Abstract

Obesity has been associated with increased consumption of sweetened beverages and a high-fat diet. We determined whether the composition of the dry pellet offered with liquid sucrose (LS) and lard influenced the development of obesity. We hypothesized that animals offered LS or LS and lard (choice), in addition to chow or purified low fat diet pellet (LFD; 10% fat), would gain more body fat than controls. We compared the effects of LFD vs. chow on voluntary consumption of LS and lard, serum triglyceride (TG), glucose, and body fat over 21 days. Male Sprague Dawley rats (n=10/group) were offered chow, chow+LS, chow choice, LFD, LFD+LS, LFD choice or solid high-sucrose diet (70% sucrose). Energy intakes of rats fed chow, LFD, and high-sucrose diets were similar. Energy intake was increased by 16% in chow+LS, 15% in LFD+LS, 11% in LFD choice, and 23% in chow choice rats. Chow choice rats consumed 142% more lard than LFD choice rats. Fasting glucose increased in all choice rats compared with the chow and high-sucrose diet rats. Fasting TG increased in LFD choice rats and were ~75% higher than those of chow, LFD, or high-sucrose rats. Chow choice had higher carcass fat than chow, chow+LS, and LFD groups however LFD choice was not different from their controls. Another experiment confirmed rats consumed 158% more lard when given chow choice compared to LFD choice. The diet offered to rats with free access to LS and lard influenced the development of obesity, sucrose and lard selection, and TG.

Keywords: chow, purified diet, hyperphagia, energy intake, body composition, macronutrient self-selection

1.0. Introduction

The common rat models used for obesity research include those with a genetic mutation or those that have been fed a high fat diet. Genetic mutations may influence a variety of physiologic and metabolic parameters [1, 2]. For example, Zucker rats with a mutation of the leptin receptor have changes in energy expenditure, immune response, reproduction, glucose homeostasis, thyroid axis, and inflammatory response [3, 4]. The most common model of diet-induced obesity involves rats fed a composite high fat (solid) diet with dietary fat ranging from 30%–60% MJ. These animals generally take 8–12 weeks to become obese and their phenotype is variable [5]. Americans also consume a high fat diet (>30% MJ), [6, 7], but are consuming 20–25% of their energy in fluid form [8, 9] which equates to approximately 2.2 MJ (535 kcal) day [8]. This is alarming because in a previous meta-analysis in humans there was no compensation for energy added to the diet in liquid form. Consumption of energy in liquid form increased total energy intake by 9% and may have increased weight gain. By contrast, 64% of the energy consumed in solid form was compensated for in the diet [10]. The laboratory rat studies described here used a choice diet that involved free access to dry pellet, 30% sucrose solution, and lard which may be more representative of the diet consumed by humans.

The choice diet is unique in that the 30% sucrose solution and lard are not incorporated into the pellet, but are each offered individually (i.e., as a choice). When combined with chow, the physical form of sucrose and fat affect preference because rats consume more energy from sucrose when consumed in liquid form compared to solid, but consume more energy from fat in solid form compared to oil [11, 12]. Liquid sucrose has previously been shown to promote overeating in chow fed rats by Castonguay et al.[13] and Ackroff and Sclafani [14] and lard by Ackroff and Sclafani [14]. The latter study found that a chow, 32% liquid sucrose solution, and fat (vegetable shortening) group did not increase energy intake compared to a chow and liquid sucrose group. The liquid sucrose and chow and the chow, liquid sucrose, and fat groups consumed more energy than the chow and fat and the chow only groups. This coincided with the chow and liquid sucrose group having a similar body weight as the chow, liquid sucrose, and fat group but a higher body weight than the chow and fat and the chow only groups [14]. A similar model of diet induced weight gain has been associated with changes in hypothalamic neuropeptide expression and the development of glucose intolerance and insulin insensitivity [15, 16]. The purpose of the experiments described here was to determine if the composition of the dry pellet (chow vs. purified diet) offered with the sucrose and lard influenced the development of obesity or insulin tolerance which was used as a measure of glucose clearance. We also compared the effects of feeding a purified dry high sucrose diet with those of dry pellet plus liquid sucrose. We hypothesized that the animals offered liquid sucrose or liquid sucrose and lard would gain more body fat than the control animals because of increased energy intake regardless of diet.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Georgia Health Sciences University and followed the recommendations of the NIH Intramural Animal Care and Use program. All rats were housed in a climate controlled room at ~21°C with lights on for 12 hours/day starting at 6 am. In both experiments, male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were individually housed in hanging wire mesh cages.

