Abstract

Background:

Canada’s Common Drug Review was implemented to provide publicly funded drug plans (provincial and federal) with a transparent, rigorous and consistent approach for assessing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of new drugs. We compared uptake of drug coverage across jurisdictions before and after the implementation of the Common Drug Review.

Methods:

Using the IMS Brogan formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database, we identified new drug products in Canada five years before and five years after the first recommendation was made by the Common Drug Review. For each jurisdiction, we compared the proportion of drugs listed, the median time-to-listing and the agreement between the listing decisions of the drug plans and the recommendations of the Common Drug Review.

Results:

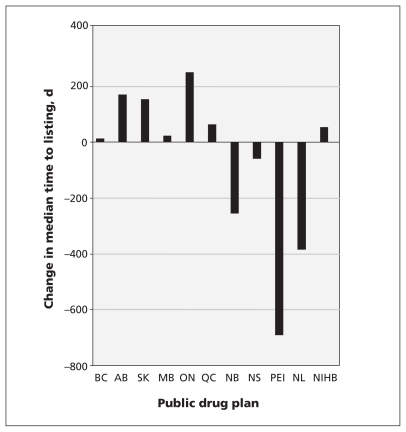

We identified 198 new drugs approved for use in Canada between May 26, 1999, and May 27, 2009, of which 53 had a recommendation from the Common Drug Review. The proportion of drugs listed decreased after the introduction of the Common Drug Review for all participating drug plans (81.1% to 71.3% overall [p ≤ 0.01 for all plans, with the exceptions of Ontario and Quebec [p = 0.07]). The change in median time-to-listing between the periods before and after the Common Drug Review varied by jurisdiction, ranging from a decrease of 691 days to an increase of 250 days. The change in median time-to-listing was not statistically significant for most jurisdictions, with the exceptions of Saskatchewan (increased, Mann–Whitney U test p = 0.01) and New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador (all decreased, Mann–Whitney U test p < 0.01).

Interpretation:

There was a decline in the proportion of new drugs listed after the introduction of the Common Drug Review for both participating and nonparticipating jurisdictions. The introduction of the review was associated with a decreased time-to-listing for certain smaller provinces.

Canada’s publicly funded drug plans were responsible for about 39% of the forecasted $31 billion of drug-related expenditures in 2010.1 There are 19 public drug plans in Canada, each attempting to manage the use of drugs and associated expenditures through various policies, including formulary listings and restrictions. Before 2003, each jurisdiction independently reviewed evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness for new drug products submitted by manufacturers in an effort to secure formulary listing. To standardize this process across drug plans, eliminate duplication and maximize expertise and resources, the Common Drug Review was established.

The Common Drug Review is administered by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.2 Briefly, all Canadian provinces and territories, except for Quebec, and several federal drug plans (Federal Health-care Partnership, Department of National Defence, Veterans Affairs Canada and the Noninsured Health Benefits Program) participate in the process. A review team consisting of internal and external experts from various disciplines, such as pharmacy, epidemiology, medicine, health economics and information science, conduct a systematic literature review and prepare a clinical and economic report for the Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee. This committee evaluates the comparative benefits and costs of the drugs under consideration and provides listing recommendations to participating drug plans. Recommendations are specific (list without conditions, list with conditions, list in a similar manner to other drugs in the same class or do not list). In addition, although a specific price is considered for the analysis of cost-effectiveness, each jurisdiction is able to negotiate its own pricing agreement. Although the general rule of thumb is that “no means no,” publicly funded drug plans are not required to follow the committee’s recommendations, since they must also consider their jurisdiction’s own health care priorities, available resources and the precedence of previous decisions made by the formulary.2,3

Several reports have summarized the proportion of drugs listed on public drug plans with a recommendation from the Common Drug Review and various aspects of time-to-listing; however, these reports are limited in their scope and the period assessed.4–8 We previously reported that the proportion of drugs listed decreased significantly and that the median time-to-listing increased significantly after the introduction of the Common Drug Review in Alberta.8 To evaluate whether those results are representative of other Canadian jurisdictions, we compared the proportion of new drugs listed and their time-to-listing for all provincially funded drug plans and one federally funded drug plan participating in the Common Drug Review within the five years before and the five years after the first recommendation was made (May 27, 2004). We examined Quebec separately, as they have chosen not to participate in the Common Drug Review and serve as a control comparison for our analysis. In addition, we evaluated the agreement between recommendations made by the Common Drug Review and formulary decisions made by the drug plans.

