, 16h;

0.3 mmol/ml NaN3 in DMSO, 70°C, 16h;

excess Fe(0), 2:2:1 EtOH:HOAc:H2O, 50°C, 1h;

9:1 CH2Cl2/2 M NaOH in MeOH, rt, 16h;

48% HBr, reflux, 2h;

0.1M BBr3 in CH2Cl2, rt, 2h.

Sodium iodide in refluxing acetone is a non-basic nucleophile that deprotected nBu, iBu, iPr, oxetane, THPM, and DFE esters. While THPM and DFE showed greater stability to cleavage among this group, they nonetheless succumbed under conditions commonly used in the Finkelstein reaction. In contrast, Neo, TFE, TCE, Ph, HFIP and TFMB were inert.

Piperidine (20% solution in DMF) is a basic nucleophile that readily cleaved the nBu ester, and reacted with the TCE ester to form a sulfonamide. The TCE sulfonate ester has been previously described to be labile to nucleophilic amines such as piperidine, and to be prone to formation of dichlorovinyl esters when used as a protecting group for sulfates.7 Prolonged treatment with piperidine (overnight, rt) also resulted in the complete cleavage of iPr, iBu, DFE, and oxetane, and gave partial cleavage of THPM. HFIP yielded a complex mixture of products that were not identified. Only Neo, TFE, Ph and TFMB survived intact.

Neo sulfonates are known to be deprotected with small nucleophiles at high temperature, such as overnight treatment with tetramethylammonium chloride in DMF at 160°C.6 Milder cleavage of Neo sulfates has been reported with a slight excess of NaN3 in DMF at 70°C.12 Under similar conditions in DMSO, TFMB was cleaved and partial cleavage of Neo and TFE sulfonates was observed (Table 1). HFIP rapidly reacted to form a side-product, presumably the sulfonyl azide. TCE was more stable, but yielded the same side-product. Heating to 100°C completely cleaved Neo and TFE; only Ph was inert to these conditions.

Treatment with NaOH under non-aqueous conditions in 9:1 DCM/MeOH13 at room temperature cleaved HFIP and TCE in under an hour. Interestingly, HFIP underwent a very rapid transesterification to the methyl ester prior to hydrolysis. Neo esters were stable to these conditions, while Ph, TFMB, and even TFE sulfonate esters were cleaved after overnight incubation at room temperature. Cleavage of TFE sulfates has previously been reported to require refluxing with potassium t-butoxide in t-butanol.14

All of the sulfonate esters evaluated in this work were stable to mildly reducing conditions such as NaBH4. TCE sulfonates have been reported to be cleaved by reduction with zinc,7 and in this study TCE was the only sulfonate found to be removed by reduction with iron (Table 1).

Most sulfonates are stable to moderately acidic conditions. Only the iPr ester was found to be labile to TFA at rt for 16h. The lability of the iPr group is presumably due to formation of a stabilized secondary carbocation.

Hot strong acids cleave most sulfonates. Even Neo has been reported to be labile to overnight reflux in 6M HCl.7 Cleavage under these conditions is presumably due to methyl migration.15 In this study, it was found that refluxing in 48% HBr for two hours also cleaved Neo, as well as iPr, nBu, iBu, THPM, and TFMB. DFE was partially cleaved under these conditions, while oxetane 12 reacted with HBr to open the oxetane ring, but interestingly did not cleave to the sulfonate. Only TCE, Ph, HFIP and TFE survived intact. Similarly, treatment with concentrated sulfuric acid at room temperature for 90 minutes cleaved Neo and TFMB dansylates, but not TCE, HFIP, TFE or Ph.

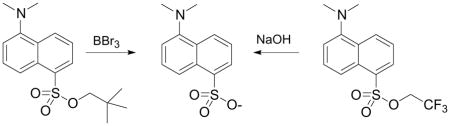

Screening of Lewis acids revealed that the Neo group can be removed under even milder conditions. The Lewis acid BBr3, commonly used to cleave aryl methyl ethers, was found to rapidly remove Neo in less than 15 min at 0°C. Oxetane 12 formed the ring-opened brominated product, as was observed in HBr. These conditions also removed TFMB, but not TCE, HFIP, DFE, TFE, or Ph.