2.2. Experiment 1: Effects of chow, LFD, high sucrose diet, LS, and choice on body composition

The purpose of this experiment was to establish the changes in body composition and serum metabolic profile of rats offered access to a 30% sucrose solution (w/v; Kroger Sugar, Hood Packing Corporation, Hamlet, NC, USA) or sucrose solution and lard (Armour, ConAgra Foods, Omaha, NE, USA) in addition to a chow or low fat diet pellet (Table 1; LFD: 10% MJ fat, 20% MJ protein, and 70% MJ carbohydrate; D124450B Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA). In order to determine if the form of sucrose influenced the development of obesity in rats, another group was offered solid high sucrose diet (Table 1; 10% MJ fat, 20% MJ protein, and 70% MJ sucrose; D09082001 Research Diets, Inc.). The LFD had similar fat, protein, and micronutrient content as the solid high sucrose diet. During the baseline period, all rats had free access to chow (Harlan Teklad Rodent Diet 8604; 24% minimum protein, 4% minimum fat, 0.14 MJ/g) and water. Following the baseline period, animals were weight matched into 7 groups (n=10): chow, LFD, chow + 30% sucrose solution (LS), LFD + LS, chow choice (chow, LS, and lard), LFD choice (diet, LS, and lard), and solid high sucrose diet. The LS was placed next to the water bottle and the lard was given in a dish inside the cage with the pellet. Body weight was measured every other day. Five hour fasting tail blood samples were collected on day 5 and day 12 for measurement of whole blood glucose (EasyGluco Blood Glucose Monitoring System, US Diagnostics, Inc., New York, NY, USA) and serum total triglycerides (TG; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA, USA). Energy intakes, corrected for spillage, were measured on days 14–18 (5 days). An insulin tolerance test (ITT) was performed on day 19. This was also started at 1pm following a 5 hour fast. At time 0, each rat was injected i.p. with 0.75 units/kg of Humulin® (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and tail blood glucose samples were measured at 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 45 min.

Table 1.

Composition of the diets (g/1055g)

| LFD (D12450B) | High Sucrose Diet (D09082001) | |

|---|---|---|

| Casein | 200 | 200 |

| L-Cysteine | 3 | 3 |

| Corn Starch | 315 | 0 |

| Maltdextrin 10 | 35 | 0 |

| Sucrose | 350 | 700 |

| Cellulose | 50 | 50 |

| Soybean Oil | 25 | 13.5 |

| Lard | 20 | 31.5 |

| Mineral Mix S 100026 | 10 | 10 |

| DiCalcium Phosphate | 13 | 13 |

| Calcium Carbonate | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Potassium Citrate | 16.5 | 16.5 |

| Vitamin Mix V10001 | 10 | 10 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 2 | 2 |

| Energy Density (MJ/g) | 0.016 | 0.016 |

LFD, low fat diet. These diets are from Research Diet, Inc. (New Brunswick, NJ).

On day 21, food was removed at 7am and the rats were decapitated starting at 9:30am. The right side inguinal, epididymal, retroperitoneal, and entire mesenteric fat pads and liver were dissected, weighed, and returned to the carcass. One lobe of the liver was flash frozen for measurement of lipid content [17] and trunk blood was collected. Serum insulin (Rat Insulin RIA kit, Millipore, St. Charles, MO, USA) and leptin (Multi-species Leptin RIA, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) were measured. Carcass composition, less the gastrointestinal tract, was analyzed as described previously [18].

2.3. Experiment 2: Effect of pellet composition on lard and sucrose selection

Since experiment 1 showed that rats offered LFD choice consumed significantly less lard than those offered chow choice, experiment 2 was designed to determine if this was an effect of pellet composition on food selection. Twenty male Sprague Dawley rats were housed as described above and baseline measures were made for 1 week during which all rats were offered chow. Body weight and energy intake were measured daily. The rats were weight matched to a control chow group (n=6) or a chow choice group (n=14). A partial crossover design was utilized. The control chow rats remained on ad libitum chow during the entire experiment. After 31 days, the chow choice group was divided into two weight-matched groups, one remained on chow choice and the other group was offered LFD choice. An ITT was performed on day 27 when all rats were on chow choice and again on day 58 when rats were on different choice diets. The experiment ended on day 62 when the same end point measures were made as described in experiment 1 with the addition of liver glycogen [17], glycerol (Free Glycerol Determination Kit, Sigma St. Louis, MO, USA), and non-esterfied fatty acids (NEFA; NEFA C kit, Wako Chemicals) measurements.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Values are mean ± SEM. For the ITT, the rate of change was calculated as the slope between time 0 and 45 min. Comparisons among groups were performed using a one-way ANOVA and post-hoc analyses with Tukey HSD (Statistica, version 9, StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P ≤ 0.05.