Methods

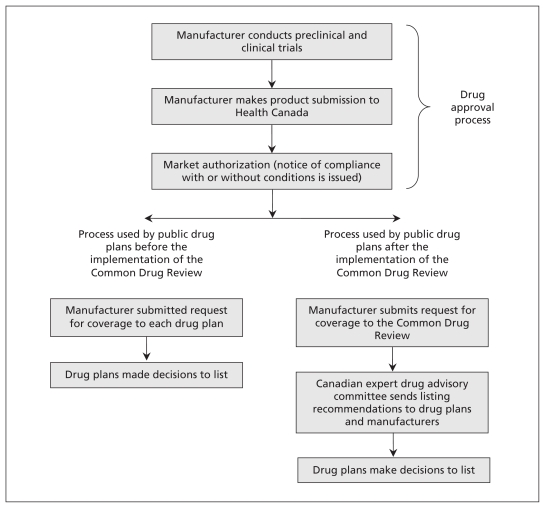

We identified all new drugs approved in Canada that received a notice of compliance between May 26, 1999, and May 27, 2009, using IMS Brogan’s formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database.4 A notice of compliance is issued by Health Canada and shows that a drug product has been authorized for marketing and approved for use in Canada. This process is distinct from the role of the Common Drug Review, which is not involved in approving drugs (Figure 1). The database contains detailed formulary data for all single-source innovator (brand-name) drugs approved for sale in Canada between January 1993 and February 2010. The information available for each drug included listing status, time-to-listing, date product was launched, date notice of compliance was issued, status of submission to the Common Drug Review, active ingredient(s), dose and dosage forms. Noninnovator drugs, drugs used exclusively in hospitals and most nonprescription drugs are not included in the database. Data for all 10 provincial formularies and the formulary for the Noninsured Health Benefits program were available. Drugs were categorized into two mutually exclusive groups: (i) drugs with a notice of compliance dated up to five years before the first recommendation of the Common Drug Review (May 26, 1999, to May 26, 2004) and (ii) drugs with a notice of compliance dated up to five years after the first recommendation (May 27, 2004, to May 27, 2009).

Figure 1:

Overview of the process for approving and reviewing drugs before and after the implementation of Canada’s Common Drug Review.

To provide relatively equal comparisons between periods and drug plans, we included the drug with the earliest notice of compliance and all subsequent products with identical active ingredients (similar dosage forms [e.g., sublingual tablet and immediate release tablet] were excluded). We further excluded 93 drugs that were not likely to be listed on a publicly funded drug formulary or were covered under a specialized drug program. These drugs included antiretroviral agents (n = 21), neoplastic agents (n = 24), over-the-counter agents (n = 3), vaccines (n = 20), blood products (n = 1), drugs that had been withdrawn from the market (n = 9) and products used only in hospitals (n = 15).

We gathered detailed information on listing recommendations from the Common Drug Review’s database, available on the website of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health.2 Where a drug had more than one recommendation for the same indication, only the latest recommendation was used in our analysis. If a drug contained the same active ingredient and was reviewed more than once because of a new indication or alternate manufacturer, only the first submission was used in our analysis. Furthermore, we excluded drugs for which a Notice of Compliance had been issued before the first recommendation made by the Common Drug Review (n = 31) and drugs for which a listing decision had been made before the recommendation of the Common Drug Review (n = 3).

Statistical analysis

New drugs approved before and after the introduction of the Common Drug Review were classified according to their eligibility for coverage under public drug plans (full listing, restricted or special authorization, not listed). The proportion of drugs listed and the time-to-listing were compared for drug plans across time frames for all drugs. Time-to-listing was summarized using median times because it is generally positively skewed. For drugs that were given a notice of compliance after the first recommendation was made by the Common Drug Review, we further stratified the time-to-listing based on two additional periods: time from notice of compliance to recommendation (“federal time frame”) and time from recommendation to listing on the drug plan’s formulary (“provincial time frame”). We used χ2 tests to assess differences in the proportion of drugs listed and Mann–Whitney U tests to assess changes in time-to-listing before and after the first recommendation made by the Common Drug Review.

