Abstract

Clinical presentation of an adnexal mass is often non-specific and may mimic a range of gynecological pathology, as well as renal or gastrointestinal causes of lower abdominal pain. While a common entity, its association with a fallopian tube pathology is very uncommon. Imaging such as ultrasound has been diagnostic in the evaluation of a pelvic mass, and has been reported as assisting the diagnosis of fallopian tubal torsion. A pelvic mass of cystic nature can be removed by cystectomy, while treatment options for a torted fallopian tube include surgical detorsion if detected early, or a salpingectomy should there be evidence of necrosis. We report a rare case of fallopian tube torsion complicated by a large hydrosalpinx which was managed by laparoscopic surgery.

Keywords: adnexal mass, laparoscopy, fallopian tube, torsion

Introduction

Adnexal masses are commonly found in both symptomatic and asymptomatic women of reproductive and non-reproductive age. In women of reproductive age, physiologic follicular cysts and corpus luteum cysts are the most common adnexal masses, but the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy must always be considered.1 Other differential diagnoses include endometriomas, pyosalpinx, tubo-ovarian abscesses, and benign neoplasms. Their association with a fallopian tubal torsion (FTT) is an uncommon cause of lower quadrant pain that has been reported to affect primarily adolescents and ovulating women. Risk factors include both intrinsic and extrinsic factors such as pelvic inflammatory disease, tubal ligation, adhesions, ovarian or uterine masses, and trauma.2,3

Case study

A 14-year-old Caucasian nulliparous woman presented with a 3-week history of intermittent left flank pain which radiated down to her left groin. For the previous 24 hours the pain had worsened and she developed symptoms of nausea. She did not complain of any febrile illness, and had no urinary or bowel symptoms. She was menstruating and not on any contraception as she was not sexually active. On examination, she remained hemodynamically stable. Her abdomen was soft to palpation with tenderness on the left hypochondrium. A urine dipstick revealed a large amount of blood. A vaginal examination was not performed.

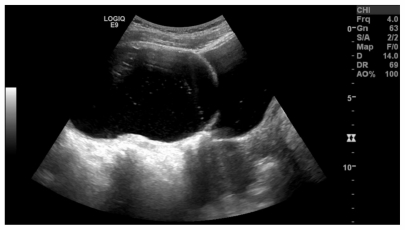

Her complete blood picture was unremarkable. A serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) was negative. A working diagnosis of renal colic was made and the patient was admitted under the urology specialty. A computerized tomography (CT) scan for the kidneys, ureters, and bladder revealed a large cystic lesion measuring 9 × 11 × 12 cm extending from the pelvic cavity up to the level of the umbilicus (Figure 1). A 4 mm calculus was noted in the upper pole of the left kidney with no evidence of hydronephrosis. A pelvic ultrasound was organized to further visualize the origin of the cyst. There were features of septations along the right wall of the cyst, suggesting that it was arising from the right side of the ovary (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A CT abdomen demonstrating the large cystic lesion seen extending from the pelvic cavity up to the level of the umbilicus measuring 9 × 11 × 12 cm indenting the bladder dome.

Figure 2.

A pelvic ultrasound on the longitudinal view demonstrating the large adnexal cyst with septations along the right wall, suggesting an origin from the right ovary.

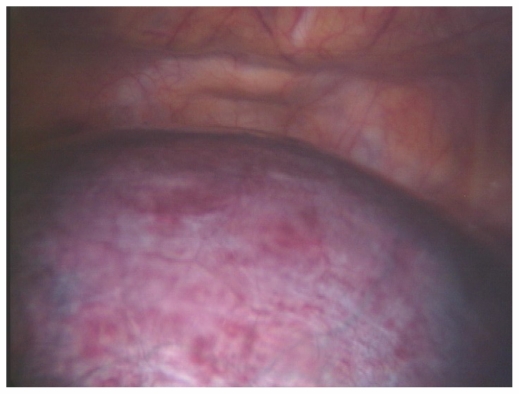

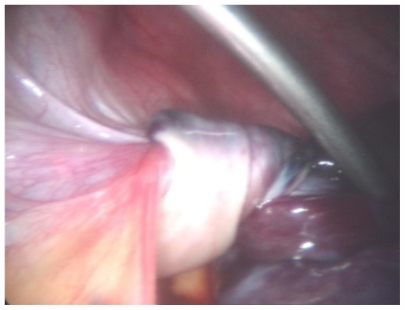

A diagnosis of a large ovarian cyst was made and third party consent was obtained for laparoscopy and drainage of the cyst. Prior to surgery an external vaginal examination revealed an intact hymen and thus a uterine manipulator was not utilized. Laparoscopy was achieved with one 10-mm and three 4-mm ports of entry. Intraoperatively the dome of the cyst was seen to be completely obscuring the pelvic structures (Figure 3). In the visible parts of her abdomen there were no signs of malignancy. The cyst was perforated in a controlled manner close to the abdominal wall in order to avoid spillage. Hemoserous fluid (700 mL) was aspirated, and the internal surface of the cyst was noted to be smooth. After drainage of the cyst, all pelvic structures were visible and the origin of the cyst led to the left adnexa. The left fallopian tube was torted twice with a normal left ovary (Figure 4). Detorsion revealed evidence of hemorrhage and infarction on the distal end (Figure 5). Further inspection revealed a normal uterus and right ovary. A left salpingectomy was performed with preservation of both ovaries and right fallopian tube. Postoperative recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged home the next day and follow-up appointments in our gynecology outpatient department were arranged for the coming weeks. Histopathology confirmed a benign cyst deriving from the fallopian tube with the basic structures extensively replaced by recent and organizing hemorrhage.