3.0. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

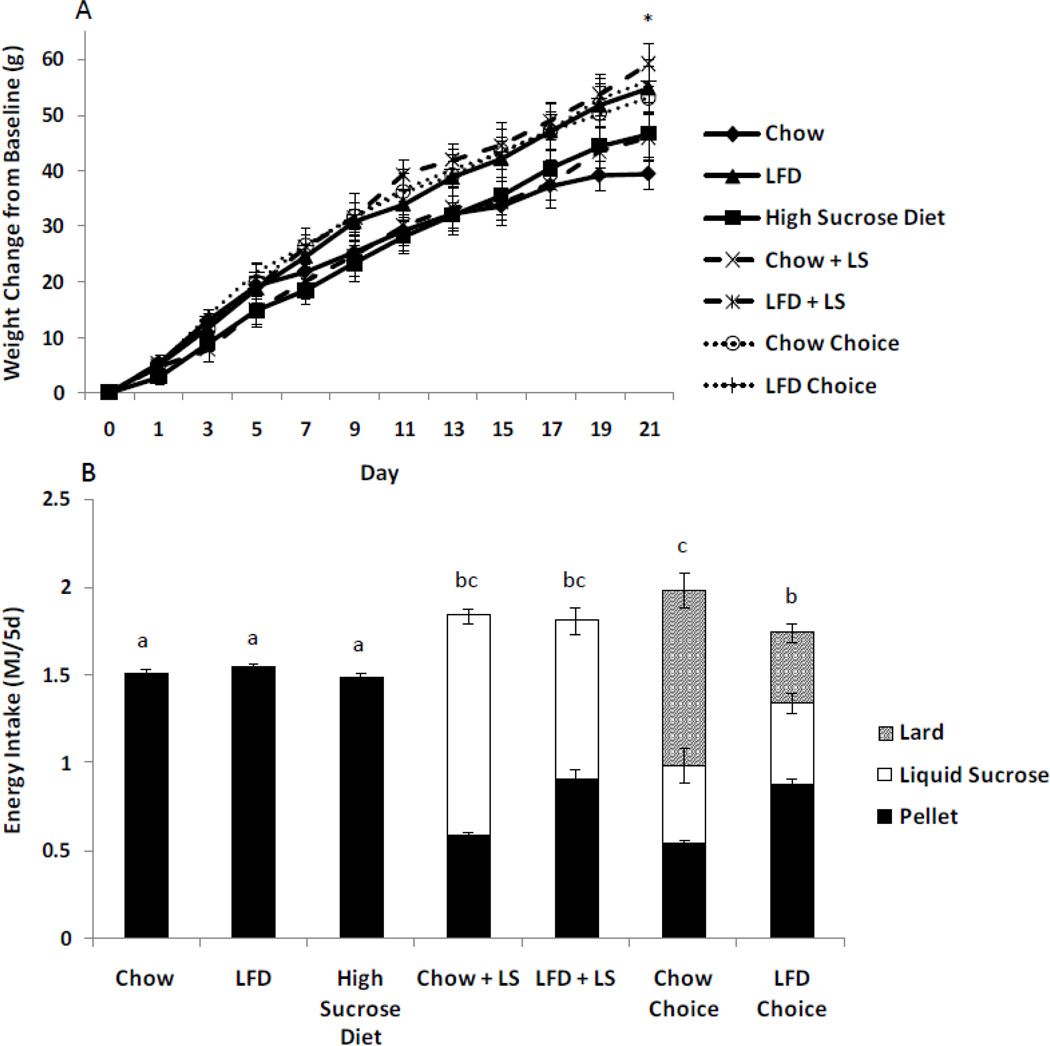

End body weight was not different among groups, but LFD + LS and LFD choice groups gained more weight than did the chow group (Figure 1A). Chow, LFD, and high sucrose diet groups had similar energy intakes (Figure 1B). These were lower than those of the LS and choice groups. Chow choice rats consumed more energy than did the LFD choice group, but intake did not differ from that of the chow + LS and LFD + LS groups. The latter group consumed more pellet, but less sucrose solution than did the chow + LS group (Figure 1B; chow + LS, 1.2 ± 0.1 MJ/5d; LFD + LS, 0.9 ± 0.1). The chow choice group had an increased lard intake (chow choice, 1.0 ± 0.1 MJ/5d; LFD choice, 0.4 ± 0.1), but decreased pellet intake compared with that of the LFD choice group, however the sucrose intakes were similar for the two choice groups (Figure 1B; chow choice 0.5 ± 0.1 MJ/5d; LFD choice, 0.5 ± 0.1). Week 2 fasting glucose was higher in the LFD + LS, chow choice, and LFD choice compared with the chow group (Table 2). No differences in ITT were seen among the groups (Figure 1C). At the end of the experiment, insulin concentration was higher in LFD and LFD + LS compared with the chow group. Also, insulin concentration was higher in LFD + LS than chow, high sucrose diet and LFD choice rats. Serum leptin was higher in the chow choice compared to all other groups (Table 2). Inguinal, epididymal, retroperitoneal and mesenteric fat pad weights are described in Figure 1D. Livers were larger in LFD +LS and LFD choice groups compared with the chow group. Serum TG were higher in the LFD choice compared to chow, LFD, and high sucrose diet rats. Liver lipids were higher in the LFD choice compared to chow, high sucrose diet, chow + LS and LFD group (Table 2). Chow choice had a higher carcass fat content than chow, chow + LS, and LFD groups (Figure 1E). Carcass fat content of LFD, LFD + LS, and LFD choice rats were not different from any other group. Carcass water and ash were not different among groups. Carcass protein was higher in LFD choice, LFD + LS, LFD, and chow + LS groups compared with the chow group (Table 2).

Figure 1. Rats consuming chow, LFD, high sucrose diet, chow + liquid sucrose, LFD + liquid sucrose, chow choice, or LD choice in experiment 1.

(A) Weight gain from baseline of rats in experiment 1. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 9 or 10 rats. Baseline weight was body weight on day 0 of experiment measured before the rats were offered experimental diets. An asterisk indicates significant difference between the LFD + LS and LFD choice groups compared to the chow group. Baseline weight was body weight on day 0 of experiment measured before the rats were offered experimental diets. (B) Energy intakes of rats in experiment 1. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 9 or 10 rats. Letters with a different superscript are different at p<0.05. (C) Blood glucose concentration during an insulin tolerance test performed on day 19 of experiment 1. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 9 or 10 rats. (D) Inguinal, epididymal, retroperitoneal, and mesenteric fat pad weights of rats in experiment 1. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 9 or 10 rats. Letters with a different superscript are different at p<0.05. (E) Carcass body fat content of rats in experiment 1. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 9 or 10 rats. Letters with a different superscript are different at p<0.05.