We measured the agreement between the recommendations of the Common Drug Review and the decisions of the drug plan formularies using overall percent agreement, percent discordance and kappa scores. Agreement was calculated by dividing the number of paired observations in agreement by the total number of paired observations. For example, a 67.9% agreement ([11+25]/53 = 67.9%) for British Columbia was based on 11 positive pairs, in which the review recommended a drug to be listed and the province listed the drug, and 25 negative pairs, in which the review’s recommendation was to “not list” and the province did not list the drug.

Kappa scores were calculated by grouping the recommendations of the Common Drug Review and the decisions of the drug plan formularies into mutually exclusive categories of “listed” and “not listed.” We also calculated kappa scores based on the four categories of recommendation defined by the Common Drug Review to capture the variability among the three types of positive recommendations and the decisions made by the formularies of each jurisdiction. Analyses were conducted using StataSE version 11.

Sensitivity analysis

We used additional analyses to test whether certain eligibility criteria influenced the results of our study. First, to account for any institutional adjustments surrounding the implementation of the Common Drug Review, we excluded drugs approved in the year before the review’s first recommendation was made. We also excluded drugs that were approved during the final year of the study to allow drug plans more time to make decisions regarding drug listings. Second, we repeated our analyses by including all drugs previously excluded (i.e., duplicates, antiretroviral agents, neoplastic agents, etc.) within our periods of interest. Third, we stratified our primary analyses by year following the first recommendation made by the Common Drug Review. Finally, we recalculated kappa scores using all recommedations made by the Common Drug Review before May 27, 2009.

Results

There were 198 new innovator drugs identified in the formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database that met our study criteria. Of these drugs, 111 had been issued a notice of compliance before and 87 after the implementation of the Common Drug Review. All of the notices were issued between May 26, 1999, and May 27, 2009.

The drug plans we included that participate in the Common Drug Review listed between 46.8% (52/111) and 65.8% (73/111) of new drugs in the five years before the Common Drug Review made its first recommendation; in the five years after implementation, these plans listed between 11.5% (10/87) and 40.2% (35/87) of new drugs (χ2 test, p ≤ 0.01 for all drug plans except Ontario [p = 0.07]) (Table 1). Furthermore, most of the plans we included in our analysis (9/11) gave a restricted listing to most of the drugs they listed during both periods. Quebec, which has chosen not to participate in the Common Drug Review, listed 72.1% (80/111) of drugs before the first recommendation of the review and 59.8% (52/87) (p = 0.07) of drugs after the first recommendation; the corresponding percentages for drugs with a restriction were 51.3% (41/80) and 69.2% (36/52) (Table 1)

Table 1:

Proportion of drugs listed and median time-to-listing for all drugs and drugs with a restricted listing approved between May 26, 1999, and May 27, 2009, before and after the introduction of the Common Drug Review

| Public drug plan | Drugs listed, no. (%) | Drugs with restricted listing, no. (% of listed drugs) | Median time-to-listing for all drugs, d | Median time-to-listing for drugs with restricted listing, d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Common Drug Review n = 111 |

After Common Drug Review n = 87 |

Before Common Drug Review | After Common Drug Review | Before Common Drug Review | After Common Drug Review | Before Common Drug Review | After Common Drug Review | |

| British Columbia | 52 (46.8) | 22 (25.3) | 37 (71.2) | 12 (54.5) | 549 | 562 | 574 | 454 |

| Alberta | 62 (55.9) | 26 (29.9) | 25 (40.3) | 14 (53.8) | 312 | 482 | 338 | 594 |

| Saskatchewan | 73 (65.8) | 35 (40.2) | 47 (64.4) | 24 (68.6) | 287 | 442 | 319 | 506 |

| Manitoba | 61 (54.9) | 15 (17.2) | 34 (55.7) | 8 (53.3) | 402 | 426 | 447 | 363 |