In some circumstances, Neo has been reported to be cleaved under less acidic solvolysis conditions. For example, Liu et al.16 have found that Neo protection of a difluoro-sulfotyrosine residue within a peptide can be removed by extended (4–5 day) treatment with 0.1% TFA. In this case, the fluorinated sulfonate is expected to increase the rate of solvolysis. Similarly, Simpson et al.17 have recently reported that Neo sulfates in peptides can be cleaved by treatment with ammonium acetate (2M, 37°C, 6h). However, these conditions had no effect on Neo dansylate, even at 60°C, possibly due to poor solubility. When dissolved in DMSO, diluted with 2M ammonium acetate, and heated at 100°C for 2h, only partial cleavage was effected.

Six esters are stable to sodium iodide: Neo, TFE, TCE, Ph, TFMB, and HFIP (Table 1). To examine their stability to other reaction conditions on a preparative scale, the respective p-toluenesulfonyl esters (tosylates) were prepared.

Treatment with 20% piperidine in DMF is well-tolerated by TFE, Ph, Neo, and TFMB tosylates 13–16 (Table 2). On the other hand, the TCE ester 17 reacts to form p-toluenesulfonyl piperidine (TsPip),7 and the HFIP ester 18 gives a complicated mixture of products.

Table 2.

Stability of p-toluenesulfonate esters (tosylates).

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R | 20% piperidine/DMFa | NaOHd | BBr3f |

| TFE 13 | Stable (95% 13)b | Cleaved (82% NaOTs)e | Stable (100% 13)b |

| Ph 14 | Stable (97% 14)b | Cleaved (72% NaOTs)e | Stable (95% 14)b |

| Neo 15 | Stable (93% 15)b | Stable (95% 15)b | Cleaved (0% 15)b |

| TFMB 16 | Stable (92% 16)b | Cleaved (65% NaOTs)e | Cleaved (0% 16)b |

| TCE 17 | Cleaved (25% 17, 75% TsPip)c | Cleaved (80% NaOTs)e | Stable (100% 17)b |

| HFIP 18 | Cleaved (mixture) | Cleaved (82% NaOTs)e | Stable (100% 18)b |

16h, rt;

Isolated recovery of starting material;

Estimated from NMR of the crude material;

2 eq NaOH in 9:1 DCM:MeOH, 16h, rt;

Isolated product;

3 eq BBr3, CH2Cl2, 0°C, 2.5h.

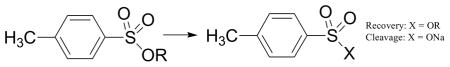

Treatment at room temperature with 2 eq of NaOH in 9:1 DCM/MeOH cleaves most of the tosylates; only Neo survives (Table 2). This deprotection method is particularly useful, as the precipitated sulfonate can be easily separated by filtration and/or extraction. In the case of 16, simple filtration afforded pure sodium p-toluenesulfonate (NaOTs). For 13, the filtered product was contaminated with sodium trifluoroethoxide, but could be purified by subsequent acidification and removal of the trifluoroethanol. Alternatively, extraction rather than filtration affords pure NaOTs.

Conversely, treatment with 3eq of BBr3 at 0°C cleaves both Neo and TFMB tosylates, but leaves TFE, Ph, HFIP and TCE tosylates unaffected. Complete cleavage of 15 and 16 could also be achieved with 1 eq of BBr3 at −78°C. No neopentyl bromide or alcohol was recovered, suggesting that methyl migration occurred during the deprotection.15

Replacement of BBr3 with the milder Lewis acid BCl3 was equally effective, allowing the isolation of NaOTs in 92% yield after treatment of 15 with 1 eq of BCl3 for 30 minutes at 0°C.