Table 2.

Characteristics of male rats in experiment 1

| Parameter | Chow | HS Diet | LFD | Chow + LS | LFD + LS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chow Choice | LFD Choice | |||||

| N | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | |

| 10 | 10 | |||||

| End Weight (g) | 347 ± 4 | 355 ± 6 | 364 ± 6 | 354 ± 5 | 367 ± 5 | |

| 361 ± 6 | 365 ± 5 | |||||

| Blood Glucose (mmol/L) | ||||||

| Week 1 | 5.6 ± 0.1a | 5.9 ± 0.2ab | 5.8 ± 0.1ab | 5.7 ± 0.1ab | 6.0 ± 0.2ab | |

| 6.1 ± 0.2ab | 6.4 ± 0.1b | |||||

| Week 2 | 5.5 ± 0.1a | 5.7 ± 0.1ab | 5.9 ± 0.1abc | 5.9 ± 0.1abc | 6.0 ± 0.1bc | |

| 6.3 ± 0.1c | 6.3 ± 0.1c | |||||

| Week 3 | 5.9 ± 0.2a | 6.2 ± 0.2ab | 6.2 ± 0.2ab | 6.4 ± 0.1ab | 6.5 ± 0.1ab | |

| 6.4 ± 0.2ab | 6.6 ± 0.1b | |||||

| Serum | ||||||

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 0.69 ± 0.06a | 0.99 ± 0.14ab | 1.35 ± 0.13bc | 1.18 ± 0.11abc | 1.51 ± 0.13c | |

| 1.06 ± 0.10abc | 0.92 ± 0.10ab | |||||

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 2.38 ± 0.22a | 2.32 ± 0.20a | 2.73 ± 0.27a | 2.79 ± 0.32a | 3.15 ± 0.26a | |

| 4.87 ± 0.60b | 3.33 ± 0.21a | |||||

| TG (mmol/L) | ||||||

| Week 1 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | |

| 6.6 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | |||||

| Week 2 | 3.5 ± 0.4a | 4.9 ± 0.7ab | 4.3 ± 0.5ab | 5.9 ± 0.8ab | 4.9 ± 0.3ab | |

| 5.2 ± 0.5ab | 7.6 ± 0.9b | |||||

| Week 3 | 3.8 ± 0.3a | 4.3 ± 0.5a | 5.9 ± 0.5a | 7.1 ± 0.5ab | 6.9 ± 0.9ab | |

| 7.0 ± 0.9ab | 9.9 ± 1.1b | |||||

| Tissue Weights (g) | ||||||

| Liver | 12.0 ± 0.2a | 13.4 ± 0.5abc | 12.9 ± 0.5abc | 13.2 ± 0.5abc | 14.6 ± 0.3c | |

| 12.4 ± 0.3ab | 13.7 ± 0.5bc | |||||

| Liver Lipid (mg/liver) | ||||||

| 429 ± 6a | 447 ± 14a | 437 ± 21a | 421 ± 16a | 460 ± 15ab | ||

| 487 ± 21ab | 524 ± 21b | |||||

| Carcass (g) | 303 ± 4ab | 315 ± 7ab | 327 ± 5b | 313 ± 5ab | 324 ± 3b | |

| 319 ± 6ab | 328 ± 5b | |||||

| Water (g) | 201 ± 3 | 205 ± 5 | 208 ± 3 | 202 ± 4 | 205 ± 3 | |

| 200 ± 4 | 209 ± 3 | |||||

| Ash (g) | 12 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | |

| 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | |||||

| Protein (g) | 79 ± 1a | 84 ± 2ab | 88 ± 2b | 87 ± 2b | 89 ± 1b | |

| 84 ± 2ab | 89 ± 2b | |||||

HS Diet, High Sucrose Diet; Chow + LS, Chow + 30% Liquid Sucrose; Diet + LS, Diet + 30% Liquid Sucrose; TG, triglyceride.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Values for a given parameter with a different superscript different p<0.05.