| Ontario | 54 (48.6) | 31 (35.6) | 31 (57.4) | 18 (58.1) | 443 | 692 | 641 | 815 |

| New Brunswick | 64 (57.7) | 33 (37.9) | 41 (64.1) | 21 (63.6) | 749 | 494 | 742 | 532 |

| Nova Scotia | 61 (54.9) | 31 (35.6) | 39 (63.9) | 19 (61.3) | 470 | 411 | 475 | 438 |

| Price Edward Island | 55 (49.5) | 10 (11.5) | 31 (56.4) | 4 (40.0) | 1308 | 617 | 1585 | 837 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 57 (51.4) | 24 (27.6) | 39 (68.4) | 13 (54.2) | 734 | 349 | 914 | 407 |

| Noninsured Health Benefits Program | 65 (58.6) | 22 (25.3) | 36 (55.4) | 12 (54.5) | 434 | 488 | 549 | 563 |

| Quebec* | 80 (72.1) | 52 (59.8) | 41 (51.3) | 36 (69.2) | 227 | 292 | 237 | 320 |

| Overall† | 90 (81.1) | 62 (71.3) | 78 (86.7) | 51 (82.3) | 486 | 436 | 573 | 471 |

Note: Recommendations of the Common Drug Review are those made on or prior to May 27, 2009. Data on decisions made by drug plan formularies are based on the version of IMS Brogan’s formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database dated February 2010. Source: IMS Brogan, formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database.

Does not participate in the Common Drug Review.

Refers to drugs that were listed on at least one of the drug plans participating in the Common Drug Review.

The median time-to-listing for drugs in participating jurisdictions varied from 287 days to 1308 days before the implementation of the Common Drug Review (Table 1). After the Common Drug Review was introduced, the median time-to-listing ranged from 349 to 692 days. The change in median time-to-listing varied by jurisdiction, ranging from a decrease of 691 days to an increase of 250 days (Figure 2), and was statistically significant for four of the participating drug plans. Saskatchewan saw an increase of 155 days (Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.02), whereas New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador saw decreases in time-to-listing (NB = 255 d, PEI = 691 d and NL = 385 d, Mann–Whitney U test, p < 0.01 for all) (Figure 2). Quebec had a statistically significant increase in the median time-to-listing of 65 days (Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.02).

Figure 2:

Change in total median time-to-listing before and after the implementation of Canada’s Common Drug Review process. NIHB = Noninsured Health Benefits Program.

A total of 53 drugs with a recommendation from the Common Drug Review were included in our agreement analysis, of which 45.2% (24/53) were recommended to be listed in some manner. Participating drug plans listed between 7 and 25 of these drugs (Table 2). Several drugs were listed on formularies despite being given a “do not list” recommendation by the Common Drug Review (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.110670/-/DC1). Quebec listed 12 of the 29 drugs given a “do not list” recommendation by the Common Drug Review. The percent agreement between recommendations and decisions ranged from 60.4% to 96.2%, irrespective of how agreement was defined (Table 2). Kappa scores ranged from 0.28 to 0.88 when agreement was based on list status (listed v. not listed) and from 0.36 to 0.84 when agreement was based on the four recommendation categories (Table 2).

Table 2:

Agreement between 53 of the recommendations made by the Common Drug Review and the decisions to list made by 11 Canadian public drug plans

| British Columbia | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | New Brunswick | Nova Scotia | Prince Edward Island | Newfoundland and Labrador | NIHB | Quebec* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of drugs listed† | 15 | 17 | 21 | 10 | 25 | 22 | 21 | 7 | 15 | 17 | 33 |

| Percent agreement between listed and not listed‡ | 67.9 | 86.8 | 90.6 | 73.6 | 64.2 | 96.2 | 94.3 | 67.9 | 83.0 | 83.0 | 71.7 |

| Percent agreement between recommendation categories‡ | 69.8 | 83.2 | 84.9 | 69.8 | 60.4 | 90.6 | 90.6 | 67.9 | 83.0 | 81.1 | 66.0 |

| “Not listed” among positive recommendations, no. (%) n = 24 |

13 (54.2) | 7 (29.2) | 4 (16.7) | 14 (58.3) | 9 (37.5) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (12.5) | 17 (70.8) | 9 (37.5) | 8 (33.3) | 3 (12.5) |

| “Listed” among negative recommendations, no. (%) n = 29 |

4 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (34.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 12 (41.4) |

| Kappa coefficients (listed v. not listed) | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.31 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.45 |

| Kappa coefficients (recommendation categories) | 0.48 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.48 |

