When a product slips in status from “must have” to “don’t need,” it is generally tossed on the scrapheap of consumer history. Just ask the people who invented the floppy disk. According to some health experts, the foreskin is the floppy disk of the male anatomy, a once-important flap of skin that no longer serves much purpose. But the foreskin also has many fans, who claim it still serves important protective, sensory and sexual functions.

“Every mammal has a foreskin,” says Dr. George Denniston, founder of Doctors Opposing Circumcision, an organization based in Seattle, Washington, with members across the United States and in other countries, including Canada. Many people “don’t understand the value of the foreskin,” adds Denniston.

Medical professionals have been debating the value of the foreskin for many years. In 1949, British physician Dr. Douglas Gairdner explored the “fate of the foreskin” in an oft-cited paper in which he noted that some of the health problems prompting adult men to seek circumcision, including phimosis (trouble retracting foreskin) and balanitis (inflammation of the glans), do not apply to infants (BMJ 1949;2:1433–7).

He also weighed the existing evidence supporting claims that circumcision prevented other medical conditions, coming to the conclusion that, at the time, a reduction in cases of penile cancer was the only medical reason “commonly advanced for the universal circumcision of infants capable of withstanding critical scrutiny.”

Furthermore, Gairdner noted, the foreskin plays an important protective role in newborns. “It is often stated that the prepuce is a vestigial structure devoid of function,” he wrote. “However, it seems to be no accident that during the years when the child is incontinent the glans is completely clothed by the prepuce, for, deprived of this protection, the glans becomes susceptible to injury from contact with sodden clothes or napkin.”

That was hardly the final word on the foreskin in medical research. Fast-forward several decades, to the 1980s, and you’ll find influential research that suggested neonatal circumcision could reduce urinary tract infections in male infants by a whopping 90% (Pediatrics 1985;75:901–3 and Pediatrics 1986;78:96–9). This data prompted other researchers to ponder if the prepuce was a mistake of nature (Lancet 1989;1:598–9).

Is the foreskin a redundant piece of skin useful only to viruses, or does it still serve important protective, sensory and sexual functions?

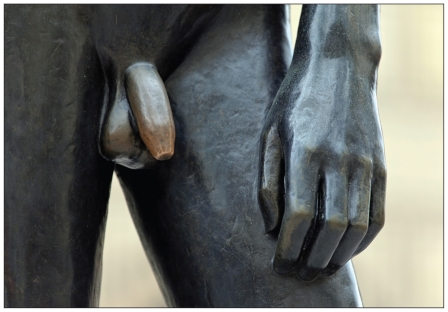

Image courtesy of © 2011 Thinkstock

The pro-prepuce crowd, however, says these and other health problems are better addressed through such activities as education on proper hygiene. And there is much to lose, they claim, when the penis ditches its hood, not the least of which is sexual satisfaction. Though research in this area has yielded inconsistent results, Denniston, for one, has no doubt that the foreskin contains tissue with erogenous properties.

In particular, an area called the “ridged band,” the wrinkly skin at the end of the foreskin, is loaded with nerve endings that are stimulated by motion during intercourse or masturbation. If a man is circumcised as an infant, says Denniston, he has been robbed of sensitivity without his consent.

“The ridged band is important for sexual joy. No one has a right to take that away from someone.”

The foreskin also protects a man’s female sexual partners, says Denniston. First, an intact penis glides in the foreskin during intercourse, reducing friction. Second, the exposed glans of a circumcised penis becomes coarser over time, a process known as keratinization, and is more abrasive to the internal mucous membrane of the vagina.

“You take the foreskin away and let the glans callus and you end up irritating the hell out of the vaginal mucosa,” says Denniston. “Everyone in the US uses lubricants because the basic function of sexual intercourse has been disrupted.”

Some medical researchers, however, claim circumcised men enjoy sex just fine and that, in view of recent research on HIV transmission, the foreskin causes more trouble than it’s worth. Data from a series of high-profile clinical trials in Africa suggest that men cut their chances of contracting HIV by more than half if they are circumcised (PLoS Med 2: e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298 and Lancet 2007;369:643–56 and Lancet 2007;369:657–66).

There is still no consensus, however, on exactly how the foreskin promotes the transmission of HIV.

One hypothesis is that the foreskin simply provides more surface area and therefore more cells that are susceptible to infection, as Dr. Minh Dinh, assistant professor in medicine–infectious diseases at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, posited in a recent review of prevailing theories (Am J Reprod Immunol 2010;65:279–83).

“The virus needs to find a cell to infect,” says Dinh. “It has to find target cells.”

Another theory is that viruses much prefer the damp area under the foreskin to the dryer surface of an exposed glans. “You have this layer of skin that retracts,” says Dinh. “That creates an environment that is dynamic. It is also a warm, moist environment that may allow viral particles to linger longer on the penis, which give the cells there more time to take in the particles.”

The foreskin may also have certain structural characteristic relating to its barrier function and permeability that make it more susceptible to viral infection. Whatever the reason, the benefits of circumcision are apparent, says Dinh, while the benefits of the foreskin are anything but.

“There are no health benefits to having foreskin,” says Dinh. “Not that I’m aware of.”

Editor’s note: Second of a six-part series:

Part I: Circumcision indecision:

The ongoing saga of the world’s most popular surgery (www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.109-4021).