3.2. Experiment 2

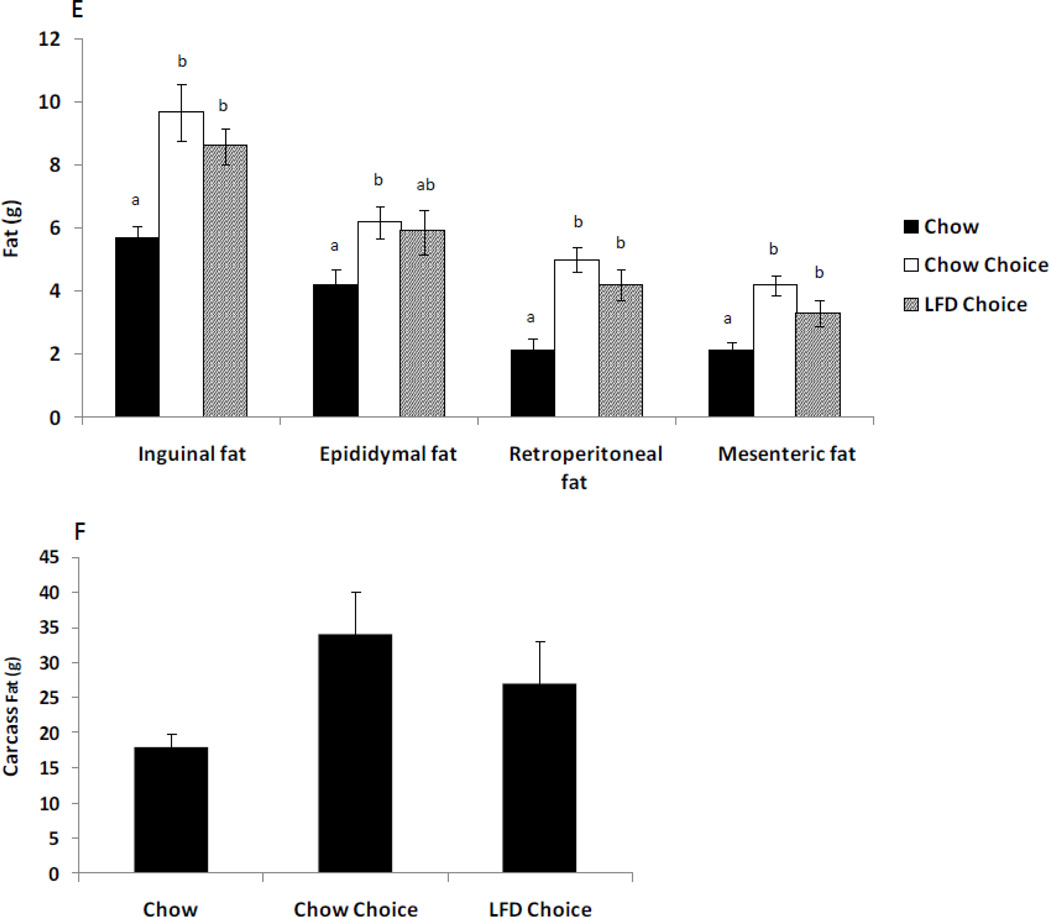

Since experiment 1 showed that rats offered LFD choice consumed significantly less lard than those offered chow choice, this experiment was designed to determine if this was an effect of pellet composition on food selection. Body weight, body weight gain, and energy intake were not different between the chow choice (394 ± 7 g; 65 ± 4 g; 12.30 ± 0.24 MJ/31d) and LFD choice rats (401 ± 8; 68 ± 5g; 12.31 ± 0.44) when they were all offered chow before the switch on day 32. Chow contributed 29% of energy intake, LS 31%, and lard 40% (Figure 2A). On days 32–62 energy intake was significantly increased in both choice groups compared to chow (Figure 2B). However, lard intake was decreased in rats offered the LFD choice rats compared to the chow choice rats. In the second half of the experiment, the chow choice rats consumed 27% of energy as chow, 39% as sucrose, and 33% as lard while the LFD choice rats consumed 58% of energy as LFD, 25% as sucrose, and 16% as lard (Figure 2B). Thus, on average the LFD choice rats consumed 4.86 MJ/31d of lard in the first half of the study while they still had chow but only 1.88 MJ/31d in the second half of the study when they were switched to LFD. LFD choice rats consumed more pellet and less lard, but the same amount of sucrose as chow choice rats (p=0.12). Also during the 2nd phase of the experiment, body weight and body weight gain were higher in the LFD choice rats compared to that of the other groups (day 18 of LFD, day 49 of experiment; Figure 2C). ITT glucose clearance was not different among groups in the first (data not shown) or second portion of the experiment (Figure 2D). At the end of the experiment, there were no differences in serum glucose, TG, glycerol, NEFA, or liver lipids (Table 3). Serum insulin was higher in the LFD choice compared with chow group, and chow choice was not different from either group. Leptin was higher in the choice than chow rats. Inguinal, retroperitoneal, and mesenteric tissue weights were higher in the choice rats compared to the chow group (Figure 2E). Epididymal fat was higher in the chow choice compared to the chow group. Liver weight was higher in the LFD choice group compared with the chow choice and chow groups (Table 3). Liver glycogen was higher in the choice rats compared to the chow rats, but liver lipid was not different among groups. There was a tendency for the chow choice rats to have more fat than the chow group (p=0.07), but the LFD choice group was not different than either group (Figure 2F). Also there was a tendency for the LFD choice to have more lean body mass (water + protein) than the chow choice group (p=0.06) but not the chow group (Table 3).

Figure 2. Rats consuming chow, chow choice, or LFD choice in experiment 2.