Note: Recommendations of the Common Drug Review are those made on or prior to May 27, 2009. Data on decisions made by drug plan formularies are based on the version of IMS Brogan’s formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database dated February 2010. NIHB = Noninsured Health Benefits Program.

Does not participate in the Common Drug Review.

Drugs with full or restricted listing based on 53 drugs with a recommendation from the Common Drug Review.

See Methods section for calculation of percent agreement.

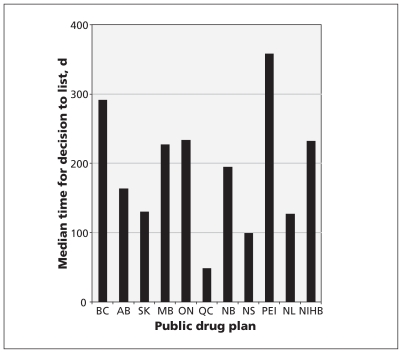

For listed drugs that received a recommendation, the time between when the recommendation was made and when the drug was listed by public drug plans is presented in Figure 3 and Appendix 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.110670/-/DC1). The median provincial time frame (excluding Quebec) ranged from 99 to 358 days. In contrast, before the implementation of the Common Drug Review, public drug plans were responsible for the entire drug-review process, and the average time-to-listing was 778 days in the five years before the program’s inception.

Figure 3:

The median number of days between recommendations being made by the Common Drug Review and decisions made by public drug plans. NIHB = Noninsured Health Benefits Program.

Sensitivity analysis

Our results were unchanged when we excluded data from the year before the implementation of the Common Drug Review and the last year of the study period. When we included all drugs in the formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database, our results remained consistent with our primary analysis in terms of both direction and size (data not shown). The proportion of drugs listed and median time-to-listing for each year following the Common Drug Review’s first recommendation can be seen in Table 3. Finally, kappa scores were consistent when all recommendations made by the Common Drug Review were considered (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.110670/-/DC1).

Table 3:

Proportion of drugs listed and median time-to-listing for each year after the first recommendation issued by the Common Drug Review for drugs approved in Canada between May 27, 2004, and May 27, 2009

| Public drug plan | Drugs listed, no. (%) | Median time-to-listing, d | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 27, 2004–May 26, 2005 (n = 23) | May 27, 2005–May 26, 2006 (n = 19) | May 27, 2006–May 26, 2007 (n = 18) | May 27, 2007–May 26, 2008 (n = 14) | May 27, 2008–May 26, 2009 (n = 13) | May 27, 2004–May 26, 2005 | May 27, 2005–May 26, 2006 | May 27, 2006–May 26, 2007 | May 27, 2007–May 26, 2008 | May 27, 2008–May 26, 2009 | |

| British Columbia | 7 (30.4) | 4 (21.1) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (23.1) | 483 | 778 | 691 | 559 | 353 |

| Alberta | 4 (17.4) | 6 (31.6) | 8 (44.4) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (30.8) | 319 | 474 | 657 | 612 | 304 |

| Saskatchewan | 7 (30.4) | 10 (52.6) | 8 (44.4) | 5 (35.7) | 5 (38.5) | 326 | 1202 | 452 | 493 | 277 |

| Manitoba | 7 (30.4) | 5 (26.3) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.7) | 464 | 350 | 735 | 546 | 336 |

| Ontario | 8 (34.8) | 6 (31.6) | 9 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) | 1 (7.7) | 988 | 765 | 865 | 418 | 281 |

| New Brunswick | 6 (26.1) | 9 (47.3) | 9 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (30.8) | 516 | 792 | 554 | 466 | 295 |