Overall, Neo, TFE, and Ph groups are the most broadly stable sulfonate protecting groups. Ph exhibits the highest stability to nucleophiles, even hot NaN3. TFE and Ph are cleaved under basic conditions, while Neo is complementary in its stability as it is cleaved by hot aqueous acid or strong Lewis acid treatment (Table 1). TFMB sulfonates can be cleaved under acidic or basic conditions, yet exhibit high stability to most nucleophiles. TCE and HFIP sulfonates are poorly stable and reactive under basic conditions, but are highly stable to iodide and acidic conditions. TCE esters are also uniquely labile to reducing conditions (Table 1).3

These screening results have established the intrinsic lability of sulfonate esters based on commercially-available alcohols, and can serve as a guide for the judicious selection of a sulfonate protecting group. Moreover, two mild cleavage conditions have been described that together cleave virtually all sulfonate protecting groups, at or below room temperature. Most sulfonates, including TFE and Ph, can be cleaved at room temperature with NaOH under non-aqueous conditions. Sulfonates that are prone to solvolysis in hot protic acid, such as Neo and TFMB, can be cleaved with a stoichiometric amount of BBr3 or BCl3, well below room temperature. Finally, the general stability of fluorinated sulfonate protecting groups suggests that, like the neopentyl group, they are suitable platforms for the construction of protecting groups with engineered lability.

Experimental Section

General procedure for the synthesis of dansyl sulfonate esters 1–12

Dansyl chloride (135 mg, 0.5 mmol) and an alcohol (0.5 mmol) were dissolved in 2 ml CH2Cl2. DABCO18 (67.5 mg, 0.6 mmol) in 1 ml CH2Cl2 was added, resulting in rapid warming and precipitate formation. After completion, the reaction was directly purified by silica gel flash chromatography (0–25% ethyl acetate in hexanes).

5-Dimethylamino-naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid 2,2,2-trifluoro-ethyl ester (TFE dansylate, 9)

Yellow oil (147 mg, 88%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.66 (dt, 1H, J = 8.4, 1.2 Hz), 8.28 (dd, 1H, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz), 8.22 (dt, 1H, J = 8.4, 1.2 Hz), 7.63 (dd, 1H, J = 7.6, 8 Hz), 7.56 (dd, 1H, J = 7.6, 8.4), 7.24 (m, 1H), 4.31 (q, 2H, JHF = 8 Hz), 2.89 (s, 6H). 19F-NMR (CDCl3): δ −74.06 (t, JHF = 8 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 152.2, 132.8, 131.1, 130.3, 130.1, 130.0, 129.4, 123.1, 122.1 (q, 1JCF = 275 Hz), 119.2, 116.1, 65.0 (q, 2JCF = 38.1 Hz), 45.6. HR-EIMS m/z calculated for C14H15F3NO3S: 334.0725, found: 334.0706.

General procedure for the synthesis of p-toluenesulfonate esters 13–18

p-Toluenesulfonyl chloride (1.9 g, 10 mmol) and an alcohol (10 mmol) were dissolved in 15 ml CH2Cl2. DABCO (1.35g, 12 mmol) in 5 ml CH2Cl2 was added, resulting in rapid warming and precipitate formation. After completion, 3 ml of 1M NaOH was added and the reaction was diluted into 100 ml ethyl acetate. The organic layer was extracted with 5% NaHCO3 (3 × 50 ml), 0.1M HCl (3 × 50 ml), water (25 ml), and brine (25 ml). The solvent was dried with sodium sulfate and removed in vacuo.