(A) Day 1–31 energy intakes of rats in experiment 2. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 6 and 14 rats. Letters with a different superscript are different at p<0.05. (B) Day 32–62 energy intakes of rats in experiment 2. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 6 or 7 rats. Letters with a different superscript are different at p<0.05. (C) Weight gain from baseline of rats in experiment 2. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 6 or 7 rats. Baseline weight was body weight on day 0 of experiment measured before the rats were offered experimental diets. An asterisk indicates significant difference between the choice groups compared to the chow group. Baseline weight was body weight on day 0 of experiment measured before the rats were offered experimental diets. (D) Blood glucose concentration during an insulin tolerance test performed on day 58 of experiment 2. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 6 or 7 rats. (E) Inguinal, epididymal, retroperitoneal, and mesenteric fat pad weights of rats in experiment 2. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 6 or 7 rats. Letters with a different superscript are different at p<0.05. (F) Carcass body fat content of rats in experiment 2. Data are mean ± SEM for groups of 6 or 7 rats.

Table 3.

Characteristics of male rats consuming chow, chow choice, or LFD choice in experiment 2

| Parameter | Chow | Chow Choice | LFD Choice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 6 | 7 | 7 | |

| End Weight | (g) | 415 ± 9a | 434 ± 10a | 456 ± 10b |

| Serum | ||||

| Glucose | (mmol/L) | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.3 |

| Insulin | (ng/mL) | 0.52 ± 0.03a | 0.85 ± 0.16ab | 1.12 ± 0.15b |

| Leptin | (ng/mL) | 2.54 ± 0.21a | 4.84 ± 0.40b | 4.93 ± 0.82b |

| TG | (mmol/L) | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 1.6 | 6.3 ± 0.5 |

| Glycerol | (mg/mL) | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.25 ± 0.05 |

| NEFA | (mEq/L) | 1.34 ± 0.20 | 1.03 ± 0.12 | 1.19 ± 0.27 |

| Tissue Weights | ||||

| Liver | (g) | 12.6 ± 0.5a | 13.8 ± 0.8a | 15.3 ±0.9b |

| Liver Glycogen (mg/liver) | 827 ± 171a | 1833 ± 311b | 1860 ± 326b | |

| Liver Lipid (mg/liver) | 490 ± 14 | 556 ± 31 | 559 ± 41 | |

| Carcass | (g) | 371 ± 8 | 386 ± 10 | 404 ± 11 |

| Water | (g) | 240 ± 4 | 232 ± 4 | 249 ± 7 |

| Ash | (g) | 15 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 16 ± 1 |

| Protein | (g) | 99 ± 6 | 105 ± 1 | 112 ± 5 |

| LBM | (g) | 342 ± 8 | 335 ± 4 | 363 ± 11 |

TG, triglyceride; NEFA, non-esterfied fatty acid; LBM, Lean Body Mass (water + protein)

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Values for a given parameter with a different superscript different p<0.05.

4.0. Discussion

These experiments measured the effect of changing the composition of the dry pellet on selection of liquid sucrose and lard, and we found that composition of the pellet offered to choice rats had a significant effect on food selection and body composition over 21 days. All rats offered LS or the choice diet increased energy intake compared to their controls and the solid high sucrose diet. LFD choice rats increased energy intake by 13% but did not statistically increase measured fat pads or carcass fat compared to their own controls. However all measured LFD choice fat pads increased in weight compared to controls. When rats had chow with a choice of liquid sucrose and lard, they increased their energy intake by at least 30% compared to the chow only group. In experiment 1, there was also a 130% increase in body fat of chow choice rats compared with the chow group during the 3 week experimental period with all the measured fat pads increasing. This rapid gain of body fat contrasts with the 8–12 weeks generally used to induce obesity in rats offered formulated high fat diets (e.g., [5]). The results from this experiment also showed a uniform response within groups because rats on the choice treatment demonstrated a low standard of error unlike the segregation of diet-induced obesity prone and obesity resistant rats reported in some other experimental paradigms [19]. Also, the choice model may be more representative of human food intake than a pelleted high fat diet alone. Thus, the LFD choice may be a good model for diet induced hypertriglyceridemia and elevated liver lipids whereas the chow choice diet model is a practical, inexpensive model of diet-induced obesity with a rapid obesity onset.

Our results confirmed the measures of energy intake of rats described by of Ackroff et al. [14] because the chow + LS group had a similar energy intake to the chow choice group. Chow choice rats compared with the chow + LS rats did not increase serum glucose, insulin, TG or liver lipid over 3 weeks. Although the weights of individual fat pads were not different between chow + LS and chow choice rats, chow choice rats had a greater total carcass fat content than chow + LS suggesting lipid in non-assayed fat pads (e.g., dorsosubcutaneous, perirenal) or in other organs (muscle) were greater. In a previous study examining sucrose form and appetite, 90 day old female CD rats from Charles River that were given chow and sucrose as a solution gained more weight, consumed more energy, and increased body fat and insulin compared with those offered sucrose as a powder [12]. In the studies described here, rats offered chow and liquid sucrose increased energy intake, but not body weight gain compared to controls. By contrast, chow choice rats increased energy intake and body weight gain compared to chow fed animals. The findings of Ackroff et al. were similar in female rats except that they also found increased body weight gain in the chow and liquid sucrose compared to the chow fed group [14].