| Nova Scotia | 5 (21.7) | 9 (47.3) | 9 (50.0) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (30.8) | 266 | 424 | 429 | 402 | 353 |

| Prince Edward Island | 4 (17.4) | 4 (21.1) | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 865 | 569 | 429 | NR | NR |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 5 (21.7) | 6 (31.6) | 5 (27.8) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (30.8) | 291 | 535 | 386 | 450 | 243 |

| NIHB | 6 (26.1) | 6 (31.6) | 7 (38.9) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 389 | 574 | 492 | 603 | NR |

| Quebec* | 14 (60.9) | 11 (57.9) | 13 (72.2) | 8 (57.1) | 6 (46.1) | 301 | 342 | 358 | 226 | 238 |

| Overall† | 16 (69.6) | 14 (73.7) | 15 (83.3) | 11 (78.6) | 6 (46.1) | 405 | 483 | 499 | 466 | 290 |

Note: NIHB = Noninsured Health Benefits Program, NR = not reported. Recommendations of the common drug review are those made on or before May 27, 2009. Data on formulary decisions are based on the February 2010 version of the IMS Brogan formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database. Source: IMS Brogan, formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database.

Does not participate in the Common Drug Review.

Refers to drugs that were listed on at least one of the drug plans participating in the Common Drug Review.

Interpretation

Main findings

The proportion of drugs listed decreased significantly after the introduction of the Common Drug Review for all participating drug plans included in our analysis. Time-to-listing decreased for a number of the smaller provinces. Our data suggest that substantial variation exists in the agreement between the decisions made by formularies and the recommendations made by the Common Drug Review.

Comparison with other studies

Several previous studies have examined the proportion of new drugs listed across Canada’s public drug plans.4,6,9,10 Grégoire and colleagues reported that between 28% and 83% of new drugs approved in Canada between 1991 and 1998 (before the implementation of the Common Drug Review) were listed on a provincial formulary.9 In contrast, studies done after the implementation of the Common Drug Review have reported average listing rates of 25% or lower.4,6 Indeed, we found that the number of new drugs listed for reimbursement on public drug plans has decreased substantially since the introduction of the program. This decrease is likely multifactorial and may be partly due to the considerable clinical uncertainty seen in recent drugs submitted for review.11

Our results are relatively consistent with those of other studies evaluating the time from a drug’s approval to its formulary listing.4,6

The positive list rate for the Common Drug Review (i.e., “list,” “list with criteria/conditions” or “list in a similar manner to drugs in the same class”) has been consistently reported at about 45%–55%.3,8,11–13 Indeed, we found a 45.3% (24/53) positive list rate among the 53 drugs that received a recommendation between May 27, 2005, and May 27, 2009.

Our results, based on 53 recommendations, suggest a lower overall percent agreement than previously mentioned in a 2007 report from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.14 Importantly, there are factors beyond the process involved in the Common Drug Review that may have influenced the decisions made by the formularies in different jurisdictions and time-to-listing. Such factors could include interjurisdictional variation in the rigour and procedures of the review process, institutional adjustments or changes at the onset of the Common Drug Review, recommendations of the Atlantic Common Drug Review, and the local values, resources and priorities of each jurisdiction.

Limitations

Time-to-listing is based on the date of approval and not the date of submission to the drug plan or to the Common Drug Review. Thus, substantial lag time between the date a drug was approved and the date it is available may exist. However, we do not expect this to bias our results as the lag times would not be expected to be systematically different between periods.

We are unaware of the extent to which there may have been differences in manufacturers’ submissions to drug plans before the implementation of the Common Drug Review and the circumstances governing a jurisdiction’s decision to accept or reject the recommendations made (e.g., province-specific pricing or listing agreements).

Time for listing decisions in the period after the implementation for the Common Drug Review compared with the period before was shorter; therefore, fewer decisions may have been captured during the later period.

Finally, although we included Quebec as a control, listing decisions in Quebec may have been influenced by the Common Drug Review, as suggested by a lower positive listing rate after the program was implemented.