Toluene-4-sulfonic acid 2,2,2-trifluoro-1-phenyl-ethyl ester (TFMB tosylate, 16)

White powder (2.94 g, 89%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.65 (m, 2H), 7.4–7.27 (m, 5H), 7.21 (m, 2H), 5.66 (q, 1H, J = 6.4 Hz), 2.39 (s, 3H). 19F-NMR (CDCl3): δ −76.48 (d, 3JHF = 5.6 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 145.6, 133.2, 130.5, 129.94, 129.85, 128.8, 128.3, 128.1, 122.5 (q, 1JCF = 279 Hz), 78.3 (q, 2JCF = 34.4 Hz), 21.8. HR-EIMS m/z calculated for C15H13F3O3SNa: 353.0435, found: 353.0431.

Cleavage of trifluoroethyl p-toluenesulfonate

To a solution of 13 (254 mg, 1 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 ml), was added 2M NaOH in MeOH (1.1 ml, 2.2 eq). After stirring for three hours at room temperature, significant precipitation was observed. Water (5 ml) was added, and the aqueous layer extracted. The aqueous layer was then neutralized with 10% H2SO4 and dried by rotary evaporation. The resulting solid was taken up in MeOH (5 ml). After removal of the insoluble Na2SO4 by filtration, rotary evaporation afforded sodium p-toluenesulfonate (153 mg, 79%) as a white powder. 1H-NMR (CD3OD): δ 7.72 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 8 Hz), 2.36 (s, 3H). 1H-NMR (D2O): δ 7.53 (d, 2H, J = 8 Hz), 7.20 (d, 2H, J = 8 Hz), 2.22 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (CD3OD): δ 142.3, 140.6, 128.6, 125.8, 20.2. 13C-NMR (D2O): δ 142.7, 139.5, 129.6, 125.5, 20.6. Spectral data were identical to the commercially available material.

Cleavage of neopentyl p-toluenesulfonate

A solution of 15 (242 mg, 1 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 ml) was cooled to 0°C in an ice bath. Boron trichloride (1 ml, 1M in CH2Cl2, 1 eq) was added dropwise and the solution was stirred on ice for 30 minutes. The volatiles were removed under vacuum. Water (5 ml) was added, and the solution was basified with 1M NaOH. The solution was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 5 ml). The aqueous layer was removed in vacuo to afford a white solid. To this solid was added MeOH (5 ml). Filtration of the insoluble material followed by a short silica gel column (0–15% MeOH/CH2Cl2) afforded 179 mg of sodium p-toluenesulfonate (92%). Spectral data were identical to the authentic material as reported above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM087460-02).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Greene TW, Wuts PGM. Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. 3. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie M, Widlanski TS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;37:4443. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musicki B, Widlanski TS. J Org Chem. 1990;55:4231. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wrobel J, Green D, Jetter J, Kao W, Rogers J, Perez MC, Hardenburg J, Deecher DC, Lopez FJ, Arey BJ, Shen ES. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:639. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGeary RP, Bennett AJ, Tran QB, Prins J, Ross BP. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts JC, Gao H, Gopalsamy A, Kongsjahju A, Patch RJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:355. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali AM, Hill B, Taylor SD. J Org Chem. 2009;74:3583. doi: 10.1021/jo900122c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seeberger S, Griffin RJ, Hardcastle IR, Golding BT. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:132. doi: 10.1039/b614333d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hine J, Ghirardelli R. J Org Chem. 1958;23:1550. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanack M, Ullmann J. J Org Chem. 1989;54:1432. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagiwara T, Tanaka K, Fuchikami T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8187. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson LS, Widlanski TS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1605. doi: 10.1021/ja056086j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theodorou V, Skobridis K, Tzakos AG, Ragoussis V. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:8230. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proud AD, Prodger JC, Flitsch SL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:7243. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich IL, Diaz AF, Winstein S. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:5635. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu S, Dockendorff C, Taylor SD. Org Lett. 2001;3:1571. doi: 10.1021/ol0158664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson LS, Zhu JZ, Widlanski TS, Stone MJ. Chem Biol. 2009;16:153. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartung J, Hünig S, Kneuer R, Schwarz M, Wenner H. Synthesis. 1997:1433. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.