Previous experiments have shown that diets containing dry sucrose or polycose (glucose polymers) do not result in body weight gain compared to control diet [12, 20], and we found similar energy intake and body weight responses in our experiments. However, our study did not provide the same number of food options for the chow + liquid sucrose group (2 food options) vs. high sucrose diet group (1 food option) which may have affected results. In experiment 1, solid and liquid sucrose were closely matched as a percentage of energy intake but lard was slightly higher in the high sucrose diet vs. LFD (7.0% vs. 4.4%). In experiment 1, the solid high sucrose diet was 70% sucrose while the chow + LS and LFD + LS rats consumed 68% and 50% of energy from liquid sucrose, respectively. The decreased liquid sucrose consumption with LFD compared to chow may be due to the 35% sucrose content found in the LFD. The high sucrose diet did not affect serum glucose, insulin, TG, or the body fat content of the rats over 3 weeks. The LFD + LS group increased serum insulin compared to the solid high sucrose diet. While speculative, the liquid sucrose consumption may cause decreased satiety due to faster gastric emptying rates compared with pellet consumption.

The chow choice rats increased energy intake by 32% over the chow controls while the LFD choice increased energy intake by just 13% compared to the LFD controls. This led to an increase of 130% in body fat of the chow choice group compared to the chow control, but only a 13% increase in the LFD choice group. In experiment 1, the LFD choice group did not statistically increase body fat compared to their controls. Many of the outcome differences resulted from the non-statistical endpoint differences between the chow and LFD groups. Thus, the control values were marginally different between chow and LFD groups causing significant differences in outcome measurements such as body weight, fat pad weights, carcass fat, and TG. This suggests differences in degree of effect over the 3 week period and highlights the need for the appropriate nutritional control groups when performing high fat diet studies or other studies utilizing purified diets. Furthermore, pellet type affects macronutrient selection and may affect study outcomes such as classical conditioning (Pavlovian reinforcement) for items such as sucrose. Others have reported changes in C57BL/6J mouse liver and lung gene expression [21] as well as taste solution preference in mice offered chow or purified diet [22]. In addition, Kozul et al. reported that the AIN 76A diet produced a more consistent background for gene expression studies compared to chow in mice [21].

In our experiments, the source of energy consumed also was different between chow choice and LFD choice rats. The LFD choice group consumed double the amount of energy as pellets but half as much lard compared to the chow choice group. In experiment 1, liquid sucrose consumption was higher in chow + LS than that in LFD + LS rats. These diet selection patterns were consistent whether starting with LFD (unpublished data) and switching to chow or the reverse (Experiments 1 and 2). We have not yet determined the mechanism(s) whereby LFD inhibited sucrose consumption and lard intake. However, rat preference for the LFD compared to chow is a possible explanation. Also, other pre (taste) or post ingestive effects (gastric distress or malaise) with the diets may be present. The LFD and chow contained different types and amounts of protein, carbohydrate including fiber, and fat which likely influenced study outcomes. Also, the LFD diet did not contain soluble fiber. The lack of soluble fiber may be why the TG were higher in the LFD groups. Previously soluble fiber has been shown to lower TG levels [23–25] and reduce liver lipids [23]. Our data suggests that the composition of pelleted feed alters study outcomes dramatically suggesting that the origins of the macronutrient sources rather than just the percentage of each of the three components are important factors. Also, it is possible that the type of fatty acid or carbohydrate in the LFD may be increasing liver lipids [26]. Likely, fatty acid synthase is upregulated in the LFD choice rats. In male CD rats from Charles River, increased serum TG have been previously found at week 6 with purified AIN-76A and AIN-93G diets compared to chow, but over 13 weeks the difference became non-significant [26]. We did not carry out any experiments beyond 3–4 weeks; therefore it is possible that the difference in serum TG between LFD choice and chow choice rats would attenuate over time. This study did not examine the effects of choice on chow vs. purified diets.

As previously described, the rats have a choice of what energy and macronutrients to consume i.e., the diet was provided ad libitum. Thus, over the three weeks, the chow choice rats consumed an average of about ~1.5 g/d of protein whereas the chow fed controls ate ~3.6 g/d. Adult rats that are on a weight maintenance diet need about 7% of energy to come from natural (non purified) protein [27]. Since the chow choice animals consumed chow that provided ~24% of energy from protein, they ate approximately 39% more protein than is needed for a weight maintenance diet suggesting they were not protein deficient. This was confirmed by carcass analysis as the carcass protein content of rats fed diet choice for 62 days was the same as that of chow fed controls. In addition, it is important to note that the rats had a free access to chow and could have consumed more protein if they had the drive to do so.

The increased energy intake and rapid gain of body fat in chow choice rats appears to be an effect of the interaction between the liquid sucrose and lard. In experiment 1, we found that body fat was less if rats were given only a choice of chow and LS compared with chow choice. la Fleur et al. have previously reported that rats offered beef tallow and chow gain less weight than those offered chow, tallow, and liquid sucrose [15]. Therefore, the availability of both liquid sucrose and fat seems more effective for the rapid onset of obesity. la Fleur et al. also found an impaired glucose tolerance in Wistar rats offered a chow choice diet. Our insulin tolerance tests performed with the choice groups vs. control groups were not different. Our choice rats did not have altered glucose, insulin, or ITT, values compared with their controls.