Conclusion and implications for further research

There was a decline in the proportion of new drugs listed after the introduction of the Common Drug Review, both for participating and nonparticipating jurisdictions. Our findings suggest that the Common Drug Review may have contributed to a streamlining of the process for reviewing drugs for certain jurisdictions. Specifically, patients in the provinces of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador may have benefited with earlier access to new drugs. Any substantial gains in savings or in the efficiency of publicly funded drugs plans to make listing decisions are important factors in maintaining the health and safety of Canadian patients. Future research evaluating the time-to-decision for both positive and negative listings would be an important outcome to measure from the perspective of the public.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank IMS Brogan for providing access to the formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation database.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: John-Michael Gamble contributed to the design, data acquisition, and data analysis and interpretation of this study; he coauthored the first draft of the manuscript and provided critical revisions. Daniala Weir contributed to the data analysis and interpretation of this study; she coauthored the first draft of the manuscript and provided critical revisions. Jeffrey Johnson contributed to the design, data acquisition and interpretation of this study and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dean Eurich contributed to the study design, data acquisition and interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding: John-Michael Gamble receives salary support through a full-time Health Research Studentship from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (AIHS) and a Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Jeffrey Johnson is a Senior Health Scholar with AIHS and Canada Research Chair in Diabetes Health Outcomes. Dean Eurich is a Population Health Investigator with AIHS and a New Investigator with the CIHR. This study was funded in part by a CIHR Team Grant to the Alliance for Canadian Health Outcomes Research in Diabetes (reference no. OTG-88588), sponsored by the CIHR Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes. Jeffrey Johnson is a member of the Expert Committee for Drug Evaluation and Therapeutics for Alberta Health and Wellness. The opinions expressed in this manuscript are the authors’ and not those of Alberta Health and Wellness or the Expert Committee for Drug Evaluation and Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information Drug expenditure in Canada 1985 to 2010. Ottawa (ON): The Institute; 2011. p. 1–154 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Common Drug Review: procedure for Common Drug Review. Ottawa (ON): The Agency; 2011. Available: cadth.ca/media/cdr/process/CDR_Procedure_e.pdf (accessed 2011 Jan. 14). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tierney M, Manns B. Optimizing the use of prescription drugs in Canada through the Common Drug Review. CMAJ 2008;178: 432–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kallah J. Formulary acceptance: monitoring and evaluation. Provincial Reimbursement Advisor 2006;9:57–77 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt G, Gladu V, McDonald-Taylor K, et al. The 2007 Wyatt Health International Comparison. Access to innovative pharmaceuticals: How do countries compare? Oakville (ON): Wyatt Management Consulting; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rovere M, Skinner B. Access delayed, access denied: Waiting for new medicines in Canada. 2009 Report. Vancouver (BC): Fraser Institute; 2009. Available: www.fraserinstitute.org/research-news/display.aspx?id=17807 (accessed 2011 Aug. 8) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scobie AC, MacKinnon NJ. Cost shifting and timeliness of drug formulary decisions in Atlantic Canada. Healthc Policy 2010;5: 100–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamble JM, Eurich DT, Johnson JA. A comparison of drug coverage in Alberta before and after the introduction of the National Common Drug Review process. Healthc Policy 2010;6:e117–44 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grégoire JP, MacNeil P, Skilton K, et al. Inter-provincial variation in government drug formularies. Can J Public Health 2001; 92:307–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anis AH, Guh D, Xh W. A dog’s breakfast: prescription drug coverage varies widely across Canada. Med Care 2001;39:315–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement FM, Harris A, Li JJ, et al. Using effectiveness and cost-effectiveness to make drug coverage decisions: a comparison of Britain, Australia, and Canada. JAMA 2009;302:1437–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lexchin J, Mintzes B. Medicine reimbursement recommendations in Canada, Australia, and Scotland. Am J Manag Care 2008;14: 581–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon M, Morgan S, Mitton C. The Common Drug Review: A NICE start for Canada? Health Policy 2006;77:339–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Submission Brief to House of Commons Standing Committee on Health April 25, 2007. Ottawa (ON): The Agency; 2007. Available: www.cadth.ca/media/media/CADTH_Submission_to_Standing_Committee_on_Health_070409.pdf (accessed 2011 Aug. 8) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.