Figure 3.

The dome of cyst that appeared hemorrhagic and congested on laparoscopy. It appeared to be completely obscuring the pelvic structures beneath.

Figure 4.

The proximal end of the left fallopian tube which can be seen to be twisted post aspiration of the cyst.

Figure 5.

The distal end of the left fallopian tube with evidence of further torsion, necrosis, and gangrene.

Discussion

While hydrosalpinx are common, FTT remains a rare gynecological disorder. Its incidence in Australia is unknown, but there appears to be a relatively high prevalence in Asian women, as recently reported.4,5 The exact cause of fallopian tube torsion is unknown. Numerous studies have hypothesized possible explanations, including an initial obstruction of adnexal veins and lymphatics, leading to pelvic congestion and edema, enlargement of the fimbrial end, and subsequent partial to complete torsion of the affected tube.2,3

FTT is manifested by unspecific clinical features and uncommon objective findings.5 A delayed diagnosis in our case was due to the clinical history and presentation highly suggestive of a renal colic, with presence of blood in the urine, which may have been a contamination as the patient was menstruating. An abdominal CT was warranted to identify the location of the possible renal calculus. In this case a 4-mm calculus was found in the upper pole of the left kidney which is unlikely to have been the cause of our patient’s presenting symptom as there were no signs of obstruction. Instead, a large pelvis mass of cystic nature was found. We speculate an initial intermittent torsion of the left fallopian tube for the previous 3 weeks which would explain the history of her presenting complaint. Swelling and edema led to a dilatation of the tube and hence a cyst formation. The volume of the cyst increased and further torsion was noted, which led to her casualty presentation. In our case a large hydrosalpinx was formed in the absence of any supporting risk factors for pelvic inflammatory disease.

Ultrasound remains the standard imaging in the evaluation of an adnexal mass,1 and has been shown to be helpful in the diagnosis of a twisted fallopian tube. The characteristic whirlpool sign has been suggested as a specific sign for FTT,6 as well as evidence of reversal or absent flow in color Doppler of the affected tube due to obstruction of the blood supply.7 These features were not visualized in our case, probably due to the large mass effect of the cyst. A simple large ovarian cyst was suspected as the likely diagnosis in the absence of any evidence of infection, as well as its characteristics on ultrasound, which appeared round and anechoic with smooth thin walls. The cyst seen on the two medical imagings in this case represented the enlarged torsed left fallopian tube that obscured the ovary, presenting as a large ovarian cyst to the clinician. The possible septation along the right wall of the cyst suggested an origin from the right ovary, which was misleading as discovered intraoperatively.

The diagnosis of FTT is often made at surgery. Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for the treatment as the early diagnosis may spare the tube and preserve future fertility.5 A salpingectomy was warranted for our patient as surgical detorsion revealed a congested hydrosalpinx and necrotic fallopian tube. While technically challenging, a laparoscopic approach was successful with minimal intervention and reduced postoperative complications.

Conclusion

In the absence of any signs of malignancy and with adequate laparoscopic skills, the presence of a large cystic adnexal mass should never deter the surgeon from a laparoscopy. We achieved an excellent result with minimally invasive surgery, and this was associated with lower rates of hospital stay, peritoneal signs, and a good postoperative recovery. We support the notion that all pre-menopausal women with an adnexal mass should be referred to a gynecologist for further assessment and management. The rare finding of a torted fallopian tube serves as a reminder to the clinician of its uncommon association with a large cystic mass on imaging findings.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Givens V, Mitchell G, Harraway-Smith C, Reddy A, Maness D. Diagnosis and management of adnexal masses. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:815–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krissi H, Shalev J, Bar-Hava I, Langer R, Herman A, Kaplan B. Fallopian tube torsion: laparoscopic evaluation and treatment of a rare gynecological entity. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:274–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernardus RE, Van der Slikke JW, Roex AJ, Dijkhuizen GH, Stolk JG. Torsion of the fallopian tube: some considerations on its etiology. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:675–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong SWA, Suen SHS, Lao T, et al. Isolated fallopian tube torsion: a series of six cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol. 2010;89:1354–1356. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.503870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo LM, Chang SD, Lee CL, Liang CC. Clinical manifestations in women with isolated fallopian tubal torsion; a rare but important entity. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51:244–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijayaraghavan SB, Senthil S. Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube: the sonographic whirlpool sign. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:657–662. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgartel PB, Fleischer AC, Cullinan JA, Bluth RF. Color Doppler sonography of tubal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:367–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1996.07050367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]