In conclusion, pellet composition clearly affects sucrose and lard selection and the degree of obesity in rats offered the choice diet. Pellet type should be considered when determining the appropriate nutritional experimental control. The choice diet increased energy intake regardless of pellet type. LFD choice promoted hypertriglyceridemia and elevated liver lipids. With chow, liquid sucrose and lard promoted obesity. The choice model allows for a practical, alternative model of diet induced obesity.

Highlights.

Chow choice increased energy intake and body fat compared to chow fed control rats.

LFD choice rats did not increase carcass fat content compared to the LFD controls.

Rats consumed more lard when given the chow choice compared to the LFD choice diet.

The chow choice diet is a practical model of rapid onset diet-induced obesity.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a NIH RO1 DK53903 and Medical College of Georgia Diabetes and Obesity Discovery Institute Grant. The authors would like to thank Matt Hinnant for assisting with some animal and laboratory procedures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Young GS, Kirkland JB. Rat models of caloric intake and activity: relationships to animal physiology and human health. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism. 2007;32:161–176. doi: 10.1139/h06-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler AA, Kozak LP. A recurring problem with the analysis of energy expenditure in genetic models expressing lean and obese phenotypes. Diabetes. 2010;59:323–329. doi: 10.2337/db09-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munzberg H. Leptin-signaling pathways and leptin resistance. Forum Nutr. 2010;63:123–132. doi: 10.1159/000264400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers MG, Cowley MA, Munzberg H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annual review of physiology. 2008;70:537–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buettner R, Scholmerich J, Bollheimer LC. High-fat diets: modeling the metabolic disorders of human obesity in rodents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:798–808. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy ET, Bowman SA, Powell R. Dietary-fat intake in the US population. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999;18:207–212. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright J, Kennedy-Stephenson J, Wang C, McDowell M, Johnson C. Trends in Intake of Energy and Macronutrients --- United States, 1971--2000. Morbitity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beverage-World. Liquid Stats. Beverage World Publication Groups; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004;27:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattes RD. Dietary compensation by humans for supplemental energy provided as ethanol or carbohydrate in fluids. Physiol Behav. 1996;59:179–187. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas F, Ackroff K, Sclafani A. Dietary fat-induced hyperphagia in rats as a function of fat type and physical form. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:937–946. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sclafani A. Carbohydrate-induced hyperphagia and obesity in the rat: effects of saccharide type, form, and taste. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1987;11:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(87)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castonguay TW, Hirsch E, Collier G. Palatability of sugar solutions and dietary selection? Physiol Behav. 1981;27:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackroff K, Bonacchi K, Magee M, Yiin YM, Graves JV, Sclafani A. Obesity by choice revisited: effects of food availability, flavor variety and nutrient composition on energy intake. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.la Fleur SE, Luijendijk MCM, van Rozen AJ, Kalsbeek A, Adan RAH. A free-choice high-fat high-sugar diet induces glucose intolerance and insulin responsiveness to a glucose load not explained by obesity. International Journal of Obesity. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.164. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.la Fleur SE, van Rozen AJ, Luijendijk MC, Groeneweg F, Adan RA. A free-choice high-fat high-sugar diet induces changes in arcuate neuropeptide expression that support hyperphagia. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:537–546. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris RB. Factors influencing energy intake of rats fed either a high-fat or a fat mimetic diet. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994;18:632–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris RB. Growth measurements in Sprague-Dawley rats fed diets of very low fat concentration. J Nutr. 1991;121:1075–1080. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.7.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Balkan B, Keesey RE. Selective breeding for diet-induced obesity and resistance in Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R725–R730. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.2.R725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sclafani A, Xenakis S. Influence of diet form on the hyperphagia-promoting effect of polysaccharide in rats. Life sciences. 1984;34:1253–1259. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozul CD, Nomikos AP, Hampton TH, Warnke LA, Gosse JA, Davey JC, et al. Laboratory diet profoundly alters gene expression and confounds genomic analysis in mouse liver and lung. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;173:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tordoff MG, Pilchak DM, Williams JA, McDaniel AH, Bachmanov AA. The maintenance diets of C57BL/6J and 129X1/SvJ mice influence their taste solution preferences: implications for large-scale phenotyping projects. J Nutr. 2002;132:2288–2297. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reimer RA, Grover GJ, Koetzner L, Gahler RJ, Lyon MR, Wood S. The soluble fiber complex PolyGlycopleX lowers serum triglycerides and reduces hepatic steatosis in high-sucrose-fed rats. Nutr Res. 2011;31:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Artiss JD, Brogan K, Brucal M, Moghaddam M, Jen KL. The effects of a new soluble dietary fiber on weight gain and selected blood parameters in rats. Metabolism. 2006;55:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi YS, Cho SH, Kim HJ, Lee HJ. Effects of soluble dietary fibers on lipid metabolism and activities of intestinal disaccharidases in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1998;44:591–600. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.44.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lien EL, Boyle FG, Wrenn JM, Perry RW, Thompson CA, Borzelleca JF. Comparison of AIN-76A and AIN-93G diets: a 13-week study in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:385–392. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis SM, Ullrey DE, Barnard DE, Knapka JJ. Nutrition. In: Suckow MA, Weisbroth SH, Franklin CL, editors. The laboratory rat. 2nd ed. Burlington: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. p. 911. [Google Scholar]